Abstract

Catalysing the reduction of oxygen in acidic media is a standing challenge. Although activity of platinum, the most active metal, can be substantially improved by alloying, alloy stability remains a concern. Here we report that platinum nanoparticles supported on graphite-rich boron carbide show a 50–100% increase in activity in acidic media and improved cycle stability compared to commercial carbon supported platinum nanoparticles. Transmission electron microscopy and x-ray absorption fine structure analysis confirm similar platinum nanoparticle shapes, sizes, lattice parameters, and cluster packing on both supports, while x-ray photoelectron and absorption spectroscopy demonstrate a change in electronic structure. This shows that purely electronic metal-support interactions can significantly improve oxygen reduction activity without inducing shape, alloying or strain effects and without compromising stability. Optimizing the electronic interaction between the catalyst and support is, therefore, a promising approach for advanced electrocatalysts where optimizing the catalytic nanoparticles themselves is constrained by other concerns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is a standing grand challenge in fundamental research in energy, exemplifying a broader class of multi-electron reactions1. Oxygen reduction efficiency and long-term catalyst stability are standing fundamental problems that have to be overcome for polymer electrolyte fuel cells2 to be used in demanding applications such as automobiles and grid-scale energy storage. The relatively large overpotential of the ORR at technically feasible electrodes under practical operating conditions limits conversion efficiency to typically <50% relative to the thermodynamic limit of more than 80% (ref. 3). Challenging cost targets, especially in the automotive industry, provide further motivation to reduce Pt loadings4. Finally, the dissolution and/or loss of Pt surface area in the cathode must be greatly reduced to meet automotive and grid-scale storage stability targets.

The work pioneered by Nørskov5 has provided a rational design approach to improve ORR activity by tailoring the position of the Pt d-band centre, because it determines the stability of reaction intermediates, especial Oads. Significant efforts have successfully focused on improving ORR activity by d-band centre engineering via nanoparticulate Pt alloys supported on high-surface area carbon2,6,7,8. However, the most active alloys3,9 are unlikely to show long-term stability under cathodic polymer electrolyte fuel cells conditions10,11 for thermodynamic reasons. At best, one can hope that dealloying is restricted to the surface, leading to Pt skin structures that are, fortuitously, highly active3,12,13.

Whether dealloying can be restricted to the surface of the typically 2 nm alloy electrocatalysts over technically relevant lifetimes is an open question. Regardless, stability concerns motivate other design approaches to engineer the Pt d-band characteristics without potentially compromising stability. Recently, research emphasis has shifted to alternative support materials to prevent the loss of catalyst surface area due to support corrosion and dissolution/agglomeration of nanoparticulate Pt (refs 14, 15). Alternative supports also provide an opportunity to indirectly improve ORR activity as well, because a change in support electronic structure can influence the catalyst’s d-band manifold via electronic equilibration16, one aspect of strong metal-support interactions (SMSI).

Utilization of SMSIs is a promising approach to improve both activity and stability of supported Pt catalysts. The SMSI of Pt on oxide supports, particularly titanium dioxide, is well known17,18. These Pt/TiO2 catalysts have previously exhibited higher activities for ORR in relation to Pt/C (ref. 19). The low conductivity of these materials, however, is a challenge20. Highly conductive SnO2-based supports have, therefore, attracted attention recently21, and thin film studies unveiled an intriguing dependence of ORR activity on support orientation and/or termination22.

Changing the physical nature of the support from carbons to oxides is a radical step. It potentially impacts catalyst stoichiometry and particle morphology, which in their own right change electrocatalytic properties via size4, strain23 and proximity24 effects. It is, therefore, nontrivial to experimentally isolate these effects to develop the fundamental understanding needed to rationally exploit SMSIs.

Transition metal carbides have also been widely investigated as promising support materials due to high electrical conductivity, thermal stability and similarities in electronic structure to Pt (ref. 25). However, the low surface area of carbides and liability to oxidation are challenging26. Carbides are, nonetheless, attractive to investigate electronic metal-support interactions in isolation, because they are physically closer to carbon than oxides. The material of choice, however, should also show a markedly different electronic structure and resilience against oxidation. Boron carbide (B4C) is such a material. It is a refractory compound26 exhibiting high chemical inertness27, semi-conducing band structure and electrochemical stability28. The first study of B4C as an electrocatalyst support for hydrogen fuel cells was by Grubb & McKee29 wherein a high resistance to sintering and higher current densities when compared to platinum on carbon black were already observed. More recent work by Lv et al.30 has also shown promising ORR activity.

Pt nanoparticle supported on graphite-rich B4C composites (BC) are compared here with Pt supported on Vulcan XC 72R high-surface area carbon (C) to isolate electronic metal-support interactions. Electrochemical as well as advanced ex situ characterization techniques are used to elucidate the structure-property relationships between catalyst morphology, electronic structure and ORR activity. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis confirm similar particle size, shape and packing of the clustered nanoparticles on both supports, while X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray adsorption near edge structure (XANES) analysis show differences in electronic properties due to metal-support interactions. These differences in electronic properties are correlated with enhanced ORR activity: the surface and mass specific oxygen reduction activity of Pt nanoparticles supported on BC under rotating disc electrode (RDE) conditions increases by roughly 40% relative to commercial Pt/C, while the kinetic current at 0.9 V shows a 50–100% improvement. The increased cycle stability of the BC supported catalysts after degradation cycling further promotes the interpretation in terms of increased electronic metal-support interactions on these catalysts. Purely electronic metal-support interactions are, therefore, experimentally isolated demonstrating that optimizing the electronic interaction between the catalyst and support, in conjunction with d-band theory, is a promising approach to designing advanced electrocatalysts without compromising stability under harsh conditions.

Results

Naming scheme

Graphite-rich boron carbide composites (BC) were catalysed with varying amounts of Pt nanoparticles following standard procedures. These Pt/BC catalysts are compared with commercial Pt/C catalysts. It is imperative to keep particle size and dispersion constant between the Pt/BC and benchmark Pt/C catalysts to isolate electronic effects, because these affect ORR activities significantly4,23,24. We use a naming convention for all catalysts that follows the nominal platinum loading (that is, wt%) of the commercial benchmark catalysts. The equivalent platinum loading on BC (that is, eq. wt%) designates a catalyst that has the same mass platinum per support surface area (Supplementary Note 1).

Support surface area

The BC support Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET) surface area was measured to be 80 m2g−1, in agreement with manufacturer specifications (Supplementary Fig. 1). This is considerably lower than seen for high-surface area carbons such as Vulcan XC 72R, which has a surface area of 250–260 m2g−1. To keep the mass platinum per surface area constant, the actual target platinum loading per mass BC support was, therefore, reduced accordingly (Supplementary Table 1) to maintain a similar Pt coverage per surface area of support and particle size as seen on the commercial Pt/C benchmark catalysts to isolate support-related activity changes.

X-ray diffraction

The X-ray diffraction pattern of BC (Supplementary Fig. 2) clearly shows peaks indicative of rhombohedral graphite (3R) and hexagonal graphite (2H) in addition to rhombohedral B4C (R3m), showing the material to be a composite of graphite and rhombohedral B4C. Using Rietveld refinement, the spectrum indicates 58.0±7.7 wt% graphite, 38.7±7.2 wt% B4C and 3.0±1.7 wt% B2O in the sample. This is in reasonable agreement with the average B:C ratio of 39:61 as obtained from EELS. The high graphite content ensures comparative conductivities between BC and C (Supplementary Note 2). The graphite consists of approximately 32.0 wt% rhombohedral graphite (3R) and 26.0 wt% hexagonal graphite (2H).

The average Pt crystallite size was confirmed by a fit of the Scherrer equation to the Pt(200), Pt(220) and Pt(311) peaks at 46°, 67° and 81° in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). This analysis yielded a volume-weighted average particle size of ∼3.9 nm for the various loadings, in good agreement with the size measured via TEM (Table 1). XRD routinely overestimates particle size compared to TEM at the relevant length scale, because particle sizes smaller than 2 nm are not identified due to the lower detection limit of XRD (ref. 31).

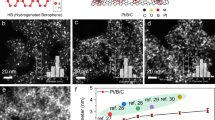

Transmission electron microscopy

TEM images of the prepared Pt/BC catalysts as well as the as-received commercial Pt/C benchmark catalysts, taken at 270 k times magnification to illustrate particle dispersion and support morphology, are shown in Fig. 1. The Pt loadings on BC were confirmed via ICP-OES analysis to be 10, 20 and 40 eq. wt%, respectively (see Supplementary Table 1 for actual loadings). Pt particle size distribution and dispersion for each catalyst are quantified and contrasted in Table 1, which shows average particle size with s.d. as well as average interparticle distances with s.d.

The BC support particles are homogenous with an average particle size of ∼40 nm, and Pt nanoparticles are well dispersed on the BC support with average particle sizes ranging from 2.3 to 2.9 nm. Particle size and interparticle distances are very similar for equivalent loadings on both supports at 20 wt% and 40 wt% with little s.d. Non-conformity is seen between the 10 wt% Pt/C and 10 eq wt% Pt/BC catalysts due to the unusually small Pt size on Pt/C.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

The EXAFS was collected for the 20 eq. wt% Pt/BC and 20 wt% Pt/C catalysts. The EXAFS at the Pt L3 edge gives insights to the supported Pt morphology: the first shell co-ordination number is strongly related to average particle size32 while the fourth co-ordination number is an indication of particle shape.

The measured and modelled EXAFS spectra are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The fitted model, considering up to the fourth neighbour shells, describes the EXAFS data well. The resulting co-ordination numbers (N), distances of neighbouring atoms (R) and the disorder factors (σ2) of the catalysts supported on BC and C are listed in Table 2.

The first, second and fourth Pt co-ordination numbers are slightly smaller for Pt supported on BC, while the third is found to be slightly larger. Differences, however, are within experimental error indicating very similar Pt morphologies as further discussed later. Near-neighbour distances also agree very well between the Pt/BC and Pt/C catalysts.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

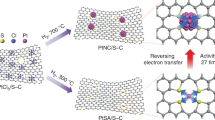

Figure 2a shows the C 1s and Pt 4f regions of XPS spectra for the Pt/BC and Pt/C catalysts. The XPS spectra are calibrated via alignment of the C(sp2) peak position in the C 1s spectrum to its reference value of 284 eV.

(a) XPS spectra of the C 1 s and Pt 4f region of the Pt/C and Pt/BC catalysts, spectra are aligned to the graphitic C (sp2) peak at 284 eV; (b) Schematic of charge transfer across the support-catalyst interface due to Fermi level equilibration rationalizing relative shifts in the XPS Pt 4f and C 1 s core levels; (c) In situ XANES L2 and L3 edge measured at 744 mV versus NHE probing d-band occupancy in electrochemical environment.

The C 1s region of the Pt/C catalyst is dominated by the C(sp2) peak with a small, broad feature at higher binding energies that has been assigned to C–O bonding structures of carboxyl groups33. The C 1 s spectrum of the Pt/BC catalysts is a convolution of contributions from the B4C and graphitic carbon within the composite. The C(sp2) peak is assigned to the graphitic carbon, and the peaks at 282.7 and 284.8 eV are attributed to B4C. The low energy polymorphs of B4C (ref. 34) provide three C environments at the ends and centre of tri-atomic chains and in the polar position within B11C icosahedra. The low binding energy peak at 282.7 eV was previously attributed to B4C (ref. 35) and is likely due to carbon in low co-ordination (chain centre and/or B11C). The C(sp3) peak at 284.8 eV, which is reminiscent of diamond36, is also predominantly assigned to B4C due to the strong similarity of site environment of tetrahedral carbon at the chain ends in B4C and diamond and the lack of evidence for sp3 hybridized carbon from XRD.

This assignment is supported by density functional theory calculations (Supplementary Note 3) that predict a chemical shift of ∼2.3 eV between the C 1s core electrons in B11C and CBC units (Supplementary Table 2), in good agreement with the experimental shift of 2.1 eV. Hence, the relative strength of the C(sp2) and C(sp3) peaks corroborates the phase fractions of B4C and graphitic carbon within the composite derived from XRD.

The Pt 4f spectra of the Pt/C catalyst features the usual spin–orbit splitting into a 4f7/2 peak at 71.0 eV and a 4f5/2 peak at 74.3 eV. The same splitting is seen for all Pt/BC catalysts. There is, however, a clear shift of both peaks by ∼0.6 eV to higher binding energies for all Pt loadings on BC to 71.6 and 74.9 eV.

In situ x-ray absorption near edge structure

Figure 2c shows the XANES Pt L2 and L3 edges for the 20 wt% Pt/C and 20 eq. wt% Pt/BC catalysts measured under potentiostatic control in electrochemical environment. The increase in the L2 white line observed for the Pt/BC catalyst indicates an increase in unoccupied d-states above the Fermi level for Pt/BC (ref. 37) in electrochemical environments. Using standard post-processing38, d-band occupancy can be estimated to be 63% for Pt/C and 58% for Pt/BC at 0.744 V versus NHE.

Electrochemical characteristics and activity

The calculated electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) and ORR activities are summarized in Table 3. CO stripping voltammetry (Supplementary Fig. 5) was used to determine the ECSAs assuming a specific charge of 420 μCcmPt−2 per CO monolayer adsorbed on the platinum surface. Measurements were taken at room temperature in 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte solution. No CO stripping peak was seen on the uncatalysed BC support. ECSAs were confirmed using Cu-UPD39.

The specific and kinetic currents reported in Table 3 were obtained from RDE measurements at a rotation speed of 1,600 r.p.m. (Supplementary Fig. 6) during the anodic sweep at 0.9 V versus RHE. Measurements were completed at 20 mVs−1 to minimize double layer charging artefacts at room temperature in an oxygen saturated 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte4,40. The ECSA obtained from CO stripping voltammetry was used to calculate surface area specific currents, and the kinetic current was isolated from mass transport limitations using standard post-processing41.

The Pt/C catalyst activities fall in line with numerous reported values and compilations of values for ORR activity on these catalysts4,42,43,44,45. An exception is seen for the 10 wt% Pt/C catalyst, which exhibited large experimental scatter and anomalously small limiting currents during RDE measurements (Supplementary Fig. 6a) indicative of various detrimental effects43. The 10% Pt/C catalyst is, therefore, not considered a suitable benchmark for our purposes.

The ORR activities for the BC supported catalysts consistently show a more active catalyst with higher mass specific (Imass), surface area specific (Ispec) and kinetic activities (Ik) for the ORR. Additionally, kinetic activity increases as Pt loading increases on both the Pt/C and Pt/BC catalysts, with the least active ORR catalyst being 10 wt% Pt/C and the most active being 40 eq wt% Pt/BC. These trends are further discussed below.

Further electrochemical characteristics are summarized in Fig. 3. Cyclic voltammograms of the BC supported catalysts are shown in the left diagram of Fig. 3a. In addition to the typical characteristics of supported Pt, a slight coupled reversible reaction at ∼0.6 V versus RHE is seen for the Pt/BC materials. The large double layer of the Pt/BC catalysts results in a less well defined HUPD region than seen on the Pt/C catalysts. Therefore, no attempt was made to compare the ECSA as obtainable from the HUPD region with the values given in Table 3. Careful observation of the cyclic votammograms in Fig. 3b, which compares the electrochemical response of Pt/BC with the Pt/C benchmark at 40 wt%, shows slight peak shifts towards higher potentials in the oxide reduction region for Pt/BC.

(a) Shows cyclic voltammograms and Tafel plots for 10, 20 and 40 eq wt% Pt/BC, and (b) compares 40 eq wt% Pt/BC with 40 wt% Pt; CVs recorded at 20 mVs−1 between 0.05 and 1.2 V versus RHE and normalized for surface area specific current, Tafel plots obtained from anodic scan recorded at 1,600 r.p.m. between 0.05 and 1.2 V versus RHE and normalized for surface area specific current; all experiments performed in 0.1 M HClO4 at room temperature.

The kinetic ORR results are reiterated in the Tafel plots shown to the right in Fig. 3 for completeness. Figure 3a compares kinetic currents of Pt/BC at various loadings. Again, kinetic activity generally increases with Pt loading over the full potential range although the two lower loadings show comparable kinetic currents at lower voltages. Finally, the Tafel plot of Fig. 3b shows that the 40 eq wt% Pt/BC catalyst exhibits higher kinetic activity for ORR over the measured potential range of 0.85–0.95 V versus RHE than the 40 wt% Pt/C benchmark. In fact, relative activity of Pt/BC versus Pt/C seems to increase further with decreasing potential.

Cycle stability

Catalyst durability was studied for the most active Pt/BC and Pt/C catalysts to investigate the platinum dissolution and platinum agglomeration rate on the different supports. Durability testing consisted of cycling the potential between 0.6 and 1.0 V versus RHE for 6,000 cycles at a scan rate of 50 mVs−1 and periodically returning to the full voltammogram scan (0.05–1.2 V versus RHE at 20 mVs−1) to compare changes in the HUPD region and oxygen adsorption and desorption region.

The voltammograms of the Pt/BC catalyst show significantly less change after 6,000 cycles compared to Pt/C (Fig. 4a). Changes in the 1.0–1.2 V range for Pt/BC appear to be not purely related to ECSA loss, because less variation is seen in the HUPD region after cycling. Instead, the reduced current response in the oxidative region is in parts attributed to secondary conditioning effects, which could either be the removal of organic impurities from Pt or oxidative decomposition of other trace impurities in solution amongst other things.

Cyclic voltammograms of Pt/C before and after cycling show a significantly altered current response in the oxide as well as in the HUPD region while the double layer region remains invariant after 6,000 cycles, strongly suggesting catalyst degradation and ECSA loss.

The ECSAs shown in Fig. 4b were periodically obtained from the HUPD region. Both catalysts show a relatively stable ECSA for an initial period of ∼50–100 cycles, which might be due to cleaning and/or roughening effects offsetting initial degradation. A logarithmic loss of ECSA is seen for both catalysts beyond this initial conditioning phase. Focusing on the data from cycle 300 onwards, the Pt/C catalyst loses 14.7% ECSA per decade, while the Pt/BC catalysts shows only 9.8% ECSA loss per decade, a 1/3 reduction in logarithmic degradation rate.

ORR activity of cycled catalysts as obtained from RDE measurements (Supplementary Fig. 7) is compared with ORR activity of the pristine catalysts in Table 4 for one set of catalysts. For consistency, specific and kinetic activities are based on ECSAs measured again after 6,000 cycles by CO stripping (Supplementary Fig. 8). The ECSAs reported in Table 4 agree well with the cyclic H-UPD measurements (Fig. 4), showing a significantly larger loss in surface area for the Pt/C catalyst (23% loss after 6,000 cycles) than for the Pt/BC catalyst (12% loss after 6,000 cycles). Accordingly, mass activity of the cycled Pt/BC catalyst remains with 168A per gPt ∼30% higher than seen for the cycled Pt/C catalyst. Relative loss of mass, specific and kinetic activity of the Pt/BC catalyst are in reasonable agreement with the loss in ECSA for the Pt/BC catalyst. The Pt/C catalyst, however, shows a markedly different behaviour. While mass activity also degrades, the relative loss in mass activity (9% loss) is smaller than the reduction in ECSA (23% loss). Correspondingly, surface specific and kinetic activities increase for reasons discussed later. Nonetheless, kinetic activity of the cycled Pt/C catalyst remains significantly lower than seen for the Pt/BC catalyst after 6,000 cycles.

Platinum nanoparticle size and shape

Platinum was successfully deposited onto BC with the same average particle sizes as on carbon supports (with the exception of 10 wt% Pt/C) and similar particle size distributions (Table 1 and Fig. 1). There is no significant increase in particle size for the higher loadings, indicating that the surface area for both supports is sufficient to accommodate high loadings of nanoparticles.

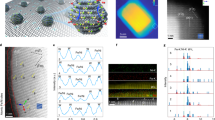

Figure 5 compares the Pt–Pt co-ordination numbers obtained from EXAFS results presented in Table 2 with co-ordination numbers for ideal icosahedra and cubocahedra46. The first four Pt–Pt co-ordination numbers are plotted against average number of atoms per particle as obtained from TEM. The error margins are calculated from the TEM particle size distributions and the confidence interval of the modelled parameters as given by Demeter47.

Co-ordination numbers N1 through N4 for icosahedra and cuboctahedra with superimposed calculated co-ordination numbers from the EXAFS for the 20 eq wt% Pt/BC and 20 wt% Pt/C against average particle size as suggested by TEM. Error bars indicate s.d. of TEM particle size distribution and confidence intervals from EXAFS fit. Shape models adapted from Glasner and Frenkel48.

The co-ordination numbers N1…4 for the two supports are within the error margins of the fits and, therefore, suggest very similar Pt particle sizes and shapes on both supports. N1 is often used to deduce particle sizes40. Comparing N1 with the expectation values for cuboctahedra and icosahedra shows good agreement with the TEM derived particle sizes for both catalysts.

Particle shape has a stronger influence on more distant platinum shells32. N2 and N3, however, do not lend themselves to further analysis in our case. The differences between icosahedral and cuboctahedral geometries are too small relative to the precision of our fitted values, which is in part inherently limited by the particle size distribution. For this reason, we have abstained from using the method described by Jentys48, which relies on the ratio of N3 to N1 to deduce particle size and shape. The analysis of N4, however, is instructive due to the strong shape sensitivity of N4 for icosahedra and cuboctahedra. The N4 values of both catalysts agree better with a cuboctahedal shape model, suggesting similar exposure of Pt(001) and Pt(111) facets on both supports. Consequently, EXAFS suggests even stronger than TEM that sample averaged particle sizes and shapes are very similar for the Pt/BC and Pt/C catalysts.

Electronic metal-support interaction

As there is no significant change in catalyst size, shape and lattice constant, it is tempting to attribute the significant changes in ORR activity to electronic effects. The Pt 4f spectrum shifts to higher binding energies relative to the C 1 s core levels for Pt/BC (Fig. 2a). Following Lewara et al.17, this might indicate a possible alloy formation with boron or a change in charge transfer between Pt and the support material. There is no evidence of alloy formation in the B 1s XPS (Supplementary Fig. 9). The B 1s peak does not shift, and a model considering only B–B, B–C and B–O bonds is in perfect agreement with the observed spectra. The very similar Pt lattice constants obtained from EXAFS (Table 2) provide further evidence for pure Pt particles. The Pt 4f binding energy shift is, therefore, assigned to purely electronic effects.

It is interesting to note that similar electronic effects have been observed for multiwall carbon nanotubes by Ma et al.49 who find a similar but smaller shift of the Pt 4f core levels. These carbons typically show a work function ∼0.3–0.5 eV different from graphite50. It is, therefore, likely that the measured shift in the Pt 4f core levels are a direct result of changes in the support electronic structure.

Generally, charge is transferred to equilibrate the respective Fermi levels when support and Pt nanoparticle contact. This is qualitatively shown in Fig. 2b. Amongst other factors, the magnitude of the expected charge transfer will depend on the electronic properties of the support material. When changing the support (in this case from C to BC) the extent of this charge transfer changes, resulting in changes in the valence manifolds of the supported catalyst51 and/or support52. This change in electron occupancy can be probed using relative shifts of core levels on either side of the interface52.

By aligning the C(sp2) 1s levels for Pt/C and Pt/BC to exclude other effects, a shift in the Pt 4f peak reflects changes in valence state occupancy across the interface as a result of the changing support material, but might also be influenced to some degree by varying final state effects52. The reduction of the difference between Pt 4f and C(sp2) 1 s core levels by ∼0.6 eV shown in Fig. 2, therefore, indicates an increase of Pt 4f and/or decrease of C 1 s core level binding energies due to larger electron transfer into Pt under UHV conditions, strongly suggesting that the improved ORR activity and stability originates from electronic metal-support interactions.

Charge transfer and d-band occupancy

In principle, one should be able to correlate the sign and magnitude of the relative core level shift with the electronic structure of the respective support materials. There is, however, considerable uncertainty around the electronic properties of the materials reported in the literature. For example, the work function of carbons is usually around 5 eV, but varies as a function of surface termination53. Further, the band structure of boron carbides is sensitive to the local stoichiometry of samples, and the Fermi level depends on the type/degree of doping. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the support material is a composite containing a significant phase fraction of graphitic carbon although we expect the phase fraction on the surface to be significantly smaller than for the bulk support materials due to the aggressive pre-treatment in nitric acid.

Regardless, stronger electron transfer should occur from B4C (typical work function ∼4–4.5 eV (ref. 54)) to Pt (typical work function ∼5.5 eV (ref. 55)) than from C (typical work function ∼5 eV (ref. 53)) to equilibrate the respective Fermi levels as illustrated in Fig. 2b and in agreement with the metal-support interaction suggested by XPS under UHV conditions.

The situation in electrochemical environment, however, is more complex. The in situ XANES spectra shown in Fig. 2c clearly shows an increased hole density in the Pt d-band manifold when particles are supported on BC (that is, more positively charged particles). This apparent contradiction can be resolved by realising that in situ XANES probes a charged interface under potentiostatic control, while ex situ XPS necessarily probes the catalyst under overall neutrality. Because work function and potential of zero charge (pzc) are proportional to each other56, the smaller support work function of the BC-based catalysts will cause a negative shift of the pzc and, hence, a more positively charged Pt/BC catalyst if held at the same potential as the Pt/C catalyst in the same aqueous electrolyte. Finally, it is noteworthy that the support-induced decrease in d-band filling seen for Pt/BC is reminiscent of electronic effects seen for highly active Pt-alloys57.

Comparison of ORR activity with benchmark data

The trends in ORR kinetic activities (Fig. 3, Table 3) are not only a function of support material. Particle size effects are likewise relevant. The conventional interpretation58 in terms of changing surface fractions of Pt(100) and Pt(111), which show different activity for ORR59, has recently been challenged over the relevant particle size range40. However, they are known to significantly impact the results from RDE measurements if the standard protocols and data treatment used here are followed.

Figure 6, therefore, compares surface area specific activity of the Pt/C and Pt/BC catalysts with benchmark data from Garsany et al.44,45 Note that the data from Garsany et al. was corrected for temperature from 30 to 25 °C following a suggestion by Neyerlin et al.60 and to account for the different definition of specific activity used by Garsany et al. (Supplementary Table 3). Our results for the benchmark Pt/C catalysts are in good agreement with the literature data attesting to the quality of our films and robustness of experimental procedures. As already mentioned, the 10 wt% Pt/C catalyst does not lend itself as a benchmark for our purposes due to the significantly smaller particle size and considerable experimental scatter.

The Pt/BC catalysts broadly follow a similar particle size dependence but with overall ∼50% higher surface area specific activity at 0.9 V versus RHE. The increase of surface area specific current density is significantly larger than the expected experimental scatter indicated as grey areas. We, therefore, conclude that purely electronic equilibration between support and catalyst has a bearing on ORR activity of Pt nanoparticles. This is particularly interesting if one considers that the effective charge screening of metals should completely screen the charge redistribution due to Fermi level equilibration between catalyst and support a few atomic distances away from the contact interface61,62,63. Hence, one would not directly expect a pronounced electronic effect on large parts of the more than 20 Å thick Pt particles.

Durability

Figure 4 shows the degradation of ECSA over 6,000 cycles for the 40 eq. wt% Pt/BC and the 40 wt% Pt/C catalyst. The voltage range was selected to promote platinum dissolution and/or agglomeration over support corrosion64. There is a significantly larger rate of ECSA loss for Pt/C after some initial cycles. The consequences of the logarithmic dependence seen in Fig. 4 are worth highlighting. Due to the 1/3 reduction in loss rate per decade, the Pt/BC catalyst retains more than 90% ECSA for about 2,000 cycles, while the Pt/C catalyst shows a 10% loss in surface area already after about 200 cycles.

Since particle sizes and shapes of both catalysts are initially similar, this cannot be due to a more stable particle size as starting point. Hence, the results suggest that the stronger electronic metal-support interaction between Pt and the BC support leads to a reduction in platinum dissolution and/or agglomeration. The ORR activities of the cycled catalysts reported in Table 4 suggest that mostly Pt agglomeration is inhibited for Pt/BC relative to the Pt/C catalyst. While the relative loss of mass specific ORR activity after 6,000 cycles is in line with the loss of ECSA for Pt/BC, Pt/C shows an increase in surface specific and kinetic activity after cycling. This increase in surface specific activity and simultaneous loss in mass activity is a clear indication of increasing Pt particle sizes on the Pt/C support. CO stripping voltammetry (Supplementary Fig. 8) provides further evidence for increased Pt agglomeration on the cycled Pt/C. The pre-peak that is observed for both pristine catalysts has been attributed previously to Pt agglomerates65. This pre-peak feature increases for the cycled Pt/C catalyst while it disappears for the cycled Pt/BC catalyst, indicating increased particle agglomeration for cycled Pt/C.

We have argued above that a stronger dipole field is established at the Pt/BC interface relative to Pt/C, which is corroborated by XPS. This stronger dipole interaction likely reduces the mobility of Pt nanoparticles mitigating agglomeration. A similar effect is seen on carbon supports where the rate of platinum nanoparticle agglomeration is seen to reduce when carbon supports are modified with nitrogen and oxygen containing functional groups that strongly interact with nanoparticles66,67.

Likewise, it suggests that Pt nanoparticles can adopt a lower energy state on BC, which, in principle, should mitigate dissolution. The CVs in Fig. 3b support this interpretation. The oxidation/reduction features of Pt/BC are slightly shifted to more positive potentials relative to Pt/C. Hence, the catalyst might be slightly less prone to surface oxidation/reduction and associated anodic and cathodic Pt dissolution with beneficial implications for cycle stability in this potential range.

Methods

Catalyst preparation

As received B4C (NaBond Technologies Co., Ltd.) was stirred in conc. nitric acid (Kimix Chemicals and Lab Supplies cc.) at room temperature for 8 h. Organo-metallic chemical deposition was used to deposit platinum onto the treated B4C to prepare 10, 20 and 40 eq. wt% Pt/BC, where the eq. wt % was calculated from surface areas calculated from nitrogen physisorption using a TriStar II 3,020 (Micrometrics) and interpreted using BET theory. The catalyst deposition was carried out using platinum acetoacetate (Sigma Aldrich) at 350 °C under an argon atmosphere68,69. As-received Pt/C catalysts from Alfa Aesar (HiSpec 2000, 3000, 4000) were used as a commercial standard for electrochemical activities.

Ex situ catalyst physical characterization

The prepared support material was characterized by nitrogen physisorption, analysed using BET theory (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation TriStar II), to determine the support surface area. XRD measurements were carried out on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with a Cu Kα radiation source operating at 40 kV to determine the crystalline phases present in the catalyst. Rietveld refinement on the XRD patterns was completed using Bruker AXS TOPAS software, Version 4.1. TEM was performed on a Tecnai G2 electron microscope operating at 200 kV to determine particle sizes and a Tecnai F20 with a FEG at 200 kV to obtain images shown in Fig. 1. Elemental analyses were carried out by using a Cs probe-corrected JEOL ARM200F (cold-FEG) TEM/STEM operated at 200 kV and equipped with a Gatan GIF spectrometer. EELS data were acquired with an energy dispersion of 0.25 eV per channel. XPS was carried out by Nexus XPS service at Newcastle University using a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha instrument with an Al Kα X-ray source. The supported catalysts were characterized using TEM for Pt particle size using an average of at least 100 particle diameters sampled across three images for each catalyst; particle distances were obtained by measuring the closest neighbouring platinum particle distance for 100 particles across three TEM images for each catalyst. XRD was used to verify the Pt crystallite size, XPS to investigate the binding energies, and ICP-OES (Varian 730-ES) to confirm the Pt loading on the support. Ex situ advanced surface characterisations were completed using X-ray adsorption spectroscopy on the B18 line at the Diamond Light Source to investigate the morphology of Pt on the surface of the support. The Pt L2 and L3 edges (13,273 and 11,564 eV) were measured on beamline B18 at Diamond Light Source which operated with a ring energy 3 GeV and at a current of 300 mA. The monochromator used Si(111) crystals operating in Quick EXAFS (QEXAFS) mode. A total of three spectra were averaged for each sample. The measurements were collected using the ionization chambers in transmission mode at 298 K. Calibration of the monochromator was carried out at both edges using Pt foils. XAS was collected for the 20 wt% Pt/C and 20 eq. wt% Pt/BC catalysts only. These catalysts were prepared using boron nitride to bind pellets of the catalysts, the pellets were then placed under a H2 atmosphere to reduce surface oxides. The absorption spectra were modelled with Demeter by Bruce Ravel using Ifeffit by Matt Newville17 to solve the EXAFS equation for the first four Pt shell co-ordination numbers as described by Frenkel et al.49 The ink formulation for the 20 eq wt% Pt/BC catalysts used for XANES consisted of 228 mg catalyst, 3.42 ml 5 wt% Nafion solution, 7.6 ml ethanol (Sigma Aldrich); a catalyst layer of 91.46 mg was coated onto a Teflon coated carbon base layer.

Catalyst electrochemical characterization

Catalyst inks were prepared for the electrochemical characterization techniques. The Pt/BC catalyst ink consisted of 2.5 mg of the catalyst, 0.5 ml of ethanol (Sigma Aldrich) and 25 μl of 5 wt% Nafion solution. The mixture was sonicated for 30 min and 5 μl was placed on a glassy carbon electrode. The Pt/C catalyst ink consisted of 5 mg of the catalyst, 5 ml of water (Milli-Q 18.2 mΩcm), 1.5 ml isopropanol (Kimix) and 25 μl of 5 wt% Nafion solution. The mixture was sonicated for 30 min and 10 μl was placed on a glassy carbon electrode. Prior to this, the glassy carbon electrode was polished to a mirror finish using 0.1 and 0.05 μm Al2O3 polish (Buehler). The reference electrode used was Hg/HgSO4 with a platinum counter electrode. Cyclic voltammetry was conducted by cycling the potential between 0.05–1.2 V versus RHE with a scan rate of 50 mVs−1 for 50 cycles at room temperature in an oxygen-free 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte solution to electrochemically clean the catalyst surface. The scan rate was then changed to 20 mVs−1 for 5 cycles and the potential cycled between 0.05 and 1.2 V versus RHE at room temperature in an oxygen-free 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte solution. CO stripping was conducted by purging the electrolyte solution with CO for 20 min while holding the potential at 0.1 V versus RHE, argon was then bubbled for 20 min to rid the solution of CO, after which the potential was cycled between 0.05 and 1.2 V versus RHE. The ORR activity was measured by RDE experiments in an O2 saturated 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte (70% Suprapur—Merck) using the anodic scan between 0.05 and 1.2 V versus RHE, with a scan rate of 20 mVs−1 and rotation rate of 1,600 r.p.m. at room temperature. All scans were normalized for ECSA and corrected for ohmic drop measured by impedance spectroscopy and capacitive current in an oxygen-free electrolyte. Error margins were obtained from 2 to 4 repeats for each data point. The catalyst degradation studies were completed by cycling between 0.6 and 1.0 V versus RHE with a scan rate of 50 mVs−1 in 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte solution for 6,000 cycles at room temperature, and periodically reverted to a cyclic voltammogram between 0.05 and 1.2 V versus RHE with a scan rate of 20 mVs−1 to investigate the changes to the HUPD region. The reference electrode used was Hg/HgSO4 with a gold counter electrode. The HUPD region was used for changes in ECSA in this instance. ORR activity and ECSA were reassessed after cycling using RDE and CO stripping following the procedures described above.

Data availability

All data supporting this study are openly available from the University of Southampton repository at http://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/D0067.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Jackson, C. et al. Electronic metal-support interaction enhanced oxygen reduction activity and stability of boron carbide supported platinum. Nat. Commun. 8, 15802 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15802 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Whitesides, G. & Crabtree, G. Don't forget long-term fundamental research in energy. Science 315, 796–798 (2007).

Rabis, A., Rodriguez, P. & Schmidt, T. Electrocatalysis for polymer electrolyte fuel cells: recent achievements and future challenges. ACS Catal. 2, 864–890 (2012).

Stamenkovic, V. et al. Improved oxygen reduction activity on Pt3Ni(111) via increased surface site availability. Science 315, 493–497 (2007).

Gasteiger, H., Kocha, S., Sompalli, B. & Wagner, F. Activity benchmarks and requirements for Pt, Pt-alloy, and non-Pt oxygen reduction catalysts for PEMFCs. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 56, 9–35 (2005).

Nørskov, J., Bligaard, T., Rossmeisl, J. & Christensen, C. Towards the computational design of solid catalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 37–46 (2009).

Marković, N., Schmidt, T., Stamenković, V. & Ross, P. Oxygen reduction reaction on Pt and Pt bimetallic surfaces: a selective review. Fuel Cells 1, 105–116 (2001).

Wang, C., Markovic, N. & Stamenkovic, V. Advanced platinum alloy electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 2, 891–898 (2012).

Stamenkovic, V. et al. Changing the activity of electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction by tuning the surface electronic structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2897–2901 (2006).

Greeley, J. et al. Alloys of platinum and early transition metals as oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 552–556 (2009).

Mayrhofer, K., Hartl, K., Juhart, V. & Arenz, M. Degradation of carbon-supported Pt bimetallic nanoparticles by surface segregation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16348–16349 (2009).

Chen, S., Gasteiger, H., Hayakawa, K., Tada, T. & Shao-Horn, Y. Platinum-alloy cathode catalyst degradation in proton exchange membrane fuel cells: nanometer-scale compositional and morphological changes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A82 (2010).

Strasser, P. et al. Lattice-strain control of the activity in dealloyed core-shell fuel cell catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2, 454–460 (2010).

Escudero-Escribano, M. et al. Tuning the activity of Pt alloy electrocatalysts by means of the lanthanide contraction. Science 352, 73–76 (2016).

Reiser, C. et al. A reverse-current decay mechanism for fuel cells. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 8, A273 (2005).

Huang, S., Ganesan, P. & Popov, B. Titania supported platinum catalyst with high electrocatalytic activity and stability for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 102, 71–77 (2011).

Cheon, J. et al. Intrinsic relationship between enhanced oxygen reduction reaction activity and nanoscale work function of doped carbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8875–8878 (2014).

Lewera, A., Timperman, L., Roguska, A. & Alonso-Vante, N. Metal-support interactions between nanosized Pt and metal oxides (WO3 and TiO2) studied using x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 20153–20159 (2011).

Dulub, O., Hebenstreit, W. & Diebold, U. Imaging cluster surfaces with atomic resolution: the strong metal-support interaction state of Pt supported on TiO2(110). Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3646–3649 (2000).

Xiong, L. & Manthiram, A. Synthesis and characterization of methanol tolerant Pt/TiOx/C nanocomposites for oxygen reduction in direct methanol Fuel Cells. Electrochim. Acta 49, 4163–4170 (2004).

Chen, G., Bare, S. & Mallouk, T. Development of supported bifunctional electrocatalysts for unitized regenerative fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A1092 (2002).

Takasaki, F. et al. Carbon-free Pt electrocatalysts supported on SnO2 for polymer electrolyte fuel cells: electrocatalytic activity and durability. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, B1270 (2011).

Rabis, A. et al. Catalyzed SnO2 thin films: theoretical and experimental insights into fabrication and electrocatalytic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 11292–11302 (2014).

Du, M., Cui, L., Cao, Y. & Bard, A. Mechanoelectrochemical catalysis of the effect of elastic strain on a platinum nanofilm for the ORR exerted by a shape memory alloy substrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7397–7403 (2015).

Nesselberger, M. et al. The effect of particle proximity on the oxygen reduction rate of size-selected platinum clusters. Nat. Mater. 12, 919–924 (2013).

Liu, Y., Kelly, T., Chen, J. & Mustain, W. Metal carbides as alternative electrocatalyst supports. ACS Catal. 3, 1184–1194 (2013).

Antolini, E. & Gonzalez, E. Ceramic materials as supports for low-temperature fuel cell catalysts. Solid State Ion. 180, 746–763 (2009).

Samsonov, G. Boron, Its Compounds And Alloys House of the Academy of Sciences Ukrainian SSR (1960).

Ding, H. & Hihara, L. Electrochemical examinations on the corrosion behavior of boron carbide reinforced aluminum-matrix composites. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, C118 (2011).

Grubb, W. & McKee, D. Boron carbide, a new substrate for fuel cell electrocatalysts. Nature 210, 192–194 (1966).

Lv, H., Peng, T., Wu, P., Pan, M. & Mu, S. Nano-boron carbide supported platinum catalysts with much enhanced methanol oxidation activity and CO tolerance. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 9155 (2012).

O’Connell, K. & Regalbuto, J. High sensitivity silicon slit detectors for 1 nm powder XRD size detection limit. Catal. Lett. 145, 777–783 (2015).

Frenkel, A., Hills, C. & Nuzzo, R. A view from the inside: complexity in the atomic scale ordering of supported metal nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 12689–12703 (2001).

Assumpção, M. et al. Degradation of dipyrone via advanced oxidation processes using a cerium nanostructured electrocatalyst material. Appl. Catal. A: General 462–463, 256–261 (2013).

Fanchini, G., McCauley, J. & Chhowalla, M. Behavior of disordered boron carbide under stress. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 035502 (2006).

Vincent, C., Vincent, H., Mourichoux, H. & Bouix, J. Characterization by XPS and SEM of reactive chemical vapour deposited boron carbide on carbon fibre. J. Mater. Sci. 27, 1892–1900 (1992).

Mérel, P., Tabbal, M., Chaker, M., Moisa, S. & Margot, J. Direct evaluation of the sp3 content in diamond-like-carbon films by XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 136, 105–110 (1998).

Yoshitake, H., Mochizuki, T., Yamazaki, O. & Ota, K. Study of the density of the d-state and structure transformation of Pt fine particles dispersed on carbon electrodes by in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Electroanal. Chem. 361, 229–237 (1993).

Mansour, A., Cook, J. & Sayers, D. Quantitative technique for the determination of the number of unoccupied d-electron states in a platinum catalyst using the L2,3 x-ray absorption edge spectra. J. Phys. Chem. 88, 2330–2334 (1984).

Green, C. & Kucernak, A. Determination of the platinum and ruthenium surface areas in platinum–ruthenium alloy electrocatalysts by underpotential deposition of copper. I. unsupported catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 1036–1047 (2002).

Nesselberger, M. et al. The particle size effect on the oxygen reduction reaction activity of Pt catalysts: influence of electrolyte and relation to single crystal models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 17428–17433 (2011).

Paulus, U., Schmidt, T., Gasteiger, H. & Behm, R. Oxygen reduction on a high-surface area Pt/Vulcan carbon catalyst: a thin-film rotating ring-disk electrode study. J. Electroanal. Chem. 495, 134–145 (2001).

Fabbri, E. et al. The effect of platinum nanoparticle distribution on oxygen electroreduction activity and selectivity. ChemCatChem 6, 1410–1418 (2014).

Mayrhofer, K. et al. Measurement of oxygen reduction activities via the rotating disc electrode method: from Pt model surfaces to carbon-supported high surface area catalysts. Electrochim. Acta 53, 3181–3188 (2008).

Garsany, Y., Singer, I. & Swider-Lyons, K. Impact of film drying procedures on RDE characterization of Pt/VC electrocatalysts. J. Electroanal. Chem. 662, 396–406 (2011).

Garsany, Y., Baturina, O., Swider-Lyons, K. & Kocha, S. Experimental methods for quantifying the activity of platinum electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Anal. Chem. 82, 6321–6328 (2010).

Glasner, D. & Frenkel, A. Geometrical Characteristics of Regular Polyhedra: Application to EXAFS Studies of Nanoclusters. AIP Conference Proceedings 882, 746–748 (2007).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Jentys, A. Estimation of mean size and shape of small metal particles by EXAFS. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1, 4059–4063 (1999).

Ma, J. et al. Spectroelectrochemical probing of the strong interaction between platinum nanoparticles and graphitic domains of carbon. ACS Catal. 3, 1940–1950 (2013).

Liu, P. et al. Thermionic emission and work function of multiwalled carbon nanotube yarns. Phys. Rev. B 73, 235412 (2006).

Wakisaka, M. et al. Electronic structures of Pt-Co and Pt-Ru alloys for CO-tolerant anode catalysts in polymer electrolyte fuel cells studied by EC-XPS. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 23489–23496 (2006).

Mitsuhara, K. et al. Electronic charge transfer between Au nano-particles and TiO2-terminated SrTiO3(001) substrate. Surf. Sci. 604, 548–554 (2010).

Fabish, T. & Hair, M. The dependence of the work function of carbon black on surface acidity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 62, 16–23 (1977).

Du, J. et al. Synthesis of boron carbide nanoflakes via a bamboo-based carbon thermal reduction method. J. Alloys Compd 581, 128–132 (2013).

Haynes, W., Lide, D. & Bruno, T. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics CRC (2012).

Bockris, J. & Argade, S. Work Function of metals and the potential at which they have zero charge in contact with solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 49, 5133–5134 (1968).

Mukerjee, S., Srinivasan, S. & Soriaga, M. P. Role of structural and electronic properties of Pt and Pt alloys on electrocatalysis of oxygen reduction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142, 1409 (1995).

Kinoshita, K. Particle size effects for oxygen reduction on highly dispersed platinum in acid electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 137, 845 (1990).

Markovic, N., Gasteiger, H. & Ross, P. Oxygen reduction on platinum low-index single-crystal surfaces in sulfuric acid solution: rotating ring-Pt(hkl) disk studies. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 3411–3415 (1995).

Neyerlin, K., Gu, W., Jorne, J. & Gasteiger, H. Determination of catalyst unique parameters for the oxygen reduction reaction in a PEMFC. J. Electrochem. Soc. 153, A1955 (2006).

Joyner, R., Pendry, J., Saldin, D. & Tennison, S. Metal-support interactions in heterogeneous catalysis. Surf. Sci. 138, 84–94 (1984).

Tripković, V. et al. Metal oxide-supported platinum overlayers as proton-exchange membrane fuel cell cathodes. ChemCatChem 4, 228–235 (2012).

Jiang, Z. et al. Direct XPS evidence for charge transfer from a reduced rutile TiO2(110) surface to Au clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 12434–12439 (2007).

Wu, J. et al. A review of PEM fuel cell durability: degradation mechanisms and mitigation strategies. J. Power Sources 184, 104–119 (2008).

Maillard, F. et al. Influence of particle agglomeration on the catalytic activity of carbon-supported Pt nanoparticles in CO monolayer oxidation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 385–393 (2005).

Yu, X. & Ye, S. Recent advances in activity and durability enhancement of Pt/C catalytic cathode in PEMFC. J. Power Sources 172, 133–144 (2007).

Zhou, Y. et al. Enhancement of Pt and Pt-alloy fuel cell catalyst activity and durability via nitrogen-modified carbon supports. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1437 (2010).

Naidoo, Q., Naidoo, S., Petrik, L., Nechaev, A. & Ndungu, P. The influence of carbon based supports and the role of synthesis procedures on the formation of platinum and platinum-ruthenium clusters and nanoparticles for the development of highly active fuel cell catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 9459–9469 (2012).

Taylor, S., Fabbri, E., Levecque, P., Schmidt, T. & Conrad, O. The effect of platinum loading and surface morphology on oxygen reduction activity. Electrocatalysis 7, 287–296 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was largely supported by the Royal Society in the form of a Royal Society-Newton Advanced Fellowship (P.L.; grant no. NA140367). C.J. acknowledges the University of Cape Town for financial support through a UCT PhD Mobility Grant. D.K. and G.T.S. thank the EPSRC H2FC SUPERGEN (grant no. EP/J016454/1) for financial support. G.T.S. thanks the HySA/Catalysis Programme for a postdoctoral fellowship. D.K. acknowledges support from STFC (ST/K00171X/1 and ST/N002385/1). We thank Tobias Binninger and Thomas Schmidt from Paul Scherrer Institut for work with D.K. on a theoretical framework of electronic metal-support interactions that predates and informed the experiments. Facilities use was supported by the HySA/Catalysis Centre of Competence (UCT) and the Department of Chemistry (UoS). Additionally, we thank the National EPSRC XPS Users' Service (NEXUS) at Newcastle University, Diamond Light Source, the ‘South of England Analytical Electron Microscope’ supported by EPSRC (EP/K040375/1), and the UCT Electron Microscope Unit for instrument access. Tarek Kollmetz assisted with powder conductivity measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J. and G.T.S. synthesized materials and performed XRD, TEM, XPS and electrochemical characterization; C.J., P.S.W., A.S.L. and D.W.I. performed XAS studies at Diamond; G.T.S. and M.C. performed EELS analyses supported by T.P.; D.K., P.L. and A.E.R. assisted in interpretation of results; C.J. and D.K. co-wrote the manuscript; all authors commented on the manuscript; D.K. conceived the experimental idea whilst being on sabbatical with P.L.’s group.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References (PDF 1246 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, C., Smith, G., Inwood, D. et al. Electronic metal-support interaction enhanced oxygen reduction activity and stability of boron carbide supported platinum. Nat Commun 8, 15802 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15802

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15802

This article is cited by

-

Diversity of platinum-sites at platinum/fullerene interface accelerates alkaline hydrogen evolution

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Elucidating the electronic metal-support interaction enhanced hydrogen evolution activity on Ti3C2Tx MXene basal plane by scanning electrochemical microscopy

Nano Research (2023)

-

Catalytic degradation of organic pollutants for water remediation over Ag nanoparticles immobilized on amine-functionalized metal-organic frameworks

Nano Research (2022)

-

Hierarchical ZrO2@N-doped carbon nano-networks anchored ultrafine Pd nanoparticles for highly efficient catalytic hydrogenation

Science China Chemistry (2022)

-

Galvanic replacement managing direct methanol fuel cells: AgPt nanotubes as a strategy for methanol crossover effect tolerance

Journal of Materials Science (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.