Abstract

There is a significant ongoing effort in realizing quantum annealing with different physical platforms. The challenge is to achieve a fully programmable quantum device featuring coherent adiabatic quantum dynamics. Here we show that combining the well-developed quantum simulation toolbox for Rydberg atoms with the recently proposed Lechner–Hauke–Zoller (LHZ) architecture allows one to build a prototype for a coherent adiabatic quantum computer with all-to-all Ising interactions and, therefore, a platform for quantum annealing. In LHZ an infinite-range spin-glass is mapped onto the low energy subspace of a spin-1/2 lattice gauge model with quasi-local four-body parity constraints. This spin model can be emulated in a natural way with Rubidium and Caesium atoms in a bipartite optical lattice involving laser-dressed Rydberg–Rydberg interactions, which are several orders of magnitude larger than the relevant decoherence rates. This makes the exploration of coherent quantum enhanced optimization protocols accessible with state-of-the-art atomic physics experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

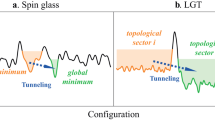

Quantum annealing is a quantum computing paradigm with the aim to solve generic optimization problems1,2,3,4, where the cost function corresponds to the energy of an infinite-range Ising spin glass5. Finding the optimal solution of the problem is thus equivalent to determining the ground state of the spin glass. In quantum annealing, this task is accomplished by adiabatic passage of a system of N spins in the instantaneous ground state of a Hamiltonian (denoted logical spin model) of the form

Here  are Pauli spin operators, and time-dependent scheduling functions

are Pauli spin operators, and time-dependent scheduling functions  and

and  deform

deform  from a trivial initial Hamiltonian with

from a trivial initial Hamiltonian with  and transverse local fields

and transverse local fields  , into the spin glass Hamiltonian with

, into the spin glass Hamiltonian with  , where the optimization problem is encoded in local fields

, where the optimization problem is encoded in local fields  and infinite–range interactions

and infinite–range interactions  5.

5.

Current quantum annealing implementations6 focus on the adiabatic preparation of classical states with thermally assisted adiabatic quantum protocols. Here, we propose a setup for coherent annealing with the aim to open an experimental route to adiabatic and non-adiabatic protocols. For example, non-adiabatic and fully coherent sweeps allow for counter-diabatic protocols7 with the potential to improve scaling laws in quantum annealing considerably, as well as the recently introduced hybrid annealing method8. While thermally assisted annealing is suitable to prepare classical ground states or mixtures, a fully coherent annealer can also be used to prepare quantum superpositions from Hamiltonians with degenerate ground states9. A coherent protocol with non-stoquastic10 driver terms opens a promising route to highly efficient protocols for optimization problems11.

A major challenge in implementing equation (1) is posed by the required individually programmable long–range interactions  , which is in contradiction to polynomially decaying interactions in cold atoms and molecule setups. Adopting the LHZ architecture12, the infinite-range spin glass is translated to a lattice spin model, where new physical spins

, which is in contradiction to polynomially decaying interactions in cold atoms and molecule setups. Adopting the LHZ architecture12, the infinite-range spin glass is translated to a lattice spin model, where new physical spins  represent the relative orientation of two logical spins

represent the relative orientation of two logical spins  of equation (1). If two logical spins are aligned in parallel, that is,

of equation (1). If two logical spins are aligned in parallel, that is,  or

or  , then the corresponding physical spin is in state

, then the corresponding physical spin is in state  , while if the logical spins are aligned anti-parallel, that is,

, while if the logical spins are aligned anti-parallel, that is,  or

or  , then the physical spin is in state

, then the physical spin is in state  . The major advantage of this approach is that the interaction energy of a pair of logical spins can now be implemented with a local field acting on a single physical spin.

. The major advantage of this approach is that the interaction energy of a pair of logical spins can now be implemented with a local field acting on a single physical spin.

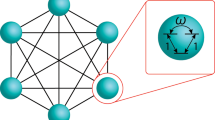

A general optimization problem in the LHZ architecture becomes

with new schedule functions At, Bt and Ct, and transverse fields ai. Physical spins are arranged on a square lattice (see blue spheres in Fig. 1), where the index i labels the entries of the matrix  . The number of physical spins K equals the number of connections in the original model, which is quadratically larger than in the original problem, for example, K=N(N−1)/2 for all-to-all connected graphs. This enlarged state space contains states, where collections of physical spins encode conflicting relative orientations of the logical spins. These states can be locally identified and energetically penalized by four-body constraints H□ at each plaquette □ of the square lattice, such that at the end of the sweep plaquettes either contain all an even12, or all an odd13 number of spins in the

. The number of physical spins K equals the number of connections in the original model, which is quadratically larger than in the original problem, for example, K=N(N−1)/2 for all-to-all connected graphs. This enlarged state space contains states, where collections of physical spins encode conflicting relative orientations of the logical spins. These states can be locally identified and energetically penalized by four-body constraints H□ at each plaquette □ of the square lattice, such that at the end of the sweep plaquettes either contain all an even12, or all an odd13 number of spins in the  state, thus realising an even or odd parity representation of equation (2). This ensures that the final ground state of the LHZ Hamiltonian (2) corresponds to the final ground state of the logical Hamiltonian (1), and thus to the optimal solution of the optimization problem. Importantly, the optimization problem is now encoded in local fields

state, thus realising an even or odd parity representation of equation (2). This ensures that the final ground state of the LHZ Hamiltonian (2) corresponds to the final ground state of the logical Hamiltonian (1), and thus to the optimal solution of the optimization problem. Importantly, the optimization problem is now encoded in local fields  , corresponding to single-particle energy shifts. We show that the above model for a programmable quantum annealer can be emulated in an atomic Rydberg setup, which builds on the remarkable recent advances towards realizing complex spin models with cold atoms in lattices interacting via designed Rydberg–Rydberg interactions14,15,16,17,18.

, corresponding to single-particle energy shifts. We show that the above model for a programmable quantum annealer can be emulated in an atomic Rydberg setup, which builds on the remarkable recent advances towards realizing complex spin models with cold atoms in lattices interacting via designed Rydberg–Rydberg interactions14,15,16,17,18.

(a) The cost function of a general optimization problem in the form of a spin glass with infinite-range interactions  is encoded in the Lechner–Hauke–Zoller (LHZ) architecture in local fields Ji. (b) Rubidium (blue) and Caesium (red) atoms are trapped in a square lattice geometry representing physical and ancilla spins, respectively, where the spin degree of freedom is encoded in two long-lived hyperfine states

is encoded in the Lechner–Hauke–Zoller (LHZ) architecture in local fields Ji. (b) Rubidium (blue) and Caesium (red) atoms are trapped in a square lattice geometry representing physical and ancilla spins, respectively, where the spin degree of freedom is encoded in two long-lived hyperfine states  and

and  , illustrated in insets (c,d). The programmable local fields Ji are induced by AC stark shifts from laser coupling the

, illustrated in insets (c,d). The programmable local fields Ji are induced by AC stark shifts from laser coupling the  state to low-lying 5P states using a digital mirror device (DMD). The four-body gauge constraints at each plaquette (for example, the black dotted square) are engineered using off-resonant laser coupling of the

state to low-lying 5P states using a digital mirror device (DMD). The four-body gauge constraints at each plaquette (for example, the black dotted square) are engineered using off-resonant laser coupling of the  states to Rydberg P-states

states to Rydberg P-states  ,

,  or

or  and require only uniform illumination of the system with ultraviolet laser light. Γ1, Γ2 and ΓC are the decay rates from the excited states.

and require only uniform illumination of the system with ultraviolet laser light. Γ1, Γ2 and ΓC are the decay rates from the excited states.

Results

Four-body parity constraints

The key challenge of implementing  is resolved with Rydberg atoms by combining the odd parity representation13 of equation (2) with enhanced Rydberg–Rydberg dressing19 schemes in a two-species mixture20,21. In the odd parity representation, the sum of the four spins at each plaquette is either 2 or −2. We introduce a single ancilla qubit

is resolved with Rydberg atoms by combining the odd parity representation13 of equation (2) with enhanced Rydberg–Rydberg dressing19 schemes in a two-species mixture20,21. In the odd parity representation, the sum of the four spins at each plaquette is either 2 or −2. We introduce a single ancilla qubit  at each plaquette, which can compensate the two associated energies and make odd parity plaquette states degenerate ground states of the constraint Hamiltonian

at each plaquette, which can compensate the two associated energies and make odd parity plaquette states degenerate ground states of the constraint Hamiltonian  , with stabilizer operators

, with stabilizer operators  , and energy gap

, and energy gap  . This allows to implement the four-body gauge constraints via appropriately designed two-body Ising interactions between physical and ancilla qubits.

. This allows to implement the four-body gauge constraints via appropriately designed two-body Ising interactions between physical and ancilla qubits.

Here we consider a more general and robust form of  , consisting of all combinations of two-body interactions along the edges and diagonals of the plaquette, as well as with the ancilla spin (see Fig. 2(a)), of the form

, consisting of all combinations of two-body interactions along the edges and diagonals of the plaquette, as well as with the ancilla spin (see Fig. 2(a)), of the form

(a) Four-body interactions between physical spins (blue) of the same plaquette are constructed from two-body interactions between physical spins of strength 1 along the edge of the plaquette (left), interactions of strength β along the diagonal (middle) and additional interactions of strength α between an ancilla qubit (red) located at the centre of each plaquette and the surrounding physical qubits (right). (b) Eigenenergies E□ of the Hamiltonian of equation (3), as a function of the physical spin-ancilla interaction strength α for a particular  . Odd parity eigenstates with the right (lower left inset) or wrong (upper right inset) ancilla orientation have an energy ±2α. The maximally polarized states with all four physical spins up or down (upper left inset) have energy

. Odd parity eigenstates with the right (lower left inset) or wrong (upper right inset) ancilla orientation have an energy ±2α. The maximally polarized states with all four physical spins up or down (upper left inset) have energy  , while the spin-ice states are independent of the ancilla interaction α and have constant energies −2β and −4+2β. The thick blue line indicates the window of interest where the odd parity states are the ground states of the plaquette Hamiltonian.

, while the spin-ice states are independent of the ancilla interaction α and have constant energies −2β and −4+2β. The thick blue line indicates the window of interest where the odd parity states are the ground states of the plaquette Hamiltonian.

where α and β are relative interaction strengths compared to spin interactions along the plaquette edge. The energy spectrum E□ of a single plaquette Hamiltonian is shown in Fig. 2(b), as a function of the parameters α and β. Importantly, there exists a parameter regime 0<2−β<α<2+β with 0<β<1, where the odd parity states are degenerate and have a lower energy than the even parity states. As the precise value of the gap in Fig. 2 is not relevant, as long as it exceeds all other energy scales,  is quite robust against small variations in interaction strengths, and the parameters α, β need not be fine-tuned.

is quite robust against small variations in interaction strengths, and the parameters α, β need not be fine-tuned.

Interaction design

In the Rydberg quantum annealer illustrated in Fig. 1, qubits are encoded in two long-lived hyperfine ground states  ,

,  of 87Rb and

of 87Rb and  ,

,  of 133Cs, representing physical and ancilla spins, respectively. These states are trapped in a deep optical or magnetic square lattice with unity filling and frozen motion22,23. Consecutive loading schemes of rubidium and caesium have been successfully demonstrated21, which could be combined with the recent remarkable progress in trapping atoms in almost arbitrary 2D geometries using optical tweezers22,23. Alternatively, it was suggested20 that rubidium and caesium atoms are trapped in the same optical lattice created by counter-propagating laser beams with wavelength λL≈820 nm. This particular wavelength is blue detuned for Cs atoms, which will be trapped at the intensity minima, but red detuned for Rb atoms, which will be trapped at the intensity maxima. Thus the atoms are trapped in an alternating pattern, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

of 133Cs, representing physical and ancilla spins, respectively. These states are trapped in a deep optical or magnetic square lattice with unity filling and frozen motion22,23. Consecutive loading schemes of rubidium and caesium have been successfully demonstrated21, which could be combined with the recent remarkable progress in trapping atoms in almost arbitrary 2D geometries using optical tweezers22,23. Alternatively, it was suggested20 that rubidium and caesium atoms are trapped in the same optical lattice created by counter-propagating laser beams with wavelength λL≈820 nm. This particular wavelength is blue detuned for Cs atoms, which will be trapped at the intensity minima, but red detuned for Rb atoms, which will be trapped at the intensity maxima. Thus the atoms are trapped in an alternating pattern, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

In particular, we choose the  and

and  hyperfine states of the 52S1/2 ground state manifold of 87Rb and the

hyperfine states of the 52S1/2 ground state manifold of 87Rb and the  and

and  hyperfine states of the 62S1/2 ground state manifold of 133Cs. The first term of equation (2) can be realized with a coherent driving field of amplitude ai coupling the

hyperfine states of the 62S1/2 ground state manifold of 133Cs. The first term of equation (2) can be realized with a coherent driving field of amplitude ai coupling the  and

and  states for both physical and ancilla atoms, written in a rotating frame. The second term is obtained using single-particle AC-Stark shifts from off-resonant laser coupling of the

states for both physical and ancilla atoms, written in a rotating frame. The second term is obtained using single-particle AC-Stark shifts from off-resonant laser coupling of the  spin state to low-lying

spin state to low-lying  states using a digital micro-mirror device24. The strenght of these fields can be easily varied as a function of time, thus implementing the sweep coefficients At and Bt in equation (2).

states using a digital micro-mirror device24. The strenght of these fields can be easily varied as a function of time, thus implementing the sweep coefficients At and Bt in equation (2).

To implement the two-body interactions of equation (3) we turn to the technique of Rydberg dressing25,26,27,28, where off-resonant laser light weakly admixes some Rydberg character into the ground state levels  , leading to an effective interaction between them. For large laser detunings, the Rydberg dressing acts as a perturbation and the dressed levels predominantly retain their ground state character and remain trapped29. Interactions between two spins i and j arise, as spatially dependent light shifts

, leading to an effective interaction between them. For large laser detunings, the Rydberg dressing acts as a perturbation and the dressed levels predominantly retain their ground state character and remain trapped29. Interactions between two spins i and j arise, as spatially dependent light shifts  and

and  of the dressed pair states

of the dressed pair states  and

and  , respectively. These pair states are coupled via two photon excitations to doubly excited Rydberg states. Because of multipole–multipole interactions, the energies of the doubly excited Rydberg states vary strongly as a function of the relative position Rij of the atoms, and can exceed typical laser detunings and coupling strengths even at micrometre distances. This strongly affects the light shifts of the dressed pair ground states, thus endowing them with an effective interaction.

, respectively. These pair states are coupled via two photon excitations to doubly excited Rydberg states. Because of multipole–multipole interactions, the energies of the doubly excited Rydberg states vary strongly as a function of the relative position Rij of the atoms, and can exceed typical laser detunings and coupling strengths even at micrometre distances. This strongly affects the light shifts of the dressed pair ground states, thus endowing them with an effective interaction.

Here, we propose to couple the  and

and  states of Rb and Cs using single photon transitions to the mJ=−1/2 magnetic sublevels of Rydberg P states16,17,30,31,32,33,34, with laser light that is linearly polarized along the z axis and thus retains the symmetry of the lattice geometry. Figure 3 shows the Rydberg pair energies in the presence of multipole interactions, in the vicinity of (a) the

states of Rb and Cs using single photon transitions to the mJ=−1/2 magnetic sublevels of Rydberg P states16,17,30,31,32,33,34, with laser light that is linearly polarized along the z axis and thus retains the symmetry of the lattice geometry. Figure 3 shows the Rydberg pair energies in the presence of multipole interactions, in the vicinity of (a) the  and (b) the

and (b) the  Rydberg states of 87Rb and (c) the mixed

Rydberg states of 87Rb and (c) the mixed  Rydberg states. The pair potentials are obtained from an exact diagonalization calculation (Supplementary Note 2), including interactions up to quadrupole–quadrupole and dipole–octupole couplings. In the regime of strong interactions, the Rydberg states are mixed by the multipole couplings, and each energy level corresponds to a superposition of Rydberg states with a variety of quantum numbers. The blue colouring in Fig. 3 represents the overlap with the laser targeted mJ=−1/2 states, and is therefore indicative of the effective coupling strength to the pair ground states. Although there are many energy levels in the regime of interest, we see that at distances >0.5 μm only a handful of potential curves is significantly coupled by the dressing laser, while the vast majority of states (grey curves) is only coupled with negligible strengths.

Rydberg states. The pair potentials are obtained from an exact diagonalization calculation (Supplementary Note 2), including interactions up to quadrupole–quadrupole and dipole–octupole couplings. In the regime of strong interactions, the Rydberg states are mixed by the multipole couplings, and each energy level corresponds to a superposition of Rydberg states with a variety of quantum numbers. The blue colouring in Fig. 3 represents the overlap with the laser targeted mJ=−1/2 states, and is therefore indicative of the effective coupling strength to the pair ground states. Although there are many energy levels in the regime of interest, we see that at distances >0.5 μm only a handful of potential curves is significantly coupled by the dressing laser, while the vast majority of states (grey curves) is only coupled with negligible strengths.

Rydberg-Rydberg interaction energies E around the (a)  and (b)

and (b)  states of 87Rb and c the mixed

states of 87Rb and c the mixed  Rydberg state of 133Cs and 87Rb, in a magnetic field of Bz=26 G along the z axis. The intensity of the blue colouring indicates the overlap with the laser-targeted Rydberg states. The most strongly coupled pair potentials feature distinct local minima, which can be exploited in an enhanced Rydberg dressing scheme by detuning the Rydberg dressing laser such that, in the rotating frame, the pair ground state energies (green line for the

Rydberg state of 133Cs and 87Rb, in a magnetic field of Bz=26 G along the z axis. The intensity of the blue colouring indicates the overlap with the laser-targeted Rydberg states. The most strongly coupled pair potentials feature distinct local minima, which can be exploited in an enhanced Rydberg dressing scheme by detuning the Rydberg dressing laser such that, in the rotating frame, the pair ground state energies (green line for the  state in a,b, and yellow line for the

state in a,b, and yellow line for the  state in (c) approach the minima of the potential wells. This configuration leads to relatively large and strongly peaked level shifts of the dressed ground states, as can be seen in d which shows the resulting interaction potential U++ between two Rydberg-dressed Rb–Cs (yellow) and Rb–Rb (green) ground state atoms. Drastically enhanced peaked-like interactions appear at

state in (c) approach the minima of the potential wells. This configuration leads to relatively large and strongly peaked level shifts of the dressed ground states, as can be seen in d which shows the resulting interaction potential U++ between two Rydberg-dressed Rb–Cs (yellow) and Rb–Rb (green) ground state atoms. Drastically enhanced peaked-like interactions appear at  , aL and

, aL and  , thereby realizing the required plaquette interaction of equation (3) for α=2 and β=1. Vertical dashed lines connect the extrema in the ground state level shifts to the corresponding Rydberg potential minima in the excited state manifold. Various resonances due to accidental degeneracies of the ground states with weakly coupled excited states are visible as well, but these are of negligible width and occur away from lattice sites.

, thereby realizing the required plaquette interaction of equation (3) for α=2 and β=1. Vertical dashed lines connect the extrema in the ground state level shifts to the corresponding Rydberg potential minima in the excited state manifold. Various resonances due to accidental degeneracies of the ground states with weakly coupled excited states are visible as well, but these are of negligible width and occur away from lattice sites.

The particular Rydberg P pair states shown in Fig. 3(a–c) feature pronounced potential wells which enable an enhanced Rydberg dressing scheme19. For this purpose, we tune the (two-photon) detuning of the dressing laser such that, in the rotating frame, the energy of the ground pair states (green line in Fig. 3(a,b) for  , and yellow line in panel (c)) is close to a potential minimum. This gives rise to pronounced light shifts of the pair ground states at the point of closest approach, as shown in Fig. 3(d), while at the same time producing negligible light shifts elsewhere. The particular Rydberg states in Fig. 3(a–c) are chosen such that the dressed ground state potentials

, and yellow line in panel (c)) is close to a potential minimum. This gives rise to pronounced light shifts of the pair ground states at the point of closest approach, as shown in Fig. 3(d), while at the same time producing negligible light shifts elsewhere. The particular Rydberg states in Fig. 3(a–c) are chosen such that the dressed ground state potentials  and

and  plotted in Fig. 3(d) show peaks at distances

plotted in Fig. 3(d) show peaks at distances  , aL and

, aL and  , commensurate with a square lattice geometry with aL=0.89 μm. Accidental crossings of the doubly excited Rydberg levels with the pair ground state energy give rise to resonances in the dressed state level shifts, but these either occur at distances which are not present in the lattice geometry, or they are of negligible width on behalf of a vanishing laser coupling strength to the crossing states.

, commensurate with a square lattice geometry with aL=0.89 μm. Accidental crossings of the doubly excited Rydberg levels with the pair ground state energy give rise to resonances in the dressed state level shifts, but these either occur at distances which are not present in the lattice geometry, or they are of negligible width on behalf of a vanishing laser coupling strength to the crossing states.

Rydberg annealer

The final spin–spin interactions, following from the light shifts described in the previous Section, are given by

apart from additional single-particle corrections to the local fields. The height of the two peaks of  at aL and

at aL and  for Rb-Rb (green line in Fig. 3(d)) and of

for Rb-Rb (green line in Fig. 3(d)) and of  at

at  for Rb–Cs (yellow line in Fig. 3(d)) can be tuned by varying the Rabi frequencies and detunings of the dressing laser. In particular, we choose Rabi frequencies Ω1=Ω2=2π × 35 MHz, ΩC=2π × 30 MHz and detunings Δ1=−2π × 618 MHz, Δ2=−2π × 373 MHz and ΔC=2π × 175 MHz which leads to light-shifts of

for Rb–Cs (yellow line in Fig. 3(d)) can be tuned by varying the Rabi frequencies and detunings of the dressing laser. In particular, we choose Rabi frequencies Ω1=Ω2=2π × 35 MHz, ΩC=2π × 30 MHz and detunings Δ1=−2π × 618 MHz, Δ2=−2π × 373 MHz and ΔC=2π × 175 MHz which leads to light-shifts of  for Rb–Rb and

for Rb–Rb and  for Rb–Cs (Supplementary Note 2). We note that an external magnetic field and small vertical offset of the Cs atoms are used to obtain the final interaction strengths and precisely align the potential extrema with plaquette distances (Supplementary Note 2).

for Rb–Cs (Supplementary Note 2). We note that an external magnetic field and small vertical offset of the Cs atoms are used to obtain the final interaction strengths and precisely align the potential extrema with plaquette distances (Supplementary Note 2).

All interactions between atoms (spins and ancillas) that are not part of a common plaquette are at least two orders of magnitude smaller than the interactions within a plaquette. This allows us to restrict the sum in equation (4) to pairs of atoms belonging to the same plaquette, thus realizing  of equation (3) for the optimal parameters α=2 and β=1. For the above system parameters, we obtain a final energy gap Δ□=−2π × 20 kHz. Note that the energy gap is negative, which can be easily accounted for by a sign change of all local fields and making the annealer adiabatically follow the maximum energy state, instead of the minimum.

of equation (3) for the optimal parameters α=2 and β=1. For the above system parameters, we obtain a final energy gap Δ□=−2π × 20 kHz. Note that the energy gap is negative, which can be easily accounted for by a sign change of all local fields and making the annealer adiabatically follow the maximum energy state, instead of the minimum.

Because of the finite lifetime of the Rydberg states, the dressed ground state interactions come at a cost of an effective decoherence rate 1/τ0 for each qubit. However, as there is only a small Rydberg component admixed, the effective decay rate is also only a correspondingly small fraction of the bare Rydberg decay rate. Ultimately, the figure of merit for fully coherent operation of the quantum annealer is the ratio of the attained interaction strength versus the effective decay rate. In the enhanced dressing scheme this ratio becomes particularly favourable and is of the order of  for the system parameters above (Supplementary Note 2).

for the system parameters above (Supplementary Note 2).

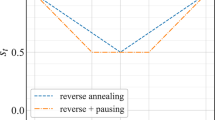

Using the above potentials we demonstrate numerically the feasibility of the Rydberg annealer for the minimal instance (Fig. 1) with eight qubits and three ancillas. Figure 4 depicts the time dependent spectrum in reduced units for an instance of Hamiltonian equation (2) for random  . The sweep functions At, Bt and Ct are simple linear functions. Note, that the efficiency can be considerably increased by adopting non-linear sweep functions. In Fig. 4 all energies are given relative to the ground state energy. The pronounced minimal gap is an order of magnitude smaller than the gap in the final state. Figure 4(b) shows the histogram of the success probability

. The sweep functions At, Bt and Ct are simple linear functions. Note, that the efficiency can be considerably increased by adopting non-linear sweep functions. In Fig. 4 all energies are given relative to the ground state energy. The pronounced minimal gap is an order of magnitude smaller than the gap in the final state. Figure 4(b) shows the histogram of the success probability  , defined as the overlap of the final state

, defined as the overlap of the final state  with the ground state

with the ground state  , averaged over Nr=40 random instances for different sweep times far below the decoherence times τ<τ0/K. For the fastest switching time

, averaged over Nr=40 random instances for different sweep times far below the decoherence times τ<τ0/K. For the fastest switching time  the average success probability is 75% and approaches unity for slower sweeps.

the average success probability is 75% and approaches unity for slower sweeps.

(a) Illustration of the time-dependent spectrum for the minimal instance shown in Fig. 1. (b) Histogram of the success probability, that is, the probability P0 to populate the ground state at final time τ for different sweep times.

Discussion

The proposed implementation of a quantum annealer with ultracold Rydberg atoms in optical lattices provides a platform for adiabatic quantum computing, featuring a highly controllable environment to explore the many-body adiabatic passage, the role of entanglement and effects of decoherence during the annealing sweep. The large lifetimes of Rydberg dressed atoms enable coherent quantum annealing as an alternative to the current paradigm of quantum enhanced thermal annealing35. We anticipate that due to the coherent evolution the number of spins in future experiments can readily be extended well beyond the minimal example presented here, by using shorter annealing cycles with many repetitions36, or by employing counter-diabatic driving schemes that could greatly increase the attained fidelities7. Finally, our proposal allows to realize atomic quantum simulators of arbitrary infinite-range Ising spin glass models (see, for example, references in ref. 37), and the combination of multi-color Rydberg-dressed interactions with two-species mixtures has applications in realizing  lattice gauge theories beyond the present example38.

lattice gauge theories beyond the present example38.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Glaetzle, A. W. et al. A coherent quantum annealer with Rydberg atoms. Nat. Commun. 8, 15813 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15813 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Kadowaki, T. & Nishimori, H. Quantum annealing in the transverse ising model. Phys. Rev. E 58, 5355–5363 (1998).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., Gutmann, S. & Sipser, M. Quantum Computation by Adiabatic Evolution. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0001106 (2000).

Boixo, S. et al. Evidence for quantum annealing with more than one hundred qubits. Nat. Phys. 10, 218–224 (2014).

Boixo, S. et al. Computational multiqubit tunnelling in programmable quantum annealers. Nat. Commun. 7, 10327 (2016).

Lucas, A. Ising formulations of many np problems. Front. Phys. 2, 5 (2014).

Dickson, N. G. et al. Thermally assisted quantum annealing of a 16-qubit problem. Nat. Commun. 4, 1903 (2013).

Sels, D. & Polkovnikov, A. Minimizing irreversible losses in quantum systems by local counter-diabatic driving, Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.05687 (2016).

Graß, T. & Lewenstein, M. Hybrid annealing using a quantum simulator coupled to a classical computer. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.09729 (2016).

Matsuda, Y., Nishimori, H. & Katzgraber, H. G. Ground-state statistics from annealing algorithms: quantum versus classical approaches. N. J. Phys. 11, 073021 (2009).

Bravyi, S., Divincenzo, D. P., Oliveira, R. I. & Terhal, B. M. The complexity of stoquastic local hamiltonian problems. Quant. Inf. Comput. 8, 361–385 (2008).

Nishimori, H. & Takada, K. Exponential enhancement of the efficiency of quantum annealing by non-stoquastic hamiltonians. Front. ICT 4, 2 (2017).

Lechner, W., Hauke, P. & Zoller, P. A quantum annealing architecture with all-to-all connectivity from local interactions. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500838 (2015).

Rocchetto, A., Benjamin, S. C. & Li, Y. Stabilizers as a design tool for new forms of the lechner-hauke-zoller annealer. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601246 (2016).

Schauß, P. et al. Crystallization in ising quantum magnets. Science 347, 1455–1458 (2015).

Maller, K. M. et al. Rydberg-blockade controlled-not gate and entanglement in a two-dimensional array of neutral-atom qubits. Phys. Rev. A 92, 022336 (2015).

Zeiher, J. et al. Many-body interferometry of a rydberg-dressed spin lattice. Nat. Phys. 12, 1095–1099 (2016).

Jau, Y.-Y., Hankin, A. M., Keating, T., Deutsch, I. H. & Biedermann, G. W. Entangling atomic spins with a rydberg-dressed spin-flip blockade. Nat. Phys. 12, 71 (2016).

Labuhn, H. et al. Tunable two-dimensional arrays of single Rydberg atoms for realizing quantum Ising models. Nature 534, 667–670 (2016).

van Bijnen, R. M. W. & Pohl, T. Quantum magnetism and topological ordering via rydberg dressing near förster resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 243002 (2015).

Beterov, I. I. & Saffman, M. Rydberg blockade, förster resonances, and quantum state measurements with different atomic species. Phys. Rev. A 92, 042710 (2015).

Reichsöllner, L., Schindewolf, A., Takekoshi, T., Grimm, R. & Nägerl, H.-C. Quantum engineering of a low-entropy gas of heteronuclear bosonic molecules in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 073201 (2017).

Barredo, D., de Léséleuc, S., Lienhard, V., Lahaye, T. & Browaeys, A. An atom-by-atom assembler of defect-free arbitrary two-dimensional atomic arrays. Science 354, 1021–1023 (2016).

Endres, M. et al. Atom-by-atom assembly of defect-free one-dimensional cold atom arrays. Science 354, 1024–1027 (2016).

Fukuhara, T. et al. Quantum dynamics of a mobile spin impurity. Nat. Phys. 9, 235–241 (2013).

Pupillo, G., Micheli, A., Boninsegni, M., Lesanovsky, I. & Zoller, P. Strongly correlated gases of rydberg-dressed atoms: quantum and classical dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 223002 (2010).

Henkel, N., Nath, R. & Pohl, T. Three-dimensional roton excitations and supersolid formation in rydberg-excited bose-einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 195302 (2010).

Honer, J., Weimer, H., Pfau, T. & Büchler, H. P. Collective many-body interaction in rydberg dressed atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 160404 (2010).

Johnson, J. E. & Rolston, S. L. Interactions between rydberg-dressed atoms. Phys. Rev. A 82, 033412 (2010).

Macrì, T. & Pohl, T. Rydberg dressing of atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 89, 011402 (2014).

Weber, T. M. et al. Mesoscopic Rydberg-blockaded ensembles in the superatom regime and beyond. Nat. Phys. 11, 157–161 (2015).

Faoro, R. et al. Borromean three-body FRET in frozen Rydberg gases. Nat. Commun. 6, 8173 (2015).

Glaetzle, A. W. et al. Quantum Spin-Ice and Dimer Models with Rydberg Atoms. Phys. Rev. X. 4, 041037 (2014).

Glaetzle, A. W. Designing Frustrated Quantum Magnets with LaserDressed Rydberg Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 173002 (2015).

Vermersch, B., Glaetzle, A. W. & Zoller, P. Magic distances in the blockade mechanism of Rydberg p and d states. Phys. Rev. A 91, 023411 (2015).

Amin, M. H. Searching for quantum speedup in quasistatic quantum annealers. Phys. Rev. A 92, 052323 (2015).

Knysh, S. Zero-temperature quantum annealing bottlenecks in the spin-glass phase. Nat. Commun. 7, 052504 (2016).

Katzgraber, H. G. Spin glasses and algorithm benchmarks: a one-dimensional view. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 95, 012004 (2008).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge discussions with C. Gross, H.C. Nägerl, M. Saffman and J. Zeiher. This work is supported by the Austrian Science Fund SFB FoQuS (FWF Project No. F4016-N23), the European Research Council (ERC) Synergy Grant UQUAM and the EU H2020 FET Proactive project RySQ. W.L. acknowledges funding from the Hauser-Raspe Foundation. The computational results presented have been achieved (in part) using the HPC infrastructure LEO of the University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed extensively to all aspects of this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References. (PDF 221 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Glaetzle, A., van Bijnen, R., Zoller, P. et al. A coherent quantum annealer with Rydberg atoms. Nat Commun 8, 15813 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15813

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15813

This article is cited by

-

Scalable set of reversible parity gates for integer factorization

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Scalable quantum processors empowered by the Fermi scattering of Rydberg electrons

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Fast spin squeezing by distance-selective long-range interactions with Rydberg molecule dressing

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2022)

-

Prospects for quantum enhancement with diabatic quantum annealing

Nature Reviews Physics (2021)

-

Enhancing quantum annealing performance by a degenerate two-level system

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.