Abstract

A topological insulator protected by time-reversal symmetry is realized via spin–orbit interaction-driven band inversion. The topological phase in the Bi1−xSbx system is due to an odd number of band inversions. A related spin–orbit system, the Pb1−xSnxTe, has long been known to contain an even number of inversions based on band theory. Here we experimentally investigate the possibility of a mirror symmetry-protected topological crystalline insulator phase in the Pb1−xSnxTe class of materials that has been theoretically predicted to exist in its end compound SnTe. Our experimental results show that at a finite Pb composition above the topological inversion phase transition, the surface exhibits even number of spin-polarized Dirac cone states revealing mirror-protected topological order distinct from that observed in Bi1−xSbx. Our observation of the spin-polarized Dirac surface states in the inverted Pb1−xSnxTe and their absence in the non-inverted compounds related via a topological phase transition provide the experimental groundwork for opening the research on novel topological order in quantum devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological insulators are band insulators are featuring uniquely spin-polarized surface states, which is believed to be a consequence of odd number of inversions of bulk bands driven by spin–orbit interaction alone or in combination with crystal lattice modulations1,2,3,4,5. The odd number of band inversion transitions in the bulk demarcate a Z2 topological insulator (TI) phase with spin-polarized surface states from that of a conventional band insulator phase, as previously demonstrated in TI Bi1−xSbx and the Bi2Se3 series1,2,3,4,5. Within band theoretical calculations, lead tin telluride Pb1−xSnxTe, which is a narrow band gap semiconductor widely used for infrared optoelectronic and thermoelectric devices6,7, has long been known to contain an even number of band inversions as electronic structure is tuned via the Sn/Pb ratio8,9,10,11,12,13. Theoretical calculations have also predicted the occurrence of surface or interface states within the inverted band gap upon the band inversion transition11,12,13 but no experimental evidence of the surface states has been reported so far. Recent theoretical works14,15 have further stimulated the experimental search for surface states in Pb1−xSnxTe. In a recent calculation15, Hsieh et al. predicted that the topological surface states in SnTe15 are protected by crystalline space group symmetries, in contrast to the time-reversal symmetry protection in the well-known Z2 TIs.

The crystal group symmetry of Pb1−xSnxTe, critical for the realization of the topological crystalline insulator (TCI) phase14, is based on the sodium chloride structure (space group Fm m (225)). In this structure, each of the two atom types (Pb/Sn, or Te) forms a separate face-centred cubic lattice, with the two lattices interpenetrating so as to form a three-dimensional checkerboard pattern. The first Brillouin zone (BZ) of the crystal structure is a truncated octahedron with six square faces and eight hexagonal faces. The band gap of Pb1−xSnxTe is found to be a direct gap located at the L points in the BZ8, which are the centres of the eight hexagonal faces of the BZ. Owing to the inversion symmetry of the crystal, each L point and its diametrically opposite partner on the BZ are completely equivalent. Thus, there are four distinct L point momenta. It is well established that the band inversion transitions in the Pb1−xSnxTe take place at these four L points of the BZ9,10,11,12,13. As a result, even number of (four) inversions exclude the system from being a Kane–Mele Z2 TI2. However, it is interesting to note that the momentum space locations of the band inversions are coincident with the momentum space mirror plane within the BZ. This fact provides a clue that band inversions in Pb1−xSnxTe may lead to a distinct topologically nontrivial phase that is irrelevant to the time-reversal symmetry but may be the consequence of the spatial mirror symmetries of the crystal, which has been theoretically shown in the inverted end compound SnTe15. However, it is experimentally known that SnTe crystals actually are subjected to a rhombohedral distortion16, which, strictly speaking, breaks the crystal mirror symmetries and hence excludes a gapless TCI phase15. More importantly, SnTe crystals are typically heavily p-type17 due to the fact that Sn vacancies are thermodynamically stable17, which makes the chemical potential of SnTe to lie below the bulk valence band maximum (VBM), consequently not cutting across the surface states. The surface states, which may exist within the band gap, are thus unoccupied and cannot be experimentally studied by photoemission experiments18. On the other hand, the Pb-rich samples are reported to possess the ideal (averaged) sodium chloride structure without global rhombohedral distortion16, which thus preserve the proper crystal symmetry required for the predicted TCI phase15. Moreover, it is possible to grow Pb-rich crystals in which the chemical potential can be brought up above the bulk VBM (in-gap or even n-type)19, so as to lie near the surface state Dirac point.

m (225)). In this structure, each of the two atom types (Pb/Sn, or Te) forms a separate face-centred cubic lattice, with the two lattices interpenetrating so as to form a three-dimensional checkerboard pattern. The first Brillouin zone (BZ) of the crystal structure is a truncated octahedron with six square faces and eight hexagonal faces. The band gap of Pb1−xSnxTe is found to be a direct gap located at the L points in the BZ8, which are the centres of the eight hexagonal faces of the BZ. Owing to the inversion symmetry of the crystal, each L point and its diametrically opposite partner on the BZ are completely equivalent. Thus, there are four distinct L point momenta. It is well established that the band inversion transitions in the Pb1−xSnxTe take place at these four L points of the BZ9,10,11,12,13. As a result, even number of (four) inversions exclude the system from being a Kane–Mele Z2 TI2. However, it is interesting to note that the momentum space locations of the band inversions are coincident with the momentum space mirror plane within the BZ. This fact provides a clue that band inversions in Pb1−xSnxTe may lead to a distinct topologically nontrivial phase that is irrelevant to the time-reversal symmetry but may be the consequence of the spatial mirror symmetries of the crystal, which has been theoretically shown in the inverted end compound SnTe15. However, it is experimentally known that SnTe crystals actually are subjected to a rhombohedral distortion16, which, strictly speaking, breaks the crystal mirror symmetries and hence excludes a gapless TCI phase15. More importantly, SnTe crystals are typically heavily p-type17 due to the fact that Sn vacancies are thermodynamically stable17, which makes the chemical potential of SnTe to lie below the bulk valence band maximum (VBM), consequently not cutting across the surface states. The surface states, which may exist within the band gap, are thus unoccupied and cannot be experimentally studied by photoemission experiments18. On the other hand, the Pb-rich samples are reported to possess the ideal (averaged) sodium chloride structure without global rhombohedral distortion16, which thus preserve the proper crystal symmetry required for the predicted TCI phase15. Moreover, it is possible to grow Pb-rich crystals in which the chemical potential can be brought up above the bulk VBM (in-gap or even n-type)19, so as to lie near the surface state Dirac point.

Therefore, to experimentally investigate the possibility of a topological phase transition, and thus rigorously proving the existence of a TCI phase in the Pb1−xSnxTe system, we hereby utilize angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) and spin-resolved ARPES to study the low-energy electronic structure below and above the band inversion topological transition in the Pb-rich compositional range of the system, through which the observation of spin-polarized surface states in the inverted regime and their absence in the non-inverted regime is demonstrated, correlating the observed spin-polarized Dirac surface states with the expected band inversion topological phase transition. We further map out the critically important spin structure of the surface states protected by mirror symmetries in the inverted topological composition. These results show that the topological order observed in Pb1−xSnxTe is distinct from that previously discovered in Bi1−xSbx or Bi2Se3 (refs 1,2,3,4,5). Our spin-resolved study of Pb1−xSnxTe paves the way for further investigation of many novel properties of topological crystalline order14,20,21,22 in real materials and devices.

Results

Comparison of non-inverted and inverted compositions

To capture the electronic structure both below and above the band inversion transition (theoretically predicted to be around x 1/3 (refs 9, 10), we choose two representative compositions, namely x=0.2 and x=0.4, for detailed systematic studies. Figure 1c shows the momentum-integrated core level photoemission spectra for both compositions, where intensity peaks corresponding to tellurium 4d, tin 4d and lead 5d orbitals are observed. The energy splitting of the Pb orbital is observed to be larger than that of the Sn orbital, which is consistent with the stronger spin–orbit coupling of the heavier Pb nuclei. In addition, the spectral intensity contribution of the Sn peaks in the x=0.4 sample (red) is found to be higher than that of in the x=0.2 sample (blue), which is also consistent with the larger Sn concentration in the x=0.4 samples. We perform systematic low-energy electronic structure studies on these two representative compositions. As the low-energy physics of the system is dominated by the band inversion at L points (L points projected onto

1/3 (refs 9, 10), we choose two representative compositions, namely x=0.2 and x=0.4, for detailed systematic studies. Figure 1c shows the momentum-integrated core level photoemission spectra for both compositions, where intensity peaks corresponding to tellurium 4d, tin 4d and lead 5d orbitals are observed. The energy splitting of the Pb orbital is observed to be larger than that of the Sn orbital, which is consistent with the stronger spin–orbit coupling of the heavier Pb nuclei. In addition, the spectral intensity contribution of the Sn peaks in the x=0.4 sample (red) is found to be higher than that of in the x=0.2 sample (blue), which is also consistent with the larger Sn concentration in the x=0.4 samples. We perform systematic low-energy electronic structure studies on these two representative compositions. As the low-energy physics of the system is dominated by the band inversion at L points (L points projected onto  points on the (001) surface), we present ARPES measurements with the momentum space window centred at the

points on the (001) surface), we present ARPES measurements with the momentum space window centred at the  point, which is the midpoint of the surface BZ edge (see Fig. 1b). Figures 2a show the ARPES Fermi surface and dispersion mappings of the Pb0.8Sn0.2Te sample (x=0.2). The system at x=0.2 is observed to be gapped: No band is observed to cross the Fermi level in the Fermi surface maps (Fig. 2a). The dispersion measurements (Fig. 2b) reveal a single hole-like band below the Fermi level. This single hole-like band is observed to show strong dependence with respect to the incident photon energy (see Fig. 2b, and also detailed in Supplementary Figs S1–S3 and Supplementary Methods in the Supplementary Information), which reflects its three-dimensionally dispersive bulk valence band origin. As a qualitative guide to the ARPES measurements on x=0.2, we present first-principles-based electronic structure calculation on the non-inverted end compound PbTe (Fig. 2c). Our calculations confirm that PbTe is a conventional band insulator, whose electronic structure can be described as a single hole-like bulk valence band in the vicinity of each

point, which is the midpoint of the surface BZ edge (see Fig. 1b). Figures 2a show the ARPES Fermi surface and dispersion mappings of the Pb0.8Sn0.2Te sample (x=0.2). The system at x=0.2 is observed to be gapped: No band is observed to cross the Fermi level in the Fermi surface maps (Fig. 2a). The dispersion measurements (Fig. 2b) reveal a single hole-like band below the Fermi level. This single hole-like band is observed to show strong dependence with respect to the incident photon energy (see Fig. 2b, and also detailed in Supplementary Figs S1–S3 and Supplementary Methods in the Supplementary Information), which reflects its three-dimensionally dispersive bulk valence band origin. As a qualitative guide to the ARPES measurements on x=0.2, we present first-principles-based electronic structure calculation on the non-inverted end compound PbTe (Fig. 2c). Our calculations confirm that PbTe is a conventional band insulator, whose electronic structure can be described as a single hole-like bulk valence band in the vicinity of each  point, which is consistent with our ARPES results on Pb-rich Pb0.8Sn0.2Te. The three-dimensional nature of the calculated bulk valence band is revealed by its kz evolution in Fig. 2c, which is in qualitative agreement with the incident photon energy dependence of our ARPES measurements shown in Fig. 2b.

point, which is consistent with our ARPES results on Pb-rich Pb0.8Sn0.2Te. The three-dimensional nature of the calculated bulk valence band is revealed by its kz evolution in Fig. 2c, which is in qualitative agreement with the incident photon energy dependence of our ARPES measurements shown in Fig. 2b.

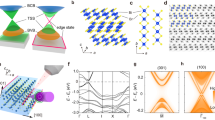

(a) The lattice of Pb1−xSnxTe system is based on the sodium chloride crystal structure. (b) The first BZ of Pb1−xSnxTe. The mirror planes are shown using green and light-brown colours. These mirror planes project onto the (001) crystal surface as the  mirror lines (shown by red solid lines). (c) ARPES measured core level spectra (incident photon energy 75 eV) of two representative compositions, namely Pb0.8Sn0.2Te and Pb0.6Sn0.4Te. The photoemission core levels of tellurium 4d, tin 4d and lead 5d orbitals are observed. (d) The bulk band gap of Pb1−xSnxTe alloy system undergoes a band inversion upon changing the Pb/Sn ratio8,9,10. A TCI phase with metallic surface states is theoretically predicted when the band gap is inverted (towards SnTe)15. The lowest-lying conduction and valence states associated with odd and even parity eigenvalues are labelled by L6− and L6+, respectively. First-principles-based calculation of band dispersion (e) and iso-energetic contour with energy set at 0.02 eV below the Dirac node energy (f) of the inverted end compound SnTe as a qualitative reference for the ARPES experiments. The surface states are shown by the red lines whereas the bulk band projections are represented by the green shaded area in e.

mirror lines (shown by red solid lines). (c) ARPES measured core level spectra (incident photon energy 75 eV) of two representative compositions, namely Pb0.8Sn0.2Te and Pb0.6Sn0.4Te. The photoemission core levels of tellurium 4d, tin 4d and lead 5d orbitals are observed. (d) The bulk band gap of Pb1−xSnxTe alloy system undergoes a band inversion upon changing the Pb/Sn ratio8,9,10. A TCI phase with metallic surface states is theoretically predicted when the band gap is inverted (towards SnTe)15. The lowest-lying conduction and valence states associated with odd and even parity eigenvalues are labelled by L6− and L6+, respectively. First-principles-based calculation of band dispersion (e) and iso-energetic contour with energy set at 0.02 eV below the Dirac node energy (f) of the inverted end compound SnTe as a qualitative reference for the ARPES experiments. The surface states are shown by the red lines whereas the bulk band projections are represented by the green shaded area in e.

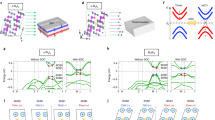

(a,b) ARPES low-energy electronic structure measurements on Pb0.8Sn0.2Te (x=0.2). (c) First-principles calculated electronic structure of PbTe (x=0) as a qualitative guide to the ARPES measurements on Pb0.8Sn0.2Te. PbTe, which lies on the non-inverted regime, is theoretically expected to be a conventional band insulator15. (d,e) ARPES low-energy electronic structure measurements on Pb0.6Sn0.4Te (x=0.4) under identical experimental conditions and setups as in a and b. (f) First-principles calculated electronic structure of SnTe (x=1) as a qualitative guide to the ARPES measurements on Pb0.6Sn0.4Te. SnTe, which lies on the inverted regime, is theoretically expected to be a topological crystalline insulater15. The insets of a and d show the non-inverted and inverted bulk band gap of the x=0.2 and x=0.4 samples, respectively. The blue and red lines in c and f are the calculated dispersion of the bulk bands and the surface states, respectively.

Now we present comparative ARPES measurements under identical experimental conditions and setups on the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te (x=0.4) sample. In contrast to the conventional band insulator (insulating) behaviour in the x=0.2 sample, the Fermi surface mapping (Fig. 2d) on the x=0.4 sample shows two unconnected metallic Fermi pockets (dots) on the opposite sides of the  point. Such two-pockets Fermi surface topology cannot be easily interpreted as the bulk valence band as the low-energy bulk valence band of the Pb1−xSnxTe system is a single hole-like band, unless certain surface-umklapp processes of the bulk states are considered, which usually have only weak cross-section in ARPES measurements. The assignment of the observed two-Fermi-pockets as surface-umklapp processes or other bulk-related origins can be further ruled out by incident photon energy dependence (kz dispersion) measurements and our spin polarization studies of these metallic states (see Supplementary Figs S1–S5 in the Supplementary Information). The dispersion measurements on the x=0.4 sample are shown in Fig. 2e. The single hole-like bulk valence band, which is similar to that in the x=0.2 sample, is also observed below the Fermi level. More importantly, a pair of metallic states crossing the Fermi level on the opposite sides of the

point. Such two-pockets Fermi surface topology cannot be easily interpreted as the bulk valence band as the low-energy bulk valence band of the Pb1−xSnxTe system is a single hole-like band, unless certain surface-umklapp processes of the bulk states are considered, which usually have only weak cross-section in ARPES measurements. The assignment of the observed two-Fermi-pockets as surface-umklapp processes or other bulk-related origins can be further ruled out by incident photon energy dependence (kz dispersion) measurements and our spin polarization studies of these metallic states (see Supplementary Figs S1–S5 in the Supplementary Information). The dispersion measurements on the x=0.4 sample are shown in Fig. 2e. The single hole-like bulk valence band, which is similar to that in the x=0.2 sample, is also observed below the Fermi level. More importantly, a pair of metallic states crossing the Fermi level on the opposite sides of the  point is observed along the

point is observed along the  mirror line momentum space direction. These states are found to show no observable dispersion upon varying the incident photon energy (further details in Supplementary Fig. S3), reflecting its two-dimensional character. On the other hand, the single hole-like band is observed to disperse strongly upon varying the incident photon energy, suggesting its three-dimensional character. At a set of different photon energy (kz) values, the bulk valence band intensity overlaps (intermixing) with different parts of the surface states in energy and momentum space. At a photon energy of 18 eV, the intermixing (intensity overlap) is strong, and the inner two branches of the surface states are masked by the bulk intensity. At photon energies of 10 and 24 eV, the surface states are found to be relatively better isolated. These ARPES measurements suggest that the x=0.4 sample lies on the inverted composition regime and that the observed surface states are related to the band inversion transition in Pb1−xSnxTe as predicted theoretically11,12,13,15. As a qualitative guide, we present first-principles-based electronic structure calculation on the inverted end compound SnTe (Fig. 2f). The calculated electronic structure of SnTe is found to be a superposition of two kz nondispersive metallic surface states and a single hole-like kz dispersive bulk valence band in the vicinity of the

mirror line momentum space direction. These states are found to show no observable dispersion upon varying the incident photon energy (further details in Supplementary Fig. S3), reflecting its two-dimensional character. On the other hand, the single hole-like band is observed to disperse strongly upon varying the incident photon energy, suggesting its three-dimensional character. At a set of different photon energy (kz) values, the bulk valence band intensity overlaps (intermixing) with different parts of the surface states in energy and momentum space. At a photon energy of 18 eV, the intermixing (intensity overlap) is strong, and the inner two branches of the surface states are masked by the bulk intensity. At photon energies of 10 and 24 eV, the surface states are found to be relatively better isolated. These ARPES measurements suggest that the x=0.4 sample lies on the inverted composition regime and that the observed surface states are related to the band inversion transition in Pb1−xSnxTe as predicted theoretically11,12,13,15. As a qualitative guide, we present first-principles-based electronic structure calculation on the inverted end compound SnTe (Fig. 2f). The calculated electronic structure of SnTe is found to be a superposition of two kz nondispersive metallic surface states and a single hole-like kz dispersive bulk valence band in the vicinity of the  point, which is in qualitative agreement with the ARPES results on Pb0.6Sn0.4Te.

point, which is in qualitative agreement with the ARPES results on Pb0.6Sn0.4Te.

Surface state topology of Pb0.6Sn0.4Te

We now perform systematic measurements on the surface electronic structure of the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te. Figure 3b shows the wide range Fermi surface mapping covering the first surface BZ. The surface states are observed to be present, and only present, along the mirror line ( ) directions. No other states are found along any other momentum directions on the Fermi level. In close vicinity to each

) directions. No other states are found along any other momentum directions on the Fermi level. In close vicinity to each  point, a pair of surface states are observed along the mirror line direction. One lies inside the first surface BZ whereas the other is located outside. Therefore, in total four surface states are observed within the first surface BZ, in agreement with the fact that there are four band inversions in Pb1−xSnxTe. The mapping zoomed-in near the

point, a pair of surface states are observed along the mirror line direction. One lies inside the first surface BZ whereas the other is located outside. Therefore, in total four surface states are observed within the first surface BZ, in agreement with the fact that there are four band inversions in Pb1−xSnxTe. The mapping zoomed-in near the  point (Fig. 3c) reveals two unconnected small pockets (dots). The momentum space distance from the centre of each pocket to the

point (Fig. 3c) reveals two unconnected small pockets (dots). The momentum space distance from the centre of each pocket to the  point is about 0.09 Å−1. Dispersion measurements (EB vs k) are performed along three important momentum space cuts, namely cuts 1, 2 and 3 defined in Fig. 3c, to further reveal the electronic structure of the surface states. Metallic surface states crossing the Fermi level are observed in both cuts 1 and 2, whereas cut 3 is found to be fully gapped, which is consistent with the theoretically calculated surface states electronic structure shown in Fig. 1e. In cut 1 (Fig. 3d), which is the mirror line (

point is about 0.09 Å−1. Dispersion measurements (EB vs k) are performed along three important momentum space cuts, namely cuts 1, 2 and 3 defined in Fig. 3c, to further reveal the electronic structure of the surface states. Metallic surface states crossing the Fermi level are observed in both cuts 1 and 2, whereas cut 3 is found to be fully gapped, which is consistent with the theoretically calculated surface states electronic structure shown in Fig. 1e. In cut 1 (Fig. 3d), which is the mirror line ( ) direction, a pair of surface states are observed on the Fermi level. The surface states in our Pb0.6Sn0.4Te samples are found to have a relatively broad spectrum, which can be possibly understood by the strong scattering in the disordered alloy system similar to the broad spectrum of the topological surface states in the Bi1−xSbx alloy23. In addition to the scattering broadening, the surface states are also observed to tail on the very strong main valence band emission (for example, the white region of intensity distribution in Fig. 3d). In the case of Fig. 2e (photon energy of 24 eV), the bulk VBM locates outside the first surface BZ. The surface state inside the first surface BZ is relatively better isolated from the bulk bands as compared with the one outside the first surface BZ. We thus study the dispersion along cut 2 (Fig. 3d), which only cuts across the surface states inside the first surface BZ. Both the dispersion maps and the momentum distribution curves in cut 2 reveal that the surface states along cut 2 are nearly Dirac-like (linearly dispersive) close to the Fermi level. In many TIs, the surface states deviate from ideal linearity24. Fitting of the momentum distribution curves of cut 2 (see Supplementary Fig. S6 for data analysis) shows that the experimental chemical potential (EF) lies roughly at (or just below) the Dirac point energy (ED), EF=ED±0.02 eV. The surface states' velocity is obtained to be 2.8±0.1 eV Å (4.2±0.2 × 105 m s−1) along cut 2, and 1.1±0.3 eV Å (1.7±0.4 × 105 m s−1) for the two outer branches along cut 1, respectively.

) direction, a pair of surface states are observed on the Fermi level. The surface states in our Pb0.6Sn0.4Te samples are found to have a relatively broad spectrum, which can be possibly understood by the strong scattering in the disordered alloy system similar to the broad spectrum of the topological surface states in the Bi1−xSbx alloy23. In addition to the scattering broadening, the surface states are also observed to tail on the very strong main valence band emission (for example, the white region of intensity distribution in Fig. 3d). In the case of Fig. 2e (photon energy of 24 eV), the bulk VBM locates outside the first surface BZ. The surface state inside the first surface BZ is relatively better isolated from the bulk bands as compared with the one outside the first surface BZ. We thus study the dispersion along cut 2 (Fig. 3d), which only cuts across the surface states inside the first surface BZ. Both the dispersion maps and the momentum distribution curves in cut 2 reveal that the surface states along cut 2 are nearly Dirac-like (linearly dispersive) close to the Fermi level. In many TIs, the surface states deviate from ideal linearity24. Fitting of the momentum distribution curves of cut 2 (see Supplementary Fig. S6 for data analysis) shows that the experimental chemical potential (EF) lies roughly at (or just below) the Dirac point energy (ED), EF=ED±0.02 eV. The surface states' velocity is obtained to be 2.8±0.1 eV Å (4.2±0.2 × 105 m s−1) along cut 2, and 1.1±0.3 eV Å (1.7±0.4 × 105 m s−1) for the two outer branches along cut 1, respectively.

(a) First-principles calculated surface states of SnTe with energy set at 0.02 eV below the Dirac node energy are shown in red. The blue dotted lines mark the first surface BZ. (b) Left panel: ARPES iso-energetic contour mapping (EB=0.02 eV) of Pb0.6Sn0.4Te covering the first surface BZ using incident photon energy of 24 eV (throughout Fig. 3). Right panel: spectral intensity distribution as a function of momentum along the horizontal mirror line (defined by ky=0). The white arrows indicate the ARPES intensity peaks along this horizontal mirror line. (c) High-resolution Fermi surface mapping (EB=0.0 eV) in the vicinity of one of the  points (indicated by the white square in b). (d–f) Dispersion maps (EB vs k) and corresponding energy (momentum) distribution curves of the momentum space, cuts 1, 2 and 3. The momentum space cut-directions of cuts 1, 2 and 3 are defined by blue dotted lines in c. The second derivative image (SDI) of the measured dispersion is additionally shown for d.

points (indicated by the white square in b). (d–f) Dispersion maps (EB vs k) and corresponding energy (momentum) distribution curves of the momentum space, cuts 1, 2 and 3. The momentum space cut-directions of cuts 1, 2 and 3 are defined by blue dotted lines in c. The second derivative image (SDI) of the measured dispersion is additionally shown for d.

Spin polarization measurements of the surface states

We study the spin polarization of the low-energy states of the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te samples, which are highly dominated by the surface states near the Fermi level. We further compare and contrast their spin behaviour with that of the states at high binding energies away from the Fermi level, which are highly dominated by the bulk valence band in the same sample. Spin-resolved (SR) measurements are performed in the spin-resolved momentum distribution curve mode25,26, which measures the spin-resolved intensity and net spin polarization at a fixed binding energy along a certain momentum space cut direction (detailed in the Methods section). As shown in Fig. 4a, our spin-resolved measurements are performed along the mirror line ( ) direction, as the electronic and spin structure along this direction is most critically relevant to the predicted TCI phase15. Considering that the natural Fermi level of our x=0.4 samples are very close to the Dirac point (which is spin degenerate), the spin polarization of the surface states are measured at 60 meV below the Fermi level to gain proper contrast, namely SR-Cut 1 in Fig. 4a. As shown in the net spin polarization measurement of SR-Cut 1 in Fig. 4c, in total four spins pointing in the (±) in-plane tangential direction are revealed for the surface states along the mirror line direction. This is well consistent with the observed two surface state cones (four branches in total) near an

) direction, as the electronic and spin structure along this direction is most critically relevant to the predicted TCI phase15. Considering that the natural Fermi level of our x=0.4 samples are very close to the Dirac point (which is spin degenerate), the spin polarization of the surface states are measured at 60 meV below the Fermi level to gain proper contrast, namely SR-Cut 1 in Fig. 4a. As shown in the net spin polarization measurement of SR-Cut 1 in Fig. 4c, in total four spins pointing in the (±) in-plane tangential direction are revealed for the surface states along the mirror line direction. This is well consistent with the observed two surface state cones (four branches in total) near an  point along the mirror line direction. To compare and contrast the spin polarization behaviour of the surface states (SR-Cut 1) with that of the bulk states, we perform spin-resolved measurement SR-Cut 2 at EB=0.70 eV, where the bulk valence bands are prominently dominated. Indeed, in contrast to SR-Cut 1 reflecting the surface states’ spin polarization, no significant net spin polarization is observed for SR-Cut2, which is expected for the bulk valence bands of the inversion symmetric (centrosymmetric) Pb1−xSnxTe system. Our observed spin polarization configuration of the surface states is also in qualitative agreement with the first-principles calculation spin texture of the SnTe TCI surface states (see Supplementary Figs S7–S9 for texture calculation); and experimental derived topological invariant (Mirror Chern number27,28) nM=−2 also agrees with theoretical prediction for SnTe15.

point along the mirror line direction. To compare and contrast the spin polarization behaviour of the surface states (SR-Cut 1) with that of the bulk states, we perform spin-resolved measurement SR-Cut 2 at EB=0.70 eV, where the bulk valence bands are prominently dominated. Indeed, in contrast to SR-Cut 1 reflecting the surface states’ spin polarization, no significant net spin polarization is observed for SR-Cut2, which is expected for the bulk valence bands of the inversion symmetric (centrosymmetric) Pb1−xSnxTe system. Our observed spin polarization configuration of the surface states is also in qualitative agreement with the first-principles calculation spin texture of the SnTe TCI surface states (see Supplementary Figs S7–S9 for texture calculation); and experimental derived topological invariant (Mirror Chern number27,28) nM=−2 also agrees with theoretical prediction for SnTe15.

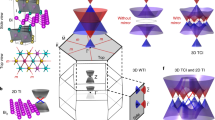

(a) ARPES dispersion map along the mirror line direction. The white dotted lines show the binding energies chosen for spin-resolved measurements, namely SR-Cut 1 at EB=0.06 eV and SR-Cut 2 at EB=0.70 eV. Inset: Measured spin polarization profile is shown by the green and blue arrows on top of the ARPES iso-energetic contour at binding energy EB=0.06 eV for SR-Cut1. Measured in-plane spin-resolved intensity (b) and in-plane spin polarization (c) of the surface states (SR-Cut 1) near the Fermi level at EB=0.06 eV. Measured in-plane spin-resolved intensity (d) and in-plane spin polarization (e) of the bulk valence bands (SR-Cut 2) at EB=0.70 eV. (f) Out-of-plane spin polarization measurements of SR-Cut 1 and SR-Cut 2. The error bar is ±0.01 for data points in all spin polarization measurements. (g) Theoretically expected spin polarization configuration of the surface states which corresponds to a mirror topological invariant (the mirror Chern number) nM=−2 (refs 27,28). Measured spin polarization texture configuration (green and blue arrows) of the surface states (SR-Cut 1) is shown on top of the calculated surface states. The blue and red lines are the calculated bulk bands and surface states, respectively.

Discussion

We discuss the possibility that the observed surface states in our data are the signature of the theoretically predicted TCI phase. The TCI phase was predicted to be observed in the band inverted side and absent in the non-inverted side15. In our data of the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te samples, which lie on the inverted side, surface states are observed, and only observed, along the two independent mirror line ( ) directions. Within the first surface BZ, two surface states are observed on each mirror line, which are found to locate in vicinity of the

) directions. Within the first surface BZ, two surface states are observed on each mirror line, which are found to locate in vicinity of the  points. Dispersion measurements (for example, Cut 2 in Fig. 3) reveal a nearly linear dispersion. Spin polarization measurements show that these surface states are spin-polarized and their spin polarization direction is locked with their momentum (spin–momentum locking). The overall electronic structure observed for our surface states are in qualitative agreement with the theoretically predicted surface states of the TCI phase in SnTe15. It is important to note that in an alloy, the space group symmetry is only of the averaged type. The spatial mirror symmetry required for the topological protection is only preserved in a globally averaged sense. To this date, it is not even theoretically known whether only averaged mirror symmetry is sufficient for the predicted TCI phase. In the absence of any theoretical work for the alloy, the experimental proof of mirror protection in the alloy Pb1−xSnxTe(Se) system perhaps requires the observation of strictly gapless surface states. The current ARPES works29,30 have not demonstrated resolution better than 5 meV, and thus fitting of the energy–momentum distribution curves lacks the resolving power to exclude gap values <5 meV (see Supplementary Fig. S10 and Supplementary Discussion). On the other hand, a proof of strictly gapless surface states in fact requires a surface- and spin-sensitive experimental setup with energy resolution better than 1 meV, which can even exclude possible small gap values of ≤1 meV at the Dirac point. Even a gap size of even <1 meV can lead to observable change in spin-transport experiments, thus destroying the delicate TCI phase. Therefore, although the existence of surface states correlated with band inversion transition is established here in our work, their gapped or gaplessness nature requires surface transport experiments on samples with improved quality, which is currently not possible29.

points. Dispersion measurements (for example, Cut 2 in Fig. 3) reveal a nearly linear dispersion. Spin polarization measurements show that these surface states are spin-polarized and their spin polarization direction is locked with their momentum (spin–momentum locking). The overall electronic structure observed for our surface states are in qualitative agreement with the theoretically predicted surface states of the TCI phase in SnTe15. It is important to note that in an alloy, the space group symmetry is only of the averaged type. The spatial mirror symmetry required for the topological protection is only preserved in a globally averaged sense. To this date, it is not even theoretically known whether only averaged mirror symmetry is sufficient for the predicted TCI phase. In the absence of any theoretical work for the alloy, the experimental proof of mirror protection in the alloy Pb1−xSnxTe(Se) system perhaps requires the observation of strictly gapless surface states. The current ARPES works29,30 have not demonstrated resolution better than 5 meV, and thus fitting of the energy–momentum distribution curves lacks the resolving power to exclude gap values <5 meV (see Supplementary Fig. S10 and Supplementary Discussion). On the other hand, a proof of strictly gapless surface states in fact requires a surface- and spin-sensitive experimental setup with energy resolution better than 1 meV, which can even exclude possible small gap values of ≤1 meV at the Dirac point. Even a gap size of even <1 meV can lead to observable change in spin-transport experiments, thus destroying the delicate TCI phase. Therefore, although the existence of surface states correlated with band inversion transition is established here in our work, their gapped or gaplessness nature requires surface transport experiments on samples with improved quality, which is currently not possible29.

Our observations of spin–momentum locked surface states in the inverted composition and their absence in the non-inverted composition suggest that Pb1−xSnxTe system is a tunable spin–orbit insulator analogous to the BiTl(S1−δSeδ)2 system5, which features a topological phase transition across the band inversion transition. However, the key difference is that odd number of band inversions in the BiTl(S1−δSeδ)2 system leads to odd number of surface states, whereas even number of band inversions in Pb1−xSnxTe system leads to even number of surface states per surface BZ. We further present a comparison of the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te and a single Dirac cone Z2 TI GeBi2Te431,32,33. As shown in Figs 5a–c, for GeBi2Te4, a single surface Dirac cone is observed enclosing the time-reversal invariant (Kramers’) momentum  in both ARPES and calculation results, demonstrating its Z2 TI state and the time-reversal symmetry protection of its single Dirac cone surface states. On the other hand, for the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te samples (Figs 5d–f), none of the surface states is observed to enclose any of the time-reversal invariant momentum, suggesting their irrelevance to the time-reversal symmetry-related protection. With future ultra-high-resolution experimental studies to prove the strict gapless nature of the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te surface states and therefore the topological protection by the crystalline mirror symmetries, it is then possible to realize magnetic yet topologically protected surface states in the Pb1−xSnxTe system due to its irrelevance to the time-reversal symmetry-related protection, which is fundamentally not possible in the Z2 TI systems. Considering the wide applications of magnetic materials in modern electronics, such topologically protected surface states compatible with magnetism will be of great interest in terms of integrating TI materials into future electronic devices.

in both ARPES and calculation results, demonstrating its Z2 TI state and the time-reversal symmetry protection of its single Dirac cone surface states. On the other hand, for the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te samples (Figs 5d–f), none of the surface states is observed to enclose any of the time-reversal invariant momentum, suggesting their irrelevance to the time-reversal symmetry-related protection. With future ultra-high-resolution experimental studies to prove the strict gapless nature of the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te surface states and therefore the topological protection by the crystalline mirror symmetries, it is then possible to realize magnetic yet topologically protected surface states in the Pb1−xSnxTe system due to its irrelevance to the time-reversal symmetry-related protection, which is fundamentally not possible in the Z2 TI systems. Considering the wide applications of magnetic materials in modern electronics, such topologically protected surface states compatible with magnetism will be of great interest in terms of integrating TI materials into future electronic devices.

(a) ARPES and calculation results of the surface states of a Z2 TI GeBi2Te4, an analogue to Bi2Se34. Left: ARPES measured Fermi surface with the chemical potential tuned near the surface Dirac point. Middle: first-principles calculated iso-energetic contour of the surface states near the Dirac point. Right: a stack of ARPES iso-energetic contours near the  point of the surface BZ. (b) ARPES measurements on the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te (x=0.4) samples and band calculation results on the end compound SnTe. The green straight lines in both a and b represent the linear energy–momentum dispersion of the Dirac cones. The green circles in b represent the double Dirac cone contours near each

point of the surface BZ. (b) ARPES measurements on the Pb0.6Sn0.4Te (x=0.4) samples and band calculation results on the end compound SnTe. The green straight lines in both a and b represent the linear energy–momentum dispersion of the Dirac cones. The green circles in b represent the double Dirac cone contours near each  point on the surface of Pb0.6Sn0.4Te.

point on the surface of Pb0.6Sn0.4Te.

We note that one advantage of the Pb1−xSnxTe system is that it can be easily doped with manganese, thallium, or indium to achieve bulk magnetic or superconducting states34,35,36. The symmetry in the Pb1−xSnxTe system (its nonmagnetic character) can be broken by magnetic or superconducting doping into the bulk or the surface. In future experiments, it would be interesting to explore the modification of our observed surface states brought out by magnetic and superconducting correlations, to search for exotic magnetic and superconducting orders on the surface. Such magnetic and superconducting orders on the surface states in Pb1−xSnxTe can be different from those recently observed in the Z2 TIs37,38 because of its very distinct topology of surface electronic structure. The novel magnetic and superconducting states to be realized with this novel topology are not strongly related to the question of gapless or gapped nature of the TCI phase. Therefore, our observation of the spin-polarized surface states presented here provides the much desired platform for realizing unusual surface magnetic and superconducting states in future experiments.

Methods

Electronic structure measurements

Spin-integrated ARPES measurements were performed with incident photon energies of 8–30 eV at beamline 5–4 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) in the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and with 28–90 eV photon energies at beamlines 4.0.3, 10.0.1 and 12.0.1 at the Advanced Light Source (ALS) in the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). Samples were cleaved in situ between 10 and 20 K at chamber pressure better than 5 × 10−11 torr at both the SSRL and the ALS, resulting in shiny surfaces. Energy resolution was better than 15 meV and momentum resolution was better than 1% of the surface BZ. To cross-check the cleavage surface orientation in ARPES measurements, the Laue back-reflection X-ray measurements were performed at the ALS using a Realtime Laue delay-line detector from the Multiwire Laboratories (Ithaca, NY), and diffraction spot indexing was performed using the MWL NorthStar orientation package. The X-ray Laue measurements along with the analysis results are presented in the Supplementary Fig. S11.

SD measurements

SR ARPES measurements were performed on the SIS beamline at the Swiss Light Source using the COPHEE spectrometer with two 40 kV classical Mott detectors and a photon energy of 24 eV, which systematically measures all three components of the spin of the electron (Px, Py and Pz) as a function of its energy and momentum25,26. Energy resolution was bettern than 60 meV and momentum resolution was better than 3% of the surface BZ for the spin-resolved measurements. Samples were cleaved in situ at 20 K at a chamber pressure <2 × 10−10 torr. Typical electron counts on the detector reach 5 × 105, which places an error bar of approximately ±0.01 for each point on our measured polarization curves.

Sample growth

Single crystals of Pb1−xSnxTe were grown by the standard growth method (described in ref. 39 for the end compound PbTe). High purity (99.9999%) elements of lead, tin and tellurium were mixed in the right ratio. Lead was etched by CH3COOH+H2O2 (4:1) to remove the surface oxide layer before mixing. The mixture was heated in a clean evacuated quartz tube to 924 °C, where it was held for two days. Afterwards, it was cooled slowly, at a rate of 1.5 °C h−1 in the vicinity of the melting point, from the high temperature zone towards room temperature. The nominal concentrations were estimated by the Pb/Sn mixture weight ratio before the growth, in which the two representative compositions presented in the paper were estimated to be xnom=0.20 and xnom=0.36. The concentration values were re-examined on the single crystal samples after growth using high-resolution X-ray diffraction measurements by tracking the change of the diffraction angle (the 2θ angle) of the sharpest Bragg peak, from which we obtained x=0.22 and x=0.39 (see Supplementary Fig. S12 for diffraction data). In the paper we note the chemical compositions as Pb0.8Sn0.2Te and Pb0.6Sn0.4Te.

First-principles calculation methods

We perform first-principles calculations to extract both the electronic structure and the spin texture of the SnTe surface states. Our first-principles calculations are within the framework of the density functional theory using full-potential projected augmented wave method40, as implemented in the VASP package41. The generalized gradient approximation42 is used to model exchange-correlation effects. The spin–orbital coupling is included in the self-consistent cycles. The surfaces are modelled by periodically repeated slabs of 33-atomic-layer thickness, separated by 13-Å wide vacuum regions, using a 12 × 12 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k point mesh over the BZ with 208 eV cutoff energy. The room temperature crystal structures of SnTe in ideal sodium chloride are used to construct the slab to have the required crystal structure and mirror symmetries required for the predicted TCI phase15 (the rhombohedral distortion is found to only occur in the Sn-rich compositions (x>0.5) and only at low temperature16). The experimental lattice constants of SnTe with the value of 6.327 Å are used43. The experimental lattice constant of PbTe with the value of 6.46 Å43 in ideal sodium chloride lattice are used in the PbTe band structure calculation.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Xu, S.-Y. et al. Observation of a TCI phase and topological phase transition in Pb1−xSnxTe. Nat. Commun. 3:1192 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2191 (2012).

Change history

04 August 2016

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Hasan M. Z., Moore J. E. Three-dimensional topological insulators. Ann. Rev. Cond. Mat. Phys. 2, 55–78 (2011).

Hasan M. Z., Kane C. L. Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi X.-L., Zhang S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Xia Y. et al. Observation of a large-gap topological-insulator class with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nat. Phys. 5, 398–402 (2009).

Xu S.-Y. et al. Topological phase transition and texture inversion in a tunable topological insulator. Science 332, 560–564 (2011).

Zogg H., Fach A., Masek J., Blunier S. Photovoltaic lead-chalcogenide on silicon infrared sensor arrays. Opt. Eng. 33, 1440–1449 (1994).

Zhu P. W. et al. Thermoelectric properties of PbTe prepared at high pressure and high temperature. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 11185–11188 (2002).

Dimmock J. O., Wright G. B. Band edge structure of PbS, PbSe, and PbTe. Phys. Rev. 135, 821–830 (1964).

Dimmock J. O., Melngailis I., Strauss A. J. Band structure and laser action in PbxSn1−xTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 16, 1193–1196 (1966).

Gao X., Daw M. S. Investigation of band inversion in (Pb,Sn)Te alloys using ab initio calculations. Phy. Rev. B 77, 033103 (2008).

Pankratov O. A., Pakhomov S. V., Volkov B. A. Supersymmetry in heterojunctions: band-inverting contact on the basis of Pb1−xSnxTe and Hg1−xCdxTe. Solid State Commun. 61, 93–96 (1987).

Volkov B. A., Pankratov O. A. Two-dimensional massless electrons in an inverted contact. JETP Lett. 42, 178–181 (1985).

Fradkin E., Dagotto E., Boyanovsky D. Physical realization of the parity anomaly in condensed matter physics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2967–2970 (1986).

Fu L. Topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 106802 (2011).

Hsieh H. et al. Topological crystalline insulators in the SnTe material class. Nat. Comm. 3, 982 (2012).

Iizumi M. et al. Phase transition in SnTe with low carrier concentration. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 38, 443–449 (1975).

Burke J. R. Jr, Allgaier R. S., Houston B. B. Jr, Babiskin J., Siebenmann P. G. Shubnikov-de Haas effect in SnTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 14, 360–361 (1965).

Littlewood P. B. et al. Band structure of SnTe studied by photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 086404 (2010).

Takafuji Y., Narita S. Shubnikov-de Haas measurements in N-Type Pb1−xSnxTe. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 21, 1315–1322 (1982).

Yannopapas V. Gapless surface states in a lattice of coupled cavities: a photonic analog of topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. B 84, 195126 (2011).

Hao N., Zhang P., Wang Y. Topological phases and fractional excitations of the exciton condensate in a special class of bilayer systems. Phys. Rev. B 84, 155447 (2011).

Vildanov N. M. Effective field theory description of topological crystalline insulators. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1205.3560 (2012).

Hsieh D. et al. A topological Dirac insulator in a quantum spin Hall phase. Nature 452, 970–974 (2008).

Fu L. Hexagonal warping effects in the surface states of the topological insulator Bi2Te3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 266801 (2009).

Hoesch M. et al. Spin-polarized Fermi surface mapping. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 124, 263–279 (2002).

Dil J. H. et al. Spin and angle resolved photoemission on non-magnetic low-dimensional systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 403001 (2009).

Teo J. C. Y., Fu L., Kane C. L. Surface states and topological invariants in three-dimensional topological insulators: application to Bi1−xSbx . Phys. Rev. B 78, 045426 (2008).

Hsieh D. et al. Observation of unconventional quantum spin textures in topological insulators. Science 323, 919–922 (2009).

Dziawa P. et al. Topological crystalline insulator states in Pb1−xSnxSe. Nat. Mater (e-pub ahead of print 30 September 2012; doi:10.1038/nmat3449).

Xu S.-Y. et al. Observation of topological crystalline insulator phase in the lead tin chalcogenide Pb1−xSnxTe material class. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1206.2088 (2012).

Xu S.-Y. et al. Discovery of several large families of topological insulator classes with backscattering-suppressed spin-polarized single-Dirac-cone on the surface. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1007.5111 (2010).

Neupane M. et al. Topological surface states and Dirac point tuning in ternary topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235406 (2012).

Okamoto K. et al. Observation of a highly spin polarized topological surface state in GeBi2Te4 . Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1207.2088 (2012).

Story T. et al. Carrier-concentration-induced ferromagnetism in PbSnMnTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 777–779 (1986).

Nakayama K., Sato T., Takahashi T., Murakami H. Doping induced evolution of Fermi surface in low carrier superconductor Tl-doped PbTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 227004 (2008).

Sasaki S. et al. Odd-parity pairing and topological superconductivity in a strongly spin-orbit coupled semiconductor. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1208.0059 (2012).

Wray L. A. et al. Observation of topological order in a superconducting doped topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 6, 855–859 (2010).

Xu S.-Y. et al. Hedgehog spin texture and Berry's phase tuning in a magnetic topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 8, 616–622 (2012).

Nugraha K., Suto O., Itoh J., Nishizawa Y. Yokota, growth and electrical properties of PbTe bulk crystals grown by the Bridgman method under controlled tellurium or lead vapor pressure. J. Cryst. Gr. 165, 402–407 (1996).

Kresse G., Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse G., Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Bis R. F., Dixon J. R. Applicability of Vagard's law to the PbxSn1−xTe alloy system. J. Appl. Phys. 40, 1918–1921 (1969).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Fu and A. Vishwanath for theoretical discussions on TCI. The work at Princeton and Princeton-led synchrotron x-ray-based measurements and the related theory at Northeastern University are supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences, US Department of Energy (grants DE-FG-02-05ER46200, AC03-76SF00098 and DE-FG02-07ER46352). M.Z.H. acknowledges visiting-scientist support from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and additional support from the A. P. Sloan Foundation. The spin-resolved and spin-integrated photoemission measurements using synchrotron X-ray facilities are supported by the Advanced Light Source, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, and the Swiss Light Source, by the Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy and the Swiss National Science Foundation. Theoretical computations benefited from the allocation of supercomputer time at NERSC and Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center. Sample growth and characterization are partially supported by DMR-0819860, DMR-1006492 and by the National Science Council (NSC)-Taiwan under project number NSC100-2119-M-002-021. We gratefully acknowledge N. Lavdovsky for assistance with sample preparation. We also thank M. Hashimoto and S.-K. Mo for beamline assistance at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and the Advanced Light Source in Berkeley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-Y.X. and C.L. performed the experiments with assistance from N.A., M.N., D.Q., I.B., L.A.W. and M.Z.H. A.M., E.M., Q.G., R.S., F.C.C. and R.J.C. provided samples; G.L., B.S., J.H.D. and J.D.D. provided beamline assistance; Y.J.W., H.L. and A.B. carried out the theoretical calculations; M.Z.H. was responsible for the conception and the overall direction, planning and integration among different research units.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S12, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 4277 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, SY., Liu, C., Alidoust, N. et al. Observation of a topological crystalline insulator phase and topological phase transition in Pb1−xSnxTe. Nat Commun 3, 1192 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2191

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2191

This article is cited by

-

Axially lattice-matched wurtzite/rock-salt GaAs/Pb1−xSnxTe nanowires

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Controllable strain-driven topological phase transition and dominant surface-state transport in HfTe5

Nature Communications (2024)

-

High-pressure induced Weyl semimetal phase in 2D Tellurium

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Terahertz lattice and charge dynamics in ferroelectric semiconductor SnxPb1−xTe

npj Quantum Materials (2022)

-

Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.