Abstract

The ability to send a wave to fetch an object from a distance would find a broad range of applications. Quasi-standing Faraday waves on water create horizontal vortices1,2, yet it is not known whether propagating waves can generate large-scale flows—small-amplitude irrotational waves only push particles in the direction of propagation3,4,5. Here we show that when waves become three-dimensional as a result of the modulation instability, a floater can be forced to move towards the wave source. The mechanism for this is the generation of surface vortices by waves propagating away from vertically oscillating plungers. We introduce a new conceptual framework for understanding wave-driven flows, which enables us to engineer inward and outward surface jets, stationary vortices, and other complex flows. The results form a new basis for the remote manipulation of objects on fluid surfaces and for a better understanding of the motion of floaters in the ocean, the generation of wave-driven jets, and the formation of Lagrangian coherent structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

What is perceived as fluid motion on a surface perturbed by waves is a motion of the surface shape, not the fluid flow along the surface6. Trajectories of fluid parcels on the surface have been described analytically for progressing irrotational waves, where particles move in the direction of wave propagation3,4,5,7,8,9. Such waves are rare in nature and in the laboratory because finite-amplitude waves are unstable with respect to amplitude modulation, a phenomenon also known as the Benjamin–Feir instability10. Two-dimensional (2D) waves of finite amplitude develop into 3D waves, forming complex wave patterns11,12,13,14. The motion of particles on the surface of such wave fields is not understood. It has been found recently that Faraday waves, which are parametrically excited 3D nonlinear waves, create vortices on the fluid surface that interact and lead to the development of 2D turbulence1,15. The generation of horizontal vortices by quasi-standing nonlinear waves2 is an effect which is impossible in planar irrotational waves. In this paper we show that progressing nonlinear waves produced by a localized source are also capable of creating surface vortices. The interaction between such vortices is shown to lead to the formation of large-scale surface flows, far away from a wave maker.

In our experiments we generate progressing waves using vertically moving plungers, periodically inserted into the water. The wave fields are visualized using a diffusive light imaging technique16 and fast video imaging of tracer particles on the fluid surface. The 3D fluid particle trajectories are tracked using a novel method, developed as part of this work, which is described in Methods and the Supplementary Information.

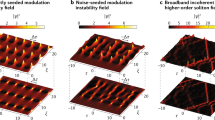

A cylindrical wave maker oscillates at low amplitude, as illustrated in the schematic of Fig. 1g (for details of the experimental set-up see Supplementary Section 1). The wave maker produces nearly planar propagating wavefronts, as seen in Fig. 1a. To visualize the fluid motion, buoyant tracer particles are uniformly dispersed over the fluid surface. The particles are pushed in the direction of the wave propagation, forming an outward jet, as seen in the time-averaged particle streak image of Fig. 1b. As a consequence, a compensating return flow converges towards the sides of the wave maker. The flow changes markedly as the wave amplitude is increased above the threshold for the onset of the modulation instability17,18 (Fig. 1c, d). As the modulation grows and the cross-wave instability breaks the wavefront into trains of propagating pulses, the wave field becomes three-dimensional (see Fig. 1c, as well as Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Movie 1). Simultaneously, the direction of the central jet reverses. It now pushes floaters towards the wave maker and against the wave propagation. The flow is strong enough to move floating objects far from the plunger on the water surface (see Supplementary Movie 2). The motion of the floater can thus be reversed simply by changing the amplitude of the wave maker oscillations.

a, Top view of the wave field produced by the cylindrical wave maker (25 mm diameter, 130 mm long) at lower acceleration (f = 20 Hz, wavelength λ = 12 mm, acceleration a = 0.8g). It shows nearly planar waves propagating away from the wave maker (seen at the top of the panel). b, The waves produce a strong outward jet in the direction of the wave propagation (thick blue arrow) and the return flows towards the edges of the cylinder (thin red arrows). Thick grey lines between the streak images show the tank walls. c, As the wave maker acceleration is increased (a = 1.2g) the modulation instability destroys the wave planarity, generating the 3D wave field shown here. Pink and blue wave fields correspond to two consecutive periods of the wave maker phase. d, This 3D wave field generates a strong inward directed jet towards the centre of the cylinder (thick red arrow) and the outward return flows away from the edges of the cylinder (thin red arrows). See the corresponding Supplementary Movie 3. e, Particle streaks in the vicinity of the cylindrical wave maker allow one to visualize the region of Lagrangian stochastic transport. Turbulence pumps particles away in the direction of red arrows, orthogonal to the wave propagation. f, Central jet velocity measured 120 mm away from the wave maker versus vertical acceleration of the plunger (in units of the gravitational acceleration g). Green dots show measured velocities, orange error bars show the standard deviation. Blue, orange and red lines guide the eye. See the corresponding Supplementary Movies 3 and 4. Inward and outward jets are strong enough to manipulate objects on the water surface. For an example with a ping-pong ball, see Supplementary Movie 2. g, Schematic of the experimental set-up.

What is the reason for the flow reversal? In the nonlinear regime the transverse modulation of the wavefronts is strongest (highest amplitude) in the near field (one to two wavelengths away from the wave maker), where soliton-like propagating pulses 18 are generated, as seen in the digital representation of the experimentally measured surface elevation (Fig. 1c). The reversal of the mean flow in the far field (tens or hundreds of wavelengths away from the wave maker) is always correlated with the generation of stochastic Lagrangian trajectories within a flow region in front of the wave maker (Fig. 1e). This localized complex chaotic flow efficiently transports fluid in the direction perpendicular to the propagation of the wave pulses. The net result is a stochastic pumping, which seems to be responsible for the ejection of surface fluid parcels parallel to the wave maker. This transport is compensated by the fluid flow towards the centre of the wave source, forming a ‘tractor beam’ against the wave propagation. The velocity of the central jet changes gradually with the increase in the vertical acceleration of the wave maker. As shown in Fig. 1f, at low amplitudes, the flow is outwards and the velocity increases with the increase in forcing. When the threshold of the modulation instability is reached, the flow reverses abruptly and the inward jet velocity saturates at higher forcing levels. Such a behaviour is observed for a wide range of excitation frequencies, from 10 to 200 Hz.

The outward/inward central jets are compensated by the return flows towards/away from the sides of a cylindrical wave maker (Fig. 1b, d). These return flows are guided by the walls of the wave tank forming the dipole structures on both sides of the wave maker. The larger the tank, the larger are the vortices forming dipoles (this was confirmed by performing experiments in different tanks). If one guides the return flow by introducing baffles isolating central jets from the return flow, as shown in Fig. 2a, the lengths of the central jets can be greatly increased. In this configuration, the widths of the jets are determined by the width of the cylindrical wave maker. Figure 2b shows the mean velocity of the central jet inside the channel formed by the baffles as the forcing is increased. The presence of the baffles does not affect the flow reversal of the jet above the threshold of modulation instability, consistent with the case of no baffles (Fig. 1f). Above the threshold, the inward mean flow velocity grows with increasing vertical acceleration and then saturates. Such a trend is found for a wide range of excitation frequencies, as illustrated in Fig. 2c. The mean flow velocity is approximately constant as a function of the distance from the wave maker (see Fig. 2d for an example). In these experiments the tractor beam extends over several hundreds of wavelengths. To obtain efficient pumping, the length of the cylindrical plunger should greatly exceed the length of the cross-wave (the experiments suggest that the mode number of the cross-wave should be greater than ten).

a, Schematic of a flow in the tractor beam regime where the inward jet is isolated from the return flow using baffles (black). Baffles allow the extension of the tractor beam over distances hundreds of wavelengths away from the wave maker. b, Jet velocity in the direction of the wave propagation measured 29 wavelengths away from the wave maker as a function of the vertical acceleration of the plunger at an excitation frequency of 20 Hz (λ = 12 mm). At lower acceleration, the velocity V (x) is positive (in the direction of wave propagation), whereas at higher acceleration, in the nonlinear regime, the jet reverses its direction. Blue, orange and red lines guide the eye. c, The velocities of the inward jet (tractor beam) measured at different excitation frequencies, ranging from 60 to 200 Hz (λ = (5–2.2) mm respectively), at a distance from the plunger Xm = 350 mm. d, The jet velocity measured at an excitation frequency of 100 Hz (λ = 3.5 mm) for different vertical accelerations of the plunger as a function of the distance from the wave maker. e, Depth profile of the jet velocity (z = 0 at the water surface). The flow is visualized by imaging suspended particles, which are illuminated using a vertical laser sheet. The main plot illustrates the jet velocity normalized by the velocity at the water surface Vx/Vsurf versus the distance from the surface at excitation frequencies of 60 Hz (green circles) and 100 Hz (red circles). The inset shows the velocity profiles in both the planar wave (dark blue circles) and modulated wave (orange circles) regimes at an excitation frequency of 20 Hz.

Although the mean flow is driven by waves, which significantly affect the fluid motion only near the plunger, the mean inward flow establishes far from the wave maker. This is unexpected, especially at the higher excitation frequencies, where the viscous dissipation is very high and waves decay at distances of less than ten wavelengths. The flow that develops is quasi-two-dimensional: the jets are sustained in a rather narrow layer at the water surface. Figure 2e shows the vertical profile of the jet velocity, which decays very fast with the depth, in a layer of about 10–15 mm. Thus, the depth of the water in these experiments (80 mm) does not affect any results reported here.

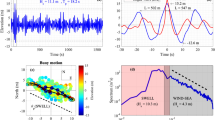

To understand how the stochastic region forms in front of the cylindrical wave maker, we performed experiments using various plunger shapes. If one uses a conical wave maker at low amplitudes, nearly circular wavefronts are produced (Supplementary Fig. 1g). Above the modulation instability threshold, at higher acceleration, the wave amplitude becomes modulated in the transverse direction, forming a complex 3D wave field (Fig. 3a) similar to the cylinder case. The wave field is made of periodic pulses propagating away from the cone in the radial direction. The surface flow pattern in this case is rather complex, exhibiting vortices of different sizes (Fig. 3b). To better understand the origin of the steady-state flow pattern, we have obtained flow data during the start-up phase, when nonlinear waves are formed during the onset of the modulation instability. The vorticity ω = (∂Vy/∂x − ∂Vx/∂y) (where Vx and Vy are horizontal velocity components) is initially created in the vicinity of the plunger, where waves are the steepest. A circular array of counter-rotating vortices is formed (Fig. 3c). Then, two rows of vortices are formed (Fig. 3d). Finally, vortices spread in the direction of the wave propagation, as seen in Fig. 3e, f. This result indicates that the ability of waves to create vorticity is not limited to Faraday quasi-standing waves2. As shown, propagating nonlinear 3D waves also inject vorticity into the surface flow.

a, Waves produced by a symmetric conical plunger at a frequency f = 20 Hz and at an acceleration above the threshold of the modulation instability18. The wave field consists of periodic radially propagating pulses. Pink and blue wave fields correspond to two consecutive periods of the wave maker phase. b, Surface flow pattern produced by the 3D wave field. A chain of spatially and temporally stationary vortices forms near the wave maker. c–f, Temporal development of vorticity on the water surface: Horizontal vortices developed at t = 0.2 s (c), t = 0.5 s (d), t = 1 s (e) and t = 2 s (f) after the development of the 3D wave field.

The larger vortices seen in Fig. 3b further away from the wave maker are not generated at the increased liquid viscosity. This regime allows better visualization of the underlying mechanism of vorticity generation by propagating waves close to the plunger. By increasing the liquid viscosity, we restrict the number of vortices in the surface flow, as shown in Fig. 4d. The visualization of the 3D floater trajectories and waves reveals that particles which are close to the maxima of the wave pulses move away from the wave maker, as seen in Fig. 4a–c. Further away they start to drift sideways and then reverse direction to move towards the wave source along the trajectories where wave heights are lower. The shapes of the 3D trajectories are not trochoids (curves with loops), as expected from the small-amplitude wave models, but rather complex modulated trajectories, indicating no resemblance to the classical Stokes drift picture.

To restrict the vortex interaction in front of the wave maker, the viscosity of the liquid is increased by performing measurements in a 45% solution of sucrose in water (its viscosity is 9.3 times higher than that of water). a, Top view of the measured 3D particle trajectories superimposed on the measured 3D wave field: dark and light blue wave fields correspond to two consecutive periods of the wave maker phase. Trajectory #1 shows particle motion within a smaller vortex. Trajectory #2 shows an outward propagating particle, whereas trajectory #3 shows a particle travelling towards the wave maker along the wave minima, against the wave propagation, and then turning radially outward along the wave maxima. b,c, are the same trajectories shown in a viewed from different angles. d, Time-averaged particle streaks near the wave maker (the wave maker is at the top of the figure) show strong azimuthally periodic outward and inward radial jets (blue and red arrows respectively). Counter-rotating stationary vortices are found between these jets. e, Velocity field of this flow measured using the particle image velocimetry technique. f, Finite-time Lyapunov exponent field Λ(x, y) visualizes regions of the largest divergence of adjacent Lagrangian trajectories in the flow. Red–orange lines mark the ridges of the maximum of the Lyapunov exponent. These lines outline the boundaries of the outward jets seen in d and e.

In the conical plunger case, strong outward jets are formed along the wave maxima. These jets are clearly seen in the averaged particle streak photographs and in the velocity fields (Fig. 4d, e). The jets diverge and form stationary vortices, as seen in the flow velocity field of Fig. 4e. The vorticity generation here is similar to that produced by Kelvin–Helmholtz instability in Rayleigh–Taylor turbulence19. This divergence of jets can be visualized by computing the Lyapunov exponents of the Lagrangian trajectories20 (Fig. 4f). The ridges of the maxima of the Lyapunov exponents, Λ, mark the boundaries of the jet stability (see Methods for details of the computation of Λ). Adjacent diverging jets form stable closed vortices.

Wave-jet-driven vortices always form in the near field of any wave maker as soon as waves become unstable and three-dimensional. In the case of the conical plunger the elliptical vortices are aligned along a distinct radial direction, whereas in the case of a cylinder these vortices are tightly packed such that they interact more strongly. The Lagrangian chaos in the near field of the cylinder appears as a result of the interaction between wave-driven vortices being pushed closer together.

Vorticity creation by steep 3D waves is thus responsible for the unexpected effect reported here—the generation of the tractor beam, or the inward jet, which moves particles against the wave propagation. The degree of interaction between wave-driven surface vortices depends on the shape of the plunger. It increases from conical to elliptical (see Supplementary Information), and to cylindrical wave makers.

The above results suggest new principles for generating surface flows using localized wave sources. The geometry of the flow depends on the shape of the wave maker and on the state of the wave field in front of the wave maker. Examples of various surface flows produced by different wave makers are discussed in Supplementary Section 4. By using triangular and square pyramidal wave makers it is possible to generate flows having threefold and fourfold patterns. Above the threshold of the modulation instability, the directions of jets and the return flows reverse, similarly to the case of a cylindrical plunger discussed here. All these methods work both for long gravity and short capillary waves, and are versatile enough to manipulate objects on the water surface. They can also be used for the controlled generation of Lagrangian coherent structures on the water surface, for example, to contain and stop the spread of surface pollutants21.

Methods

Wave generation.

Surface waves are generated by vertically oscillating plungers of different shapes (cylindrical, conical, pyramidal, and so on). Spatially localized time-periodic perturbations of the water surface generate waves propagating away from the plungers. The frequency of the plunger oscillations is varied in the range between 10 Hz, corresponding to gravity waves, and 200 Hz, corresponding to capillary waves. The dispersion relation at lower wave amplitudes is given by ω = (gk + αk3/ρ)1/2, where k is the wavenumber, g is the acceleration due to gravity, α is the surface tension and ρ is the fluid density. At higher amplitudes, the cross-wave instability modulates wavefronts in the transverse direction, destroying the two-dimensionality of the wave and breaking it into individual pulses, which then propagate away from the source. These propagating wave pulses oscillate vertically at half the driving frequency, f = f0/2, as expected for parametrically excited waves. The 2D wave fields shown in Fig. 1a, c are reconstructed using a diffusive light imaging technique. The results of Figs 1 and 2 are obtained using a cylindrical wave maker of diameter d = 25 mm and length L = 130 mm. For Figs 3 and 4 we use a 60° angle conical plunger, submerged to a diameter of 50 mm at the waterline. Experiments are performed in a rectangular container (1.5 × 0.5 m2) filled with water to a depth of 80 mm. The wave makers are driven by an electrodynamic shaker. The forcing is sinusoidal and monochromatic. The shaker frequency f0 = 20 Hz corresponds to a wavelength of λ = 12 mm. A vertically movable plunger is attached to the table of the electromagnetic shaker via the plunger frame. Linear light-emitting diode (LED) arrays on the sides of the transparent water tank illuminate surface particles whose motion is filmed from above using a high-resolution video camera.

Flow characterization.

The flow characteristics are measured using a diffusive light imaging technique, particle image velocimetry and particle tracking velocimetry techniques. We use diffusive light imaging to visualize the surface elevation of the wave field2,16. The fluid surface is illuminated by an LED panel placed underneath the transparent bottom of the container. A few per cent of milk added to water provides sufficient contrast to obtain a high-resolution reconstruction of the wave field. The absorption coefficient is measured before each experiment, allowing the calibration of the surface elevation with a vertical resolution of 20 μm. Floating imaging particles are used to visualize the fluid motion on the water surface2. Three-dimensional Lagrangian trajectories are obtained using a combination of a two-dimensional particle tracking velocimetry (PTV) technique and a subsequent evaluation of the local surface elevation along the trajectory. First, the horizontal (x–y) coordinates of each point on a trajectory are tracked using a nearest-neighbour algorithm22. Then, the particle elevations (z) are estimated as the mean of the wave elevation over a local window (500 μm radius) centred at the x–y particle coordinates at a given time. The 3D trajectories of the particle and the wave elevation are visualized using the 3D animation software Houdini (Side Effects Software).

Finite-time Lyapunov exponent.

The Lyapunov exponent measures the divergence rate between two adjacent trajectories. A finite-time Lyapunov exponent (FTLE) algorithm has been developed to compute the maximum Lyapunov exponents for the detection of Lagrangian coherent structures20,23. We use this method to locate the line of maximum divergence in the flow, as shown in Fig. 4f. The PTV velocity fields are interpolated on a refined spatial grid of 600 × 600 with a time step of Δt = 0.002 s. The particle trajectories are obtained by numerical integration using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta method. Each trajectory x(t, x0) starts at a position x0 at a fixed initial time t0. By numerical differentiation we compute the largest singular-value field λmax(t, t0, x0) of the deformation-gradient tensor field [∂ x(t, t0, x0)/∂ x0]T/[∂ x(t, t0, x0)/∂ x0]. The FTLE field can be obtained for initial positions x0 as

References

Francois, N., Xia, H., Punzmann, H. & Shats, M. Inverse energy cascade and emergence of large coherent vortices in turbulence driven by Faraday waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 194501 (2013).

Francois, N., Xia, H., Punzmann, H., Ramsden, S. & Shats, M. Three-dimensional fluid motion in Faraday waves: Creation of vorticity and generation of two-dimensional turbulence. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021021 (2014).

Stokes, G. G. On the theory of oscillatory waves. Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc. 8, 441–455 (1847). Reprinted in Stokes, G. G. Mathematical and Physical Papers Vol. 1, 197–229 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1880).

Falkovich, G. Fluid Mechanics: A Short Course for Physicists (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Constantin, A. On the deep water wave motion. J. Phys. A 34, 1405–1417 (2001).

Scales, J. A. & Snieder, R. What is a wave? Nature 401, 739–740 (1999).

Matioc, A-V. On particle trajectories in linear water waves. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 11, 4275–4284 (2010).

Longuet-Higgins, M. S. The trajectories of particles in steep, symmetric gravity waves. J. Fluid Mech. 94, 497–517 (1979).

Hogan, S. J. Particle trajectories in nonlinear capillary waves. J. Fluid Mech. 143, 243–252 (1984).

Benjamin, T. B. & Feir, J. E. The disintegration of wave trains on deep water. J. Fluid Mech. 27, 417–430 (1967).

Zakharov, V. E. Stability of periodic waves of finite amplitude on the surface of a deep fluid. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2, 190–194 (1968).

Saffman, P. G. & Yuen, H. C. A new type of three-dimensional deep-water waves of permanent form. J. Fluid Mech. 101, 797–808 (1980).

Meiron, D. I., Saffman, P. G. & Yuen, H. C. Calculation of steady three-dimensional deep-water waves. J . Fluid Mech. 124, 109–121 (1982).

Su, M-Y. Three-dimensional deep water waves. Part 1. Experimental measurements of skew and symmetric wave patterns. J. Fluid Mech. 124, 73–108 (1982).

Von Kameke, A., Huhn, F., Fernández-García, G., Muñuzuri, A. P. & Pérez-Muñuzuri, V. Double cascade turbulence and Richardson dispersion in a horizontal fluid flow induced by Faraday waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 074502 (2011).

Wright, W. B., Budakian, R., Pine, D. J. & Putterman, S. J. Imaging of intermittency in ripple-wave turbulence. Science 278, 1609–1612 (1997).

Xia, H., Shats, M. & Punzmann, H. Modulation instability and capillary wave turbulence. Europhys. Lett. 91, 14002 (2010).

Xia, H. & Shats, M. Propagating solitons generated by localized perturbations on the surface of deep water. Phys. Rev. E 85, 026313 (2012).

Sharp, D. H. An overview of Rayleigh–Taylor instability. Physica 12D, 3–18 (1984).

Haller, G. & Yuan, G. Lagrangian coherent structures and mixing in two-dimensional turbulence. Physica D 147, 352–370 (2000).

Peacock, T. & Haller, G. Lagrangian coherent structures: The hidden skeleton of fluid flows. Phys. Today 66(2), 41–47 (2013).

Crocker, J. C. & Grier, D. G. Methods of digital video microscopy for colloidal studies. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 179, 298–310 (1996).

Shadden, S. C., Lejien, F. & Marsden, J. E. Definition and properties of Lagrangian coherent structures from finite-time Lyapunov exponents in two-dimensional aperiodic flows. Physica D 212, 271–304 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP110101525). H.X. would like to acknowledge the support of the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE120100364). The authors thank K. Szewc for developing the code for the finite-time Lyapunov exponent analysis used to generate Fig. 4f, and M. Gwynneth for his help with experimental set-up. N.F. acknowledges the help of S. Ramsden of the National Computational Infrastructure, Vizlab, ANU with visualization of 3D flows and trajectories using the Houdini animation software. The research of G.F. was supported by the Minerva Foundation and the Binational Science Foundation (BSF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.P., N.F. and M.S. designed and performed the experiments; H.X., N.F., G.F. and H.P. analysed the data. M.S. and G.F. wrote the paper. All authors discussed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 1590 kb)

Supplementary Movie

Supplementary Movie 1 (MP4 20521 kb)

Supplementary Movie

Supplementary Movie 2 (MP4 7076 kb)

Supplementary Movie

Supplementary Movie 3 (MP4 9039 kb)

Supplementary Movie

Supplementary Movie 4 (MP4 7129 kb)

Supplementary Movie

Supplementary Movie 5 (MP4 2287 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Punzmann, H., Francois, N., Xia, H. et al. Generation and reversal of surface flows by propagating waves. Nature Phys 10, 658–663 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3041

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3041

This article is cited by

-

Optimal free-surface pumping by an undulating carpet

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Recurrent graph optimal transport for learning 3D flow motion in particle tracking

Nature Machine Intelligence (2023)

-

Bidirectional wave-propelled capillary spinners

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Manipulation of free-floating objects using Faraday flows and deep reinforcement learning

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Wave-based liquid-interface metamaterials

Nature Communications (2017)