Abstract

Anyons—particles carrying fractional statistics that interpolate between bosons and fermions—have been conjectured to exist in low-dimensional systems. In the context of the fractional quantum Hall effect, quasi-particles made of electrons take the role of anyons whose statistical exchange phase is fixed by the filling factor. Here we propose an experimental setup to create anyons in one-dimensional lattices with fully tuneable exchange statistics. In our setup, anyons are created by bosons with occupation-dependent hopping amplitudes, which can be realized by assisted Raman tunnelling. The statistical angle can thus be controlled in situ by modifying the relative phase of external driving fields. This opens the fascinating possibility of smoothly transmuting bosons via anyons into fermions and of inducing a phase transition by the mere control of the particle statistics as a free parameter. In particular, we demonstrate how to induce a quantum phase transition from a superfluid into an exotic Mott-like state where the particle distribution exhibits plateaus at fractional densities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Usually, every particle in quantum theory is classified as either a boson—a particle joining any number of identical particles in a single-quantum state—or a fermion, characterized by the sole occupancy of its state. The exchange of two fermions leads due to the Pauli principle to a phase factor −1 in the total wavefunction, whereas the wavefunction of two bosons remains invariant under particle exchange. More than 30 years ago, researchers proposed a third fundamental category of particles living in two-dimensional systems, 'anyons'1,2,3,4,5. For two anyons, the wavefunction acquires a fractional phase eiθ under particle exchange, giving rise to fractional statistics, with 0<θ<π. For a few years, the physics of anyons remained restricted to the two-dimensional world6, until Haldane presented the concept of fractional statistics in arbitrary dimensions7.

Anyons in one-dimension (1D) are still unexplored to a wide extent. Recently, it has been put forward to create fractional statistics in a 1D Hubbard model of fermions with correlated hopping processes8. Anyons are realized in this case as low-energy elementary excitations.

Here, we introduce an exact mapping between anyons and bosons in 1D. We show that a Hubbard model of anyons is equivalent to a variant of the Bose–Hubbard model9 in which the bosonic hopping amplitudes are state-dependent. This conditional-hopping phase factor breaks reflection parity in the system, which is an important ingredient to realize fractional statistics10. We propose to realize bosons with conditional-hopping amplitudes using assisted Raman tunnelling in an optical lattice (OL)11,12. We discuss how the direct control of the statistical phase can induce a quantum phase transition from a bosonic superfluid into a Mott-like state, exhibiting exotic Mott shells at fractional densities. The 'statistical ramp' transmutes bosons smoothly into 'pseudofermions', with anyons as intermediate steps.

Anyons in 1D are defined13,14 by the generalized commutation relations

where the operators aj†, aj create or annihilate an anyon on site j. The sign function is such that sgn(j−k)=0 for j=k, hence, two particles on the same site behave as ordinary bosons. In consequence, anyons with statistics θ=π are pseudofermions: although being bosons on-site, they are fermions off-site.

Results

Mapping between anyons and bosons

We introduce an exact mapping between anyons and bosons in 1D. Let us define the fractional version of a Jordan–Wigner transformation,

with  the number operator for both particle types. Provided that the particles of type b are bosons,

the number operator for both particle types. Provided that the particles of type b are bosons,  and [bj, bi]=0 we can show that the mapped operators a indeed obey the anyonic commutation relations as introduced in equation (1). For a proof see Methods. This mapping elucidates that anyons in 1D are indeed non-local quasi-particles, made of bosons with an attached string operator.

and [bj, bi]=0 we can show that the mapped operators a indeed obey the anyonic commutation relations as introduced in equation (1). For a proof see Methods. This mapping elucidates that anyons in 1D are indeed non-local quasi-particles, made of bosons with an attached string operator.

Our ultimate goal is to propose a realistic setup for demonstrating an interacting gas of anyons in 1D OLs. We therefore introduce the Anyon–Hubbard model

where J is the tunnelling amplitude connecting two neighbouring sites and U is the on-site interaction energy. By inserting the Anyon–Boson mapping, equation (2), the Hamiltonian Ha can be rewritten in terms of bosonic operators:

The mapped, bosonic Hamiltonian thus describes bosons with a occupation-dependent amplitude  for hopping processes from right to left (j+1→j). If the target site j is unoccupied, the hopping amplitude is simply J. If it is occupied by one boson, the amplitude reads

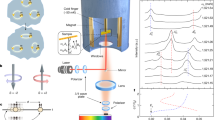

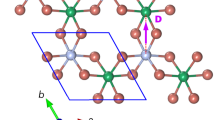

for hopping processes from right to left (j+1→j). If the target site j is unoccupied, the hopping amplitude is simply J. If it is occupied by one boson, the amplitude reads  , and so on. The conditional-hopping scheme is depicted in Figure 1a. We emphasize that the non-local mapping between anyons and bosons, equation (2), leads luckily to a purely local, and thus viable Hamiltonian.

, and so on. The conditional-hopping scheme is depicted in Figure 1a. We emphasize that the non-local mapping between anyons and bosons, equation (2), leads luckily to a purely local, and thus viable Hamiltonian.

(a) Anyons in 1D can be mapped onto bosons featuring occupation-dependent hopping amplitudes. (b) Assisted Raman tunnelling can selectively address hopping processes connecting different occupational states and induce a relative phase, realizing a fully tuneable particle exchange statistics angle θ. Energies are not in scale.

As expected from anyons, the reflection parity symmetry is broken10 at the level of the commutation relations, equation (1). The fractional Jordan–Wigner transformation, equation (2), transfers this asymmetry also to the bosonic case: The resulting Hamiltonian, equation (4), features a phase factor acting only on the left site j and thus violates parity. Even in the absence of the on-site interaction, U=0, the exponential operator in equation (4) gives rise to many-body interactions, as expected for anyons10.

In the limit U/J→∞, bosons are impenetrable and each site contains at most one particle. In this case, the phase factor disappears and the bosonic Hamiltonian Hb reduces to an ordinary Tonks–Girardeau gas15,16,17,18. However, we consider local occupation numbers beyond the hard-core limit, nj>1. Thus, anyons can exchange positions, changing the phase of the total wavefunction, and show non-trivial features.

Experimental realization

In our experimental proposal, the key point for realizing anyonic statistics is to induce a hopping term with a phase shift, which depends on the occupation of the left-hand site j, Figure 1b displays the basic concept. To distinguish between different local occupational states, we require a non-zero on-site interaction U. For simplicity, let us consider lattice site occupations that are restricted to nj=0, 1, 2 (higher local truncations are also possible; Methods). The occupation-dependent tunnelling and thus the conditional-hopping model equation (4) can be implemented in OLs with present experimental techniques. We propose to employ an assisted tunnelling scheme, based on ideas by Jaksch and Zoller19 and Juzeliunas et al.20. The OL is tilted, with an energy offset Δ between neighbouring sites, this additional field gradient breaks reflection parity. Two different occupational states (note that the occupational state nj=0 is not relevant) in either of the two sites form in total a four-dimensional atomic ground state manifold, which we propose to couple to an excited state |e〉 via four external driving fields (labelled 1, 2, 3 and 4 in Fig. 1b). According to this notation, singly and doubly occupied states are coupled by fields 2 and 1 in the left site and by 3 and 4 in the right site, respectively. The excited state can be experimentally realized in at least two alternative ways.

First, two spin-dependent lattices21,22,23 can be used. In the case of Rb87, one lattice for example traps atoms in the F=1, mF=−1 hyperfine state, assigned to the ground state manifold. The excited state |e〉 can then be engineered as a vibrational state of a second lattice, trapping atoms in the F=1, mF=0 hyperfine state. Atoms in the excited state would then be localized between the left and right wells of the F=1, mF=−1 lattice, but not necessarily in their centre.

This implementation would offer the advantage of external driving fields in the radio-frequency regime. Such frequencies could then still resolve22 the typical energies U and Δ (both of the order of a few kHz), which is necessary to selectively couple to the four different states in the ground state manifold.

Second, one can use two optical lattices, and trap ground state manifold atoms in the red-detuned lattice, while the excited state would live in the blue-detuned one. The driving fields necessary in this case would be then, however, typically in the THz frequency range, making a precise resolution of U and Δ more challenging for the experimentalist: in principle, a laser with a linewidth δlinewidth≪U, Δ would be needed.

The effective tunnelling rates Jab (a∈{1, 2}, b∈{3, 4}) are calculated for four Λ-systems, laser frequencies ωi, and Rabi frequencies Ωi (i∈{1, 2, 3, 4}) via adiabatic elimination, see Methods. We emphasize that the tilt energy Δ disappears in the effective Hamiltonian after rotating out time-dependent phase factors: indeed this energy offset is absorbed (or released) by the external radiation field, yielding a total Hamiltonian without a tilt term (see also Jaksch and Zoller19 on this issue).

The following conditions on the effective tunnelling rates Jab have to be satisfied in order to realize our model in equation (4):

where θ is the anyonic exchange phase. For a more detailed consideration of realistic energy scales and appropriate parameter regimes, see Methods.

Density in quasi-momentum space

We have computed the ground state wave function for the conditional-hopping Bose–Hubbard model, equation (4), using the Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG)24,25. In Figure 2, we plot the quasi-momentum distribution

as a function of the statistical phase angle θ. The case θ=0 corresponds to ordinary bosons, which for the parameters chosen quasi-condense. The density distribution in quasi-momentum space, equation (7), is thus peaked at k=0. Increasing θ to non-zero values, we find that the position of the peaks θmax(k) is shifted as a nonlinear function of k. Indeed, for fillings N/L>1 one finds a quadratic behaviour θmax(k)=α(k−k0)2+β. For fillings close to N/L=1, β→π, k0→π and α→−1/π. For higher fillings N/L→2, these fitting parameters are altered, however, the characteristic quadratic dependence is conserved.

The shift of the density peaks with increasing θ displays a characteristic quadratic behaviour. The fit to the trace of density maxima is depicted in white and yields fitting parameters k0=0.9828π, α=−1.0511/π, β=0.9982π. The inset displays the decrease of the peak occupations with θ (yellow circles) and indicates the statistically induced phase transition from a superfluid to a Mott-like state. Parameters: L=30, N=31, U/J=0.2.

In this analysis, we find two important characteristics of conditional-hopping bosons and thus anyons in 1D. The quadratic dependence of θmax on k contrasts ordinary magnetic fields (with a constant phase factor eiθ in the kinetic Hamiltonian). In this case, the shift of the peaks depends linearly on the phase angle θ. In the anyonic case, however, the growth of correlations with increasing θ may induce the characteristic quadratic trace, which could be directly observed in OL experiments using standard time-of-flight imaging.

An even more important observation is that the contrast of the peaks (and the phase coherence) decays with increasing θ. The peak values 〈nk(θ=θmax)〉 are plotted in the inset of Figure 2, in the pseudofermionic limit (θ→π) the peak is almost washed out. This suggests that an increase of θ transforms the initial quasi-condensate into a quantum state where all phase coherence is lost. It will become evident in the subsequent paragraphs that this quantum state will turn out to be a Mott-like state, with Mott plateaus emerging at fractional densities. We emphasize that this quantum phase transition is only driven by the statistical angle θ, all other parameters such as J/U are fixed. The loss of coherence can be understood as follows. With increasing θ the occupation-dependent phase factor in equation (4) becomes more and more important: hopping processes connecting sites with different occupations will contribute different phases and will cancel out in the kinetic Hamiltonian due to incoherent superpositions. This destructive interference effect is amplified by an increasing θ and induces the localization of particles, yielding an insulating phase. We emphasize that the present analysis of the density distribution in momentum space refers to the bosonic particles only, 〈nk〉=〈bk†bk〉. Namely, Figure 2 represents what would be observed in the experiment. However, although the mapping in equation (2) establishes a 1–1 correspondence between the number operators in real space,  the density distributions in momentum space may differ significantly. In this sense, a study of

the density distributions in momentum space may differ significantly. In this sense, a study of  and the superfluid order parameter in the original anyonic model (3) would be very interesting, but it is beyond the scope of this paper. A study of density distributions in momentum and real space was recently presented for the particular case of hard-core anyons26.

and the superfluid order parameter in the original anyonic model (3) would be very interesting, but it is beyond the scope of this paper. A study of density distributions in momentum and real space was recently presented for the particular case of hard-core anyons26.

Phase diagram

Next, we present the phase diagram for conditional-hopping bosons in the (μ/U, J/U)-plane. Just as in the case of ordinary bosons (θ=0)—the celebrated phase diagram of the Bose–Hubbard model9—the anyonic version will display insulating and superfluid regions. However, we find that the size of the insulating regions (Mott lobes) grows with increasing statistical angle θ—a fact that will be central in our proposal to design phase transitions by tuning the particle statistics.

The phase diagram is calculated as follows. We start with a unit filling ground state |N=L〉 and compare the energies with the ground states of |N=L±1〉. This yields the gap energies ΔE±(L), corresponding to the energy required to add or subtract one particle, respectively. These gap energies were calculated using DMRG for system sizes L=15, 30, 60, 90 and 120. From the finite-size scaling, we extrapolate the infinite-size values ΔE±, which are plotted in Figure 3 in the (μ/U, J/U)-plane. Note that a Mott insulator is associated with a non-zero gap ɛ=ΔE+−ΔE−, while for the superfluid phase ɛ=0 in the thermodynamic limit. For the bosonic case θ=0, we recover the first Mott lobe as in the work by Kühner and Monien27. Turning on the statistical angle and transmuting the bosons into anyons, we observe an expansion of the Mott-like insulating phase in both dimensions μ/U and J/U. The phase transition points (J/U)crit (defined by the cusps of the Mott lobes) are plotted in the inset of Figure 3 as a function of θ. In the pseudofermion limit θ→π, the Mott-like phase seems to extend to very large values of J/U. In contrast, ordinary bosons would form a superfluid state in this parameter regime. The expansion of the Mott lobes with θ is also observed in mean-field (MF) calculations for our model, equation (4). The MF solution produces very interesting patterns for the transition lines, as shown in Figure 5. For details of this calculation, see Methods.

The Mott lobe (corresponding to 〈n〉=1) expands with increasing statistical angle θ in both directions in the (μ/U, J/U)-plane. This demonstrates the novel possibility to induce a quantum phase transition from the superfluid into the insulating, Mott-like phase, by simply changing the particle statistics. The energies ΔE± are symbolized by circles (crosses), respectively. The critical phase transition points (U/J)crit are shown on the inset, as a function of θ. In the extreme limit θ→π, (U/J)crit tends to zero, that is, pseudofermions seem to be always in the insulating phase.

We note that the phase diagrams for conditional-hopping bosons and for anyons are the same. Owing to the unitarity of the mapping (2), the two models (3) and (4) are isospectral, and thus feature the same energy gaps and phase diagrams.

Discussion

We envision the following procedure to demonstrate the first statistically induced phase transition: We fix the parameters at J/U=0.5, N/L=1 and μ≃0. We start with a phase detuning θ=0 between the external driving fields (Methods), and thus realize a superfluid bosonic gas as the ground state. The phase angle θ is now continuously increased, leading to anyonization of the gas and growth of the Mott-like phase. At a critical value θc the phase border will surpass the fixed point in parameter space, which will be then located inside the Mott phase. The critical angle can be estimated from the phase diagram to be in the range θc∈[π/2, 3π/4]. For laser detunings beyond this critical angle, θ>θc, the gas will be in an insulating Mott-like state. In this way, the variation of the particle statistics in our proposal directly realizes a novel superfluid-to-Mott quantum phase transition.

An intriguing aspect of the Mott-like state emerges when a harmonic trapping potential is added to the system,  This simulates the experimental conditions also to a more realistic extent. In a harmonic trap, ordinary Mott insulators form real-space density distributions 〈ni〉 that resemble 'wedding cakes'9. Because of the broken translational invariance (induced by the trap), the chemical potential in the local density approximation now is a function of the lattice sites. The distribution 〈ni〉 thus exhibits plateaus at integer densities, for ordinary bosons in a Mott-insulating state.

This simulates the experimental conditions also to a more realistic extent. In a harmonic trap, ordinary Mott insulators form real-space density distributions 〈ni〉 that resemble 'wedding cakes'9. Because of the broken translational invariance (induced by the trap), the chemical potential in the local density approximation now is a function of the lattice sites. The distribution 〈ni〉 thus exhibits plateaus at integer densities, for ordinary bosons in a Mott-insulating state.

We have computed the density distribution for a system with additional harmonic confinement, at the same fixed parameter point as in the procedure outlined above. The result is plotted in Figure 4. For low statistical phase angles θ (and thus a superfluid state), the density distribution displays a smooth, quadratic profile centred around the minimum of the trap. Beyond the critical phase angle, θ>θc, Mott-like plateaus appear in 〈ni〉. Surprisingly, in addition to the integer density Mott plateau at n=1, a new plateau emerges at the fractional value n≃½. Fractional Mott plateaus persist also in other parameter regimes, when J/U and the trapping potential V are varied, and seem to form a universal feature of 1D anyonic gases at large exchange phases θ, which will be subject of a future study.

The density distributions 〈ni〉 are plotted for increasing statistical angle θ. In each panel, the density distribution for ordinary bosons (θ=0, blue line) is drawn for reference. The distribution at high statistical angles ( , marked black and green) exhibit a Mott-like plateau at the fractional value n≃½ (marked by arrows). Parameters: N=L=30, J/U=0.5, V/U=0.01.

, marked black and green) exhibit a Mott-like plateau at the fractional value n≃½ (marked by arrows). Parameters: N=L=30, J/U=0.5, V/U=0.01.

Recent progress on the experimental side have made direct imaging of density distributions possible, using 'quantum gas microscopy'28,29. A few months ago, the plateau structure of the Mott insulator was directly observed for the first time30 at the single-atom level. This new technique opens up the possibility to directly demonstrate fractional Mott plateaus and to image statistically induced phase transitions in situ.

In summary, we have shown how to realize fractional statistics in 1D optical lattices, using bosons in a realistic experimental environment. The experiment we propose features the full control and tuneability of the particles' exchange statistics—paving the way to the first statistically induced quantum phase transition.

Methods

Realizing conditional-hopping bosons

In this section we discuss how to realize the conditional-hopping Hamiltonian equation (4), using four different and independent Λ-transitions31. In general, we assume a deep optical lattice potential, giving rise to a negligible bare kinetic tunnelling amplitude Jkin. Let us focus for a moment on one Λ-scheme, where two ground state levels |a〉 and |b〉 are coupled through a Raman process via an excited state |e〉. In our case, |a〉 and |b〉 correspond to the wavefunctions of atoms at distance d localized in neighbouring sites of the tilted lattice V(x) (d being the lattice constant), while |e〉 experiences another potential V′(x) (for a brief discussion of two realistic experimental possibilites to realize V′(x), see the main text). The levels have energies Ei=ℏωi, i=a, b, e and the transition between a(b) and e is driven by an external radiation field with frequency ωe−ωa(b)−δ, with detuning δ. Note that in our scheme the energies Ei depend on Δ and U. The Hamiltonian for the three-level Λ-system reads

where  Here, the quantity

Here, the quantity  is the Rabi frequency for the transition a(b)→e with the atom centred in the same position. However, as ground and excited states feel different lattices, the x components of the Wannier functions w(x) are slightly displaced. Thus, the off-diagonal elements in equation (8) contain the integrals19

is the Rabi frequency for the transition a(b)→e with the atom centred in the same position. However, as ground and excited states feel different lattices, the x components of the Wannier functions w(x) are slightly displaced. Thus, the off-diagonal elements in equation (8) contain the integrals19

where ka(b) is the x-component of the momentum of the driving radiation field, with modulus  is the atom position in the left well, while xe refers to the position in the excited state. Note that the integrals in equation (9) are in general non-zero, as the two Wannier functions belong to different lattices. The quantities γa(b) are complex numbers, whose modulus and phase can be freely tuned by choosing the appropriate intensity, polarization and direction of the driving fields. For sufficiently large detunings δ>|γa(b)|, the level |e〉 can be adiabatically eliminated and in the rotating wave approximation the effective Hamiltonian in the subspace {|a〉, |b〉} reads

is the atom position in the left well, while xe refers to the position in the excited state. Note that the integrals in equation (9) are in general non-zero, as the two Wannier functions belong to different lattices. The quantities γa(b) are complex numbers, whose modulus and phase can be freely tuned by choosing the appropriate intensity, polarization and direction of the driving fields. For sufficiently large detunings δ>|γa(b)|, the level |e〉 can be adiabatically eliminated and in the rotating wave approximation the effective Hamiltonian in the subspace {|a〉, |b〉} reads

where  is the non-rotating version of γ, that is, without the time-dependent phase factors. In order to realize equation (4), we suggest to employ four driving fields (Fig. 1b) with different frequencies in order to avoid interferences. This situation would correspond to a maximum of two atoms per site. If the local density truncation were set to a higher number, more external driving fields would become necessary. As all fields can be tuned independently from each other, this poses no problems besides potential budgetary considerations.

is the non-rotating version of γ, that is, without the time-dependent phase factors. In order to realize equation (4), we suggest to employ four driving fields (Fig. 1b) with different frequencies in order to avoid interferences. This situation would correspond to a maximum of two atoms per site. If the local density truncation were set to a higher number, more external driving fields would become necessary. As all fields can be tuned independently from each other, this poses no problems besides potential budgetary considerations.

The couplings J13, J14, J23 and J24, between the four different levels are then obtained in terms of the effective Rabi frequencies,

Our aim is to satisfy the conditions set in equations (5) and (6) in order to engineer a state-dependent phase factor. This implies  which can be achieved by the free tuneability of each driving fields's frequency, intensity, polarization and direction. Furthermore this choice of parameters implies

which can be achieved by the free tuneability of each driving fields's frequency, intensity, polarization and direction. Furthermore this choice of parameters implies  , that is, the diagonal elements of the effective Hamiltonian are now equivalent. Thus, the tilt energy Δ has vanished via adiabatic elimination, and consequently also does not appear in equation (4). Indeed, this offset energy between neighbouring sites is compensated by the external radiation field. As the assisted tunnelling proposed in this article is the only mechanism for hopping in the lattice, unwanted effects such as Bloch oscillations do not appear in our system (the bare kinetic tunnelling amplitude Jkin is assumed to be negligible compared with all energy scales discussed here).

, that is, the diagonal elements of the effective Hamiltonian are now equivalent. Thus, the tilt energy Δ has vanished via adiabatic elimination, and consequently also does not appear in equation (4). Indeed, this offset energy between neighbouring sites is compensated by the external radiation field. As the assisted tunnelling proposed in this article is the only mechanism for hopping in the lattice, unwanted effects such as Bloch oscillations do not appear in our system (the bare kinetic tunnelling amplitude Jkin is assumed to be negligible compared with all energy scales discussed here).

In summary, the parameters discussed here have to satisfy the following conditions.

First, δlinewidth≪Δ, U, so that the external driving fields resolve the different levels of the ground state manifold. Second, large detunings δ≫|γa(b)| are required for a short-lived excited state and the validity of the adiabatic elimination. Third, Δ and U can be in the same frequency regime (a few kHz), but should not be identical (their difference should be >>δlinewidth). As an example, Δ≃2 kHz, U≃3 kHz, |Jab|=J≃5 kHz and |γab|≃20 kHz would be sufficient if the linewidth of the radiation field were δlinewidth≃50 Hz, which is a realistic assumption for typical radio-frequency driving fields (see, for example, the works by Campbell et al.22 and McKay and DeMarco23).

Fractional Jordan–Wigner mapping

In the following we prove that anyons are isomorphic to bosons in 1D.

In particular, we prove that the operators a, as defined in the non-local mapping, equation (2), indeed obey the anyonic commutation relations of equation (1), provided that the particles of type b are bosons.

For the case i<j we wish to rewrite products of anyonic operators in terms of the bosonic ones:

Here we have defined f(θ)≡eiθsgn(i−j) and used that f(θ)=e−iθ, as i<j was assumed. We can now evaluate the left-hand side of equation (1):

Thus, the anyonic commutation relations have been proven for the case i<j. The proof for the case i>j is very similar. For the case i=j, one just has to note that  and f(θ)=1. Note that the resulting conditional-hopping bosonic Hamiltonian, equation (4), resembles the exactly solvable model of q-bosons32. However, this model is not equivalent to our model.

and f(θ)=1. Note that the resulting conditional-hopping bosonic Hamiltonian, equation (4), resembles the exactly solvable model of q-bosons32. However, this model is not equivalent to our model.

Mean-field calculation

The conditional-hopping bosonic Hamiltonian is given by equation (4). In addition, we now include also a chemical potential term. Expressing energies in units of U (we fix U≡1), we have

where for convenience we have defined

In absence of hopping J=0, all the sites are independent and the ground state is of the Gutzwiller type

where ν=N/L is the filling factor. The local energies are ɛν=½ν (ν−1)−μν, while the local gaps for adding or subtracting one boson are, respectively

So, the ground state in every site has ν particles in the interval  with

with  The gap in the whole system at a given number of particles is given by Δ=1, obtained by removing an atom at some site an putting it in another one already occupied.

The gap in the whole system at a given number of particles is given by Δ=1, obtained by removing an atom at some site an putting it in another one already occupied.

Here the MF is obtained by decoupling the hopping term as  where the order parameters are α1=〈bj〉 and α2=〈cj〉. Accordingly, the Hamiltonian (13) in MF becomes

where the order parameters are α1=〈bj〉 and α2=〈cj〉. Accordingly, the Hamiltonian (13) in MF becomes

with

The two parameters α1 and α2 are not completely independent as as they are both vanishing or non vanishing at the same time. Of course there is a trivial solution corresponding to αl=0, l=1, 2, which corresponds to the Mott-insulating phase. The occurrence of α≠0 signals the instability towards superfluid correlations. On inhomogeneous lattices, a further situation can in principle occur, where αl≠0 only on a fraction of the lattice sites. The self-consistent relation defines a map αl=Λll′αl′, obtained by linearizing about the solution αl=0. The instability of the trivial solution sets in when the maximal eigenvalue of Λ is >1. Close to the trivial point, it holds |αl|≪1, hence, the kinetic term can be treated perturbatively. Up to first perturbative order, the wavefunction can be written as |ψ〉=|ψ(0)〉+|ψ(1)〉, where |ψ(0)〉=|ν〉 and

Hence, using the self-consistency relations α1=〈ψ|bj|ψ〉 and α2=〈ψ|cj|ψ〉,

The matrix Λ is then

with

since every lobe is labelled by ν=[μ]+1. The eigenvalues of Λ are given by

The condition max{λ+,λ−}=1 signals the onset of instability of the trivial solution and hence establishes the critical coupling Jcrit along the Mott-superfluid transition line. In Figure 5, the phase diagrams for several values of θ are shown. The Mott lobes expand for non-zero statistical angles θ, a fact central for designing statistically induced phase transitions.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Keilmann, T. et al. Statistically induced phase transitions and anyons in 1D optical lattices. Nat. Commun. 2:361 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1353 (2011).

References

Leinaas, J. & Myrheim, J. On the theory of identical particles. Nuovo Cimento B 37, 1–23 (1977).

Goldin, G. A., Menikoff, R. & Sharp, D. H. Representations of a local current algebra in nonsimply connected space and the Aharonov-Bohm effect. J. Math. Phys. 22, 1664–1668 (1981).

Wilczek, F. Magnetic flux, angular momentum, and statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1144–1146 (1982).

Tsui, D. C., Stormer, H. L. & Gossard, A. C. Two-dimensional magnetotransport in the extreme quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1559–1562 (1982).

Laughlin, R. B. Anomalous quantum hall effect: an incompressible quantum fluid with fractionally charged excitations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 50, 1395–1398 (1983).

Canright, G. S. & Girvin, S. M. Fractional statistics: quantum possibilities in two dimensions. Science 247, 1197–1205 (1990).

Haldane, F. D. M. 'Fractional statistics' in arbitrary dimensions: a generalization of the Pauli principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 937–940 (1991).

Vitoriano, C. & Coutinho-Filho, M. D. Fractional statistics and quantum scaling properties of the hubbard chain with bond-charge interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 146404 (2009).

Fisher, M. P. A. et al. Boson localization and the superfluid-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B 40, 546–570 (1989).

Wilczek, F. Fractional Statistics And Anyon Superconductivity (World Scientific, Singapore, 1990).

Jaksch, D. et al. Cold bosonic atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3108–3111 (1998).

Greiner, M. et al. Quantum phase transition from a superfluid to a Mott insulator in a gas of ultracold atoms. Nature 415, 39–44 (2002).

Batchelor, M. T., Guan, X.- W. & Oelkers, N. One-dimensional interacting anyon gas: low-energy properties and haldane exclusion statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 210402 (2006).

Kundu, A. Exact solution of double-δ function bose gas through an interacting anyon gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1275–1278 (1999).

Kinoshita, T. et al. Observation of a one-dimensional tonks-girardeau gas. Science 305, 1125–1128 (2004).

Paredes, B. et al. Tonks-Girardeau gas of ultracold atoms in an optical lattice. Nature 429, 277–281 (2004).

Haller, E. et al. Realization of an excited, strongly correlated quantum gas phase. Science 325, 1224–1227 (2009).

Haller, E. et al. Pinning quantum phase transition for a Luttinger liquid of strongly interacting bosons. Nature 466, 597–600 (2010).

Jaksch, D. & Zoller, P. Creation of effective magnetic fields in optical lattices: the Hofstadter butterfly for cold neutral atoms. New J. Phys. 5, 56.1–56.11 (2003).

Juzeliunas, G. et al. Light induced effective magnetic fields for ultra-cold atoms in planar geometries. Phys. Rev. A 73, 025602 (2006).

Mandel, O. et al. Coherent transport of neutral atoms in spin-dependent optical lattice potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 010407 (2003).

Campbell, G. K. et al. Imaging the mott insulator shells by using atomic clock shifts. Science 313, 649–652 (2006).

McKay, D. & DeMarco, B. Thermometry with spin-dependent lattices. New J. Phys. 12, 055013 (2010).

White, S. R. & Noack, R. M. Real-space quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3487–3490 (1992).

Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 259–315 (2005).

Hao, Y. et al. Ground-state properties of hard-core anyons in one-dimensional optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 79, 043633 (2009).

Kühner, T. D. & Monien, H. Phases of the one-dimensional Bose-Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 58, R14741–R14744 (1998).

Bakr, W. et al. A quantum gas microscope for detecting single atoms in a Hubbard-regime optical lattice. Nature 462, 74–77 (2009).

Sherson, J. F. et al. Single-atom resolved fluorescence imaging of an atomic mott insulator. Nature 467, 68–72 (2010).

Bakr, W. et al. Probing the superfluid to mott insulator transition at the single atom level. Science 329, 547–50 (2010).

Scully, M. O. & Zubairy, M. S. Quantum Optics (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Bogoliubov, N. M. & Bullough, R. K. A q-deformed completely integrable bose gas model. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 25, 4057–4071 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ignacio Cirac, Stefan Trotzky, Ulrich Schollwöck and Maciej Lewenstein for helpful discussions. T.K. acknowledges funding from both LMU and Wellness Heaven.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The theory and the experimental proposal were conceived by T.K. and M.R. Numerical data analysis was performed by S.L. under supervision of T.K. The DMRG algorithm was provided by I.M. The manuscript was written by T.K. and M.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keilmann, T., Lanzmich, S., McCulloch, I. et al. Statistically induced phase transitions and anyons in 1D optical lattices. Nat Commun 2, 361 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1353

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1353

This article is cited by

-

Anyonic bound states in the continuum

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Strain and pseudo-magnetic fields in optical lattices from density-assisted tunneling

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Observation of Bloch oscillations dominated by effective anyonic particle statistics

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Realizing a 1D topological gauge theory in an optically dressed BEC

Nature (2022)

-

Tailoring quantum gases by Floquet engineering

Nature Physics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.