Abstract

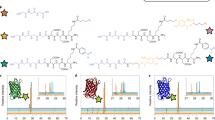

Wnt signaling is crucial during embryonic development and for the maintenance of adult tissues. Depending on the tissue type, the Wnt pathway can promote stem cell self-renewal and/or direct lineage commitment. Wnt proteins are subject to lipid modification, often restricting them to act in a localized manner on responsive cells. Most methods for inducing Wnt signaling in stem cell cultures do not control the spatial presentation of the protein. To recreate the local presentation of Wnt proteins often seen in vivo, we previously developed a method to immobilize the protein onto synthetic surfaces. Here we describe a detailed protocol based on covalent binding of nucleophilic groups on Wnt proteins to activated carboxylic acid (COOH) or glutaraldehyde (COH) groups functionalized on synthetic surfaces. As an example, we describe how this method can be used to covalently immobilize Wnt3a proteins on microbeads or a glass surface. This procedure requires ∼3 h and allows for the hydrophobic protein to be stored in the absence of detergent. The immobilization efficiency of active Wnt proteins can be assessed using different T-cell factor (TCF) reporter assays as a readout for Wnt/β-catenin-dependent transcription. Immobilization efficiency can be measured 12–18 h after seeding the cells and takes 2–4 h. The covalent immobilization of Wnt proteins can also be used for single-cell analysis using Wnt-coated microbeads (12–18 h of live imaging) and to create a Wnt platform on a glass surface for stem cell maintenance and cell population analysis (3 d). The simple chemistry used for Wnt immobilization allows for adaptation to new materials and other developmental signals. Therefore, this method can also be incorporated into tissue engineering platforms in which depletion of the stem cell pool restricts the complexity and maturity of the tissue developed.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jones, D.L. & Wagers, A.J. No place like home: anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 11–21 (2008).

Losick, V.P., Morris, L.X., Fox, D.T. & Spradling, A. Drosophila stem cell niches: a decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev. Cell 21, 159–171 (2011).

Clevers, H., Loh, K.M. & Nusse, R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science 346, 1248012 (2014).

Takada, R. et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid modification of Wnt protein: its role in Wnt secretion. Dev. Cell 11, 791–801 (2006).

Willert, K. et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature 423, 448–452 (2003).

Alexandre, C., Baena-Lopez, A. & Vincent, J.-P. Patterning and growth control by membrane-tethered Wingless. Nature 505, 180–185 (2013).

Farin, H.F. et al. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature 530, 340–343 (2016).

Goldstein, B., Takeshita, H., Mizumoto, K. & Sawa, H. Wnt signals can function as positional cues in establishing cell polarity. Dev. Cell 10, 391–396 (2006).

van den Heuvel, M., Nusse, R., Johnston, P. & Lawrence, P.A. Distribution of the wingless gene product in Drosophila embryos: a protein involved in cell-cell communication. Cell 59, 739–749 (1989).

Langton, P.F., Kakugawa, S. & Vincent, J.-P. Making, exporting, and modulating Wnts. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 756–765 (2016).

Janda, C.Y., Waghray, D., Levin, A.M., Thomas, C. & Garcia, K.C. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science 337, 59–64 (2012).

Chu, M.L.-H. et al. Structural studies of Wnts and identification of an LRP6 binding site. Structure 21, 1235–1242 (2013).

MacDonald, B.T. et al. Disulfide bond requirements for active Wnt ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18122–18136 (2014).

Bazan, J.F., Janda, C.Y. & Garcia, K.C. Structural architecture and functional evolution of Wnts. Dev. Cell 23, 227–232 (2012).

ten Berge, D. et al. Embryonic stem cells require Wnt proteins to prevent differentiation to epiblast stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1070–1075 (2011).

Reya, T. et al. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423, 409–414 (2003).

Huang, J., Nguyen-McCarty, M., Hexner, E.O., Danet-Desnoyers, G. & Klein, P.S. Maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells through regulation of Wnt and mTOR pathways. Nat. Med. 18, 1778–1785 (2012).

Zeng, Y.A. & Nusse, R. Wnt proteins are self-renewal factors for mammary stem cells and promote their long-term expansion in culture. Cell Stem Cell 6, 568–577 (2010).

Kalani, M.Y.S. et al. Wnt-mediated self-renewal of neural stem/progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16970–16975 (2008).

Yin, X. et al. Niche-independent high-purity cultures of Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells and their progeny. Nat. Methods 11, 106–112 (2014).

Reya, T. & Clevers, H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature 434, 843–850 (2005).

Habib, S.J. et al. A localized Wnt signal orients asymmetric stem cell division in vitro. Science 339, 1445–1448 (2013).

Morrison, S.J. & Kimble, J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature 441, 1068–1074 (2006).

Lowndes, M., Rotherham, M., Price, J.C., El Haj, A.J. & Habib, S.J. Immobilized WNT proteins act as a stem cell niche for tissue engineering. Stem Cell Rep. 7, 126–137 (2016).

Klaus, A. & Birchmeier, W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 387–398 (2008).

Panáková, D., Sprong, H., Marois, E., Thiele, C. & Eaton, S. Lipoprotein particles are required for Hedgehog and Wingless signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 435, 58–65 (2005).

Morrell, N.T. et al. Liposomal packaging generates Wnt protein with in vivo biological activity. PLoS One 3, e2930 (2008).

Zhao, L. et al. Controlling the in vivo activity of Wnt liposomes. Methods Enzymol. 465, 331–347 (2009).

Lalefar, N.R., Witkowski, A., Simonsen, J.B. & Ryan, R.O. Wnt3a nanodisks promote ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 14, 66 (2016).

ten Berge, D., Brugmann, S.A., Helms, J.A. & Nusse, R. Wnt and FGF signals interact to coordinate growth with cell fate specification during limb development. Development 135, 3247–3257 (2008).

Ying, Q.-L. et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature 453, 519–523 (2008).

Myers, C.T., Appleby, S.C. & Krieg, P.A. Use of small molecule inhibitors of the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways during Xenopus development. Methods 66, 380–389 (2014).

Hoffman, M.D. & Benoit, D.S.W. Agonism of Wnt-β-catenin signalling promotes mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) expansion. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 9, E13–E26 (2015).

Kirkeby, A. et al. Generation of regionally specified neural progenitors and functional neurons from human embryonic stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Rep. 1, 703–714 (2012).

Rotherham, M. & El Haj, A.J. Remote activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway using functionalised magnetic particles. PLoS One 10, e0121761 (2015).

Niehrs, C. The complex world of WNT receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 767–779 (2012).

van Amerongen, R. & Nusse, R. Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development 136, 3205–3214 (2009).

O'Brien, F.J. Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 14, 88–95 (2011).

Doyle, A.D. Generation of micropatterned substrates using micro photopatterning. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 10, Unit 10.15 (2009).

Nusse, R. Wnts and Hedgehogs: lipid-modified proteins and similarities in signaling mechanisms at the cell surface. Development 130, 5297–5305 (2003).

Fuerer, C., Habib, S.J. & Nusse, R. A study on the interactions between heparan sulfate proteoglycans and Wnt proteins. Dev. Dyn. 239, 184–190 (2010).

Fuerer, C. & Nusse, R. Lentiviral vectors to probe and manipulate the Wnt signaling pathway. PLoS One 5, e9370 (2010).

Migneault, I., Dartiguenave, C., Bertrand, M.J. & Waldron, K.C. Glutaraldehyde: behavior in aqueous solution, reaction with proteins, and application to enzyme crosslinking. Biotechniques 37 790–796, 798–802 (2004).

Mihara, E. et al. Active and water-soluble form of lipidated Wnt protein is maintained by a serum glycoprotein afamin/α-albumin. Elife 5, e11621 (2016).

Blitzer, J.T. & Nusse, R. A critical role for endocytosis in Wnt signaling. BMC Cell Biol. 7, 28 (2006).

Mikels, A.J. & Nusse, R. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 4, e115 (2006).

Nagy, A., Rossant, J., Nagy, R., Abramow-Newerly, W. & Roder, J.C. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 8424–8428 (1993).

Auerbach, W. et al. Establishment and chimera analysis of 129/SvEv- and C57BL/6-derived mouse embryonic stem cell lines. Biotechniques 29, 1024–1032 (2000).

Frigault, M.M., Lacoste, J., Swift, J.L. & Brown, C.M. Live-cell microscopy - tips and tools. J. Cell Sci. 122, 753–767 (2009).

Nolan, T., Hands, R.E. & Bustin, S.A. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1559–1582 (2006).

Jho, E.-H. et al. Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1172–1183 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Chiappini, C. Garcin and E. Rognoni for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship (102513/Z/13/Z to S.J.H.) and a grant from the UK Regenerative Medicine Platform (MRC Niche Hub Reference MR/K026666/1 to S.J.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., S.J. and S.J.H. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.J.H. is named on pending US patent application no. 20140171356 A1 (Chemically immobilized Wnt protein and methods of use).

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Flow cytometry gating strategy.

Individual histograms from Figure 3. On the right of each histogram is the gating strategy, showing the subpopulation percentages. The gate for the FSC-A × SSC-A plots was used to determine the cell population from all events. The gate on the FSC-A × Comp-Pacific-Blue-A plots separates the live from the dead cells, which have incorporated the DAPI stain. A chart shows the final number of cells analyzed, along with the statistics for each condition (geometric mean and coefficient of variation).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1

Flow cytometry gating strategy. Individual histograms from Figure 3. On the right of each histogram is the gating strategy, showing the subpopulation percentages. The gate for the FSC-A × SSC-A plots was used to determine the cell population from all events. The gate on the FSC-A × Comp-Pacific-Blue-A plots separates the live from the dead cells, which have incorporated the DAPI stain. A chart shows the final number of cells analyzed, along with the statistics for each condition (geometric mean and coefficient of variation). (PDF 260 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lowndes, M., Junyent, S. & Habib, S. Constructing cellular niche properties by localized presentation of Wnt proteins on synthetic surfaces. Nat Protoc 12, 1498–1512 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2017.061

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2017.061

This article is cited by

-

Wnt-modified materials mediate asymmetric stem cell division to direct human osteogenic tissue formation for bone repair

Nature Materials (2021)

-

Hepatocyte organoids and cell transplantation: What the future holds

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2021)

-

Joint single-cell multiomic analysis in Wnt3a induced asymmetric stem cell division

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.