Abstract

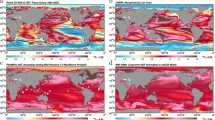

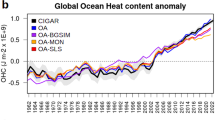

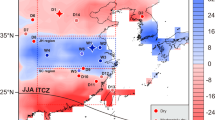

The oceans mediate the response of global climate to natural and anthropogenic forcings. Yet for the past 2,000 years — a key interval for understanding the present and future climate response to these forcings — global sea surface temperature changes and the underlying driving mechanisms are poorly constrained. Here we present a global synthesis of sea surface temperatures for the Common Era (ce) derived from 57 individual marine reconstructions that meet strict quality control criteria. We observe a cooling trend from 1 to 1800 ce that is robust against explicit tests for potential biases in the reconstructions. Between 801 and 1800 ce, the surface cooling trend is qualitatively consistent with an independent synthesis of terrestrial temperature reconstructions, and with a sea surface temperature composite derived from an ensemble of climate model simulations using best estimates of past external radiative forcings. Climate simulations using single and cumulative forcings suggest that the ocean surface cooling trend from 801 to 1800 ce is not primarily a response to orbital forcing but arises from a high frequency of explosive volcanism. Our results show that repeated clusters of volcanic eruptions can induce a net negative radiative forcing that results in a centennial and global scale cooling trend via a decline in mixed-layer oceanic heat content.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Moberg, A., Sonechkin, D. M., Holmgren, K., Datsenko, N. M. & Karlen, W. Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low- and high-resolution proxy data. Nature 433, 613–617 (2005).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Jones, P. D. et al. High-resolution palaeoclimatology of the last millennium: A review of current status and future prospects. Holocene 19, 3–49 (2009).

Braconnot, P. et al. Evaluation of climate models using palaeoclimatic data. Nature Clim. Change 2, 417–424 (2012).

Marcott, S. A., Shakun, J. D., Clark, P. U. & Mix, A. C. A reconstruction of regional and global temperature for the past 11,300 years. Science 339, 1198–1201 (2013).

Schmidt, G. A. et al. Climate forcing reconstructions for use in PMIP simulations of the last millennium (v1.1). Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 185–191 (2012).

PAGES 2k Consortium Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia. Nature Geosci. 6, 339–346 (2013).

Gill, A. E. Atmosphere–Ocean Dynamics Vol. 30 (International Geophysics Series, Academic, 1982).

Balmaseda, M. A., Trenberth, K. E. & Källén, E. Distinctive climate signals in reanalysis of global ocean heat content. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1754–1759 (2013).

Rhein, M. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 255–315 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Kennedy, J. J. A review of uncertainty in in situ measurements and data sets of sea surface temperature. Rev. Geophys. 52, 1–32 (2014).

Lee, T. C. K., Zwiers, F. W. & Tsao, M. Evaluation of proxy-based millennial reconstruction methods. Clim. Dynam. 31, 263–281 (2008).

Mann, M. E. et al. Proxy-based reconstructions of hemispheric and global surface temperature variations over the past two millennia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 13252–13257 (2008).

Evans, M. N., Tolwinski-Ward, S. E., Thompson, D. M. & Anchukaitis, K. J. Applications of proxy system modeling in high resolution paleoclimatology. Quat. Sci. Rev. 76, 16–28 (2013).

Lohmann, G., Pfeiffer, M., Laepple, T., Leduc, G. & Kim, J. H. A model–data comparison of the Holocene global sea surface temperature evolution. Clim. Past 9, 1807–1839 (2013).

Laepple, T. & Huybers, P. Global and regional variability in marine surface temperatures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2528–2534 (2014).

Lamb, H. H. The early medieval warm epoch and its sequel. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1, 13–37 (1965).

Neukom, R. et al. Inter-hemispheric temperature variability over the past millennium. Nature Clim. Change 4, 362–367 (2014).

Kaplan, A. et al. Analyses of global sea surface temperature 1856–1991. J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans 103, 18567–18589 (1998).

Allan, R. et al. The international Atmospheric Circulation Reconstructions over the Earth (ACRE) initiative. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 92, 1421–1425 (2011).

Emile-Geay, J., Cobb, K. M., Mann, M. E. & Wittenberg, A. T. Estimating central equatorial Pacific SST variability over the past millennium. Part I: Methodology and validation. J. Climate 26, 2302–2328 (2013).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Tropical sea-surface temperatures for the past four centuries reconstructed from coral archives. Paleoceanography 30, 226–252 (2015).

Evans, M. N., Kaplan, A. & Cane, M. A. Pacific sea surface temperature field reconstruction from coral δ18O data using reduced space objective analysis. Paleoceanography 17, 1007 (2002).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 409–415 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

McKay, N. P. & Kaufman, D. S. An extended Arctic proxy temperature database for the past 2,000 years. Sci. Data 1, 140026 (2014).

Phipps, S. J. et al. Paleoclimate data–model comparison and the role of climate forcings over the past 1500 years. J. Climate 26, 6915–6936 (2013).

Crespin, E., Goosse, H., Fichefet, T., Mairesse, A. & Sallaz-Damaz, Y. Arctic climate over the past millennium: Annual and seasonal responses to external forcings. Holocene 23, 321–329 (2013).

Delaygue, G. & Bard, E. An Antarctic view of Beryllium-10 and solar activity for the past millennium. Clim. Dynam. 36, 2201–2218 (2011).

Schurer, A. P., Tett, S. F. B. & Hegerl, G. C. Small influence of solar variability on climate over the past millennium. Nature Geosci. 7, 104–108 (2014).

Bard, E. & Frank, M. Climate change and solar variability: What's new under the sun? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 248, 1–14 (2006).

Rind, D., Lean, J., Lerner, J., Lonergan, P. & Leboissitier, A. Exploring the stratospheric/tropospheric response to solar forcing. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 113, D24103 (2008).

Berger, A. L. Long-term variations of daily insolation and Quaternary climatic changes. J. Atmos. Sci. 35, 2362–2367 (1978).

Hays, J. D., Imbrie, J. & Shackleton, N. J. Variations in the Earth's orbit: Pacemaker of the Ice Ages. Science 194, 1121–1132 (1976).

Esper, J. et al. Orbital forcing of tree-ring data. Nature Clim. Change 2, 862–866 (2012).

Kaufman, D. S. et al. Recent warming reverses long-term Arctic cooling. Science 325, 1236–1239 (2009).

Brovkin, V. et al. Biogeophysical effects of historical land cover changes simulated by six Earth system models of intermediate complexity. Clim. Dynam. 26, 587–600 (2006).

Goosse, H. et al. The origin of the European “Medieval Warm Period”. Clim. Past 2, 99–113 (2006).

de Noblet-Ducoudré, N. et al. Determining robust impacts of land-use-induced land cover changes on surface climate over North America and Eurasia: Results from the first set of LUCID experiments. J. Climate 25, 3261–3281 (2012).

He, F. et al. Simulating global and local surface temperature changes due to Holocene anthropogenic land cover change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 623–631 (2014).

Hansen, J., Lacis, A., Ruedy, R. & Sato, M. Potential climate impact of Mount Pinatubo eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 19, 215–218 (1992).

Robock, A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000).

Stenchikov, G. et al. Volcanic signals in oceans. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 114, D16104 (2009).

Miller, G. H. et al. Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L02708 (2012).

Plummer, C. T. et al. An independently dated 2000-yr volcanic record from Law Dome, East Antarctica, including a new perspective on the dating of the 1450s CE eruption of Kuwae, Vanuatu. Clim. Past 8, 1929–1940 (2012).

Sigl, M. et al. Insights from Antarctica on volcanic forcing during the Common Era. Nature Clim. Change 4, 693–697 (2014).

Goosse, H., Barriat, P. Y., Lefebvre, W., Loutre, M. F. & Zunz, V. Introduction to Climate Dynamics and Climate Modeling (Université catholique de Louvain, 2015); http://www.climate.be/textbook

Crowley, T. J. Causes of climate change over the past 1000 years. Science 289, 270–277 (2000).

Zhong, Y. et al. Centennial-scale climate change from decadally-paced explosive volcanism: A coupled sea ice-ocean mechanism. Clim. Dynam. 37, 2373–2387 (2011).

Mignot, J., Khodri, M., Frankignoul, C. & Servonnat, J. Volcanic impact on the Atlantic Ocean over the last millennium. Clim. Past 7, 1439–1455 (2011).

Ding, Y. et al. Ocean response to volcanic eruptions in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 simulations. J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans 119, 5622–5637 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the many scientists who made their published data sets available via public data repositories. T. Kiefer, L. von Gunten and C. Telepski from the IGBP PAGES-IPO provided organizational and logistical support. V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Giry, S. P. Bryan, S. Stevenson, D. Colombaroli, B. Horton, J. Tierney and the Ocean2k HR Working Group are thanked for early input to the project design and methodology. G. Lohmann assisted with model output. A. Mairesse assisted with model figures. L. Skinner and D. Reynolds are thanked for discussions on age models. We are grateful to the 75 volunteers who constructed the Ocean2k metadatabase (see Supplementary Information for full list of names). We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme's Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the climate modelling groups (listed in Supplementary Table S4) for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP, the US Department of Energy's Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provides coordinating support and led development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. We acknowledge support from PAGES, a core project of IGBP financially supported by the US and Swiss National Science Foundations (NSFs) and NOAA; Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project grant DP1092945 (H.V.M., S.J.P.), ARC Future Fellowship FT140100286 grant (H.V.M.), AINSE Fellowship grant (H.V.M.) and the research contributes to ARC Australian Laureate Fellowship FL120100050; US NSF awards NSF/ATM09-02794 (M.N.E.) and NSF/ATM0902715 (M.N.E), and Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund grant 11-UOA-027 (M.N.E.); F.R.S-FNRS (Belgium; H.G.); French National Research Agency (ANR) under ISOBIOCLIM grant (G.L.); European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number 243908, Past4Future 'Climate change — Learning from the past climate' contribution no. 81 (H.G., B.M., P.G.M., M.-S.S.); CSIC-Ramón y Cajal post-doctoral programme RYC-2013-14073 (B.M.), Clare Hall College, Cambridge, Shackleton Fellowship (B.M.) and Red CONSOLIDER GRACCIE CTM2014-59111-REDC (B.M.); US Geological Survey's Climate and Land Use Change Research and Development Program and the Volcano Science Center (J.A.A.); Ralph E. Hall Endowed Award for Innovative Research (D.W.O.); Danish Council for Independent Research Natural Science OCEANHEAT project 12-126709/FNU (M.-S.S.); LEFE/INSU/NAIV project (M.-A.S.); NSF of China grant 41273083 (K.S.) and Shanhai Fund grant 2013SH012 (K.S.); UTIG Ewing-Worzel Fellowship (K.T.); Swedish Research Council grant 621-2011-5090 (H.L.F.); and from a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship for Career Development (V.E.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N.E., H.V.M., D.W.O., H.G., G.L. and B.M. designed the project with input from J.A.A., M.-S.S., M.-A.S., K.S. and V.E.; H.V.M. and G.L. led the synthesis. H.V.M. and B.M. collated and evaluated the reconstructions, and managed the data with assistance from J.A.A.; M.N.E. led the analysis with important contributions from H.G., J.A.A., B.M., G.L., S.J.P., H.V.M., D.W.O., P.G.M., M.-S.S. and M.-A.S.; H.G. and S.J.P. collated, managed and analysed the model simulations with input from M.N.E., G.L. and H.V.M.; H.V.M. led the writing with the assistance of M.N.E., H.G., G.L., B.M., J.A.A., P.G.M., D.W.O., M.-S.S., M.-A.S., S.J.P., K.S., K.T., H.L.F and V.E.; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information (PDF 9213 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McGregor, H., Evans, M., Goosse, H. et al. Robust global ocean cooling trend for the pre-industrial Common Era. Nature Geosci 8, 671–677 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2510

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2510

This article is cited by

-

ModE-RA: a global monthly paleo-reanalysis of the modern era 1421 to 2008

Scientific Data (2024)

-

Revisiting the Holocene global temperature conundrum

Nature (2023)

-

Marine records reveal multiple phases of Toba’s last volcanic activity

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Rapid 20th century warming reverses 900-year cooling in the Gulf of Maine

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

-

Timing of emergence of modern rates of sea-level rise by 1863

Nature Communications (2022)