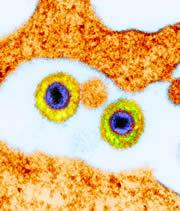

Lurking virus: could herpesviruses become a part of our normal immune system?DR KLAUS BOLLER / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Lurking virus: could herpesviruses become a part of our normal immune system?DR KLAUS BOLLER / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYThe herpesviruses bring untold suffering, but may not be all bad. Chronic latent infection with specific viral strains protects mice against some bacterial infections, a Nature study reveals this week1.

Almost all humans become infected with herpesviruses during childhood. After the acute initial infection ends, most of these viruses enter a dormant state and remain in the host for the rest of its life. In the vast majority of the population this will only result in a one-time, non-lethal infection such as chickenpox, herpes or mononucleosis. But in some people they can be devastating, leading to cancers such as lymphoma, blindness in AIDS patients, and congenital deafness in infants.

Unsurprisingly, the viruses are generally thought of as having no redeeming qualities. But Herbert Virgin and his colleagues at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri, have discovered that this is not necessarily true.

Unplagued mice

“The only good virus is a dead one.”

Bernard Roizman, University of Chicago

Virgin and his team were curious about the effect of latent herpesvirus infection on the function of the immune system. They infected some mice with one of two types of mouse herpesvirus and exposed them to bacterial pathogens that cause encephalitis, meningitis and plague. Mice that had been infected with herpesvirus showed significantly more resistance to these bacteria than mice that had not been infected.

Not all herpesviruses have this effect, the team adds. The type that causes herpes itself does not seem to have a protective effect. And they suspect, but don't yet know, that the type that causes chickenpox doesn't either.

The team wondered whether the latent version of some herpesviruses might have an effect on the immune system. To test this, they used a mutant strain of a mouse herpesvirus that could only initiate an acute infection and then faded away. Mice infected with this virus showed no resistance to bacterial pathogens.

"I think our data are going to change the way we look at herpesvirus infection, but more importantly they are going to change the way we view our own immune systems," says Virgin. If these infections are playing a part in preparing us for subsequent bacterial infection then their relationship shifts from pathogenic to symbiotic, somewhat similar to the relationship we have with our gut bacteria, he says.

Odd couple

This raises questions about how long a love-hate relationship has existed between herpesviruses and humans, and even about whether viral DNA should be considered a part of the infected person. "Perhaps we can consider these viruses, at least for some of us, as part of our 'normal' immune system," says Virgin.

ADVERTISEMENT

Herpesviruses descended from a strain that once infected a common ancestor of mammals, birds and reptiles. So animals and passenger herpesviruses have had more than 100 million years to co-evolve. It is possible that these viruses have had an important role in the evolution of human defences against disease.

But Virgin's results should not lead people to consider going and getting themselves infected. "I would not recommend that anyone be infected with a virus to enable them to develop an immune response to thwart infection," says Bernard Roizman, professor of virology at the University of Chicago, Illinois. "This research is very exciting, but in my mind the only good virus is a dead one or one that has been silenced for life."

Virgin agrees. "The degree to which our results apply to human disease and treatment remains to be determined," he says.

Visit our mighthave_benef.html">newsblog to read and post comments about this story.