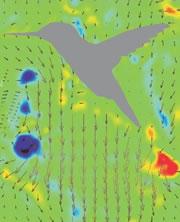

An analysis shows air vortices at the tip of a hummingbird’s wings as it flies.© Douglas R. Warrick, Bret W. Tobalske and Donald R. Powers

An analysis shows air vortices at the tip of a hummingbird’s wings as it flies.© Douglas R. Warrick, Bret W. Tobalske and Donald R. PowersDoes a hummingbird fly like an insect or a bird? A bit like both, according to aerodynamic research.

"What led us to this study was the long-held view that hummingbirds fly like big insects," says Douglas Warrick, of Oregon State University in Corvallis. Many experts had argued that hummingbirds' skill at hovering, of which insects are the undisputed masters, means that the two groups may stay aloft in the same way: by generating lift from a wing's upstroke as well as the down.

This turns out to be only partially true. Other birds get all of their lift from the downstroke, and insects manage to get equal lift from both up and down beats, but the hummingbird lies somewhere in between. It gets about 75% of its lift from the downstroke, and 25% from the upwards beat.

Sweet deal

“Their wings are a marvellous result of the considerable demands imposed by sustained hovering flight.”

Douglas Warrick

Oregon State University, Corvallis

Warrick and his team investigated the birds' performance by looking at the swirls of air left in their wake. To do this, they trained rufous hummingbirds (Selasphorus rufus) to hover in place while feeding from a syringe filled with sugar solution.

They filled the air with a mist of microscopic olive-oil droplets, and shone a sheet of laser light in various orientations through the air around the birds to catch two-dimensional images of air currents. A couple of quick photographs taken a quarter-second apart caught the oil droplets in the act of swirling around a wing.

Although hummingbirds do flap their wings up and down in relation to their body, they tend to hold their bodies upright so that their wings flap sideways in the air. To gain lift with each stroke the birds partially invert their wings, so that the aerofoil points in the right direction. Their flight looks a little like the arm and hand movements used by a swimmer when treading water, albeit it at a much faster pace.

ADVERTISEMENT

Insects attain the same lift with both strokes because their wings actually turn inside out. A hummingbird, with wings of bone and feathers, isn't quite so flexible. But the birds are still very efficient. "Their wings are a marvellous result of the considerable demands imposed by sustained hovering flight," Warrick says. "Provided with enough food, they can hover indefinitely."

The researchers add that the hummingbird's flapping bears a striking resemblance to that of large insects such as hawkmoths, an example of how evolution can produce similar engineering solutions in hugely distant animal groups.

Oregon State University, Corvallis