Abstract

Glasses are dynamically arrested states of matter that do not exhibit the long-range periodic structure of crystals1,2,3,4. Here we develop new insights from theory and simulation into the impact of quantum fluctuations on glass formation. As intuition may suggest, we observe that large quantum fluctuations serve to inhibit glass formation as tunnelling and zero-point energy allow particles to traverse barriers facilitating movement. However, as the classical limit is approached a regime is observed in which quantum effects slow down relaxation making the quantum system more glassy than the classical system. This dynamical ‘reentrance’ occurs in the absence of obvious structural changes and has no counterpart in the phenomenology of classical glass-forming systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although a wide variety of glassy systems ranging from metallic to colloidal can be accurately described using classical theory, quantum systems ranging from molecular, to electronic and magnetic form glassy states5,6. Perhaps the most intriguing of these is the coexistence of superfluidity and dynamical arrest, namely the ‘superglass’ state suggested by recent numerical, theoretical and experimental work7,8,9. Although such intriguing examples exist, at present there is no unifying framework to treat the interplay between quantum and glassy fluctuations in the liquid state.

To attempt to formulate a theory for a quantum liquid to glass transition, we may first appeal to the classical case for guidance. Here, a microscopic theory exists in the form of mode-coupling theory (MCT), which requires only simple static structural information as input and produces a full range of dynamical predictions for time correlation functions associated with single-particle and collective fluctuations10. Although MCT has a propensity to overestimate a liquid’s tendency to form a glass, it has been shown to account for the emergence of the non-trivial growing dynamical length scales associated with vitrification11. Perhaps more importantly, MCT has made numerous non-trivial predictions ranging from logarithmic temporal decay of density fluctuations and reentrant dynamics in adhesive colloidal systems to various predictions concerning the effect of compositional mixing on glassy behaviour12,13. These have been confirmed by both simulation and experiment14,15,16.

A fully microscopic quantum version of MCT (QMCT) that requires only the observable static structure factor as input may be developed along the same lines as the classical version. Indeed, a zero-temperature version of such a theory has been developed and successfully describes the wave-vector-dependent dispersion in superfluid helium17. In the Supplementary Information, we outline the derivation of a full temperature-dependent QMCT. In the limit of high temperatures, our theory reduces to the well-established classical MCT, whereas at zero temperature it reduces precisely to the aforementioned T=0 quantum theory. The structure of these two theories is markedly different, suggesting the possibility of non-trivial emergent physics over the full range of parameters that tune between the classical and quantum limits. Although this formulation makes no explicit mention of particle statistics, such an extension is possible, enabling treatment of purported glass formation in systems with a finite superfluid fraction7,8,9.

The fully microscopic QMCT allows for a detailed description of the dynamical phase diagram that separates an ergodic fluid region from an arrested glassy one as a function of both thermodynamic control variables and the parameters (for example ℏ) that control the size of quantum fluctuations. To illustrate this, we carry out detailed QMCT calculations on a hard-sphere system as a function of the system’s volume fraction  and the dimensionless parameter Λ*, which is the ratio of the de Broglie thermal wavelength to the particle size and controls the scale of quantum behaviour. Despite their simplicity, hard-sphere systems are well characterized, experimentally realizable, and show all of the features of glassy behaviour that are exhibited by more complex fluids. It is well known from experiment and simulation that classical hard spheres enter a glassy regime for volume fractions in the range

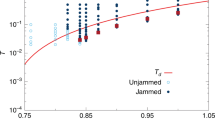

and the dimensionless parameter Λ*, which is the ratio of the de Broglie thermal wavelength to the particle size and controls the scale of quantum behaviour. Despite their simplicity, hard-sphere systems are well characterized, experimentally realizable, and show all of the features of glassy behaviour that are exhibited by more complex fluids. It is well known from experiment and simulation that classical hard spheres enter a glassy regime for volume fractions in the range  =50–60% independent of temperature18,19. Figure 1 shows the full structure of the dynamical phase diagram. The QMCT calculations are consistent with this in the classical limit (Λ*

=50–60% independent of temperature18,19. Figure 1 shows the full structure of the dynamical phase diagram. The QMCT calculations are consistent with this in the classical limit (Λ* 0), but on departure from this show a rather remarkable reentrant behaviour. In particular, as the scale of quantum fluctuations is tuned from small to high values, an initially flat regime is followed by the system becoming glassier and then finally favouring the fluid when quantum fluctuations are large. This behaviour is surprising given the fact that reentrance is not hinted at in the static structure factor. We also show the behaviour produced by a strictly classical MCT calculation carried out with the quantum structure factor as input where only a featureless border separating liquid from glass is demonstrated. This fact clearly shows that the reentrant behaviour predicted by QMCT is a non-trivial product of the properties of the theory and not the static structure factor input.

0), but on departure from this show a rather remarkable reentrant behaviour. In particular, as the scale of quantum fluctuations is tuned from small to high values, an initially flat regime is followed by the system becoming glassier and then finally favouring the fluid when quantum fluctuations are large. This behaviour is surprising given the fact that reentrance is not hinted at in the static structure factor. We also show the behaviour produced by a strictly classical MCT calculation carried out with the quantum structure factor as input where only a featureless border separating liquid from glass is demonstrated. This fact clearly shows that the reentrant behaviour predicted by QMCT is a non-trivial product of the properties of the theory and not the static structure factor input.

is the volume fraction, Λ*=(βℏ2/m σ2)1/2 is the thermal wavelength in units of inter-particle separation σ, and β=1/kBT is the inverse temperature. The approach by which the line separating liquid from glass is determined is given in the Supplementary Information. Inset: Dynamic phase diagram using the quantum mechanical input with a classical MCT.

is the volume fraction, Λ*=(βℏ2/m σ2)1/2 is the thermal wavelength in units of inter-particle separation σ, and β=1/kBT is the inverse temperature. The approach by which the line separating liquid from glass is determined is given in the Supplementary Information. Inset: Dynamic phase diagram using the quantum mechanical input with a classical MCT.

To obtain a physical understanding of this surprising prediction, we turn to the ring-polymer molecular dynamics (RPMD) approach to quantum dynamics20. This method exploits the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics in which a quantum particle is mapped onto a classical ring polymer consisting of a series of replicas linked by harmonic springs. Static properties can be calculated exactly using this mapping while RPMD uses the classical evolution of the polymers to provide an approximation to quantum dynamics. This approach has been previously shown to give accurate dynamical properties for systems ranging from nearly classical to those where tunnelling is dominant21,22.

We carried out RPMD simulations for a binary Lennard-Jones system at a density and temperature that classically exhibits glassy behaviour (details provided in the Supplementary Information)23. Figure 2a shows the change in the diffusion coefficient of the particles as the quantum fluctuations of the system, controlled by varying Λ*, are increased. This property shows the same reentrance seen in the QMCT results. The structure factor, shown in Fig. 2b, reveals only a monotonic broadening over the entire region under study.

a, The diffusion constant as a function of the quantumness, Λ*, obtained from the RPMD simulations for a quantum Kob–Anderson Lennard-Jones binary mixture for T*=2.0 (red curve) and T*=0.7 (black curve). b, Classical and quantum static structure factor of the ‘A’ type particles. c, Root mean square of the radius of gyration as a function of Λ*=0 for the two systems shown in a. The radius of gyration is defined as the average distance of the replicas from the polymer centre.

Analysis of the RPMD trajectories allows us to deduce the origin of this effect. In Fig. 2c, we show the ratio of the average radius of gyration of the polymers representing each particle, a static property given exactly by the RPMD simulations, to its free-particle value, which is proportional to Λ*. The spread of each polymer (or the width of the thermal wave packet) is directly related to the quantum mechanical uncertainty about its position. Hence, the uncertainty principle dictates that decreasing the width of the packet corresponds to an increase in kinetic energy.

The trend in the spread of the particles as shown in Fig. 2c is in excellent agreement with that seen in the diffusion coefficient (see Fig. 2a) and provides insight into the reentrant behaviour. As quantum fluctuations are introduced into the system, the wave packet of each particle attempts to delocalize. Initially (Λ*<0.1), thermally accessible space is available in the system for the particle to expand into, allowing the radius of gyration to increase almost freely. The ratio of the spread of the particles to their free-particle values is near unity and the diffusion is largely unchanged. However, as Λ* is increased further, the width of the packet becomes comparable to the size of the cage in which it resides. There is now little free space into which the packet may expand, leading to a marked decline in the ratio. Figure 3a shows a configuration typical of this regime in which the particle is localized in its cavity. This confinement in its position causes a large rise in the kinetic energy of localization exerting, as Λ* increases, a progressively larger quantum pressure on the cavity.

a,b, Results for the caged (Λ*=0.7) (a) and tunnelling (Λ*=1.3) (b) regimes at T*=0.7. For clarity, all but one ring polymer in each snapshot is represented by its centre of mass. The red spheres represent the replicas of the polymer. Insets: The mean square displacement, 〈|R(t)−R(0)|2〉, calculated from RPMD (solid curves) and classical molecular dynamics (dashed curves) in Lennard-Jones reduced units. The inset of a shows a long beta relaxation regime compared with the classical simulation and the tunnelling case shown in b.

For diffusion to occur, the particles must rearrange in this highly crowded environment. This requires contraction of their wave packets as they pass through the narrow gaps, localizing them further and incurring an additional increase in their kinetic energy. This higher energy required to push through the gaps acts as a bottleneck to diffusion and leads to the slowing reflected in the intermediate Λ* region (see Fig. 2a). This is also shown in the inset of Fig. 3a, which depicts the mean square displacement of the particle. A long intermediate beta relaxation regime is observed in which the particle is caged before being becoming mobile again at long times. When Λ* is raised further, the thermal wavelength becomes comparable to the particle size and the kinetic energy becomes sufficient to flood the barriers between cavities, leading to a rise in the radius of gyration and the occurrence of tunnelling between the cavities, thereby facilitating diffusion. This can be seen in the representative snapshot shown in Fig. 3b in which the particle is stretched across two cavities. Accordingly, the ratio of the radius of gyration to its free value recovers with a corresponding increase in diffusion and diminishing of the caging regime as shown in the inset of Fig. 3b.

The theory we have developed for the quantum glass transition predicts interesting generic dynamical anomalies such as a reentrant border between the disordered arrested and fluid regimes. Semi-classical quantum dynamics simulations exhibit similar features and physically illuminate the origin of the predicted relaxation motifs. The physical interplay between crowding and quantum delocalization reported here, a generic feature of quantum glassy systems, might also be responsible for other physical phenomena. For example, it has been experimentally observed that lighter isotopes of hydrogen diffuse more slowly than heavier ones in water24 and palladium25, which has been recently elucidated by theory26. Therefore, behaviour similar to our predicted reentrance has been observed in chemical systems. However, although the two approximate methods, RPMD semi-classical simulations and QMCT theory, predict a consistent picture, the exact degree of the reentrance may be less pronounced in physical systems27.

It is likely that the reentrant transition observed here may also have implications beyond glassy systems. Intuition suggests that increasing quantum fluctuations monotonically enhances the exploration of the energy landscape. This forms the basis of the quantum annealing approach to optimization28,29. However, our work indicates that in certain regimes increasing quantum fluctuations can lead to dynamical arrest and hinder optimization. Indeed, reentrance has recently been observed in the dynamical phase behaviour of simple models of quantum optimization under investigation in the field of quantum information science30. Thus, deep connections exist that unite these seemingly distinct physical systems and processes.

References

Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 410, 259–267 (2001).

Berthier, L. et al. Direct experimental evidence of a growing length scale accompanying the glass transition. Science 310, 1797–1800 (2005).

Biroli, G. et al. Thermodynamic signature of growing amorphous order in glass-forming liquids. Nature Phys. 4, 771–775 (2008).

Hedges, L. O., Jack, R. L., Garrahan, J. P. & Chandler, D. E. Dynamic order–disorder in atomistic models of structural glass formers. Science 323, 1309–1313 (2009).

Amir, A., Oreg, Y. & Imry, Y. Slow relaxations and aging in the electron glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 126403 (2009).

Wu, W. H. et al. From classical to quantum glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 2076–2079 (1991).

Boninsegni, M., Prokof’ev, N. & Svistunov, B. Superglass phase of 4He. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 105301 (2006).

Biroli, G., Chamon, C. & Zamponi, F. Theory of the superglass phase. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224306 (2008).

Hunt, B. et al. Evidence for a superglass state in solid 4He. Science 324, 632–636 (2009).

Götze, W. Complex Dynamics of Glass-Forming Liquids: A Mode-Coupling Theory (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009).

Biroli, G., Bouchard, J., Miyazaki, K. & Reichman, D. R. Inhomogeneous mode-coupling theory and growing dynamic length in supercooled liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 195701 (2006).

Dawson, K. et al. Higher-order glass-transition singularities in colloidal systems with attractive interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 011401 (2001).

Götze, W. & Voightmann, Th. Effect of composition changes on the structural relaxation of a binary mixture. Phys. Rev. E 67, 021502 (2003).

Zaccarelli, E. et al. Confirmation of anomalous dynamical arrest in attractive colloids: A molecular dynamics study. Phys. Rev. E 66, 041402 (2002).

Foffi, G. et al. Mixing effects for the structural relaxation in binary hard-sphere liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 085701 (2003).

Pham, K. N. et al. Multiple glassy states in a simple model system. Science 296, 104–106 (2002).

Götze, W. & Lücke, M. Dynamical structure factor S(q,ω) of liquid helium II at zero temperature. Phys. Rev. B 13, 3825–3842 (1976).

Pusey, P. N. & van Megen, W. Observation of a glass transition in suspensions of spherical colloidal particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2083–2086 (1987).

Foffi, G. et al. α-relaxation processes in binary hard-sphere mixtures. Phys. Rev. E 69, 011505 (2004).

Craig, I. R. & Manolopoulos, D. E. Quantum statistics and classical mechanics: Real time correlation functions from ring polymer molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 3368–3373 (2004).

Miller, T. F. & Manolopoulos, D. E. Quantum diffusion in liquid water from ring polymer molecular dynamic. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 154504 (2005).

Richardson, J. O. & Althorpe, S. C. Ring-polymer molecular dynamics rate-theory in the deep-tunneling regime: Connection with semiclassical instanton theory. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 214106 (2009).

Kob, W. & Andersen, H. C. Testing mode-coupling theory for a supercooled binary Lennard-Jones mixture I: The van Hove correlation function. Phys. Rev. E 51, 4626–4641 (1995).

Rounder, E. Hydrophobic solvation, quantum nature, and diffusion of atomic hydrogen in liquid water. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 72, 201–206 (2005).

Wipf, H. Hydrogen in Metals III: Properties and Applications (Springer, 1997).

Markland, T. E., Habershon, S. & Manolopoulos, D. E. Quantum diffusion of hydrogen and muonium atoms in liquid water and hexagonal ice. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 194506 (2008).

Westfahl, H., Schmalian, J. & Wolynes, P. G. Dynamical mean-field theory of quantum stripe glass. Phys. Rev. B 68, 134203 (2003).

Lee, Y. & Berne, B. J. Global optimization: Quantum thermal annealing with path integral Monte Carlo. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 86–95 (2000).

Das, A. & Chakrabati, B. K. Quantum annealing and analog quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1061–1081 (2008).

Foini, L., Semerjian, G. & Zamponi, F. Solvable model of quantum random optimization problems. Phys. Rev. Lett 105, 167204 (2010).

Acknowledgements

B.J.B. acknowledges support from NSF grant No. CHE-0910943. D.R.R. would like to thank the NSF through grant No. CHE-0719089. K.M. acknowledges support from Kakenhi grant No. 21015001 and 2154016. The authors acknowledge G. Biroli and L. Cugliandolo for useful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R.R. and E.R. developed the QMCT approach. K.M. and E.R. carried out the QMCT calculations. T.E.M. carried out the RPMD calculations and analysed the results with B.J.B. and J.A.M. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 283 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Markland, T., Morrone, J., Berne, B. et al. Quantum fluctuations can promote or inhibit glass formation. Nature Phys 7, 134–137 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1865

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1865

This article is cited by

-

Energy of a free Brownian particle coupled to thermal vacuum

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Quantum effects on dislocation motion from ring-polymer molecular dynamics

npj Computational Materials (2018)

-

A Tentative Replica Theory of Glassy Helium 4

Journal of Low Temperature Physics (2012)

-

Quantum glass forging

Nature Physics (2011)