Abstract

In superconductors, electrons are paired and condensed into the ground state. An impurity can break the electron pairs into quasiparticles with energy states inside the superconducting gap. The characteristics of such in-gap states reflect accordingly the properties of the superconducting ground state1. A zero-energy in-gap state is particularly noteworthy, because it can be the consequence of non-trivial pairing symmetry1 or topology2,3. Here we use scanning tunnelling microscopy/spectroscopy to demonstrate that an isotropic zero-energy bound state with a decay length of ∼10 Å emerges at each interstitial iron impurity in superconducting Fe(Te,Se). More noticeably, this zero-energy bound state is robust against a magnetic field up to 8 T, as well as perturbations by neighbouring impurities. Such a spectroscopic feature has no natural explanation in terms of impurity states in superconductors with s-wave symmetry, but bears all the characteristics of the Majorana bound state proposed for topological superconductors2,3, indicating that the superconducting state and the scattering mechanism of the interstitial iron impurities in Fe(Te,Se) are highly unconventional.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Superconductivity arises from the macroscopic quantum condensation of electron pairs—Cooper pairs. The symmetry of the wavefunction of these pairs is one of the most essential aspects of the microscopic pairing mechanism. The impurity-induced local density of states (LDOS) is sensitive to the pairing symmetry; therefore it can be used to test the symmetry of the order parameter and to probe the microscopic pairing mechanism. Being a local probe with atomic resolution, scanning tunnelling microscopy/spectroscopy (STM/S) has played a key role in this respect, especially in the study of high-TC cuprate superconductors4,5.

Since its discovery, new compounds of iron-based superconductor (IBSC) continue to be found. However, the pairing symmetry remains a central unresolved issue. So far, STM/S studies regarding impurity scattering in single crystals of IBSCs have been limited to either weak scattering or unidentified impurities6,7,8, or impurity-assisted quasi-particle interference9,10. In our systematic experiments on various IBSCs, we have found that excess iron atoms in Fe(Te,Se) are unique impurities that induce strong local in-gap states. These excess iron atoms are known to suppress superconductivity efficiently11,12. Therefore, a single crystal of Fe(Te,Se) containing a controlled amount of excess iron is considered a natural and promising system for experiments on single atomic impurities.

The as-grown Fe1+x(Te,Se) single crystals contain a large amount of excess iron that exists as single iron atoms randomly situated at the interstitial sites between the two (Te,Se) atomic planes. The removal of these interstitial iron impurities (IFIs) can be controlled well by an annealing process13. The highest TC is obtained when all the IFIs are removed. In Fig. 1a, we present an STM topographic image of a cleaved pristine Fe(Te,Se) single crystal (TC = 14.5 K), revealing the (Te,Se)-terminated surface, with the brighter spots being Te atoms and the less bright spots being Se atoms (Supplementary Information 1). At temperatures where the crystal is deep in the superconducting state, the tunnelling spectrum exhibits a pair of sharp peaks at ±1.5 meV and a pair of side peaks at ±2.5 meV, together with a stateless region between the ±1.5 meV peaks, as shown in Fig. 1b. We identify the two pairs of peaks as superconducting coherent peaks, owing to their energy scales matching well with the two superconducting energy gaps observed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES; ref. 14) and their disappearance at temperatures above the bulk superconducting transition temperature TC. These spectral features seemingly suggest an s-wave-like9, multi-gap nature of the superconducting state in Fe(Te,Se). The s-wave-like gaps are found to be spatially homogeneous, as shown in Fig. 1c, thus providing us a clear background against which to ‘view’ the in-gap states induced by an individual IFI.

a, Topographic image of (Te,Se) (180 × 180 Å, T = 1.5 K, V = −100 mV, I = 0.1 nA). Inset image is the crystal structure of Fe(Te,Se). b, Comparison between STS and ARPES data. The upper panel shows STS taken on the (Te,Se) surface (T = 1.4 K, V = −10 mV, I = 0.3 nA). The lower panel shows symmetrized ARPES spectra14. c, STS spectra taken along the line shown in a.

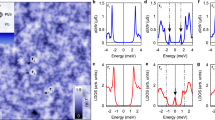

In the image of a crystal with 0.5% IFI (TC = 12 K), one can easily identify the IFI atoms, showing as bright spots scattered on the exposed (Te,Se) surface, as shown in Fig. 2a, which is consistent with previous work by other groups10,15. To pin-point the exact location of the IFIs, we zoom onto a single IFI (Fig. 2b), and find that it is located right at the mid-position of the four neighbouring Te/Se atoms (inset of Fig. 2a)16,17. Spectroscopically, the individual IFI manifests itself as a sharp spectral peak precisely at zero bias (Fig. 2d). Such a zero-energy spectral peak is accompanied by a low-energy DOS depression without coherent peaks, which is in sharp contrast to the spectra taken far away from the IFIs, suggesting a strong local scattering caused by the IFI and the consequential suppression of superconductivity. It has been repeatedly verified that these spectral features are not dependent on the tunnelling junction resistance.

a, Topographic image of the (Te,Se) surface (200 × 200 Å). Inset image is the crystal structure of Fe1+x(Te,Se) with an IFI on the surface (Te,Se) layer16. b, Zoomed-in image showing an IFI surrounded by four ‘bright’ Te/Se atoms. c, Averaged topographic profile over all the IFI atoms in a. d, Spectra taken at and away from the IFI. All the data are acquired at 1.5 K.

To better reveal the characteristics of such local effects, we study single IFI atoms in a sample with a miniscule IFI content (x = 0.1%, TC = 14 K), as shown in Fig. 3a. A stronger zero-energy bound state (ZBS) peak is observed in the tunnelling spectrum taken at the centre of the IFI site, as shown in Fig. 3b. The spatial pattern of this ZBS is almost circular, as seen from the zero-energy map in Fig. 3e, which is very different from the cross-shape pattern of the Zn impurity in Bi2Sr2Ca(Cu, Zn)2O8+δ (ref. 4), indicating that the IFI scattering is fairly isotropic. This can also be verified by the nearly identical spectra measured along a circle around the IFI (Fig. 3c). The ZBS is also localized, visible only within a region of ∼10 Å in diameter. A more quantitative analysis, by fitting the zero-bias spectral peak measured along a line departing from the IFI (Fig. 3d), demonstrates an exponential decay of the ZBS intensity with a characteristic length of ξ = 3.5 Å (Fig. 3f), which is almost one order of magnitude smaller than the typical coherent length of ∼25 Å in the IBSCs (refs 18, 19). More significantly, the ZBS remains a single peak, strictly at zero energy, when measured away from the centre of the IFI site. It is worthwhile pointing out that the integrated low-energy DOS remains nearly constant (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the spectral weight of the ZBS comes primarily from the superconducting coherent peaks. Moreover, the magnitude of the superconducting gap is unaffected by the IFI (Fig. 3c, d), suggesting that the IFI weakens only the superconducting phase coherence, but not the strength of the superconducting pairs.

a, Topographic image of an isolated single IFI (100 × 100 Å). b, Spectra taken on top of and away from the IFI. c, Spectra taken along the circle in a (r = 5 Å). d, Spectra taken along the line in a (θ = 0). e, Zero-energy map for the area boxed in a. f, Zero-energy peak value N(0) versus distance r from IFI (data extracted from the spectra in d and normalized to the peak and bottom value). The solid curve is an exponential fit with ξ = 3.5 Å. Inset is a schematic image for the spatial distribution of IFI scattering. g, Topographic image of the same area as a with the IFI removed by the STM tip. h, Spectrum taken at the original position of the removed IFI. All the data are acquired at 1.5 K.

To confirm that the observed ZBS is indeed induced by an IFI, we use the STM to remove an individual IFI atom. As demonstrated in Fig. 3g, h, after removal of the IFI atom, superconductivity is fully recovered at the original site of the removed IFI, and the tunnelling spectrum becomes identical to the spectra taken at the locations without IFIs.

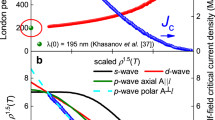

Another aspect of this ZBS spectral peak is its narrow linewidth. By removing the convolution effect of the finite-temperature Fermi–Dirac distribution function, we find the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of this Lorentzian peak to be 0.6 meV, as shown in Fig. 4a. This sharp ZBS peak broadens rapidly when the temperature is raised, and vanishes completely at 15 K (just above the bulk TC; Fig. 4a, inset), which attests to the intimate relation between the ZBS and the bulk superconductivity.

a, Circular markers represent the raw data taken at 1.5 K. Solid curve represents the spectrum of the raw data deconvoluted by the Fermi–Dirac distribution function of 1.5 K. The inset shows the spectra taken at the same IFI at different temperatures. b, High-resolution ZBS spectra (Vmod = 0.06 mV) measured at 0 T and in a magnetic field of 8 T along the c-axis. The blue dashed line with arrows at both ends marks the expected Zeeman splitting energy at 8 T (g = 2). The inset shows the spectra taken at the same IFI under different magnetic fields. The blue V-shaped dashed line is a guide to the eye showing the expected Zeeman splitting (g = 2). c, Topographic image showing two IFI atoms close in space (60 × 60 Å). d, Spectra taken at the two IFI sites as shown in c. All spectra are offset for clarity.

As a result of breaking time-reversal symmetry, an external magnetic field can cause a ZBS peak to split. To our surprise, the ZBS peak observed on the IFIs remains unchanged under external magnetic fields. As demonstrated in the inset of Fig. 4b, the ZBS peak is not split, shifted or suppressed by an external magnetic field up to 8 T along the c-axis. In a typical spin-degenerate system (g = 2), the Zeeman splitting is expected to be ∼0.9 meV at 8 T, which would have been easily detected by our high-resolution STS (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the ZBS peak remains at zero energy even when two IFI atoms are located near each other (∼15 Å), as shown in Fig. 4c, d. This is quite unexpected, since two degenerate states will split when coupled quantum mechanically. However, the ZBS peaks of the two closely located IFI atoms are found to be suppressed in intensity, as compared with the ZBS at a single IFI, possibly due to the local suppression of superconductivity or destructive interference.

It seems to be a serious challenge to consistently explain the ZBS induced by individual IFI atoms. Our observation of an s-wave-like full gap seemingly suggests the pairing symmetry to be of the centrally debated s++ or s± type20. However, for either symmetry, the in-gap bound states of a classical magnetic or non-magnetic impurity generally form a pair of spectral peaks, symmetrically placed with respect to zero energy7,21,22,23. Incidentally, both of these two peaks can be of zero energy, but they will Zeeman-split when a magnetic field is applied. Although the Kondo impurity resonance is a single peak, it usually departs slightly from zero energy due to finite potential scattering in the superconducting state and should Zeeman-split as well1. The only known superconducting state that allows a ZBS is the d-wave pairing state with an impurity at unitary limit1. However, for this symmetry, quasi-particles tend to ‘leak’ along the nodal directions, forming a real-space spectral pattern with four-fold symmetry4,5. It is evident that our observations of the isotropic ZBS induced in the background of s-wave-like superconductivity are drastically inconsistent with conventional impurity effects in either d- or s-wave superconductors.

The inaptness of the aforementioned conventional explanations for the main aspects of our experimental observations naturally prompts us to consider that the emergence of the ZBS is an indication of a highly novel and complex superconducting state in Fe(Te,Se). In fact, compared with impurities previously investigated, the single-atom iron impurity is located at the specific interstitial position with high symmetry24 and modifies the local electronic structure in a very unique way, as shown in the Supplementary Information. We also note that, unlike FeSe, where previous STM studies did not observe such ZBS (ref. 25), the heavy 5p Te atoms in Fe(Te,Se) have a strong spin–orbit coupling that can significantly alter the electronic structure and the properties of the superconducting state, including the symmetry of the Cooper pairs. Moreover, neutron scattering experiments found that excess Fe induces local magnetic ordering with a sizeable moment17. Thus, a firm understanding of the observed ZBS would require detailed knowledge of the interplay among spin–orbit coupling, s-wave-like superconductivity, and the short-range magnetic order. It has not escaped our attention that a zero-energy fermionic peak which does not split under a magnetic field is almost equivalent to the spectroscopic definition of a Majorana fermion2,3, suggesting the topological aspect of this state.

References

Balatsky, A. V., Vekhter, I. & Zhu, J-X. Impurity-induced states in conventional and unconventional superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 373–433 (2006).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Linder, J., Tanaka, Y., Yokoyama, T., Sudbø, A. & Nagaosa, N. Unconventional superconductivity on a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 067001 (2010).

Pan, S. H. et al. Imaging the effects of individual zinc impurity atoms on superconductivity in Bi2Sr2Ca(Cu, Zn)2O8+δ . Nature 403, 746–750 (2000).

Hudson, E. W. et al. Interplay of magnetism and high-Tc superconductivity at individual Ni impurity atoms in Bi2Sr2Ca(Cu, Zn)2O8+δ . Nature 411, 920–924 (2001).

Wang, Z. et al. Close relationship between superconductivity and the bosonic mode in Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 and Na(Fe0.975Co0.025)As. Nature Phys. 9, 42–48 (2013).

Yang, H. et al. In-gap quasiparticle excitations induced by non-magnetic Cu impurities in Na(Fe0.96Co0.03Cu0.01)As revealed by scanning tunnelling spectroscopy. Nature Commun. 4, 2749 (2013).

Grothe, S. et al. Bound states of defects in superconducting LiFeAs studied by scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 86, 174503 (2012).

Hanaguri, T., Niitaka, S., Kuroki, K. & Takagi, H. Unconventional s-wave superconductivity in Fe(Se, Te). Science 328, 474–476 (2010).

Allan, M. P. et al. Anisotropic energy gaps of iron-based superconductivity from intraband quasiparticle interference in LiFeAs. Science 336, 563–567 (2012).

Liu, T. J. et al. Charge-carrier localization induced by excess Fe in the superconductor Fe1+yTe1−xSex . Phys. Rev. B 80, 174509 (2009).

Rößler, S. et al. Disorder-driven electronic localization and phase separation in superconducting Fe1+yTe0.5Se0.5 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 82, 144523 (2010).

Taen, T., Tsuchiya, Y., Nakajima, Y. & Tamegai, T. Superconductivity at Tc ∼ 14 K in single-crystalline FeTe0.61Se0.39 . Phys. Rev. B 80, 092502 (2009).

Miao, H. et al. Isotropic superconducting gaps with enhanced pairing on electron Fermi surfaces in FeTe0.55Se0.45 . Phys. Rev. B 85, 094506 (2012).

Massee, F. et al. Cleavage surfaces of the BaFe2−xCoxAs2 and FeySe1−xTex superconductors: A combined STM plus LEED study. Phys. Rev. B 80, 140507(R) (2009).

Li, S. et al. First-order magnetic and structural phase transitions in Fe1+ySexTe1−x . Phys. Rev. B 79, 054503 (2009).

Thampy, V. et al. Friedel-like oscillations from interstitial iron in superconducting Fe1+yTe0.62Se0.38 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 107002 (2012).

Yin, Y. et al. Scanning tunneling spectroscopy and vortex imaging in the iron pnictide superconductor BaFe1.8Co0.2As2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 097002 (2009).

Shan, L. et al. Observation of ordered vortices with Andreev bound states in Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 . Nature Phys. 7, 325–331 (2011).

Hirschfeld, P. J., Korshunov, M. M. & Mazin, I. I. Gap symmetry and structure of Fe-based superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124508 (2011).

Yazdani, A., Jones, B. A., Lutz, C. P., Crommie, M. F. & Eigler, D. M. Probing the local effects of magnetic impurities on superconductivity. Science 275, 1767–1770 (1997).

Tsai, W-F., Zhang, Y-Y., Fang, C. & Hu, J. P. Impurity-induced bound states in iron-based superconductors with s-wave cosk x ⋅ cosk y pairing symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 80, 064513 (2009).

Zhang, D. Nonmagnetic impurity resonances as a signature of sign-reversal pairing in FeAs-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 186402 (2009).

Hu, J. P. Iron-based superconductors as odd-parity superconductors. Phys. Rev. X 3, 031004 (2013).

Song, C-L. et al. Direct observation of nodes and twofold symmetry in FeSe superconductor. Science 332, 1410–1413 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Z. Fang, X. Dai, T. Xiang, D-H. Lee, T-K. Lee, G-M. Zhang and P. Coleman for stimulating discussions. This work is supported by the State of Texas through TcSUH, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, US Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-09-1-0656), Robert A. Welch Foundation (E-1146), US DOE (DE-SC0002554, DE-FG02-99ER45747), National Science Foundation of China (11322432, 11190020), and Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012CB933000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J-X.Y. carried out the STM/S experiments with contributions from Z.W., J-H.W., Z-Y.Y., J.G., X-Y.H., L.S., A.L. and X-J.L.; Z.W. synthesized and characterized the sequence of samples; J-X.Y., S.H.P. and H.D. performed the data analysis, figure development and wrote the paper with contributions from J-P.H., Z-Q.W., C-S.T., P-H.H., J.L. and X-X.W.; S.H.P. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and the interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 725 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, JX., Wu, Z., Wang, JH. et al. Observation of a robust zero-energy bound state in iron-based superconductor Fe(Te,Se). Nature Phys 11, 543–546 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3371

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3371

This article is cited by

-

Dislocation Majorana bound states in iron-based superconductors

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Emergent ferromagnetism with superconductivity in Fe(Te,Se) van der Waals Josephson junctions

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Effective impurity behavior emergent from non-Hermitian proximity effect

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Roadmap of the iron-based superconductor Majorana platform

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

-

Two-dimensional superconductors with intrinsic p-wave pairing or nontrivial band topology

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)