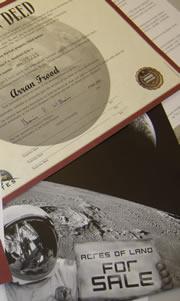

Deeds for sale on the internet may be little more than novelty gifts... but things may change.© Arran Frood / Nature

Deeds for sale on the internet may be little more than novelty gifts... but things may change.© Arran Frood / NatureWhy not buy some land on the Moon? There seems to be plenty available on the Internet, including plots going at a bargain £14.25 per acre (plus tax and fees) from the Lunar Embassy, the company selling the 'property' of American entrepreneur Dennis Hope, who infamously claimed practically all of the Solar System in 1980 because no one else had.

No one has officially recognized that Hope's lunar 'deeds' are anything more than novelty gifts. But more than 2 million have been sold since the 1980s, says the company, generating sales of millions of dollars out of empty space, leaving experts to wonder whether the commercial opportunities on the Moon might someday lead to real sales; and to suggest that perhaps they should.

A growing body of financiers, lawyers and space enthusiasts believe that the recognition of personal property rights 'out there' is the only realistic way to finance the new frontier of commercially driven space exploration.

Legal ownership of the Moon by countries is prevented by the 1967 UN Outer Space Treaty. This has been ratified or signed by more than 125 countries, including all the main space players (the United States, Russia, Japan, China and India). By its mandate, the American flags currently 'flying' on the Moon do not give the United States a greater claim to it over any other nation.

Read our Moon special to find out more.NASA

Read our Moon special to find out more.NASABut on the matter of private ownership, things are arguably more murky. The United Nations attempted to tackle this with the 1979 Moon Treaty, which states that no pieces of the Moon can become property of any "state, international or national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person". But, perhaps because the prospect of any risk in this area seemed so far away, hardly anyone signed: only 12 countries agreed, none of them major players in the space game.

Louis Freedman, co-founder of the California-based Planetary Society, whose mission is to inspire planetary exploration and to seek out new life, testified to a Senate hearing on whether the United States should sign up: "I told them that making laws in the absence of knowing what you are trying to make a law about is not a good idea," he says.

But the times are changing, with nations gearing up to return to the Moon ( see ' Fly me to the moon'), private companies offering tourist trips into space, and private interests being actively encouraged by bodies such as NASA to contribute to the next wave of space exploration.

The sky's the limit

According to the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs, says legal officer Sama Payman, there can be no private property rights, because countries would have to claim sovereignty to award their citizens titles of ownership. "This would be breaching laws on Earth," she says.

Others disagree. "The Outer Space Treaty is ambiguous as to the precise nature and scope of the property rights that an individual may hold in celestial bodies," says California-based space law expert Ezra Reinstein. Glenn Reynolds, who teaches space law at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, goes further. "Personal property rights are not banned by the Outer Space Treaty."

That provides wiggle room that many are keen to exploit. Alan Wasser is chairman of the Space Settlement Institute, a Texas-based organization that campaigns for individual and company property rights to be extended to celestial bodies such as the Moon. Capitalist economic principles, he says, are the only way the human race will be able to properly fund the establishment of permanent bases on the Moon and beyond.

"If national appropriation of lunar territory had not been banned," says Wasser, "there would be many people living on the Moon today."

Hopes and dreams

“If national appropriation of lunar territory had not been banned, there would be many people living on the Moon today”

Alan Wasser

Chairman of the Space Settlement Institute

That may be an overly optimistic statement, but the group is aiming to make it a reality. The Space Settlement Institute has drawn up 'land claims recognition' legislation and published draft acts with which to lobby the US government to recognize property rights on the Moon.

"What Dennis Hope does is a bad idea, as it's making it harder to promote a realistic and good idea," says Wasser. "On the plus side, it's a useful market test: it answers the question of whether people will want to own land on the Moon." The answer, they say, is clearly yes. "Once someone has built a spaceship that's running back and forth, people will pay when land ownership is possible," says Wasser.

"Right now it's more science fiction, utopia, just dreams," says Freedman. "Ninety-four spacecraft and 24 people have been there. There's no gold; there's nothing to go back for — it's just a stepping stone." But, he adds, if the Moon has commercial resources, such as minable amounts of helium-3, then "there would have to be a framework for international discussions".

If push came to shove, any country could just withdraw from the Outer Space Treaty, says Payman. It isn't simple, and such a move might cause worldwide furore and sour diplomatic relations. But it is possible; the United States pulled out of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, for example. "The world and countries can do a lot of stupid things," notes Freedman.

Use it, don't own it

More likely, analysts suggest, countries would simply exploit the Moon without claiming ownership of the land itself.

The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, for example, allows the United States to recover and exploit mineral resources of the high seas without asserting sovereign rights or ownership over them. This could serve as a precedent for utilization of material on the Moon, some say1. "All we need to do is to reinterpret the Outer Space Treaty, to allow the recognition of private ownership," says Wasser.

For the moment there are no indications that extra-terrestrial land claims will be upheld. But private industry is making inroads in space. NASA has just awarded its US$500 million Commercial Orbital Transportation Services contract to two private companies, SpaceX, based in California, and Rocketplane Kistler, based in Oklahoma, to service the International Space Station. Private land ownership could offer further incentives for commercial involvement.

ADVERTISEMENT

As Francis Williams of MoonEstates, the UK branch of the Lunar Embassy (and self-declared 'celestial ambassador to planet Earth') says of the Hope claims, "more than 2 million buyers take it seriously enough. That's eight times the population of Iceland."

"Our products make people happy, we're not exploiting anyone and if anyone complains we refund their money instantly," says Williams. "What's important though is that we have stimulated and opened up a wider debate."

A debate that may now be ripe for further discussion.

Visit our newsblog to read and post comments about this story.

Chairman of the Space Settlement Institute