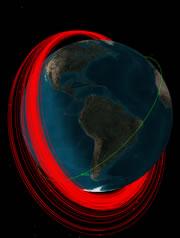

The military has mapped the debris field - just in case.courtesy of CSSI (

The military has mapped the debris field - just in case.courtesy of CSSI (Almost three weeks after the successful test of a Chinese anti-satellite weapon, the US military has catalogued more than 500 pieces of debris created by the destruction of the obsolete weather satellite (see 'Satellite kill creates space hazard'). Watchdog groups are keeping a keen eye on the space junk, and are using data from the military to learn more about the weapon's capabilities.

"For the next few years, whenever they have a spare weekend, you'll see another couple of dozen pieces of debris catalogued," says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. David Wright of the Union of Concerned Scientists, also in Cambridge, estimates that about 1,000 particles from the Chinese test are large enough to track.

The US military is capable of spotting pieces about 10 cm in size or larger, using a global system of optical telescopes, satellites and radar arrays. At present, the network tracks some 30,200 objects in orbit around the Earth, ranging from operational satellites to leftover rocket boosters and other debris.

Overnight, the test increased the overall amount of junk in orbit by about 1%, or several months' worth of normal accumulation.

Deadly debris

“Low earth orbit was already a dangerous place, and now it's measurably more dangerous.”

Jonathan McDowell

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

Although many of the pieces are small, their high speed means that they could still be destructive. The greatest threat may be to the space shuttle and the orbiting International Space Station.

Computer models show that some of that debris will cross the orbit of the space station, although the risk of a collision is small. NASA administrator Michael Griffin last week downplayed the threat: "At this point there is no requirement for a collision-avoidance manoeuvre," he told reporters.

But McDowell believes that as parts of the wreckage begin to fall back to Earth, they could still pose a problem. "For the next few months, there's going to be a falling rain of crap through the station and shuttle altitude range," McDowell says. "Low Earth orbit was already a dangerous place, and now it's measurably more dangerous."

Wright estimates that the crash probably created an additional 50,000 particles between 1 and 10 centimetres in size. These will never be detected by radar but could still knock out other satellites. "It is worrisome," he says. Millions of even smaller undetectable particles are also potentially damaging, he adds.

Jianhua Li, a spokesman for the Chinese embassy in Washington, declined to comment on any danger posed by the test. Instead he referred Nature to a 24 January statement by Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Jianchao, which said that the test "does not pose a threat to any country".

Chain reaction

By looking at the trajectories of the debris and extrapolating backwards, Geoffrey Forden, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, has been able to learn more about the 'kill vehicle' used by the Chinese to knock out their satellite. Given the speed of the particles coming from the impact, the mass of the interceptor was probably less than 400 kg, he says.

ADVERTISEMENT

That would be light enough to reach geostationary orbit on a slightly larger Chinese missile. Satellites there are far above the target of this month's test, and occupy a narrow band of space that allows them to orbit at the same rate as Earth's rotation. They are mainly used for global positioning and communications, functions that make them enormously valuable. "Anything that destroys a geostationary satellite would be a disaster for us," Forden says.

Further tests, even on satellites in a low Earth orbit, could lead to a slow chain reaction of satellite explosions that might eventually wipe out key Earth-observing capabilities, says Wright. "I don't think this is a road the international community wants to go down," he warns.

Visit our militarytrackschinesesat.html">newsblog to read and post comments about this story.

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics