Abstract

Molecules are expected to be promising information devices1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Theoretical proposals have been made for logic gates with a molecular wave packet modulated by a strong femtosecond laser pulse9,10,11,12,13,14,15. However, it has not yet been observed how this changes the population of each eigenstate within the wave packet. Here we demonstrate direct observation of the population beating clearly as a function of the delay of the strong laser pulse. The period is close to the recurrence period of the wave packet, even though a single eigenstate should have no information on the wave-packet motion. This unusual beat arises from quantum interference among multiple eigenstates combined on a single eigenstate. This new concept, which we refer to as ‘strong-laser-induced interference’, is not specific to molecular eigenstates, but universal to the superposition of any eigenstates in a variety of quantum systems, being a new tool for quantum logic gates, and providing a new method to manipulate wave packets with femtosecond laser pulses in general applications of coherent control16,17,18,19,20.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The wavefunctions of electrically neutral systems can replace electric charges of the present Si-based circuits, whose further downsizing will soon reach its limit where current leakage will cause heat and errors with insulators thinned to atomic levels21. Atoms and molecules are promising candidates for these neutral systems, in which the population and phase of each eigenstate serve as carriers of information1,2,22,23. A shaped ultrashort laser pulse can access many eigenstates simultaneously within a single atom or molecule, manipulating the amplitude and phase of each eigenstate individually to write more than one million distinct binary codes in the angstrom space1,2. Molecules in particular are now expected to be promising components to develop scalable quantum computers5,6,7,8. The development of I/O and logic gates with molecules should be meaningful for us to be prepared for such a future scalable system. It is therefore important to study information processing with molecular eigenstates for both high-density classical information processing and quantum information processing. This background has motivated us to propose molecular eigenstate-based information processing (MEIP), and to demonstrate the ultrafast Fourier transform based on the temporal evolution of a molecular wave packet2,3,4. For more universal computing in MEIP, however, one should consider another class of logic gates with a strong femtosecond laser pulse whose broad bandwidth and high intensity allow for multiple transitions among different eigenstates within a wave packet simultaneously. This scheme has been employed in a number of theoretical studies on MEIP logic gates9,10,11,12,13,14,15, and also in a few experimental studies24, but it has not yet been observed experimentally how each eigenstate changes its population with those multiple transitions within a wave packet. Here, we report the direct observation of the population of each vibrational eigenstate within a wave packet modulated by a strong non-resonant femtosecond laser pulse in the near-infrared (NIR) region.

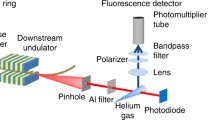

Figure 1 shows a scheme of our experiment. The I2 molecules were prepared in the electronic ground state (X1Σg+) by an expansion of a heated I2/Ar mixture into a vacuum chamber through a pulsed nozzle (Parker Hannifin, General Valve model 009-0506-900) driven at a repetition rate of 40 Hz. Vibrational and rotational temperatures of the I2 molecules were not measured in the present experiment, but the sample conditions were almost identical to those of our previous study25.

The output of a Ti:sapphire laser system (Quantronix; Titan, pulse width ∼100 fs, repetition rate 1 kHz) was used to pump two optical parametric amplifiers (Quantronix; TOPAS) to generate pump and NIR pulses tuned around 540 nm and 1,400 nm, respectively.

The pump and NIR pulses were introduced collinearly into the vacuum chamber through a plano-convex lens (f=250 mm) to intersect the molecular jet at ∼5 mm downstream of the nozzle end. The pump pulse was used to create a vibrational wave packet composed of the vibrational eigenstates around vB=28 of the B electronic state of the I2 molecule, and that wave packet was irradiated with the NIR pulse (∼50 μJ per pulse). The pump–NIRdelay τNIR was tuned with a mechanical stage in the optical path of the NIR pulse. The origin of the delay τNIR=0 was determined by a cross-correlation measurement based on sum-frequency generation.

We employed a narrow-band nanosecond probe pulse prepared with a XeCl-excimer pumped dye laser (Lambda Physik; COMPex 110 and SCANmate 2E, Exciton; Exalite 398). This narrow-band interrogation allowed us to measure the population of each eigenstate within the wave packet individually. The probe pulse was introduced collinearly with the pump and NIR pulses, delayed from the pump pulse by ∼35 ns, and used for the population measurement of each vibrational eigenstate within the wave packet by the laser-induced fluorescence technique, with the E state being the fluorescent state. The fluorescence was measured with a photomultiplier attached to the exit slit of a monochromator. The outputs of the photomultiplier were amplified with a preamplifier and input to a gated integrator, whose outputs were fed into a computer and averaged over 40 probe laser shots at each τNIR.

Figure 2 shows the populations of the eigenstates vB=25, 27 and 29 measured with the probe wavelength tuned to the E–B vibronic bands vE − vB=20–25, 21–27 and 23–29, respectively, and plotted as functions of the NIR delay τNIR. The population of each eigenstate increases and decreases alternately, showing a clear beat, referred to as an NIR beat hereafter, and its period is nearly equal to the recurrence period h/ΔE of the wave packet, with ΔE being the energy spacing between adjacent vibrational levels. It is reasonably considered that each eigenstate within a wave packet does not have any information on the position and motion of the wave packet, so that a beat should appear only when the superposition of two or more eigenstates is observed without distinguishing individual eigenstates. However, the present beat shown in Fig. 2 appears even when a single eigenstate is selectively observed. Figure 2 also shows that the NIR beats are phase-shifted among different eigenstates (see the vertical dashed line in Fig. 2), and this allows for active control of the relative populations of different vibrational eigenstates within a wave packet, which is referred to as a population code in MEIP (refs 1, 2, 25), by tuning the NIR delay τNIR. We made another series of measurements for vB=27 in which the beat amplitude (the difference between the top and bottom) increased almost linearly as we increased the power density of the NIR pulse from ∼0.4 to ∼1.6 TW cm−2;∼1 TW cm−2 gave the amplitude around 30% of the population prepared by the pump pulse.

NIR beats observed in the populations of the eigenstates vB=25, 27 and 29 as functions of the pump–NIR delay τNIR. Each trace is an average of three repeated scans. The vertical scalings of the traces for vB=25, 27 and 29 have been normalized by their intensities averaged over τNIR=−536∼−283,−531∼−278 and −535∼−281 fs, respectively.

Figure 3a shows the NIR beat of vB=25 on a longer timescale. This beat observed in a single eigenstate shows an unexpected feature similar to the collapse and revival of a wave packet, which should be seen only when three or more eigenstates are superposed on an anharmonic potential curve26,27. The Fourier transform of this NIR beat is shown in Fig. 3b, demonstrating that the beat contains at least three different frequencies assigned to the energy separations of the eigenstates vB=26, 27 and 28 from vB=25, respectively28.

a, Collapse and revival of the NIR beat observed in the population of the eigenstate vB=25 as a function of the pump–NIR delay τNIR scanned for a longer period than that of Fig. 2. The trace is an average of two repeated scans. The vertical scaling of the trace has been normalized by its intensity averaged over τNIR=−698∼−445 fs. b, Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the NIR beat in a with τNIR=636 fs∼15.31 ps with zero padding. The Hanning function has been used as a window function.

To understand this unusual beat and its collapse and revival, it is helpful to consider the interference among multiple quantum mechanical pathways leading to a common final state. Figure 4 schematically shows this multipath interference. Starting from a common initial state |i〉, there could be multiple pathways to the state |n〉 indicated by red, black and blue solid lines in this example. Namely, they are (1) |i〉→|n〉→|n〉 (black); and (2) |i〉→|n±1〉→|n〉 (red and blue). The states |n〉 and |n±1〉 oscillate with periods of around 1.8 fs, but those periods slightly differ from each other. Accordingly the relative phases between |n〉 and |n±1〉 develop from 0 to 2π synchronously with a periodical recurrence motion of the wave packet composed of these states25, so that the constructive and destructive interferences alternately appear with a period close to the recurrence period of the wave packet, giving the beat seen in Fig. 2. Owing to the potential anharmonicity, however, this beat shows collapse and revival as seen in Fig. 3. The latter halves of pathways (1) and (2) are referred to as Rayleigh scattering and impulsive stimulated Raman scattering, respectively. Figure 3 clearly shows that the main components of the beat seen in vB=25 are the interferences between vB=25 and other states. It is thus reasonably understood from this result that the present unusual beat and its collapse and revival arise from the interferences between Rayleigh scattering and Raman scatterings, as shown in Fig. 4. It is interesting to note that this interference does not occur on the scattered light, but occurs only on the quantum states of matter resulting from those Rayleigh and Raman scatterings. We did not address the phase shifts during those scatterings in the above discussion. The amounts of such phase shifts, which are indicated as δn and δn±1 in Fig. 4, do not depend on τNIR, but depend on the characteristics of the NIR pulse, such as its phase spectrum29. The mathematical formulation of this multipath interference is given in the Supplementary Information.

Starting from a common initial state |i〉, there are multiple pathways |i〉→|n−1〉→|n〉, |i〉 →|n〉→|n〉 and |i〉→|n+1〉→ |n〉, indicated by red, black and blue solid lines, respectively, to the common final state |n〉. Those multiple pathways interfere with each other. The amounts of phase shifts during the NIR pulse are indicated as δn−1,δn and δn+1. See text for further details.

The unusual beat and its collapse and revival that we have observed in a single eigenstate are thus elucidated in terms of quantum interference induced by the non-resonant NIR pulse among multiple eigenstates optically combined on a single eigenstate, as schematically shown in Fig. 4. It is important to note that the coherence among those eigenstates is preserved during this state mixing. As the relative phase among the eigenstates changes synchronously with the periodic motion of the wave packet, the interference can be controlled by tuning the timing of the NIR pulse, so that the amplitude and phase of each eigenstate can be manipulated. Moreover the relative phase among the combined eigenstates should be sensitive also to the phase spectrum of the NIR pulse29. Chirping the pulse, therefore, should provide another degree of control30. This new concept, which we refer to as ‘strong-laser-induced interference (SLI)’, is a new resource to develop the logic gates in MEIP, and provides a new method to manipulate wave packets with strong femtosecond laser pulses in general applications of coherent control, such as chemical reaction control16,17,18,19,20. Importantly, SLI is not specific to the vibrational eigenstates of a molecule, but universal to the superposition of any eigenstates in a variety of quantum systems.

References

Ohmori, K. Wave-packet and coherent control dynamics. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 60, 487–511 (2009).

Hosaka, K. et al. Ultrafast Fourier transform with a femtosecond-laser-driven molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 180501 (2010).

Walmsley, I. Ultrafast computing with molecules. Physics 3, 38 (2010).

Hand, E. Leak-proof chips. Nature 465, 138–139 (2010).

DeMille, D. Quantum computation with trapped polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 067901 (2002).

Micheli, A., Brennen, G. K. & Zoller, P. A toolbox for lattice-spin models with polar molecules. Nature Phys. 2, 341–347 (2006).

André, A. et al. A coherent all-electrical interface between polar molecules and mesoscopic superconducting resonators. Nature Phys. 2, 636–642 (2006).

Shuman, E. S., Barry, J. F. & DeMille, D. Laser cooling of a diatomic molecule. Nature 467, 820–823 (2010).

Palao, J. P. & Kosloff, R. Quantum computing by an optimal control algorithm for unitary transformations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 188301 (2002).

Palao, J. P. & Kosloff, R. Optimal control theory for unitary transformations. Phys. Rev. A 68, 062308 (2002).

Tesch, C. M. & de Vivie-Riedle, R. Quantum computation with vibrationally excited molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 175901 (2002).

de Vivie-Riedle, R. & Troppmann, U. Femtosecond lasers for quantum information technology. Chem. Rev. 107, 5082–5100 (2007).

Ohtsuki, Y. Simulating the Deutsch–Jozsa algorithm using vibrational states of I2 excited by optimally designed gate pulses. Chem. Phys. Lett. 404, 126–131 (2005).

Bihary, Z., Glenn, D. R., Lidar, D. A. & Apkarian, V. A. An implementation of the Deutsch–Jozsa algorithm on molecular vibronic coherences through four-wave mixing: A theoretical study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 360, 459–465 (2002).

Menzel-Jones, C. & Shapiro, M. Robust operation of a universal set of logic gates for quantum computation using adiabatic population transfer between molecular levels. Phys. Rev. A 75, 052308 (2007).

Sussman, B. J., Townsend, D., Ivanov, M. Y. & Stolow, A. Dynamic Stark control of photochemical processes. Science 314, 278–281 (2006).

Bruner, B. D., Suchowski, H., Vitanov, N. V. & Silberberg, Y. Strong-field spatiotemporal ultrafast coherent control in three-level atoms. Phys. Rev. A 81, 063410 (2010).

Levy, I., Shapiro, M. & Brumer, P. Two-pulse coherent control of electronic states in the photodissociation of IBr: Theory and proposed experiment. J. Chem. Phys. 93, 2493–2498 (1990).

Markevitch, A. N., Romanov, D. A., Smith, S. M. & Levis, R. J. Rapid proton transfer mediated by a strong laser field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 163002 (2006).

Bustard, P. J., Sussman, B. J. & Walmsley, I. A. Amplification of impulsively excited molecular rotational coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 193902 (2010).

Lundstrom, M. Moore’s law forever? Science 299, 210–211 (2003).

Ahn, J., Rangan, C., Hutchinson, D. N. & Bucksbaum, P. H. Quantum-state information retrieval in a Rydberg-atom data register. Phys. Rev. A 66, 022312 (2002).

Gilowski, M. et al. Gauss sum factorization with cold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 030201 (2008).

Amitay, Z., Kosloff, R. & Leone, S. R. Experimental coherent computation of a multiple-input AND gate using pure molecular superpositions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 359, 8–14 (2002).

Katsuki, H., Hosaka, K., Chiba, H. & Ohmori, K. Read and write amplitude and phase information by using high-precision molecular wave-packet interferometry. Phys. Rev. A 76, 031403 (2007).

Averbukh, I. S. & Perelman, N. F. Fractional revivals—universality in the long-term evolution of quantum wave-packets beyond the correspondence principle dynamics. Phys. Lett. A 139, 449–453 (1989).

Katsuki, H., Chiba, H., Girard, B., Meier, C. & Ohmori, K. Visualizing picometric quantum ripples of ultrafast wave-packet interference. Science 311, 1589–1592 (2006).

Luc, P. Molecular constants and Dunham expansion parameters describing the B–X system of the iodine molecule. J. Mol. Spec. 80, 41–55 (1980).

Polack, T., Oron, D. & Silberberg, Y. Control and measurement of a non-resonant Raman wavepacket using a single ultrafast pulse. Chem. Phys. 318, 163–169 (2005).

Merkel, W. et al. Chirping a two-photon transition in a multistate ladder. Phys. Rev. A 76, 023417 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Fruitful discussions with M. Shapiro, M. G. Raymer, R. J. Levis, D. A. Romanov, S. M. Smith, J. J. Brady, N. Takei, A. Hishikawa, J. Doyle and D. DeMille are greatly acknowledged. This work was partly supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research by JSPS and Photon-Frontier-Consortium Project by MEXT of Japan. H.I. thanks JSPS and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K. and K.O. designed the experiment. H.K., H.C. and K.O. constructed the apparatus. H.G., H.K. and H.I. carried out the measurements. H.G., H.K. and K.O. analysed data. H.G. and K.O. prepared the manuscript, which was polished by all authors. K.O. conceived and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 241 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goto, H., Katsuki, H., Ibrahim, H. et al. Strong-laser-induced quantum interference. Nature Phys 7, 383–385 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1960

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1960

This article is cited by

-

Optical preparation and manipulation of ground-state coherent vibrational wavepackets of varying constituents in \(\hbox {HD}^{+}\)

Pramana (2019)

-

Optically Engineered Quantum States in Ultrafast and Ultracold Systems

Foundations of Physics (2014)

-

Our choice from the recent literature

Nature Photonics (2011)

-

Wave packets get a kick

Nature Physics (2011)