Abstract

The integration of organic semiconductors and magnetism has been a fascinating topic for fundamental scientific research and future applications in electronics, because organic semiconductors are expected to possess a large spin-dependent transport length based on weak spin–orbit coupling and weak hyperfine interaction. However, to date, this length has typically been limited to several nanometres at room temperature, and a large length has only been observed at low temperatures. Here we report on a novel organic spin valve device using C60 as the spacer layer. A magnetoresistance ratio of over 5% was observed at room temperature, which is one of the highest magnetoresistance ratios ever reported. Most importantly, a large spin-dependent transport length of approximately 110 nm was experimentally observed for the C60 layer at room temperature. These results provide insights for further understanding spin transport in organic semiconductors and may strongly advance the development of spin-based organic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The manipulation and utilization of the spin polarization of electrons in organic semiconductors (OSs) has attracted considerable research interest for fundamental material science and potential applications. OSs are expected to possess a large spin-dependent transport (SDT) length due to their weak spin–orbit coupling and weak hyperfine interaction1,2,3,4,5,6. The SDT phenomenon at room temperature via a tunnelling mechanism has been studied in several different OSs7,8,9,10,11,12. Nevertheless, the thickness of the OS layer is generally limited to around several nanometres, as the magnetoresistance (MR) ratio decays sharply, and subsequently disappears with increasing OS thickness. The observation of SDT in OSs in the hopping process has also been reported2,3 in such materials as tris(8-hydroxyquinolinato) aluminium (Alq3) and rubrene. However, most studies have only been carried out at low temperatures because of the evident reduction in the SDT length with increasing measurement temperatures until the MR effect finally disappears at room temperature2,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Thus, whether a large SDT length can be realized in OSs at room temperature remains unclear.

The traditional optical pump–probe method used for studying spin dynamics and transport in inorganic semiconductors is not suitable for OSs because of the weak spin–orbit interaction and the absence of a crystalline structure with inversion asymmetry in OSs16,17. The use of an organic spin valve device is still the most popular technique for investigating SDT in OSs2. An organic spin valve is a multilayer device composed of two ferromagnetic (FM) electrodes separated by an OS spacer layer. The spin valve exhibits the MR phenomenon, that is, the change in electrical resistance depends on the magnetization alignment of the two FM electrodes. Thus, the device can be used to directly investigate the SDT properties of OSs by measuring the MR effect.

Here we report on a novel organic spin valve device with an MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O/C60/Co/Al stacking structure; we studied spin injection, transport and detection in the device. An MR ratio greater than 5% was observed at room temperature, which is one of the highest MR ratios reported to date7,8,10,11,12,13. Most importantly, a large SDT length of approximately 110 nm was experimentally observed in the C60 layer at room temperature. This research may strongly motivate the development of spin-based organic devices, such as organic spin valves1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 and spin-based organic light-emitting diodes20.

Results

Device structure

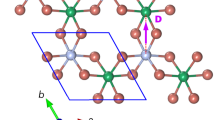

Here we report on a functional organic spin valve device with an MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O/C60/Co/Al stacking structure. A schematic diagram of the spin valve structure that was investigated is shown in Fig. 1a. Fe3O4 was selected as the bottom FM electrode, because density-functional calculations show that the electrons of Fe3O4 at the Fermi level are 100% spin-polarized21,22, which is suitable for efficient spin injection even though the actual spin polarization of Fe3O4 is affected by the contact interface23,24,25,26,27. The Verwey transition temperature was observed to be 117 K for a Fe3O4 film (Supplementary Fig. S1), confirming the high quality of the film. A stable Al-O layer was used to protect the surface of the Fe3O4 layer for mask exchange and increased spin injection efficiency. A C60 molecule was used as the organic layer, and Co was used as the top FM electrode. C60 is stable and easily forms a high-quality molecular film via thermal evaporation. In particular, the hyperfine interaction in C60 is considerably weak because of the absence of polarized hydrogen nuclei and the low natural abundance of 13C nuclear spins in the C60 molecule11,12,14,15. The weak hyperfine interaction has been predicted to increase the SDT length 28, which has been demonstrated at low temperatures using a deuterated polymer as a spacer in organic spin valve devices29. In addition, the C60 molecule is nearly isotropic because of its high symmetry and rotational freedom. Therefore, a polarized electron can easily move from one molecule to the next with a smaller spin flip, because the energy loss of the carrier is small between hopping states30 compared with other strongly anisotropic OSs, such as Alq3. These characteristics of C60 can potentially increase the SDT length in spin-based organic devices. Furthermore, the energy levels of Fe3O4, C60 and Co are well matched, as shown in Fig. 1b. Thus, in principle, electron spin injection, transport and detection can be realized in the present organic spin valve device.

(a) Schematic diagram of the device structure with an MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O/C60/Co/Al stacking structure. (b) Schematic band diagram of the organic device in the rigid band approximation shows the Fermi levels (EF), the work functions of the two ferromagnetic electrodes (Fe3O4 and Co), the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels of C60.

Hysteresis curves and spin transport properties

Figure 2a shows the hysteresis curves for the individual electrodes of Fe3O4 and Co, which were measured at 300 K. Coercivities near 140 and 40 Oe for Fe3O4 and Co, respectively, can be clearly observed. The different coercivities induce magnetization alignments with antiparallel and parallel alignments in the organic spin-valve devices (Supplementary Fig. S2), providing a precondition for investigating the MR effect. The MR curves for the device with an 80-nm-thick C60 layer measured at 300, 250, 200 and 150 K are shown in Fig. 2b. As expected, at 300 K, MR peaks appeared at around ±100 Oe, in good agreement with the observations in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S2. The MR gradually decreased on either side towards the large-field value (Fig. 2b). In spin-valve devices, the shape of the MR curve depends on the angle θ between the magnetization moments of two FM electrodes31,32,33. If the hysteresis curves of both electrodes have ideally rectangular shapes, θ can take only two values, 0° and 180°. In general, a smaller and larger MR appear when the magnetization alignment is parallel (θ is 0°) and antiparallel (θ is 180°), respectively. In contrast, if the hysteresis curves of electrodes are not ideally rectangular, particularly for Fe3O4, θ will take other values (0°<θ<180°), as shown in Fig. 2a. In this case, the MR is continuously reduced with decreasing θ until θ equals 0° (Fig. 2b).

(a) Hysteresis curves for individual electrodes Fe3O4 (black curve) and Co (red curve), which were measured at 300 K. (b) Magnetoresistance curves of the organic device composed of a 80-nm-thick C60 layer measured at different temperatures, showing magnetoresistance ratios of 5.3% at 300 K (black curve), 6.1% at 250 K (red curve), 6.7% at 200 K (blue curve) and 6.9% at 150 K (dark cyan curve). The bias voltage was fixed at 30 mV to measure the magnetoresistance effect. (c) Bias-voltage dependence of ΔR/Rp at 300 K (red circles) and 150 K (black circles) for a device with of a 80-nm-thick C60 layer. (d) Nonlinear current–voltage curves for the device with a 80-nm-thick C60 layer at 300 K (black curve), 250 K (red curve), 200 K (blue curve) and 150 K (dark cyan curve). (e) Conductance versus bias curves for a device with a 10-nm-thick C60 layer measured at 300 K (red squares) and 150 K (black squares), and the corresponding nonlinear current–voltage curve (blue circles) at 300 K.

The MR ratio was calculated using the expression ΔR/Rp=(Rap/Rp−1) × 100%, where Rap and Rp denote the resistance in the antiparallel and parallel states, respectively. The Rp value was obtained at a magnetic field of 3,000 Oe. The calculation shows an MR ratio of 5.3% at 300 K, which is one of the highest MR ratios that have been reported at room temperature7,8,10,11,12,13. Note that both the MR ratios and device resistance increased with decreasing measurement temperatures. The MR ratios were 6.1% at 250 K, 6.7% at 200 K and 6.9% at 150 K. The bias-voltage dependence of the MR ratio at 300 and 150 K is shown in Fig. 2c. The clearly nonlinear nature of the current–voltage curves can be observed in Fig. 2d. Similar conductance-bias curves were observed at 300 and 150 K for the device with a 10-nm-thick C60 layer, as shown in Fig. 2e. The primary difference was the downshift of the curve at 150 K due to the increase in the resistance, indicating that the C60 layer may have been free of magnetic inclusions7. A detailed analysis about the nonlinear behaviors of current-voltage curves in Fig. 2d and 2e can be found in the Supplementary Discussion.

Microstructure of an organic device

To further explore the microstructure of the organic spin-valve devices, scanning transmission electron microscopy and elementary mapping by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy were performed for an organic spin-valve device. The microscopy images of Fig. 3a show that each layer had a sharp interface and that the C60 layer was homogeneous. The elementary mappings of C, Co and Al showed a clear separation for each layer, as shown in Fig. 3b–d, respectively. These studies further demonstrate that there was no appreciable diffusion of Co into the C60 layer. Thus, it is very likely that the ‘ill-defined’ layer due to metal inclusions that is assumed for the organic layer in Alq3-based spin valve devices2 does not appear in our devices. One possible reason for the absence of this layer is the difference between the spatial structures of the C60 and Alq3 molecules (Supplementary Fig. S3). The spherical structure of C60 makes the sustenance of the upper metallic layer easy. The ‘ill-defined’ layer may also be related to the fabrication methods7,8,10,29. The Raman spectrum for the C60 layer was measured for an organic spin valve device (Supplementary Fig. S4), confirming the typical molecular characteristics of C60.

(a) Scanning transmission electron microscopy of a device with an MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O/C60/Co/Al stacking structure; the top C layer was deposited to protect the device layers during microscopy measurements. Scale bar, 100 nm. Panels b–d are the elementary mappings of C (red), Co (cyan) and Al (yellow), respectively, for K-shell electrons performed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

Demonstration of MR effect originates from spin valve device

The MR effect could also arise from the anisotropic MR effects of the FM electrodes themselves. Therefore, the anisotropic MR ratios for the full length of the Fe3O4 and Co strips were evaluated. The anisotropic MR ratios were found to be approximately −0.04 and 0.12% for the Fe3O4 and Co layers, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S5). These values were 40 times lower than the MR ratios of the organic spin valve devices, which demonstrates that the observed MR ratio was not due to the anisotropic MR effect. Meanwhile, a spin valve-like MR phenomenon, known as tunnelling anisotropic MR34, was examined by fabricating the devices with an MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O/C60/Al stacking structure. There were no tunnelling anisotropic MR effects in these devices (Supplementary Fig. S6). On the basis of this systemic investigation, the MR effect in our organic spin valve devices could conclusively be attributed to the SDT of the C60 layer.

Dependence of MR ratio on C60 thickness

A set of organic spin valve devices consisting of different C60 layer thicknesses (10–110 nm) were fabricated. The measured MR curves were similar to that shown in Fig. 2b for all devices (Supplementary Fig. S7 shows one such curve). The dependence of the MR ratio on the C60 layer thickness at 300 and 150 K is plotted in Fig. 4a. The MR ratios at 150 K were larger than those at 300 K for each corresponding C60 layer thickness due to the decrease in spin scattering (such as magneto-excitation) at lower temperatures. Notably, an unusual and interesting dependence of the MR ratio on the C60 layer thickness was observed, which differs from previous reports. The MR ratios sharply increased upon increasing the C60 layer thickness from 10 to 40 nm and then slowly increased for increases in the C60 layer up to 80 nm. Beyond this range, further increases in the C60 layer thickness produced a drastic reduction in the MR ratio. Fortunately, a C60 layer thickness of 110 nm was successfully observed with an MR ratio of approximately 0.5% at room temperature in the devices. To the best of our knowledge, this thickness is the largest SDT length reported at room temperature in OSs with vertical spin valve structures to date. We suggest that when compared with other reported OSs, such as rubrene and Alq3, the weaker spin–orbit coupling and hyperfine interaction of the C60 molecule14,28,29 significantly reduces spin flip in the organic film. Thus, a large SDT length was obtained for the C60 layer. Our results indicate that the SDT length relies strongly on the molecular configuration of the OS.

(a) ΔR/Rp as a function of the C60 layer thickness measured at 300 K (black circles) and 150 K (red circles). The bias voltage was fixed at 30 mV to measure magnetoresistance effect. Error bar represent one standard deviation of ΔR/Rp for every thickness and is estimated based on the scatter in the date of ΔR/Rp from four devices at each thickness. (b) Activation energy (black squares) and electric field magnitude (red circles) as a function of the C60 layer thickness. (c) Dependence of the roughness (black squares) and growth rate (blue triangles) on the evaporation temperature for the 80-nm-thick C60 films; the solid curves in b and c are only visual guides.

To analyse the dependence of the MR ratio on the C60 layer thickness, the structures of the C60 layers were studied. X-ray diffraction measurements showed that the C60 layers of different thickness were structurally amorphous. The C60 layer thickness in our devices was far greater than the tunnelling barrier limit that has been reported thus far7,8,9,10,11,12,35. Thus, the SDT within the C60 layer via hopping between localized neighbouring states was mainly considered. Our results can therefore be described by the Gaussian disorder model. Bobbert et al.28 presented a theory for spin transport in disordered OSs. The authors concluded that both the spin diffusion length (ls) and mobility (μ) decreased with a decreasing electric field (E) (E<5[σ/ea]). E was determined by the equation E=U/d, where U and d are the applied voltage and distance between two electrodes, respectively. In our spin valve devices, U was fixed at 30 mV and d was determined by the C60 layer thickness. Thus, as the C60 layer thickness increased, E decreased, as shown in Fig. 4b. As a result, ls and μ decreased. Bobbert et al.28 also suggested that ls and μ increase with decreasing disorder strength. The activation energy (Ea) is a direct reflection of the amount of disorder strength36. The Ea of C60 was estimated from the temperature dependence of the resistance (Supplementary Fig. S8) and is plotted in Fig. 4b. Ea clearly decreased with increasing C60 thickness, indicating that the disorder strength of the C60 layer decreased. This result indicates that ls and μ increased with increasing C60 thickness. The competition between these two factors (E and disorder) likely leads to a maximum for both ls and μ. As ls and μ increase, the dependence of MR on the magnetization alignments of the two electrodes becomes stronger, which is the origin of the MR effect28. Consequently, a maximum of ΔR/Rp can appear with increasing C60 layer thickness. The change ratios for ls and μ were distinctly different for different values of E (ref.28). This observation could explain the different increasing slopes of ΔR/Rp for C60 layer thicknesses of 10–40 nm and 40–80 nm. The decrease in Ea implies that the molecular interactions between C60 molecules may vary. In our organic spin valve devices, Ea was smaller than the values reported in the literature37, likely because of the dependence of the mobility on the charge-carrier density induced by different devices36,37.

Discussion

To estimate ls in the organic spin valve devices, the MR signals were tentatively fitted by the following formula28,29, MR(B)=0.5 × MRmax[1−m1(B1) × m2(B2)]exp(−d/ls), where MRmax is the MR when spin relaxation is neglected, d is the thickness of the organic spacer, m1(B1) and m2(B2) denote the normalized magnetizations of the FM electrodes, ls=ls,0 × [1+(B/B0)2]3/8, B is the applied magnetic field and B0 is a characteristic field related to hyperfine interaction. One fit for a device with d=80 nm at 300 K and 30 mV is shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. It produces that ls,0/d is ~1.7 and MRmax is ~9%. The maximum MR ratio appears for B at ±100 Oe. Thus, the fit predicts that the largest ls value is approximately 150 nm at room temperature in our devices. On the basis of the fit values for MRmax and ls, the MR was calculated using MR=MRmax × exp(−d/ls). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S10, the dependence of the calculated MR ratio on the C60 layer thickness basically agrees with our experiments. It should be pointed out that these estimated values likely include a fitting error, because the fitting is not very exact (Supplementary Fig. S9). The above fitting formula results from the random hyperfine coupling and Zeeman coupling28. Thus, one possible reason for the presence of fitting error is that other interactions, such as the exchange interaction or/and spin–orbit coupling, also contribute to the spin transport in OSs, as was suggested in 29 and studied in 38. Further studies are needed to clarify the effect of these other interactions on spin transport in detail.

The interfaces between the FM electrodes and molecular layer determine the spin injection and detection efficiency, and thus significantly affect the MR ratio of organic spin valve devices. Spin valve devices with an MgO substrate/Fe3O4/C60/Co/Al stacking structure (without an Al-O layer) were fabricated. However, the MR effect did not appear in these devices (Supplementary Fig. S11), likely because of the decrease in the spin polarization of Fe3O4 resulting from surface degradation (Supplementary Fig. S12). The thin Al-O film is very stable in air and has been known as an efficient barrier33,39. Inserting an Al-O layer to protect the Fe3O4 produced the MR effect in our spin valve devices. With the same device size, the spin valve with an Al-O layer but lacking a C60 layer also did not show an MR effect originating from the device (Supplementary Fig. S5).

The evaporation temperature of the C60 layers was 723 K for the organic spin valve devices reported above. We found that the evaporation temperature of the C60 layer had an essential role in modifying the SDT properties. Organic spin valve devices with an 80-nm-thick C60 layer were also fabricated by evaporating C60 at 673 and 773 K. Both series of devices showed MR ratios of approximately 1.7% at room temperature. These MR ratios were three times smaller than that of the device with C60 evaporated at 723 K. Note that the Rp of the devices with C60 evaporated at 673 K was approximately 12.5 kΩ, which was approximately two times smaller than that of the devices with C60 evaporated at 723 K. In contrast, the Rp of the device with C60 evaporated at 773 K was nearly 1 MΩ. The resistance was inversely proportional to the carrier mobility. The decrease of Rp at 673 K did not lead to an increase in the MR ratio, indicating that the MR ratio was not solely affected by the carrier mobility, in agreement with the analysis for Fig. 4a, as well as the literature38.

The roughness and growth rates of the C60 films for different evaporation temperatures are plotted in Fig. 4c. The roughness for all films was approximately 0.5 nm, which is less than the diameter of a C60 molecule (approximately 1 nm), indicating that the films were extremely smooth. However, the growth rates were significantly different, corresponding to 0.015, 0.045 and 0.22 nm s−1 for the films evaporated at 673, 723 and 773 K, respectively. These differences can be attributed to the different kinetic energies for the C60 molecules obtained at each evaporation temperature. The kinetic energy of the molecules clearly affected the thermal equilibrium of the individual C60 molecules when the final film formed. Thus, the molecular distance and intermolecular interactions in organic films will vary for different temperatures. The intermolecular distance and interactions may affect the orbital overlap of the π electrons in OSs40, which determine the transport efficiency of the charge carriers. Previous studies have also reported that temperature affects the lattice fluctuations41,42 and intramolecular interactions30,43 of C60, which may cause variations in the σ-orbital. The σ-orbital affects the SDT length in organic OSs38. Moreover, the C60 molecule exhibits a series of energy levels41. The evaporation temperature may affect the distribution of the energy levels in a C60 layer. This energy redistribution can reduce the matching of energy levels between the C60 molecules for hopping transport, thus decreasing the hopping efficiency of the C60 layer. Meanwhile, the energy redistribution may also change the interactions between the C60 energy levels and electrodes at the interfaces, leading to lower spin injection and/or detection efficiencies. This study has shown that the microstructure in organic spin valve devices is closely correlated with magnetotransport, in agreement with the literature44. On the basis of an optimized evaporation temperature for the C60 layer at 723 K, we deduced that an efficient SDT pathway exists in a spin valve device with a C60 layer of 80 nm for achieving a high MR ratio in which spin electrons are efficiently injected17,45 into the C60 layer and hopping transport occurs with very a small spin flip, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The most recent theoretical investigation predicts that an SDT length of more than 430 nm for C60 can be achieved at room temperature46. Our results are consistent with this theoretical study. In the organic spin valve devices considered here, the C60 layer had an amorphous structure. Thus, a larger SDT length for C60 layers at room temperature can be expected when C60 forms a single crystalline structure.

In conclusion, we have shown that a large SDT length of approximately 110 nm for C60 can be realized in room-temperature experiments. The large SDT length is likely governed by the weak hyperfine interactions of the C60 molecule. The spin injection/detection efficiency at the interface of the electrode/molecule together with the molecular interactions determines the value of the MR ratio. Such an investigation furthers our understanding of spin transport in OSs and could be pivotal in the development of spin-based molecular electronics for future applications.

Methods

Sample fabrication

The Fe3O4 (70 nm) electrode was deposited using ultrahigh-vacuum magnetron sputtering (at a base pressure of 10−9 Torr) with a shadow mask to form a strip on an MgO (001) substrate. Al (2 nm) was deposited on the MgO substrate/Fe3O4 layer in the same chamber, followed by immediate oxidization by exposure to oxygen plasma to obtain an Al-O layer. The MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O film was removed from the chamber, and then the mask was removed in air. The film was then installed into the thermal evaporation chamber (base pressure <10−6 Torr) for molecular deposition. A new shadow mask was used to form a rotund C60 layer (99.9%, Strem Chemicals Inc.). The MgO substrate/Fe3O4/Al-O/C60 layers were transferred to a different chamber, without breaking the vacuum, to deposit a Co layer (10 nm) via magnetron sputtering (base pressure <10−7 Torr; Ar ion plasma). A third shadow mask was inserted to form a Co strip for patterning a cross configuration. Finally, Al (5 nm) was deposited to prevent oxidation of the Co layer. The top Co/Al layer was deposited at a very low electric power (10 W) to reduce the kinetic energy of the Co and Al atoms. The substrate was rotated using a mechanical motor during the deposition for each layer to homogenize the film. The fabricated device area was 1.5 × 1.5 mm2.

Experimental setup

Transport properties were measured via the standard four-probe method using a physical property measurement system (Quantum Design). The crystal structures for the thin films were characterized using X-ray diffraction (Smartlab, Rigaku Co.). The magnetization curves were measured using a vibrating-sample magnetometer with an applied field parallel to the film plane. The film roughness was characterized by atomic force microscopy (SII Seiko Instruments, SPA 400). Scanning transmission electron microscopy was performed using a HD-2700 (Hitachi Co.) with the acceleration voltage set at 200 kV. Elementary mapping was performed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (HD-2700) with the accelerating voltage set at 200 kV and an Si/Li detector. Raman spectroscopy was performed using a LabRAM HR 800 Raman Spectrometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon Co.) with the Ar+ laser wavelength set at 514.5 nm.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhang, X. et al. Observation of a large spin-dependent transport length in organic spin valves at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 4:1392 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2423 (2013).

References

Dediu, V., Murgia, M., Matacotta, F. C., Taliani, C. & Barbanera, S. . Room temperature spin polarized injection in organic semiconductors. Solid State Commun. 122, 181–184 (2002) .

Xiong, Z. H., Wu, D., Vardeny, Z. V. & Shi, J. . Giant magnetoresistance in organic spin valves. Nature 427, 821–824 (2004) .

Dediu, V., Hueso, L. E., Bergenti, I. & Taliani, C. . Spin routes in organic semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 8, 707–716 (2009) .

Tsukagoshi, K., Alphenaar, B. W. & Ago, H. . Coherent transport of electron spin in a ferromagnetically contacted carbon nanotube. Nature 401, 572–574 (1999) .

Hueso, L. E. et al. Transformation of spin information into large electrical signals using carbon nanotubes. Nature 445, 410–413 (2007) .

Majumdar, S. et al. Application of regioregular polythiophene in spintronic devices: effect of interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 122114 (2006) .

Santos, T. S. et al. Room-temperature tunnel magnetoresistance and spin-polarized tunneling through an organic semiconductor barrier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 016601 (2007) .

Szulczewski, G., Tokuc, H., Oguz, K. & Coey, J. M. D. . Magnetoresistance in magnetic tunnel junctions with an organic barrier and a MgO spin filter. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 202506 (2009) .

Dediu, V. et al. Room temperature spintronics effects in Alq3-based hybrid devices. Phys. Rev. B 78, 115203 (2008) .

Schoonus, J. J. et al. Magnetoresistance in hybrid organic spin valves at the onset of multiple-step tunneling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 146601 (2009) .

Gobbi, M., Golmar, F., Llopis, R., Casanova, F. & Hueso, L. E. . Room-temperature spin transport in C60 -based spin valves. Adv. Mater. 23, 1609–1613 (2011) .

Lan Anh Tran, T., Quyen Le, T., Sanderink, J. G. M., van der Wiel, W. G. & de Jong, M. P. . The multistep tunneling analogue of conductivity mismatching organic spin valves. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 1180–1189 (2012) .

Shim, J. H. et al. Large spin diffusion length in an amorphous organic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 226603 (2008) .

Nguyen, T. D. et al. The hyperfine interaction role in the spin response of π-conjugated polymer films and spin valve devices. Synthet. Metal. 161, 598–603 (2011) .

Lin, R. et al. Organic spin valves based on fullerene C60 . Synthet. Metal. 161, 553–557 (2011) .

Drew, A. J. et al. Direct measurement of the electronic spin diffusion length in a fully functional organic spin valve by low-energy muon spin rotation. Nat. Mater. 8, 109–114 (2009) .

Cinchetti, M. et al. Determination of spin injection and transport in a ferromagnet/organic semiconductor heterojunction by two-photon photoemission. Nat. Mater. 8, 115–119 (2009) .

Schulz, L. et al. Engineering spin propagation across a hybrid organic/inorganic interface using a polar layer. Nat. Mater. 10, 39–44 (2011) .

Sun, D. et al. Giant magnetoresistance in organic spin valves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 236602 (2010) .

Davis, A. H. & Bussmann, K. . Organic luminescent devices and magnetoelectronics. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 7358–7360 (2003) .

Yanase, A. & Siratori, K. . Band structure in the high temperature phase of Fe3O4 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 53, 312–317 (1984) .

Zhang, Z. & Satpathy, S. . Electron states, magnetism, and the Verwey transition in magnetite. Phys. Rev. B 44, 13319–13331 (1991) .

Fonin, M. et al. Surface electronic structure of Fe3O4 (100): evidence of a half-metal to metal transition. Phys. Rev. B 72, 104436 (2005) .

Li, X. W., Gupta, A., Xiao, G., Qian, W. & Dravid, V. P. . Fabrication and properties of heteroepitaxial magnetite (Fe3O4) tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 3282 (1998) .

Seneor, P., Fert, A., Maurice, J.-L., Montaigne, F., Petroff, F. & Vaurès, A. . Large magnetoresistance in tunnel junctions with an iron oxide electrode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 4017 (1999) .

Dedkov, S., Rüdiger, U. & Güntherodt, G. . Evidence for the half-metallic ferromagnetic state of Fe3O4 by spin-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 65, 064417 (2002) .

Hu, G. & Suzuki, Y. . Negative spin polarization of Fe3O4 in magnetite/manganite-based junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 276601 (2002) .

Bobbert, P. A., Wagemans, W., van Oost, F. W. A., Koopmans, B. & Wohlgenannt, M. . Theory for spin diffusion in disordered organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 156604 (2009) .

Nguyen, T. D. G. et al. Isotope effect in spin response of π-conjugated polymer films and devices. Nat. Mater. 9, 345–352 (2010) .

Kwiatkowski, J. J., Frost, J. M. & Nelson, J. . The effect of morphology on electron field-effect mobility in disordered C60 thin films. Nano Lett. 9, 1085–1090 (2009) .

Julliere, M. . Tunneling between ferromagnetic films. Phys. Lett. A 54, 225–226 (1975) .

Slonczewski, J. C. . Conductance and exchange coupling of two ferromagnets separated by a tunneling barrier. Phys. Rev. B 39, 6995–7002 (1989) .

Miyazaki, T. & Tezuka, N. . Giant magnetic tunneling effect in Fe/Al2O3/Fe junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 139, L231–L234 (1995) .

Gould, C. et al. Tunneling anisotropic magnetoresistance: a spin valve-like tunnel magnetoresistance using a single magnetic layer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 117203 (2004) .

Lin, R., Wang, F., Rybicki, J. & Wohlgenannt, M. . Distinguishing between tunneling and injection regimes of ferromagnet/organic semiconductor/ferromagnet junctions. Phys. Rev. B 81, 195214 (2010) .

Tanase, C., Meijer, E. J., Blom, P. W. M. & de Leeuw, D. M. . Unification of the hole transport in polymeric field-effect transistors and light-emitting diodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 216601 (2003) .

Pivrikas, A., Ullah, M., Sitter, H. & Sariciftci, N. S. . Electric field dependent activation energy of electron transport in fullerene diodes and field effect transistors: Gill’s law. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 092114 (2011) .

Yu, Z. G. . Spin-orbit coupling, spin relaxation, and spin diffusion in organic solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 106602 (2011) .

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. . Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin film tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995) .

Chu, C.-C. et al. Self-assembly of supramolecular fullerene ribbons via hydrogen-bonding interactions and their impact on fullerene electronic interactions and charge carrier mobility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12717–12723 (2010) .

Zhang, Q.-M., Yi, J.-Y. & Bernholc, J. . Structure and dynamics of solid C60 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 2633–2636 (1991) .

Harigaya, K. & Abe, S. . Optical-absorption spectra in fullerenes C60 and C70: effects of coulomb interactions, lattice fluctuations, and anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 49, 16746–16752 (1994) .

Schulz, L. et al. Importance of intramolecular electron spin relaxation in small molecule semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085209 (2011) .

Liu, Y. et al. Correlation between microstructure and magnetotransport in organic semiconductor spin-valve structures. Phys. Rev. B 79, 075312 (2009) .

Fiederling, R. et al. Injection and detection of a spin-polarized current in a light-emitting diode. Nature 402, 787–790 (1999) .

Yu, Z. G. . Spin-orbit coupling and its effects in organic solids. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115201 (2012) .

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Junqiang Wang and Dr Jianli Kang for their scientific discussions. X.M.Z. thanks the financial support from the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) of JSPS (grant no. 24750120), and the fusion research project from WPI-AIMR. S. M. thanks the financial support from the target project of WPI-AIMR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. and X.M.Z. designed the experiments. X.M.Z. fabricated all devices, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. S.M. constructed the organic evaporation setup. X.M.Z., T.K., and Q.L.M. performed the film growth and characterization experiments. M.O. and Y.A. optimized the conditions for the fabrication of the Fe3O4 film. X.M.Z. and H.N. performed the atomic force microscopy measurements. T.M. supervised the entire study. All authors participated in discussions on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S12, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 437 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Mizukami, S., Kubota, T. et al. Observation of a large spin-dependent transport length in organic spin valves at room temperature. Nat Commun 4, 1392 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2423

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2423

This article is cited by

-

Depth Resolved Magnetic Studies of Fe/57Fe/C60 Bilayer Structure Under X-Ray Standing Wave Condition

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2024)

-

Molecular design for enhanced spin transport in molecular semiconductors

Nano Research (2023)

-

Cornerstone of molecular spintronics: Strategies for reliable organic spin valves

Nano Research (2021)

-

Study of obliquely deposited 57Fe layer on organic semiconductor (Alq3); interface resolved magnetism under x-ray standing wave

Hyperfine Interactions (2021)

-

Research progress of rubrene as an excellent multifunctional organic semiconductor

Frontiers of Physics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.