Abstract

Euphoric and mixed (dysphoric) manic symptoms have different response patterns to divalproex and lithium in acute mania treatment, but have not been studied in relationship to maintenance treatment outcomes. We examined the impact of initial euphoric or dysphoric manic symptomatology on maintenance outcome. Randomized maintenance treatment with divalproex, lithium, or placebo was provided for 372 bipolar I patients, who met improvement criteria during open phase treatment for an index manic episode. The current analysis grouped patients according to the index manic episode subtype (euphoric or dysphoric), and evaluated the impact on maintenance treatment outcome. The rate of early discontinuation due to intolerance during maintenance treatment was higher for initially dysphoric patients (N=249) than euphoric patients (N=123; 15.7 vs 7.3%, respectively; p=0.032). Both lithium (23.2%) and divalproex (17.1%) were associated with more premature discontinuations due to intolerance than placebo (4.8%; p=0.003 and 0.02, respectively) in the initially dysphoric patients. Among initially euphoric patients, treatment with lithium was associated with significantly more premature discontinuations due to intolerance compared to placebo (18.2 vs 0%; p=0.03), and divalproex was significantly (p=0.05) more effective than lithium, but not placebo in delaying time to a depressive episode. Initial euphoric mania appeared to predispose to better outcomes on indices of depression and overall function with divalproex maintenance than with either placebo or lithium. Dysphoric mania appeared to predispose patients to more side effects when treated with either divalproex or lithium during maintenance therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Recent randomized, placebo-controlled trials in patients with bipolar I disorder have demonstrated the significant but limited prophylactic efficacy of lithium, divalproex, lamotrigine and olanzapine (Bowden et al, 2000, 2003a, 2003b; Calabrese et al, 2003; Tohen et al, 2003). However, little data exist to aid psychiatrists in selecting the treatment most likely to be well tolerated and efficacious during maintenance therapy for a given patient.

Most treatment guidelines recommend that if a drug proves effective initially it be continued as the maintenance treatment, unless side effects preclude long-term use of the agent. Several studies indicate that patients with dysphoric, or mixed mania have relatively poor acute responses to lithium, and are significantly more likely to respond to divalproex (Keller et al, 1986; Keller 1988; Secunda et al, 1985, 1987; Himmelhoch and Garfinkel, 1986; Freeman et al, 1992; Swann et al, 1999). Several reports suggest that mixed manic patients have generally worse illness courses than euphoric (pure) manic patients (Turvey et al, 1999; Keller, 1988). No study has addressed whether pure or mixed manic symptomatology initially is associated with differential treatment effectiveness of mood stabilizers during maintenance therapy. This study examines in further detail the maintenance efficacy and tolerability of divalproex and lithium in relationship to euphoric or dysphoric manic symptomatology during the acute episode antecedent to blinded, randomized treatment with divalproex, lithium, or placebo for 1 year.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Methodology for this study has been previously described in detail (Bowden et al, 2000). This report describes additional analyses of a trial that randomized 372 bipolar I patients to maintenance treatment with divalproex, lithium, or placebo, after having recovered from an index manic episode within 3 months of onset (Bowden et al, 2000). Eligible patients were between the ages of 18 and 75 years old with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, type I; a history of rapid cycling was not exclusionary. The index manic episode was diagnosed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID; Spitzer et al, 1990; American Psychiatric Association, 1987), which does not provide a diagnosis of mixed mania. The initial open phase lasted 3 months or less, followed by a 52-week, randomized maintenance phase. During the open phase, the index manic episode was treated at the discretion of the investigator, including treatment with divalproex, lithium, both agents, other drugs, or no mood stabilizer. Thus, the criteria for randomization could be met with or without drug treatment during the open phase. Psychotropic medications other than divalproex or lithium were discontinued before randomization. At the end of the open phase, eligible patients were randomized in a 2 : 1 : 1 ratio to divalproex (n=187), lithium (n=91), or placebo (n=94).

Patients were classified as having euphoric or dysphoric mania during the index episode at the time of the highest scored Mania Rating Scale (MRS). The highest score was from the initial assessment in nearly all patients. The criteria for dysphoric mania were defined as the presence of the depressive mood item from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) Depressive Syndrome subscale (DSS), and at least one additional DSS item: worry, self-reproach, negative evaluation of self, discouragement, suicidal tendency, feeling of fatigue, loss of interest, or social withdrawal (Swann et al, 1997). Each of the nine DSS items was scored from 0 (absent) to 5; a score of 1 or more indicates that the symptom was present. Patients not meeting the criteria for dysphoric mania were categorized as euphoric (pure) mania.

Study visits were conducted weekly or every other week for the first 12 weeks of the maintenance phase, and then monthly. Patients could only be taking divalproex or lithium, but not both, on the day prior to randomization. Open-label divalproex or lithium was slowly withdrawn during the first 2 weeks of the maintenance phase, with concomitant upward dosage titration of the blinded study medication. Restricted use of rescue medications was allowed in order to minimize the recurrence of manic symptoms caused by withdrawal of open-label medication. Concomitant lorazepam (up to 6 mg/day) was permitted for a 14-day maximum period during the first month, and for no more than 7 days for the remainder of the study. Concomitant haloperidol (⩽10 mg/day) was permitted during the second consecutive week of lorazepam use in the first month only. Neither lorazepam nor haloperidol was allowed within 8 h before behavioral assessments.

Efficacy outcome measures that were established a priori included: time to a mood episode (any, mania, or depression), time in maintenance period, premature discontinuation rates, and mean change from baseline in scores on the MRS, DSS, and Global Assessment Scale (GAS), all derived from the SADS-Change Version. An additional outcome measure: time to a mood episode or premature discontinuation was a post hoc determined outcome measure designed as an indication of effectiveness, combining both elements of efficacy and tolerability of a treatment.

A manic episode was defined as an MRS score of at least 16 or requiring hospitalization. A depressive episode was defined as requiring antidepressant use or premature discontinuation from the study because of symptoms. Subjects with DSS scores ⩾25 were treated with sertraline or paroxetine, and their data were censored from the analysis of time to mania relapse on the day that antidepressant treatment began.

All tests were two-tailed. Analyses were performed with the SAS System, Version 6 (SAS Institute, 1989). p-values ⩽0.050 were considered statistically significant. Comparability of groups at baseline was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, by the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for ordered categorical variables, and by Fisher's exact test for qualitative variables. Differences in rates of premature discontinuation overall and for intolerance were assessed by Fisher's exact test. Survival analyses of time to any mood episode, time to depression, time to mania, and time to any mood episode to premature discontinuation (whichever came first) were performed for the intent-to-treat sample (all subjects receiving at least one dose of study drug). Life-table methods were employed to compare survival curves, and group differences were assessed by the log-rank test. Differences in time in study were assessed by one-way ANOVA. Differences in baseline and mean change from baseline to the average score for MRS and DSS scores from the SADS-C and for GAS scores were assessed both by a two-way ANOVA with factors for treatment, mania subtype, and treatment by mania subtype interaction, as well as by one-way ANOVA with either treatment or mania subtype as the factor.

RESULTS

Patients and Study Dosing

Demographic characteristics were generally comparable between the initially euphoric and dysphoric patient groups (Table 1) with the exception of time since last depressive episode and baseline DSS scores. Patients classified as initially dysphoric had a prior depressive episode that was significantly more recent than the patients classified as initially euphoric (434 vs 806 days; p<0.001), and also had a significantly higher baseline mean DSS score (5.7 vs 3.5, respectively; p<0.001; Table 1). Multiple psychiatric history variables were combined to calculate an index of illness burden including, whether ever hospitalized, age of onset of first mania episode, age of onset of first depressive episode, number of prior manic and prior depressive episodes, and number of days since most recent depressive episode. This assessment demonstrated significantly greater disease burden in the dysphoric mania patients compared to the euphoric mania patients (Mantel–Haenszel χ2, p=0.013), which was primarily due to earlier age at first manic episode, earlier age at first depressive episode, and a more recent depressive episode.

There were no differences in the open medication received as a function of the type of mania (initially dysphoric or euphoric). Of the 247 patients classified as initially dysphoric, 89 (36%) were treated in the index phase with lithium, 104 (42%) with divalproex, and 54 (22%) with no mood stabilizer. Of the 122 patients classified as initially euphoric, 53 (43%) were treated in the index phase with lithium, 44 (36%) with divalproex, and 25 (20%) with no mood stabilizer. Likewise, there was no relationship between the open medication received and the randomized medication for either of the two mania subtypes. During the index episode, 49 patients were treated with both divalproex and lithium, of which 18 were euphoric and 31 were dysphoric. Of the 49, 32 were treated with divalproex closest to randomization, and 17 with lithium. Roughly equal numbers of each mania subtype were included in each of these open phase treatment groups.

The study drug was administered three times daily and the dose gradually increased based on body weight to target serum trough concentrations of 71–125 μg/ml for valproate and 0.8–1.2 mEq/l for lithium. By day 30 of randomized treatment, the mean (±SD) serum concentrations were 84.8±29.9 μg/ml for valproate and 1.0±0.48 mEq/l for lithium; concentrations remained stable in subsequent months. Day 30 serum concentrations were similar for the initially euphoric and dysphoric patient subgroups. The mean lithium serum concentrations were 1.0±0.47 mEq/l for the initially euphoric subjects, and 1.0±0.49 mEq/l for the initially dysphoric subjects. The mean valproate serum concentrations were 85.8±30.44 μg/ml for the initially euphoric subjects, and 84.2±29.7 μg/ml for the initially dysphoric subjects.

Premature Discontinuations

For the entire sample, there was no significant difference (p=0.154) in premature discontinuation rates between the initially euphoric (63.4%) and initially dysphoric (71.1%) patients during the maintenance phase. Among initially euphoric patients, there were nonsignificant trends toward lower rates of premature discontinuation during the maintenance phase when treated with divalproex than with lithium (54.3 vs 77.3%; p=0.08) or placebo (74.2%; p=0.08; Table 2). There was no differential treatment effect on premature discontinuation rates within the initially dysphoric patients.

Efficacy

Time to mania or depression

For the full sample, there was no significant difference between the initially euphoric or dysphoric patients in the time to any mood episode. Similarly, there were no differences by treatment group in time to any mood episode for either dysphoric or euphoric patients.

Time to depression

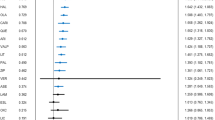

For the full sample, there was no significant difference between the initially euphoric or dysphoric patients in the time to a depressive episode. Among initially euphoric patients, divalproex was significantly (p=0.05) more effective than lithium in delaying time to a depressive episode, and tended to be superior to placebo (p=0.11; Figure 1a). There were no significant treatment-related differences in the dysphoric patients on time to a depressive episode (Figure 1b).

Time to mania

For the full sample, there was no significant difference between the initially euphoric or dysphoric patients in the time to a manic episode. There were no significant treatment-related differences in time to mania for either dysphoric or euphoric patients.

Time to any mood episode or premature discontinuation

For the overall sample, there was no difference between initially euphoric and dysphoric patients on time to any mood episode or premature discontinuation. Among both euphoric and dysphoric patients, maintenance treatment with divalproex was superior to lithium in delaying time to any mood episode or premature discontinuation (euphoric: Wilcoxon p=0.036; dysphoric: Wilcoxon p=0.042). Both initially euphoric and initially dysphoric patients treated with placebo demonstrated an intermediate effect that was not significantly different from divalproex or lithium, although in both cases placebo was numerically superior to lithium: initially euphoric patients, placebo vs lithium (p=0.233), placebo vs divalproex (p=0.349); initially dysphoric patients, placebo vs lithium (p=0.093), placebo vs divalproex (p=0.834).

Time in study

There was no overall difference in the time in the study between initially euphoric (mean=186.9 days) and initially dysphoric (mean=174.6. days) patients. Initially, euphoric patients treated with divalproex continued in the maintenance phase for a longer period of time (214.9 days) compared to initially euphoric patients treated with placebo (158.6 days; p=0.092), and significantly longer compared to initially euphoric patients treated with lithium (136.6 days; p=0.037). There was no significant treatment-related difference in the time in the study for initially dysphoric patients (156.9 days for lithium-treated, 188.4 for divalproex-treated, and 168.1 days for placebo-treated patients).

Mean change in MRS, DSS, and GAS scores

The randomization baseline scores and mean change during randomized treatment on the MRS, DSS, and GAS are presented for each of the three treatment groups and the two manic subtypes in Table 3. Baseline scores did not differ between euphoric and dysphoric groups, nor among the three randomized treatment groups for any measure. The randomization baseline scores were generally so low that subsequent changes that occurred during the maintenance phase were generally related to deterioration rather than improvement. Change in the MRS did not differ between euphoric and dysphoric groups, between any two of the treatment groups, nor was there a significant interaction between treatment and manic subtype. Similar results were observed when the two subscales of the MRS, the Manic Syndrome Scale and the Behavior and Ideation Scale, were analyzed separately. There was no treatment-related effect on DSS or GAS scores over the course of the trial in the initially dysphoric patients.

Initially euphoric patients treated with lithium had significantly more deterioration in DSS scores than did patients treated with placebo (F1,118=5.78, p=0.018) or with divalproex (F1,118=14.73, p<0.001). Similarly, initially euphoric patients treated with lithium demonstrated significantly more deterioration in GAS scores than did those treated with placebo (F1,109=4.00, p=0.048) or divalproex (F1,109=9.70, p=0.002). For GAS, there was also a significant interaction effect between drug (divalproex vs lithium) and mania subtype (F1,325=4.71, p=0.013).

Tolerability

There were significantly more premature discontinuations due to intolerance in the initially dysphoric group (15.7%) compared to the initially euphoric group (7.3%; p=0.032), although no specific adverse event was reported significantly more frequently by the initially dysphoric patients. Maintenance treatment with either mood stabilizer was associated with increased intolerance in the initially dysphoric patients, as 23.2% of the initially dysphoric patients who received lithium maintenance therapy and 17.1% of those treated with divalproex maintenance therapy discontinued prematurely due to intolerance compared to 4.8% of those treated with placebo (p=0.003 and 0.02, respectively; Table 2). Significantly more initially euphoric patients treated with lithium (18.2%) discontinued prematurely due to intolerance compared to placebo (0%; p=0.03). There was no significant increase in intolerance-associated premature discontinuations in the initially euphoric subjects treated with divalproex compared with placebo (Table 2). There were no significant treatment differences for any adverse events reported by either the initially dysphoric or euphoric subjects. Significantly fewer initially euphoric patients discontinued prematurely due to depression when treated with divalproex (7.1%) compared to placebo (22.6%; p=0.04; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

It has been previously noted that the polarity of the index episode predicts the polarity of relapse in maintenance studies (Calabrese et al, 2004); mania begets mania, and depression begets depression. The data presented herein suggest for the first time that the dysphoric vs euphoric nature of mania predicts long-term tolerability and spectrum of efficacy. Dysphoria increased discontinuations due to side effects on both lithium and divalproex, whereas divalproex was more effective than lithium, but not placebo, in delaying depressive episodes in initially euphoric patients.

Previous acute treatment trials identified dysphoric mania as differentially more likely to respond to divalproex than to lithium (Secunda et al, 1985; Himmelhoch and Garfinkel, 1986; Freeman et al, 1992; Swann et al, 1997). These are the first randomized data to address maintenance phase outcomes in patients initially characterized as dysphoric. In exploratory analyses of predictors of lithium response in other recent studies of lithium as maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder, an initial mixed mania presentation did not predict unfavorable response to lithium, whereas indices of greater overall severity did predict poorer lithium response (Tohen et al, 2002; Ketter et al, 2003; Bowden et al, 2003b). The current results provide further support of greater illness severity as a predictor of poor lithium maintenance response, and therefore suggest a somewhat different set of predictors of response to lithium in maintenance phase treatment than in acute mania treatment.

Both drugs were significantly less well tolerated compared with placebo in the initially dysphoric manic patients. This is the first report of differential tolerability in long-term treatment between dysphoric and euphoric manic patients, with significantly worse tolerability in the dysphoric patients. It is possible that a generic contribution to the generally poorer outcomes reported with dysphoric mania is related to symptoms that are prominent in mixed mania, for example, irritability, physiological distress, autonomic overactivity, and anxiety (Swann et al, 2001; Andreasen and Grove, 1982). Such symptoms might result in increased subjective awareness of any dysphoric feelings, whether or not consequent to drug therapy.

Among the initially euphoric manic patients, divalproex was more effective on indices of depression, both assessed as time to development or mean depressive symptomatology during maintenance treatment, as well as on GAS score. Additionally, divalproex was better tolerated than lithium among the initially euphoric mania patients. The combination of greater tolerability of divalproex and greater efficacy in controlling depressive symptoms likely contributed to the significantly better overall maintenance outcome of initially euphoric patients treated with divalproex than with lithium or placebo.

Lithium has been reported efficacious in numerous early acute bipolar depression studies (Zornberg and Pope, 1993). Two recent maintenance studies have reported that lithium was not superior to placebo in delaying a new depressive episode, whereas lamotrigine was superior to placebo, with similar results in a combined analysis (Bowden et al, 2003a; Calabrese et al, 2003; Goodwin et al, 2004). An earlier maintenance study of lithium indicated an increased rate of depressive episodes in both rapid cycling and nonrapid cycling patients compared with placebo (Dunner et al, 1976), and a crossover study indicated little long-term benefit on depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder (Denicoff et al, 1994). However, a plausible mechanism for the worsening of depression, we observed in the initially euphoric manic patients treated with lithium is not self-evident. The consistently observed motor slowing consequent to lithium use in healthy control and bipolar patients might contribute to higher depression scores in patients who are no longer in a manic episode, with its attendant elevated energy and hyperactivity (Shaw et al, 1987; Swann et al, 2002).

Several long-term bipolar studies have demonstrated that the key to improved long-term outcome in bipolar disorder is continued mood-stabilizer therapy (Revicki et al, 2005; Keck et al, 1998; Weiss et al, 1998). One 12-month naturalistic comparison of divalproex vs lithium demonstrated no long-term outcome differences between subjects treated with divalproex vs lithium, but did demonstrate substantially lower total medical costs and better functional outcomes for those subjects that continued either divalproex or lithium therapy compared to those who discontinued therapy (Revicki et al, 2005). The present results regarding long-term tolerability in initially dysphoric manic patients warrant increased attention by psychiatrists to adherence to treatment, and the interplay between adverse effects and efficacy of treatment regimens.

There are several limitations of these a priori planned analyses. Relatively sparse data were available from the open acute treatment phase. The criteria for randomization were deliberately set to select for randomization a group of patients nearer remission than response (Bowden et al, 2000). Perhaps more important for the time to event analyses, the definitions of manic or depressive relapse required a full episode. This decision, a deliberate one, intended to avoid blurring the difference between a full episode and some worsening of continuation symptomatology from the initial index episode, contributed to a lower than anticipated rate of manic or depressive events, thereby reducing power. This design consideration did not affect analyses such as time in study or change in manic or depressive symptomatology, probably contributing to the greater sensitivity of these analyses. Since DSM-III R criteria are employed by the SCID, thereby not differentiating between euphoric and mixed manic episodes, we were unable to analyze the subset of patients with initially explicitly DSM-IV mixed manic states. However, the DSM-IV criteria are generally criticized as overly restrictive, and definitions similar to those employed here have been recommended (Swann et al, 1997; Akiskal et al, 2000). The design was an unbalanced one, with twice the proportion of patients treated with divalproex as with placebo or lithium. This reduced power for lithium-placebo comparisons. A major purpose of the overall study was to develop data for regulatory consideration of divalproex maintenance therapy for bipolar I disorder. The lithium arm was included for purposes of assay sensitivity, comparison with divalproex, and determination of lithium performance in maintenance therapy under current diagnostic schemes and methods, particularly avoiding abrupt discontinuation of lithium, now understood to worsen near term illness course in bipolar disorder (Cavanagh et al, 2004). Acute treatment was not randomly assigned, but was selected by the treating physician, which may have contributed to a possible selection bias. Finally, the criteria we employed to establish groups of euphoric and dysphoric manic patients differ from the syndromal criteria of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), and identify a broader proportion of manic patients as dysphoric in character, consistent with most recent studies (Swann et al, 1997; Baldessarini et al, 2003; Cassidy and Carroll, 2001).

The results are of substantial clinical and heuristic relevance despite the above limitations. These are the first randomized, blinded maintenance data to indicate that patients with dysphoric manic features are particularly sensitive to adverse effects from at least divalproex and lithium. Plausible reasons that could be tested in future studies are that dysphoric symptomatology may include heightened subjective sensitivity to adverse drug effects, or that the neurobiology of dysphoric mania predisposes to higher adverse effect burden at a given treatment dosage (Swann et al, 1993). They provide unanticipated evidence on maintenance outcomes for initially euphoric mania patients, with lithium appearing to worsen depression, whereas divalproex and placebo maintained depressive symptomatology at the level present at randomization. Despite the ability of divalproex to treat dysphoric mania more efficaciously than lithium, it did not provide greater prophylactic benefit than lithium in initially dysphoric patients. Despite lithium's established efficacy in euphoric mania acutely, it was relatively less efficacious than divalproex in prophylaxis for the initially euphoric manic patients. Thus, the results serve as an important reminder that treatment efficacy in acute mania does not necessarily predict treatment efficacy, or prophylaxis for emergent depressive symptoms.

References

Akiskal HS, Bourgeois ML, Angst J, Post R, Moller H-J, Hirschfeld R (2000). Re-evaluating the prevalence of and diagnostic composition within the broad clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders. J Affect Disord 59: S5–S30.

American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised 3rd edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

Andreasen NC, Grove WM (1982). The classification of depression, traditional versus mathematical approaches. Am J Psychiatr 139: 45–52.

Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, Wilson M, Calabrese J, Chengappa R, Keck Jr PE et al. (2003). Olanzapine versus placebo in acute mania: treatment responses in subgroups. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23: 370–376.

Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F et al (2000). A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 481–489.

Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Asghar SA, Hompland M et al (2003a). A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 392–400.

Bowden CL, Ketter TA, Calabrese JR, Goldberg J, Suppes T, Frye M et al (2003b). Predictors of response to maintenance treatment with lithium, lamotrigine, and placebo in bipolar disorder patients [abstract]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting 2003.

Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Behnke K, Mehtonen O-P et al (2003). A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 1013–1024.

Calabrese JR, Vieta E, El-Mallakj R, Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Elhaj O et al (2004). Mood state at study entry as predictor of risk of relapse and spectrum of efficacy in bipolar maintenance studies. Biol Psychiatry 56: 857–873.

Cassidy F, Carroll BJ (2001). The clinical epidemiology of pure and mixed manic episodes. Bipolar Disord 3: 35–40.

Cavanagh J, Smyth R, Goodwin GM (2004). Relapse into mania or depression following lithium discontinuation: a 7-year follow-up. Acta Pscychiatr Scand 109: 91–95.

Denicoff KD, Blake KD, Smith-Jackson EE, Syed AO, Leverich GS, Post RM et al (1994). Morbidity in treated bipolar disorder: a one-year prospective study using daily life chart ratings. Depression 2: 95–104.

Dunner DL, Stallone F, Fieve RR (1976). Lithium carbonate and affective disorders V: a double-blind study of prophylaxis of depression in bipolar illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33: 117–120.

Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, Swann AC (1992). A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatr 149: 108–111.

Goodwin GM, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Grunze H, Kasper S, White R et al (2004). A pooled analysis of 2 placebo-controlled 18-month trials of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance in bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 432–441.

Himmelhoch JM, Garfinkel ME (1986). Sources of lithium resistance in mixed mania. Psychopharmacol Bull 22: 613–620.

Keck Jr PE, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM et al (1998). 12-month outcome of patients with bipolar disorder following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. AM J Psychiatry 155: 646–652.

Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Clayton PJ et al (1986). Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. JAMA 255: 3138–3142.

Keller MB (1988). The course of manic-depressive illness. J Clin Psychiatry 49(Suppl): 4–7.

Ketter T, Bowden C, Calabrese J, Goldberg J, Suppes T, Frye M et al (2003). Clinical predictors of response to treatment in bipolar I disorder [abstract]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting 2003. p 85.

Revicki DA, Hirschfeld RMA, Ahearn EP, Weisler RH, Palmer C, Keck PE (2005). Effectiveness and medical costs of divaproex versus lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder: results of a naturalistic clinical trial. J Affec Disord (in press).

SAS Institute I (1989). SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 6, 4th edn. SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC.

Secunda S, Katz MM, Swann AC, Koslow SH, Maas JW, Chang S et al (1985). Mania: diagnosis, state measurement, and prediction of treatment response. J Affect Disord 8: 113–121.

Secunda S, Swann AC, Katz MM, Koslow SH, Croughan J, Chang S (1987). Diagnosis and treatment of mixed mania. Am J Psychiatry 144: 96–98.

Shaw E, Stokes P, Mann J, Manevitz Z (1987). Effects of lithium carbonate on the memory and motor speed of bipolar outpatients. J Abnorm Psychol 96: 64–69.

Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbons M, First MB (1990). Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III-R. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Dilsaver SC, Morris DD (1999). Differential effect of number of previous episodes of affective disorder on response to lithium or divalproex in acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 156: 1264–1266.

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese RJ, Dilsaver CS, Morris MJ (2002). Pattern of response to divalproex, lithium, or placebo in four naturalistic subtypes of mania. Neuropsychopharmacol 26: 529–536.

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, Calabrese JR, Petty F, Small J et al (1997). Depression during mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 37–42.

Swann AC, Janicak PL, Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Dilsaver SC, Morris DD et al (2001). Structure of mania: depressive, irritable, and psychotic cluster with different retrospectively-assessed course patterns of illness in randomized clinical trial participants. J Affect Disord 67: 123–132.

Swann AC, Secunda SK, Katz MM, Croughan J, Bowden CL, Koslow SH et al (1993). Specificity of mixed affective states: clinical comparison of dysphoric mania and agitated depression. J Affect Disord 28: 81–89.

Tohen M, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Jacobs T, Baker RW et al (2003). Olanzapine versus placebo for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder [abstract]. American Psychiatric Association Annual meeting 2003, p 197.

Tohen M, Bowden C, Greil W, Jacobs T, Baker RW, Evans AR et al (2002). Olanzapine in relapse prevention of bipolar disorder [abstract]. Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. p 94.

Turvey CL, Coryell WH, Anrdt S, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J et al (1999). Polarity sequence, depression, and chronicity in bipolar I disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 187: 181–187.

Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, Soto JA, Wyner D, Tohen M et al (1998). Medication compliance among patients with bipolar disorder and substance use. J Clin Psychiatry 59: 172–174.

Zornberg GL, Pope Jr HG (1993). Treatment of depression in bipolar disorder: new directions for research. J Clin Psychopharm 13: 397–408.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL. The following members of the Divalproex Maintenance Study Group took part in this study: Paul E Alexander, MD, Psychiatric Foundation for Research and Education, Warwick, RI; Charles Bowden, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX; Joseph R Calabrese, MD, Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH; Jeffery Clothier, MD, University of Arkansas Medical School, Little Rock, AR; Robert Cooke, MD, Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, Toronto, Canada; William Coryell, MD, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA; James C-Y Chou, MD, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY; Scott Crow, MD, University of Minnesota Hospital, Minneapolis, MN; Pedro Delgado, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ; John Downs, MD, University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN; Dwight Evans, MD, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL (currently of University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA); Arlene F Frank, MD, Brookside Hospital, Nashua, NH; Robert Gerner, MD, University of California Center for Mood Disorders, Los Angeles, CA; William J Giakas, MD, Rockford Psychiatric Medical Services, Rockford, IL; Ira David Glick, MD, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; Robert MA Hirschfeld, MD, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX; Steven Parker James, MD, Yorba Hills Medical Plaza, Yorba Linda, CA; Philip G Janicak, MD, Illinois State Psychiatric Institute, Chicago, IL; James W Jefferson, MD, Dean Foundation for Health, Research, and Education, Madison, WI; Paul E Keck Jr, MD, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH; Barbara L Kennedy, MD, PhD, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; K Ranga Rama Krishnan, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Susan McElroy, MD, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH; B Raj Nakra, MD, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO; Henry A Nasrallah, MD, Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH; Charles B Nemeroff, MD, PhD, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA; William M Patterson, MD, Birmingham Research Group, Inc., Birmingham, AL; Frederick Petty, MD, PhD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX; Alan H Rosenbaum, MD, Comprehensive Psychiatric Services, Farmington Hills, MI; David Vincent Sheehan, MD, University of South Florida Psychiatry Center, Tampa, FL; Alan C Swann, MD, University of Texas Medical School at Houston, Houston, TX; Craig S Risch, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Richard L Wang, MD, Milwaukee County Medical Complex, Milwaukee, WI; Adel Wassef, MD, University of Texas-Houston Health Science Center, Houston, TX; Richard H Weisler, MD, Raleigh, NC; Phillip Wilner, MD, Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, New York City, NY; Patricia J Wozniak, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL.

Dr Bowden is a consultant for Abbott Laboraties, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Sanofi Aventis, and Eli Lilly. He has research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Eli Lilly

Dr Collins is an employee of Abbott Laboratories.

Dr McElroy is a consultant to Abbott Laboratories and a member of the company's Speakers Bureau and Divalproex Advisory Board. She has also received research grants from Abbott Laboratories and Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr Calabrese is a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, a member of the Divalproex Advisory Board, and has received research grants support from Abbott Laboratories.

Dr Swann has received grant support from Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, and Shire Laboratories. He has served as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer Laboratories, Shire Laboratories, UCB Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He has served on Speakers' Bureaus for Abbott Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer Laboratories.

Dr Weisler has received grant support from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Glaxo SmithKline, Abbott, Merck, Organon, Biovail, Shire, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Astra Zeneca Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Wyeth Ayerst, Solvay, Novartis, Schwabe, TAP Pharmaceutical, Synaptic Pharmaceutical Incorporated, Eisai, UCB Pharma, Inc., Cephalon, Lundbeck, Forest, and Pharmacia. He has served as a consultant/advisor to Pfizer, Glaxo Smithkline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Biovail, Lilly, Wyeth Ayerst, Shire, Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Forest, Solvay, AstraZeneca, Cephalon, and Abbott Laboratories. He is a stockholder of Merck, Pfizer, and Bristol Myers Squibb.

Dr Wozniak is an employee of Abbott Laboratories.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bowden, C., Collins, M., McElroy, S. et al. Relationship of Mania Symptomatology to Maintenance Treatment Response with Divalproex, Lithium, or Placebo. Neuropsychopharmacol 30, 1932–1939 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300788

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300788

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Treatment of Mixed Features in Bipolar Disorder: an Updated View

Current Psychiatry Reports (2020)

-

Consider second-generation antipsychotics for the management of mixed states in bipolar disorder

Drugs & Therapy Perspectives (2016)

-

Diagnosis, Epidemiology and Management of Mixed States in Bipolar Disorder

CNS Drugs (2015)

-

Efficacy of pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder: a report by the WPA section on pharmacopsychiatry

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2012)

-

The Pharmacogenetics of Lithium Response Depends upon Clinical Co-Morbidity

Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy (2007)