Key Points

-

An increasing number of patients presenting with myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction rather than an MI with ST-segment elevation, and consequently survive their first event

-

The shift in the clinical presentation of acute coronary syndrome mandates a critical reassessment of the underlying mechanisms and the concept of the vulnerable plaque

-

This change in clinical presentation warrants re-assessment of currently applied cardiovascular risk scores, preclinical experiments, and the validity of population data collected before the application of current preventive interventions

Abstract

The concept of the 'vulnerable plaque' originated from pathological observations in patients who died from acute coronary syndrome. This recognition spawned a generation of research that led to greater understanding of how complicated atherosclerotic plaques form and precipitate thrombotic events. In current practice, an increasing number of patients who survive their first event present with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) rather than myocardial infarction (MI) with ST-segment elevation (STEMI). The culprit lesions that provide the pathological substrate for NSTEMI can vary considerably from the so-called 'vulnerable plaque'. The shift in clinical presentation of MI and stroke corresponds temporally to a progressive change in the characteristics of human plaques away from the supposed characteristics of vulnerability. These alterations in the structure and function of human atherosclerotic lesions might mirror the modifications that are produced in experimental plaques by lipid lowering, inspired by the vulnerable plaque construct. The shift in the clinical presentations of the acute coronary syndromes mandates a critical reassessment of the underlying mechanisms, proposed risk scores, the results and interpretation of preclinical experiments, as well as recognition of the limitations of the use of population data and samples collected before the application of current preventive interventions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: age-adjusted death rates* for heart disease and cancer,† by sex — United States, 1980–2011. CDC https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6337a6.htm (2014).

European Society of Cardiology. 2012 European cardiovascular disease statistics — visuals. escardio http://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/What-we-do/Initiatives/EuroHeart/2012-European-Cardiovascular-Disease-Statistics-Visuals (2012).

National Institutes of Health. Morbidity & mortality: 2012 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. NHLBI https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/research/2012_ChartBook_508.pdf (2012).

Yeh, R. W. et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 2155–2165 (2010).

Truven Health Analytics. Trends in acute myocardial infarction incidence, detection, and treatment. 100TopHospitals https://100tophospitals.com/Portals/2/assets/TOP_15192_1214_AMITrends_WEB.PDF (2015).

Khera, S. et al. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States: contemporary trends in incidence, utilization of the early invasive strategy, and in-hospital outcomes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, e000995 (2014).

Mannsverk, J. et al. Trends in modifiable risk factors are associated with declining incidence of hospitalized and nonhospitalized acute coronary heart disease in a population. Circulation 133, 74–81 (2016).

Plakht, Y., Gilutz, H. & Shiyovich, A. Temporal trends in acute myocardial infarction: what about survival of hospital survivors? Disparities between STEMI & NSTEMI remain. Soroka acute myocardial infarction II (SAMI-II) project. Int. J. Cardiol. 203, 1073–1081 (2016).

Moran, A. E. et al. The global burden of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010: the global burden of disease 2010 study. Circulation 129, 1493–1501 (2014).

Ford, E. S. & Capewell, S. Proportion of the decline in cardiovascular mortality disease due to prevention versus treatment: public health versus clinical care. Annu. Rev. Public Health 32, 5–22 (2011).

Franco, M. et al. Impact of energy intake, physical activity, and population-wide weight loss on cardiovascular disease and diabetes mortality in Cuba, 1980–2005. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166, 1374–1380 (2007).

Guasch-Ferré, M. et al. Dietary fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 102, 1563–1573 (2015).

US Food and Drug Administration. Sodium in your diet: use the nutrition facts label and reduce your intake. FDA http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm315393.htm (2016).

Bibbins-Domingo, K. et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 590–599 (2010).

Seo, D. C. & Torabi, M. R. Reduced admissions for acute myocardial infarction associated with a public smoking ban: matched controlled study. J. Drug Educ. 37, 217–226 (2007).

Juster, H. R. et al. Declines in hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction in New York state after implementation of a comprehensive smoking ban. Am. J. Public Health 97, 2035–2039 (2007).

Sargent, R. P., Shepard, R. M. & Glantz, S. A. Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study. BMJ 328, 977–980 (2004).

Schmucker, J. et al. Smoking ban in public areas is associated with a reduced incidence of hospital admissions due to ST-elevation myocardial infarctions in non-smokers. Results from the Bremen STEMI Registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21, 1180–1186 (2014).

Stone, N. J. et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 2889–2934 (2014).

Martin, S. S. et al. Clinician-patient risk discussion for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention: importance to implementation of the 2013 ACC/AHA Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 1361–1368 (2015).

Robinson, J. G. & Stone, N. J. The 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a new paradigm supported by more evidence. Eur. Heart J. 36, 2110–2118 (2015).

Ninomiya, T. et al. Blood pressure lowering and major cardiovascular events in people with and without chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 347, f5680 (2013).

Herrington, W., Lacey, B., Sherliker, P., Armitage, J. & Lewington, S. Epidemiology of atherosclerosis and the potential to reduce the global burden of atherothrombotic disease. Circ. Res. 118, 535–546 (2016).

Vandvik, P. O. et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 141, e637S–e668S (2012).

Udell, J. A. et al. Long-term dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in the subgroup of patients with previous myocardial infarction: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 37, 390–399 (2016).

Afzal, S., Tybjærg-Hansen, A., Jensen, G. B. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Change in body mass index associated with lowest mortality in Denmark, 1976–2013. JAMA 315, 1989–1996 (2016).

Mozaffarian, D. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2016 update. Circulation 133, e38–e360 (2016).

Sidney, S. et al. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 595–599 (2016).

Pearson-Stuttard, J. et al. Modelling future cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States: national trends and racial and ethnic disparities. Circulation 133, 967–978 (2016).

Keller, T. et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 9361, 868–877 (2009).

Reichlin, T. et al. Prospective validation of a 1-hour algorithm to rule-out and rule-in acute myocardial infarction using a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. CMAJ 187, E243–E252 (2015).

Shah, A. S. V. et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I at presentation in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet 386, 2481–2488 (2015).

Neumann, J. T. et al. Diagnosis of myocardial infarction using a high-sensitivity troponin I 1-hour algorithm. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 397–404 (2016).

Schofer, N. et al. Gender-specific diagnostic performance of a new high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay for detection of acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2048872615626660 (2016).

D'Souza, M. et al. Diagnosis of unstable angina pectoris has declined markedly with the advent of more sensitive troponin assays. Am. J. Med. 128, 852–860 (2015).

Rodriguez, F. & Mahaffey, K. W. Management of patients with NSTE-ACS: a comparison of the recent AHA/AAC and ESC guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 313–321 (2016).

Underhill, H. R. et al. Effect of rosuvastatin therapy on carotid plaque morphology and composition in moderately hypercholesterolemic patients: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging trial. Am. Heart J. 155, e1–e8 (2008).

Crisby, M. et al. Pravastatin treatment increases collagen content and decreases lipid content, inflammation, metalloproteinases, and cell death in human carotid plaques: implications for plaque stabilization. Circulation 103, 926–933 (2001).

Puri, R. et al. Long-term effects of maximally intensive statin therapy on changes in coronary atheroma composition: insights from SATURN. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 15, 380–388 (2014).

Libby, P. How does lipid lowering prevent coronary events? New insights from human imaging trials. Eur. Heart J. 36, 472–474 (2015).

Park, S. J. et al. Effect of statin treatment on modifying plaque composition: a double-blind, randomized Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 1772–1783 (2016).

Libby, P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 2004–2013 (2013).

Davies, M. J. & Thomas, A. Thrombosis and acute coronary-artery lesions in sudden cardiac ischemic death. N. Engl. J. Med. 310, 1137–1140 (1984).

van der Wal, A. C., Becker, A. E., van der Loos, C. M. & Das, P. K. Site of intimal rupture or erosion of thrombosed coronary atherosclerotic plaques is characterized by an inflammatory process irrespective of the dominant plaque morphology. Circulation 89, 36–44 (1994).

Falk, E. Plaque rupture with severe pre-existing stenosis precipitating coronary thrombosis. Characteristics of coronary atherosclerotic plaques underlying fatal occlusive thrombi. Br. Heart J. 50, 127–134 (1983).

Van Lammeren, G. W. et al. Time-dependent changes in atherosclerotic plaque composition in patients undergoing carotid surgery. Circulation 129, 2269–2276 (2014).

Virmani, R., Kolodgie, F. D., Burke, A. P., Farb, A. & Schwartz, S. M. Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 1262–1275 (2000).

Criqui, M. H. et al. Calcium density of coronary artery plaque and risk of incident cardiovascular events. JAMA 311, 271–278 (2014).

Puri, R. et al. Impact of statins on serial coronary calcification during atheroma progression and regression. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 1273–1282 (2015).

Smits, P. C. et al. Coronary artery disease: arterial remodelling and clinical presentation. Heart 82, 461–464 (1999).

Tian, J. et al. Significance of intraplaque neovascularisation for vulnerability: optical coherence tomography study. Heart 98, 1504–1509 (2012).

Farb, A. et al. Coronary plaque erosion without rupture into a lipid core. A frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in sudden coronary death. Circulation 93, 1354–1363 (1996).

Arbustini, E. et al. Plaque erosion is a major substrate for coronary thrombosis in acute myocardial infarction. Heart 82, 269–272 (1999).

Pasterkamp, G. et al. Inflammation of the atherosclerotic cap and shoulder of the plaque is a common and locally observed feature in unruptured plaques of femoral and coronary arteries. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 54–58 (1999).

Buffon, A. et al. Widespread coronary inflammation in unstable angina. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 5–12 (2002).

Stone, G. W. et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 226–235 (2011).

Arbab-Zadeh, A. & Fuster, V. The myth of the 'vulnerable plaque': transitioning from a focus on individual lesions to atherosclerotic disease burden for coronary artery disease risk assessment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 846–855 (2015).

Kelly, C. R. et al. Relation of C-reactive protein levels to instability of untreated vulnerable coronary plaques (from the PROSPECT study). Am. J. Cardiol. 114, 376–383 (2014).

Xie, Y. et al. Clinical outcome of nonculprit plaque ruptures in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the PROSPECT study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 7, 397–405 (2014).

Libby, P. & Theroux, P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation 111, 3481–3488 (2005).

Motoyama, S. et al. Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 337–346 (2015).

Ahmadi, A. et al. Do plaques rapidly progress prior to myocardial infarction? The interplay between plaque vulnerability and progression. Circ. Res. 117, 99–104 (2015).

Yokoya, K. et al. Process of progression of coronary artery lesions from mild or moderate stenosis to moderate or severe stenosis: a study based on four serial coronary arteriograms per year. Circulation 100, 903–909 (1999).

Takaya, N. et al. Presence of intraplaque hemorrhage stimulates progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation 111, 2768–2775 (2005).

Hellings, W. E. et al. Composition of carotid atherosclerotic plaque is associated with cardiovascular outcome: a prognostic study. Circulation 121, 1941–1950 (2010).

Koton, S. et al. Stroke incidence and mortality trends in US communities, 1987 to 2011. JAMA 312, 259–268 (2014).

Vaartjes, I., O'Flaherty, M., Capewell, S., Kappelle, J. & Bots, M. Remarkable decline in ischemic stroke mortality is not matched by changes in incidence. Stroke 44, 591–597 (2013).

Lackland, D. T. et al. Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45, 315–353 (2014).

Verhoeven, B. A. N. et al. Athero-express: Differential atherosclerotic plaque expression of mRNA and protein in relation to cardiovascular events and patient characteristics. Rationale and design. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19, 1127–1133 (2004).

Rozanski, A. et al. Temporal trends in the frequency of inducible myocardial ischemia during cardiac stress testing: 1991 to 2009. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 1054–1065 (2013).

Durand, E. et al. In vivo induction of endothelial apoptosis leads to vessel thrombosis and endothelial denudation: a clue to the understanding of the mechanisms of thrombotic plaque erosion. Circulation 109, 2503–2506 (2004).

Saia, F. et al. Eroded versus ruptured plaques at the culprit site of STEMI: in vivo pathophysiological features and response to primary PCI. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 8, 566–575 (2015).

Heikkila, H. M. et al. Activated mast cells induce endothelial cell apoptosis by a combined action of chymase and tumor necrosis factor-α. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 309–314 (2008).

Mäyränpää, M. I., Heikkilä, H. M., Lindstedt, K. A, Walls, A. F. & Kovanen, P. T. Desquamation of human coronary artery endothelium by human mast cell proteases: implications for plaque erosion. Coron. Artery Dis. 17, 611–621 (2006).

Dimmeler, S. & Zeiher, A. M. Reactive oxygen species and vascular cell apoptosis in response to angiotensin II and pro-atherosclerotic factors. Regul. Pept. 90, 19–25 (2000).

Quillard, T. et al. TLR2 and neutrophils potentiate endothelial stress, apoptosis and detachment: implications for superficial erosion. Eur. Heart J. 36, 1394–1404 (2015).

Ferrante, G. et al. High levels of systemic myeloperoxidase are associated with coronary plaque erosion in patients with acute coronary syndromes: an in vivo optical coherence tomography study. Eur. Heart J. 31, 451–452 (2010).

Liaw, P. C., Ito, T., Iba, T., Thachil, J. & Zeerleder, S. DAMP and DIC: the role of extracellular DNA and DNA-binding proteins in the pathogenesis of DIC. Blood Rev. 30, 257–261 (2015).

Koenig, W. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and atherosclerotic disease: from improved risk prediction to risk-guided therapy. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 5126–5134 (2013).

Duivenvoorden, R., de Groot, E., Stroes, E. S. G. & Kastelein, J. J. P. Surrogate markers in clinical trials — challenges and opportunities. Atherosclerosis 206, 8–16 (2009).

Libby, P. & King, K. Biomarkers: a challenging conundrum in cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 2491–2495 (2015).

Brennan, M.-L. et al. Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1595–1604 (2003).

Ridker, P. M., Hennekens, C. H., Buring, J. E. & Rifai, N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 836–843 (2000).

Rodriguez-Granillo, G. A. et al. In vivo intravascular ultrasound-derived thin-cap fibroatheroma detection using ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46, 2038–2042 (2005).

Romer, T. et al. Histopathology of human coronary atherosclerosis by quantifying its chemical composition with Raman spectroscopy. Circulation 97, 878–885 (1998).

Casscells, W. et al. Thermal detection of cellular infiltrates in living atherosclerotic plaques: possible implications for plaque rupture and thrombosis. Lancet 347, 1447–1449 (1996).

Brugaletta, S. et al. NIRS and IVUS for characterization of atherosclerosis in patients undergoing coronary angiography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 4, 647–655 (2011).

Fujimoto, J. G. et al. High resolution in vivo intra-arterial imaging with optical coherence tomography. Heart 82, 128–133 (1999).

Jang, I.-K. et al. Visualization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in patients using optical coherence tomography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 39, 604–609 (2002).

Simpson, R. J. et al. MR imaging-detected carotid plaque hemorrhage is stable for 2 years and a marker for stenosis progression. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 1171–1175 (2015).

Smilde, T. J. et al. Effect of aggressive versus conventional lipid lowering on atherosclerosis progression in familial hypercholesterolaemia (ASAP): a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 357, 577–581 (2001).

Kastelein, J. J. P. et al. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1431–1443 (2008).

Bittencourt, M. S. et al. Prognostic value of nonobstructive and obstructive coronary artery disease detected by coronary computed tomography angiography to identify cardiovascular events. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 7, 282–291 (2014).

Wang, T. J. et al. Prognostic utility of novel biomarkers of cardiovascular stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 126, 1596–1604 (2012).

Ridker, P. M. & Cook, N. R. Statins: new American guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Lancet 382, 1762–1765 (2013).

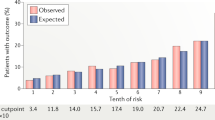

DeFilippis, A. P. et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, 266–275 (2015).

Goff, D. C. et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 2935–2959 (2014).

Cook, N. R. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation 115, 928–935 (2007).

Rana, J. S. et al. Accuracy of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk equation in a large contemporary, multiethnic population. 67, 2118–2130 (2016).

Blaha, M. J. The critical importance of risk score calibration: time for transformative approach to risk score validation? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 2131–2134 (2016).

Ishibashi, S. et al. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 883–893 (1993).

Plump, A. S. et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 71, 343–353 (1992).

Williams, H., Johnson, J. L., Carson, K. G. S. & Jackson, C. L. Characteristics of intact and ruptured atherosclerotic plaques in brachiocephalic arteries of apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 788–792 (2002).

Libby, P. Murine 'model' monotheism: an iconoclast at the altar of mouse. Circ. Res. 117, 921–925 (2015).

Pasterkamp, G. et al. Human validation of genes associated with a murine atherosclerotic phenotype. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 36, 1240–1246 (2016).

Shiomi, M. et al. Vasospasm of atherosclerotic coronary arteries precipitates acute ischemic myocardial damage in myocardial infarction-prone strain of the watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 2518–2523 (2013).

Burke, A. P. et al. Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 1276–1282 (1997).

Dai, J. et al. Association between cholesterol crystals and culprit lesion vulnerability in patients with acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study. Atherosclerosis 247, 111–117 (2016).

Ino, Y. et al. Difference of culprit lesion morphologies between ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 4, 76–82 (2011).

Niccoli, G. et al. Plaque rupture and intact fibrous cap assessed by optical coherence tomography portend different outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 36, 1377–1384 (2015).

Refaat, H. et al. Optical coherence tomography features of angiographic complex and smooth lesions in acute coronary syndromes. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 31, 927–934 (2015).

Jia, H. et al. In vivo diagnosis of plaque erosion and calcified nodule in patients with acute coronary syndrome by intravascular optical coherence tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 1748–1758 (2013).

Ong, D. S. et al. Coronary calcification and plaque vulnerability: an optical coherence tomographic study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 9, e003929 (2016).

Vergallo, R. et al. Pancoronary plaque vulnerability in patients with acute coronary syndrome and ruptured culprit plaque: a 3-vessel optical coherence tomography study. Am. Heart J. 167, 59–67 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Variable underlying morphology of culprit plaques associated with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an optical coherence tomography analysis from the SMART trial. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 16, 1381–1389 (2015).

Lee, C. W. et al. Differences in intravascular ultrasound and histological findings in culprit coronary plaques between ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and stable angina. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 37, 443–449 (2014).

Bogale, N. et al. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) evaluation of intermediate coronary lesions in patients with NSTEMI. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 17, 113–118 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P. and P.L. researched data for the article. All authors contributed substantially to discussion of content, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pasterkamp, G., den Ruijter, H. & Libby, P. Temporal shifts in clinical presentation and underlying mechanisms of atherosclerotic disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 14, 21–29 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.166

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.166

This article is cited by

-

A novel deep learning model for a computed tomography diagnosis of coronary plaque erosion

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Does Coronary Plaque Morphology Matter Beyond Plaque Burden?

Current Atherosclerosis Reports (2023)

-

Residual risks and evolving atherosclerotic plaques

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2023)

-

PET/MR imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis

Nature Biomedical Engineering (2022)

-

Considerations on PET/MR imaging of carotid plaque inflammation with 68Ga-Pentixafor

Journal of Nuclear Cardiology (2022)