Abstract

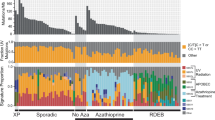

Here we report the discovery of recurrent mutations concentrated at an ultraviolet signature hotspot in KNSTRN, which encodes a kinetochore protein, in 19% of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Cancer-associated KNSTRN mutations, most notably those encoding p.Ser24Phe, disrupt chromatid cohesion in normal cells, occur in SCC precursors, correlate with increased aneuploidy in primary tumors and enhance tumorigenesis in vivo. These findings suggest a role for KNSTRN mutagenesis in SCC development.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Accession codes

References

Lomas, A., Leonardi-Bee, J. & Bath-Hextall, F. Br. J. Dermatol. 166, 1069–1080 (2012).

Durinck, S. et al. Cancer Discov. 1, 137–143 (2011).

Fang, L., Seki, A. & Fang, G. Cell Cycle 8, 2819–2827 (2009).

Vogelstein, B. et al. Science 339, 1546–1558 (2013).

Dunsch, A.K., Linnane, E., Barr, F.A. & Gruneberg, U. J. Cell Biol. 192, 959–968 (2011).

Davoli, T. et al. Cell 155, 948–962 (2013).

Zack, T.I. et al. Nat. Genet. 45, 1134–1140 (2013).

Biesterfeld, S., Pennings, K., Grussendorf-Conen, E.I. & Böcking, A. Br. J. Dermatol. 133, 557–560 (1995).

Ziegler, A. et al. Nature 372, 773–776 (1994).

Ziegler, A. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 4216–4220 (1993).

Kretz, M. et al. Genes Dev. 26, 338–343 (2012).

Liu, X., Jian, X. & Boerwinkle, E. Hum. Mutat. 34, E2393–E2402 (2013).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Koboldt, D.C. et al. Bioinformatics 25, 2283–2285 (2009).

Deng, X. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 267 (2011).

DePristo, M.A. et al. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

Ng, S.B. et al. Nature 461, 272–276 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank J.G. Rheinwald (Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center) for his generous gift of SCC cell lines. We thank A.E. Oro, H.Y. Chang, M. Diehn, M.P. Scott, S.E. Artandi, G.R. Crabtree and T. Waldman as well as A. Zehnder, X. Bao, B.K. Sun, R.J. Flockhart and V. Lopez-Pajares for presubmission review and helpful comments. This work was supported by the US Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and by US National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIH/NIAMS) grant AR43799 to P.A.K. C.S.L. is the recipient of career award K08 AR064732 from the NIH/NIAMS. A.S. is supported by NIH/National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS) grant GM074728 and American Cancer Society grant 120161-RSG. W.L.J. is the recipient of National Science Foundation (NSF) graduate research fellowship grant DGE-114747.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.L. designed and executed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. A.M., A.B., C.J.A., C.B.N., W.L.J., E.J.R., A.U. and Z.S. helped execute experiments, analyzed data and contributed to the design of experimentation. A.S. helped design experiments and analyzed data. J.K. and S.Z.A. performed tumor tissue acquisition and analysis. P.A.K. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 2 Expression of kinastrin in human skin and SCCs.

(a) Kinastrin is expressed in a broad variety of tissues. Kinastrin expression was extracted from the NextBio Body Atlas application (PLoS One 5, e13066, 2010). The dotted line indicates median expression. (b) Kinastrin expression in progenitor human primary keratinocytes11. The average FPKM of all expressed genes (FPKM > 1.5) in this population is shown for reference. (c) Kinastrin is expressed in normal skin and SCCs. Kinastrin expression was assayed in 76 cases of cutaneous SCC and 5 normal skin samples; representative images are shown. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Supplementary Figure 3 Somatic KNSTRN p.Ser24Phe mutations in SCC.

KNSTRN p.Ser24Phe mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Sequence chromatograms from a representative SCC and normal skin (NL) sample from the same individual are shown.

Supplementary Figure 4 KNSTRN mutations in SCC compared to other cancer types.

(a) KNSTRN mutation frequency by cancer type (Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404, 2012). (b) Distribution of mutations in the kinastrin coding sequence (Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404, 2012). The labeled mutations disrupt sister chromatid cohesion in normal cells. SXLP, SXLP motif; CC, coiled-coil region.

Supplementary Figure 5 Enforced expression of kinastrin p.Ser24Phe is stable in normal cells.

Western blot analysis of early-passage primary human keratinocytes following transduction with the three kinastrin isoforms. Endogenous kinastrin expression is shown in lane 1; only isoform 3 is present. Lanes 6 and 7 show the enforced protein expression used to assess sister chromatid cohesion and DNA content. Numbers indicate molecular mass in kilodaltons.

Supplementary Figure 6 Kinastrin p.Ser24Phe disrupts chromatid cohesion in SCC-13 cells.

(a) Western blot analysis of SCC-13 cells following transduction with N-terminally tagged (Flag-HA-(poly)His) kinastrin p.Ser24Phe versus wild-type kinastrin. The lower- and higher-molecular-weight bands represent endogenous and enforced kinastrin expression, respectively. (b) Quantification of unpaired chromatids. *P = 0.013, **P = 0.008; ns, not significant.

Supplementary Figure 7 Cancer-associated KNSTRN mutations disrupt chromatid cohesion in normal cells.

(a) Western blot analysis of early-passage primary human keratinocytes following transduction with KNSTRN p.Arg11Lys, p.Pro26Ser, p.Pro28Ser and p.Ala40Glu versus wild-type kinastrin. (b) Quantification of unpaired chromatids. *P = 0.05, **P < 0.03.

Supplementary Figure 8 Kinastrin p.Ser28Phe enhances aneuploidy in normal cells.

Early-passage, pooled primary human foreskin keratinocytes were transduced with dominant-negative p53 and LacZ (CTR), wild-type kinastrin (WT) or kinastrin p.Ser28Phe (S24F). Cells were grown in paclitaxel for 68 h to induce aneuploidy. (a) Percentage of primary human keratinocytes with DNA content >4N. Data shown represents the mean ± s.d. for biological duplicates with technical triplicates. *P = 0.0014, **P = 0.0004; ns, not significant. (b) Representative plots of cell cycle analysis are shown.

Supplementary Figure 9 Kinastrin p.Ser28Phe does not affect cell growth or cell cycle kinetics.

Early-passage primary human keratinocytes were transduced with LacZ (CTR), wild-type kinastrin (WT) or kinastrin p.Ser28Phe (S24F). (a) Equal numbers of cells were seeded in duplicate, and cell growth assays were performed in technical triplicates at each of the time points shown. (b) Asynchronously proliferating cells were stained with propidium iodide and assayed by flow cytometry in technical duplicates.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–9 (PDF 2225 kb)

Supplementary Tables 1–7

Supplementary Tables 1–7 (XLS 2080 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, C., Bhaduri, A., Mah, A. et al. Recurrent point mutations in the kinetochore gene KNSTRN in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 46, 1060–1062 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3091

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3091

This article is cited by

-

KNSTRN Is a Prognostic Biomarker That Is Correlated with Immune Infiltration in Breast Cancer and Promotes Cell Cycle and Proliferation

Biochemical Genetics (2024)

-

Advances in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Nature Reviews Cancer (2023)

-

Emerging precision diagnostics in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

npj Precision Oncology (2022)

-

Analysis of mutations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma reveals novel genes and mutations associated with patient-specific characteristics and metastasis: a systematic review

Archives of Dermatological Research (2022)

-

Positive association between actinic keratosis and internal malignancies: a nationwide population-based cohort study

Scientific Reports (2021)