Abstract

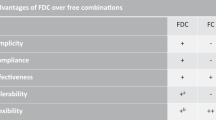

Ischemic heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death worldwide. A large proportion of individuals at high 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event live in low-income and middle-income countries, and the large majority of all cardiovascular events occur in developing countries. A large amount of evidence supports the use of pharmacological treatment for the prevention of cardiovascular death in this population, including antiplatelet drugs, beta blockers, lipid-lowering agents and angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. However, the efficacy of cardiovascular prevention is hampered by several problems, including inadequate prescription of medication, poor adherence to treatment, limited availability of medications and unaffordable cost of treatment. Here we examine the use of fixed-dose combination therapy (a 'polypill'), and how this therapy could improve adherence to treatment, reduce the cost and improve treatment affordability in low-income countries.

Key Points

-

In 2005, cardiovascular diseases caused 3.3 times more deaths worldwide than AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria combined

-

Of all cardiovascular events that occur worldwide, four-fifths occur in low-income and middle-income countries

-

Although the efficacy of medication for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease has been clearly demonstrated, a large proportion of potential candidates for therapy do not receive adequate treatment

-

Poor adherence to treatment and cost of medication are largely responsible for the discrepancy between evidence-based recommendations and actual treatment

-

Complexity of treatment is the main cause of patients' lack of adherence

-

Fixed-dose combination therapy (a 'polypill') might improve secondary prevention owing to a reduction in treatment complexity, and could provide medication at an affordable cost in developing countries

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fuster V and Voûte J (2005) MDGs: chronic diseases are not on the agenda. Lancet 366: 1512–1514

European Society of Cardiology and European Heart Network (online 2007) European Health Heart Charter [http://www.heartcharter.eu] (accessed 23 October 2008)

Rosamond W et al. (2008) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 117: e25–e146

Ezzati M et al. (2002) Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 360: 1347–1360

World Health Organization (online 2004) Priority Medicines for Europe and the World [http://archives.who.int/prioritymeds/Hague_Meeting/Nov24_Regulatory _approaches.ppt] (accessed 11 November 2008)

Fuster V et al. (2007) Low priority of cardiovascular and chronic diseases on the global health agenda: a cause for concern. Circulation 116: 1966–1970

The Center for Global Health and Economic Development (online 2004) A race against time: the challenge of cardiovascular disease in developing economies [http://www.ahpi.health.usyd.edu.au/pdfs/colloquia2004/leederracepaper.pdf] (accessed 12 November 2008)

Thom et al. (2006) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 113: e85–e151

Yusuf S et al. (2004) Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case–control study. Lancet 364: 937–952

Chiuve SE et al. (2006) Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men: benefits among users and nonusers of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation 114: 160–167

Ford ES et al. (2007) Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med 356: 2388–2398

Davies AR et al. (2007) Contribution of changes in incidence and mortality to trends in the prevalence of coronary heart disease in the UK: 1996–2005. Eur Heart J 28: 2142–2147

Kotseva K et al. (2001) Clinical reality of coronary prevention guidelines: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I and II in nine countries. Lancet 357: 995–1001

Kristensen SD et al. (2007) Highlights of the 2007 scientific sessions of the European Society of Cardiology Vienna, Austria, September 1–5, 2007. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 2421–2430

Granger CB et al. (2003) Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med 163: 2345–2353

Heras M et al. (2006) Reduction in acute myocardial infarction mortality over a five-year period [Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol 59: 200–208

Mendis S et al. (2005) WHO study on prevention of recurrences of myocardial infarction and stroke (WHO-PREMISE). Bull World Health Organ 83: 820–829

Fuster V and Sanz G (2007) A polypill for secondary prevention: time to move from intellectual debate to action. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 4: 173

Haynes RB et al. (1996) Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet 348: 383–386

Bosworth HB (2006) Medication treatment adherence. In Patient Treatment Adherence, 147–194 (Eds Bosworth et al.) New York: Routledge

PricewaterhouseCoopers (online 2008) Pharma 2020: The vision. Which path will you take? [http://www.pwc.com/Extweb/onlineforms.nsf/docid/ FF67E81D9B77C916852572F200628F3B?opendocument] (accessed 2 September 2008)

Mukherjee D et al. (2004) Impact of combination evidence-based medical therapy on mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 109: 745–749

Mukherjee D et al. (2002) Missed opportunities to treat atherosclerosis in patients undergoing peripheral vascular interventions: insights from the University of Michigan Peripheral Vascular Disease Quality Improvement Initiative (PVD-QI2). Circulation 106: 1909–1912

Danchin N et al. (2005) Impact of combined secondary prevention therapy after myocardial infarction: data from a nationwide French registry. Am Heart J 150: 1147–1153

Ho PM et al. (2006) Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 166: 1842–1847

Rasmussen JN et al. (2007) Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 297: 177–186

Lasker Foundation (online 2003) Facts about Heart Disease & Stroke [http://www.laskerfoundation.org/advocacy/pdf/factsheet2cardiovasc.pdf] (accessed 11 November 2008)

Franco OH et al. (2006) The polypill: at what price would it become cost effective? J Epidemiol Community Health 60: 213–217

Graziano TA et al. (2006) Cardiovascular disease prevention with a multidrug regimen in the developing world: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet 368: 679–686

Mendis S et al. (2007) The availability and affordability of selected essential medicines for chronic diseases in six low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 85: 279–288

Wald NJ and Law MR (2004) Formulation for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. UK patent GB2361186

Wald NJ and Law MR (2003) A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80%. BMJ 326: 1419

Sleight P et al. (2006) Benefits, challenges, and registerability of the polypill. Eur Heart J 27: 1651–1656

Wise J (2005) Polypill holds promise for people with chronic disease. Bull World Health Organ 83: 885–887

Combination Pharmacotherapy and Public Health Research Working Group (2005) Combination pharmacotherapy for cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med 143: 593–599

Dezii CM (2000) A retrospective study of persistence with single-pill combination therapy vs. concurrent two-pill therapy in patients with hypertension. Manag Care 9 (Suppl): 2–6

Taylor AA and Shoheiber O (2003) Adherence to antihypertensive therapy with fixed-dose amlodipine besylate/benazepril HCl versus comparable component-based therapy. Congest Heart Fail 9: 324–332

Bangalore S et al. (2007) Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 120: 713–719

Pan F et al. (2008) Impact of fixed-dose combination drugs on adherence to prescription medications. J Gen Intern Med 23: 611–614

Dickson M and Plauschinat CA (2008) Compliance with antihypertensive therapy in the elderly: a comparison of fixed-dose combination amlodipine/benazepril versus component-based free-combination therapy. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 8: 45–50

Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration (2002) Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 324: 71–86

Smith SC Jr et al. (2006) AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 113: 2363–2372.

Law MR et al. (2003) Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 326: 1423–1429

Baigent C et al. (2005) Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 366: 1267–1278

Lewington S et al. (2007) Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 370: 1829–1839

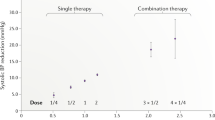

Law MR et al. (2003) Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ 326: 1427–1434.

Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration et al. (2008) Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 336: 1121–1123

Dagenais GR et al. (2006) Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in stable vascular disease without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure: a combined analysis of three trials. Lancet 368: 581–588

Danchin et al. (2006) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease and absence of heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction: an overview of long-term randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 166: 787–796

Yusuf S et al. (1985) Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 27: 335–371

Clinical Trials Research Unit, The University of Auckland (online 2008) PILL Pilot: Programme to Improve Life and Longevity [http://www.ctru.auckland.ac.nz/content/view/37/35/] (accessed 12 November 2008)

Wake Forest University School of Medicine (online 2008) Polypill for prevention of cardiovascular disease [http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00567307] (accessed 12 November 2008)

García Rodríguez LA et al. (2001) Association between aspirin and upper gastrointestinal complications: systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 52: 563–571

Dezii CM et al. (2002) Effects of once-daily and twice-daily dosing on adherence with prescribed glipizide oral therapy for type 2 diabetes. South Med J 95: 68–71

Acknowledgements

Ariana Del Negro, Medscape Cardiology, New York, NY and Désirée Lie, University of California, Irvine, CA, are the authors of and are solely responsible for the content of the learning objectives, questions and answers of the Medscape-accredited continuing medical education activity associated with this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanz, G., Fuster, V. Fixed-dose combination therapy and secondary cardiovascular prevention: rationale, selection of drugs and target population. Nat Rev Cardiol 6, 101–110 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1419

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1419

This article is cited by

-

Management verschiedener kardiovaskulärer Risikofaktoren mit einem Kombinationspräparat („Polypill“)

Herz (2018)

-

Polypille in der Sekundärprävention des Herzinfarktes

Der Kardiologe (2017)

-

Beyond Cholesterol in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Is The Polypill the Answer?

Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports (2011)

-

Should There Be a Different Cardiovascular Prevention Polypill Strategy for Women and Men?

Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports (2011)

-

Secondary prevention strategies for coronary heart disease

Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis (2010)