Abstract

Atomically thin two-dimensional materials have emerged as promising candidates for flexible and transparent electronic applications. Here we show non-volatile memory devices, based on field-effect transistors with large hysteresis, consisting entirely of stacked two-dimensional materials. Graphene and molybdenum disulphide were employed as both channel and charge-trapping layers, whereas hexagonal boron nitride was used as a tunnel barrier. In these ultrathin heterostructured memory devices, the atomically thin molybdenum disulphide or graphene-trapping layer stores charge tunnelled through hexagonal boron nitride, serving as a floating gate to control the charge transport in the graphene or molybdenum disulphide channel. By varying the thicknesses of two-dimensional materials and modifying the stacking order, the hysteresis and conductance polarity of the field-effect transistor can be controlled. These devices show high mobility, high on/off current ratio, large memory window and stable retention, providing a promising route towards flexible and transparent memory devices utilizing atomically thin two-dimensional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The remarkable properties of graphene, such as high carrier mobility, thermal conductivity, mechanical flexibility and optical transparency, make it a highly promising material for future electronics1,2. The ongoing development of graphene electronics has been accompanied by increasing interest in other two-dimensional (2D) layered materials with different electronic properties, which can be combined with graphene into other layered heterostructures3,4,5,6. For instance, insulating hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) has emerged as an excellent substrate for graphene, yielding graphene devices with improved mobility and lower disorder compared with more conventional dielectrics4. Furthermore, hBN is atomically flat and, thus, it can serve as a uniform tunnelling barrier that allows perfectly planar charge injection7. Semiconducting molybdenum disulphide (MoS2), another 2D material, shows a transition from an indirect band gap of 1.3 eV in the bulk to a direct band gap of 1.8 eV for a monolayer6. MoS2 field-effect transistors (FETs) with high mobility (200 cm2 V−1 s−1) and an on/off ratio of ~108 have also been recently reported5. Such excellent electrical properties, high transparency and flexibility, altogether make these 2D materials perfect candidates for flexible electronics. Moreover, rapid development in the synthesis of 2D materials is improving prospects for mass production and large-scale integration of 2D electronic materials1,8,9,10,11,12. Multi-stacking of atomically thin 2D materials enables vertical integration and use of conventional lithography process. Recently, heterostructure of 2D materials produced by multi-stacking process opened up a route to make new types of material platforms for high-performance devices4,13,14,15.

A number of reports have utilized graphene or graphene oxide in non-volatile memory devices, such as an FET channel, a charge-trapping layer or an electrode16,17,18,19,20,21,22. It was shown that the large hysteresis in the gate characterization curves of graphene FETs (GFETs) can be applied for memory device operation23. It was also demonstrated that this hysteresis arises due to trapped charge in the oxide dielectric layer24. However, the relatively slow dynamics and poor controllability of the trap density in these graphene memory devices require further improvement for realistic applications. Furthermore, insulator (or tunnel barrier) and channel material with band gap, which should be ultrathin and stable, have been required for flexible and transparent memory applications. In this sense, the 2D materials, such as hBN and MoS2, can be great candidates thanks to their superior electrical and mechanical properties4,7,25.

Here we demonstrate memory devices fabricated entirely from stacked 2D materials. We fabricated two types of 2D heterostructured memory devices, which show a significant hysteresis and memory performance thanks to the charge-trapping characteristics of graphene and MoS2. One of the two types of the memory devices was fabricated with graphene as the FET channel, hBN as the tunnel barrier and MoS2 as the charge-trapping layer (denoted as GBM) and the other with MoS2 as the FET channel, hBN as the tunnel barrier and graphene as the charge trapping layer (denoted as MBG). These ultrathin heterostructured memory devices (thinner than 10 nm) consisting of 2D materials has great potential for further miniaturization, application in low-cost electronics and flexible memory device applications, especially in the future mobile devices requiring embedded memories integrated into multi-functional system-on-a-chip.

Results

Memory characteristics of heterostructured devices

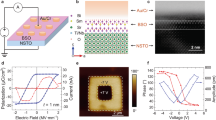

Heterostructured devices were fabricated by stacking 2D materials, which are prepared by mechanical exfoliation (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. S1) In the case of GBM devices, to verify the effect of charge trapping in MoS2, the graphene sample was cut into two regions—one region with and the other without MoS2. Figure 1a shows the circuit diagram of a fabricated GBM device. Figure 1b shows optical micrographs of GBM and MBG devices. In Fig. 1b, a graphene/hBN device without MoS2 is denoted as GB. Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S1 summarize the Raman spectra and photoluminescence (PL) of graphene, hBN, MoS2 layers and thickness of each layer of the devices fabricated for this study.

Figure 2a shows the transfer curve of one device (GBM3), with an hBN layer of 6 nm thick and a MoS2 layer of 5 nm thick. The position of the Dirac point, corresponding to the minimum conductivity, shifts by more than 20 V and exhibits a large hysteresis when the direction of the gate voltage sweep is reversed. This remarkable hysteresis is related to underlying MoS2 layer, as there is no appreciable hysteresis in the transfer curve of GB3, a graphene device on the same graphene sample as GBM3 but without underlying MoS2 layer, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2a. The field-effect mobility of graphene in GBM3 is 4,200 cm2 V−1 s−1, which is lower than reported in graphene on hBN4. This mobility degradation is likely due to the presence of a small number of bubbles and wrinkles, as observed in the atomic force microscopy images of Supplementary Fig. S3, which can introduce charge inhomogeneity26. However, as hysteresis is not observed in all the GB devices, it is obvious that the existence of underlying MoS2 layer gives rise to the hysteresis in transfer curve of the GBM devices. Even when different voltage sweep rates are applied, no appreciable differences are noted in transfer curves of GBM devices as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. This indicates that the hysteresis of the transfer curve is not caused by the captured molecules, such as a thin layer of water, at the interface of graphene/hBN23.

(a) Transfer curve (ID−VG) and (b) retention performance of the GBM3 device with hBN of 6 nm and MoS2 of 5 nm. The inset of a shows a transfer curve of GB3. For GBM devices, all the transfer curves in the main text were obtained at VD=100 mV and medium sweep rate of 23 V s−1. The retention of b was measured at VG=15 V with a pulse of +40 V (red triangle) and −40 V (blue circle), pulse width of 1 ms and VD=100 mV. (c) Transfer curve and (d) retention performance of the MBG1 device with hBN of 12 nm, MoS2 of three layers and graphene of two layers. The inset of c shows a transfer curve of the same device when graphene was used for gating. For MBG devices, all the measurement of transfer curve in the main text was obtained at VD=50 mV and medium sweep rate of 23 V s−1. The retention of d was measured at VG=0 V with pulse of −15 V (violet circle) and +15 V (orange triangle), pulse width of 100 μs and VD=50 mV.

The observed large gate hysteresis can be utilized for a non-volatile memory-device operation employing the MoS2 layer as a floating gate. The retention of trapped charge by the MoS2 layer is shown in Fig. 2b. The current (ID) in graphene was measured at VG=15 V when gate voltages of ±40 V with pulse width of 1 ms were applied. Two states with different currents can be defined as ‘trap’ and ‘release’ states. The retention performance shows that trapped charge in the MoS2 layer is maintained without loss of charge. Although Irelease/Itrap is low (~2), most of the GBM devices measured in this work exhibit similar retention characteristics regardless of thicknesses of MoS2 charge-trap layer and hBN tunnelling barrier. This charge trapping can be preserved over 100 cycles as shown in the endurance characteristic (Supplementary Fig. S5a). We observed that even GBM devices with monolayer MoS2 exhibit charge-trapping characteristics, resulting in large hysteresis and a good trapped charge-retention property (Supplementary Fig. S6a,b). Most memory devices relying on charge trapping suffer from problems related to charge retention, such as loss of charge by back-tunnelling, injection of carriers of the opposite type or redistribution of charge in defects27. In our multi-stack devices, however, the unique device geometry utilizing a high tunnelling barrier and defect-free crystallinity of 2D crystals provides a solution to circumvent these technical issues.

As single-layer graphene has zero band gap, GFETs have an intrinsically small on/off ratio. To overcome this in FET devices, novel design concepts such as graphene barristor have been proposed28. For memory devices, a more reasonable solution is the use of 2D material with large band gap. Therefore, we fabricated devices with a reversed stacking order, in which single or multilayer MoS2 was employed as a channel and graphene was employed as the charge-trapping layer. The transfer curve of the reverse structure MBG1 device exhibited large hysteresis of ΔV~15 V and high on/off current ratio of 104 as shown in Fig. 2c. Similar to GBM devices, different voltage sweep rates showed no appreciable changes in transfer curves of MBG devices as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4d. When graphene was used as a gate electrode, the transfer curve of MBG1 device showed no hysteresis as shown in the inset of Fig. 2c. Moreover, when graphene is grounded, hysteresis of MBG1 device disappeared because of release of the trapped charge from graphene (Supplementary Fig. S7b,d). These results demonstrate that the hysteresis of the MBG device is due to charge trapped in the graphene layer rather than at interfaces between the layers. As a result, good retention and endurance were observed (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. S5b). High on/off ratio was maintained over 1,400 s. The carrier mobility of MoS2 in MBG devices ranged from 10 to 40 cm2 V−1 s−1, depending on the thickness of MoS2. Even though the carrier mobility of MoS2 is smaller than that of graphene, MBG heterostructure devices should be useful for flexible memory applications requiring the high on/off current ratio. As organic memories are being studied as leading contending devices for future flexible device application, we compared the performances of our GBM and MBG to those of reported organic memories (Supplementary Table S2)29,30. Compared with organic memories, the heterostructured memory devices fabricated in our study exhibited better performances with advantages of miniaturization, carrier mobility, on/off current ratio, retention and power saving. In addition, the heterostructure memory devices also showed superior stability at high temperature (Supplementary Figs S8 and S9), which implies that these devices can be used in harsh conditions.

Effect of charge-trapping layers

Figure 3 shows proposed energy band diagrams of the tested devices in the flat band state (Fig. 3a, with no contact between layers and no applied bias) and in the carrier transfer state (Fig. 3b). The work function and electron affinity of MoS2 are 4.6–4.9 eV and 4.2 eV, respectively31,32. hBN has larger band gap (5.2–5.9 eV) and smaller electron affinity (2–2.3 eV)7,33. Thererefore, the barrier heights for electron and hole tunnelling through hBN (Φe and Φh) are 2.3–2.6 eV and 2.7–3.4 eV, respectively. The work function of a charge-neutral monolayer graphene is 4.6 eV, and it can be further tuned by external electric field34. In the case of GBM, when graphene is influenced by electrical field, carrier density in graphene can be calculated by n=Cox/e(VG−V0), where Cox and e are capacitance of oxide layer and charge of electron, and V0 is the gate voltage corresponding to the charge neutrality point. The shift of Fermi level can then be expressed by EF=sgn(n)ħυF , where, υF and ħ are Fermi velocity and Planck’s constant, respectively. With SiO2 thickness of 280 nm and hBN thickness of 10 nm, Cox/e ~7.5 × 1010 cm−2 V−1 is obtained. For the gate voltages of −40 V and +40 V in GBM3, the calculated Fermi level shifts of single-layer grapheme (SLG) (EF) are −0.19 eV and +0.22 eV, respectively. For this, proximity in energy to conduction (eVp) or valence band (eVn) of MoS2 should be considered, because tunnelling probability increases with a line-up of energy states in MoS2 and graphene. Although these Fermi level shifts can lower the barrier height for tunnelling (Fig. 3b), the resulting tunnel barrier height is still too high for Schottky thermal emission. Therefore, it is inferred that the main mechanism of charge transfer through hBN is via quantum tunnelling, which can occur in oxide layers thinner than 6 nm27 (Supplementary Fig. S10). At small gate voltage, the tunnelling current exponentially increases with decreasing hBN thickness, leading to increasing charge injection for trapping7. This trend is further supported by the experimental observation that the hysteresis of the transfer characteristic curves in GBM and MBG is larger for thinner hBN barriers (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S11). Moreover, the change in Fermi level (EF) in graphene alters the shape of barrier more significantly for a thinner tunnelling barrier, increasing tunnelling current through thinner hBN13. We also note that the tunnelling injection of carriers can be unipolar as indicated in Fig. 3b, electrons in n-doped graphene can be transferred to MoS2 for VG>0, while holes in p-doped graphene can hardly move to MoS2 for VG<0. The electron tunnelling behaviour through hBN will be explained in detail later. Although carrier transport in the floating gate MoS2 cannot be measured directly, it is considered that the transferred electrons into MoS2 are mobile and stay stably in the conduction band, as the grounded charge-trapping layer of MoS2 causes no hysteresis (Supplementary Fig. S7c), and characteristics of programming and erasing are reproducible as shown in Figs 2 and 4. In MBG devices, graphene acts as a floating gate, which can trap or eject electrons depending on gate voltage as shown in Fig. 3c. When gate voltage is positive in a trapping process, electrons in MoS2 can be pulled and transferred to graphene by tunnelling. The transferred electrons (orange color) can be trapped in graphene. When gate voltage becomes negative in a releasing process, the trapped electrons can be transferred to MoS2, because the negative gate voltage pushes electrons. The Fermi level of graphene is higher than Dirac point in the initial stage of releasing process, because the trapped electrons occupy the energy states over the Dirac point. As the trapped electrons keep transferring to MoS2, the Fermi level of graphene will decrease quickly and become close to the Dirac point. Then, electron-hole recombination probably occurs, resulting in fast removal of the trapped electrons. This also can be supported by the results that trapped charges are released and give rise to no hysteresis when the floating gates are grounded (Supplementary Fig. S7d).

, where, υF and ħ are Fermi velocity and Planck’s constant, respectively. With SiO2 thickness of 280 nm and hBN thickness of 10 nm, Cox/e ~7.5 × 1010 cm−2 V−1 is obtained. For the gate voltages of −40 V and +40 V in GBM3, the calculated Fermi level shifts of single-layer grapheme (SLG) (EF) are −0.19 eV and +0.22 eV, respectively. For this, proximity in energy to conduction (eVp) or valence band (eVn) of MoS2 should be considered, because tunnelling probability increases with a line-up of energy states in MoS2 and graphene. Although these Fermi level shifts can lower the barrier height for tunnelling (Fig. 3b), the resulting tunnel barrier height is still too high for Schottky thermal emission. Therefore, it is inferred that the main mechanism of charge transfer through hBN is via quantum tunnelling, which can occur in oxide layers thinner than 6 nm27 (Supplementary Fig. S10). At small gate voltage, the tunnelling current exponentially increases with decreasing hBN thickness, leading to increasing charge injection for trapping7. This trend is further supported by the experimental observation that the hysteresis of the transfer characteristic curves in GBM and MBG is larger for thinner hBN barriers (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S11). Moreover, the change in Fermi level (EF) in graphene alters the shape of barrier more significantly for a thinner tunnelling barrier, increasing tunnelling current through thinner hBN13. We also note that the tunnelling injection of carriers can be unipolar as indicated in Fig. 3b, electrons in n-doped graphene can be transferred to MoS2 for VG>0, while holes in p-doped graphene can hardly move to MoS2 for VG<0. The electron tunnelling behaviour through hBN will be explained in detail later. Although carrier transport in the floating gate MoS2 cannot be measured directly, it is considered that the transferred electrons into MoS2 are mobile and stay stably in the conduction band, as the grounded charge-trapping layer of MoS2 causes no hysteresis (Supplementary Fig. S7c), and characteristics of programming and erasing are reproducible as shown in Figs 2 and 4. In MBG devices, graphene acts as a floating gate, which can trap or eject electrons depending on gate voltage as shown in Fig. 3c. When gate voltage is positive in a trapping process, electrons in MoS2 can be pulled and transferred to graphene by tunnelling. The transferred electrons (orange color) can be trapped in graphene. When gate voltage becomes negative in a releasing process, the trapped electrons can be transferred to MoS2, because the negative gate voltage pushes electrons. The Fermi level of graphene is higher than Dirac point in the initial stage of releasing process, because the trapped electrons occupy the energy states over the Dirac point. As the trapped electrons keep transferring to MoS2, the Fermi level of graphene will decrease quickly and become close to the Dirac point. Then, electron-hole recombination probably occurs, resulting in fast removal of the trapped electrons. This also can be supported by the results that trapped charges are released and give rise to no hysteresis when the floating gates are grounded (Supplementary Fig. S7d).

Energy band diagrams of (a) flat band state (χ: electron affinity, Eg: band gap, W: work function, ф: tunnelling barrier and eVp (eVn): difference in energy between conduction band (or valence band) of MoS2 and Fermi level of graphene; M, B, G, e and h indicate MoS2, hBN, graphene, electron and hole, respectively) and (b) carrier transfer state of GBM device. When VG>0 is applied, electrons can be transferred from graphene to MoS2 by tunnelling through the hBN barrier. On the other hand, holes in graphene cannot be transferred to MoS2 at VG<0. (c) Energy band diagrams of carrier transfer state of MBG device. In trapping process of VG>0, electrons can be trapped in graphene by tunnelling from MoS2. In releasing process of VG<0, the trapped electrons in graphene move back to MoS2 at initial stage. As the Fermi level of graphene is further reduced and below Dirac point, the trapped electrons can recombine with holes generated in graphene.

(a) Transfer curve of GBM2, which has hBN of 11 nm and MoS2 of 3.3 nm. The inset of a shows the transfer curve of GB2 in the same sample. (b) Transfer curves of GBM2 measured with various pulse widths of VG=±80 V. The filled and blank symbols represent the values measured with +80 V and −80 V, respectively. (c) Gate voltages, which show the same ID of 78 nA, and calculated charge-trapping rate of GBM2 as a function of gate pulse width. The charge-trapping rate (dNtrap/dt) is estimated by gate shift ΔVS and the pulse width Δt. (d) Transfer curves of MBG1 measured with various pulse widths of VG=±30 V. The filled and blank symbols represent the values measured with +30 V and −30 V, respectively. (e) Gate voltages, which show the same ID of 50 nA, and calculated charge-trapping rate of MBG1 as a function of gate pulse width.

Charging the floated MoS2 gate changes the transfer characteristic of the GBM memories significantly. In particular, when a thick MoS2 layer is used (GBM2), the GFET exhibits a unipolar p-type behaviour, as shown in Fig. 4a. Similar unipolar behaviour was reported in graphene covered with water layer or in doped graphene by metallic oxide, and graphene dual dielectric memory23,35,36. To verify that the unipolar behaviour is due to charge trapping in the MoS2 layer, we employed two devices fabricated on a same graphene flake without MoS2-trapping layer, but one on hBN (GB2) and the other on SiO2 (GS2) (Supplementary Fig. S12a). As seen in inset of Fig. 4a, ambipolar behaviour without hysteresis was observed in GB2 (device without MoS2 layer). On the other hand, GS2 (device without hBN substrate nor MoS2) exhibits moderate hysteresis (shift less than 5 V), presumably due to adsorbed molecules and charge impurities in SiO2 (ref. 23), but the behaviour remains strongly ambipolar (Supplementary Fig. S12b), indicating that the amount of trapped charge is not significant compared with the MoS2 floating gate. For the thick hBN barrier of 11 nm, the memory operation is also poor. As shown in Fig. 4b, although the hysteresis in p-type GFET operation can be utilized for memory operation, the on/off current ratio was smaller than that obtained using more optimized heterostacks demonstrated in Fig. 2 (GBM3). Similarly, the thicknesses of hBN and graphene in MBG devices influence the FET performance (see Supplementary Fig. S11). When the thicknesses of the tunnel barrier of hBN and charge-trapping layer of graphene are reduced, larger hysteresis and higher on/off current ratio are observed. This is because larger amount of charge can tunnel through thinner hBN and the electric field by a gate voltage is more weakly screened by thinner graphene7,13,37.

Discussion

We now discuss a potential source of the asymmetric gate characteristics with the MoS2 floating gate. The asymmetry of the observed hysteresis suggests that tunnelling of electrons and holes at positive and negative gate voltages is asymmetric. This asymmetry can be due to different tunnel barrier heights for electrons and holes13, or a larger effective mass of holes (mh=0.5 m0) than electrons (me=0.26 m0) in hBN38. A large electron tunnelling probability39 can lead to a gate-independent channel current at positive gate voltages, as shown in GBM2 and GBM3; electrons in the graphene tunnel rapidly into the MoS2 trap layer and then screen the electric field from the back gate to reach the graphene channel, whereas the low possibility of hole-tunnelling process does not provide enough charge for screening. This effect is not seen in GBM1, with monolayer MoS2 (Supplementary Fig. S4a); in such a device with very thin MoS2-trapping layers, the amount of trapped charges might not be enough to provide sufficient gate-field screening. The larger hysteresis observed in GBM3 than that in GBM2 (Supplementary Fig. S4b,c) is because of the thinner hBN tunnelling layer and thicker MoS2-trapping layer in GBM3, which induces larger electron tunnelling current providing better screening.

We now discuss the dynamic transition rate of floating gate devices. For this purpose, we pulse the gate and measure the transfer characteristics to estimate the trapping and detrapping rates of the charge into and from the charge-trapping layer. Figure 4b shows the hysteresis of device GBM2 as a function of gate pulse width. Here the gate pulses of ±80 V were applied, with the varying pulse width in the range of 1 ms–6 s followed by the transfer curve measurement. The transfer characteristics are measured as reverse sweeps (+40 to −40 V) following +80 V gate pulses, and forward sweeps (−40 to +40 V) following −80 V gate pulses. The transfer curve hysteresis loop widens with increasing pulse width up to 6 s, and saturates after that (Fig. 4b). As the saturated gate voltage shift (ΔVs) is ~17 V, charge-trap density is estimated to be N=CoxΔVs/e~1.28 × 1012 cm−2, which is larger than a typical trap-charge density of 2.5 × 1011 cm−2 in SiO2 (ref. 40). The electron trapping rate in MoS2 (or, equivalently, the hole-releasing rate from MoS2) is then estimated from (dNtrap/dt)=(Cox/e) (dVG/dt) by using dVG/dt~ΔVs/Δt, where Δt is the pulse width and ΔVs is the gate voltage shift. Figure 4c shows both ΔVs and charge-trapping rate as a function of gate pulse width. The charge-trapping rate (dNtrap/dt) varies from 1013 to 1011 cm−2 s−1 as the pulse width changes from 1 ms to 6 s, indicating the energy level of the trap sites may differ considerably. We also note that the charge-trapping rate is relatively fast compared with a typical value, ~109 cm−2 s−1, in metal–insulator–semiconductor41. Separating from the trapping rate, the charge-transfer rate, dNtransfer/dt, governed by the tunnelling process, can be estimated from the tunnelling current. In principle, the charge-transfer rate can be expressed by dNtransfer/dt=Itunnel/Ae, where Itunnel, A and e are tunnel current, device area and electric charge, respectively. Although we have not monitored the gate tunnelling current, we can utilize the tunnelling measurement result across an hBN layer of similar thickness (see Supplementary Fig. S10), where a charge-transfer rate of 1.18 × 1013 cm−2 s−1 is estimated. Note that this value is similar to the charge-trapping rate for the short period of pulse <1 ms, but larger for the longer period of pulse shown in Fig. 4c. This suggests that trapping dynamic control is more important than the tunnelling process control for fast memory operation at this point. We believe that this charge-trapping rate can be further enhanced by optimizing the thickness of hBN and MoS2 layers, so that ΔV can be enlarged to be more suitable for faster memory device application. Figure 4d shows transfer curves of MBG1 measured with various pulse widths of VG=±30 V. Both ΔVs and charge-trapping rate as a function of gate pulse width are shown in Fig. 4e. The MBG device showed the reasonable memory window even at short pulse width of 10 μs. The charge-trapping rate varies from 1014 to 109 cm−2 s−1. It should be noted that charge-trapping rate at the same pulse width is slower compared with GBM devices. As the thickness of hBN used in MBG and GBM devices here is similar, the difference in charge-trapping rate is attributed to the smaller density of states in the MBG device compared with the GBM device.

We studied the charge-trapping characteristics of MoS2 and graphene in multi-stacked graphene/hBN/MoS2 (GBM) and MoS2/hBN/graphene (MBG) devices. GBM devices on the stacked hBN/MoS2 showed different hysteresis characteristics, depending on the thicknesses of MoS2 and hBN. From the measurement of retention and endurance characteristics, it was confirmed that the MoS2 layer acts as an effective charge-trapping layer. When thicker MoS2 layer and thinner hBN were employed, unipolar conductance and larger hysteresis were observed because of effective electron tunnelling and electric-field screening. Meanwhile, when the reversed stacking structure of MBG was investigated, high on/off current ratio and large memory window were attained. This study provides a promising route of future flexible and transparent memory device operation, utilizing ultrathin and flexible 2D materials.

Methods

Device fabrication

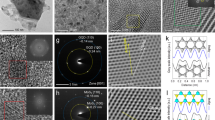

Heterostructured devices were fabricated by stacking 2D materials. For GBM devices, thin layers of MoS2 were mechanically exfoliated on a silicon wafer with 280-nm-thick SiO2. After hBN and SLG were exfoliated onto wafers coated with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and a thin release layer, PMMA film was removed from the wafer, then hBN and SLG were sequentially transferred onto the wafer containing the MoS2, as reported previously4,13 (see Supplementary Fig. S1). MBG devices were fabricated by a similar method, in a reverse-stacking order. For removal of PMMA residues generated during the stacking process, the samples were annealed at 345 °C by flowing H2/Ar-forming gas between transfer steps4,13. Source and drain electrodes were patterned using electron-beam lithography and deposition of Cr/Pd/Au (1/10/50 nm) for GBM and Ti/Au (0.5/50 nm) for MBG, where the doped Si substrate underneath the SiO2 layer was used as a back gate. To verify the effect of charge-trapping layer, two devices with or without charge-trapping layer are fabricated by an additional electron-beam lithography process followed by oxygen plasma etching.

Characterization of materials

Atomic force microscopy (Park Systems, XE-100) and Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw, inVia) were used to ensure the qualities and thicknesses of graphene, hBN and MoS2. The laser of 532 nm wavelength was used for the excitation in Raman spectroscopy. Even though Raman spectra of MoS2 covered by hBN are not sharp as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2a, the separation between two peaks indicate the number of layers. To check the quality of MoS2, hBN and graphene, therefore, the exfoliated flakes were tested using Raman spectroscopy and micro-PL spectroscopy before the transfer steps as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2b–d. It is difficult to estimate the defect density in graphene sitting on hBN, because the D peak of graphene and the main peak of hBN are located at the same position of 1,370 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S2d)42. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2a,b, MoS2 flakes with various thicknesses showed different peak separations and PL intensities as reported6,43. The narrow width (~80 meV) of PL peak around 1.84 eV indicates that MoS2 has high crystallinity6.

Electrical characterization of devices

Electrical properties of fabricated devices were measured with a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Agilent, 4155C) in vacuum and at room temperature. The fabricated GBM and MBG devices showed high mobilities of graphene (~4,200 cm2 V−1 s−1) and MoS2 (~35 cm2 V−1 s−1 for three layers). For measurement of tunnelling current through hBN, a simple metal–insulator–metal device was fabricated as shown in Supplementary Fig. S10a. To make a flat bottom electrode, a pristine few-layer graphene was used. The breakdown voltage for Fowler–Nordheim tunnelling in this device is ~6 V (6 MV cm−1), which corresponds to the electric field of 180 V when using Si back gate in a Si substrate with 300-nm-thick SiO2. This indicates that, because back gate voltage of 40 V was used in the GBM devices, the Fowler–Nordheim tunnelling does not take place in the devices. Even though the dielectric strength in this device is smaller than the reported value (8 MV cm−1; ref. 7), high-temperature treatment-like annealing process can lower the dielectric strength of hBN by generating defects44. As the annealing temperature increases, tunnelling current through hBN was enhanced probably by trap-assisted tunnelling. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S10b, tunnelling current through hBN slightly increases with temperature. However, tunnelling was not affected by exposure of light (100 W) as shown in Supplementary Fig. S10c.

Measurement of temperature dependence

To clarify the effect of temperature on tunnelling and charge trapping, transfer curves of the GBM4 and MBG3 devices were obtained at different temperature as shown in Supplementary Fig. S8. For GBM4 device, even though a small decrease in on-current, maybe due to thermal disturbance, was observed, large hysteresis was maintained at 200 °C. It is estimated that the larger memory window and two charge-neutral points at both negative- and positive-gate voltages are attributed to p-doping of graphene during the fabrication process. In contrast, the MBG3 device exhibited no significant temperature dependence as shown in Supplementary Fig. S8b. The small increase in hysteresis and on-current are probably due to thermal excitation to overcome the contact barrier between MoS2 and metal electrode. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S9, there is no appreciable difference in retention performance of the MBG3 device even at 200 °C. The trapped charge can be released by back-tunnelling, and tunnelling can be assisted by high temperature. However, our result indicates that the trapped charge can be stored efficiently without any loss. Therefore, it is evident that the heterostructure memory devices suggested in this study are stable at high temperature; therefore, it can be applied in the harsh conditions.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Choi, M. S. et al. Controlled charge trapping by molybdenum disulphide and graphene in ultrathin heterostructured memory devices. Nat. Commun. 4:1624 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2652 (2013).

References

Bae, S. et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 574–578 (2010) .

Schwierz, F. . Graphene transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 487–496 (2010) .

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004) .

Dean, C. R. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 722–726 (2010) .

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. . Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011) .

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. . Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010) .

Lee, G. H. et al. Electron tunneling through atomically flat and ultrathin hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 243114 (2011) .

Li, X. S. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009) .

Kim, K. S. et al. Large-scale pattern growth of graphene films for stretchable transparent electrodes. Nature 457, 706–710 (2009) .

Song, L. et al. Large scale growth and characterization of atomic hexagonal boron nitride layers. Nano Lett. 10, 3209–3215 (2010) .

Lee, K. H. et al. Large-scale synthesis of high-quality hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets for large-area graphene electronics. Nano Lett. 12, 714–718 (2012) .

Zhan, Y., Liu, Z., Najmaei, S., Ajayan, P. M. & Lou, J. . Large-area vapor-phase growth and characterization of MoS2 atomic layers on a SiO2 substrate. Small 8, 966–971 (2012) .

Britnell, L. et al. Field-effect tunneling transistor based on vertical graphene heterostructures. Science 335, 947–950 (2012) .

Castro Neto, A. H. & Novoselov, K. . New directions in science and technology: two-dimensional crystals. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 082501–082509 (2011) .

Novoselov, K. S. & Castro Neto, A. H. . Two-dimensional crystals-based heterostructures: materials with tailored properties. Phys. Script. T146, 014006 (2012) .

Hong, S. K., Kim, J. E., Kim, S. O., Choi, S. Y. & Cho, B. J. . Flexible resistive switching memory device based on graphene oxide. IEEE Electr. Device. Lett. 31, 1005–1007 (2010) .

Stutzel, E. U. et al. A graphene nanoribbon memory cell. Small 6, 2822–2825 (2010) .

Zhan, N., Olmedo, M., Wang, G. P. & Liu, J. L. . Graphene based nickel nanocrystal flash memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 113112 (2011) .

Park, J. K., Song, S. M., Mun, J. H. & Cho, B. J. . Graphene gate electrode for MOS structure-based electronic devices. Nano Lett. 11, 5383–5386 (2011) .

Hong, A. J. et al. Graphene flash memory. ACS Nano 5, 7812–7817 (2011) .

Cui, P. et al. Nonvolatile memory device using gold nanoparticles covalently bound to reduced graphene oxide. Acs Nano 5, 6826–6833 (2011) .

Doh, Y. J. & Yi, G. C. . Nonvolatile memory devices based on few-layer graphene films. Nanotechnology 21, 105204 (2010) .

Wang, H. M., Wu, Y. H., Cong, C. X., Shang, J. Z. & Yu, T. . Hysteresis of electronic transport in graphene transistors. Acs Nano 4, 7221–7228 (2010) .

Lee, Y. G. et al. Fast transient charging at the graphene/SiO2 interface causing hysteretic device characteristics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 183508 (2011) .

Bertolazzi, S., Brivio, J. & Kis, A. . Stretching and breaking of ultrathin MoS2. Acs Nano 5, 9703–9709 (2011) .

Mayorov, A. S. et al. Micrometer-scale ballistic transport in encapsulated graphene at room temperature. Nano Lett. 11, 2396–2399 (2011) .

Brown, W. D. & Brewer, J. . Nonvolatile Semiconductor Memory Technology: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and to Using NVSM Devices IEEE Press (1998) .

Yang, H. et al. Graphene barristor, a triode device with a gate-controlled Schottky barrier. Science 336, 1140–1143 (2012) .

Sekitani, T. et al. Organic nonvolatile memory transistors for flexible sensor arrays. Science 326, 1516–1519 (2009) .

Kim, S. J. & Lee, J. S. . Flexible organic transistor memory devices. Nano Lett. 10, 2884–2890 (2010) .

Schlaf, R., Lang, O., Pettenkofer, C. & Jaegermann, W. . Band lineup of layered semiconductor heterointerfaces prepared by van der Waals epitaxy: Charge transfer correction term for the electron affinity rule. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 2732–2753 (1999) .

Hughes, H. P. & Starnberg, H. I. . Electron Spectroscopies Applied to Low-Dimensional Structures Kluwer Academic Publishers (2000) .

Cumings, J. & Zettl, A. . Field emission and current-voltage properties of boron nitride nanotubes. Solid State Commun. 129, 661–664 (2004) .

Yu, Y. J. et al. Tuning the graphene work function by electric field effect. Nano Lett. 9, 3430–3434 (2009) .

Li, H., Zhang, Q., Liu, C., Xu, S. H. & Gao, P. Q. . Ambipolar to unipolar conversion in graphene field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 5, 3198–3203 (2011) .

Imam, S. A. et al. Charge transfer hysteresis in graphene dual-dielectric memory cell structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 082109 (2011) .

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. . The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009) .

Xu, Y. N. & Ching, W. Y. . Calculation of ground-state and optical-properties of boron nitrides in the hexagonal, cubic, and Wurtzite structures. Phys. Rev. B 44, 7787–7798 (1991) .

Oneill, A. G. . An explanation of the asymmetry in electron and hole tunnel currents through ultra-thin Sio2-films. Solid State Electron 29, 305–310 (1986) .

Watanabe, K. . Dependence of effective carrier lifetime in iron-doped silicon crystals on the carrier injection level. Semicond. Sci. Tech. 11, 1713–1717 (1996) .

Kong, Y. C. et al. Charge storage characteristics in Al/AIN/Si metal-insulator-semiconductor structure based on deep traps in AIN layer. Appl. Phys. A 90, 545–548 (2008) .

Liu, Z. et al. Direct growth of graphene/hexagonal boron nitride stacked layers. Nano Lett. 11, 2032–2037 (2011) .

Lee, C. et al. Anomalous lattice vibrations of single- and few-layer MoS2 . ACS Nano 4, 2695–2700 (2010) .

Gupta, A. et al. Accurate determination of ultrathin gate oxide thickness and effective polysilicon doping of CMOS devices. IEEE Electron Dev. Lett. 18, 580–582 (1997) .

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0083540, 2011-0010274), and by the U.S. National Science Foundation (DMR-1122594).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.C., G.H.L. and Y.J.Y. designed the research project and supervised the experiment. M.S.C., G.H.L. and Y.J.Y. performed device fabrication under the supervision of J.H. and P.K. G.H.L. performed optical spectroscopy and data analysis. M.S.C., D.Y.L. and S.H.L. performed measurements of devices under the supervision of W.J.Y.’s supervision. M.S.C., G.H.L., and W.J.Y. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S12 and Supplementary Tables S1-S2 (PDF 1124 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sup Choi, M., Lee, GH., Yu, YJ. et al. Controlled charge trapping by molybdenum disulphide and graphene in ultrathin heterostructured memory devices. Nat Commun 4, 1624 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2652

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2652

This article is cited by

-

Simultaneously ultrafast and robust two-dimensional flash memory devices based on phase-engineered edge contacts

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Wide-range and area-selective threshold voltage tunability in ultrathin indium oxide transistors

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Artificial visual perception neural system using a solution-processable MoS2-based in-memory light sensor

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

-

2D materials: increscent quantum flatland with immense potential for applications

Nano Convergence (2022)

-

Low-voltage ultrafast nonvolatile memory via direct charge injection through a threshold resistive-switching layer

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.