Abstract

Depression in the elderly is a major public health problem as untreated depression adversely impacts comorbid illnesses. It is important to develop safe and effective antidepressant therapies for older individuals. We performed a systematic review of all published randomized, placebo-controlled antidepressant medication trials in populations over age 55 years. Papers were obtained via MEDLINE (1966–August 2003) and PSYCINFO (1872–August 2003). Unpublished trials, trials examining nonpharmacologic interventions, and papers reporting post hoc analyses were not included in this review unless they provided new insights. A total of 18 placebo-controlled trials examining acute efficacy met our criteria. The combined sample size in these studies was 2252. The mean sample size was 51 (range 20–728) and mean trial duration was 7 weeks. A total of 12 trials examined tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), five trials examined selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), two trials examined bupropion, and one trial examined mirtazapine. There were no published trials of venlafaxine or nefazodone. In all, 71.5% of trials reported significantly greater efficacy with drug than placebo. In conclusions, there is a paucity of published controlled antidepressant trials in the elderly. Most published studies examine small sample sizes and do not include common comorbid conditions. Efficacy studies examining relapse prevention are lacking. Large placebo response rates, lack of controlled head to head comparisons, and other methodological design differences make crosstrial comparisons difficult. Large simple studies are urgently needed to address the unmet needs for data on safety and efficacy of antidepressants in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Depression in the elderly population is common in many settings and has become recognized as a significant public health concern (Reynolds et al, 1993; Lebowitz et al, 1997). The prevalence of major depression ranges from 6 to 9% of geriatric primary care patients, and is higher on medical in-patient services or in nursing homes (Katon and Schulberg, 1992). Depression is further associated with poorer outcomes of medical illnesses (Rovner et al, 1991; Frasure-Smith et al, 1993; Nemeroff et al, 1998; Jiang et al, 2001) and increased suicide rates (Conwell et al, 2002). Despite its associated morbidity and mortality, there are few published antidepressant placebo-controlled trials in the elderly.

Studies in younger populations may not generalize to the older population as depression in the elderly differs from depression in younger individuals. When compared with younger cohorts, depressed elders are less likely to have a family history of mood disorders and more likely to have findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging (Krishnan et al, 1997). Depressed elders are also more likely to have serious medical conditions and cognitive deficits complicating their treatment. The presence of cerebrovascular disease, various medical comorbidities, and mild cognitive impairment or dementia may each impact outcomes, but there is only limited evidence for antidepressant efficacy in the ‘general’ elderly population, much less these specific groups.

In this review, we focus our discussion on published randomized, placebo-controlled trials in depressed elderly subjects, examining both study results and methodological issues. We use these studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of trials to date, as well as to discuss methodological issues affecting future trial design.

METHODS

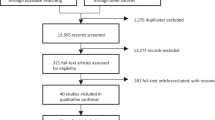

Comprehensive searches of the medical literature in MEDLINE (1966–2003) and PSYCINFO (1872–2003) were conducted. The following medical subject headings (MeSH) for MEDLINE were used in the search: placebo, antidepressant agent, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). Individual antidepressant drug names were also used as a term heading. All searches were age-limited. In addition to the formal literature search, manual crossreferencing of trials, review articles, meta-analyses, and expert opinion was also used to identify all randomized controlled trials examining antidepressant use in the elderly.

To be included in this report, studies had to meet specific inclusion criteria. These included (1) randomization of subjects, (2) placebo control arm, and (3) study duration of 4 weeks or greater. They had to include subjects (1) exclusively age 55 and over and (2) with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or unipolar depression using defined criteria, such as DSM. Studies were excluded from this review if they (1) evaluated psychotic depression, (2) included subjects with other psychiatric diagnoses, such as dementia, (3) were maintenance studies, (4) used adjunctive treatments, such as psychotherapy, sleep deprivation, or electoconvulsive therapy, or (5) if primary outcomes of the study were not related to treatment (such as electrocardiogram changes or weight).

There are very few published placebo-controlled trials in older depressed populations. For some agents in common use, such as venlafaxine and escitalopram, there are no published trials. In some cases, reports of placebo-controlled trials have been reported in professional meetings, but it is difficult to evaluate those limited data in the absence of a critical peer review; we do not include them in this report. However, to present a balanced picture, we briefly discuss the available evidence supporting the use of antidepressants that do not have published placebo-controlled trials.

For studies presenting outcomes as dichotomous measures, such as the percentage of patients classified as responders to therapy, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and its 95% confidence interval (Cook and Sackett, 1995). NNT gives the number of patients who must be treated in order to see that one patient obtains that outcome. We calculated this value for each study presenting dichotomous outcomes. In order to estimate differences between antidepressant classes and for antidepressants overall, we pooled subjects across studies.

Methods of defining response and remission vary across studies; however, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (Hamilton, 1960) and Clinical Global Impressions – Improvement Scale (CGI-I) (Guy, 1976) were the most commonly used. We examined these measures separately. CGI-I was defined as subjects showing any improvement, although some studies limited the CGI-I definition of improvement to a score of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved). For the HAM-D scale, response was defined as a 50% or greater decrease in score; this was more commonly reported and more consistently used than definitions of response (which were defined as a final HAM-D score below some cutoff, typically 7–10).

RESULTS

There is heterogeneity of sampling and trial design across studies, making it difficult to compare many studies with each other. One issue addressed in past reviews (Gerson et al, 1999) is the question of an appropriate inclusion age. To include the largest number of studies, we set an inclusion age of 55, but divided studies by inclusion age (greater than 55 or greater than 60). There are also differences across studies in diagnostic schemes, entry criteria, and the subject population's location, in addition to methodological variations in dosing strategies and placebo lead-in periods (Table 1).

Many scales were used to measure outcomes (Table 2). These scales measure different symptoms and are applied in a variety of ways. Even for the more commonly used scales, such as HAM-D, studies may use a variety of different definitions of treatment response or remission. As HAM-D is the most commonly used scale for the studies reported in this review, we discuss this as a primary outcome measure (Table 3). Other results, including rating scale cutoff measures of response or remission, are considered secondary outcomes measures (Table 4).

Tricyclic Antidepressants

The most commonly prescribed TCAs have been studied in the elderly; most trials have focused on imipramine or nortriptyline, although one examined amitriptyline (Branconnier et al, 1982). These studies used a variety of diagnostic criteria (including the Primary Affective Disorders – Depression Checklist (Feighner et al, 1972), Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer et al, 1977), and DSM-III or IIIR) and a variety of instruments as secondary outcome measures (such as the Geriatric Depression Scale, the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; Table 4). Most required a minimum baseline level of depression severity (typically an HAM-D score above 16–19), and reported a mean sample age in the 60s, with a few exceptions reporting ages of 72 (Schweizer et al, 1998) or 84 (Katz et al, 1990).

All published trials with an inclusion age of 60 years, ranging from 4 to 8 weeks, concluded that imipramine was significantly superior to placebo (Gerner et al, 1980; Cohn et al, 1984; Merideth et al, 1984; Wakelin, 1986; Schweizer et al, 1998). All of these studies compared imipramine and placebo with another antidepressant agent, either trazodone (Gerner et al, 1980), fluvoxamine (Wakelin, 1986), buspirone (Schweizer et al, 1998), or the tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative, nomifensine (Cohn et al, 1984; Merideth et al, 1984) (Table 1). None of these studies reported a significant difference between active agents.

There were three small trials examining imipramine's efficacy in populations over 55. These compared imipramine with two doses of bupropion (Branconnier et al, 1983; Kane et al, 1983) and another TCA, doxepin (Jarvik et al, 1982). The Jarvik study was descriptive; doxepin and imipramine showed comparable improvement greater than placebo, but significance levels were not reported. The two studies including bupropion reported conflicting results: one study found that the active drugs had comparable changes in HAM-D significantly greater than placebo (Branconnier et al, 1983), while the other found no significant bupropion–placebo differences on the HAM-D measure (Kane et al, 1983). No study reported a difference in efficacy between antidepressant agents on HAM-D change.

These findings were replicated in the secondary outcomes (Table 4) by the number of subjects ranked as ‘improved’ on the CGI-I scale (Cohn et al, 1984; Merideth et al, 1984; Schweizer et al, 1998). Schweizer et al additionally examined response, as defined by a 50% or greater decrease in HAM-D; both imipramine and buspirone subjects were significantly more likely to respond than placebo subjects. Active agents were also more likely than placebo to produce improvement as measured by BPRS (Cohn et al, 1984) or BDI (Gerner et al, 1980). The study of imipramine, bupropion, and placebo (Kane et al, 1983) found no difference on the HAM-D or CGI scale but did detect a significant difference using the Zung Depression Scale with a greater improvement in the imipramine arm over both bupropion arms and the placebo arm. The only other scale demonstrating a differential effect between active agents was the HAM-A scale, which demonstrated a greater reduction in severity for those individuals on imipramine when compared with those on trazodone or placebo (Gerner et al, 1980).

Three published trials examined the efficacy of nortriptyline. Katz et al (1990) studied a small cohort of medically frail, institutionalized elders and reported a significantly greater decrease in HAM-D for those receiving nortriptyline. This improvement was also seen on CGI: 58% of subjects on nortriptyline had a score of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved), while only 9% of those receiving placebo exhibited this level of improvement (Table 4). A difference between agents was not seen using GDS.

The two remaining studies of nortriptyline examined a comparator antidepressant in addition to placebo, phenelzine (Georgotas et al, 1987), or moclobemide (Nair et al, 1995), a reversible MAO-A inhibitor. The study by Nair et al showed that only imipramine, but not moclobemide, had a significant effect on HAM-D beyond placebo (Table 3). A similar finding was seen in a subanalysis of those achieving remission, as defined by a final HAM-D less than 10 (Table 4).

The Georgotas study took a different approach, examining improvement in individual HAM-D items. They found that nortriptyline and phenelzine were superior to placebo in reducing the HAM-D scores for the items of depressed mood, guilt, suicidality, agitation, anxiety, and loss of energy. The only item where nortriptyline was more effective than phenelzine or placebo was in alleviating middle/late insomnia.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

The only trial examining MAOIs in elderly subjects compared phenelzine with nortriptyline and placebo (Georgotas et al, 1987), and is described above. Phenelzine was generally found to be as effective in treating depressive symptoms as nortriptyline, and more effective than placebo.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs are generally considered to be first-line treatments of depression. They are prescribed more often for elderly patients than any other psychotropic (Lasser and Sunderland, 1998), and are the antidepressant of choice for many practitioners (Rothera et al, 2002). Placebo-controlled studies are not available for citalopram and escitalopram, although comparison studies in the elderly are available, including a study of citalopram in an elderly depressed population with and without dementia (Karlsson et al, 2000). A placebo-controlled trial of citalopram in the elderly was conducted, but has not yet been published.

Like studies of TCAs, SSRIs were initially studied in small samples. An early trial found that fluvoxamine and imipramine were both superior to placebo (Wakelin, 1986). Another study in medical in-patients (Evans et al, 1997) found no significant difference in treatment response between subjects receiving fluoxetine and placebo. This study examined a small population of older medically ill subjects; either of these factors may have contributed toward the negative outcome.

Fluoxetine has been studied in a large randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial in a community population (Tollefson et al, 1995). This study examined over 500 subjects and compared 20 mg of fluoxetine with placebo over a 6-week period with a 1-week placebo lead-in (Table 1). The primary outcome on the HAM-D scale was negative: subjects who received fluoxetine did not exhibit a significantly greater mean HAM-D change than did those receiving placebo (Table 3). The secondary outcomes of the rate of subjects achieving response (HAM-D reduction of >50%) or remission (end point HAM-D of ⩽8) were statistically significant (Table 4) and more encouraging. The most robust difference reported remission rates as defined by an HAM-D score of 8 or less, but only 32% of fluoxetine subjects compared with 19% of placebo subjects achieved this level of response. The rate of subjects showing improvement on CGI also favored fluoxetine.

The largest multicenter, placebo-controlled trial in the elderly compared sertraline with placebo in 747 subjects (Schneider et al, 2003). This 8-week trial started with subjects at a daily dose of 50 mg, with the option to increase the dose to 100 mg after 4 weeks. The subjects who received sertraline exhibited greater and statistically significant improvement on the primary outcomes, with HAM-D, CGI-I, and CGI-S. Unfortunately, the size of the effect based on the HAM-D score was not large; at end point there was only a 1.5 point adjusted mean difference in HAM-D score between groups (Table 3). An alternative measurement of response, 50% or greater improvement in HAM-D, found a response rate (35%) comparable to that seen in fluoxetine (44%) (Tollefson et al, 1995) (Table 4). Improvements in CGI-I were also comparable between sertraline (45%) and fluoxetine (44.5%). Placebo responses for each measure were similarly comparable between studies.

There was one trial of paroxetine in residential elderly subjects with DSM-IV-defined minor depressive disorder (Burrows et al, 2002). A total of 20 subjects were examined; entrance criteria required a minimum age of 80 years, an MMSE>10, and a score above 3 on the seven-item depression subscale of the Cornell Scale. Baseline HAM-D scores were 13.8 for the paroxetine arm and 15.4 for the placebo arm. Both groups had comparable responses; the authors could not demonstrate a significant difference in outcome between the two arms on either the HAM-D or CGI-I scale.

Other Antidepressant Agents

Bupropion

Although two studies have compared bupropion with imipramine and placebo (Branconnier et al, 1982; Kane et al, 1983), only a total of 57 subjects were in the bupropion treatment arms and approximately half of those received a low bupropion dose of 150 mg daily. An examination of these trials shows that while one study found a difference between active agents and placebo (Branconnier et al, 1982), the other did not (Kane et al, 1983). A comparison trial of bupropion SR and paroxetine has also been reported (Weihs et al, 2000), demonstrating that both groups showed improved scores on depression rating scales. Unfortunately, this study did not include a placebo arm and only 48 of 100 subjects received bupropion SR.

Mirtazapine

One study compared mirtazapine with trazodone and placebo (Halikas, 1995). The authors demonstrated that the group receiving mirtazapine had significantly lower HAM-D scores at the 6-week end point than did the placebo group. Other than this one study, there are no other published placebo-controlled trials of mirtazapine in the elderly. Mirtazapine has also been compared with amitriptyline (Hoyberg et al, 1996) and paroxetine (Schatzberg et al, 2002). Although both studies found comparable efficacy between agents, in the paroxetine–mirtazapine comparison, the mirtazapine group appeared to have a faster decrease in mean HAM-D (17 item) scores. A similar finding was not demonstrated in the comparison with amitriptyline.

Venlafaxine

There are no published placebo-controlled trials of venlafaxine in depressed elderly populations, although there are data supporting its role in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in the elderly (Katz et al, 2002). Available data supporting its role in depression include open-label trials and clinical trials comparing venlafaxine with other antidepressants, but not placebo. Venlafaxine has been compared against clomipramine and trazodone (Smeraldi et al, 1998), nortriptyline (Gasto et al, 2003), and dothiepin, a TCA used in Europe (Mahapatra and Hackett, 1997). In these studies, venlafaxine exhibited superiority to trazodone (Smeraldi et al, 1998), but otherwise the response rate was comparable between venlafaxine and its comparators.

Nefazodone

Nefazodone has not been systematically studied in late-life depression. Data from a prospective, observational study suggest that it may be a reasonably well-tolerated and effective antidepressant in this population (Saiz-Ruiz et al, 2002).

Duloxetine

There are currently no published trials in the elderly for duloxetine, an agent that acts by inhibiting serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. A subanalysis of elderly patients who participated in clinical trials is underway, but not yet published.

Other antidepressant agents

In addition to the trials described in the TCA section, there have been two other studies of agents not currently used in the United States. One compared nomifensine with placebo in elderly depressed medical in-patients (Jansen and Siegried, 1984). This study replicated findings in other studies comparing nomifensine with imipramine and placebo (Cohn et al, 1984; Merideth et al, 1984). The authors demonstrated that subjects who received nomifensine were significantly more likely to demonstrate a reduction in HAM-D compared with placebo subjects.

The other study examined low-dose lofepramine, a TCA used in Europe, in a small group of medical in-patients (Tan et al, 1994). This study included no HAM-D data. The primary outcome was change in MADRS; however, they could not demonstrate a statistically different effect between arms after 4 weeks of treatment.

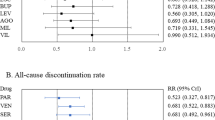

Number Needed to Treat Analyses

Not all studies reported categorical outcome data, instead relying on continuous outcomes alone or not reporting ratios of responders to nonresponders. More studies reported outcomes of improved on CGI-I (Kane et al, 1983; Cohn et al, 1984; Merideth et al, 1984; Katz et al, 1990; Nair et al, 1995; Tollefson et al, 1995; Schweizer et al, 1998; Schneider et al, 2003) than outcomes of response or remission on HAM-D (Nair et al, 1995; Tollefson et al, 1995; Evans et al, 1997; Schweizer et al, 1998; Schneider et al, 2003). We did not include the study of minor depression (Burrows et al, 2002) in these analyses. We also did not include buspirone as an antidepressant, although we did include data from the imipramine and placebo arms of that study (Schweizer et al, 1998). Test results for individual studies are shown in Table 4.

Number needed to treat estimates were similar within each drug class regardless of which outcome measure was examined. For TCAs, using any improvement on CGI as the outcome, NNT was 5 (95% CI 3,7); using at least a 50% reduction in HAM-D as the outcome, NNT was 5 (95% CI 3, 9). This means that in order to have one patient respond to a TCA, one would have to treat five patients. When the SSRI trials were combined, the CGI-I outcome resulted in an NNT=8 (95% CI 5,12); a similar result was seen when 50% reduction in HAM-D was the outcome, where NNT=8 (95% CI 5,11). As the confidence intervals between TCAs and SSRIs overlap, these data do not support that one drug class is more effective than another.

Finally, NNT was calculated combining all antidepressant agents. To get improvement as measured by CGI-I, NNT=7 (95% CI 5, 9). To obtain a 50% or greater reduction in HAM-D, NNT=8 (95% CI 5,11). Thus, one must treat approximately seven patients to have one patient who improves by CGI. Alternatively, one must treat eight patients to have one who exhibits a 50% or greater reduction on HAM-D.

DISCUSSION

These studies support the clinical observation that antidepressants can effectively treat depression in the elderly, the same conclusion reached by others using meta-analytic techniques (Mittmann et al, 1997; Wilson et al, 2001). Our NNT analysis demonstrated that one must treat eight patients to have one subject achieve even a 50% reduction in depressive symptoms; thus, while antidepressants are more effective than placebo, a significant number of patients will not respond. These conclusions are complicated by a high placebo response rate, which may impact even well designed, large trials (Tollefson et al, 1995; Schneider et al, 2003).

Is there a difference in efficacy between antidepressant classes? Studies including active comparators did not show differences between active agents, but many of these were underpowered to detect a difference (Koppel et al, 2003). Our NNT analyses also demonstrate no significant difference between drug classes, although given the available trials, only TCAs and SSRIs could be compared. Although TCAs had a lower NNT to observe a response than did SSRIs (5 compared with 8), the fact that the 95% confidence intervals overlap makes this finding nonsignificant. It is also important to consider that many of the TCA trials were conducted in the 1980s, while the SSRI studies ran in the 1990s. This may impact the placebo response rate, which has been observed to increase over time (Walsh et al, 2002), and so may impact NNT.

A limitation for many of these studies is that they are efficacy trials, not effectiveness trials. That is, they examine antidepressant response in a narrowly defined patient population, typically excluding subjects for many reasons, such as comorbid psychiatric illnesses including psychosis, addictions or personality disorders, subjects with significant medical comorbidity, and subjects with poor treatment response histories. Thus the results of these studies do not necessarily generalize to ‘typical’ clinical populations where these comorbidities are commonplace.

Large trials in commonly used antidepressants utilizing few exclusion criteria are desperately needed. More research is needed into more efficacious antidepressant agents, reasons why individuals do not respond to current antidepressants, and better, evidence-based strategies for treating these individuals. Information answering some of these questions may be obtained through the STAR*D trial, which was designed to provide data on treatment strategies for patients who have not responded to initial antidepressant treatment (Fava et al, 2003; Rush et al, 2003).

Safety and Tolerability of Antidepressants in the Elderly Population

The safety and tolerability of antidepressants in elderly patients is a topic worthy of study in its own right. However, it is critical to consider in a discussion of antidepressant efficacy as tolerability may significantly impact clinical efficacy trials. Studies of medications with more common or severe side effects may result in a higher rate of early subject withdrawal; if enough subjects withdraw before study completion, it can make the study's validity questionable. Such information is valuable for the clinical care of older patients, as side effects may be more common than seen in younger patients due to the decreased rate of drug metabolism and medical comorbidity. As SSRIs are currently the most commonly used antidepressants, it is worth considering tolerability and adverse events that occurred in the large trials of fluoxetine and sertraline.

The fluoxetine study (Tollefson et al, 1995) found that 11.6% of subjects receiving fluoxetine 20 mg withdrew early for adverse events, compared with 8.6% of those on placebo; this difference was not statistically significant. The most common side effects occurring in at least 10% of patients that were significantly greater in the treatment arm included insomnia, nausea, diarrhea, anxiety or nervousness, anorexia, and dyspepsia. No life-threatening adverse effects were reported, and only one of 335 subjects treated with fluoxetine developed suicidal ideation while three of 336 placebo subjects developed suicidal ideation. Although there were significant reductions in heart rate and weight associated with fluoxetine, these differences did not appear to be clinically meaningful.

The flexible-dose study of sertraline (Schneider et al, 2003) reported that approximately 14% of subjects on sertraline withdrew early due to adverse events, although only 8% were judged by the investigators to be related to study drug. This is in contrast to the 4% withdrawal rate for adverse events in the placebo arm, 2% of which were judged to be related to the study drug; a statistical analysis of these differences was not reported. The most common side effects that occurred in at least 5% of patients that were significantly greater in the treatment arm included headache, diarrhea, nausea, sleep disturbances (either fatigue/somnolence or insomnia), and tremor. Although serious adverse events did occur in both arms, none were considered to be related to study drug. There were no remarkable changes in vital signs seen.

Information on side effects is critical for the appropriate management of our patients. However, the rigid inclusion/exclusion criteria used in efficacy trials limit its generalizability to most clinical practice. As safety data continue to be evaluated, it will be important to also examine the results of trials of antidepressants in old-old populations and populations with specific medical illnesses, such as the use of sertraline after acute myocardial infarction (Glassman et al, 2002).

Methodological Considerations for Antidepressant Trials in the Elderly

Some elements of trial design cannot be changed. For example, using a standardized definition of depression (such as the major depressive disorder from DSM-IV) is necessary to obtain a level of diagnostic uniformity and to obtain government approval for a specific indication. To supplement this definition and to provide a measure of disease severity, minimum scores on rating scales are also used. Although necessary, these definitions may be insufficient as depression in the elderly may have a different pathophysiology, different course, and different comorbidities (Lebowitz et al, 1997).

There is significant heterogeneity in geriatric depression, and current definitions of depression do not capture well the entire spectrum of depressive disorders. There is mounting evidence for significant minor or subsyndromal depressive disorders in older populations (Rovner et al, 1991; Katz et al, 1995), suggesting that depression is likely a spectrum rather than a set of discrete entities (Caine et al, 1993). Comorbid medical problems present other diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, but also opportunities to better understand the relationship between mood and medical outcomes. This is possible to quantify in a clinical trial, as there are a variety of scales available (de Groot et al, 2003). Depression in the context of cognitive impairment or dementia presents another complication and may be fundamentally different from depression in cognitively intact elderly (Olin et al, 2002a, 2002b). Studies in elderly depressed populations who are not healthy and cognitively intact are imperative.

Subject location

Location of subjects is a critical factor given that it may dictate illness severity, medical comorbidity, or level of cognitive function. It is also critical to examine interventions to treat depression in a variety of settings; depression is commonly seen in primary care practices, and interventions designed to address this problem that fit within the practice model are sorely needed. Some models have been proposed and studied (Mulsant et al, 2001), although different models may result in allowing for longer periods for subjects to achieve study outcomes (Thomas et al, 2002).

Most of the studies we report include subjects who reside in the community but receive care at a tertiary care facility. The two studies in medical in-patients both failed to differentiate active drug from placebo (Tan et al, 1994; Evans et al, 1997). The two studies in nursing home populations found differing results (Katz et al, 1990; Burrows et al, 2002), but this was complicated as one examined minor rather than major depression (Burrows et al, 2002).

Medical illnesses are not the only difference in subjects in various settings. Subjects in nursing homes may experience depression due to psychosocial reasons of less family support, bereavement, or loss of independence. These may also be issues for community dwelling elders. These factors also complicate treatment and so should also be considered.

Inclusion age and response of the old-old subjects

There was a greater ratio of negative studies in those with a minimum entry age of 55 years than in those with an entry age of 60 or over. Two of five (40%) studies with an entry age of 55, investigating a total of 70 subjects, reported negative results (Jarvik et al, 1982; Kane et al, 1983). In contrast, three of 12 studies (17%) with a minimum entry age of 60, investigating a total of 709 subjects, reported negative results on their primary outcome (Tan et al, 1994; Tollefson et al, 1995; Evans et al, 1997). One of these reported positive results on secondary outcomes (Tollefson et al, 1995). One of the three studies with a minimum inclusion age of 65 reported negative results (Evans et al, 1997), but this was in a population with significant medical comorbidity. It is difficult to draw any firm conclusions from these results. The studies reported here do not support that including younger (ie subjects aged 55–60 years) improves study outcomes. Given this, an inclusion age of 60 or older is reasonable for studies of geriatric depression although this must be balanced with the need to study large samples, which may be more difficult to achieve with higher minimum age requirements.

What about the upper end of the age range? There is no clear consensus about what age defines ‘elderly,’ although the over-85 age group has been referred to as ‘very old.’ A pooled analysis reported that advanced age does not appear to affect antidepressant response rates or time to remission (Gildengers et al, 2002). However, most of these placebo-controlled trials report a mean age in the 60s, although a few studies report mean ages in the 70s (Schweizer et al, 1998; Schneider et al, 2003) or 80s (Katz et al, 1990; Evans et al, 1997; Burrows et al, 2002). Both studies with samples who had a mean age in their 70s demonstrated a superiority of active agent over placebo, and also exhibited comparable response rates compared with other trials of drugs in their class (Tables 3 and 4).

Studies of populations with a mean age in the 80s showed a different pattern. Only one study found a difference between drug and placebo on primary and secondary outcomes (Katz et al, 1990). However, one cannot conclude that age alone resulted in the negative results seen in the other trials, as the populations in all three studies were medically ill and either hospitalized or living in nursing homes. This particular population is at high risk for depression, and research into safety and efficacy is urgently needed.

Study measures and antidepressant response rate

HAM-D is the most commonly used instrument in these trials to determine outcome, serving as the primary outcome for the majority of studies. Most studies reported a greater change in HAM-D score in the active over the placebo arm, with a few exceptions (Jarvik et al, 1982; Kane et al, 1983; Tollefson et al, 1995; Evans et al, 1997; Burrows et al, 2002). Of these negative studies, two included subjects aged 55 and over (Jarvik et al, 1982; Kane et al, 1983), one was in non-major depression (Burrows et al, 2002), and one was in medically ill subjects (Evans et al, 1997).

Although the two largest studies of SSRIs in elderly populations were considered to be positive trials (Tollefson et al, 1995; Schneider et al, 2003), neither demonstrated a robust difference in primary outcomes between treatment arms. The fluoxetine study (Tollefson et al, 1995) failed to find a significant difference in HAM-D change between groups, but found that fluoxetine subjects were significantly more likely to respond or remit based on final HAM-D scores (Table 4). The sertraline study (Schneider et al, 2003) detected a difference in HAM-D change; however, the mean adjusted difference between groups was only 1.5 points. Both trials demonstrated statistically significant but clinically unimpressive results on the percentage of subjects experiencing a 50% or greater remission on HAM-D (fluoxetine 44%; sertraline 35%; Table 4).

CGI was also commonly used, and most studies using it found that those subjects in the treatment arm were more likely to be rated as ‘improved’ (Table 4). CGI results typically followed the results of the HAM-D scale, although some studies found discrepancies in this correlation (Nair et al, 1995; Tollefson et al, 1995).

Other scales were used too sporadically to draw any firm conclusions. HAM-A found significantly greater improvement in the treatment group on two studies (Gerner et al, 1980; Branconnier et al, 1983). MADRS was used in only two studies (Tan et al, 1994; Halikas, 1995). Both reported negative results. The study by Tan et al had a small number of medically ill subjects and used a low-dose treatment strategy. The Halikas study found significant differences in MADRS score between arms at weeks 2 and 3, but not at study end point.

A review of these studies cannot make a definitive statement about using one scale over another in studies of geriatric depression. HAM-D has long been used as the ‘gold standard’ to assess antidepressant efficacy, and most of the studies reported here used this measure. Of note, there is some thought that unidimensional subscales of depressive symptoms derived from HAM-D may be more sensitive to antidepressant drug effects than is the composite HAM-D score (Entsuah et al, 2002). They may also be predictive of remission. Such an approach may not be able to differentiate between active agents, but may be useful in studies with placebo comparisons.

An additional challenge is how to define response in a way that is clinically meaningful. When using continuous rating scales such as HAM-D, a 50% reduction in score has often been used as an indicator of response (Frank et al, 1991). Unfortunately, many subjects with a 50% improvement remain highly symptomatic; this standard is not an acceptable characterization of response as residual or ‘subthreshold’ symptoms continue to have significant associated dysfunction and may increase the risk of developing further depressive episodes (Horwath et al, 1992; Judd et al, 1997; Maier et al, 1997; Van Londen et al, 1998). The persistence of residual symptoms in many subjects makes it an important outcome of treatment (Paykel et al, 1995; Van Londen et al, 1998; Nierenberg et al, 1999).

Absolute scores have been proposed to define remission: HAM-D scores ranging from 7 to 11 have previously been recommended (Nierenberg and Wright, 1999). Currently, an HAM-D score of 7 or less is currently viewed as a stringent criterion for complete remission (Ballinger, 1999). This secondary outcome may be a positive result in trials where measures of change do not differentiate active and placebo arms (Tollefson et al, 1995), and may be a means of separating subjects with true antidepressant response from those exhibiting nonspecific effects or spontaneous transient remission (Ballinger, 1999). It may also predict relapse, as subjects who achieve an HAM-D below 8 have a lower rate of relapse than did those subjects with greater residual symptoms (Paykel et al, 1995).

Could other scales be used? One alternative scale, MADRS, was ‘designed to be sensitive to change’ (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979), but its use is not as widespread as HAM-D. A recent retrospective study found that it was as sensitive an instrument as HAM-D for detecting antidepressant efficacy (Khan et al, 2002), but there is currently no compelling evidence that it is superior to HAM-D in geriatric populations. In fact, one study examining a small sample of elderly patients with Parkinson's disease concluded that HAMD-17 exhibited slightly better diagnostic performance than did MADRS (Leentjens et al, 2000).

It is important to remember that rating scales in current use are at least partially defined by prevailing diagnostic criteria for depression. Scales developed and validated for assessing major depression in general adult populations may not be appropriate to assess other depression diagnoses, such as minor or ‘subsyndromal’ depression. Moreover, as depression may have a different presentation or symptom constellation in older populations, scales developed or modified specifically for the geriatric population, such as the Geriatric Depression Scale or the Cornell Scale, may be more appropriate. This issue becomes even more important for trials examining depression in elderly patients with cognitive impairment, where dementia is a confounding issue.

Although measures of depression severity are the crucial outcome scales for antidepressant trials, other domains should also be assessed. There should be assessment of medical burden and disability, anxiety symptoms, and cognitive impairment, as these factors are all commonly comorbid with depression. Cognitive scales should also include measures of executive function, as deficits in executive function are often seen in late-life depression (Alexopoulos et al, 2000) and common scales such as the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein et al, 1975) do not adequately measure this domain.

Study duration

The studies included in this review had a wide range of durations, extending from 4 to 26 weeks (Table 1). Although a trial of 8 weeks may be necessary to declare nonresponse in younger populations (Quitkin et al, 2003), longer studies may be necessary to detect adequately improvement in the elderly population. For elderly populations, a 12-week trial would allow a sufficient time for clinical response in most of this patient population (Cohn et al, 1990), including very old subjects (Gildengers et al, 2002) and elderly patients with comorbid illness who may require longer to respond (Alexopoulos et al, 1996). However, extending trial duration may increase the risk of placebo response (Walsh et al, 2002).

Are shorter trials appropriate? There is some evidence to support the theory that subjects who respond to a given agent only minimally at 6 weeks will be unlike to show a significant response at 12 weeks (Roose and Sackeim, 2002). In such situations, it may be better for the individual if they are transitioned to another antidepressant agent.

Placebo Response Rate in Clinical Trials

Many of these studies have robust placebo responses (Tables 3 and 4); the placebo response rate in subjects with depression has been reported to be as high as 60–70% (Brown et al, 1988; Quitkin, 1999). Although many have questioned the continued need for placebo controls (Rothman and Michels, 1994), representatives from the scientific community (Charney, 2000; Schatzberg and Kraemer, 2000; Kupfer and Frank, 2002; Walsh et al, 2002), the National Institute of Mental Health (Hyman and Shore, 2000), and mental health consumers (Charney et al, 2002) have acknowledged that placebo-controlled trials continue to be necessary for the appropriate evaluation of new agents for the treatment of mood disorders. They also concur that such need should be balanced with appropriate safeguards to provide protection and benefit to study participants.

Placebo response rates are variable across antidepressant trials (Quitkin, 1999; Walsh et al, 2002), and may occur for a variety of reasons. As discussed by Schatzberg and Kraemer (2000), these may include trial design flaws, rater bias at assessment of baseline symptom favoring enrollment over exclusion, spontaneous remission, or other pretreatment characteristics of individual subjects.

The response rate to placebo has increased over the last 20 years (Walsh et al, 2002). Multiple issues may contribute to this change, including shifting characteristics of study participants or change in recruitment practices from primarily referral to advertisement-based recruitment. Even length of the trial may contribute, as the proportion of patients responding to placebo increases with trial length (Khan et al, 2000; Walsh et al, 2002). Although some have proposed the main reason for this shift is a change in participant characteristics (Walsh et al, 2002), others have observed that remission rates may vary substantially across sites in a multicenter trial (Small et al, 1999), and so propose that differences between participating sites also contribute to this change and variability (Schneider and Small, 2002).

Does trial length contribute to the placebo response in the elderly population? Examining shorter studies of 4–5 weeks duration, one (Kane et al, 1983) of six studies failed to demonstrate a differential change on HAM-D (Table 3); a comparable result is seen in studies of 7–8 weeks duration, where one (Evans et al, 1997) of five studies did not demonstrate a significant difference. The one study of 6 weeks duration (Tollefson et al, 1995) did not demonstrate a difference in HAM-D change between groups. There was also significant overlap between the placebo response rate between shorter and longer trials for the secondary outcomes of CGI and HAM-D measures of remission and response.

What about other study design elements intended to reduce placebo response? Many but not all of the studies included here had a washout period or a 1-week placebo lead-in period. A single-blind placebo lead-in period is used in an attempt to minimize placebo response, which arguably one may say can be successful (Tollefson et al, 1995), although some have proposed that it provides no advantage in acute-phase efficacy trials (Triveldi and Rush, 1994). Some have suggested alternatives, including a variable length, double-blind placebo lead-in period, which may allow for improved prerandomization detection of placebo responders (Faries et al, 2001).

There are other means to minimize the placebo response. These range from recommended adjustments to clinical trial design (Schatzberg and Kraemer, 2000) to new randomization techniques, such as adaptive allocation designs (Krishnan, 2000). These techniques must be evaluated in terms of safety to subjects, how these designs influence placebo response rates, and cost.

Limitations of this Review

Any review of clinical trials that relies on published reports is subject to publication bias, as trials reporting positive results are more likely to be published than negative trials. This is a difficult issue to resolve, as unpublished data have not undergone a rigorous peer-review process; however, the absence of peer review does not necessarily negate the validity of the results of that study. This bias likely has an effect on our conclusions as there have been unpublished antidepressant trials in the elderly that failed to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between medication and placebo. Had these trials been published and available, our conclusions may have been different.

There are other limitations. We did not perform a meta-analysis of study data, which limits our ability to draw firm conclusions. Moreover, the generalizability of our NNT analysis is limited due to the small number of agents studied. Additionally, the numbers of subjects participating in SSRI trials was so much larger than those participating in trials of other agents, that differences between antidepressant classes may exist that could not be detected in this analysis. Finally, it is possible that trials were missed. The two major databases we searched are not comprehensive regarding clinical trials; however, this was supplemented by reviewing references from a variety of sources. Our report is further limited by excluding trials that included subjects with cognitive impairment, such as a placebo-controlled study of citalopram in elderly depressed subjects with and without dementia (Nyth et al, 1992).

CONCLUSIONS

Based on published reports, antidepressants appear to be effective in treating depression in elderly individuals, but it is unclear how results from trials of patients without significant comorbidity can be generalized to many clinical populations. Additionally, the largest trials conducted to date demonstrate a significant placebo response rate and a significant number of subjects who do not respond or have residual depressive symptoms. Moreover, evidence supporting the use of commonly used agents such as venlafaxine, bupropion, and escitalopram is lacking. Research is required to investigate possible pretreatment characteristics that may contribute to higher placebo responses and to investigate alternative trial designs. Appropriate trial design may minimize, but likely not eliminate, the risk of significant placebo response. Development of newer, more effective agents is still necessary, along with studies examining the utility of augmentation strategies. Inclusion of broader samples as used in effectiveness studies may additionally increase the generalizability of study results.

Studies of depression in elderly populations present specific challenges. As medical comorbidity may affect response to antidepressant treatment, measures need to be included in trials to account for this confounder. Psychosocial stressors specific to this population should also be considered. These may contribute to poor response rates. Unfortunately, there are very few published well-designed placebo-controlled trials in the elderly. This is a significant limitation to the clinical care of this population, particularly as there is no strong evidence supporting the use of many commonly used antidepressants in this population.

We recommend that studies of geriatric populations be in age groups 60 and older. It is unclear that a placebo lead-in period provides any benefit in terms of reducing placebo response, but other approaches to reducing this response rate have been proposed. Research is needed to examine the optimal trial length for geriatric depression. Other trial design alterations, such as limiting the number of treatment arms, are also critical. Clearly, further work is needed in clinical trial design to enable more sensitive detection of antidepressant response.

References

Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Feder M, Einhorn A et al (1996). Recovery in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 305–312.

Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kalayam B, Kakuma T, Gabrielle M et al (2000). Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 285–290.

Ballinger JC (1999). Clinical guidelines for establishing remission in patients with depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 60 (Suppl 22): 29–34.

Branconnier RJ, Cole JO, Ghazvinian S, Rosenthal S (1982). Treating the depressed elderly patient: the comparative behavioral pharmacology of mianserin and amitriptyline. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol 32: 195–212.

Branconnier RJ, Cole JO, Ghazvinian S, Spera KF, Oxenkrug GF, Bass JL (1983). Clinical pharmacology of bupropion and imipramine in elderly depressives. J Clin Psychiatry 44: 130–133.

Brown WA, Dornseif BE, Wernicke JF (1988). Placebo response in depression: a search for predictors. Psychiatry Res 26: 259–264.

Burrows AB, Salzman C, Satlin A, Noble K, Pollock BG, Gersh T (2002). A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine in nursing home residents with non-major depression. Depress Anxiety 15: 102–110.

Caine ED, Lyness JM, King DA (1993). Reconsidering depression in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1: 4–20.

Charney DS (2000). The use of placebos in randomized clinical trials of mood disorders: well justified, but improvements in design are indicated. Biol Psychiatry 47: 687–688.

Charney DS, Nemeroff CB, Lewis L, Laden SK, Gorman JM, Laska EM et al (2002). National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the use of placebo in clinical trials of mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59: 262–270.

Cohn CK, Shrivastava R, Mendels J, Cohn JB, Fabre LF, Claghorn JL et al (1990). Double-blind, multicenter comparison of sertraline and amitriptyline in elderly depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 51(Suppl B): 28–33.

Cohn JB, Varga L, Lyford A (1984). A two-center double-blind study of nomifensine, imipramine, and placebo in depressed geriatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 45: 68–72.

Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry 52: 193–204.

Cook RJ, Sackett DL (1995). The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 310: 452–454.

de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM (2003). How to measure comorbidity: a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol 56: 221–229.

Entsuah R, Shaffer M, Zhang J (2002). A critical examination of the sensitivity of unidimensional subscales derived from the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale to antidepressant drug effects. J Psychiatr Res 36: 437–448.

Evans M, Hammond M, Wilson K, Lye M, Copeland J (1997). Placebo-controlled treatment trial of depression in elderly physically ill patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 12: 817–824.

Faries DE, Heiligenstein JH, Tollefson GD, Potter WZ (2001). The double-blind variable placebo lead-in period: results from two antidepressant clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21: 561–568.

Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA et al (2003). Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin N Am 26: 457–494.

Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RAJ, Winokur G, Munoz R (1972). Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 26: 57–63.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975). ‘Mini-mental state’ a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198.

Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW et al (1991). Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 851–855.

Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M (1993). Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA 270: 1819–1825.

Gasto C, Navarro V, Marcos T, Portella MJ, Torra M, Rodamilans M (2003). Single-blind comparison of venlafaxine and nortriptyline in elderly major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23: 21–26.

Georgotas A, McCue RE, Friedman E, Cooper TB (1987). Response of depressive symptoms to nortriptyline, phenelzine, and placebo. Br J Psychiatry 151: 102–106.

Gerner R, Estabrook W, Steuer J, Jarvik L (1980). Treatment of geriatric depression with trazodone, imipramine, and placebo: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 41: 216–220.

Gerson S, Belin TR, Kaufman A, Mintz J, Jarvik L (1999). Pharmacological and psychological treatments for depressed older patients: a meta-analysis and overview of recent findings. Harvard Rev Psychiatry 7: 1–28.

Gildengers AG, Houck PR, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Mazumdar S, Miller MD et al (2002). Course and rate of antidepressant response in the very old. J Affect Disord 69: 177–184.

Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT et al (2002). Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA 288: 701–709.

Guy W (1976). Clinical global impressions. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. National Institute of Mental Health, pp 217–222.

Halikas JA (1995). Org 3770 (mirtazapine) versus trazodone: a placebo controlled trial in depressed elderly patients. Hum Psychopharmacol 10(Suppl 2): S125–S133.

Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23: 56–62.

Horwath E, Johnson J, Klerman GL, Weissman MM (1992). Depressive symptoms as relative and attributable risk factors for first-onset major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49: 817–823.

Hoyberg OJ, Maragakis B, Mullin J, Norum D, Stordall E, Ekdahl P et al (1996). A double-blind multicentre comparison of mirtazapine and amitriptyline in elderly depressed patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 93: 184–190.

Hyman SE, Shore D (2000). A NIMH perspective on the use of placebos. Biol Psychiatry 47: 689–691.

Jansen W, Siegried K (1984). Nomifensine in geriatric inpatients: a placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 45: 63–67.

Jarvik LF, Mintz J, Steuer J, Gerner R (1982). Treating geriatric depression: a 26-week interim analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 30: 713–717.

Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS et al (2001). Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med 161: 1849–1856.

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Paulus MP (1997). The role and clinical significance of subsyndromal depressive symptoms (SSD) in unipolar major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 45: 5–18.

Kane JM, Cole K, Sarantakos S, Howard A, Borenstein M (1983). Safety and efficacy of bupropion in elderly patients: preliminary observations. J Clin Psychiatry 44: 134–136.

Karlsson I, Godderis J, Lima CAM, Nygaard H, Simanyi M, Taal M et al (2000). A randomised, double-blind comparison of the efficacy and safety of citalopram compared to mianserin in elderly, depressed patients with or without mild to moderate dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15: 295–305.

Katon W, Schulberg H (1992). Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 14: 237–247.

Katz IR, Parmelee PA, Streim JE (1995). Depression in older patients in residential care: significance of dysphoria a dimensional assessment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 3: 161–169.

Katz IR, Reynolds CF, Alexopoulos GS, Hackett D (2002). Venlafaxine ER as a treatment for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: pooled analysis of five randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 50: 18–25.

Katz IR, Simpson GM, Curlik SM, Parmelee PA, Muhly C (1990). Pharmacologic treatment of major depression for elderly patients in residential care settings. J Clin Psychiatry 51: 41–48.

Khan A, Khan SR, Shankles EB, Polissar NL (2002). Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery–Asburg depression rating scale, the Hamilton depression rating scale, and the clinical global impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 17: 281–285.

Khan A, Warner HA, Brown WA (2000). Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 311–317.

Koppel J, Greenwald BS, Kramer E, Kremen N (2003). Critical review of antidepressant trials in late-life depression. International Psychogeriatric Association, 11th Congress. Chicago, IL, USA.

Krishnan KRR (2000). Efficient trial designs to reduce placebo requirements. Biol Psychiatry 47: 724–726.

Krishnan KRR, Hays JC, Blazer DG (1997). MRI-defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 154: 497–501.

Kupfer DJ, Frank E (2002). Placebo in clinical trials for depression: complexity and necessity. JAMA 287: 1853–1854.

Lasser RA, Sunderland T (1998). Newer psychotropic use in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 46: 202–207.

Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, Reynolds CF, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML et al (1997). Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA 278: 1186–1190.

Leentjens AGF, Verhey FRJ, Lousberg R, Spitsbergen H, Wilmink FW (2000). The validity of the Hamilton and Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scales as screening and diagnostic tools for depression in Parkinson's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15: 644–649.

Mahapatra SN, Hackett DN (1997). A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group comparison of venlafaxine and dothiepin in geriatric patients with major depression. Int J Clin Pract 51: 209–213.

Maier W, Gansicke M, Weiffenbach O (1997). The relationship between major and subthreshold variants of unipolar depression. J Affect Disord 45: 41–51.

Merideth CH, Feighner JP, Hendrickson G (1984). A double-blind comparative evaluation of the efficacy and safety of nomifensine, imipramine, and placebo in depressed geriatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 45: 73–77.

Mittmann N, Herrmann N, Einarson TR, Busto UE, Lanctot KL, Liu BA et al (1997). The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants in late life depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 46: 191–217.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134: 382–389.

Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds III CF, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D et al (2001). Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16: 585–592.

Nair NPV, Amin M, Holm P, Katona C, Klitgaard N, Ng Ying Kin NMK et al (1995). Moclobemide and nortriptyline in elderly depressed patients. A randomized, multicentre trial against placebo. J Affect Disord 33: 1–9.

Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL, Evans DL (1998). Depression and cardiac disease. Depress Anxiety 8 (Suppl 1): 71–79.

Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, Alpert JE, Pava JA, Worthington JJ et al (1999). Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 60: 221–225.

Nierenberg AA, Wright EC (1999). Evolution of remission as the new standard in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 60 (Suppl 22): 7–11.

Nyth AL, Gottfries CG, Lyby K, Smedegaard-Andersen L, Gylding-Sabroe J, Kristensen M et al (1992). A controlled multicenter clinical study of citalopram and placebo in elderly depressed patients with and without concomitant dementia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 86: 138–145.

Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD (2002a). Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 129–141.

Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS, Breitner JC et al (2002b). Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 125–128.

Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A (1995). Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med 25: 1171–1180.

Quitkin FM (1999). Placebos, drug effects, and study design: a clinician's guide. Am J Psychiatry 156: 829–836.

Quitkin FM, Petkova E, McGrath PJ, Taylor B, Beasley C, Stewart J et al (2003). When should a trial of fluoxetine for major depression be declared failed? Am J Psychiatry 160: 734–740.

Reynolds CF, Lebowitz BD, Schneider LS (1993). The NIH Consensus Development Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life: an overview. Psychopharmacol Bull 29: 83–85.

Roose SP, Sackeim HA (2002). Clinical trials in late-life depression: revisited. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 503–505.

Rothera I, Jones R, Gordon C (2002). An examination of the attitudes and practice of general practitioners in the diagnosis and treatment of depression in older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17: 354–358.

Rothman KJ, Michels KB (1994). The continuing unethical use of placebo controls. N Engl J Med 331: 394–398.

Rovner BW, German PS, Brant LJ, Clark R, Burton L, Folstein MF (1991). Depression and mortality in nursing homes. JAMA 265: 993–996.

Rush AJ, Trivedi M, Fava M (2003). Depression, IV: STAR*D treatment trial for depression. Am J Psychiatry 160: 237.

Saiz-Ruiz J, Ibanez A, Diaz-Marsa M, Arias F, Carrasco JL, Huertas D et al (2002). Nefazodone in the treatment of elderly patients with depressive disorders: a prospective, observational study. CNS Drugs 16: 635–643.

Schatzberg AF, Kraemer HC (2000). Use of placebo control groups in evaluating efficacy of treatment of unipolar major depression. Biol Psychiatry 47: 736–744.

Schatzberg AF, Kremer C, Rodrigues HE, Murphy GM, Group TMvPS (2002). Double-blind, randomized comparison of mirtazapine and paroxetine in elderly depressed patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 541–550.

Schneider LS, Nelson JC, Clary CM, Newhouse P, Krishnan KRR, Shiovitz T et al (2003). An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry 160: 1277–1285.

Schneider LS, Small GW (2002). The increasing power of placebos in trials of antidepressants. JAMA 288: 450.

Schweizer E, Rickels K, Hassman H, Garcia-Espana F (1998). Buspirone and imipramine for the treatment of major depression in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry 59: 175–183.

Small GW, Schneider LS, Hamilton SH, Bystritsky A, Meyers BS, Nemeroff CB (1999). Site variability in a multisite geriatric depression trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 11: 1089–1095.

Smeraldi E, Rizzo F, Crespi G (1998). Double-blind, randomized study of venlafaxine, clomipramine, and trazodone in geriatric patients with major depression. Primary Care Psychiatry 4: 189–195.

Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robinson E (1977). Research Diagnostic Criteria for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd edn. Biomedical Research Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York.

Tan RSH, Barlow RJ, Abel C, Reddy S, Palmer AJ, Fletcher AE et al (1994). The effect of low dose lofempramine in depressed elderly patients in general medical wards. Br J Psychiatry 37: 321–324.

Thomas L, Mulsant BH, Solano FX, Black AM, Bensasi S, Flynn T et al (2002). Response speed and rate of remission in primary and specialty care of elderly patients with depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 583–591.

Tollefson GD, Bosomworth JC, Heiligenstein JH, Potvin JH, Holman S (1995). A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine in geriatric patients with major depression. The Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group. Int Psychogeriatr 7: 89–104.

Triveldi M, Rush J (1994). Does a placebo run-in or a placebo treatment cell affect the efficacy of antidepressant medications? Neuropsychopharmacology 11: 33–43.

Van Londen L, Molenaar RPG, Goekoop JG, Zwinderman AH, Rooijmans HGM (1998). Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychol Med 28: 731–735.

Wakelin JS (1986). Fluvoxamine in the treatment of the older depressed patient; double-blind, placebo-controlled data. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1: 221–230.

Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M (2002). Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA 287: 1840–1847.

Weihs KL, Settle EC, Batey SR, Houser TL, Donahue RM, Ascher JA (2000). Bupropion sustained release versus paroxetine in the treatment of depression in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry 61: 196–202.

Wilson K, Mottram P, Sivanranthan A, Nightingale A (2001). Antidepressants versus placebo for the depressed elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD000561 (August 2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, NIMH Grants R01 MH062158 and K23 MH65939, and a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

POSSIBLE CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr Taylor has received honoraria from Pfizer. He has also served as a speaker for Janssen Pharmaceutica, LP. He does not own stock in these companies. Dr Doraiswamy has received grants and consulting or speaking fees from Wyeth, Pfizer, GSK, Forest, Lilly, and Organon. He does not own stock in these companies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, W., Doraiswamy, P. A Systematic Review of Antidepressant Placebo-Controlled Trials for Geriatric Depression: Limitations of Current Data and Directions for the Future. Neuropsychopharmacol 29, 2285–2299 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300550

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300550

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Antidepressants in nursing homes for dependent older patients: the cross-sectional associations of institutional factors with prescription conformance

European Geriatric Medicine (2019)

-

The Pharmacology and Clinical Use of the Antidepressants Vilazodone, Levomilnacipran, and Vortioxetine for Depression in the Elderly

Current Geriatrics Reports (2015)

-

Unmet needs and research challenges for late-life mood disorders

Aging Clinical and Experimental Research (2014)

-

Course and outcomes of depression in the elderly

Current Psychiatry Reports (2006)