Abstract

Prions induce a fatal neurodegenerative disease in infected host brain based on the refolding and aggregation of the host-encoded prion protein PrPC into PrPSc. Structurally distinct PrPSc conformers can give rise to multiple prion strains. Constrained interactions between PrPC and different PrPSc strains can in turn lead to certain PrPSc (sub)populations being selected for cross-species transmission, or even produce mutation-like events. By contrast, prion strains are generally conserved when transmitted within the same species, or to transgenic mice expressing homologous PrPC. Here, we compare the strain properties of a representative sheep scrapie isolate transmitted to a panel of transgenic mouse lines expressing varying levels of homologous PrPC. While breeding true in mice expressing PrPC at near physiological levels, scrapie prions evolve consistently towards different strain components in mice beyond a certain threshold of PrPC overexpression. Our results support the view that PrPC gene dosage can influence prion evolution on homotypic transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mammalian prions are proteinaceous transmissible pathogens responsible for a broad range of lethal neurodegenerative diseases in animals and humans1, including scrapie in sheep and goats, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), cervid chronic wasting disease and human Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD). Prions are primarily formed of macromolecular assemblies of PrPSc, a beta-sheet enriched conformer of the ubiquitously expressed, host-encoded prion protein PrPC (ref. 2). During replication, PrPSc is thought to recruit and convert PrPC molecules through a seeded-polymerization process3,4, leading to PrPSc aggregates deposition in the brain and sometimes in extraneural tissues and bodily fluids of the infected individuals5,6,7,8.

Multiple strains of prions can be recognized in a given host species, causing disease with specific phenotypic traits, such as time course to disease, neuropathological features, PrPSc biochemical properties and tissue or cell tropism9,10,11,12. There is compelling evidence that prion strain diversity reflects differences in PrPSc conformations, at the level of the tertiary and/or quaternary structure4. Although a dominant PrPSc conformation appears to determine the strain phenotype, there is evidence that differing, PrPSc three-dimensional conformations,—beyond the intrinsic diversity of PrPSc physicochemical states13,14,15,16—, may be co- propagated. This could reflect the presence of subdominant prion strains17,18,19,20 or a ‘quasi-species’ phenomenon11,21, as documented for viral pathogens. Interspecies transmission of prions is usually limited by a species or transmission barrier11. However, such cross-species transmission events can occur, as exemplified by the emergence of variant CJD in the human population dietary exposed to BSE prions1. Based mostly on PrP transgenic mouse models data22, the conformational selection model11,23 posits that the transmission barrier stringency depends on the degree of steric compatibility between PrPSc structure(s) present in the infecting prion and host PrPC conformational landscape. A high transmission barrier can lead to mutation-like events, generating prion variant(s) with new biological strain properties24,25,26,27,28. Oppositely, homotypic transmissions (that is, when the host expresses the same PrP amino acid sequence as the infecting prion) generally result in apparent lack of transmission barrier and conservation of strain type24,29,30,31. However, there are few, remarkable examples of abrupt, phenotypic change during homotypic prion transmission: a faster replicating strain was shown to emerge from serial propagation of laboratory mouse 87A prions on high dose-inoculated, wild-type mice32. More recently, experimental transmission of variant CJD cases to mice transgenic for human PrP occasionally produced a sporadic-like phenotype31. Finally, transmission of H-type atypical BSE prions to bovine PrP transgenic led to the emergence of prions with different strain phenotypes33,34.

Here, we examined the outcome of prion homotypic transmissions by comparing the transmission pattern of sheep prion isolates on multiple lines of transgenic mice expressing varying levels of the VRQ allele of ovine PrP, associated with the highest susceptibility to scrapie35. We show that either faithful or divergent prion strain propagation occurred, this being critically controlled by PrPC gene dosage in the transgenic mouse brain. Our findings reveal a new facet of the biology of prions, with both practical and theoretical implications.

Results

Discordant strain phenotypes on PrPC overexpresser mice

We transmitted by intracerebral route a hundred sheep isolates, with diverse geographical origin and proteinase K-resistant PrPSc (PrPres) signature, to tg301+/− and tg338 mice expressing VRQ ovine PrPC at a level ∼8-fold that in sheep brain. tg301+/− and tg338 are independent lines expressing the same construct tg3 at the hetero- and homozygous state, respectively36. tg3 consists of a 125 kb piece of sheep DNA including regulatory sequences insert into a BAC vector, leading to a transgene expression pattern mimicking that of the endogenous gene37. Many isolates behaved as commonly observed when donor and host PrP sequences are homologous; that is, the incubation durations (ID) did not differ, or only showed moderate variations, between primary and subsequent passages. The PrPres molecular profile in the brain was uniform among the inoculated mice, regardless of whether the donor sheep was of VRQ/VRQ genotype or not9,30,36. However, about half of the isolates from various genotypes, including several isolates sourced from an INRA experimental sheep flock where scrapie was highly prevalent (Langlade35), did not conform to this pattern. The data gathered in Fig. 1, obtained with the LAN404 isolate, illustrate the complex transmission pattern that can be seen with such isolates. On primary transmission, the ID averaged 200 days on both mouse lines, and was relatively homogenous, that is, 100% attack rate with SEM averaging 10 days (>10 independent inoculation experiments involving either tg301+/− or tg338 mice; Fig. 1a,b) Systematic examination for PrPres content of the brains from terminally diseased tg301+/− animals revealed unexpected molecular profiles. Nearly all mice exhibited a PrPres signature clearly distinct from that in the donor sheep brain, with unglycosylated fragments migrating around 19 kDa (PrPres 19K). A few mice—typically 1 out of 10—accumulated aglycosyl PrPres sizing ∼21K (PrPres 21K), as in the isolate (Fig. 1a–c). Secondary transmissions using individual tg301+/− brains to the tg301+/− or tg338 lines consistently led to a marked shortening of the mean ID. Within at most two subpassages, the agent appeared to segregate under two readily distinguishable phenotypes, which we designated LA19K (mean ID ∼125–130 days and PrPres 19K type) and LA21K fast (mean ID∼60 days and PrPres 21K type). Serial transmission of LAN404 to tg338 mice led to similar findings. In the experiment presented in Fig. 1b, all diseased mice showed a 19K PrPres signature in the brain. Yet individual brain-to-brain subpassaging revealed that for one of them (no. 9) the PrPres signature had shifted from 19K (Fig. 1c) to 21K type, and the mean ID shortened to ∼60 days within two subpassages. By contrast the ID stayed ∼130 days in the other passage series. This suggested that, in this mouse, one agent had outcompeted the other due to a much faster replication. Indeed, when subpassaging was performed using homogenates prepared from several brains, an agent with either LA21K fast or LA19K phenotype was propagated depending on whether mouse no. 9 was included in the pool or not (Fig. 1b). Thus, subpassaging LAN404 using brain pools from inoculated mice would have produced truncated information.

(a) Serial transmission of LAN404 primary, sheep scrapie isolate to tg301+/− mice and (b) to tg338 mice. Results of a representative experiment are shown. Blue and red colours are used to indicate the segregation of LA19K and LA21K fast phenotypes, respectively. (c) PrPres electrophoretic patterns in the donor sheep and in tg338 and tg301+/− mouse brains following primary infection with LAN404 scrapie isolate and subsequent passage. (d) PrPres deposition pattern in the brain of tg338 mice infected with LA19K or LA21K fast prions. Representative histoblots of antero-posterior coronal brain sections at the level of the septum (i), hippocampus (ii), midbrain (iii) and brainstem (iv). In LA21K fast-infected mice, PrPres deposited specifically in the septum, in the corpus callosum, and in certain raphe nuclei of the brainstem. In LA19K-infected mice, PrPres deposits were finer and specifically detected in the caudate putamen, dorsal and posterior thalamic nuclei. Scale bar, 1 mm.

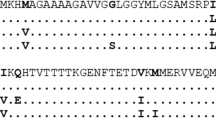

Strain divergence is not due to a PrPC sequence mismatch

The LA21K fast and LA19K strain phenotypes turned out to be fairly stable. Both strains could be propagated on tg338 mice with no further change for up to 7 brain-to-brain subpassages, without the need of biological cloning by endpoint dilution. The clinical course was aggressive in LA21K fast-infected mice, in which hyperexcitability, hyperaesthesy, waddling and rolling gait dominated. In marked contrast, lethargy and hindlimb paresis dominated in LA19K-infected mice and the clinical course evolved at a slower pace. LA21K fast and LA19K strain phenotypes also differed with regard to PrPres regional distribution within the brain, as assessed by histoblot on adjacent coronal sections (Fig. 1d). On the whole, our results were intriguingly reminiscent of the well-documented observation of dual strain evolution on cross-species transmission of transmissible mink encephalopathy to hamster. Such transmission leads to the emergence of two distinct, stable strains, hyper and drowsy, the phenotypic traits of which are similar to LA21K fast and LA19K, respectively19,38,39. We thus rechecked the transgene sequence to exclude the possibility that the isolation of LA21K fast and LA19K prions from LAN404 isolate transmission to transgenic mice resulted from a mismatch between host and donor PrP coding sequences. No difference was found between mouse and donor sheep DNAs, implying that the transmission was definitely homotypic. Therefore, the question arose as to what kind of selection pressures were enabling the sheep scrapie agent to adapt to its new, yet PrP homologous host.

A dual cause for strain divergence in overexpresser mice

We asked whether the emergence of the LA21K fast and LA19K strain components occurred during the propagation in the transgenic mice and/or reflected a pre-existing diversity in the sheep scrapie isolate. To investigate whether LA21K fast prions could pre-exist in LAN404 isolate, we challenged intracerebrally tg338 mice with LAN404 brain homogenate spiked with serial 10-fold dilutions of LA21K fast prions (Fig. 2a). The result was a dramatic shortening of the mean ID, even at endpoint infectious titres of LA21K fast (∼120 instead of ∼200 days for unspiked homogenate (Fig. 1b). As a consequence, LA21K fast prions are unlikely to pre-exist in the sheep scrapie isolate (compare Fig. 1a,b).

(a) Inoculation with serial tenfold dilutions of tg338-passaged LA21K fast brain material spiked (squares) or not (diamonds) in LAN404 sheep brain homogenate. The resulting curves are superimposable. (b) Inoculation with serial tenfold dilutions of LAN404 sheep (square) or tg338-passaged LA19K brain material (circles). Blue and red colours indicate presence of 19K and 21K fast prions, respectively. Grey colour indicates a 21K PrPres profile. The number of mice accumulating 19K and 21K PrPres decreases and increases with dilution, respectively. (n=6 mice were inoculated per dilution).

We next reasoned that, should LAN404 isolate be populated by more than one strain component, diluting the inoculum might be a means to eliminate one of them. Figure 2b shows the individual ID and brain PrPres signatures observed on tg338 mice inoculated with serial dilutions of LAN404 sheep brain homogenate. Remarkably, the more diluted the inoculum, the higher the proportion of individuals with a prominent 21K-type signature, up to 100% (6/6) at the 10−3 dilution. Comparing this dose/ID curve with that obtained with stabilized LA19K prions (three passages on tg338 mice, Fig. 2b) allowed us to calculate that the agent predominant in the original LAN404 isolate had a doubling time about 3-fold higher than LA19K prions. Altogether these data supported the view that LA19K agent is not created de novo on propagation in the overexpresser mice but instead pre-exists in the donor sheep isolate as a minor component, the replication of which is strongly favored in such mice. We also performed a subpassage from individual mice inoculated with 103-diluted LAN404 brain material, culled at terminal stage of disease (>500 days post-inoculation, that is more than 400 days than ID of LA21K fast prions at endpoint dilution), all showing a 21K PrPres signature in their brains (Fig. 2b). As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1, the outcome in tg338 reporter mice was found to depend on the donor brain: either a long ID (∼130 days) with 21K PrPres in most mice and 19K PrPres in some mice, or a short ID (∼75 days) with 21K PrPres in all mice. In addition, the 21K PrPres molecular profiles as well as the deposition pattern in the brain noticeably differed among these two groups of mice. These results support the view that LAN404 sheep scrapie agent can replicate in high expresser mice, and that LA21K fast is a mutant emerging in a stochastic manner within one or two passages.

To summarize, the dual strain evolution observed on both overexpresser lines appears to involve two well distinct mechanisms: (i) preferential selection of an agent present in the donor sheep brain as a subdominant component; (ii) stochastic emergence of a variant that ineluctably outcompetes every other component due to its much greater replication efficiency.

PrPC gene dosage determines the divergent strain evolution

We next wondered whether or not the same phenomena would occur on transmission to an enlarged panel of lines all expressing the VRQ allotype, though from various transgene constructs (tg1, tg2 and tg3), and at variable levels36. On including the tg301+/− and tg338 mice, the panel was comprised of 8 independent lines and 10 different genotypes, and the PrPC expression level ranged from ∼1.2-fold to ≥10-fold that in sheep brain (Table 1). The results obtained after primary transmission of LAN404 are summarized in Fig. 3a. All the lines challenged intracerebrally with LAN404 developed clinical disease at 100% attack rate. There was an inverse correlation between the mean ID and PrPC expression levels, as previously found on transmission of a fast field scrapie isolate to this same mouse panel36.

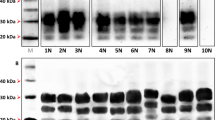

(a) Transmission of LAN404 to transgenic mouse lines expressing the VRQ allele of ovine PrPC at varying levels (expressed as x-fold that in sheep brain). Segmented circles are used to indicate the proportion of mice with 19K (blue) or 21K PrPres signature (grey) in their brains. A double circle is used to indicate the proportion of mice with mixed signature. (b) Representative western blots showing PrPres glycopattern in the different mouse lines (the respective PrPC expression levels are indicated). Mixed 21K and 19K signatures are seen in intermediate expresser mice (right two panels). (c) Histoblots of representative sections at the level of the hippocampus. The PrPres deposition patterns in high and low (left two panels) expresser mice are distinct. Scale bar, 1 mm.

Most strikingly, the brain PrPres profiles in the diseased mice differed among the lines and such a variation appeared to be primarily linked to the PrP expression level. Unlike that observed in overexpresser mice (≥8-fold), the 19K PrPres signature was detected in none of the mice with an expression level below 3.5-fold (five independent lines, three different constructs); all these mice exhibited a 21K type signature in their brain, reminiscent of LAN404 and more enriched in unglycosylated species than LA21K fast in tg338 mice (Fig. 1c). At intermediate expression levels (3.5- to 4-fold), mixed 19K and 21K PrPres profiles were found in a notable proportion of mice (Fig. 3). This PrPres signature discrepancy was observed in mouse lines harbouring the same (tg3) construct: 21K in tg335+/− low expresser mice, 19K in nearly all tg338 and tg301+/− high expresser mice, and a combination of both in tg328+/− and tg338+/−, intermediate expresser mice. Therefore, the transgene structure, and thus its expression pattern including in peripheral tissues such as spleen, played apparently no crucial, intrinsic role in this phenomenon. We then asked whether and how the phenotypes observed on low expresser mouse lines would evolve on secondary transmission. We performed transmissions from LAN404 primary inoculated, low expresser—tg335+/− and tg143+/−—toward mice of the same line, and in parallel to tg338 mice to see how low expresser mice-passaged agent would behave compared with LAN404 isolate (Fig. 4a). Remarkably, no abrupt shortening of the mean ID occurred when LAN404 was subpassaged on low expresser mice exclusively, and the PrPres profile remained of 21K type uniformly (up to three passages on tg335+/−). On passage to tg338 mice, however, the transmission pattern resembled that seen on LAN404 primary inoculated tg338 and tg301+/− mice (Fig. 1), that is, the 19K PrPres profile prevailed (∼2/3 of the mice), and one additional passage led to the reappearance of either LA19K or LA21K fast uniform phenotypes, depending on whether brain tissue with 19K or 21K PrPres was inoculated (Fig. 4a). Altogether, these results led us to conclude that: (i) mice expressing PrP at a sheep brain-like level do propagate preferentially an agent thereafter designated LA21K, which exhibits features of the original isolate; (ii) the LA19K agent is also able to replicate on low PrPC level mice, however as a ‘hidden’ component; (iii) LA21K fast agent can be re-isolated via transmission from low to high expresser mice.

(a) Serial transmission to low expresser mice and subpassage to high expresser mice (tg338). A phenotype associating 21K PrPres and ID >300 days, designated LA21K (see main text), is maintained along subpassage on low expresser mice. (b) Serial transmission to mice expressing PrPC at intermediate levels. Segmented circles are used to indicate the proportion of mice with LA19K (blue), LA21K (grey) or 21K fast (red) PrPres profiles in their brains. A double circle is used to indicate the proportion of mice with mixed signature. Transmission of 21K PrPres prions propagated on intermediate expresser mice (tg328+/−) to high expresser mice (tg338) enables to rescue both 19K and 21K fast phenotypes.

We also performed serial transmissions within and from ‘intermediate’ expresser mice. The resulting picture was overall consistent with the preceding results. Briefly, subpassages from primary inoculated tg328+/− mice produced either 21K or19K type signatures, depending on whether the secondary inoculated mice were tg328+/− or tg338, respectively. Even after two consecutive subpassages on tg328+/− mice LA19K prions could be rescued and stabilized by using tg338 mice for further passage (Fig. 4b). Essentially similar results were obtained on serial transmissions involving tg338+/− mice (4-fold), which again behaved differently from their homozygous counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 2). These experiments showed that middle expresser mice allow silent propagation of LA19K agent for at least two subpassages.

Three distinct strains can propagate on low expresser mice

As shown above, LA19K component lacked a selective advantage in mouse lines expressing PrPC at levels below 4-fold. However, the question arose of whether such mice would allow a steady propagation of this agent first amplified on overexpresser mice. Brain material from three serial passages of LAN404 isolate on tg338 mice was inoculated to relevant mouse lines (Fig. 5a). Remarkably, the PrPres profiles were uniformly of 19K type in all but the lowest expresser tg335+/− line. The mean ID tended to be briefer compared with unpassaged LAN404 inoculum, this difference increasing with the PrPC expression level (Supplementary Table 1). Such results indicated that, while PrPC overexpression is not a prerequisite for sustained replication of LA19K agent, the ID increases dramatically relative to 21K agent when PrPC expression approaches a physiological level. The observed ‘resurgence’ of 21K PrPres signature in a proportion of tg335+/− mice was likely due to residual 21K agent in LA19K-enriched inoculum. Indeed, when LA19K was biologically cloned on tg338 mice before inoculation to tg335+/− mice, the PrPres profiles were of 19K type exclusively (Fig. 5a).

Since LA21K prions underwent no apparent, abrupt phenotypic change on propagation onto low expresser mice, it was feasible to compare their strain-specific traits with those of the LA21K fast variant emerging on mice expressing PrPC at a ≥3-fold level. Inoculation to tg143+/− and tg335+/− mice of LA21K fast prions (four passages on tg338 mice) produced mean IDs of 132±2 days and 140±5 days, respectively (Fig. 5b), thus markedly shorter than for LAN404 homogenate primary or secondary inoculated to the same lines (320–350 days; see Fig. 4). Further confirming that LA21K and LA21K fast are truly distinct strains, their glycoform-profiles were clearly differentiable in the brain of these mice, with LA21K being enriched in diglycosylated forms, as in the LAN404 primary isolate (Fig. 6).

Ratio of diglycosylated to monoglycosylated PrPres species in the brains of tg335+/− (square), tg211+/− (triangle) and tg143+/− (circle) mice following transmission of LA21K fast (red) or LA21K (grey) prions (data plotted as means±s.e.m.); n=5 mice analysed per prion strain and mouse line). LA21K and LA21K fast prions show distinct glycoform patterns, with little variation depending on the mouse line.

Inoculation to low expresser mice of LA21K fast and LA19K prions from early passages on high expresser mice produced results essentially similar to those described above (Supplementary Fig. 3). Finally, histoblotting analysis revealed distinct features for the three identified agents (Fig. 7). Altogether these results clearly show that not less than three distinct prion strains, all derived from the same isolate, could be propagated on low expresser mice.

Representative histoblots at the level of the hippocampus are shown. In LA21K fast-infected mice, there is a widespread and granular-like deposition of PrPres in most brains areas, including the cortex and corpus callosum. The protein was not detected in the habenula. In LA21K-infected mice, PrPres was not detected in the cortex and corpus callosum, while present in the habenula, thalamus and hypothalamus. In LA19K-infected mice, there is a preferential accumulation of fine PrPres deposits in the thalamus, oriens layer of the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Scale bar, 1 mm.

Discussion

In this study we provide experimental evidence that on homotypic transmission of a natural prion source to transgenic mice, different strains may be propagated depending on the PrPC gene dosage in the recipient line. Indeed, we show that serial brain-to-brain transmission of a representative, sheep scrapie isolate to a panel of ten transgenic mouse lines that expressed the same ovine PrPVRQ allotype at a varying level, 1- to 10-fold that in sheep brain, produced a pattern of unexpected complexity, involving no less than three distinct, bona fide prion strains. A mechanism of strain selection based on PrPC expression level is proposed. Aside obvious implications regarding the characterization of natural prions by transmission to transgenic mice, our findings lead us to hypothesize that variation in the neuronal PrPC expression level might contribute to the intriguing phenomenon of strain- specific, neuronal targeting exhibited by mammalian prions.

The somewhat intricate data presented here can be summarized as depicted in Fig. 8. Transmission of LAN404 isolate to high expresser mice led rapidly—as soon as at first passage—to the emergence of two obviously different strain components that proved to be fairly stable phenotypically on subsequent, iterative passage. The most parsimonious interpretation of the experiments subsequently carried out is that this dual evolution was determined by two distinctive events: (i) the preferential amplification of an agent designated LA19K, pre-existing in the brain tissue of the donor sheep as a subdominant component; (ii) the stochastic, de novo emergence in a minority of mice of an agent called LA21K fast, a ‘mutant’ from the 21K strain component predominating in the donor sheep brain, which propagates even faster than LA19K agent. Strikingly, none of these agents emerged when the same isolate was serially passaged onto mouse lines expressing PrPC at a sheep-like level or up 3-fold higher. Instead, such mice appeared to stably propagate an agent termed LA21K, with molecular properties of the original isolate, and from which it was possible to re-isolate the LA19K and LA21K fast components by transmission to high expresser mice. Nevertheless, transmission of LA19K and LA21K fast propagated on high expresser mice to low expresser ones resulted in faithful and steady propagation of both these agents.

A schematic overview of the pattern observed upon homotypic transmission of this VRQ/VRQ sheep isolate to transgenic mice expressing same allele of ovine PRPC is shown. High expresser mice (8-fold level; expressed as x-fold that in sheep brain) and low expresser mice (≤3-fold level) are represented in grey and white, respectively. On high expresser lines, 19K prions (blue) subdominant in the donor sheep brain are preferentially propagated over 21K prions. 21K prions occasionally mutate to 21K fast prions (red). On lines expressing PrPC at a physiological or ≤3-fold level, 21K prions (black) are preferentially propagated over 19K prions, as assumed to be the case in the donor sheep. Overall, transmission of LAN404 isolate led to the individualization of three strain components, LA19K, LA21K and LA21K fast, each of them being able to replicate—overtly or silently—on both high and low expresser lines. Overt propagation of LA21K prions in high expresser mice can be observed on inoculating diluted, primary inoculum so as to eliminate the subdominant LA19K component.

The abrupt LA21K to LA19K strain shift following transmission to mice expressing PrPC at supraphysiological levels implies that an authentic adaptation process had been taking place, mimicking what can occur after across species transmission24,25,26,27,28,39. In the present case, however, neither a divergence between the coding sequences of donor and host PrPC, nor an effect of the transgene organization could be incriminated. Consequently, the transgene dosage itself has to be considered as the key determinant. How could the availability in PrPC substrate at a cell or tissue level variably affect prion propagation efficiency in a strain-dependent manner? Overexpression might favour one strain over another by causing extra- localization of PrPC in specific brain region(s). This is unlikely since a BAC construct, known to lead to an integration-site independent and copy-number related level of expression36,37, was used in both high and low expresser tg3 lines. Moreover, histoblotting analyses of uninfected mice harbouring the tg3 construct (Supplementary Fig. 4) revealed a widespread distribution of PrPC in the brain whatever the expression level, without obvious qualitative differences, notably in areas of preferential PrPSc accumulation for either one or the strains. Hence the ‘ectopic’ explanation, that is, a competitive advantage in specific neural cell populations to which overexpression would give access, seems unlikely. Saturation of a binding partner is an alternative possibility that cannot be ruled out. According to the literature, a number of cellular factors can promote the replication efficiency to a variable extent depending on the strain40,41,42. Assuming that such a factor is both physically interacting with PrPC and in limiting concentration, its exhaustion in overexpressing mice would afford a competitive advantage to the strain that is less dependent on it. We do favour, however, another mechanistic explanation involving a kinetic competition during prion fibres formation. How can a strain A predominate over a strain B only beyond a certain threshold of PrPC concentration, without having an all-or-none phenotype? This can be mathematically modelled assuming that: (i) during the templating process, oligomeric PrPC is incorporated according to a concerted process (discussed in ref. 42); (ii) the number of protomers n within the oligomeric subunits is a strain feature, with nA>nB (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Note 1).

Unlike LA19K, LA21K fast appears to occasionally emerge as a mutant of the parental strain LA21K during the propagation in mice. The tendency of slow replicating strains to generate a faster mutant is documented for mammalian as well as yeast prions25,32,43. Why such a mutational event would be enhanced in overexpresser mice is uncertain, a possible explanation being that the shift toward the LA21K fast prion folding pathway involves an interaction with PrPC molecules in a rare or transient conformational state.

To be underlined, the complex transmission pattern seen with LAN404 isolate is not a unique feature. On the contrary, the 19K/21K phenotype divergence on high/low expresser mice was observed with 18 out of 20 geographically unrelated isolates examined purposely. Moreover, LAN404 is the strain prototype of the group found to be the most abundant among five major groups delineated following transmission of a large panel of natural sheep typical scrapie isolates9). The nearly constant co- propagation of LA21K and LA19K agents thus suggests an ontogenic link, rather than a simple strain mixing20. No LA21K prion was found to emerge on serial propagation of biologically cloned LA19K. Conversely, LA21K could be the parent strain, with an inherent propensity to generate 19K prions, yet as a silent component in sheep brain. In contrast, the LA21K mutation into LA21K fast variant would have to be a rare event in natural conditions—at least on VRQ/VRQ sheep. In any case, it is of interest that the combined propagation of a single isolate on low and high expresser mice recapitulated part of the natural scrapie strains variation as documented by transmission to high expresser mice9. In particular, LA19K and the reference scrapie strain CH1641 exhibit identical features44. Thus panels of transgenic mice harbouring various PrPC levels might represent a relevant tool in an attempt to learn more about the determinism underlying the diversity and evolution of natural prions. Incidentally, there is frequent co-occurrence of 21K/19K PrPres signatures in the brain of human individuals affected by sporadic CJD whose strainness is still debated18,45,46. Our findings might contribute to clarify this issue. A further, methodological implication of our findings is that subpassaging of natural isolates using brain pools of infected mice—not an unusual practice in the field—should be avoided as it can produce truncated or misleading information.

The molecular basis of the strain-specific targeting of brain regions by prions remains unexplained to date. A commonly, long-invoked hypothesis, that is, the selective permissiveness of neural cell subpopulations, has been recently supported by elegant studies showing that the spectrum of infectible cell lines and subclones encoding the same PrPC allele can markedly differ from one strain to another47. Various, still conjectural mechanisms have been advanced to account for such a strain discriminative, cell autonomous permissiveness, involving: (i) the array of available convertible PrPC isoforms notably in terms of glycoform ratio48,49,50; (ii) the availability of co-factors influencing the replication efficiency40,41,42,51; (iii) the rate of PrPSc processing and clearance52,53; (iv) the polymer fragmenting activity resulting in new seeds54,55. Our findings lead us to conjecture that the steady state level of PrPC might contribute to the differential permissiveness of specific neural subpopulations to prion (sub)strains, possibly on a replication dynamics basis. Indeed, the expression of PrPC actually varies depending on the brain structure48,56,57,58,59. A marked disparity in the PrPC steady state level (up to ≥10-fold) exists among neuronal subpopulations, the primary cause being seemingly the rate of degradation rather than the rate of synthesis57. As a very preliminary step to test the pathophysiological relevance of this novel notion, we examined the regional distribution of PrPres in diseased mice infected with LA19K prions (Supplementary Fig. 6). Although PrPres in the whole brain was 19K type, essentially 21K PrPres was found to accumulate in the brainstem, where PrPC is expressed at lower levels48. Moreover, our ongoing studies suggest that the PrPC expression level in extraneural compared with nervous tissues might contribute to the selective neurotropism manifested by certain prions.

Methods

Ethics

Animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with ECC and EU directives 86/009 and 2010/63 and were subsequently approved by the local ethics committee of the author’s institution (Comethea; permit number 12/034).

Transgenic mouse lines

The constructs, the mouse lines and their respective ovine PrPC expression level (VRQ allele) have been described36,60,61, and are listed in Table 1. Female, 6–8 week-old individuals were used were used for the prion transmission experiments.

Prion transmission

To avoid any cross-contamination, a strict protocol based on the use of disposable equipment and preparation of all inocula in a class II microbiological cabinet was followed. Brain material (brainstem) from sheep terminally affected with natural scrapie36 sources was used as prion sources. The tissue extract was prepared as 10% w/v homogenate in 5% w/v glucose with a Hybaid or Precellys rybolyzer (Ozyme, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) for inoculation to ovine PrP transgenic mice. Twenty microliters were inoculated intracerebrally in the right hemisphere to groups of individually identified mice, at the level of the parietal cortex. For subsequent passage, mouse brains were collected with sterile, disposable tools, homogenized at 20% w/v in 5% glucose and reinoculated intracerebrally at 10% w/v. For endpoint titration, starting from 10% w/v brain homogenate (undiluted material), serial 10-fold dilutions of brain homogenates were prepared extemporaneously in 5% w/v glucose containing 5% w/v bovine serum albumin. Twenty microliters of each dilution were inoculated into recipient mice by intracerebral route. Animals were supervised daily for the prion disease development. Animals at terminal stage of disease were euthanized. Their brains were analysed for proteinase K-resistant PrPSc (PrPres) content.

Western blot

Brain homogenates (typically 200 μl of 10% brain homogenate) were digested for 1 h with PK (final concentration 10 μg˙ml) at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped with 4 mM PMSF. After addition of 10% sarcosyl and 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. They were centrifuged at 245,000g for 45 min at 20 °C on 10% sucrose cushions. Pelleted material was resuspended in sample buffer, resolved by 16% Tris-tricine gels, electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies with epitope within PrP globular domain: 2D6 (human PrP epitope 140–160 (ref. 62), Sha31 (human PrP epitope 145–152 (ref. 63)). Immunoreactivity was visualized by chemiluminescence. Determination of PrPres glycoform ratios was performed with the GeneTools software after acquisition of the signals with a GeneGnome digital imager.

Histoblots

Brains were rapidly removed from euthanized mice and frozen on dry ice. Cryosections were cut at 8–10 μm, transferred onto Superfrost slides and kept at −20 °C until use. Histoblot analyses were performed as described30, using the 12F10 anti-PrP antibody64 (human PrP epitope 142–160). Analysis was performed with a digital camera (Coolsnap, Photometrics) mounted on a binocular glass (SZX12, Olympus). The sections presented are representative of the analysis of three brains samples. The protocol was similar to study PrPC distribution, except that the proteinase K treatment step was omitted65. The scale bar shown in Fig. 1 applies to all histoblots.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files, or available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Le Dur, A. et al. Divergent prion strain evolution driven by PrPC expression level in transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 8, 14170 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14170 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Collinge, J. Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 519–550 (2001).

Prusiner, S. B. Prions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13363–13383 (1998).

Bemporad, F. & Chiti, F. Protein misfolded oligomers: experimental approaches, mechanism of formation, and structure–toxicity relationships. Chem. Biol. 19, 315–327 (2012).

Diaz-Espinoza, R. & Soto, C. High-resolution structure of infectious prion protein: the final frontier. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 370–377 (2012).

Andreoletti, O. et al. Early accumulation of PrPSc in gut-associated lymphoid and nervous tissues of susceptible sheep from a Romanov flock with natural scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 3115–3126 (2000).

Andreoletti, O. et al. PrPSc accumulation in myocytes from sheep incubating natural scrapie. Nat. Med. 10, 591–593 (2004).

Mabbott, N. A. & MacPherson, G. G. Prions and their lethal journey to the brain. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 201–211 (2006).

Aguzzi, A., Nuvolone, M. & Zhu, C. The immunobiology of prion diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 888–902 (2013).

Beringue, V., Vilotte, J. L. & Laude, H. Prion agent diversity and species barrier. Vet. Res. 39, 47 (2008).

Bruce, M. E. TSE strain variation. Br. Med. Bull. 66, 99–108 (2003).

Collinge, J. & Clarke, A. R. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science 318, 930–936 (2007).

Weissmann, C., Li, J., Mahal, S. P. & Browning, S. Prions on the move. EMBO Rep. 12, 1109–1117 (2011).

Notari, S. et al. Effects of different experimental conditions on the PrPSc core generated by protease digestion: implications for strain typing and molecular classification of CJD. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16797–16804 (2004).

Tixador, P. et al. The physical relationship between infectivity and prion protein aggregates is strain-dependent. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000859 (2010).

Cronier, S. et al. Detection and characterization of proteinase K-sensitive disease-related prion protein with thermolysin. Biochem. J. 416, 297–305 (2008).

Silveira, J. R. et al. The most infectious prion protein particles. Nature 437, 257–261 (2005).

Kimberlin, R. H. & Walker, C. A. Evidence that the transmission of one source of scrapie agent to hamsters involves separation of agent strains from a mixture. J. Gen. Virol. 39, 487–496 (1978).

Haldiman, T. et al. Co-existence of distinct prion types enables conformational evolution of human PrPSc by competitive selection. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 29846–29861 (2013).

Bessen, R. A. & Marsh, R. F. Identification of two biologically distinct strains of transmissible mink encephalopathy in hamsters. J. Gen. Virol. 73, 329–334 (1992).

Thackray, A. M., Hopkins, L., Lockey, R., Spiropoulos, J. & Bujdoso, R. Emergence of multiple prion strains from single isolates of ovine scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 1482–1491 (2011).

Li, J., Browning, S., Mahal, S. P., Oelschlegel, A. M. & Weissmann, C. Darwinian evolution of prions in cell culture. Science 327, 869–872 (2010).

Telling, G. C. Transgenic mouse models of prion diseases. Methods Mol. Biol. 459, 249–263 (2008).

Tessier, P. M. & Lindquist, S. Prion recognition elements govern nucleation, strain specificity and species barriers. Nature 447, 556–561 (2007).

Asante, E. A. et al. BSE prions propagate as either variant CJD-like or sporadic CJD-like prion strains in transgenic mice expressing human prion protein. EMBO J. 21, 6358–6366 (2002).

Beringue, V. et al. A bovine prion acquires an epidemic bovine spongiform encephalopathy strain-like phenotype on interspecies transmission. J. Neurosci. 27, 6965–6971 (2007).

Scott, M. R. et al. Propagation of prion strains through specific conformers of the prion protein. J. Virol. 71, 9032–9044 (1997).

Beringue, V. et al. Facilitated cross-species transmission of prions in extraneural tissue. Science 335, 472–475 (2012).

Chapuis, J. et al. Emergence of two prion subtypes in ovine PrP transgenic mice infected with human MM2-cortical Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease prions. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 4, 10 (2016).

Collinge, J., Sidle, K. C., Meads, J., Ironside, J. & Hill, A. F. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature 383, 685–690 (1996).

Le Dur, A. et al. A newly identified type of scrapie agent can naturally infect sheep with resistant PrP genotypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16031–16036 (2005).

Beringue, V. et al. Prominent and persistent extraneural infection in human PrP transgenic mice infected with variant CJD. PLoS ONE 3, e1419 (2008).

Bruce, M. E. & Dickinson, A. G. Biological evidence that scrapie agent has an independent genome. J. Gen. Virol. 68, 79–89 (1987).

Torres, J. M. et al. Classical bovine spongiform encephalopathy by transmission of H-type prion in homologous prion protein context. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 1636–1644 (2011).

Masujin, K. et al. Emergence of a novel bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) prion from an atypical H-type BSE. Sci. Rep. 6, 22753 (2016).

Elsen, J. M. et al. Genetic susceptibility and transmission factors in scrapie: detailed analysis of an epidemic in a closed flock of Romanov. Arch. Virol. 144, 431–445 (1999).

Vilotte, J. L. et al. Markedly increased susceptibility to natural sheep scrapie of transgenic mice expressing ovine prp. J. Virol. 75, 5977–5984.

Heintz, N. BAC to the future: the use of bac transgenic mice for neuroscience research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 861–870 (2001).

Bartz, J. C., Bessen, R. A., McKenzie, D., Marsh, R. F. & Aiken, J. M. Adaptation and selection of prion protein strain conformations following interspecies transmission of transmissible mink encephalopathy. J. Virol. 74, 5542–5547 (2000).

Bessen, R. A. & Marsh, R. F. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J. Virol. 68, 7859–7868 (1994).

Deleault, N. R. et al. Cofactor molecules maintain infectious conformation and restrict strain properties in purified prions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1938–E1946 (2012).

Ma, J. The role of cofactors in prion propagation and infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002589 (2012).

Supattapone, S. Synthesis of high titer infectious prions with cofactor molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19850–19854 (2014).

Uptain, S. M., Sawicki, G. J., Caughey, B. & Lindquist, S. Strains of [PSI+] are distinguished by their efficiencies of prion-mediated conformational conversion. EMBO J. 20, 6236–6245 (2001).

Gonzalez, L. et al. Stability of murine scrapie strain 87 V after passage in sheep and comparison with the CH1641 ovine strain. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 3703–3714 (2015).

Cali, I. et al. Co-existence of scrapie prion protein types 1 and 2 in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: its effect on the phenotype and prion-type characteristics. Brain 132, 2643–2658 (2009).

Polymenidou, M. et al. Coexistence of multiple PrPSc types in individuals with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Lancet Neurol. 4, 805–814 (2005).

Mahal, S. P. et al. Prion strain discrimination in cell culture: the cell panel assay. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 20908–20913 (2007).

Beringue, V. et al. Regional heterogeneity of cellular prion protein isoforms in the mouse brain. Brain 126, 2065–2073 (2003).

DeArmond, S. J. et al. Selective neuronal targeting in prion disease. Neuron 19, 1337–1348 (1997).

Tuzi, N. L. et al. Host PrP glycosylation: a major factor determining the outcome of prion infection. PLoS Biol. 6, e100 (2008).

Saa, P. et al. Strain-specific role of RNAs in prion replication. J. Virol. 86, 10494–10504 (2012).

Jeffrey, M., Martin, S. & Gonzalez, L. Cell-associated variants of disease-specific prion protein immunolabelling are found in different sources of sheep transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 1033–1045 (2003).

Dron, M. et al. Endogenous proteolytic cleavage of disease-associated prion protein to produce C2 fragments is strongly cell- and tissue-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10252–10264 (2010).

Masel, J., Jansen, V. A. & Nowak, M. A. Quantifying the kinetic parameters of prion replication. Biophys. Chem. 77, 139–152 (1999).

Tanaka, M., Collins, S. R., Toyama, B. H. & Weissman, J. S. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature 442, 585–589 (2006).

Diaz-San Segundo, F. et al. Distribution of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) in brains of livestock and domesticated species. Acta Neuropathol. 112, 587–595 (2006).

Ford, M. J. et al. A marked disparity between the expression of prion protein and its message by neurons of the CNS. Neuroscience 111, 533–551 (2002).

Moya, K. L. et al. Immunolocalization of the cellular prion protein in normal brain. Microsc. Res. Tech. 50, 58–65 (2000).

Sales, N. et al. Cellular prion protein localization in rodent and primate brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10, 2464–2471 (1998).

Langevin, C., Andreoletti, O., Le Dur, A., Laude, H. & Beringue, V. Marked influence of the route of infection on prion strain apparent phenotype in a scrapie transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 41, 219–225 (2011).

Laude, H. et al. New in vivo and ex vivo models for the experimental study of sheep scrapie: development and perspectives. C. R. Biol. 325, 49–57 (2002).

Rezaei, H. et al. High yield purification and physico-chemical properties of full-length recombinant allelic variants of sheep prion protein linked to scrapie susceptibility. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 2833–2839 (2000).

Feraudet, C. et al. Screening of 145 anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies for their capacity to inhibit PrPSc replication in infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11247–11258 (2005).

Krasemann, S., Groschup, M. H., Harmeyer, S., Hunsmann, G. & Bodemer, W. Generation of monoclonal antibodies against human prion proteins in PrP0/0 mice. Mol. Med. 2, 725–734 (1996).

Taraboulos, A. et al. Regional mapping of prion proteins in brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 7620–7624 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Animalerie Rongeurs (INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France) for animal care, J.M. Elsen (INRA, Toulouse, France) for providing scrapie-infected sheep material, Eric Ross (Colorado State University) and Ilia Baskakov (University of Maryland School of Medicine) for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the European Network of Excellence NeuroPrion, from the GIS Prions (Groupement d’intérêt scientifique Prions), and from INRA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.B., J-L.V. and H.L. conceived and designed the experiments. A.L.D., T.L.L., M.-G.S., A.L., N.C., S.R., B.P., F.R., L.H., H.R., V.B., J.-L.V. and H.L. performed the experiments. A.L.D., T.L.L., N.C., B.P., H.R., V.B., J.-L.V. and H.L. analysed the data. V.B., J.-L.V. and H.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References (PDF 4638 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Le Dur, A., Laï, T., Stinnakre, MG. et al. Divergent prion strain evolution driven by PrPC expression level in transgenic mice. Nat Commun 8, 14170 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14170

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14170

This article is cited by

-

Prion assemblies: structural heterogeneity, mechanisms of formation, and role in species barrier

Cell and Tissue Research (2023)

-

New developments in prion disease research using genetically modified mouse models

Cell and Tissue Research (2023)

-

Classical scrapie in small ruminants is caused by at least four different prion strains

Veterinary Research (2021)

-

Review on PRNP genetics and susceptibility to chronic wasting disease of Cervidae

Veterinary Research (2021)

-

Therapeutic Assay with the Non-toxic C-Terminal Fragment of Tetanus Toxin (TTC) in Transgenic Murine Models of Prion Disease

Molecular Neurobiology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.