Abstract

The notion of species as reproductively isolated units related through a bifurcating tree implies that gene trees should generally agree with the species tree and that sister taxa should not share polymorphisms unless they diverged recently and should be equally closely related to outgroups. It is now possible to evaluate this model systematically. We sequenced multiple individuals from 27 described taxa representing the entire Arabidopsis genus. Cluster analysis identified seven groups, corresponding to described species that capture the structure of the genus. However, at the level of gene trees, only the separation of Arabidopsis thaliana from the remaining species was universally supported, and, overall, the amount of shared polymorphism demonstrated that reproductive isolation was considerably more recent than the estimated divergence times. We uncovered multiple cases of past gene flow that contradict a bifurcating species tree. Finally, we showed that the pattern of divergence differs between gene ontologies, suggesting a role for selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The genus Arabidopsis has been proposed to consist of as many as 26 taxa in addition to the model plant A. thaliana1. To clarify relationships within this important genus, we resequenced 94 individuals, covering all taxa, sampled throughout their geographic range (Table 1, Supplementary Data Set 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Because A. thaliana was known to be most distantly related to the other taxa and should thus be equally related to all of them under a bifurcating speciation model, the reads were mapped to the A. thaliana reference genome. On average, 43% were mapped, covering about 66% of the genome (Supplementary Data Set 1). To produce a high-quality data set for between-species comparisons across the genus, we focused on genic regions, requiring that at least half of all exons be covered in each individual, and excluded genes that showed evidence of duplication. The resulting data are thus biased toward conserved exons, as well as with respect to A. thaliana. In total, 9,119 genes fulfilled our criteria across the entire sample, comprising genus-wide alignments for 25 Mb of the genome. The data were analyzed together with published SNPs from 337 A. thaliana lines2,3,4. In total the alignment contains 7.5 million SNPs, 6.6 million of which are biallelic.

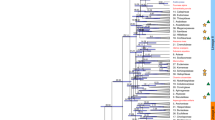

Clustering on the basis of genome-wide polymorphism revealed four major groups, corresponding to the widely distributed species A. thaliana, A. halleri, A. lyrata and A. arenosa, and three minor groups, corresponding to the geographically limited A. croatica, A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). This is in broad agreement with previous results1. In addition, there are the two well-known allotetraploid species, A. suecica and A. kamchatica, hybrids between A. arenosa and A. thaliana and between A. lyrata and A. halleri, respectively5,6,7, and there is also clear evidence for the previously described admixture between tetraploid A. lyrata ssp. petraea and A. arenosa ssp. borbasii8.

The genus Arabidopsis can be grouped into four common species (A. thaliana, A. halleri, A. lyrata and A. arenosa), three species with limited geographic distribution (A. croatica, A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana) and two allotetraploid species (A. suecica and A. kamchatica). Center, neighbor-joining tree based on genetic distance between all analyzed individuals including ten A. thaliana accessions and using Capsella rubella as an outgroup. Allotetraploid individuals were each treated as two independent individuals based on previous mapping to parental genomes (Online Methods). Colored bars show the results of clustering using ADMIXTURE47 (inner circle K = 5; outer circle, K = 8; see Supplementary Fig. 2 for cross-validation results). Tetraploid individuals from the A. lyrata and A. arenosa clades that were previously shown to be the product of admixture8 are marked with black lines outside the circles.

The divergence among these species is highly variable. At the level of individual gene trees (Supplementary Fig. 3), 100% supported the monophyly of A. thaliana—as expected, given that this species is estimated to have diverged from the rest of the genus at least 6 million years ago (Myr)9 (Supplementary Fig. 4) and is reproductively isolated as a consequence of a chromosome number of 5 rather than 8 (Table 1). The separation of A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana from the remaining diploids is also strong (63% of gene trees supported this split), whereas the remaining species, at least some of which can be crossed experimentally10,11, are much more closely related.

To gain further insight into the relationships among the species, we searched for identical-by-descent (IBD) haplotypes using BEAGLE12 (Fig. 2). Only 49 such haplotypes were detected in comparisons between species, compared to 14,600 within the outcrossing species (haplotype sharing in the selfing A. thaliana is much more extensive, as expected)13. The haplotypes shared between species were very short (median = 2.0 kb, maximum = 3.4 kb), suggesting gene flow occurring on the order of 20,000 generations ago rather than more recently (Online Methods). Much longer shared haplotypes were found within the outcrossing species (median = 2.3 kb, maximum = 16.3 kb), although most haplotypes shared within these species were also short (Supplementary Fig. 5), probably owing to the patchiness of data that result from cross-species alignments.

Because the BEAGLE algorithm requires phased data, only diploid individuals were used. Heatmap colors represent the total length of IBD blocks for each pairwise comparison (Online Methods).

Although the IBD analysis did not reveal conclusive evidence for gene flow, we used the results to guide further analyses. Specifically, we used the presence of between-species IBD blocks (Fig. 2) to identify probable cases of gene flow and then further examined these using the ABBA-BABA test14,15. This test uses the distribution of derived alleles to determine whether one of two sister taxa is closer to an outgroup than the other (thus violating a bifurcating species tree). We found several such cases. For example, subarctic A. lyrata was more closely related to A. halleri from East Asia than to A. halleri from continental Europe (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 6a–d), suggesting ancient admixture in East Asia between A. lyrata and A. halleri. Gene flow between these species was also supported by the incongruence between the chloroplast tree and the species tree (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), and the allopolyploid A. kamchatica originated in East Asia through hybridization between A. lyrata and A. halleri7. Similarly, the common ancestor of A. pedemontana and A. cebennensis was more closely related to A. halleri than to A. lyrata or A. arenosa (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Consistent with hybridization between these species, we observed shared haplotypes between only the geographically closest samples of A. pedemontana and A. halleri (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 7b).

(a) Geographic distribution of the A. halleri (small charts) and A. lyrata (large charts) samples used. The colors of the charts correspond to the ADMIXTURE results with K = 8 in Figure 1. We divided A. halleri into eastern (orange area) and western lineages and A. lyrata into northern (blue area) and southern lineages. (b) Northern A. lyrata (lN) are closer to eastern A. halleri (hE) than to western A. halleri (hW). Plots show the distribution of D statistics resulting from testing different individuals from each region; the significance of the D statistics for each test can be assessed using previously published methods14,48 (Supplementary Fig. 6a–d and Online Methods). All between-population comparisons discussed are significant, i.e., hE was closer to A. lyrata than was hW (two-sided Wilcoxon test; P = 9.5 × 10−190, blue vs. green plot), and lN was closer to hE than was southern A. lyrata (lS) (P = 8.2 × 10−11, light green vs. dark green plot). **P < 0.01. (c) A. thaliana is closest to A. lyrata and most distant from A. arenosa. The Z-scores corresponding to the D statistics for each test are shown in Supplementary Figure 6e–j.

We did not detect any shared IBD blocks between A. thaliana and other species in the genus. However, the ABBA-BABA test shows that A. thaliana is closer to A. lyrata than to A. arenosa (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 6e–j). This contradicts a species tree in which the rest of the genus would be monophyletic with respect to A. thaliana and is notable given that the average sequence divergence between the common outcrossing species is less than half of that between these species and A. thaliana (Supplementary Table 1). Thus the highly diverged model plant A. thaliana appears to have become reproductively isolated from the outcrossing species considerably more recently than the estimated divergence time of 6 Myr9 (Supplementary Fig. 3). This has important implications for within-species polymorphism data. For example, the well-established pattern of local deep sequence divergence within A. thaliana16 may well reflect ancient admixture, and the dramatic changes in genome structure that distinguish this species from the rest of the genus may have occurred even more rapidly than previously believed17, perhaps in conjunction with the transition to selfing18,19.

Significant ABBA-BABA results may reflect population subdivision in the ancestral species as well as gene flow14,20. Thus the fact that fossil Neanderthals share more alleles with modern non-Africans than with modern Africans may not necessarily reflect admixture between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans outside Africa but could also indicate that both Neanderthals and the modern humans that left Africa came from the same African subpopulation or isolated region15. However, for this to have occurred, the ancient African subdivision would have had to persist for a very long time while still allowing sufficient gene flow for modern humans to be most closely related at most loci (and evolve into anatomically modern humans). Admixture thus seems a more likely explanation.

Analogously, the greater number of shared alleles between A. thaliana and A. lyrata than between A. thaliana and A. halleri or A. arenosa could be due to ancient population subdivision, with the same subpopulation or region giving rise to A. thaliana and A. lyrata. However, the argument against the likelihood of ancient subdivision in humans is even stronger in Arabidopsis, because the species are so highly diverged. Whereas average coalescence times in modern humans are greater than the supposed split from Neanderthals, the average coalescence times between the common outcrossing Arabidopsis species is less than half the divergence between these species and A. thaliana.

Despite the evidence for ancient gene flow, the modern species are clearly distinct. Allele frequencies for shared polymorphisms were uncorrelated (Fig. 4), and Fst was very high (given the high levels of within-species polymorphism21), ranging from 0.71 to 0.78 for comparisons involving A. thaliana, ranging 0.2–0.4 for comparisons among the other three common species (Supplementary Table 1). However, even the highly diverged A. thaliana shares polymorphisms with the other species (for example, more than 20,000 synonymous SNPs with A. lyrata). Many of these must be due to mutation independently generating the same polymorphism in both species, but they could also be ancestral polymorphisms, maintained either by balancing selection22,23 or by chance (the latter is possible only if divergence times were more recent than estimated; see Online Methods).

To investigate this further, we focused on SNPs that segregate in all four common species. Using conservative filtering to avoid paralogous SNPs caused by cryptic duplications, we observed 3,818 SNPs in 2,365 genes. These genes show substantially higher values of Tajima's D statistic24 than random genes (Supplementary Fig. 8), as expected for ancestral polymorphisms, regardless of whether they are maintained by selection.

To eliminate any shared polymorphism due to repeated mutations, we refined this set further by considering only shared haplotypes with at least two shared SNPs. Such haplotypes are unlikely to have arisen independently25. Specifically, we selected genes with shared haplotypes such that a pair of SNPs shared across species was in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.3) in A. thaliana and in at least two of the three other common species. Moreover, we required that at least one of the shared SNPs was nonsynonymous. Using these criteria, we ended up with 129 genes containing 340 shared sites (Supplementary Data Set 2). These genes showed an even stronger increase in Tajima's D value relative to background (Supplementary Fig. 8) and were significantly (FDR-corrected P = 0.006; Online Methods) enriched for genes involved in response to virus, suggesting that selection may indeed have contributed to maintaining some of the ancestral polymorphisms. We identified a total of four virus-response genes with haplotypes shared across all four species: CYCT1;4 (TAIR locus AT4G19600), which is involved in transcriptional activation of viral genes; GRIK1 (TAIR locus AT3G45240), which has a role in the metabolic regulation of virus-infected cells26,27; NIG (TAIR locus AT4G13350), which is involved in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of viral proteins28; and WAK1 (TAIR locus AT1G21250), which activates an immunity response to damaged cell walls29.

If selection had a role in determining which genes share polymorphism across species, it may also have influenced which genes do not. Although our data are heavily biased toward genes that are conserved across the genus, we searched for genes that may have contributed to the adaptive divergence between species, primarily relying on high Fst values in combination with low polymorphism and Tajima's D values. We focused on identifying gene categories that appeared to be overrepresented among divergent genes in particular species. Several such categories were found (Supplementary Table 2). For example, genes divergent in A. halleri were overrepresented in the 'heavy metal–associated domain' category, consistent with metal hyperaccumulation in A. halleri30,31. Less obviously, genes divergent in A. lyrata were overrepresented in the 'circadian rhythm' category, perhaps reflecting the wide latitudinal distribution of this species and adaptation to different day lengths. Indeed, a recent selective sweep in phytochromes has been described in A. lyrata populations32. Finally, genes identified in the morphologically highly divergent A. pedemontana and A. cebennensis were overrepresented in the 'organ morphogenesis' and 'tissue development' categories.

In conclusion, the current species of the genus Arabidopsis, which are clearly identifiable with either morphological or polymorphism data (Fig. 1), do not have a tree-like relationship. Gene trees and species trees may disagree because of 'incomplete lineage sorting', but this discrepancy is simply a consequence of random coalescence events between closely related species; it may make species trees difficult to infer, but it does not contradict their existence33. The results we present here do, and the apparent pervasiveness of gene flow suggests that it is not just a case of introgression leading to minor inconsistencies. Rather, we would argue that speciation in this genus is a protracted process involving selection and long periods of partial isolation between multiple incipient species, perhaps as a consequence of the multiple glaciations that have characterized the Quaternary Period. A bifurcating species tree describes neither the data nor the process that gave rise to the data. Evidence for genome-wide contradictions between gene trees and species trees is rapidly accumulating in a wide range of species15,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, raising the question of whether this should lead to a reevaluation of the utility of the tree as model for speciation45,46. We think it should, but time will tell.

Methods

DNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing.

Whole genomic DNA was extracted from fresh, silica dried or herbarium voucher leaf material either with the CTAB protocol49 or Invisorb Spin Plant Mini Kit or Qiagen DNeasy plant kit (Supplementary Data Set 1). The CTAB protocol was used with the following modifications: DNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol twice and dissolved in 100 μl TE buffer supplemented with 2 units RNase A. Total genomic DNA libraries were prepared using either NEXTflex DNA Sequencing Kit or NEBNext DNA Library Prep Kit or TruSeq DNA Sample Prep Kit. Sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq 2000 in 100 bp paired-end mode with a library insert size of 200–400 bp (Supplementary Data Set 1).

We performed correction of raw reads for the A. halleri ssp. halleri 3 sample (Supplementary Data Set 1). The ErrorCorrectReads.pl module of ALLPATHS-LG version 44837 was used for correction of raw reads (34.0 million reads). PHRED_ENCODING was set to 64, and the other parameters were set to default according to the ALLPATHS-LG manual. In total, 24.9 million corrected reads were used in downstream data analyses.

Raw reads were uploaded to NCBI SRA (numbers of BioProjects and BioSamples are available in Supplementary Data Set 1). Chloroplast assemblies were uploaded to ENA (Supplementary Data Set 1).

Read mapping and variants discovery.

We mapped reads to A. thaliana (TAIR10) reference genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm from BWA50 (version 0.7.4) with an increased penalty for unpaired read pairs to 15, then we removed duplicated reads with Samtools51 (version 0.1.18) rmdup function and performed local realignment with Genome Analysis Toolkit52,53 (GATK, version 2.5.2) IndelRealigner. After filtering for uniquely and primary aligned reads, we calculated coverage distribution using GATK Pileup and chose intervals with coverage between the third and ninety-seventh percentiles for further analysis. SNPs and short indels were called with GATK UnifiedGenotyper with default quality thresholds. Diploid samples were phased using GATK ReadBackedPhasing. Called SNPs were annotated with SnpEff software54. We also included 337 A. thaliana accessions from already published data sets2,3,4 and used mapping and SNP calling for these samples from the 1001 Genomes Project55.

We first separated allopolyploid samples raw data according to the parental genomes and then included them into the main pipeline for diploid and tetraploid individuals described above. A. suecica reads were mapped to A. thaliana (TAIR10) and A. lyrata17 (version 1.0) references simultaneously using the same parameters and software. After the realignment step, reads were filtered for primary and uniquely aligned reads in proper pairs (samtools flags −F 256 −f 3 −q 10) and then split according to the scaffolds. Reads mapped to Chr1–5 of A. thaliana and scaffolds 1–8 of A. lyrata reference parts were then mapped separately to the A. thaliana reference. A. kamchatica reads were mapped to two parental species genome (A. halleri56 and A. lyrata) and separated into two groups using the read classification method HomeoRoq56, and we treated each A. kamchatica sample as two different diploid individuals.

The structure of the genus Arabidopsis.

Population structure analysis was performed using all the samples of A. thaliana relatives, 10 A. thaliana accessions from different geographical locations and C. rubella as an outgroup. We focused on genic regions where at least half of the total exon length was covered in each individual analyzed. Then we calculated copy number for those genes in each individual on the basis of total exon coverage depth normalized by mean coverage depth and filtered for genes with copy number between 0.4 and 1.6 in all individuals. 9,119 genes satisfied these criteria.

A neighbor-joining tree was built with R package APE57 from the genetic distance matrix generated from the 281,305 biallelic SNP calls that had no missing data. Genealogies of individual genes were generated using the same approach. Support values for tree splits were calculated by SumTrees program from DendroPy package58 using the percentage of the trees in which a particular split is found as a degree of support. Maximum likelihoods of individual ancestries were estimated with ADMIXTURE47 for the same genes, allowing for missing data. In order to include autotetraploid samples in ancestry assignment, we randomly chose two alleles for each site. We chose two local minima of cross-validation errors of ancestral populations assignment (K = 5 and K = 8) for subsequent analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We performed identity-by-descent (IBD) blocks analysis for diploid Arabidopsis lineages using the algorithm from BEAGLE12 (version 4.0) with the following parameters: window = 100,000; overlap = 10,000; ibdtrim = 100; ibdlod = 10. The number of markers per window, overlap between windows, and number of trimmed markers were roughly doubled compared to the default parameters, which were optimized for human SNP array data; input data in our case are more dense in number of SNPs per cM. We expect no IBD blocks between C. rubella and Arabidopsis, and this was satisfied using a minimum LOD score of 10.

Very roughly, the expected length of a shared haplotype is 1/(rt), where r is the recombination rate per base pair, and t is the time of separation59. Thus, assuming r = 10−8, we would expect to see shared haplotypes of length 2 kb if t = 20,000 generations.

ABBA-BABA analysis was performed with the ANGSD toolbox60 (analysis of next-generation sequencing, version 0.579) using C. rubella as an outgroup in all comparisons and genotype information only at coding regions from the 9,119 genes that passed copy number filtering. A. halleri lineages were split into eastern (A. halleri E) and western (A. halleri W) groups according to their geographical origin; A. lyrata lineages were split into northern (A. lyrata N) and southern (A. lyrata S) groups according to their geographical origin and ADMIXTURE assignment at K = 8 (Fig. 4a). We ran ABBA-BABA analysis and calculated D statistics for all combinations of A. halleri and A. lyrata lineages (Fig. 4b). D statistics for analysis including A. thaliana were calculated as (ABBA – BABA) / (ABBA + BABA) for biallelic sites between the reference (TAIR10, Col-0 accession) and diploid A. thaliana relatives (Fig. 4c). To determine the significance of the D statistics we calculated Z scores for 1-Mb blocks using jackKnife.R script from the ANGSD toolbox60. Note that all the species were mapped to A. thaliana reference genome, which can be considered an outgroup for the other Arabidopsis species. This approach makes mapping bias unlikely when considering admixture between A. thaliana and the remaining species (whereas mapping to A. lyrata would greatly favor A. lyrata samples over those from A. arenosa and A. halleri).

Arabidopsis genus structure based on chloroplast DNA.

Complete chloroplast genomes were assembled in CLC Genomics Workbench version 6.0.4 (CLC bio). Reads were trimmed for adapters as well as a minimum quality of 0.001 (Phred score 30) and a minimum length of 50 bp. Paired reads were assembled using the legacy version of the CLC de novo algorithm with length fraction 0.9, similarity 0.9 and appropriate distance settings. Contigs belonging to the chloroplast were identified using blastn and aligned manually to the closest related published complete chloroplast sequence (A. thaliana for Arabidopsis species, Capsella bursa-pastoris for C. rubella and Camelina sativa) using PhyDE version 0.9971. A preliminary pseudo-reference was created by filling gaps between nonoverlapping contigs from the reference sequence. The complete chloroplast genome was obtained by repeated cycles of mapping back to the pseudo-reference and variant detection in CLC (minimum coverage 1, variant probability 0.1) as well as manually. Misalignments and mismatches were adjusted at every step.

Complete chloroplast sequences were aligned using MAFFT61 version 7.017 implemented in Geneious version 7.1.7 (Biomatters Ltd.). The FFT-NS-ix1000 algorithm was used, with the 200PAM / k = 2 scoring matrix, a gap open penalty of 1.53 and an offset value of 0.123. The second copy of the inverted repeat was excluded. Using the annotation of the A. thaliana chloroplast genome, the complete alignment was divided into 263 parts, corresponding to exons, introns and intergenic regions. Indels and nonalignable regions were excluded from the alignments using Gblocks62 version 0.91b, with minimum block length of 2 bp.

PartitionFinder63,64 version 1.1.1 was used to partition the data set into subsets of genes evolving with a similar rate and under the same nucleotide substitution model, thus accounting for rate heterogeneity among genes. Only models implemented in BEAST were tested, with BIC used for model selection in a 'greedy' search and unlinked branch lengths. The best partitioning scheme comprised two subsets, one (55,892 bp) evolving under the generalized time-reversible model of evolution with gamma model of rate heterogeneity and invariant sites (GTR+I+Γ) and the other (62,184 bp) under the GTR+I model.

Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed with maximum likelihood (ML) using RAxML65 version 8.1.16 based on the two partitioned sequence alignments described above. A rapid bootstrap analysis and search for the best-scoring ML tree was conducted with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The partitioned data set with per-partition estimation of branch lengths was used with GTR+I+Γ as substitution model and the clade of C. rubella, C. bursa-pastoris and Camelina sativa was set as an outgroup. The ML tree was used as a starting tree for divergence time estimation after it was made ultrametric with node ages to fit constraints using the R package APE57 version 3.1–4. Divergence time was estimated using the software BEAST66 version 1.7. The same partitioned alignments as for ML analysis were used, with their respective best models as substitution models. Site and clock models were set to unlinked, but a linked partition tree was used with tree prior birth–death incomplete sampling67. An uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock with estimated rates was used to account for rate heterogeneity between sites68. Owing to the lack of fossils from the genus Arabidopsis or the Brassicaceae family we used secondary calibration for divergence time estimation. Three calibration points were extracted from Hohmann et al.9: The age of the outgroup (split between the genera Camelina and Capsella) was set to 7.3572 Myr; the crown age of the genus Arabidopsis was set to 5.9685 Myr, and the root height (split between outgroup and genus Arabidopsis) was set to 8.1627 Myr. Normal distributions with a s.d. = 1.0 fit the 95% confidence intervals from Hohmann et al.9 and were thus used for all three calibration points. An additional constraint was set on the root height by truncation to 4–12 Myr.

We ran two independent MCMC runs with 5 × 108 generations each and sampling parameters every 5 × 104 generations. LogCombiner66 version 1.7.5 was used to combine trees from the two runs and the first 5 × 107 generations of each run were discarded as burn-in. The resulting 18,000 trees were combined to a maximum clade credibility tree in TreeAnnotator66 version 1.7.5 and visualized in FigTree66 version 1.4.1.

Neutral expectations for allele sharing.

Consider the number of shared polymorphism expected under the standard coalescent model. A necessary condition for trans-specific polymorphism is that two lineages survive back to the species split in both sister species. The probability of this is exp[–tsplit/(2Ne)] independently in each species, where tsplit is the number of generations ago the two species became isolated, and Ne is the effective population size, which may differ between the two species69. The expected pairwise coalescence time is E(T2) = 2Ne generations within each species, and E(T2) = 2Ne + tsplit generations between species, where Ne in the latter equation is that of the ancestral species. In what follows, we will assume that Ne of the ancestral species equaled the larger of the Ne of the descendant species. Simple moments estimators for all relevant parameters can be obtained by noting that the expectation of the pairwise sequence divergence d is proportional to E(T2). We can thus obtain an upper bound for the probability of a trans-specific polymorphism as

where dA is the estimated pairwise sequence divergence (nucleotide diversity) within species A, dB the same for species B, and dAB is the estimated pairwise sequence divergence between species.

For example, the per-site probability of a trans-specific polymorphism under neutrality between A. thaliana and A. lyrata is less than e−(11.57–3.04)/0.69 × e−(11.6–3.04)/3.04 = 2.5 × 10−7. This is conservative, because it ignores the probability of the right order of coalescences in the ancestral species. The pairwise sequence divergence at aligned fourfold degenerate sites was used for the calculation. Thus, if we were to choose two alleles at random from each these two species, we would expect <1 out of the 2,909,657 fourfold degenerate sites to be trans-specific by chance. In the actual data we observed 599, and we conclude that either there was gene flow more recently than what is implied by the high divergence under the simple model of splitting or polymorphisms were maintained by selection.

Shared polymorphisms between common Arabidopsis species.

We applied the same criteria to choose genes for the analysis of shared variation between major Arabidopsis clades, restricting it to 80 A. thaliana relatives analyzed and excluding A. thaliana from filtering genes pipeline, which gave us 15,454 genes that passed copy number filtering. Joint allele frequency spectra were calculated for biallelic sites in two clades, unfolded using C. rubella as an outgroup and plotted with dadi70.

Fst estimates for pairwise common species (A. thaliana, A. halleri, A. lyrata, A. arenosa), comparisons were calculated at biallelic synonymous SNPs (Supplementary Table 1) as (Htotal – Hsubsp) / Htotal, where Htotal is heterozygosity in total population (for example, A. thaliana and A. halleri taken together as one population), Hsubsp is average of heterozygosities in subpopulations (for example, average of A. thaliana and A. halleri heterozygosities). Heterozygosity is calculated as 2pq, where p and q are derived and ancestral allele frequencies, respectively.

We searched for SNPs segregating in all four common Arabidopsis species. Even though we filtered out potential duplicated genes on the basis of coverage before calling variants, we noticed that some of the shared sites show: (i) only heterozygous genotypes (Aa) or (ii) heterozygous and only one of the homozygous genotypes (Aa and AA or Aa and aa) among diploid A. thaliana relatives, which can be explained by the presence of a duplicated region. After filtering out such sites, we ended up with 3,818 sites spanning 2,365 genes. Additional filtering based on linkage was applied to avoid potential back mutations among shared SNPs. Here, we selected genes with shared haplotypes such that a pair of shared SNPs were in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.3) in A. thaliana and in at least two out of the three other common species. Moreover, we required that at least one of the shared SNPs was nonsynonymous.

We used GOWINDA71 to test enrichment for Gene Ontology categories (GO slim) for identified genes under balancing selection. Total (private and shared) coding SNPs identified for the four common species (A. thaliana, A. halleri, A. lyrata and A. arenosa) were used as a background set, and shared coding SNPs segregating in all four species (3,818 SNPs in 2,365 genes) and that passed additional LD filtering (340 SNPs in 129 genes) were used as the query sets. We ran GOWINDA with 100,000 simulations in 'gene' mode, assuming that only SNPs located inside a gene are associated with the corresponding gene (—gene–definition 'gene'). Additionally to GO_SLIM terms from TAIR10 we created and tested GO term for NB-LRR gene family previously identified72.

Clade-specific divergence in common Arabidopsis species.

To check for clade-specific divergence we tested for enrichment of particular A. thaliana GO_SLIM and INTERPRO categories in the diverged genes for the major clades A. halleri, A. lyrata, and A. arenosa, as well as for A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana as one clade. Fst, nucleotide diversity and Tajima's D for each gene (including UTR regions) in each clade were calculated using msABC73 'observed' mode (–obs). Several cut-off combinations were tried, and for some comparisons we also considered nucleotide diversity as this resulted in more interesting results. The reported P values do not take this implicit multiple testing into account and should thus be interpreted with caution. There is no obvious way of correcting for this kind of overfitting, and there is also no way of knowing a priori what parameters might be appropriate to detect selection in a given species.

For A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana, divergent genes were identified as those with Fst values in the upper eighty-fifth percentile in comparisons between this clade and A. halleri, A. lyrata and A. arenosa. For A. halleri, we used the upper eightieth percentile threshold for Fst and the additional criterion of nucleotide diversity in the lower fiftieth percentile in A. halleri. For A. lyrata and A. arenosa, divergent genes were identified as having Fst values in the upper eighty-fifth percentile, and we also required nucleotide diversity in the lower forty-fifth percentile and Tajima's D values in the lower thirty-fifty percentile. Individuals that showed signs of introgression between A. lyrata and A. arenosa in the ADMIXTURE analysis we excluded.

We used only general A. thaliana GO_SLIM categories (TAIR10), which were not deeper than the third node on a GO categories graph for 'biological process' root category (136 categories in total) and also used only the first node categories of INTERPRO database (627 categories). We also required a minimum of five genes from a category to be present in a candidate set to perform a test. Gene categories enrichment was tested by Fisher's exact test: all P values were adjusted for multiple testing (using R function 'p.adjust' with method = 'fdr').

Accession codes are listed in Supplementary Data Set 1.

References

Hohmann, N. et al. Taming the wild: resolving the gene pools of non-model Arabidopsis lineages. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 224 (2014).

Cao, J. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple Arabidopsis thaliana populations. Nat. Genet. 43, 956–963 (2011).

Long, Q. et al. Massive genomic variation and strong selection in Arabidopsis thaliana lines from Sweden. Nat. Genet. 45, 884–890 (2013).

Schmitz, R.J. et al. Patterns of population epigenomic diversity. Nature 495, 193–198 (2013).

Hylander, N. Cardaminopsis suecica (Fr.) Hiit., a northern amphidiploid species. Bull. Jard. Bot. État Bruxelles. 27, 591–604 (1957).

Shimizu, K.K., Fujii, S., Marhold, K., Watanabe, K. & Kudoh, H. Arabidopsis kamchatica (Fisch. ex DC.) K. Shimizu & Kudoh and A. kamchatica subsp. kawasakiana (Makino) K. Shimizu & Kudoh, new combinations. Acta phytotaxonomica et geobotanica 56, 163–172 (2005).

Shimizu-Inatsugi, R. et al. The allopolyploid Arabidopsis kamchatica originated from multiple individuals of Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis halleri. Mol. Ecol. 18, 4024–4048 (2009).

Schmickl, R. & Koch, M.A. Arabidopsis hybrid speciation processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14192–14197 (2011).

Hohmann, N., Wolf, E.M., Lysak, M.A. & Koch, M.A. A time-calibrated road map of Brassicaceae species radiation and evolutionary history. Plant Cell 27, 2770–2784 (2015).

Shimizu, K.K. Ecology meets molecular genetics in Arabidopsis. Popul. Ecol. 44, 221–233 (2002).

Willems, G. et al. The genetic basis of zinc tolerance in the metallophyte Arabidopsis halleri ssp. halleri (Brassicaceae): an analysis of quantitative trait loci. Genetics 176, 659–674 (2007).

Browning, B.L. & Browning, S.R. Improving the accuracy and efficiency of identity-by-descent detection in population data. Genetics 194, 459–471 (2013).

Nordborg, M. Linkage disequilibrium, gene trees and selfing: an ancestral recombination graph with partial self-fertilization. Genetics 154, 923–929 (2000).

Durand, E.Y., Patterson, N., Reich, D. & Slatkin, M. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2239–2252 (2011).

Green, R.E. et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328, 710–722 (2010).

Nordborg, M. et al. The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol. 3, e196 (2005).

Hu, T.T. et al. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nat. Genet. 43, 476–481 (2011).

Bechsgaard, J.S., Castric, V., Charlesworth, D., Vekemans, X. & Schierup, M.H. The transition to self-compatibility in Arabidopsis thaliana and evolution within S-haplotypes over 10 Myr. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1741–1750 (2006).

Shimizu, K.K. & Tsuchimatsu, T. Evolution of selfing: recurrent patterns in molecular adaptation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 593–622 (2015).

Slatkin, M. & Pollack, J.L. Subdivision in an ancestral species creates asymmetry in gene trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 2241–2246 (2008).

Nagylaki, T. Fixation indices in subdivided populations. Genetics 148, 1325–1332 (1998).

Ioerger, T.R., Clark, A.G. & Kao, T.H. Polymorphism at the self-incompatibility locus in Solanaceae predates speciation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9732–9735 (1990).

Klein, J., Satta, Y., Takahata, N. & O'hUigin, C. Trans-specific Mhc polymorphism and the origin of species in primates. J. Med. Primatol. 22, 57–64 (1993).

Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989).

Leffler, E.M. et al. Multiple instances of ancient balancing selection shared between humans and chimpanzees. Science 339, 1578–1582 (2013).

Cui, X., Fan, B., Scholz, J. & Chen, Z. Roles of Arabidopsis cyclin-dependent kinase C complexes in cauliflower mosaic virus infection, plant growth, and development. Plant Cell 19, 1388–1402 (2007).

Shen, W., Reyes, M.I. & Hanley-Bowdoin, L. Arabidopsis protein kinases GRIK1 and GRIK2 specifically activate SnRK1 by phosphorylating its activation loop. Plant Physiol. 150, 996–1005 (2009).

Carvalho, C.M. et al. A novel nucleocytoplasmic traffic GTPase identified as a functional target of the bipartite geminivirus nuclear shuttle protein. Plant J. 55, 869–880 (2008).

Brutus, A., Sicilia, F., Macone, A., Cervone, F. & De Lorenzo, G. A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9452–9457 (2010).

Krämer, U. Metal hyperaccumulation in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 517–534 (2010).

Verbruggen, N., Hermans, C. & Schat, H. Molecular mechanisms of metal hyperaccumulation in plants. New Phytol. 181, 759–776 (2009).

Toivainen, T., Pyhäjärvi, T., Niittyvuopio, A. & Savolainen, O. A recent local sweep at the PHYA locus in the Northern European Spiterstulen population of Arabidopsis lyrata. Mol. Ecol. 23, 1040–1052 (2014).

Rosenberg, N.A. & Nordborg, M. Genealogical trees, coalescent theory and the analysis of genetic polymorphisms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 380–390 (2002).

Nishihara, H., Maruyama, S. & Okada, N. Retroposon analysis and recent geological data suggest near-simultaneous divergence of the three superorders of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5235–5240 (2009).

Hallström, B.M. & Janke, A. Mammalian evolution may not be strictly bifurcating. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 2804–2816 (2010).

Garrigan, D. et al. Genome sequencing reveals complex speciation in the Drosophila simulans clade. Genome Res. 22, 1499–1511 (2012).

Brandvain, Y., Slotte, T., Hazzouri, K.M., Wright, S.I. & Coop, G. Genomic identification of founding haplotypes reveals the history of the selfing species Capsella rubella. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003754 (2013).

Martin, S.H. et al. Genome-wide evidence for speciation with gene flow in Heliconius butterflies. Genome Res. 23, 1817–1828 (2013).

Jónsson, H. et al. Speciation with gene flow in equids despite extensive chromosomal plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18655–18660 (2014).

Mailund, T., Munch, K. & Schierup, M.H. Inferring the process of human–chimpanzee speciation. eLS. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0020833.pub2 (2014).

Fontaine, M.C. et al. Mosquito genomics. Extensive introgression in a malaria vector species complex revealed by phylogenomics. Science 347, 1258524 (2015).

Lamichhaney, S. et al. Evolution of Darwin's finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing. Nature 518, 371–375 (2015).

Suh, A., Smeds, L. & Ellegren, H. The dynamics of incomplete lineage sorting across the ancient adaptive radiation of neoavian birds. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002224 (2015).

Pease, J.B., Haak, D.C., Hahn, M.W. & Moyle, L.C. Phylogenomics reveals three sources of adaptive variation during a rapid radiation. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002379 (2016).

Ellstrand, N.C. Is gene flow the most important evolutionary force in plants? Am. J. Bot. 101, 737–753 (2014).

Mallet, J., Besansky, N. & Hahn, M.W. How reticulated are species? BioEssays 38, 140–149 (2016).

Alexander, D.H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Reich, D. et al. Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 516–528 (2011).

Doyle, J.J. & Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

DePristo, M.A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6, 80–92 (2012).

The 1001 Genomes Consortium. 1,135 genomes reveal the global pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.063 (2016).

Akama, S., Shimizu-Inatsugi, R., Shimizu, K.K. & Sese, J. Genome-wide quantification of homeolog expression ratio revealed nonstochastic gene regulation in synthetic allopolyploid Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e46 (2014).

Paradis, E., Claude, J. & Strimmer, K. APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290 (2004).

Sukumaran, J. & Holder, M.T. DendroPy: a Python library for phylogenetic computing. Bioinformatics 26, 1569–1571 (2010).

Pool, J.E., Hellmann, I., Jensen, J.D. & Nielsen, R. Population genetic inference from genomic sequence variation. Genome Res. 20, 291–300 (2010).

Korneliussen, T.S., Albrechtsen, A. & Nielsen, R. ANGSD: Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 356 (2014).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Castresana, J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 540–552 (2000).

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Ho, S.Y. & Guindon, S. Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1695–1701 (2012).

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Kainer, D., Mayer, C. & Stamatakis, A. Selecting optimal partitioning schemes for phylogenomic datasets. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 82 (2014).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Drummond, A.J., Suchard, M.A., Xie, D. & Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973 (2012).

Stadler, T. On incomplete sampling under birth-death models and connections to the sampling-based coalescent. J. Theor. Biol. 261, 58–66 (2009).

Drummond, A.J., Ho, S.Y., Phillips, M.J. & Rambaut, A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 4, e88 (2006).

Wiuf, C., Zhao, K., Innan, H. & Nordborg, M. The probability and chromosomal extent of trans-specific polymorphism. Genetics 168, 2363–2372 (2004).

Gutenkunst, R.N., Hernandez, R.D., Williamson, S.H. & Bustamante, C.D. Inferring the joint demographic history of multiple populations from multidimensional SNP frequency data. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000695 (2009).

Kofler, R. & Schlötterer, C. Gowinda: unbiased analysis of gene set enrichment for genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 28, 2084–2085 (2012).

Guo, Y.L. et al. Genome-wide comparison of nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 757–769 (2011).

Pavlidis, P., Laurent, S. & Stephan, W. msABC: a modification of Hudson's ms to facilitate multi-locus ABC analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 723–727 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Belkhadir, K. Bomblies and J. de Meaux for discussions and comments on the manuscript; R. Schmickl, L. Paule, C. Tremblay, J. Cayouette, G. Mitrow, H. Tsukaya and O. Savolainen for help with collections; and P. Forai, M. Hatakeyama and M. Kiefer for IT support. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG SPP 1529 to M.A.K., U.K., M.N., C.S., D.W. and A.W., and KO 2302/13-2, KO 2302/14-1 to M.A.K.), by the Swiss National Science Foundation and URPP Evolution in Action (to K.K.S.), by HFSP (to J.S. and K.K.S.), by the EU Plant Fellows Program (to T.P.), by the Czech Science Foundation (P506/12/0668 to K.M.), and by the Austrian Science Funds (FWF DK W1225 to C.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.K., U.K., M.N., K.S. and D.W. conceived of and planned the study. P.Y.N. and N.H. analyzed the data with help from M.N., C.S. and T.T. M.N. and P.Y.N. wrote the paper. V.N., J.A., G.M., A.G., T.P., O.M.F., S.H., T.S., A.W., J.S., K.M. and K.K.S. contributed plant material or contributed or generated sequence data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 2 Cross-validation errors of ancestral populations assignment for different number of clusters by ADMIXTURE.

Two local minima (K=5 and K=8) were chosen for further analysis shown on Figure 1.

Supplementary Figure 3 The structure of the genus Arabidopsis without polyploid individuals.

(a) Neighbor-joining tree based on a genetic distances, with C. rubella as outgroup. Nodes are labeled with percentage of individual gene trees supporting the split. (b) Overlapped neighbor-joining trees for 300 randomly chosen genes, based on genetic distances for each gene.

Supplementary Figure 4 Phylogenetic trees based on whole chloroplast genome sequence data including the outgroup taxa Camelina sativa, Capsella rubella and Capsella bursa-pastoris.

(a) BEAST analysis. Divergence times are indicated with 95% confidence intervals. (b) Maximum likelihood tree. Bootstrap support from 1000 replicates: ** 99-100%, * 95-98%.

Supplementary Figure 5 Distribution of shared identical-by-descent (IBD) blocks length in A. thaliana relatives identified with BEAGLE.

(a) Distribution of IBD blocks length identified within common species: A. arenosa, A. halleri and A. lyrata. (b) Distribution of IBD blocks length identified within local endemic Arabidopsis species: A. cebennensis, A. pedemontana and A. croatica. (c) Distribution of all identified IBD blocks between different Arabidopsis clades.

Supplementary Figure 7 Ancient gene flow between A. halleri and ancestral population of A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana.

(a) D statistics from ABBA-BABA tests shows that both A. cebennensis and A. pedemontana are closer to A. halleri than to either A. lyrata or A. arenosa. (b) Geographical distribution of A. cebennensis, A. pedemontana and European A. halleri lineages. Pink dashed line connects individuals sharing IBD blocks identified with BEAGLE.

Supplementary Figure 8 Tajima’s D estimator is higher for genes with shared polymorphism compared to all aligned genes.

Tajima’s D value in common Arabidopsis species for all analysed genes (white), genes with at least one shared SNP in all 4 species (green), genes with at least 2 linked shared SNP in all 4 species (orange); * indicates p-values <<0.01 (‘Mann-Whitney’ test).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–8 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 (PDF 1492 kb)

Supplementary Data Set 1

List of analysed samples with accession codes. (XLSX 16 kb)

Supplementary Data Set 2

List of genes, containing at least 2 linked SNPs segregating in all 4 common Arabidopsis species (A. thaliana, A. halleri, A. lyrata and A. arenosa). (XLSX 40 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons licence, users will need to obtain permission from the licence holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Novikova, P., Hohmann, N., Nizhynska, V. et al. Sequencing of the genus Arabidopsis identifies a complex history of nonbifurcating speciation and abundant trans-specific polymorphism. Nat Genet 48, 1077–1082 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3617

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3617

This article is cited by

-

Ancestral self-compatibility facilitates the establishment of allopolyploids in Brassicaceae

Plant Reproduction (2023)

-

Geographic Variation in Genomic Signals of Admixture Between Two Closely Related European Sepsid Fly Species

Evolutionary Biology (2023)

-

Recent speciation associated with range expansion and a shift to self-fertilization in North American Arabidopsis

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Parallel reduction in flowering time from de novo mutations enable evolutionary rescue in colonizing lineages

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Parallel adaptation in autopolyploid Arabidopsis arenosa is dominated by repeated recruitment of shared alleles

Nature Communications (2021)