Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton could bring very different approaches to addressing climate change if elected president.C. SENTER/AP; C. DHARAPAK/AP

Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton could bring very different approaches to addressing climate change if elected president.C. SENTER/AP; C. DHARAPAK/APIt is 20 January 2009, and the new US president has just been sworn into the Oval Office. Environmentalists are optimistic. Scientists, activists and politicians around the globe have their fingers crossed. For the first time in eight years, the United States is led by a politician who advocates quick and forceful action on global warming.

The question on everybody's mind is what comes next. It doesn't take much to prepare a policy paper and offer campaign sound bites about the dangers of global warming. It's also easy to grandstand one's green credentials once in office — perhaps by requiring Cabinet members to offset their carbon footprints or by departing the inauguration in a hybrid vehicle (although the armour-plating might well hamper its gas mileage). But it is a lot harder to bind the world's leading economy to a meaningful regulatory regime for greenhouse-gas emissions.

“We are talking about the largest environmental policy we have ever implemented.”

Joe Aldy

“We are talking about the largest environmental policy we have ever implemented, in terms of economic costs and economic benefits,” says Joe Aldy, a fellow at Resources for the Future, a non-partisan think-tank in Washington DC. “When you talk about policies of that stature, you have to have executive leadership.”

So what can the new president actually accomplish in those first days? The most immediate changes could be seen in the federal budget — in which billions of dollars are in play in research money for energy and global warming — or in new regulations controlling energy efficiency or carbon-dioxide emissions. Over the course of a presidency, though, the measure of true action would come in shepherding climate legislation through the halls of Congress, while leading the world in developing a successor to the Kyoto Protocol to control greenhouse gases.

On the domestic front, the Supreme Court set the stage for at least some new regulations in April, when it ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority to regulate carbon dioxide from vehicles (see Nature 446, 589; 2007). Regulating the gas would represent an old-school approach to environmental issues that forces every business to meet the same standards. This system has fallen out of favour with the advent of cap-and-trade systems in which businesses barter among themselves for the cheapest way to meet an overall mandate, but a president could use the threat of regulation to force action on meaningful cap-and-trade legislation in Congress. “It's really important to recognize,” says Aldy, “that the alternative to a new climate bill coming out of Congress is not no carbon regulation, which is the status quo, but very costly carbon regulation.”

A new president could even interpret the Supreme Court ruling to include carbon-dioxide emissions from power plants. “If you had decent regulatory standards for vehicles, fuels and power plants, you will have dealt with 60% of US emissions,” says David Doniger, climate-policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group based in New York.

Capitol support

The next administration is likely to face a Congress in which both houses support some sort of action on global warming. Several major emissions-reduction bills have already been introduced (see pages 333 and 342), but most experts expect the debate to extend well into the next administration. And while congressional leaders set the legislative agenda, the president can set the tone on whether the executive branch will back up any particular action. The White House can, for instance, tap a team of experts to meet with industry and activist groups, shuffle proposals to and from Capitol Hill, and otherwise ensure that the issue receives the sustained attention necessary to iron out an agreement.

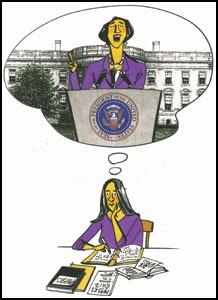

See also our Climate politics special, and take the quiz: What every president should knowM-H Jeeves

See also our Climate politics special, and take the quiz: What every president should knowM-H JeevesWhen a president is willing, practical politics can sometimes follow swiftly. On coming into office in 1989, for example, President George H. W. Bush made action on acid rain a priority. Top presidential advisers on domestic policy, the environment and economics began working on the issue, says Jeff Holmstead, who joined the team in 1989 and went on to head the air and radiation division at the EPA under the current administration. “For them it was essentially a full-time job,” he says. “These were the senior-most people in the White House who would meet about this every day.” As a result, legislation that had floundered in Congress for nearly a decade took off, and amendments to the Clean Air Act passed the following year, establishing a cap-and-trade programme for sulphur dioxide that would later serve as a model for the Kyoto Protocol.

A president could also take advantage of manpower and expertise that Congress lacks. In this case, that means marshalling career experts at agencies such as the EPA and the Department of Energy to tackle global warming. Currently in climate legislation, says Doniger, “you have literally a handful of staff on the Hill trying to put the whole thing together, and there are a lot of experts in the agencies who are being held back. If you are trying to build a skyscraper and you are trying to learn welding at the same time, it's more difficult than if you have all the welders there with you”.

Bureaucratic challenges

Charismatic candidates, but how green are their policies? From left to right: Fred Thompson, Barack Obama, John McCain and John Edwards.J. L. MAGANA/AP; S. SENNE/AP; J. RAOUX/AP; C. NEIBERGALL/AP

Charismatic candidates, but how green are their policies? From left to right: Fred Thompson, Barack Obama, John McCain and John Edwards.J. L. MAGANA/AP; S. SENNE/AP; J. RAOUX/AP; C. NEIBERGALL/APAnother immediate move that a new president could make would be to restructure the government's $1.7-billion Climate Change Science Program, which coordinates climate research among 13 agencies. A recent National Academies report criticized the red tape ensnaring the programme, which reports to multiple organizations within the White House. “This is such a huge challenge that you can't have it mired in bureaucracy,” says Eileen Claussen, president of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change in Arlington, Virginia. “You have to have direct links into the decision makers, and that means the cabinet level and the White House.”

The administration could also make it easier for individual states to pursue their own programmes. The administration of George W. Bush has so far refused to rule on a petition from California that seeks permission to regulate carbon-dioxide emissions from automobiles. Even if Bush decides to deny that petition in favour of the federal regulations he is expected to issue next year, a new president might be able to revisit that.

Getting the domestic agenda in order is just the first major step for a new president. The next would be coordinating that with a major international change in agenda, which is something only a president can do. “You've got to work on parallel tracks,” says Dan Esty, director of the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy in New Haven, Connecticut. “You don't bring a bill to Congress until you've got an international treaty tied down, but you don't go to the international community without a series of domestic packages.”

“All the president has to do is essentially get on the phone and begin talking.”

Robert Stavins

President Bush has alienated much of the world by refusing to endorse any mandatory greenhouse-gas reductions, but the new administration will be in a position to assume a leadership role as the international community works toward a post-Kyoto agreement. “All the president has to do is essentially get on the phone to the European Union, the G8 countries, the other major economies and developing nations, and begin talking,” says Robert Stavins, an economist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Some experts believe the new president might even be able to push a new approach onto the international agenda if fellow world leaders believe the United States is serious about global warming. Yvo de Boer, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, has already signalled a willingness to entertain alternative ideas to ensure that everybody is on board the next global climate treaty. He says the notion of using a variety of national commitments — things such as renewable-energy standards, fuel-efficiency regulations or even elimination of energy subsidies — might be worth considering in addition to Kyoto-style carbon caps. Different types of commitments would be available to countries facing various economic and political realities.

De Boer also downplays his expectations of progress under a new administration, pointing out that Kyoto itself serves as a reminder of the limitations of the US presidency and the power of lawmakers on Capitol Hill. “It was President Clinton who never took the Kyoto Protocol to the Senate, because he knew he wouldn't get it through,” he says. “The Kyoto experience shows that if an administration negotiates something that the Senate isn't willing to ratify, you are not really that much better off.”

Internal doubts

ADVERTISEMENT

As if leading the free world weren't enough, the new president will also have to address any lingering scepticism from the American public. Global warming consistently ranks as an issue of concern to US voters, but some polls put it far behind other national priorities such as terrorism, education, immigration and health care. A new leader might even be able to help activists establish a new, more hopeful icon for global warming. Polar bears on melting ice floes might not be enough to convince Americans, long accustomed to cheap energy, that $5-per-gallon gasoline is acceptable, fears Severin Borenstein, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley. “But maybe a charismatic leader can get people to make sacrifices over the long term,” he says.

In the end, many experts expect that whatever the next president achieves domestically will set the standard for a post-Kyoto agreement. Many international delegates hope to achieve an agreement on the post-Kyoto framework by 2009, an aggressive goal that leaves the new president less than a year to get everything done. “It's more realistic to look at early-to-mid 2010,” says Esty. “Three or four months for the administration to get its feet on the ground, a year to get the negotiations done. It's a fast pace, but a doable one.”

Jeff Tollefson covers climate, energy and the environment for Nature.