Abstract

Looking back at animal and clinical studies published since the 1920s, the notion of rapid regression and stabilization of atherosclerosis in humans has evolved from a fanciful goal to one that might be achievable pharmacologically, even for advanced plaques. Our review of this literature indicates that successful regression of atherosclerosis generally requires robust measures to improve plasma lipoprotein profiles. Examples of such measures include extensive lowering of plasma concentrations of atherogenic apolipoprotein B (apoB)-lipoproteins and enhancement of 'reverse' lipid transport from atheromata into the liver, either alone or in combination. Possible mechanisms responsible for lesion shrinkage include decreased retention of apoB-lipoproteins within the arterial wall, efflux of cholesterol and other toxic lipids from plaques, emigration of foam cells out of the arterial wall, and influx of healthy phagocytes that remove necrotic debris and other components of the plaque. Unfortunately, the clinical agents currently available cause less dramatic changes in plasma lipoprotein levels, and, thereby, fail to stop most cardiovascular events. Hence, there is a clear need for testing of new agents expected to facilitate atherosclerosis regression. Additional mechanistic insights will allow further progress.

Key Points

-

Regression (i.e. shrinkage and healing) of advanced, complex atherosclerotic plaques has been clearly documented in animals, and plausible evidence supports its occurrence in humans as well

-

The crucial event in atherosclerosis initiation is the retention, or trapping, of apolipoprotein-B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins within the arterial wall; this process leads to local responses to this retained material, including a maladaptive infiltrate of macrophages that consume the retained lipoproteins but then fail to emigrate

-

Plaque regression requires robust improvements in the plaque environment, specifically large reductions in plasma concentrations of apoB-lipoproteins and large increases in the 'reverse' transport of lipids out of the plaque for disposal

-

Regression is not merely a rewinding of progression, but instead involves emigration of the maladaptive macrophage infiltrate, followed by the initiation of a stream of healthy, normally functioning phagocytes that mobilize necrotic debris and all other components of advanced plaques

-

The challenge we face is making robust improvements in the plaque environment a widely achievable clinical goal. Additional strategies to provoke stabilization and regression of human atheromata, such as direct induction of CCR7 in plaque macrophages, might eventually become clinically feasible as well

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blankenhorn DH and Hodis HN (1994) George Lyman Duff Memorial Lecture: arterial imaging and atherosclerosis reversal. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 177–192

Stein Y and Stein O (2001) Does therapeutic intervention achieve slowing of progression or bona fide regression of atherosclerotic lesions? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 183–188

Stocker R and Keaney JF Jr (2004) Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev 84: 1381–1478

Ross R (1993) The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature 362: 801–809

Benditt EP and Benditt JM (1973) Evidence for a monoclonal origin of human atherosclerotic plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70: 1753–1756

Wissler RW and Vesselinovitch D (1976) Studies of regression of advanced atherosclerosis in experimental animals and man. Ann N Y Acad Sci 275: 363–378

Davies MJ et al. (1993) Risk of thrombosis in human atherosclerotic plaques: role of extracellular lipid, macrophage, and smooth muscle cell content. Br Heart J 69: 377–381

Friedman M et al. (1957) Resolution of aortic atherosclerotic infiltration in the rabbit by phosphatide infusion. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 95: 586–588

Williams KJ et al. (1984) Intravenously administered lecithin liposomes: a synthetic antiatherogenic lipid particle. Perspect Biol Med 27: 417–431

Armstrong ML (1976) Evidence of regression of atherosclerosis in primates and man. Postgrad Med J 52: 456–461

Malinow MR (1983) Experimental models of atherosclerosis regression. Atherosclerosis 48: 105–118

Maruffo CA and Portman OW (1968) Nutritional control of coronary artery atherosclerosis in the squirrel monkey. J Atheroscler Res 8: 237–247

Armstrong ML et al. (1970) Regression of coronary atheromatosis in rhesus monkeys. Circ Res 27: 59–67

Daoud AS et al. (1981) Sequential morphologic studies of regression of advanced atherosclerosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 105: 233–239

Williams KJ and Tabas I (2005) Lipoprotein retention—and clues for atheroma regression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1536–1540

Williams KJ and Scanu AM (1986) Uptake of endogenous cholesterol by a synthetic lipoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta 875: 183–194

Rodrigueza WV et al. (1997) Large versus small unilamellar vesicles mediate reverse cholesterol transport in vivo into two distinct hepatic metabolic pools: implications for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 2132–2139

Williams KJ et al. (2000) Rapid restoration of normal endothelial functions in genetically hyperlipidemic mice by a synthetic mediator of reverse lipid transport. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1033–1039

Rodrigueza WV et al. (1997) Remodeling and shuttling: mechanisms for the synergistic effects between different acceptor particles in the mobilization of cellular cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 383–393

Williams KJ et al. (1998) Structural and metabolic consequences of liposome–lipoprotein interactions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 32: 31–43

Rodrigueza WV et al. (1998) Cholesterol mobilization and regression of atheroma in cholesterol-fed rabbits induced by large unilamellar vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta 1368: 306–320

Rader DJ et al. (2002) Infusion of large unilamellar vesicles (ETC-588) mobilize unesterified cholesterol in a dose-dependent fashion in healthy volunteers [abstract]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: a-53

Williams KJ (1998) Method of forcing the reverse transport of cholesterol from a body part to the liver while avoiding harmful disruptions of hepatic cholesterol homeostasis. US Patent 5, 746, 223

Miyazaki A et al. (1995) Intravenous injection of rabbit apolipoprotein A-I inhibits the progression of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 1882–1888

Aikawa M and Libby P (2000) Lipid lowering reduces proteolytic and prothrombotic potential in rabbit atheroma. Ann NY Acad Sci 902: 140–152

Walsh A et al. (1989) High levels of human apolipoprotein A-I in transgenic mice result in increased plasma levels of small high density lipoprotein (HDL) particles comparable to human HDL3. J Biol Chem 264: 6488–6494

Plump AS et al. (1992) Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 71: 343–353

Ishibashi S et al. (1993) Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J Clin Invest 92: 883–893

Tangirala RK et al. (1999) Regression of atherosclerosis induced by liver-directed gene transfer of apolipoprotein A-I in mice. Circulation 100: 1816–1822

Shah PK et al. (2001) High-dose recombinant apolipoprotein A-I(milano) mobilizes tissue cholesterol and rapidly reduces plaque lipid and macrophage content in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice: potential implications for acute plaque stabilization. Circulation 103: 3047–3050

Rong JX et al. (2001) Elevating high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice remodels advanced atherosclerotic lesions by decreasing macrophage and increasing smooth muscle cell content. Circulation 104: 2447–2452

Wolfrum C et al. (2005) Apolipoprotein M is required for preβ-HDL formation and cholesterol efflux to HDL and protects against atherosclerosis. Nat Med 11: 418–422

Williams KJ et al. (1992) Mechanisms by which lipoprotein lipase alters cellular metabolism of lipoprotein(a), low density lipoprotein, and nascent lipoproteins: roles for low density lipoprotein receptors and heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem 267: 13284–13292

Ji ZS et al. (1993) Role of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the binding and uptake of apolipoprotein E-enriched remnant lipoproteins by cultured cells. J Biol Chem 268: 10160–10167

Williams KJ et al. (2005) Loss of heparan N-sulfotransferase in diabetic liver: role of angiotensin II. Diabetes 54: 1116–1122

Kashyap VS et al. (1995) Apolipoprotein E deficiency in mice: gene replacement and prevention of atherosclerosis using adenovirus vectors. J Clin Invest 96: 1612–1620

Tsukamoto K et al. (1997) Liver-directed gene transfer and prolonged expression of three major human ApoE isoforms in ApoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 100: 107–114

Tangirala RK et al. (2001) Reduction of isoprostanes and regression of advanced atherosclerosis by apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem 276: 261–266

Thorngate FE et al. (2000) Low levels of extrahepatic nonmacrophage ApoE inhibit atherosclerosis without correcting hypercholesterolemia in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1939–1945

Wientgen H et al. (2004) Subphysiologic apolipoprotein E (ApoE) plasma levels inhibit neointimal formation after arterial injury in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1460–1465

Harris JD et al. (2002) Acute regression of advanced and retardation of early aortic atheroma in immunocompetent apolipoprotein-E (apoE) deficient mice by administration of a second generation [E1(-), E3(-), polymerase(-)] adenovirus vector expressing human apoE. Hum Mol Genet 11: 43–58

Rosenfeld ME et al. (2000) Advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the innominate artery of the ApoE knockout mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 2587–2592

Reis ED et al. (2001) Dramatic remodeling of advanced atherosclerotic plaques of the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse in a novel transplantation model. J Vasc Surg 34: 541–547

Llodra J et al. (2004) Emigration of monocyte-derived cells from atherosclerotic lesions characterizes regressive, but not progressive, plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 11779–11784

Trogan E et al. (2006) Gene expression changes in foam cells and the role of chemokine receptor CCR7 during atherosclerosis regression in ApoE-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3781–3786

Trogan E et al. (2004) Serial studies of mouse atherosclerosis by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging detect lesion regression after correction of dyslipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1714–1719

Angeli V et al. (2004) Dyslipidemia associated with atherosclerotic disease systemically alters dendritic cell mobilization. Immunity 21: 561–574

Wallet MA et al. (2005) Immunoregulation of dendritic cells. Clin Med Res 3: 166–175

Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340: 115–126

Banchereau J and Steinman RM (1998) Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392: 245–252

Trogan E and Fisher EA (2005) Laser capture microdissection for analysis of macrophage gene expression from atherosclerotic lesions. Methods Mol Biol 293: 221–231

Forster R et al. (1999) CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99: 23–33

Chawla A et al. (2001) Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science 294: 1866–1870

Levin N et al. (2005) Macrophage liver X receptor is required for antiatherogenic activity of LXR agonists. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 135–142

Beaven SW and Tontonoz P (2006) Nuclear receptors in lipid metabolism: targeting the heart of dyslipidemia. Annu Rev Med 57: 313–329

Feig JE et al. (2006) CCR7 is functionally required for atherosclerosis regression and is activated by LXR [abstract]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: e-50

Lieu HD et al. (2003) Eliminating atherogenesis in mice by switching off hepatic lipoprotein secretion. Circulation 107: 1315–1321

Rong JX et al. (2004) Normalization of plasma total cholesterol in LDL receptor deficient (Ldlr−/−), apoB100 mice decreases the size and macrophage content of advanced atherosclerotic lesions [abstract]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: e-72

Raffai RL and Weisgraber KH (2002) Hypomorphic apolipoprotein E mice: a new model of conditional gene repair to examine apolipoprotein E-mediated metabolism. J Biol Chem 277: 11064–11068

Raffai RL et al. (2005) Apolipoprotein E promotes the regression of atherosclerosis independently of lowering plasma cholesterol levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 436–441

Ost CR and Stenson S (1967) Regression of peripheral atherosclerosis during therapy with high doses of nicotinic acid. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 99: 241–245

Brown BG et al. (1993) Lipid lowering and plaque regression: new insights into prevention of plaque disruption and clinical events in coronary disease. Circulation 87: 1781–1791

Farmer JA and Gotto AM Jr (2002) Dyslipidemia and the vulnerable plaque. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 44: 415–428

Stary HC et al. (1995) A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis: a report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 1512–1531

Brown BG et al. (2001) Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med 345: 1583–1592

Callister TQ et al. (1998) Effect of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on coronary artery disease as assessed by electron-beam computed tomography. N Engl J Med 339: 1972–1978

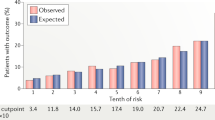

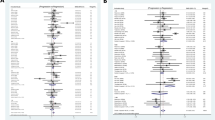

Nissen SE et al. (2004) Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291: 1071–1080

Nissen SE et al. (2006) Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA 295: 1556–1565

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (2001) Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285: 2486–2497

Wiviott SD et al. (2005) Can low-density lipoprotein be too low? The safety and efficacy of achieving very low low-density lipoprotein with intensive statin therapy: a PROVE IT-TIMI 22 substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 1411–1416

O'Leary DH and Polak JF (2002) Intima-media thickness: a tool for atherosclerosis imaging and event prediction. Am J Cardiol 90: 18L–21L

Taylor AJ et al. (2006) The effect of 24 months of combination statin and extended-release niacin on carotid intima-media thickness: ARBITER 3. Curr Med Res Opin 22: 2243–2250

Taylor AJ et al. (2004) Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol (ARBITER) 2: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of extended-release niacin on atherosclerosis progression in secondary prevention patients treated with statins. Circulation 110: 3512–3517

Nissen SE et al. (2003) Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290: 2292–2300

Tardif JC et al. (2007) Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297: 1675–1682

Barter PJ et al. (2007) Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med 357: 2109–2122

Nissen SE et al. (2007) Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 356: 1304–1316

Kastelein JJ et al. (2007) Effect of torcetrapib on carotid atherosclerosis in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 356: 1620–1630

Zhong S et al. (1996) Increased coronary heart disease in Japanese–American men with mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene despite increased HDL levels. J Clin Invest 97: 2917–2923

Curb JD et al. (2004) A prospective study of HDL-C and cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene mutations and the risk of coronary heart disease in the elderly. J Lipid Res 45: 948–953

Brousseau ME (2005) Emerging role of high-density lipoprotein in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Drug Discov Today 10: 1095–1101

Nicholls SJ et al. (2007) Statins, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and regression of coronary atherosclerosis. JAMA 297: 499–508

Williams KJ and Tabas I (1995) The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 551–561

Skålén K et al. (2002) Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature 417: 750–754

Pentikainen MO et al. (2002) Lipoprotein lipase in the arterial wall: linking LDL to the arterial extracellular matrix and much more. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 211–217

Gustafsson M et al. (2007) Retention of low-density lipoprotein in atherosclerotic lesions of the mouse: evidence for a role of lipoprotein lipase. Circ Res 101: 777–783

Watanabe N and Ikeda U (2004) Matrix metalloproteinases and atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 6: 112–120

Liu ML et al. (2007) Cholesterol enrichment of human monocyte/macrophages induces surface exposure of phosphatidylserine and the release of biologically-active tissue factor-positive microvesicles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 430–435

Field H Jr et al. (1960) Dynamic aspects of cholesterol metabolism in different areas of the aorta and other tissues in man and their relationship to atherosclerosis. Circulation 22: 547–558

Jagannathan SN et al. (1974) The turnover of cholesterol in human atherosclerotic arteries. J Clin Invest 54: 366–377

Guyton JR and Klemp KF (1996) Development of the lipid-rich core in human atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 16: 4–11

Sloop CH et al. (1987) Interstitial fluid lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 28: 225–237

Frias JC et al. (2006) Properties of a versatile nanoparticle platform contrast agent to image and characterize atherosclerotic plaques by magnetic resonance imaging. Nano Lett 6: 2220–2224

Bisoendial RJ et al. (2003) Restoration of endothelial function by increasing high-density lipoprotein in subjects with isolated low high-density lipoprotein. Circulation 107: 2944–2948

Kaul S et al. (2004) Rapid reversal of endothelial dysfunction in hypercholesterolemic apolipoprotein E-null mice by recombinant apolipoprotein A-I(Milano)-phospholipid complex. J Am Coll Cardiol 44: 1311–1319

Constantinides P (1981) Overview of studies on regression of atherosclerosis. Artery 9: 30–43

Pitt B (2005) Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with stable coronary heart disease—is it time to shift our goals? N Engl J Med 352: 1483–1484

Kastelein JJ et al. (2006) Potent reduction of apolipoprotein B and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by short-term administration of an antisense inhibitor of apolipoprotein B. Circulation 114: 1729–1735

Cuchel M et al. (2007) Inhibition of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 356: 148–156

Rader DJ (2007) Illuminating HDL—is it still a viable therapeutic target? N Engl J Med 357: 2180–2183

Zavoico GB (2003) Emerging Cardiovascular Therapeutics. Cambridge, MA, USA, June 10–11, 2003. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 21: 246–253

Acknowledgements

The original studies in the authors' laboratories were supported by NIH grants HL78667, HL61814, HL84312 (EAF), HL38956, HL56984, and HL73898 (KJW). Support is also acknowledged from the American Heart Association (KJW). JEF is a recipient of an NIH National Research Service Award F30 AG029748. Désirée Lie, University of California, Irvine, CA, is the author of and is solely responsible for the content of the learning objectives, questions and answers of the Medscape-accredited continuing medical education activity associated with this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

KJ Williams is the inventor of a number of US patents on the use of phospholipids to promote reverse lipid transport in mice (e.g. Williams KJ (1998) Method of forcing the reverse transport of cholesterol from a body part to the liver while avoiding harmful disruptions of hepatic cholesterol homeostasis. US Patent 5,746,223)

JE Feig and EA Fisher declared they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, K., Feig, J. & Fisher, E. Rapid regression of atherosclerosis: insights from the clinical and experimental literature. Nat Rev Cardiol 5, 91–102 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1086

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1086

This article is cited by

-

Clinical significance of microvessels detected by in vivo optical coherence tomography within human atherosclerotic coronary arterial intima: a study with multimodality intravascular imagings

Heart and Vessels (2021)

-

Glucose lowering by SGLT2-inhibitor empagliflozin accelerates atherosclerosis regression in hyperglycemic STZ-diabetic mice

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Role of AGEs in the progression and regression of atherosclerotic plaques

Glycoconjugate Journal (2018)

-

Inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease: a route to targeted therapies

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2017)

-

How radiation influences atherosclerotic plaque development: a biophysical approach in ApoE ¯/¯ mice

Radiation and Environmental Biophysics (2017)