Abstract

The arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal symbiosis is widely hypothesized to have promoted the evolution of land plants from rootless gametophytes to rooted sporophytes during the mid-Palaeozoic (480–360 Myr, ago), at a time coincident with a 90% fall in the atmospheric CO2 concentration ([CO2]a). Here we show using standardized dual isotopic tracers (14C and 33P) that AM symbiosis efficiency (defined as plant P gain per unit of C invested into fungi) of liverwort gametophytes declines, but increases in the sporophytes of vascular plants (ferns and angiosperms), at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a. These contrasting responses are associated with larger AM hyphal networks, and structural advances in vascular plant water-conducting systems, promoting P transport that enhances AM efficiency at 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a. Our results suggest that non-vascular land plants not only faced intense competition for light, as vascular land floras grew taller in the Palaeozoic, but also markedly reduced efficiency and total capture of P as [CO2]a fell.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi are among the most ancient and widespread obligate symbionts in contemporary floras, and are dependent on host plants for carbon, as they lack saprotrophic capabilities1. AM fungi are highly adapted to mobilize and translocate phosphorus (P) from beyond root depletion zones and from pores too small for entry by root hairs, in return for receiving photosynthate carbon1. Physiological adaptations include phosphate transporters within hyphal membranes with very high affinities for soil P, and phosphate transporters located in arbuscules that transfer P from the fungus to the plant cortex cells2. Phylogenetic relationships of mycorrhiza-specific genes coding for AM-inducible plant P transporters indicate their involvement in symbiotic P transport for hundreds of millions of years, with highly conserved regulation of gene expression2. The basis of the AM mutualism involves a stable cooperation between partners. Host plants preferentially reward fungal partners that provide greater access to P with photosynthate, and the fungi allocate P preferentially to plant partners providing a greater carbohydrate supply3.

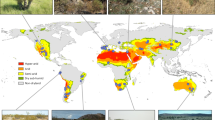

Phosphorus is an essential element required by plants for core metabolism (ATP) and growth (phospholipid membranes, RNA and DNA), and its low availability in soils is often a primary constraint on the productivity of terrestrial ecosystems4. This requirement has driven the establishment of symbiotic partnerships between soil-dwelling fungi and the earliest land plants (embryophytes) to increase the uptake of P ever since plants' initial conquest of the land5,6,7. Intercellular hyphae and arbuscules have been documented in gametophytes and sporophytes from the Early Devonian Rhynie chert flora, together with exceptionally well-preserved spores representative of several of the major glomeralean fungal groups8,9,10,11,12. These associations with AM fungi formed under a CO2-rich atmosphere, even before true roots evolved around 400 Myr, ago (Fig. 1).

(a) depicts land plant phylogeny (adapted from (refs. 47,48) and (b) the modelled global [CO2]a history (adapted from (ref. 24)) for the past 500 Myr, ago. Mapped onto the phylogeny is the occurrence of AM fungal associations across plant taxa*, and fossil evidence of AM fungi†. Species investigated in this work are highlighted in bold and pictured right. Dominant stages of plant life cycles are shown as 1 n (gametophyte) and 2 n (sporophyte).

The subsequent diversification of embryophytes in the mid-Palaeozoic (480–360 Myr, ago) is marked by the transition from a gametophyte-dominant generation lifecycle to one with an increasingly elaborate sporophyte-dominant generation, and the evolutionary appearance of roots, leaves and other innovations13. As terrestrial plants and ecosystems evolved, they progressively grew in stature, biomass, nutrient demand and rooting depth to extensively colonize uplifted continental land masses. The resulting increase in below-ground export of photosynthate carbon energy drove enhanced silicate rock weathering14, the development of soil profiles, pedogenic clay minerals15,16,17 and organic carbon burial18,19. Enhanced biological weathering from 410–340 Myr, ago is linked to a 90% reduction in the atmospheric CO2 concentration ([CO2]a) through the release of Ca and Mg from silicate minerals, and their export to the oceans where they were precipitated into carbonate sediments (Fig. 1)18,20. During the mid Palaeozoic, co-evolution of the AM fungal symbiosis and rooting systems likely had a pivotal role in provisioning the expanding biomass, stature and biogeography of forested ecosystems with their rising demand for essential soil nutrients. This would be especially important as P became increasingly limited owing to depletion of the primary mineral apatite (calcium phosphate) by chemical and biological weathering4,21 (Fig. 1).

Here we investigate the hypothesis that the evolutionary transition from non-vascular to vascular embryophytes with sporophyte-dominant lifecycles as Palaeozoic [CO2]a declined, drove changes in the plant–fungal cost benefits of the AM symbiosis. Our approach is based on the development and application of dual 33P and 14C isotope tracers to measure the reciprocal fluxes of carbon from plant-to-fungus, and phosphorus from fungus-to-plant. These fluxes are quantified using mesh-walled cores filled with soil set around the plants that can be colonized by AM hyphae but not plant roots or rhizoids. Static cores preserve intact hyphal networks running into the core, whereas rotated cores severe the network. AM symbiosis efficiency is defined as P gained by the plant through its fungal partners per unit of photosynthate carbon invested into the P absorbing hyphal network in the undisturbed mesh cores. This novel metric allows AM symbiosis efficiency to be determined for whole plants growing in natural soil, and facilitates comparisons across taxa and environments. Experiments were conducted with plant species representing three key nodes on the land plant evolutionary tree spanning several hundred million years of terrestrial ecosystem evolution (Fig. 1). These nodes encompass the critical transition from non-vascular plant gametophyte-dominant to vascular plant sporophyte-dominant lifecycles and appearance of true roots13. We investigated two species of basal non-vascular land plants (complex thalloid liverworts) with rhizoid systems (Preissia quadrata and Marchantia paleacea), grown either as prostrate mats of gametophytes (P. quadrata), or as individual gametophytes (M. paleacea). Both species of liverworts belong to the phylogenetic sub-group of Marchantiopsida22. Liverwort gametophyte [CO2]a responses were compared with those of the sporophytes of the basal vascular land plant Osmunda regalis, a fern with a well-developed rooting system, and the advanced angiosperm Plantago lanceolata, which has a coarse rooting system and high mycorrhizal dependency. DNA sequencing of the fungal partners within host root/thallus samples of our experimental plants confirmed they formed associations with AM fungi of the Glomeromycota (Fig 2). Plants were grown on skeletal nutrient-poor dune soil approximating the oligotrophic conditions of Palaeozoic terrestrial environments23 and at 1,500 p.p.m. and 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a as values representative of mid- and late-Palaeozoic atmospheres, respectively (Fig. 1)24. We found that AM symbiosis efficiency responds differently to a simulated Palaeozoic [CO2]a decline from 1,500 p.p.m. to 440 p.p.m.; decreasing in the most basal non-vascular land plant group (liverworts) and increasing in two vascular groups (ferns and angiosperms). These contrasting responses are associated with the structural advances in vascular plant water-conducting systems in roots and shoots enhancing physiological feedbacks that promote P translocation through the fungus and overall AM efficiency at 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a. Our experiments provide new insight into how the evolutionary advance from root-less gametophytes to rooted sporophytes increased the efficiency of biogeochemical cycling of P in soils during the 'greening of the Earth'.

Results

Plant and fungal C-fluxes respond to [CO2]a treatments

Over the 4-month duration of the experiments, the above-ground biomass of fern sporophytes was significantly (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=3.31, P<0.05) lower by 50% at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a, whereas the Preissia and Marchantia gametophytes, and the angiosperm sporophytes, showed no significant response to CO2 (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=3.31, P>0.05) (Fig. 3a). These biomass differences are linked to changes in plant carbon allocation to AM fungal networks inside the mesh-walled soil cores. One liverwort species, and both vascular plant species, exhibited significantly (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=40.18, P<0.05) lower (by over 90%) carbon allocation to the AM fungal networks colonizing the soil cores when grown at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a, as traced by 14CO2 supplied to the shoots (Fig. 3b). Plant carbon allocation to fungi therefore seems to be a [CO2]a-sensitive component of the AM symbiosis. Despite this reduced carbon investment in the AM networks, both liverworts and the fern pay a higher cost to support them at 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a, when calculated as the percentage 14CO2 fixed over a 12-h photoperiod (Fig. 3c).

Responses of (a) above-ground tissue biomass, (b) total carbon allocation to fungus within soil cores, (c) the percentage of total plant-fixed carbon allocated to fungus within soil cores, (d) the active hyphal length of fungi within soil cores and (e) active hyphal lengths in soil cores for the non-vascular and vascular plant species grown at 1,500 p.p.m. (black bars) or 440 p.p.m (white bars) [CO2]a. Bars with no letters in common are significantly different at P<0.05 (Tukey test after two-way ANOVA with species and [CO2]a and their interaction), whereas those sharing the same letters are not statistically significantly different P>0.05). Two-way ANOVA detected significant (P<0.01) effects of plant species in (a–d), and [CO2]a treatments in (a), (b) and (d) (P<0.05). Species×[CO2]a treatment interactions are significant in (a) and (b) (P<0.05), but not (c) and (d) (P>0.5). In all panels, means are shown ±1 s.e.m. (n=4).

Because AM fungi are obligate biotrophs dependent on their host plants for photosynthate energy1, we next determined how patterns of plant C allocation translated into changes in the size of the active nutrient-absorbing fungal network. Active mycorrhizal networks in soil cores were estimated as the difference in hyphal lengths per unit mass of soil between the static and rotated mesh cores. In general, changes in the size of active fungal lengths were less responsive to the two [CO2]a treatments than C allocation (Fig. 3d). Such modest [CO2]a effects on hyphal lengths may be due to persistence of severed hyphae in the rotated cores for which turnover times are uncertain and extremely difficult to determine25. In addition, although our estimates of the active hyphal network predominantly reflect changes in populations of mycorrhizal fungi, there will be a saprotrophic fungal component, which may partially obscure responses exclusively attributable to AM hyphae.

At the individual species–level, there was no significant (two-way ANOVA, F1,23=0.24, P> 0.05) effect of [CO2]a on active hyphal lengths, although there was a consistent trend for lower values in both liverwort species and the fern (Fig. 3d). However, pooling the data for each of the two types of plant (that is, non-vascular and vascular), revealed that the liverworts supported active hyphal lengths that were significantly (by 48%) smaller than those of the vascular plants at 1,500 p.p.m., and 63% lower at 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a (two-way ANOVA, F1,24=17.80, P<0.05 in both cases) (Fig. 3e). This finding is in keeping with the small size, prostrate habit, low productivity and absence of roots in the liverworts.

Fungal 33P uptake responds to [CO2]a treatments

We next examined the functionality of the fungal hyphal networks in the soil cores, as determined by their uptake and delivery of 33P from the cores to the plants (Fig. 4). Tissue concentrations of 33P (Fig. 4a) indicate that the sporophytes of both vascular plant taxa (fern and angiosperm) maintained fungal-acquired 33P uptake at 1,500 p.p.m. and 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a, despite significant (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=52.04, P<0.05) reductions in carbon allocation to the fungi inside the soil cores at the lower [CO2]a (Fig. 3b). In contrast, gametophytes of the liverwort P. quadrata showed dramatically lower (3–4 orders of magnitude) 33P uptake when grown at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a (Fig. 4a,b), linked to the reduced carbon investment into fungal mycelia (Fig. 3b). Similarly the second liverwort species, M. paleacea, also showed a significant (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=48.06, P<0.05) near 10-fold reduction in 33P uptake at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a.

Mean total 33P concentrations (ng g−1) in (a) above-ground tissues, (b) below-ground tissues and (c) within whole plants for each species at 1,500 p.p.m. (black bars) or 440 p.p.m. (white bars□) [CO2]a. Bars with no letters in common are significantly different at P<0.05 (Tukey test after two-way ANOVA with species and [CO2]a and their interaction), whereas those sharing the same letters are not statistically significantly different P>0.05). Two-way ANOVA detected significant (P<0.05) effects of plant species in (a–c), and [CO2]a treatments (P<0.001) in (a) and (c). Species×[CO2]a treatment interactions are significant in (a), (b) and (c) (P<0.01). In all panels, means are shown ±1 s.e.m. (n=4).

When comparing differences in P concentrations between taxa, it is important to recognize that the fern and angiosperm shoots are free of mycorrhizal fungi, whereas liverwort gametophyte thalli include fungal-colonized cells, which may retain 33P not transferred to the plant. To ensure comparability across taxa, therefore, we also calculated whole plant 33P concentrations by including its concentration in roots, where present, which can also retain 33P either in plant or fungal tissues (Fig. 4b). Calculated on this basis, the results support the finding that neither of the two vascular plant species showed significant reductions (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=69.02, P<0.05: Tukey multiple comparison between species and CO2P> 0.05) in 33P uptake at the lower growth [CO2]a, whereas it fell significantly (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=69.02, P<0.05) in both liverwort taxa (Fig. 4c).

AM symbiosis efficiency responds to [CO2]a treatments

We quantified the functional efficiency of the AM symbiosis based on the 14C and 33P tracer results, defined as total 33P taken up from the mesh-walled soil cores and transported into above-ground tissues (Fig. 4) per unit of photosynthate allocated to the AM fungal hyphae within these cores (Fig. 3), denoted as shoot 33P/C (Fig. 5). Calculated on this basis, there were strong differential responses of 33P/C AM efficiency to the two [CO2]a values with the evolution of plant lifecycles. Liverwort gametophytes exhibited 10- to 100-fold reductions in AM symbiosis efficiency at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a, which was significant (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=46.16, P<0.05) in Preissia, whereas both vascular plant taxa showed significant (two-way ANOVA, F3,23=46.16, P<0.05) 10- to 100-fold increases (Fig. 5).

Plant AM symbiosis efficiency measured as phosphorus-for-carbon efficiency (total P (ng)/total C(ng)) at 1,500 p.p.m. (black bars) or 440 p.p.m. (white bars□) [CO2]a. Bars sharing the same letters are not statistically significantly different (Tukey test after two-way ANOVA (species and [CO2]a treatments) P>0.05), whereas those with no letters in common are different at P<0.05. Two-way ANOVA detected significant effects of plant species (P<0.05), but not [CO2]a treatments (P=0.85). Species×[CO2]a treatment interaction is significant (P<0.001). In all panels, means are shown ±1 s.e.m (n=4).

Discussion

Extant liverworts are descended from embryophytes that diverged before tracheophytes appeared26. Comparative experiments between liverworts and tracheophyte lineages therefore provide a unique window into the physiological processes behind the early evolution of land plants. Under the high [CO2]a prevailing during the early stages of embryophyte colonization of the land24, gametophytes of two species of the basal non-vascular plant group (liverworts) operated with the highest AM symbiosis efficiency of all extant taxa investigated (Fig. 5). It effectively amplified the benefits of the AM symbiosis to these non-vascular 'lower' plants by reducing the carbon cost of fungal-acquired P from the soil (Fig. 5). Recent studies established that high [CO2]a and AM fungal colonization synergistically enhance the photosynthetic capacity, growth and reproductive fitness of liverworts6. Our new measurements of AM symbiosis efficiency provide further support reinforcing the hypothesis that the high [CO2]a of the early Palaeozoic created a strong selection pressure favouring the establishment of mycorrhiza-like partnerships with AM fungi in the gametophyte-dominant phase of rootless early land plants6,8,27.

Our experimental findings suggest that the dramatic fall in [CO2]a through the mid-Palaeozoic penalized the AM efficiency of non-vascular liverwort gametophytes, but enhanced it in more evolutionarily advanced vascular plant sporophytes. The differential nature of this AM symbiosis efficiency response across plant taxa quantified here (Fig. 5) is linked to the relative insensitivity of vascular plant 33P uptake via AM fungi between 1,500 and 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a and its sensitivity in liverworts (Fig. 4). This is associated with the large (14.8 m g−1) AM hyphal networks associated with the vascular plants showing little response to [CO2]a. However, the AM networks of liverworts, which were only half the length of those of the vascular plants (7.7 m g−1) at 1,500 p.p.m., showed a proportionally greater decline of 38% at 440 p.p.m. [CO2]a, although this was not significant (two-way ANOVA, F1,24=0.908, P>0.05) owing to high variance between replicates. Fungal P uptake kinetics are linked to hyphal network size. Both experimental evidence28,29,30 and theory31 indicate that inorganic P uptake by AM fungi follows Michaelis–Menton saturation kinetics, approaching an asymptote, as hyphal density in the soil increases. Further reductions in hyphal lengths from already low values in liverworts therefore result in very large declines in P uptake, not seen in the vascular plants with larger networks30.

Transpiration rates of leaves, and the translocation of P through fungal hyphae, are strongly linked to the mass flow of nutrients into the plants, increasing the effective region of P uptake around hyphae32. For example, maximum rates of transpiration of the herbaceous angiosperm Trifolium repens grown in association with the AM fungus Glomus mosseae increased total P translocation by the fungus to the host by >2-fold compared with plants with low transpiration rates32. Such plant physiological feedbacks operate, in part, by promoting replenishment of the immediate depletion zones around the AM hyphae, and reducing the energetic costs of active transport of P to the plant by cytoplasmic streaming through the fungal network1. In vascular plants from across a wide phylogenetic spectrum (including clubmosses, ferns and angiosperms), leaf stomatal size and density, and the resulting operational stomatal conductance to water vapour, are higher at 440 p.p.m. than at 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a33. This plasticity in vascular plant responses to lower [CO2]a, together with advances in water-conducting tissues, causes their transpiration rates to increase raising the efficiency of their AM hyphal networks. In contrast, the anatomically simpler liverworts, which grow appressed to their moist substrate, and lack the plasticity of tissue porosity in response to changing [CO2]a, have no apparent means of increasing the mass flow of nutrients into their thallus as [CO2]a falls.

In the context of the dramatic evolutionary changes that occurred in plants through the Palaeozoic [CO2]a decline13, these physiological effects promoting AM efficiency by enhancing soil P uptake, without requiring additional host plant C investment in fungi, were likely to be strongly reinforced. Major evolutionary innovations appeared including vascular tissues, progressively larger leaves with increasingly numerous stomata34,35, and deeper rooting systems36,37 enabling greater canopy transpiration and mass flow of nutrients from the soil solution into plants. By increasing mass transport of nutrients into roots with an expanding plant biomass, these innovations likely generated positive plant physiological feedback mechanisms progressively enhancing AM symbiosis efficiency by reducing the carbon cost to the host plants per unit of nutrient supplied via mycorrhiza. Such mechanisms are clearly not applicable to the ancestral and structurally simple gametophytes of early non-vascular land plants lacking both stomata and roots.

As burgeoning terrestrial floras began consuming the immediately accessible supplies of P on land making it increasingly scarce, they created strong selection pressures for more efficient plant–fungal AM symbiosis with a fall in Palaeozoic [CO2]a. Indeed, recent studies have highlighted a consistent property of ecosystem development over tens of thousands to millions of years is decreasing P availability, as it becomes locked up in recalcitrant secondary minerals and organic matter, and depleted via weathering, erosion and leaching21. Overall, these results imply that non-vascular land plants faced not only intense competition for light, as the evolving vascular land floras grew taller in the Palaeozoic13,38 but also experienced a greatly reduced efficiency and total capture of P with the fall in [CO2]a.

We conclude that increasing mycorrhizal symbiosis efficiency of land plants accompanied the well-documented evolution of key morphological innovations13 with a falling Palaeozoic [CO2]a, as they transitioned from gametophyte- to sporophyte-dominant lifecycles. Our results, obtained with experiments on extant taxa (Fig. 1), indicate that growth at 440 p.p.m. compared with 1,500 p.p.m. [CO2]a penalized both species of basal non-vascular land plant lineage by reducing the efficiency of their AM symbiosis (Fig. 5). At the same time, increasing sophistication in the form and function of vascular land plant shoots and roots enabled them to engage in a more efficient partnership with their obligate symbiotic fungal partners (Fig. 5) to meet the rising host plant demand for P uptake.

Quantification of AM efficiency for more species belonging to a broader suite of terrestrial plant lineages is required to better characterize how it changed, as Earth's floras and atmosphere evolved since the mid-Palaeozoic in partnership with symbiotic fungi to exploit soil phosphorus supplies. Nevertheless, our experimental evidence opens a new window on the consequences of plant–fungal evolution and [CO2]a change for biogeochemical cycles in the past. It indicates that the co-evolution of root–fungal symbioses during the origin and diversification of embryophytes is likely to have progressively increased the efficiency of biogeochemical cycling of P in soil ecosystems.

Methods

Plant species and growth conditions

Preissia quadrata and Plantago lanceolata plants were collected from Anglesey dune slacks (Grid Reference SH 397 648). Marchantia paleacea plants were originally collected from cool temperate cloud forests, Vera Cruz, Mexico and mycorrhizal gemmae propagated from adults maintained in controlled environment growth chambers. Mature Osmunda regalis sporophytes were obtained from Burncoose Nursery, Cornwall. Plants of all species were cultivated in large pots (2 litres) filled with native Anglesey dune soil that acted as a natural mycorrhizal inoculum. Plastic cores of 20 mm diameter and 90 mm long with 10 μm pore size nylon mesh windows in their outer walls were filled with calcareous grassland soil and we installed a 1-mm diameter perforated-capillary tube centrally down each one. Four of these cores were inserted into each pot (n=4 per species per [CO2]a treatment) to surround the roots or rhizoids. A further mesh-core filled with glass wool was inserted into each pot to enable below-ground gas sampling throughout the 14C labelling period.

Each species was grown under [CO2]a treatments of either 440 p.p.m. or 1,500 p.p.m. in controlled environment growth chambers (Conviron BDR16, Conviron, Canada). Each species was investigated with paired ambient and elevated [CO2]a treatments. All plants were maintained with 18 °C/15 °C day/night temperatures and a 12-h day length. Both P. lanceolata and O. regalis were grown under an irradiance of 200 μmol m−2 s−1, whereas P. quadrata and M. palaecea were grown at 50 μmol m−2 s−1, which represent half light-saturating conditions for the vascular and non-vascular plant groups, respectively39,40. Plants were acclimated to growth chamber conditions for 12 weeks to allow mycorrhizal fungi networks to establish between roots/rhizoids and the mesh-walled soil cores.

Molecular identification of fungal endosymbionts

We extracted genomic DNA from thallus and root samples of stock and experimental plants using established methods41, with a purification step using GeneClean (QBioGene). We then amplified (PicoMaxx, Stratagene or JumpStart, Sigma), cloned (TOPO TA, Invitrogen) and sequenced (BigDye v.3 on ABI3730 Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems) portions of fungal ribosomal RNA genes using nested-specific primer sets42 and the fungal primers ITS1F41 and ITS443 (GLOMBS1670 5′-AGCTTTAACCGGCATCTGT-3′ ; ITS1F 5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′; ITS4 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′; ITS4i 5′-TTGATATGCTTAAGTTCAGCG-3′; LETC1677 5′-CGGTGAGTAGCAATATTCG-3′; NS1 5′-GTAGTCATATGCTTGTCTC-3′; NS5 5′-AACTTAAAGGAATTGACGGAAG-3′; PARA1313 5′-CTAAATAGCCAGGCTGTTCTC-3′). We also screened and sequenced ca. 1600 bp of the fungal small ribosomal RNA gene using an approach described elsewhere44. Unique representative DNA sequences are deposited in GenBank Nucleotide Core database under accession numbers JQ811203–JQ811206. Phylogenetic analyses (Figure 2) were conducted with PAUP version 4.0b10 (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, Sinauer Associates, Massachusetts).

Quantifying reciprocal plant 33P for 14C exchange

Shoots were supplied with a pulse of 14CO2 for a 12-h photoperiod and 14C tracked through the AM fungal network colonizing soil-filled mesh-walled cylinders that exclude rhizoids and roots. The reciprocal assimilation and transport of inorganic P from fungus-to-plant in the same soil compartments was quantified by supplying 33P-orthophosphate into the mesh cores. In parallel control treatments, the cores were rotated to sever AM fungal network connections to the plants to account for diffusion of 14C into, and 33P out of, the cores. Standardized experimental design, [CO2]a treatments, substrates and measurement protocols were rigorously employed to ensure direct comparability for all species.

Following the acclimation period, we introduced 200 μl of 33P-labelled orthophosphoric acid (1 MBq) into two of the soil-filled cores via the installed capillary tube to ensure even distribution of the isotope in each pot for ambient and elevated [CO2]a-grown plant species. After 28 days, the soil cores were sealed with plastic caps and sterile anhydrous lanolin. The glass-wool-filled core was sealed using a gas-tight rubber septum (SubaSeal, Sigma) to allow non-destructive continuous monitoring by gas sampling of below-ground respiration. Each of the four replicate pots of mature plants for a particular [CO2]a treatment was then sealed into a gas-tight labelling chamber and 1.1 MBq 14C pulse label provided via liberation of 14CO2 from 15 μl Na14CO3 using 2 ml lactic acid introduced to the chamber. Pots with mesh cores were maintained under growth chamber conditions and 1 ml of labelling chamber gas sampled through the septa to monitor 14C drawdown after 1 h and every 4 h thereafter. One ml of gas from the glass wool-filled core in each pot was sampled after 1 h, and every 2 h thereafter to monitor below-ground respiration. Gas samples were injected into evacuated scintillation vials containing 10 ml Carbosorb (Perkin Elmer, Beaconsfield, UK) to trap CO2 and then 10 ml Permafluor scintillation cocktail (Perkin Elmer) was added. Radioactivity was measured via liquid scintillation counting (Packard Tri-carb 3100TR, Isotech).

Pots were left in situ until maximum 14C flux was detected in the glass wool-filled core (between 12–14 h post-labelling), at which point cores were removed from the pots and incubated in airtight containers with 2 ml 2 M KOH to trap respired 14C. Cores were transferred to fresh containers/KOH traps every 2 h for a further 6 h. From the KOH used to trap CO2, 1 ml was transferred to a scintillation vial with 10 ml Ultima Gold scintillation cocktail and the radioactivity monitored using liquid scintillation counting (Packard Tri-carb 3100TR, Isotech).

Plant harvest and tissue analysis

Upon removal of the soil cores from pots, all plant and soil material was separated into its constituent parts (that is, above-ground tissues, below-ground tissues, bulk soil), freeze dried and weighed.

Homogenized freeze-dried sample (10–30 mg of plant tissue or soil) was digested in 1 ml concentrated sulphuric acid and heated to 365 °C for 15 min. On cooling 100 μl hydrogen peroxide was added to each sample and reheated at 365 °C to produce a clear solution, which was diluted up to 10 ml with distilled water. We mixed 2 ml of diluted digest with 10 ml of the liquid scintillant (Emulsify-safe, Perkin-Elmer) for quantification of 33P activity (Packard Tri-carb 3100TR, Isotech). Precise 33P content was quantified using the following formula45:

where M33P=Mass of 33P (mg), cDPM=counts as disintegrations per minute, SAct=specific activity of the source (Bq mmol−1), Df=dilution factor and Mwt=molecular mass of P.

To quantify 14C present within each component of the experimental pots, between 10 and 100 mg dry weight (dw) tissue was placed in Combusto-cones (Perkin Elmer) and the 14C content measured through oxidation of each sample (Model 307 Packard Sample Oxidiser; Isotech). CO2 released through oxidation was trapped in 10 ml Carbosorb (Perkin Elmer) before being mixed with 10 ml Permafluor (Perkin Elmer). Radioactivity present in the sample was measured through liquid scintillation counting (Packard Tri-carb 3100TR, Isotech). Total C fixed by the plant and transferred to the AM fungal network was calculated as a function of the total volume and CO2 content of the labelling chamber and the proportion of the supplied 14CO2 label fixed by the plants. The difference in C between static cores and rotated cores is equivalent to the total C transferred from plant to symbiotic fungus within the soil core.

The total amount of C (12C and 14C) assimilated by the plant and transferred to the fungus46 was calculated using equations (2), (3) and (4):

where Tfp=total carbon transferred from fungus to plant (g); A=radioactivity of the tissue sample (Bq); Asp=specific activity of the source (Bq mol1) and ma=atomic mass of 14C (14).

where Pr=proportion of the total 14C label supplied present in the tissue; mc=mass of C in the CO2 present in the labelling chamber (g) (from the ideal gas law; equation (4)):

where mcd=mass of CO2 (g), Mcd=molecular mass of CO2 (44.01 g mol−1), P=pressure (kPa); Vcd=volume of CO2 in the chamber (0.003 m3); mc=mass of unlabelled C in the labelling chamber (g); M, molar mass (M of C=12.011 g); R=universal gas constant (J K−1 mol−1); T, absolute temperature (K); mc, mass of C in the CO2 present in the labelling chamber (g), where 0.27292 is the proportion of C in CO2 on a mass fraction basis, that is, 27.292%.

Statistical analyses

Differences between [CO2]a treatments and species were calculated and analysed with two-way ANOVA using additional post-hoc Tukey testing where appropriate (for example, species×CO2 interactions), in Minitab v12.21 (Minitab, US). Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were met through log10 transformations of variables where necessary.

Additional information

Accession codes: The sequencing data have been deposited in GenBank Nucleotide Core database under accession codes JQ811203 to JQ811206.

How to cite this article: Field, K.J. et al. Contrasting arbuscular mycorrhizal responses of vascular and non-vascular plants to a simulated Palaeozoic CO2 decline. Nat. Commun. 3:835 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1831 (2012).

References

Smith, S. E. & Read, D. J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. 3rd edn, (Academic Press, 2008).

Karandashov, V. & Bucher, M. Symbiotic phosphate transport in arbuscular mycorrhizas. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 22–29 (2005).

Kiers, E. T. et al. Reciprocal rewards stabilize cooperation in the mycorrhizal symbiosis. Science 333, 880–882 (2011).

Lambers, H., Raven, J. A., Shaver, G. R. & Smith, S. E. Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 95–103 (2008).

Brundrett, M. C. Coevolution of roots and mycorrhizas of land plants. New Phytol. 154, 275–304 (2002).

Humphreys, C. P. et al. Mutualistic mycorrhiza-like symbiosis in the most ancient group of land plants. Nat. Commun. 1, 103 (2010).

Wang, B. et al. Presence of three mycorrhizal genes in the common ancestor of land plants suggests a key role of mycorrhizas in the colonization of land by plants. New Phytol. 186, 514–525 (2010).

Remy, W., Taylor, T. N., Hass, H. & Kerp, H. Four-hundred-million-year-old vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11841–11843 (1994).

Taylor, T. N. & Krings, M. Fossil microorganisms and land plants: associations and interactions. Symbiosis 40, 119–135 (2005).

Krings, M. et al. Fungal endophytes in a 400-million-yr-old land plant: infection pathways, spatial distribution, and host responses. New Phytol. 174, 648–657 (2007).

Dotzler, N. et al. Acaulosporoid glomeromycotan spores with a germination shield from the 400-million-year-old Rhynie chert. Mycol. Prog. 8, 9–18 (2009).

Taylor, T. N., Kerp, H. & Hass, H. Life history biology of early land plants: Deciphering the gametophyte phase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5892–5897 (2005).

Kenrick, P. & Crane, P. R. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature 389, 33–39 (1997).

Berner, R. The Phanerozoic Carbon Cycle. (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Retallack, G. J. Early forest soils and their role in Devonian global change. Science 276, 583–585 (1997).

Elick, J. M., Driese, S. G. & Mora, C. I. Very large plant and root traces from the Early to Middle Devonian: Implications for early terrestrial ecosystems and atmospheric p(CO2). Geology 26, 143–146 (1998).

Kennedy, M., Droser, M., Mayer, L. M., Pevear, D. & Mrofka, D. Late Precambrian oxygenation; Inception of the clay mineral factory. Science 311, 1446–1449 (2006).

Berner, R. A. The carbon cycle and CO2 over Phanerozoic time: the role of land plants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B353, 75–81 (1998).

Beerling, D. J. & Berner, R. A. Feedbacks and the coevolution of plants and atmospheric CO2 . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 1302–1305 (2005).

Taylor, L. L. et al. Biological weathering and the long-term carbon cycle: integrating mycorrhizal evolution and function into the current paradigm. Geobiology 7, 171–191 (2009).

Peltzer, D. A. et al. Understanding ecosystem retrogression. Ecol. Monogr. 80, 509–529 (2010).

Shaw, J. & Renzaglia, K. Phylogeny and diversification of bryophytes. Am. J. Bot. 91, 1557–1581 (2004).

Raven, J. A., Andrews, M. & Quigg, A. The evolution of oligotrophy: implications for the breeding of crop plants for low input agricultural systems. Ann. Appl. Biol. 146, 261–280 (2005).

Berner, R. A. GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2 . Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5653–5664 (2006).

Leake, J. R. et al. Networks of power and influence: the role of mycorrhizal mycelium in controlling plant communities and agroecosystem functioning. Can. J. Bot. 82, 1016–1045 (2004).

Shaw, A. J., Szovenyi, P. & Shaw, B. Bryophtye diversity and evolution: Windows into the early evolution of land plants. Am. J. Bot. 98, 352–369 (2011).

Kidston, R. & Lang, W. H. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part V. The Thallophyta occurring in the peat-bed; the succession of the plants throughout a vertical section of the bed, and the conditions of accumulation and preservation of the deposit. T. Roy. Soc. Edin. 52, 855–902 (1921).

Li, X. L., George, E. & Marschner, H. Extension of the phosphorus depletion zone in VA-mycorrhizal white clover in a calcareous soil. Plant Soil 136, 41–48 (1991).

Li, X. L., Marschner, H. & George, E. Acquisition of phosphorus and copper by VA-mycorrhizal hyphae and root-to-shoot transport in white clover. Plant Soil 136, 49–57 (1991).

Li, X.- L., Eckhard, G. & Horst, M. Phosphorus depletion and pH decrease at the root-soil and hyphae-soil interfaces of VA mycorrhizal white clover fertilized with ammonlum. New Phytol. 119, 397–404 (1991).

Schnepf, A. & Roose, T. Modelling the contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to plant phosphate uptake. New Phytol. 171, 669–682 (2006).

Cooper, K. M. & Tinker, R. B. Translocation and transfer of nutrients in vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas IV. Effect of environmental variables on movement of phosphorus. New Phytol. 88, 327–339 (1980).

Franks, P. J., Leitch, I. J., Ruszala, E. M., Hetherington, A. M. & Beerling, D. J. Physiological framework for adaptation of stomata to CO2 from glacial to future concentrations. Phil. Trans. R Soc. B367, 537–546 (2012).

Beerling, D. J., Osborne, C. P. & Chaloner, W. G. Evolution of leaf-form in land plants linked to atmospheric CO2 decline in the Late Palaeozoic era. Nature 410, 352–354 (2001).

Osborne, C. P., Beerling, D. J., Lomax, B. H. & Chaloner, W. G. Biophysical constraints on the origin of leaves inferred from the fossil record. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10360–10362 (2004).

Algeo, T. J. & Scheckler, S. E. Terrestrial-marine teleconnections in the Devonian: links between the evolution of land plants, weathering processes, and marine anoxic events. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 353, 113–128 (1998).

Raven, J. A. & Edwards, D. Roots: evolutionary origins and biogeochemical significance. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 381–401 (2001).

Chaloner, W. G. & Sheerin, A. Devonian macro floras. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 145–161 (1979).

Fletcher, B. J., Brentnall, S. J., Quick, W. P. & Beerling, D. J. BRYOCARB: A process-based model of thallose liverwort carbon isotope fractionation in response to CO2, O2, light and temperature. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5676–5691 (2006).

Nobel, P. S. Physicochemical and environmental plant physiology. 2nd edn. (Academic Press, 1999).

Gardes, M. & Bruns, T. D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 2, 113–118 (1993).

Hijri, I. et al. Communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in arable soils are not necessarily low in diversity. Mol. Ecol. 15, 2277–2289 (2006).

White, T. J., Bruns, T. D., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. W. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications 315–322 (Academic Press, 1990).

Bidartondo, M. I. et al. The dawn of symbiosis between plants and fungi. Biol. Letters 7, 574–577 (2011).

Cameron, D. D., Leake, J. R. & Read, D. J. Mutualistic mycorrhiza in orchids: evidence from plant-fungus carbon and nitrogen transfers in the green-leaved terrestrial orchid Goodyera repens. New Phytol. 171, 405–416 (2006).

Cameron, D. D., Johnson, I., Read, D. J. & Leake, J. R. Giving and receiving: measuring the carbon cost of mycorrhizas in the green orchid, Goodyera repens. New Phytol. 180, 176–184 (2008).

Bonfante, P. & Genre, A. Plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: an evolutionary-developmental perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 492–498 (2008).

Qiu, Y. L. et al. A nonflowering land plant phylogeny inferred from nucleotide sequences of seven chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear genes. Int. J. Plant Sci. 168, 691–708 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Nigel Brown at Treborth Botanic Gardens, Bangor for expert advice on plant care and access to field sites, Sir David Read for discussions and advice, Claire Humphreys for assistance with the Marchantia paleacea tracer experiments, Joe Quirk for help with images and Irene Johnson for technical assistance throughout the project. We acknowledge funding through an NERC award (NE/F019033/1) and an NERC/World Universities Network Weathering Consortium award (NE/C521001/1). D.J.B. gratefully acknowledges funding through a Royal Society Wolfson-Research Merit Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.F., D.D.C., J.R.L. and D.J.B. conceived and designed the investigation. K.J.F. and S.T. undertook the research, and K.J.F., D.D.C., J.R.L. and D.J.B. analysed and interpreted the data sets. M.I.B. undertook the molecular DNA identification of the AM fungi. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript written by D.J.B., J.R.L. and K.J.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Field, K., Cameron, D., Leake, J. et al. Contrasting arbuscular mycorrhizal responses of vascular and non-vascular plants to a simulated Palaeozoic CO2 decline. Nat Commun 3, 835 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1831

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1831

This article is cited by

-

Microbes modify soil nutrient availability and mediate plant responses to elevated CO2

Plant and Soil (2023)

-

Correlative Microscopy: a tool for understanding soil weathering in modern analogues of early terrestrial biospheres

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Carbon for nutrient exchange between Lycopodiella inundata and Mucoromycotina fine root endophytes is unresponsive to high atmospheric CO2

Mycorrhiza (2021)

-

Impacts of elevated atmospheric CO2 on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their role in moderating plant allometric partitioning

Mycorrhiza (2021)

-

The distribution and evolution of fungal symbioses in ancient lineages of land plants

Mycorrhiza (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.