Abstract

Quantum-confined devices that manipulate single electrons in graphene are emerging as attractive candidates for nanoelectronics applications. Previous experiments have employed etched graphene nanostructures, but edge and substrate disorder severely limit device functionality. Here we present a technique that builds quantum-confined structures in suspended bilayer graphene with tunnel barriers defined by external electric fields that open a bandgap, thereby eliminating both edge and substrate disorder. We report clean quantum dot formation in two regimes: at zero magnetic field B using the energy gap induced by a perpendicular electric field and at B>0 using the quantum Hall ν=0 gap for confinement. Coulomb blockade oscillations exhibit periodicity consistent with electrostatic simulations based on local top-gate geometry, a direct demonstration of local control over the band structure of graphene. This technology integrates single electron transport with high device quality and access to vibrational modes, enabling broad applications from electromechanical sensors to quantum bits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanopatterned graphene devices, from field-effect transistors to quantum dots1,2,3, have been the subject of intensive research because of their novel electronic properties and two-dimensional (2D) structure4,5. For example, nanostructured carbon is a promising candidate for spin-based quantum computation6 because of the ability to suppress hyperfine coupling to nuclear spins, a dominant source of spin decoherence7,8,9, by using isotopically pure 12C. Graphene is a particularly attractive host for lateral quantum dots as both valley and spin indices are available to encode information, a feature absent in GaAs10,11,12. Yet graphene lacks an intrinsic bandgap5, which poses a serious challenge for the creation of such devices. Transport properties of on-substrate graphene nanostructures defined by etching2,3 are severely limited by both edge disorder and charge inhomogeneities arising from ionized impurities in gate dielectrics13,14. The absence of spin blockade in etched double dots is perhaps symptomatic of these obstacles15,16. Unzipping carbon nanotubes yields clean nanoribbon dots, but this approach cannot produce arbitrarily shaped nanostructures with tunable constrictions17. However, local bandgap engineering in bilayer graphene enables production of tunable tunnel barriers defined by local electrostatic gates18, thus providing clean electron confinement isolated from edge disorder.

Bernal stacked bilayer graphene is naturally suited for bandgap control because of its rich system of degeneracies that couple to externally applied fields. At B=0, breaking layer inversion symmetry opens an energy gap tunable up to 250 meV with an external perpendicular electric field E (refs 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25) that can be used for confinement. In devices with low disorder and at high magnetic fields, gapped states emerge from Coulomb-driven effects that break its eightfold degeneracy (spin, valley and orbital), resulting in quantum Hall plateaus at all integer multiples of e2/h for electron charge e and Planck's constant h (ref. 26). Because of the Pauli exclusion principle, Coulomb repulsions between electrons favour spontaneous spin and/or valley polarization (or combinations of those), known as quantum Hall ferromagnetism, resulting in a gap at zero carrier density that far exceeds the Zeeman splitting energy gμBB (refs 27, 28). The large exchange-enhanced energy gap of Δ=1.7 meV/T measured for the ν=0 state is ideally suited for quantum confinement29. Because valley and layer indices are identical in the lowest Landau level, one may additionally induce a tunable valley gap in the density of states by applying a perpendicular E field that breaks layer inversion symmetry30. This coupling of valley index to E-field is the key property that enables direct experimental control of the relative spin and valley gap sizes in magnetic field.

Here we demonstrate a technology that enables microscopic bandgap control in graphene for the first time. We report fully suspended quantum dots in bilayer graphene with smooth, tunable tunnel barriers defined by local electrostatic gating. Local gap control in graphene opens an avenue to explore a variety of intriguing systems, including spin qubits6, topological confinement and valleytronics31, quantum Hall edge modes in an environment well-isolated from edge disorder, gate-controlled superconductivity, and many more. Although not the sole use for this technology, quantum dots provide a good experimental platform to rigorously demonstrate local bandgap engineering due to the precise quantitative relationship between dot area and quantized charge tunnelling periodicity. Our technique, which artificially modifies the bandgap of bilayer graphene over nanometer scales, achieves clean electron confinement isolated from both edge and substrate disorder.

Results

Device fabrication

We fabricate fully suspended quantum dots with 150 to 450 nm lithographic diameters as illustrated schematically in Fig. 1a following the procedure described in the Methods. Graphene is suspended between two Cr/Au electrodes and sits below suspended local top gates (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S1). Before measurement, the devices are current annealed in vacuum to enhance quality. The high quality of our suspended flakes is evident from the full lifting of the eightfold degeneracy in the quantum Hall regime (Supplementary Fig. S2)30 and large resistances attained by opening the E-field-induced gap at B=0 and E=90 V/nm, a hundred times greater than the resistance reported for on-substrate bilayers at similar electric fields22,30. Measurements are conducted in a dilution refrigerator at an electron temperature of 110 mK, as determined from fits to Coulomb blockade oscillations.

(a) Schematic cross-section of a suspended gate-defined bilayer graphene quantum dot. The electric field and carrier density profiles are controlled with back and top-gate voltages Vb and Vt, while application of a bias Vsd across the electrodes enables transport measurements. (b) Scanning electron micrograph of quantum dot device similar to D4 (see Methods for sample labelling key). Bilayer graphene (not visible) is suspended between two electrodes below local top gates. Green and blue lines indicate cross-sectional cuts in (a) and (c), respectively. Red lines mark the estimated graphene boundaries. Scale bar, 1 μm. (c) Quantum dot formation at B=0, illustrated in a cross-sectional cut of energy versus position. EC and EV mark the edges of the conductance and valence bands. Tunnel barriers are formed by inducing a bandgap with an external E field while fixing Vt and Vb at a ratio that places the Fermi energy EF within the gap. Uncompensated back-gate voltage in the non-top-gated regions enables charge accumulation in the dot and leads.

Quantum confinement at zero magnetic field

At B=0, the electric field effect in bilayer graphene enables the production of quantum-confined structures with smooth, tunable tunnel barriers defined by local gating10, thus avoiding the disorder arising from the physical edge of the flake. Broken layer inversion symmetry opens a bandgap  , where Vt and Vb are top and back-gate voltages with coupling factors α and β, respectively, and

, where Vt and Vb are top and back-gate voltages with coupling factors α and β, respectively, and  is vacuum permittivity. Coupling to the back gate β is extracted from Landau fans in the quantum Hall regime and the relative gate coupling α/β can be determined from the Dirac peak slope in a Vt versus Vb plot of conductance at B=0. Properties of individual quantum point contacts are described in greater detail in Supplementary Figs S3 and S4, where pinch-off and behaviour consistent with conductance quantization are observed. Quantum dot formation at B=0 is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1c. To create tunnel barriers beneath the top gates, we induce a bandgap by applying a field E while fixing Vt and Vb at a ratio that maintains zero carrier density n, where n=αVt+βVb. In the non-top-gated regions, there is a finite charge accumulation due to an uncompensated back-gate voltage. For gates in a quantum dot geometry, this restricts electron transport to resonant tunnelling events through the constrictions.

is vacuum permittivity. Coupling to the back gate β is extracted from Landau fans in the quantum Hall regime and the relative gate coupling α/β can be determined from the Dirac peak slope in a Vt versus Vb plot of conductance at B=0. Properties of individual quantum point contacts are described in greater detail in Supplementary Figs S3 and S4, where pinch-off and behaviour consistent with conductance quantization are observed. Quantum dot formation at B=0 is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1c. To create tunnel barriers beneath the top gates, we induce a bandgap by applying a field E while fixing Vt and Vb at a ratio that maintains zero carrier density n, where n=αVt+βVb. In the non-top-gated regions, there is a finite charge accumulation due to an uncompensated back-gate voltage. For gates in a quantum dot geometry, this restricts electron transport to resonant tunnelling events through the constrictions.

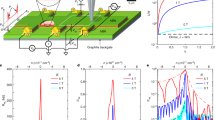

Periodic Coulomb blockade oscillations are observed at B=0 that couple to both top and back gates (Fig. 2a). A peak in the 2D Fourier transform corresponding to an oscillation spacing of ~11 mV in Vb reflects this strong periodicity (Fig. 2b), and the appearance of higher harmonics reveals the non-sinusoidal nature of the Coulomb blockade peaks when kBT EC, where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and EC is the dot-charging energy. Coulomb diamonds shown in Fig. 2c have symmetric structure that suggests equal tunnel coupling to both the source and drain leads. The dot-charging energy extracted from the DC bias data is EC~0.4 meV. Fig. 2d indicates that the periodic Coulomb blockade oscillations have comparable capacitive coupling to each pair of top gates. Furthermore, an even–odd effect is visible in a Coulomb blockade plot as a function of Vt12 at fixed Vt34=9.27 V and Vb=−10.7 V (Supplementary Fig. S5), consistent with the presence of a twofold degeneracy. The conductance modulations that couple exclusively to the back gate in Fig. 2a likely result from weak parallel conductance channels under gates 3 and 4 (as labelled in Fig. 1b) and are unrelated to the central gate-defined quantum dot formation, because capacitive coupling to Vt12 is absent. The horizontal modulations in Fig. 2d couple only to Vt34 but not Vt12 and are thus expected to have similar origins. Because these features are sparse and aperiodic in nature, we expect that they are not generated by random dot formation in the constrictions or under the local gates. We note that the highly resistive v=0 gap in the quantum Hall regime enables more robust confinement than the electric field-induced gap, and we demonstrate that all background conductance fluctuations are completely eliminated in Fig. 3.

EC, where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and EC is the dot-charging energy. Coulomb diamonds shown in Fig. 2c have symmetric structure that suggests equal tunnel coupling to both the source and drain leads. The dot-charging energy extracted from the DC bias data is EC~0.4 meV. Fig. 2d indicates that the periodic Coulomb blockade oscillations have comparable capacitive coupling to each pair of top gates. Furthermore, an even–odd effect is visible in a Coulomb blockade plot as a function of Vt12 at fixed Vt34=9.27 V and Vb=−10.7 V (Supplementary Fig. S5), consistent with the presence of a twofold degeneracy. The conductance modulations that couple exclusively to the back gate in Fig. 2a likely result from weak parallel conductance channels under gates 3 and 4 (as labelled in Fig. 1b) and are unrelated to the central gate-defined quantum dot formation, because capacitive coupling to Vt12 is absent. The horizontal modulations in Fig. 2d couple only to Vt34 but not Vt12 and are thus expected to have similar origins. Because these features are sparse and aperiodic in nature, we expect that they are not generated by random dot formation in the constrictions or under the local gates. We note that the highly resistive v=0 gap in the quantum Hall regime enables more robust confinement than the electric field-induced gap, and we demonstrate that all background conductance fluctuations are completely eliminated in Fig. 3.

(a) Conductance map (units of e2/h) of Coulomb blockade oscillations as a function of back-gate voltage (Vb) and the voltage on top gates 1 and 2 (Vt12) at T=110 mK in a four-gate dot (device D4). The voltage on top gates 3 and 4 is fixed at Vt34=9.27 V. (b) 2D fast Fourier transform (units of e2/h·V) of (a) reveals the periodic structure. A peak corresponding to an oscillation spacing of ~11 mV in Vb reflects strong periodicity, whereas the appearance of higher harmonics reveals the non-sinusoidal nature of the Coulomb blockade peaks when kB T  EC. (c) Coulomb diamonds are shown in a plot of ΔG/ΔVt12 as a function of Vt12 and VDC, where G is conductance in units of e2/h and VDC is the DC bias across the electrodes. The voltages Vb=−10.7 V and Vt34=9.27 V are held constant. Symmetric Coulomb diamonds suggests equal tunnel coupling to source and drain leads. The dot-charging energy is EC≈0.4 meV. (d) Conductance map (units of e2/h) of Coulomb blockade oscillations as a function of Vt12 and Vt34 at fixed back-gate voltage Vb=−10.7 V.

EC. (c) Coulomb diamonds are shown in a plot of ΔG/ΔVt12 as a function of Vt12 and VDC, where G is conductance in units of e2/h and VDC is the DC bias across the electrodes. The voltages Vb=−10.7 V and Vt34=9.27 V are held constant. Symmetric Coulomb diamonds suggests equal tunnel coupling to source and drain leads. The dot-charging energy is EC≈0.4 meV. (d) Conductance map (units of e2/h) of Coulomb blockade oscillations as a function of Vt12 and Vt34 at fixed back-gate voltage Vb=−10.7 V.

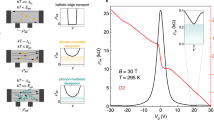

(a) Quantum dot formation at B>0, illustrated in a cross-sectional cut of energy versus position. Tunnel barriers are formed using the exchange-enhanced ν=0 gap, where high resistances due to quantum Hall ferromagnetism are ideal for confinement. An isolated puddle of charge is created by fixing the Fermi energy in the top-gated regions at the middle of the ν=0 gap while allowing occupation of higher Landau levels elsewhere. Inset: schematic illustration of the top-gate geometry for device D1. (b) Conductance map (units of e2/h) of Coulomb blockade oscillations as a function of Vt1 and Vt2 in a two top-gate dot (device D1), at fixed back-gate voltage Vb=−15.4 V and T=110 mK. The slopes of the resonances indicate symmetric coupling to the two top gates, as expected for a centrally located dot. As top-gate voltages are swept to more positive values, peak amplitude is suppressed, revealing moderate tunnel barrier tunability. Inset: scanning electron micrograph of a device similar to D1. Scale bar, 200 nm. (c) Coulomb diamonds are shown in a plot of conductance (units of e2/h) as a function of Vt1 and DC bias VDC, where Vt2=11 V and Vb=−14.4 V are fixed. Symmetric Coulomb diamonds suggests equal tunnel coupling to source and drain leads. The dot-charging energy is EC≈0.4 meV. (d) 2D fast Fourier transform (units of e2/h·V) of the boxed region in (b), revealing the strongly periodic nature of the oscillations and higher harmonics.

Coulomb blockade in the quantum Hall regime

Coulomb blockade oscillations can also be generated at finite B field using the exchange-enhanced ν=0 gap. Here the bilayer is naturally in a gapped quantum Hall state at zero density, where high resistances due to quantum Hall ferromagnetism make this system ideal for confinement. An isolated puddle of charge is created by fixing the Fermi energy in the top-gated regions at the middle of the ν=0 gap while allowing occupation of higher Landau levels elsewhere, shown schematically in Fig. 3a. It should be noted that measurements in the quantum Hall regime are conducted in the valley-polarized ν=0 state, far from the transition to the spin-polarized phase30. Figure 3b shows over 40 consecutive Coulomb blockade oscillations generated at 5.2 T in a 2-gate dot with a 400-nm lithographic diameter. The slopes of the resonances indicate symmetric coupling to the two top gates, as expected for a centrally located dot. As top-gate voltages are swept to more positive values, peak amplitude is suppressed, revealing moderate tunnel barrier tunability. Also seen in Fig. 3b are interruptions in the conductance resonances (vertical and horizontal features) that couple exclusively to a single top gate; owing to their sparse and aperiodic nature, we believe that they represent charging events below the gates. Coulomb blockade oscillations are robust over a wide voltage range: Fig. 3c shows an additional 40 peaks generated under new gate conditions. The Coulomb diamonds exhibit symmetric tunnel coupling to source and drain leads and a dot-charging energy of EC≈0.4 meV. The strongly periodic nature of the oscillations is evident in the Fourier transform of the data (Fig. 3d) (See Supplementary Fig. S6 for additional Coulomb blockade data).

Geometric control over Coulomb blockade period

To demonstrate geometric control over dot size, we examine the correspondence between top-gate dimensions and Coulomb blockade peak spacing. Measurements were performed on 5 dots with lithographic diameters ranging from 150 to 450 nm at magnetic fields of 0 to 7 T. The ability to decrease peak spacing by increasing lithographic dot size is illustrated in Fig. 4a–c. Figure 4a,b shows Coulomb blockade peak conductance as a function of back-gate voltage Vb, observed in device D1 at B=5.2 T, and D2 at B=7 T, respectively (see Methods for sample labelling key). Black points represent data and the red lines are fits used to extract peak positions. Figure 4c shows relative peak position, V(p)−V0, plotted as a function of peak number p for the first 10 peaks of Fig. 4a,b, where V(p) is the position of peak p in back-gate voltage, and V0 is the position of the first peak. Each data set is accompanied by a corresponding plot of  , where p and q are peak index numbers, representing the average peak spacing (black lines in Fig. 4c). The dot area extracted from quantized charge tunnelling is given by A=1/(β· ΔVb), where ΔVb is the back-gate voltage needed to increase dot occupation by one electron (Supplementary Table S1). A comparison of measured dot diameter,

, where p and q are peak index numbers, representing the average peak spacing (black lines in Fig. 4c). The dot area extracted from quantized charge tunnelling is given by A=1/(β· ΔVb), where ΔVb is the back-gate voltage needed to increase dot occupation by one electron (Supplementary Table S1). A comparison of measured dot diameter,  , with effective lithographic diameter,

, with effective lithographic diameter,  , indicates that d generally exceeds dlith. This is contrary to the reduced dimensions observed in GaAs dots, where smaller dimensions are observed because of depletion32.

, indicates that d generally exceeds dlith. This is contrary to the reduced dimensions observed in GaAs dots, where smaller dimensions are observed because of depletion32.

(a) Coulomb blockade peak conductance as a function of back-gate voltage Vb observed in device D1 at B=5.2 T. Black points represent data and the red line indicates a functional fit used to extract peak positions. The top-gate voltages are fixed at Vt1=11.402 V and Vt2=12 V.(b) Coulomb blockade in device D2 at B=7 T. The top-gate voltages are fixed at Vt1=Vt3=13 V and Vt2=Vt4=12 V. (c) Relative peak position, V(p)–V0, plotted as a function of peak number p for the first 10 peaks of (a) and (b). V(p) is the position of peak p in back-gate voltage Vb, and V0 is the position of the first peak (V0=−15.4907 V and −17.9875 V for plots (a) and (b), respectively). Each black line is a plot of  , where p and q are peak index numbers, representing the average peak spacing for the particular data set. Inset: simulated-dot size versus measured size. Error bars represent the range of diameters expected for measured Coulomb blockade peak spacings within 1 s.d. of the mean. (d) COMSOL simulation of density profile (in a.u.) for the lithographic gate pattern of device D4 for top-gate voltage Vt1=Vt2=12 V. Electron transport is restricted to resonant tunnelling events through the constrictions, indicated by the arrows.

, where p and q are peak index numbers, representing the average peak spacing for the particular data set. Inset: simulated-dot size versus measured size. Error bars represent the range of diameters expected for measured Coulomb blockade peak spacings within 1 s.d. of the mean. (d) COMSOL simulation of density profile (in a.u.) for the lithographic gate pattern of device D4 for top-gate voltage Vt1=Vt2=12 V. Electron transport is restricted to resonant tunnelling events through the constrictions, indicated by the arrows.

To obtain a better quantitative understanding of the discrepancy between lithographic and measured dot sizes, we use a commercial finite element analysis simulation tool (COMSOL) to calculate the expected dot area for each top-gate geometry. The spatial carrier density profile is modelled for a fixed top-gate potential by solving the Poisson equation assuming a metallic flake in free space (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. S7). This assumption is justified by local compressibility measurements of the v=0 state yielding  , which translates to a screening of 99% of the applied Vb voltage by the bilayer29. Remarkably, one may calculate dot size purely from gate geometry without relying on measured gap parameters. Assuming that charge accumulation in the quantum dot occurs when the carrier density exceeds a fixed cutoff d0, the dot size is defined as the area bounded by the intersection with the density distribution f(x,y) with the cutoff. Here the cutoff d0 is placed at the saddle points of the simulated density profile within the constrictions. This condition enables maximal tunnelling without loss of confinement, assuming that the tunnelling probability into the dot decays exponentially with barrier width. Moving the cutoff to densities far greater than d0 would pinch off the constrictions and suppress tunnelling, while placement far below d0 would lead to high barrier transparency and eventual loss of confinement. The simulated dot area from this method, plotted in Fig. 4c (inset), is simply the area bounded by the closed contour of f(x,y) at fixed density d0 (Supplementary Fig. S7). Alternatively, one may calculate dot size by imposing a cutoff equalling the measured gap width (Supplementary Table S2 and accounting for density offsets due to a displacement of the measurement voltage from the charge neutrality point (see Supplementary Discussion). The cutoffs extracted by these two models are equivalent to within δ n~1010 cm−2, the carrier density fluctuations due to disorder in our suspended bilayers (Supplementary Fig. S7)27.

, which translates to a screening of 99% of the applied Vb voltage by the bilayer29. Remarkably, one may calculate dot size purely from gate geometry without relying on measured gap parameters. Assuming that charge accumulation in the quantum dot occurs when the carrier density exceeds a fixed cutoff d0, the dot size is defined as the area bounded by the intersection with the density distribution f(x,y) with the cutoff. Here the cutoff d0 is placed at the saddle points of the simulated density profile within the constrictions. This condition enables maximal tunnelling without loss of confinement, assuming that the tunnelling probability into the dot decays exponentially with barrier width. Moving the cutoff to densities far greater than d0 would pinch off the constrictions and suppress tunnelling, while placement far below d0 would lead to high barrier transparency and eventual loss of confinement. The simulated dot area from this method, plotted in Fig. 4c (inset), is simply the area bounded by the closed contour of f(x,y) at fixed density d0 (Supplementary Fig. S7). Alternatively, one may calculate dot size by imposing a cutoff equalling the measured gap width (Supplementary Table S2 and accounting for density offsets due to a displacement of the measurement voltage from the charge neutrality point (see Supplementary Discussion). The cutoffs extracted by these two models are equivalent to within δ n~1010 cm−2, the carrier density fluctuations due to disorder in our suspended bilayers (Supplementary Fig. S7)27.

Discussion

Our model establishes a quantitative link between measured dot size and lithographic geometry and, therefore, may serve as a design tool for future bilayer nanodevices requiring submicron spatial control. These include double dot systems that form the basis of a spin-based quantum computer6. The production of suspended graphene quantum dots also enables study of coupling between quantized electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom33,34, with potential applications to nanoelectromechanical devices and the detection of quantized mechanical motion in a membrane35,36,37,38. Furthermore, the combination of high sample quality with local gating enables study of edge modes that emerge at the interface of broken symmetry quantum Hall states in an environment well-isolated from edge disorder (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Methods

Device fabrication

Following mechanical exfoliation of highly oriented pyrolytic graphite crystals, graphene is deposited on a 300-nm thermally grown SiO2 layer, which covers a doped silicon substrate functioning as a global back gate. Bilayer flakes are identified based on contrast to the substrate with an optical microscope and later verified through quantum Hall data. Cr/Au (3/100 nm) electrodes are defined on selected bilayers using electron beam (E-beam) lithography, thermal evaporation, and lift-off in acetone. A SiO2-spacer layer, ~150-nm thick is deposited with E-beam evaporation after a second lithography step. Local top gates are placed over the SiO2 spacers in a two-step E-beam lithography process. First, small features that define the tunnel barriers and constrictions are patterned using Cr/Au of thickness 3/75 nm, and thicker support structures constructed of 3/300 nm of Cr/Au that traverse the evaporated SiO2 step are deposited immediately afterwards. The devices are immersed in 5:1 buffered oxide etch for 90 s and dried in a critical point dryer, which leaves both the graphene and the top gates suspended.

Dot geometries and measurement conditions

We analyse five fully suspended quantum dots with lithographic diameters,  , of 150 to 450 nm. Listed here are details on individual sample geometries and measurement conditions. Device D1 is a circular two-gate dot with dlith= 400 nm measured at B=5.2 T with the valley polarized v=0 gap used for confinement. Device D2 is a circular dot with dlith=150 nm, consisting of three main gates with a plunger gate suspended above (Supplementary Fig. S1). Measurements were conducted at B=0 and 7 T with the E-field induced and v=0 gaps used for confinement, respectively. Device D3 is a circular four-gate dot with dlith=300 nm, measured at B=7 T. Device D4 is a circular four-gate dot with dlith= 400 nm measured at B=0 and 3 T. Device D5 is a two-gate elliptical dot with cross-sectional lengths of 200 and 250 nm measured at B=5 T. Additional scanning electron microscope images of locally gated quantum dot devices are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1. Top-gate labelling for devices D2 and D4 is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1 and Fig. 1, respectively. All measurements are conducted using standard Lockin techniques in a Leiden Cryogenics Model Minikelvin 126-TOF dilution refrigerator. A voltage bias set-up is used, where AC excitations ranging from 4–80 μV are applied at a frequency of 35.35 Hz with a 100 ms time constant. An electron temperature of T=110 mK is extracted from Coulomb blockade fits.

, of 150 to 450 nm. Listed here are details on individual sample geometries and measurement conditions. Device D1 is a circular two-gate dot with dlith= 400 nm measured at B=5.2 T with the valley polarized v=0 gap used for confinement. Device D2 is a circular dot with dlith=150 nm, consisting of three main gates with a plunger gate suspended above (Supplementary Fig. S1). Measurements were conducted at B=0 and 7 T with the E-field induced and v=0 gaps used for confinement, respectively. Device D3 is a circular four-gate dot with dlith=300 nm, measured at B=7 T. Device D4 is a circular four-gate dot with dlith= 400 nm measured at B=0 and 3 T. Device D5 is a two-gate elliptical dot with cross-sectional lengths of 200 and 250 nm measured at B=5 T. Additional scanning electron microscope images of locally gated quantum dot devices are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1. Top-gate labelling for devices D2 and D4 is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1 and Fig. 1, respectively. All measurements are conducted using standard Lockin techniques in a Leiden Cryogenics Model Minikelvin 126-TOF dilution refrigerator. A voltage bias set-up is used, where AC excitations ranging from 4–80 μV are applied at a frequency of 35.35 Hz with a 100 ms time constant. An electron temperature of T=110 mK is extracted from Coulomb blockade fits.

Despite the complex fabrication process required to make local gated devices, the graphene exhibits high quality as evidenced by symmetry breaking in the quantum Hall regime. Supplementary Fig. S2 contains Landau fans (measured in device D4 and in a two-gate split-gate device) plotted as conductance as a function of back-gate voltage Vb and magnetic field B, with zero voltage on the top gates. In the split-gate device, a map of quantized conductance as a function of the voltages on each split top gate is provided in Supplementary Fig. S2, where the voltage Vb=−3 V and field B=4 T are held constant. This provides evidence of local control over broken symmetry quantum Hall states in suspended bilayer graphene.

Measured dot size extracted from coulomb blockade fits

The dot area extracted from quantized charge tunnelling is given by  , where ΔVb is the back-gate voltage needed to increase dot occupation by 1 electron and β is the carrier density induced by 1 V on the back gate. The global density to voltage conversion is obtained by fitting Landau level filling factors v=nh/eB from bulk quantum Hall data. The peak spacing

, where ΔVb is the back-gate voltage needed to increase dot occupation by 1 electron and β is the carrier density induced by 1 V on the back gate. The global density to voltage conversion is obtained by fitting Landau level filling factors v=nh/eB from bulk quantum Hall data. The peak spacing  of a given data set is extracted by fitting each Coulomb blockade oscillation to the conductance expression:

of a given data set is extracted by fitting each Coulomb blockade oscillation to the conductance expression:

where e is the electron charge, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, A is peak amplitude, Vb,res, is the back-gate voltage at resonance, and a=Cg/(C1+Cr+Cg) is determined from the slopes of the Coulomb diamonds (Cg is capacitance to the back gate and C1 and Cr are capacitances across the left and right tunnel barriers, respectively). This expression is valid in the regime  , where ΔE is the single particle level spacing. This functional fit to the data is shown explicitly in Fig. 4a,b. Coulomb blockade data from an additional device is provided in Supplementary Fig. S4.

, where ΔE is the single particle level spacing. This functional fit to the data is shown explicitly in Fig. 4a,b. Coulomb blockade data from an additional device is provided in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Allen, M.T. et al. Gate-defined quantum confinement in suspended bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 3:934 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1945 (2012).

References

Meric, I. et al. Current saturation in zero-bandgap, top-gated graphene field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 654–659 (2008).

Stampfer, C. et al. Tunable Coulomb blockade in nanostructured graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 012102 (2008).

Ponomarenko, L. A. et al. Chaotic Dirac billiard in graphene quantum dots. Science 320, 356–358 (2008).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197–200 (2005).

CastroNeto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Trauzettel, B., Bulaev, D. V., Loss, D. & Burkard, G. Spin qubits in graphene quantum dots. Nat. Phys. 3, 192–196 (2007).

Khaetskii, A. V., Loss, D. & Glazman, L. Electron spin decoherence in quantum dots due to interaction with nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 186802 (2002).

Petta, J. R. et al. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science 309, 2180–2184 (2005).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Driven coherent oscillations of a single electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 442, 766–771 (2006).

Recher, P., Nilsson, J., Burkard, G. & Trauzettel, B. Bound states and magnetic field induced valley splitting in gate-tunable graphene quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 79, 085407 (2009).

Wu, G. Y., Lue, N. Y. & Chang, L. Graphene quantum dots for valley-based quantum computing: A feasibility study, Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1104.0443 (2011).

Culcer, D., Cywinski, L., Li, Q., Hu, X. & DasSarma, S. Quantum dot spin qubits in silicon: Multivalley physics. Phys. Rev. B 82, 155312 (2010).

Todd, K., Chou, H., Amasha, S. & Goldhaber-Gordon, D. Quantum dot behavior in graphene nanoconstrictions. Nano Lett. 9, 416–421 (2008).

Martin, J. et al. Observation of electron-hole puddles in graphene using a scanning single-electron transistor. Nat. Phys. 4, 144–148 (2008).

Molitor, F. et al. Transport through graphene double dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 222107 (2009).

Liu, X. L., Hug, D. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Gate-defined graphene double quantum dot and excited state spectroscopy. Nano. Lett. 10, 1623–1627 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. Graphene nanoribbons with smooth edges behave as quantum wires. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 563–567 (2011).

Pereira, J. M., Vasilopoulos, P. & Peeters, F. M. Tunable quantum dots in bilayer graphene. Nano Lett. 7, 946–949 (2007).

McCann, E. & Fal'ko, V. I. Landau-level degeneracy and quantum Hall effect in a graphite bilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 086805 (2006).

McCann, E. Asymmetry gap in the electronic band structure of bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 74, 161403 (2006).

Castro, E. V. et al. Biased bilayer graphene: Semiconductor with a gap tunable by the electric field effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 216802 (2007).

Oostinga, J. B., Heerche, H. B., Liu, X., Morpurgo, A. F. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Gate-induced insulating state in bilayer graphene devices. Nat. Mater. 7, 151–157 (2007).

Zhang, Y. et al. Direct observation of a widely tunable bandgap in bilayer graphene. Nature 459, 820–823 (2009).

Xia, F., Farmer, D. B., Lin, Y. & Avouris, P. Graphene field-effect transistors with high on/off current ratio and large transport band gap at room temperature. Nano. Lett. 10, 715–718 (2010).

Taychatanapat, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Electronic transport in dual-gated bilayer graphene at large displacement fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 166601 (2010).

Nomura, K. & MacDonald, A. H. Quantum Hall ferromagnetism in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 256602 (2006).

Feldman, B. E., Martin, J. & Yacoby, A. Broken symmetry states and divergent resistance in suspended bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 5, 889–893 (2009).

Zhao, Y., Cadden-Zimansky, P., Jiang, Z. & Kim, P. Symmetry breaking in the zero-energy Landau level in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 066801 (2010).

Martin, J., Feldman, B. E., Weitz, R. T., Allen, M. T. & Yacoby, A. Local compressibility measurements of correlated states in suspended bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 256806 (2010).

Weitz, R. T., Allen, M. T., Feldman, B. E., Martin, J. & Yacoby, A. Broken-symmetry states in doubly gated suspended bilayer graphene. Science 330, 812–816 (2010).

Martin, I., Morpurgo, Y. M. & Morpurgo, A. F. Topological confinement in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 036804 (2008).

Chklovskii, D. B., Shklovskii, B. I. & Glazman, L. I. Electrostatics of edge channels. Phys. Rev. B 46, 4026–4034 (1992).

Leturcq, R. et al. Franck Condon blockade in suspended carbon nanotube quantum dots. Nat. Phys. 5, 327–331 (2009).

Steele, G. A. et al. Strong coupling between single-electron tunneling and nanomechanical motion. Science 325, 1103–1107 (2009).

Shytov, A. V., Levitov, L. S. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Electromechanical noise in a diffusive conductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 228303 (2002).

LaHaye, M. D., Buu, O., Camarota, B. & Schwab, K. C. Approaching the quantum limit of a nanomechanical resonator. Science 304, 74–77 (2004).

Bunch, J. S. et al. Electromechanical resonators from graphene sheets. Science 315, 490–493 (2007).

Chen, C. et al. Performance of monolayer graphene nanomechanical resonators with electrical readout. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 861–867 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Feldman, O. Dial, H. Bluhm, and G. Ben-Shach for helpful discussions. This work is supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering under award DE-SC0001819, and by the 2009 U.S. ONR Multi University Research Initiative (MURI) on Graphene Advanced Terahertz Engineering (Gate) at MIT, Harvard, and Boston University. Nanofabrication was performed at the Harvard Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), a member of the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN) supported by NSF award ECS-0335765. M.T.A. acknowledges financial support from the DOE SCGF fellowship, administered by ORISE-ORAU under contract no. DE-AC05-06OR23100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T.A. contributed to sample design, fabricated the devices, carried out the experiments and data analysis, performed the simulations, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. J. M. contributed to sample design, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. A.Y. contributed to sample design, carried out the experiments and data analysis, performed the simulations, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S7, Supplementary Tables S1-S2, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 2325 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, M., Martin, J. & Yacoby, A. Gate-defined quantum confinement in suspended bilayer graphene. Nat Commun 3, 934 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1945

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1945

This article is cited by

-

Recent progresses of quantum confinement in graphene quantum dots

Frontiers of Physics (2022)

-

Flat band carrier confinement in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Cryogenic Materials and Circuit Integration for Quantum Computers

Journal of Electronic Materials (2020)

-

Large tunable valley splitting in edge-free graphene quantum dots on boron nitride

Nature Nanotechnology (2018)

-

Conductance quantization suppression in the quantum Hall regime

Nature Communications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.