Abstract

Brain tumor initiating cells (BTICs), also known as cancer stem cells, hijack high-affinity glucose uptake active normally in neurons to maintain energy demands. Here we link metabolic dysregulation in human BTICs to a nexus between MYC and de novo purine synthesis, mediating glucose-sustained anabolic metabolism. Inhibiting purine synthesis abrogated BTIC growth, self-renewal and in vivo tumor formation by depleting intracellular pools of purine nucleotides, supporting purine synthesis as a potential therapeutic point of fragility. In contrast, differentiated glioma cells were unaffected by the targeting of purine biosynthetic enzymes, suggesting selective dependence of BTICs. MYC coordinated the control of purine synthetic enzymes, supporting its role in metabolic reprogramming. Elevated expression of purine synthetic enzymes correlated with poor prognosis in glioblastoma patients. Collectively, our results suggest that stem-like glioma cells reprogram their metabolism to self-renew and fuel the tumor hierarchy, revealing potential BTIC cancer dependencies amenable to targeted therapy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Accession codes

Primary accessions

Sequence Read Archive

Referenced accessions

Gene Expression Omnibus

References

Stupp, R. et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 10, 459–466 (2009).

Singh, S.K. et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 432, 396–401 (2004).

Gage, F.H. & Temple, S. Neural stem cells: generating and regenerating the brain. Neuron 80, 588–601 (2013).

Bao, S. et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 444, 756–760 (2006).

Liu, G. et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol. Cancer 5, 67 (2006).

Bao, S. et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 66, 7843–7848 (2006).

Cheng, L. et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell 153, 139–152 (2013).

Pavlova, N.N. & Thompson, C.B. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 23, 27–47 (2016).

Vander Heiden, M.G., Cantley, L.C. & Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033 (2009).

Ward, P.S. & Thompson, C.B. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell 21, 297–308 (2012).

Yan, H. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 765–773 (2009).

Turcan, S. et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature 483, 479–483 (2012).

Flavahan, W.A. et al. Brain tumor initiating cells adapt to restricted nutrition through preferential glucose uptake. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1373–1382 (2013).

Li, Z. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell 15, 501–513 (2009).

Hjelmeland, A.B. et al. Acidic stress promotes a glioma stem cell phenotype. Cell Death Differ. 18, 829–840 (2011).

Panopoulos, A.D. et al. The metabolome of induced pluripotent stem cells reveals metabolic changes occurring in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Res. 22, 168–177 (2012).

Masui, K. et al. Glucose-dependent acetylation of Rictor promotes targeted cancer therapy resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9406–9411 (2015).

Derr, R.L. et al. Association between hyperglycemia and survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1082–1086 (2009).

Brennan, C.W. et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155, 462–477 (2013).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455, 1061–1068 (2008).

Son, M.J., Woolard, K., Nam, D.H., Lee, J. & Fine, H.A. SSEA-1 is an enrichment marker for tumor-initiating cells in human glioblastoma. Cell Stem Cell 4, 440–452 (2009).

Liu, X. et al. Discrete mechanisms of mTOR and cell cycle regulation by AMPK agonists independent of AMPK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E435–E444 (2014).

Guo, D. et al. The AMPK agonist AICAR inhibits the growth of EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastomas by inhibiting lipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12932–12937 (2009).

Altman, B.J., Stine, Z.E. & Dang, C.V. From Krebs to clinic: glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 619–634 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. c-Myc is required for maintenance of glioma cancer stem cells. PLoS One 3, e3769 (2008).

Zheng, H. et al. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature 455, 1129–1133 (2008).

Stine, Z.E., Walton, Z.E., Altman, B.J., Hsieh, A.L. & Dang, C.V. MYC, metabolism, and cancer. Cancer Discov. 5, 1024–1039 (2015).

Suvà, M.L. et al. Reconstructing and reprogramming the tumor-propagating potential of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cell 157, 580–594 (2014).

Venere, M. et al. Therapeutic targeting of constitutive PARP activation compromises stem cell phenotype and survival of glioblastoma-initiating cells. Cell Death Differ. 21, 258–269 (2014).

Freije, W.A. et al. Gene expression profiling of gliomas strongly predicts survival. Cancer Res. 64, 6503–6510 (2004).

Madhavan, S. et al. Rembrandt: helping personalized medicine become a reality through integrative translational research. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 157–167 (2009).

Phillips, H.S. et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell 9, 157–173 (2006).

Lane, A.N. & Fan, T.W. Regulation of mammalian nucleotide metabolism and biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 2466–2485 (2015).

Wood, T. Physiological functions of the pentose phosphate pathway. Cell Biochem. Funct. 4, 241–247 (1986).

Boros, L.G. et al. Transforming growth factor β2 promotes glucose carbon incorporation into nucleic acid ribose through the nonoxidative pentose cycle in lung epithelial carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 60, 1183–1185 (2000).

Tong, X., Zhao, F. & Thompson, C.B. The molecular determinants of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in cancer cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 32–37 (2009).

Hosios, A.M. et al. Amino acids rather than glucose account for the majority of cell mass in proliferating mammalian cells. Dev. Cell 36, 540–549 (2016).

Ben-Sahra, I., Hoxhaj, G., Ricoult, S.J., Asara, J.M. & Manning, B.D. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science 351, 728–733 (2016).

Hensley, C.T. et al. Metabolic heterogeneity in human lung tumors. Cell 164, 681–694 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt cassette regulates purine nucleotide synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3521–3528 (2009).

Eyler, C.E. et al. Brain cancer stem cells display preferential sensitivity to Akt inhibition. Stem Cells 26, 3027–3036 (2008).

Vander Heiden, M.G. Targeting cancer metabolism: a therapeutic window opens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 671–684 (2011).

Brazelton, T.R. & Morris, R.E. Molecular mechanisms of action of new xenobiotic immunosuppressive drugs: tacrolimus (FK506), sirolimus (rapamycin), mycophenolate mofetil and leflunomide. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8, 710–720 (1996).

D'Cruz, D.P., Khamashta, M.A. & Hughes, G.R. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet 369, 587–596 (2007).

Sintchak, M.D. et al. Structure and mechanism of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase in complex with the immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid. Cell 85, 921–930 (1996).

Sidwell, R.W. et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of virazole: 1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide. Science 177, 705–706 (1972).

Wray, S.K., Gilbert, B.E., Noall, M.W. & Knight, V. Mode of action of ribavirin: effect of nucleotide pool alterations on influenza virus ribonucleoprotein synthesis. Antiviral Res. 5, 29–37 (1985).

Markland, W., McQuaid, T.J., Jain, J. & Kwong, A.D. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of the IMP dehydrogenase inhibitor VX-497: a comparison with ribavirin and demonstration of antiviral additivity with alpha interferon. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 859–866 (2000).

Bendell, J.C. et al. Phase I, dose-escalation study of BKM120, an oral pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 282–290 (2012).

Wen, P.Y., Lee, E.Q., Reardon, D.A., Ligon, K.L. & Alfred Yung, W.K. Current clinical development of PI3K pathway inhibitors in glioblastoma. Neuro-oncol. 14, 819–829 (2012).

Fang, X. et al. The zinc finger transcription factor ZFX is required for maintaining the tumorigenic potential of glioblastoma stem cells. Stem Cells 32, 2033–2047 (2014).

Xie, Q. et al. Mitochondrial control by DRP1 in brain tumor initiating cells. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 501–510 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate mass spectrometry analysis by R. Zhang, flow cytometry assistance by C. Shemo and S. O'Bryant, the glioblastoma tissue provided by M. McGraw and the Cleveland Clinic Tissue Procurement Service, and the IN528 model from I. Nakano at Ohio State University. We thank T. Roberts, J. Suh, G. Narla and members of the Rich laboratory for discussions. This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health grants CA197718, CA154130, CA169117, CA171652, NS087913 and NS089272 (J.N.R.), CA184090, NS091080 (S.B.) and CA168997, CA193256, CA201963 (J.W.L.); the James S. McDonnell Foundation (J.N.R.); the Research Programs Committees of the Cleveland Clinic (J.N.R. and K.Y.); Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland grant UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (J.N.R. and K.Y.); a P&F grant from NIH Resource Center for Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (RC-SIRM) at University of Kentucky (J.N.R. and K.Y.); and an ENGAGE grant from the National Center for Regenerative Medicine (K.Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W., K.Y. and J.N.R. designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. X.W., K.Y., Q.X., Q.W., S.C.M., C.G.H., T.E.M., W.Z., Z.H. and X.F. performed the experiments. K.Y., Y.S., L.J.Y.K., B.C.P., W.A.F., M.S., A.R., M.L.S. and T.H.H. performed database analyses. X.W., K.Y., Q.X., X.L. and J.W.L. performed metabolic experiments. S.B. provided scientific input and helped edit the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Genomic profiles and epigenetic characterizations comparing TCGA glioma specimens and T4121 BTICs.

(a) Mutations in coding sequences of frequently mutated genes in glioblastoma were identified through whole exome sequencing. Top left legend: Number of genes mutated in the selected gene set per specimen. Right legend: Percentage of specimens harboring a mutation in each gene. (b) Following quantile normalization across samples and median centering of gene expression, the top 10% most variant genes were used to cluster low grade and high grade glioma samples with RNA-seq data from T4121 BTICs. (c) Hierarchical clustering on the Pan-glioma probe set (1,300 probes) of DNA methylation 450K array data from BTICs (n = 3) and TCGA GBM (n = 155). (d) Hierarchical clustering on the IDH wild type probe set (914 probes) from DNA methylation 450K array data from IDH wild type samples among TCGA GBM specimens (n = 149) and BTICs (n = 3).

Supplementary Figure 2 BTICs contain elevated levels of purine degradation products compared to differentiated progeny.

Targeted mass spectrometry was performed to examine the level of a purine degradation product (hypoxanthine) using cell lysates of matched brain tumor initiating cells (BTICs) and differentiated glioma cells (DGCs) from five patient-derived glioblastoma specimens (T3691, T387, T4121, TIN528, and T3565). The relative levels of hypoxanthine were displayed normalized to DGCs. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 4 independent experiments per group. (T3691, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 26.710; T387, P = 0.0001, t(6) = 8.020; T4121, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 15.232; TIN528, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 48.811; T3565, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 13.688.) (b,c) Upregulation of purine synthesis pathway genes in CD15+ BTICs. Surgical specimens from two patients newly diagnosed with glioblastomas were immediately dissociated and prospectively sorted with beads conjugated with an anti-CD15 antibody in the absence of culture. The mRNA levels of six purine synthesis pathway enzymes (PRPS1, PPAT, ADSL, ADSS, GMPS, and IMPDH1) were measured using quantitative RT-PCR in matched CD15+ and CD15- populations derived from these two primary glioblastoma specimens. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (Patient 1: PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 34.461; PPAT, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 24.505; ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.579; ADSS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 50.404; GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.235; IMPDH1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 227.357. Patient 2: PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 34.882; PPAT, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 34.345; ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.519; ADSS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.213; GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 24.373; IMPDH1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 39.910.)

Supplementary Figure 3 Effects of purine synthesis inhibitors and AICAR.

(a-c) Sensitivity of four patient-derived DGC models (T387, T3565, T3691, and T4121) to three purine synthesis inhibitors: (a) mycophenolic acid, (b) mycophenolate mofetil, and (c) ribavirin. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. (d-f) Purine synthesis inhibitors attenuate GMP synthesis in BTICs. Two patient-derived BTIC models (T387 and T4121) were treated with each agent at concentrations that induce cellular responses: (d) mycophenolic acid (5 μM), (e) mycophenolate mofetil (5 μM), or (f) ribavirin (50 μM). DMSO was used as vehicle control. GMP levels were determined using targeted mass spectrometry. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 4 independent experiments per group. (Mycophenolic acid: T387, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 26.220; T4121, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 11.383. Mycophenolate mofetil: T387, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 13.002; T4121, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 21.557. Ribavirin: T387, P < 0.0001, t(6) = 33.811; T4121, p = 0.0002, t(6) = 7.257.) (g,h) Cell numbers of T387 and T4121 BTICs treated with 0, 100 μM, 200 μM, or 500 μM AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide). Time points were taken at days 1, 3, and 5. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (T387: day 3: 100 μM, P = 0.0031, t(4) = 4.755; 200 μM, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 7.731; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 9.579; day 5: 100 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.229; 200 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 30.923; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 31.516. T4121: day 3: 100 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.556; 200 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 26.207; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 27.817; day 5: 100 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 21.848; 200 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 23.165; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 65.922.) (i,j) Cell viability of T387 and T4121 BTICs treated with 0, 100 μM, 200 μM, or 500 μM AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide) was assessed by CellTiter-Glo. Time points were taken at days 1, 3, and 5. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (T387: day 3: 100 μM, P = 0.0022, t(10) = 4.089; 200 μM,, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 10.301; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 11.282; day 5: 100 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 7.399; 200 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 19.776; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 20.225. T4121: day 3: 100 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 7.434; 200 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 31.419; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 41.475; day 5: 100 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 7.521; 200 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 19.140; 500 μM, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 21.404.)

Supplementary Figure 4 Pathway analyses comparing BTICs to DGCs.

(a) Pathway map of enhancer associated gene network (identified with H3K27 acetylation ChIP-seq in T4121) comparing BTICs (red) versus DGCs (green). Pathways shown were identified using GREAT (http://bejerano.stanford.edu/great/public/html/), which was used to query the MSIGdb Broad pathway database (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/collections.jsp). Shown are networks with a FDR value of less than 0.05. (b-e) BTICs upregulate genes involved in the purine pathway. T4121 BTICs and DGCs underwent RNA-seq analysis in biologic duplicates with selective analysis of metabolic pathways, including (b) glutathione, (c) glycolysis, (d) pentose phosphate, and (e) purine biosynthesis. Z-scores were calculated from the log2 transformed FPKM values for each sample.

Supplementary Figure 5 Effects of short-term versus long-term glucose restriction and GLUT3 knockdown.

(a-c) Effect of glucose restricted conditions (0.45 g/L) and compared to standard conditions (4.5 g/L) for 48 hours on stemness markers in three BTIC models (a) T3691, (b) T387 and (c) T4121. Quantitative RT-PCR was then performed for stem cell markers, including SOX2, NES, and OLIG2, and differentiation markers, including GFAP and MBPF. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (T3691: SOX2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 11.262; NES, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.175; OLIG2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.728; GFAP, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 34.228; MBPF, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.103. T387: SOX2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.251; NES, P = 0.0029, t(4) = 5.385; OLIG2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.799; GFAP, P = 0.0008, t(4) = 7.509; MBPF, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 25.319. T4121: SOX2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 63.347; NES, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 30.664; OLIG2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 22.384; GFAP, P = 0.0065, t(4) = 4.266; MBPF, P = 0.0026, t(4) = 5.513.) (d-f) Effect of restricted glucose conditions (0.45 g/L) compared to standard conditions (4.5 g/L) for 7 days on stemness markers in three BTIC models (d) T3691, (e) T387, and (f) T4121. Quantitative RT-PCR was then performed for stem cell markers, including SOX2, NES, and OLIG2, and differentiation markers, including GFAP and MBPF. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. (T3691: SOX2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 10.369; NES, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 10.074; OLIG2, P = 0.0015, t(4) = 6.409; GFAP, P = 0.0015, t(4) = 6.436; MBPF, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.048. T387: SOX2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.883; NES, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.536; OLIG2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.481; GFAP, P = 0.0047, t(4) = 4.699; MBPF, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 7.217. T4121: SOX2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 35.185; NES, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 57.581; OLIG2, P = 0.0015, t(4) = 9.355; GFAP, P = 0.0017, t(4) = 6.183; MBPF, P = 0.0051, t(4) = 4.585.) (g) Knockdown of GLUT3 using two independent shRNAs decreased mRNA level of genes involved in purine synthesis in three BTIC models, T3691, T387 and T4121. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (T3691: shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0023, t(4) = 11.828; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0017, t(4) = 13.453; T387: shGLUT3-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.209; shGLUT3-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.923. T4121: shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0007, t(4) = 13.700; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 15.455.) (h) Quantitative RT-PCR assessment of PRPS1, PPAT, ADSL, ADSS, GMPS, and IMPDH1 mRNA levels in T3691 BTICs expressing shCont, shGLUT3-1, or shGLUT3-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (T3691: PRPS1, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0036, t(4) = 10.693; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0028, t(4) = 9.098; PPAT, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 7.292; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0041, t(4) = 5.102; ADSL, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0029, t(4) = 8.948; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0009, t(4) = 13.386; ADSS, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0056, t(4) = 6.619; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0100, t(4) = 7.136; GMPS, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0021, t(4) = 8.058. shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 11.836; IMPDH1, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0064, t(4) = 8.040; shGLUT3-2, P =0.0047, t(4) = 8.966.) (i) Quantitative RT-PCR assessment of PRPS1, PPAT, ADSL, ADSS, GMPS, and IMPDH1 mRNA levels in T387 BTICs expressing shCont, shGLUT3-1, or shGLUT3-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (T387: PRPS1, shGLUT3-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.053; shGLUT3-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.493; PPAT, shGLUT3-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.840; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 15.255; ADSL, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0013, t(4) = 7.966; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0018, t(4) = 7.371; ADSS, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0012, t(4) = 8.168, shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0020, t(4) = 7.184; GMPS, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 13.656, shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 11.689; IMPDH1, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0017, t(4) = 7.527; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0024, t(4) = 6.845.) (j) Quantitative RT-PCR assessment of PRPS1, PPAT, ADSL, ADSS, GMPS, and IMPDH1 mRNA levels in T4121 BTICs expressing shCont, shGLUT3-1, or shGLUT3-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (T4121: PRPS1, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 18.993; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 22.626; PPAT, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0030, t(4) = 8.595; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0015, t(4) = 8.029; ADSL, shGLUT3-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.242; shGLUT3-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.000; ADSS, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 8.626; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0007, t(4) = 9.225; GMPS, shGLUT3-1, P = 0.0015, t(4) = 10.968; shGLUT3-2, P = 0.0008, t(4) = 14.626; IMPDH1, shGLUT3-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 53.575, shGLUT3-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 61.720.) (k,l) Glutamine partially rescued defects in cell proliferation induced by glucose restriction. Two BTIC models (k) T3691 and (l) T4121 were treated with restricted glucose conditions (0.45 g/L) compared to standard conditions (4.5 g/L). 2 mM glutamine or 100 μM acetate was used to rescue glucose restriction separately. Cell viability was measured by CellTiter-Glo. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (T3691 BTICs: Day 3, glucose restricted, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 25.748; glucose restricted + glutamine, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 9.168; glucose restricted + acetate, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 25.762; Day 5, glucose restricted, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 26.061; glucose restricted + glutamine, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 25.288; glucose restricted + acetate, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 26.288. T4121 BTICs: Day 3, glucose restricted, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 13.688; glucose restricted + glutamine, P = 0.0043, t(10) = 3.676; glucose restricted + acetate, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 11.881; Day 5, glucose restricted, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 42.796; glucose restricted + glutamine, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 25.721; glucose restricted + acetate, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 39.037.)

Supplementary Figure 6 Nitrogen tracing in BTICs using [15N2]glutamine.

(a-f) Targeted mass spectrometry was used to examine the levels of (a,b) IMP, (c,d) AMP, and (e,f) GMP using cell lysates of BTICs and matched DGCs from patient-derived glioblastoma specimen T387 treated with media containing either 2 mM regular glutamine or 2 mM 15N2-glutamine, respectively, for 24 hours before harvesting.

Supplementary Figure 7 Transcription factor MYC regulates mRNA levels of purine synthesis pathway genes in BTICs.

(a-g) Knockdown of MYC using two independent shRNAs decreased mRNA levels of genes involved in purine synthesis in BTICs. Quantitative RT-PCR assessment of MYC, PRPS1, PPAT, ADSL, ADSS, GMPS, and IMPDH1 mRNA levels in T387 and T4121 BTICs expressing shCont, shMYC-1, or shMYC-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (a) MYC levels: T387: shMYC-1, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 14.853; shMYC-2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 17.277. T4121: shMYC-1, P = 0.0004, t(4) = 17.929; shMYC-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 22.822. (b) PRPS1 levels: T387: shMYC-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 26.097; shMYC-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 11.178. T4121: shMYC-1, P = 0.0063, t(4) = 9.693; shMYC-2, P = 0.0021, t(4) = 7.116. (c) PPAT levels: T387: shMYC-1, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 13.522; shMYC-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 21.005. T4121: shMYC-1, P = 0.0011, t(4) = 9.169; shMYC-2, P = 0.0014, t(4) = 8.675. (d) ADSL levels: T387: shMYC-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 23.201; shMYC-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.491. T4121: shMYC-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.244; shMYC-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 13.751. (e) ADSS levels: T387: shMYC-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.853; shMYC-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.784. T4121: shMYC-1, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 7.265; shMYC-2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 6.901. (f) GMPS levels: T387: shMYC-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.462; shMYC-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.212. T4121: shMYC-1, P = 0.0035, t(4) = 8.809; shMYC-2, P = 0.0234, t(4) = 3.256. (g) IMPDH1 levels: T387: shMYC-1, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 11.061; shMYC-2, P = 0.0007, t(4) = 8.687. T4121: shMYC-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 50.570; shMYC-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 39.171. (h-n) Overexpression of exogenous MYC upregulates mRNA levels of genes involved in purine synthesis pathway in BTICs. Quantitative RT-PCR assessment of PRPS1, PPAT, ADSL, ADSS, GMPS, and IMPDH1 mRNA levels in T387 and T4121 BTICs expressing empty vector (Vector) or MYC overexpression vector (Myc). All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (h) MYC levels: T387: p = 4.76e-05., t(4) = 18.750. T4121: p = 1.85e-06. t(4) = 42.371. (i) PRPS1 levels: T387: P = 0.0072, t(4) = 16.118. T4121: P = 0.0054, t(4) = 7.577. (j) PPAT levels: T387: P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.038. T4121: P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.734. (k) ADSL levels: T387: P = 0.0010, t(4) = 10.814. T4121: P = 0.0082, t(4) = 5.112. (l) ADSS levels: T387: P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.064. T4121: P = 0.0120, t(4) = 4.923. (m) GMPS levels: T387: P = 0.0054, t(4) = 5.487. T4121: P < 0.0001, t(4) = 31.383. (n) IMPDH1 levels: T387: P = 0.0004, t(4) = 14.926. T4121: P = 0.0027, t(4) = 6.588. (o,p) MYC regulates stemness markers in BTICs. Expression of MYC was knocked down using two non-overlapping shRNAs in (o) T387 and (p) T4121 BTICs. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed for precursor markers, including SOX2, NES, and OLIG2, and differentiation markers, including GFAP and MBPF. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (o) T387: SOX2, shRNA1, P = 0.0035, t(4) = 5.077; shRNA2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.675. NES, shRNA1, P = 0.0044, t(4) = 4.775; shRNA2, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 8.081. OLIG2, shRNA1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 30.207; shRNA2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 51.140. GFAP, shRNA1, P = 0.0008, t(4) = 7.698; shRNA2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 30.218. MBPF, shRNA1, P = 0.0007, t(4) = 7.748; shRNA2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.316. (p) T4121: SOX2, shRNA1, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 8.549; shRNA2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.691. NES, shRNA1, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 7.237; shRNA2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.479. OLIG2, shRNA1, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.169; shRNA2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.191. GFAP, shRNA1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.957; shRNA2, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 7.318. MBPF, shRNA1, P = 0.0021, t(4) = 5.865; shRNA2, P = 0.0044, t(4) = 4.786. (q,r) MYC induces stemness markers in DGCs. MYC was transduced into in (o) T387 and (p) T4121 DGCs using a lentiviral construct. An empty lentiviral vector was used as a negative control. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed for precursor markers (SOX2, NES, and OLIG2), and differentiation markers (GFAP and MBPF). All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (q) T387: SOX2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 11.187; NES, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.998; OLIG2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.315; GFAP, P = 0.0004, t(4) = 9.214; MBPF, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 10.481. (r) T4121: SOX2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.782; NES, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 8.348; OLIG2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 23.285; GFAP, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.848; MBPF, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 23.382.

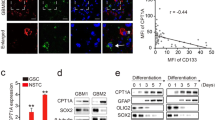

Supplementary Figure 8 Purine pathway gene expression analysis by subtype from TCGA datasets.

(a-c) The expression levels of (a) individual precursor marker mRNAs (OLIG2, MYC, and SOX2), (b) individual purine synthesis pathway mRNAs (IMPDH1, PRPS1, PPAT, GMPS, ADSL, and ADSS), and (c) purine pathway expression signature based on KEGG definition, from the TCGA dataset were plotted by four subtypes (Classical, Mesenchymal, Neural, and Proneural) as designated by the Verhaak 2010 paradigm. (d-f) PPAT, ADSS, and IMPDH1 are upregulated in BTICs. H3K27ac ChIP-seq enrichment plots centered at the gene locus for (d) ADSS, (e) IMPDH1, and (f) PPAT were displayed. Enrichment is shown for three matched pairs of DGCs and BTICs from patient-derived glioblastoma specimens. H3K27ac ChIP-seq data were downloaded from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE54047. (g-i) qRT-PCR quantification of ADSS, IMPDH1, or PPAT mRNA levels in three patient-derived BTIC models during differentiation. BTICs derived from three primary human glioblastoma specimens (T3691, T387, T4121) were treated with serum to induce differentiation, with time points taken at 2, 4, and 6 days. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (ADSS: T3691, 2d, P = 0.7400, t(4) = 0.353; 4d, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 10.524; 6d, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 10.049; T387, 2d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 24.171; 4d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 28.101; 6d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 29.636; T4121, 2d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.710; 4d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.975; 6d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 24.548. IMPDH1: T3691, 2d, P = 0.0133, t(4) = 3.996; 4d, P = 0.0024, t(4) = 6.522; 6d, P = 0.0029, t(4) = 6.237; T387, 2d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.792; 4d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 22.904; 6d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 22.964; T4121, 2d, P = 0.0105, t(4) = 4.553; 4d, P = 0.0049, t(4) = 8.337; 6d, P = 0.0017, t(4) = 6.913. PPAT: T3691, 2d, P = 0.0200, t(4) = 4.784; 4d, P = 0.0033, t(4) = 7.025; 6d, P = 0.0035, t(4) = 7.681; T387, 2d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 21.370; 4d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 24.175; 6d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 25.004; T4121, 2d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.839; 4d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.865; 6d, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.083.)

Supplementary Figure 9 Confirmation and reconstitution of ADSL, GMPS or PRPS1 knockdown.

(a) Confirmation of ADSL knockdown effect in BTICs (T387 and T4121) (b) Confirmation of GMPS knockdown effect in BTICs (T387 and T4121). (c) Confirmation of PRPS1 knockdown effect in BTICs (T387 and T4121). (d-f) Reconstitution of shRNA-mediated knockdown of purine synthesis genes in BTICs. Expression constructs for human ADSL, GMPS< and PRPS1, which were resistant to the respective shRNAs, were used to reconstitute the expression of corresponding genes in two BTIC models, T387 and T4121. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (d) ADSL: T387, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.560, shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.701; shADSL-1 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.428; shADSL-2 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.765; T4121, shADSL-1, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 11.904, shADSL-2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 11.571; shADSL-1 + ADSL, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 9.588; shADSL-2 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 29.885. (e) GMPS: T387, shGMPS-1, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.301, shGMPS-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 11.375; shGMPS-1 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 22.867; shGMPS-2 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 58.042; T4121, shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.121, shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.955; shGMPS-1 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 4.795; shGMPS-2 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.223. (f) PRPS1: T387, shPRPS1-1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 10.059, shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.448; shPRPS1-1 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 32.778; shPRPS1-2 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 84.438; T4121, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.042, shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.371; shPRPS1-1 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.407; shPRPS1-2 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 29.308. (g-i) Cell viability was measured on T387 BTICs with reconstitution of (g) ADSL, (h) GMPS, or (i) PRPS1 upon targeting each gene. BTICs expressing shCont were used as positive controls, and BTICs expressing shRNA targeting each gene without reconstitution were used as negative controls. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (g) ADSL: 3d, shCont vs. shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 11.702; shCont vs. shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 12.057; shADSL-1 vs. shADSL-1 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 12.419; shADSL-2 vs. shADSL-2 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 23.708; 5d, shCont vs. shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 11.940; shCont vs. shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 12.030; shADSL-1 vs. shADSL-1 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 50.707; shADSL-2 vs. shADSL-2 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 12.524. (h) GMPS: 3d, shCont vs. shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 21.323; shCont vs. shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 20.689; shGMPS-1 vs. shGMPS-1 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 19.455; shGMPS-2 vs. shGMPS-2 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 27.714; 5d, shCont vs. shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 21.273; shCont vs. shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 21.327; shGMPS-1 vs. shGMPS-1 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 45.018; shGMPS-2 vs. shGMPS-2 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 18.834. (i) PRPS1: 3d, shCont vs. shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 21.930; shCont vs. shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 22.394; shPRPS1-1 vs. shPRPS1-1 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 16.273; shPRPS1-2 vs. shPRPS1-2 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 27.214; 5d, shCont vs. shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 24.397; shCont vs. shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 25.813; shPRPS1-1 vs. shPRPS1-1 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 17.896; shPRPS1-2 vs. shPRPS1-2 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 16.070. (j-l) Cell viability was measured on T4121 BTICs with reconstitution of (j) ADSL, (k) GMPS, or (l) PRPS1 upon targeting each gene. BTICs expressing shCont were used as positive controls, and BTICs expressing shRNA targeting each gene without reconstitution were used as negative controls. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (j) ADSL: 3d, shCont vs. shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 21.756; shCont vs. shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 20.821; shADSL-1 vs. shADSL-1 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 20.792 shADSL-2 vs. shADSL-2 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 24.815; 5d, shCont vs. shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 17.779; shCont vs. shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 17.833; shADSL-1 vs. shADSL-1 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 14.576; shADSL-2 vs. shADSL-2 + ADSL, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 9.860. (k) GMPS: 3d, shCont vs. shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 24.485; shCont vs. shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 24.741; shGMPS-1 vs. shGMPS-1 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 20.847; shGMPS-2 vs shGMPS-2 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 26.123; 5d, shCont vs. shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 19.968; shCont vs. shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 20.034; shGMPS-1 vs. shGMPS-1 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 13.139; shGMPS-2 vs. shGMPS-2 + GMPS, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 16.020. (l) PRPS1: 3d, shCont vs. shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 14.668; shCont vs. shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 13.888; shPRPS1-1 vs. shPRPS1-1 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 25.521; shPRPS1-2 vs. shPRPS1-2 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 32.771; 5d, shCont vs. shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 15.793; shCont vs. shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 15.749; shPRPS1-1 vs shPRPS1-1 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 15.179; shPRPS1-2 vs. shPRPS1-2 + PRPS1, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 16.676. (m-r) Attenuation of purine synthesis pathway genes decreases levels of precursor markers. The expression levels of three purine synthesis pathway genes (ADSL, GMPS, and PRPS1) were knocked down using shRNAs in (m-o) T387 and (p-r) T4121 BTICs. Two independent shRNAs were used for each gene, and shCont was used as a control. Quantitative RT-PCR assessment was performed for precursor markers (SOX2, NES, and OLIG2), and differentiation markers (GFAP and MBPF). All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (m) shADSL/T387: SOX2, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.673; shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(10) = 17.606. NES, shADSL-1, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 11.146; shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.397. OLIG2, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 58.604; shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 79.446. GFAP, shADSL-1, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 8.312; shADSL-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.230. MBPF, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 28.772; shADSL-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.936. (n) shGMPS/T387: SOX2, shGMPS-1, p = 0.0017 P < 0.0001, t(4) = 6.174; shGMPS-2, P = 0.0022, t(4) = 5.770. NES, shGMPS-1, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 8.178; shGMPS-2, P = 0.0004, t(4) = 9.273. OLIG2, shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 21.918; shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.266. GFAP, shGMPS-1, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 8.254; shGMPS-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.016. MBPF, shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 19.169; shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.426. (o) shPRPS1/T387: SOX2, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.687; shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.160. NES, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.845; shPRPS1-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 16.453. OLIG2, shPRPS1-1, P = 0.0008, t(4) = 7.737; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 8.555. GFAP, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.062; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 7.229. MBPF, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 18.115; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 11.449. (p) shADSL/T4121: SOX2, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 21.903; shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 21.559. NES, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.181; sh-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.622. OLIG2, shADSL-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 35.077; shADSL-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 33.981. GFAP, shADSL-1, P = 0.0017, t(4) = 6.204; shADSL-2, P = 0.0067, t(4) = 4.227. MBPF, shADSL-1, P = 0.0005, t(4) = 8.531; shADSL-2, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 10.723. (q) shGMPS/T4121: SOX2, shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 24.236; shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 35.825. NES, shGMPS-1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.719; shGMPS-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.040. OLIG2, shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 15.920; shGMPS-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.743. GFAP, shGMPS-1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 10.097; shGMPS-2, P = 0.0011, t(4) = 7.052. MBPF, shGMPS-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 14.167; shGMPS-2, P = 0.0006, t(4) = 8.057. (r) shPRPS1/T4121: SOX2, shPRPS1-1, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 9.883; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0010, t(4) = 7.120. NES, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 13.532; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0008, t(4) = 7.601. OLIG2, shPRPS1-1, P = 0.0002, t(4) = 10.928; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0003, t(4) = 10.153. GFAP, shPRPS1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.580; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0001, t(4) = 12.366. MBPF, shPRPS1-1, P = 0.0108, t(4) = 3.658; shPRPS1-2, P = 0.0024, t(4) = 5.659.

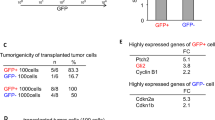

Supplementary Figure 10 Purine synthesis enzymes are dispensable in DGCs.

(a) Cell viability of T387 and T4121 DGCs expressing non-targeting control shRNA (shCont), shADSL-1, or shADSL-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (T387: shADSL-1, 3d, P = 0.0898, t(10) = 1.901; 5d, P = 0. 0.6953, t(10) = 0.405. shADSL-2, 3d, P = 0. 0.2007, t(10) = 1.381; 5d, P = 0.0.3285, t(10) = 1.033. T4121: shADSL-1, 3d, P = 0. 0.7437, t(10) = 0.336; 5d, P = 0.5498, t(10) = 0.619. shADSL-2, 3d, P = 0.0.4010, t(10) = 0.877; 5d, P = 0. 0.1005, t(10) = 1.857.) (b) Cell viability of T387 and T4121 DGCs expressing shCont, shGMPS-1, or shGMPS-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (T387: shGMPS-1, 3d, P = 0. 0.5411, t(10) = 0.648; 5d, P = 0. 5498, t(10) = 0.619. shGMPS-2, 3d, P = 0. 5308, t(10) = 0.665; 5d, P = 0. 1243, t(10) = 1.786. T4121: shGMPS-1, 3d, P = 0. 1611, t(10) = 1.598; 5d, P = 0. 2542, t(10) = 1.261. shGMPS-2, 3d, P = 0. 1765, t(10) = 1.532; 5d, P = 0. 1334, t(10) = 1.735.) (c) Cell viability of T387 and T4121 DGCs expressing shCont, shPRPS1-1, or shPRPS1-2. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; n = 6 independent experiments per group. (T387: shPRPS1-1, 3d, P = 0. 6128, t(10) = 0.509; 5d, P = 0. 6473 t(10) = 0.433. shPRPS1-2, 3d, P = 0. 1689, t(10) = 1.483; 5d, P = 0. 7176, t(10) = 0.372. T4121: shPRPS1-1, 3d, P = 0. 9627, t(10) = 0.048; 5d, P = 0. 9848, t(10) = 0.019. shPRPS1-2, 3d, P = 0. 7391, t(10) = 0.342; 5d, P = 0. 1960, t(10) = 1.385.)

Supplementary Figure 11 In vivo impact of targeting purine synthesis enzymes on proliferation, apoptosis and stemness.

(a) Representative images of immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of cross-sections of mouse brains harvested on day 18 after transplantation of T387 BTICs expressing shCont, shADSL-1, or shADSL-2. Ki-67, cleaved Caspase-3, and SOX2 were employed as markers of proliferation, apoptosis, and stemness respectively. Each image was representative for at least 3 similar experiments. (b) Representative images of IHCstaining of cross-sections of mouse brains harvested on day 18 after transplantation of T387 BTICs expressing shCont, shGMPS-1, or shGMPS-2. Each image was representative for at least 3 similar experiments. (c) Representative images of IHC staining of cross-sections of mouse brains harvested on day 18 after transplantation of T387 BTICs expressing shCont, shPRPS1-1, or shPRPS1-2. Each image was representative for at least 3 similar experiments.

Supplementary Figure 12 Purine synthesis regulates in vivo BTIC tumorigenesis in an immunocompetent mouse model.

(a-c) Successful targeting of three purine synthetic genes: (a) Adsl, (b) Gmps, and Prps1, in the murine GL261 glioma line was confirmed by RT-PCR. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; **, P < 0.01; n = 3 independent experiments per group. Data were presented as median ± s.e.m. (shAdsl-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 22.059; shAdsl-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.764. shGmps-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 20.040; shGmps-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 17.503. shPrps1-1, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 61.767; shPrps1-2, P < 0.0001, t(4) = 30.503.) (d-f) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of MHC-matched B6 immunocompetent mice bearing intracranial glioma 261 (GL261) BTICs, transduced with shCont, shAdsl, shGmps, or shPrps1 are displayed. For each target, two, non-overlapping shRNAs were used. n = 5 animals per group. Statistical analysis was performed using log-rank test. **, p < 0.01. (shAdsl: P = 0.0002; shGmps: P < 0.0001; shPrps1: P = 0.0001.) (g-i) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin stained cross-sections of B6 mouse brains harvested on day 18 after transplantation of GL216 BTICs expressing shCont, shAdsl-1, shAdsl-2, shGmps-1, shGmps-2, shPrps1-1, or shPrps1-2 are shown. Scale bar, 2 mm. Each image was representative for at least 3 similar experiments.

Supplementary Figure 13 Purine synthesis enzymes are expressed in non-G-CIMP gliomas.

(a) Investigation of purine pathway gene expression in the pan-glioma TCGA cohort demonstrates enrichment in high grade glioma. (b) Gene set enrichment analysis reveals significant positive correlation of the purine metabolic signature with regulation of cell cycle and transcriptional activity. (c-f) Survival analysis of the Freije high-grade glioma dataset for PRPS1, ADSL, ADSS, and GMPS. All statistical analyses were performed using log-rank test. (PRPS1low, n = 44; PRPS1high, n = 41; P = 0.0854. ADSLlow, n = 43; ADSLhigh, n = 42; P = 0.2701. ADSSlow, n = 43; ADSShigh, n = 42; P = 0.9828. GMPSlow, n = 51; GMPShigh, n = 34; P = 0.0145.) (g-j) Survival analysis of the Phillips high-grade glioma dataset for PRPS1, ADSL, GMPS, and IMPDH. All statistical analyses were performed using log-rank test. (PRPS1low, n = 39; PRPS1high, n = 38; P = 0.3408. ADSLlow, n = 37; ADSLhigh, n = 38; P = 0.2416. GMPSlow, n = 52; GMPShigh, n = 25; P < 0.0001. IMPDH1low, n = 39; IMPDH1high, n = 38; P = 0.8485.) (k,l) Survival analysis of the TCGA glioblastoma for PRPS1 and GMPS. All statistical analyses were performed using log-rank test. (PRPS1low, n = 244; PRPS1high, n = 237; P = 0.098. GMPSlow, n = 230; GMPShigh, n = 251; P = 0.3408.) (m-r) Survival analysis of the REMBRANDT dataset for 6 enzymes in the purine synthesis pathway. All statistical analyses were performed using log-rank test. (PRPS1low, n = 254; PRPS1high, n = 255; P = 0.2029. PPATlow, n = 254; PPAThigh, n = 255; P = 0.0002. ADSLlow, n = 254; ADSLhigh, n = 255; P = 0.0063. ADSSlow, n = 254; ADSShigh, n = 255; P < 0.0001. GMPSlow, n = 254; GMPShigh, n = 255; P < 0.0001. IMPDH1low, n = 254; IMPDH1high, n = 255; P < 0.0001.)

Supplementary Figure 14 Proposed model of purine biosynthesis in BTICs.

BTICs upregulate GLUT3 to hijack the neuronal survival mechanism to compete for glucose in a dynamic microenvironment. The increased carbon influx is channeled to the synthesis of purine nucleotides, mediated by the transcriptional factor MYC. Elevated levels of purine nucleotides promote BTIC maintenance through numerous mechanisms, including DNA synthesis, self-renewal and tumorigenecity, and signaling pathways.

Supplementary Figure 15 Full-length Western blots.

Full-length Western blots for cropped images in Fig. 1g, 3d, 3i, 3k, 4a, 4b, 4k, 4l, and Supplementary Fig. 9a-c.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–15 and Supplementary Table 1 (PDF 3879 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Yang, K., Xie, Q. et al. Purine synthesis promotes maintenance of brain tumor initiating cells in glioma. Nat Neurosci 20, 661–673 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4537

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4537

This article is cited by

-

G6PD maintains the VSMC synthetic phenotype and accelerates vascular neointimal hyperplasia by inhibiting the VDAC1–Bax-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis pathway

Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters (2024)

-

Threonine fuels glioblastoma through YRDC-mediated codon-biased translational reprogramming

Nature Cancer (2024)

-

An intrinsic purine metabolite AICAR blocks lung tumour growth by targeting oncoprotein mucin 1

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

Lysine catabolism reprograms tumour immunity through histone crotonylation

Nature (2023)

-

GAP43-dependent mitochondria transfer from astrocytes enhances glioblastoma tumorigenicity

Nature Cancer (2023)