The US author Michael Crichton is well known for taking some strand of contemporary science, stretching it a little, and weaving it into the narrative of a thriller that goes on to become a best-seller and a blockbuster movie.

It worked for microbiology in The Andromeda Strain, it worked for genetic engineering in Jurassic Park, and it worked for nanotechnology and distributed intelligence in Prey.

In many ways, Crichton's latest novel, State of Fear (published by HarperCollins on 7 December), seems to use the same, highly lucrative principle of uniting science-based terrors with eye-catching imagery.

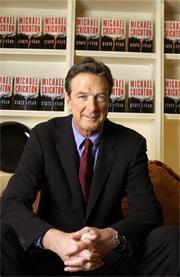

Michael Crichton’s new book questions whether global warming is really happening.© AP Photo/Jim Cooper

Michael Crichton’s new book questions whether global warming is really happening.© AP Photo/Jim CooperBut this time, Crichton's demons are not rogue nanobots or monstrous dinosaurs. This time, the agents of destruction and carnage are, as the publicity material puts it, "scientists and activists committed to the cause of environmental protection".

The plot centres on the efforts of an environmental activist group called the National Environmental Resource Fund to engineer a series of catastrophic events (with plenty of cinematic potential) that will lend spurious support to the 'theory' of global warming.

The story's hero, an MIT professor called Kenner, realizing that global warming isn't actually happening at all, uncovers the horrendous lengths to which the activists are willing to go to persuade society that the world really is in danger from climate change.

“Michael Crichton writes from a firm foundation of actual research challenging common assumptions about global warming.”

Publicity material

State of Fear

We are told: "Kenner and his allies will take on harsh elements, vicious savages, and a man-made tsunami to save the world from the evil of scientific myths and corruptions." Scientific myths? Global warming? Ah, but this is just a novel, right?

Wrong. " State of Fear ", the blurb continues, "raises critical questions about the facts we believe in on the strength of esteemed experts and the media. Although the story is fiction, Michael Crichton writes from a firm foundation of actual research challenging common assumptions about global warming."

This research is detailed in an appendix to the novel, replete with graphs and scholarly citations. The novel itself contains footnotes to draw out the factual basis of the claims it makes.

Novel approach

Crichton did something similar in Prey, although it became clear that his vision of nanotechnology was acquired from the outer reaches rather than the mainstream of current science. But with State of Fear, Crichton has done some research of his own.

“Crichton doesn't like the idea that someone else is better placed to make judgments than he is.”

He went and read the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and found that, contrary to his initial assumptions, the evidence for human-induced global warming is paper-thin.

You might be forgiven for wondering whether the IPCC report that Crichton read was the same one that says: "There is new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities. Detection and attribution studies consistently find evidence for an anthropogenic signal in the climate record of the last 35 to 50 years". But Crichton wasn't going to buy into the scientists' conclusions; he wanted to make up his own mind, so he looked at the actual data.

And just look what they said! Far from growing steadily warmer over the past century, global mean temperatures actually declined slightly between 1940 and 1970! And the overall warming was a piffling 0.3 °C!

Part of the problem is that because Crichton has written a novel and not a scientific treatise, he has been granted the luxury of airing these views on arts programmes, where there is no one to challenge him. "You are nothing if not scrupulous in your research," one BBC presenter (who grills politicians ruthlessly) averred admiringly.

No one pointed out that the global mean temperature rise since 1900 is in fact about 0.8 °C and that this is more than has been observed at any time in the past one thousand years.

And the temporary reversal of the trend during 1940-70 is fully accounted for by climate models, as the IPCC report shows very clearly. The cooling seems to be largely the result of sulphur pollution, which created atmospheric sulphate aerosols that temporarily masked the greenhouse-gas-induced warming by reflecting sunlight and altering cloud cover.

Book token

Crichton claims that he has no political motives in State of Fear, and no interest in writing propaganda to support the United States' refusal to sign the Kyoto agreement to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. Rather, he just wants to expose the facts.

Although his apolitical agenda sounds genuine, this claim is hard to square with the way Crichton has ignored or dismissed facts in the IPCC's summary document that are plain to even the casual, non-scientific reader. Something else is going on.

He admits that he has a 'contrarian' disposition. Certainly that would seem consistent with the volte-face that allowed him, in Prey, to lambast the scientific community for being too gung-ho while now damning it for being too cautious and alarmist.

“Some non-scientists consider themselves as free to disagree with the second law of thermodynamics as they are to dispute Derrida's literary theory or the artistic value of the Surrealists.”

Either way, Crichton distrusts scientists: he compares them to Renaissance painters, who had to dance to the tune of their patrons, painting whatever picture the paymasters wanted. (This is strange when you consider that, for most US academics, the ultimate paymaster is George W. Bush.)

But this is, at root, the distaste that many smart people have for the notion of an expert. Crichton doesn't like the idea that someone else is better placed to make judgments than he is. He seems convinced that global warming is largely an invention of careerist scientists abetted by a partisan press.

And he seems to find something smug and stifling, if not dishonest, about consensus: "the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus", he says. "If it's consensus, it isn't science." (Might we all be permitted to agree, one wonders, that the Earth orbits the Sun?)

Considered responses

Scientists are bound to cry foul at all of this, and no doubt Crichton anticipates and even relishes the prospect. But they should consider their words carefully. The "trust us" line no longer persuades anyone. It is surely commendable that Crichton went and looked at the scientific data for himself, even if an unconscious agenda seems to have prevented him from absorbing it. And there are plenty of genuine uncertainties about global warming, even if most researchers now agree on the general picture.

ADVERTISEMENT

What we must resist, however, is a culture (common in literary circles) that regards scientific facts as a matter of personal taste. Some non-scientists consider themselves as free to disagree with the second law of thermodynamics as they are to dispute Derrida's literary theory or the artistic value of the Surrealists.

But this is the arrogance of the crank who concludes that he has been able to prove Fermat's last theorem with high-school algebra, while all the world's mathematicians have somehow been too inept to see the answer. There are times when we must accept that someone else really does know more than we do.

State of Fear