A boy walks by a collapsed house in Ojiya, about 260 kilometres northwest of Tokyo, on 23 October.© AP Photo/Koji Sasahara

A boy walks by a collapsed house in Ojiya, about 260 kilometres northwest of Tokyo, on 23 October.© AP Photo/Koji SasaharaSeismologists are struggling to make sense of the magnitude 6.8 earthquake that hit the Sea of Japan coast on 23 October.

The damage caused, including 27 deaths so far, is much more serious than would normally be expected from an earthquake of that size - at least in Japan, where buildings are constructed to withstand such events.

A surprisingly strong series of aftershocks, rivalling the main quake in magnitude, has continued to shake the area. And all this is happening in a region where scientists didn't even know there was an active fault.

Bad luck

What is clear is that the people in this rural area of the Niigata region coast were victims of particularly bad luck. Seismologist Naoshi Hirata of Tokyo University's Earthquake Research Institute, who returned from the area yesterday, described roads ripped up and major areas without electricity. "There are no lifelines," he says.

A 6.8 magnitude earthquake would not normally do so much damage, but the soft sediment that underlies the region was further weakened by one of the worst typhoon seasons in decades. "It was very unlucky," says Hirata.

“Things that were about to break after the first quake did break with the aftershocks.”

Seismologist Naoshi Hirata

Tokyo University

To make matters worse, aftershocks ranging from magnitude 5.5 to 6.5 continued for an hour after the original quake. "Having such aftershocks one after the other is very rare," says Hirata. "Things that were about to break after the first quake did break with the aftershocks."

Seismic newcomer

Right now, scientists have only a rudimentary picture of the new fault zone - a rectangle roughly 15 kilometres deep and 30 kilometres across.

The strong aftershocks imply that the crust below may have snapped off and then redistributed stress among many different faults. "This could be a very complicated fault system," says Hirata.

Today, as Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited the disaster-struck areas, the Japanese government authorized a national programme to investigate the new fault system. Hirata, who has already ventured out to place seismometers at nine locations near the fault, will lead the project.

Seismic measurements of the aftershocks will provide details on the location and shape of the original fault, and Global Positioning System receivers will be set up to measure the deformation of the Earth's crust.

Derailment debate

The quake has also focused discussion on whether there were enough safeguards to protect the area's housing and transport infrastructure. More than anything else, the first-ever derailment of a Japanese bullet train has caused concern.

The high-speed bullet trains transport hundreds of thousands of people every day. Although nobody on the train was injured, the derailment has worried Japanese travellers, who had assumed that safety measures would prevent such an event.

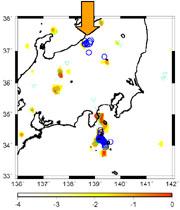

Saturday's quake (shown in blue along with the principal aftershocks, and indicated by the arrow) occurred very close to one of the hotspots (shown in yellow and red) predicted by John Rundle of the University of California-Davis.© John Rundle

Saturday's quake (shown in blue along with the principal aftershocks, and indicated by the arrow) occurred very close to one of the hotspots (shown in yellow and red) predicted by John Rundle of the University of California-Davis.© John RundleAn early-warning system shut off power to the train within a second of the quake registering, but that only slowed the train, which travelled on for a further two kilometres. However, the earthquake engineer who developed the system, Yutaka Nakamura of Tokyo-based System and Data Research, says this will still reduce damage to the train, by cutting the distance it travels over track that the earthquake has had time to tear up.

Such warning systems need to be paired with strong infrastructure, says Nakamura. And one of the problems with the latest disaster is that it came in an area that was not expected to suffer a major earthquake.

Hotspots highlighted

Earthquake specialist John Rundle at the University of California-Davis thinks he has an answer. He has devised a map of hotspots in Japan - a version of a map he has already produced for California - which he says highlights areas likely to have a major quake over the next five years.

Although his method still needs to prove itself, Rundle is chalking up this weekend's quake as a hit - it was centred just 15 kilometres east of one of his hotspots.

"The larger aftershocks have been moving more or less westward, towards the hotspot," he says.

Tokyo University