Abstract

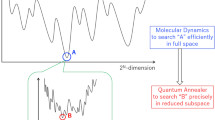

Exploiting quantum properties to outperform classical ways of information processing is an outstanding goal of modern physics. A promising route is quantum simulation, which aims at implementing relevant and computationally hard problems in controllable quantum systems. Here we demonstrate that in a trapped ion setup, with present day technology, it is possible to realize a spin model of the Mattis-type that exhibits spin glass phases. Our method produces the glassy behaviour without the need for any disorder potential, just by controlling the detuning of the spin-phonon coupling. Applying a transverse field, the system can be used to benchmark quantum annealing strategies which aim at reaching the ground state of the spin glass starting from the paramagnetic phase. In the vicinity of a phonon resonance, the problem maps onto number partitioning, and instances which are difficult to address classically can be implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin models are paradigms of multidisciplinary science: They find several applications in various fields of physics, from condensed matter to high-energy physics, but also beyond the physical sciences. In neuroscience, the famous Hopfield model describes brain functions such as associative memory by an interacting spin system1. This directly relates to computer and information sciences, where pattern recognition or error-free coding can be achieved using spin models2. Importantly, many optimization problems, like number partitioning or the travelling salesman problem, belonging to the class of NP-hard problems, can be mapped onto the problem of finding the ground state of a specific spin model3,4. This implies that solving spin models is a task for which no general efficient classical algorithm is known to exist. In physics, analytic replica methods have been developed in the context of spin glasses5,6. A controversial development, supposed to provide also an exact numerical understanding of spin glasses, regards the D-Wave machine. Recently introduced in the market, this device solves classical spin glass models, but the underlying mechanisms are not clear, and it remains an open question whether it provides a speed-up over the best classical algorithms7,8,9.

This triggers interest in alternative quantum systems designed to solve the general spin models via quantum simulation. A noteworthy physical system for this goal are trapped ions: Nowadays, spin systems of trapped ions are available in many laboratories10,11,12,13,14,15, and adiabatic state preparation, similar to quantum annealing, is experimental state-of-art. Moreover, such system can exhibit long-range spin–spin interactions16 mediated by phonon modes, leading to a highly connected spin model. Here we demonstrate how to profit from these properties, using trapped ions as a quantum annealer of a classical spin glass model.

We consider a setup described by a time-dependent Dicke-like model:

with am annihilating a phonon in mode m with frequency ωm and characterized by the normalized collective coordinates ξim. The second term in H0 couples the motion of the ions to an internal degree of freedom (spin) through a Raman beam which induces a spin flip on site i, described by  , and (de)excites a phonon in mode m. Here, Ωi is the Rabi frequency, ħωrecoil the recoil energy, and ωL the beatnote frequency of the Raman lasers. Before also studying the full model, we consider a much simpler effective Hamiltonian, derived from equation (1) by integrating out the phonons16,17,18,19. The model then reduces to a time-independent Ising-type spin Hamiltonian

, and (de)excites a phonon in mode m. Here, Ωi is the Rabi frequency, ħωrecoil the recoil energy, and ωL the beatnote frequency of the Raman lasers. Before also studying the full model, we consider a much simpler effective Hamiltonian, derived from equation (1) by integrating out the phonons16,17,18,19. The model then reduces to a time-independent Ising-type spin Hamiltonian

Each phonon mode contributes to the effective coupling Jij in a factorizable way, proportional to ξimξjm, and weighted by the inverse of the detuning from the mode Δm=ωm−ωL:

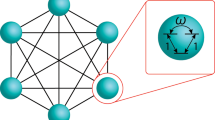

The ξim imprint a pattern to the spin configuration, similar to the associative memory in a neural network1,20. The connection between multi-mode Dicke models with random couplings, the Hopfield model, and spin glass physics has been the subject of recent research21,22,23, and the possibility of addressing number partitioning was mentioned in this context23.

Before proceeding, we remind the reader that the concept of a spin glass used in the literature may have different and controversial meanings (cf., refs 24, 25, 26, 27): (i) long-range spin glass models5 and neural networks28,29, believed to be captured by the Parisi picture30,31 and replica symmetry breaking. These lead to hierarchical organization of the exponentially degenerated free-energy landscape, breakdown of ergodicity and aging, slow dynamics due to a continuous splitting of the metastable states with decreasing temperatures (cf., ref. 32). (ii) Short-range spin glass models believed to be captured by the Fisher–Huse33,34 droplet/scaling model with a single ground state (up to a total spin flip), but a complex structure of the domain walls. For these models, aging, rejuvenation and memory, if any, have different nature and occurrence32,35; (iii) Mattis glasses36, where the huge ground-state degeneracy becomes an exponential quasi-degeneracy, for which finding the ground state becomes computationally hard37 (see the subsection ‘Increasing complexity’ in the ‘Results’ section). Note that exponential (quasi)degeneracy of the ground states (or the free-energy minima) characterizes also other interesting states: certain kinds of spin liquids or spin ice, and so on.

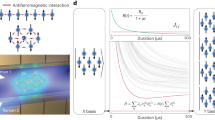

Here we analyse the trapped ion setup. Even without explicit randomness (Ωi=Ω=const.), the coupling to a large number of phonon modes suggests the presence of glassy behaviour. This intuition comes from the fact that the associative memory of the related Hopfield model works correctly if the number of patterns is at most 0.138N, where N is the number of spins28. For a larger number of patterns, the Hopfield model exhibits glassy behaviour since many patterns have similar energy and the dynamics gets stuck in local minima. However, it is not clear a priori how the weighting of each pattern, present in equation (3), modifies the behaviour of the spin model. In certain regimes the detuning suggests to neglect the contributions from all but one mode, leading to a Mattis-type model with factorizable couplings36, Jij∝ξimξjm. The possibility of negative detuning, that is, antiferromagnetic coupling to a pattern, drives such system into a glassy phase, characterized by a huge low-energy Hilbert space. The antiferromagnetic Mattis model is directly connected to the potentially NP-hard task of number partitioning37,38. Its solution can then be found via quantum annealing, that is, via adiabatic ramping down of a transverse magnetic field, see also the proposal of ref. 39 for a frustrated ion chain.

We start by giving analytical arguments to demonstrate the glassy behaviour in the classical spin chains. Using exact numerics, we then focus on the quantum Mattis model. By calculating the magnetic susceptibility, and an Edward–Anderson-like order parameter, we distinguish between glassy, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic regimes. The annealing dynamics is investigated using exact numerics and a semi-classical approximation. We demonstrate the feasibility of annealing for glassy instances. Finally, we show that the memory in the quantum Hopfield model is real-valued rather than binary. This property might be useful for various applications of quantum neural networks such as pattern-recognition schemes.

Results

Tunable spin–spin interactions

We start our analysis by inspecting the phonon modes. For a sufficiently anisotropic trapping potential, the ions self-arrange in a line along the z-axis40,41. The phonon Hamiltonian Hph is obtained by a second-order expansion of Coulomb and trap potentials around these equilibrium positions zi:  , with qi the displacement of the ith ion from equilibrium. For the transverse phonon branch, Vij is given by16

, with qi the displacement of the ith ion from equilibrium. For the transverse phonon branch, Vij is given by16

Our exact numerical simulations have been performed for six 40Ca+ ions in a trap of frequency ω⊥=2π × 2.655 MHz, as used in a recent experiment14. To maximize the bandwidth of the phonon spectrum and thereby facilitate the annealing process, we choose the radial trap frequency ωz as large as allowed to avoid zig-zag transitions, ωz≲1.37ω⊥·N−0.86. Diagonalizing the matrix Vij leads to the previously introduced mode vectors ξm=(ξ1m, …, ξNm), which are normalized to one, and ordered according to their frequency ωm:

The mode ξN with largest frequency, ωN=ω⊥, is the centre-of-mass mode, ξiN=N−1/2. Parity symmetry of Vij is reflected by the modes, ξim=±ξ(N+1−i)m, and even (+) and odd (−) modes alternate in the phonon spectrum. We focus on even N, for which all components ξim are non-zero. Except for the centre-of-mass mode, all modes fulfil ∑i ξim=0.

Previous experiments10,11,12,13,14 have mostly been performed with a beatnote frequency ωL several kHz above ωN, leading to an antiferromagnetic coupling Jij<0 with power-law decay, see Fig. 1a. Despite the presence of many modes, the couplings Jij then take an ordered structure. This work, in contrast, focuses on the regime ωL<ωN, where modes with both positive and negative ξim contribute, and ferro and antiferromagnetic couplings coexist, see Fig. 1b. This reminds of the disordered scenario of common spin glass models like the Sherrington–Kirkpatrick model5. In the following we study the properties of the time-independent effective spin model, before considering the full time-depedent problem involving spin-phonon coupling.

We plot the coupling constants Jij (in units of  ), for a system of six ions at different detunings δ=ωN−ωL. Rabi frequencies are taken as constants Ωi=const. (a) For negative detuning, δ=−2π × 159 kHz, interactions have a power-law decay. (b) For positive detuning, δ=2π × 796 kHz, the coupling constants resemble a spin glass.

), for a system of six ions at different detunings δ=ωN−ωL. Rabi frequencies are taken as constants Ωi=const. (a) For negative detuning, δ=−2π × 159 kHz, interactions have a power-law decay. (b) For positive detuning, δ=2π × 796 kHz, the coupling constants resemble a spin glass.

Classical Mattis model

Close to a resonance with one phonon mode, simple arguments allow for deducing the spin configurations of the ground states. In this limit, we can neglect the other modes, leading to a Mattis model. A single pattern ξm then determines the coupling, Jij∝ξimξjm. The sign of Jij depends on the sign of the detuning: Below the resonance, we have sign(Jij)=sign(ξimξjm), and accordingly the energy  is minimized if

is minimized if  and

and  are either both aligned or both anti-aligned with ξim and ξjm. Thus, we have a twofold degenerate ground state given by the patterns ±[sign(ξ1m), …, sign(ξNm)]. We refer to this scenario as the ferromagnetic side of a resonance.

are either both aligned or both anti-aligned with ξim and ξjm. Thus, we have a twofold degenerate ground state given by the patterns ±[sign(ξ1m), …, sign(ξNm)]. We refer to this scenario as the ferromagnetic side of a resonance.

Crossing the resonance, the overall sign of the Hamiltonian changes. Naively, one might assume that this should not qualitatively affect the physics, since we have  , that is, there is an equal balance between positive and negative Jij. This expectation, however, turns out to be false. Recalling the relation between the Mattis model and number partitioning4,37,38, the antiferromagnetic model maps onto an optimization problem in which the task is to find the optimal bi-partition of a given sequence of numbers (ξi)i, such that the cost function

, that is, there is an equal balance between positive and negative Jij. This expectation, however, turns out to be false. Recalling the relation between the Mattis model and number partitioning4,37,38, the antiferromagnetic model maps onto an optimization problem in which the task is to find the optimal bi-partition of a given sequence of numbers (ξi)i, such that the cost function  is minimized. Here, the two partitions are denoted by ↑ and ↓. For a Hamiltonian of the form

is minimized. Here, the two partitions are denoted by ↑ and ↓. For a Hamiltonian of the form  , eigenvectors of

, eigenvectors of  are Hamiltonian eigenstates with an energy precisely given by the cost function E. Thus, in the limit of just one antiferromagnetic resonance, the ground state of H is exactly the configuration that minimizes the cost function.

are Hamiltonian eigenstates with an energy precisely given by the cost function E. Thus, in the limit of just one antiferromagnetic resonance, the ground state of H is exactly the configuration that minimizes the cost function.

With this insight, the ground states of the spin model are easily found exploiting the system’s parity symmetry: For even modes, ξim=ξ(N+1−i)m, and we simply have to choose  to minimize the cost function. For odd modes, ξim=−ξ(N+1−i)m, and we must choose

to minimize the cost function. For odd modes, ξim=−ξ(N+1−i)m, and we must choose  . In both cases, this implies that we can choose half of the spins arbitrarily, leading to at least 2N/2 ground states.

. In both cases, this implies that we can choose half of the spins arbitrarily, leading to at least 2N/2 ground states.

The important observation is that an exponentially large number of ground states exists in the limit of being arbitrarily close above a resonance. This is a characteristic feature of spin glasses, yet it does not lead to computational hardness. In fact, as pointed out in ref. 38, the number-partitioning problem with exponentially many perfect partitions belongs to the ‘easy phase’. How to reach hard instances will be explained in the section below.

Pushing our arguments further we consider the influence of a second resonance: In between two resonances, the exponential degeneracy of the antiferromagnetic coupling on one side is lifted by the influence of the ferromagnetically coupled mode on the other side. Interestingly, this does not lead to frustration, since even- and odd-parity modes alternate in the phonon spectrum, and the pattern favoured by the ferromagnetic coupling is always contained in the ground state manifold of the antiferromagnetic coupling. Accordingly, between two modes the ground-state pattern is uniquely defined by the upper mode.

Beyond this two-mode approximation, we rely on numerical results. Taking into account all modes, exact diagonalization of a small system (N≤10) shows that the two-mode model captures the behaviour correctly: At any detuning, the degeneracy due to the nearest antiferromagnetic coupling is lifted in favour of the pattern of the next ferromagnetic coupling. In Fig. 2a, we plot the cumulative density of states ρcum(E), that is, the number of states with an energy below E. The corresponding phonon resonances ωm are marked in Fig. 2b. The curves clearly reflect the very different behaviour in the red- and blue-detuned regimes: Fig. 2 illustrates the quick increase of ρcum(E) at low energies, when the laser detuning is chosen on the antiferromagnetic side of a phonon resonance. In contrast, a low density of states characterizes the system on the ferromagnetic side of a resonance. In intermediate regimes, as shown for δ=2π × 199 kHz, the spectrum is symmetric.

(a) For six ions and at trap frequency ωz=2π × 770 kHz, we plot the number of states (divided by the total Hilbert space dimension) below the normalized energy treshold (0: ground state energy, 1: energy of highest state), for different detunings from the centre-of-mass mode, δ=ωN−ωL. The density of states at low energies is seen to strongly increase when the detuning is slightly above a phonon resonance. In b the position of the resonances (measured from the centre-of-mass mode at δN=0) are shown.

A breakdown of the two-mode approximation is expected for large numbers of spins: Since the distance between neighbouring resonances approximately scales with 1/N (at fixed trap frequencies), the influence of additional modes grows with the system size. The combined contribution of all antiferromagnetically coupled modes tries to select the fully polarized configurations as the true ground state, while all ferromagnetically coupled modes, except for the centre-of-mass mode, favour fully unpolarized configurations. As a consequence, it is a priori unclear which pattern will be selected in the presence of many modes.

This observation is crucial from the point of view of a complexity theory. In the presence of parity symmetry neither the one-mode problem (that is, the number-partitioning problem), nor the two-mode approximation are hard problems, as they can be solved by simple analytic arguments. However, when many modes lift the degeneracy of the exponentially large low-energy manifold in an a priori unknown way, one faces the situation where a true but unknown ground state is separated only by a very small gap. Identifying this state then usually requires scanning an exponentially large number of low-energy states, and classical annealing algorithms can easily get stuck in a wrong minimum. Below, we discuss how a transverse magnetic field opens up a way of finding the ground state via quantum annealing. Moreover, we will discuss strategies to make also the one-mode model, that is, the number-partitioning problem, computationally complex.

Increasing complexity

As discussed above, the instances of the number-partitioning problem realized in the ion chain are simple to solve due to parity symmetry. This is a convenient feature when testing the correct functioning of the quantum simulation, but our goal is the implementation of computationally complex and selectable instances of the problem in the device. One strategy is the use of microtraps to hold the ions42. The equilibrium positions of the ions can then be chosen at will, opening up the possibility to control the values of the ξim. The computational complexity of the number-partitioning problem then depends on the precision with which the ξim can be tuned. If the number of digits can be scaled with the number of spins, one enters the regime where number partitioning is proven to be NP-hard38. Thus, the number of digits must at least be of order log10 N, which poses no problem for realistic systems involving tens of ions.

Another way of enhancing complexity even within a parity-symmetric trap would be to ‘deactivate’ some spins by a fast pump laser. For example, if all spins on the left half of the chain are forced to oscillate,  , the part of the Hamiltonian which remains time-independent poses a number-partitioning problem of N/2 different numbers.

, the part of the Hamiltonian which remains time-independent poses a number-partitioning problem of N/2 different numbers.

Another promising approach was recently suggested in ref. 43: operating on the antiferromagnetic side of the centre-of-mass resonance, single-site addressing allows one to use the Rabi frequency for defining the instance of the number-partitioning problem. This could indeed be the step to turn the trapped ions setup into a universal number-partitioning solver, where arbitrary user-defined instances can be implemented.

If one is not interested in the number-partitioning problem itself, one might also increase the system’s complexity via resonant coupling to more than one mode. Equipping the Raman laser with several beatnote frequencies  and Rabi frequencies

and Rabi frequencies  , it is possible to engineer couplings of the form44:

, it is possible to engineer couplings of the form44:

With an appropriate choice of Rabi frequencies and detunings, this allows for realizing the Hopfield model,  , where each coupling μ is assumed to be in resonance with one mode mμ. For ferromagnetic couplings, the low-energy states again are determined by the signs of the

, where each coupling μ is assumed to be in resonance with one mode mμ. For ferromagnetic couplings, the low-energy states again are determined by the signs of the  , but in general the different low-energy patterns are not degenerate, and a glassy regime is expected for large μmax (ref. 28).

, but in general the different low-energy patterns are not degenerate, and a glassy regime is expected for large μmax (ref. 28).

Quantum phases

So far, we have considered classical spin chains lacking any non-commuting terms in the Hamiltonian. Quantum properties come into play if we either add an additional coupling  , or a transverse magnetic field:

, or a transverse magnetic field:

The latter has been realized in several experiments10,12,14, and is convenient for our purposes, as the field strength B, if decaying with time, provides an annealing parameter: For large B, all spins are polarized along the z-direction, whereas for vanishing B one obtains the ground state of the classical Ising chain. As argued above, the latter exhibits spin glass phases with an exponentially large low-energy subspace. Even in those cases where the true ground state is known theoretically, finding it experimentally remains a difficult task. Our system hence provides an ideal test ground for experimenting with different annealing strategies.

Before presenting results for the simulated quantum annealing, let us first discuss the different phases expected for the effective Hamiltonian  . The last term is a bias introduced to break the Z2 symmetry. Our distinction between phases is based on certain quantities which combine thermal and quantum averages

. The last term is a bias introduced to break the Z2 symmetry. Our distinction between phases is based on certain quantities which combine thermal and quantum averages

with  denoting the Hamiltonian eigenstates at energy Eλ. For α=1,

denoting the Hamiltonian eigenstates at energy Eλ. For α=1,  reduces to the normal thermal average. We will use low, but non-zero temperatures T of the order of the coupling constant, accounting in this way for the huge quasi-degeneracy in the glassy regime. The thermal average

reduces to the normal thermal average. We will use low, but non-zero temperatures T of the order of the coupling constant, accounting in this way for the huge quasi-degeneracy in the glassy regime. The thermal average  plays a role somewhat similar to the disorder average, as it averages over various quasi-ground states (pure thermodynamic phases). We therefore expect

plays a role somewhat similar to the disorder average, as it averages over various quasi-ground states (pure thermodynamic phases). We therefore expect  to go to zero in the glassy phase. In contrast, a non-zero average

to go to zero in the glassy phase. In contrast, a non-zero average  detects the ferromagnetic phase of the Mattis model, while it vanishes in the paramagnetic state. Taking its square to get rid of the sign, we obtain a global ferromagnetic order parameter by summing over all spins:

detects the ferromagnetic phase of the Mattis model, while it vanishes in the paramagnetic state. Taking its square to get rid of the sign, we obtain a global ferromagnetic order parameter by summing over all spins:

On the other hand, in the spirit of an Edwards–Anderson-like parameter, we consider thermal averages of squared quantum averages, that is,

At a sufficiently low temperature this average would still be zero for a paramagnetic system, but now it remains non-zero for both ferromagnetic and glassy systems. Accordingly, a parameter which is ‘large’ only for glassy systems is given by the ratio  , used in Fig. 3 to detect the glassy regions.

, used in Fig. 3 to detect the glassy regions.

On varying the laser detuning δ and the transverse magnetic field B, we mark, for N=6 ions and ωz=2π × 770 kHz, those regions in configuration space where the ferromagnetic order parameter νFM, the spin glass order parameter νSG, or the longitudinal magnetic susceptibility χ take larger than average values ( =0.13,

=0.13,  =5,

=5,  =1.6). Below each phonon resonance (marked by the dashed horizontal lines), there is a regime where large values of νSG and χ indicate spin glass behaviour for sufficiently weak transverse field B. To break the Z2 symmetry of the Hamiltonian, all quantities were calculated in the presence of a biasing field

=1.6). Below each phonon resonance (marked by the dashed horizontal lines), there is a regime where large values of νSG and χ indicate spin glass behaviour for sufficiently weak transverse field B. To break the Z2 symmetry of the Hamiltonian, all quantities were calculated in the presence of a biasing field  (with

(with  ).

).

Thermal averages are difficult to measure, but the contained information is also present in linear response functions at zero temperature. Therefore, we have calculated the longitudinal magnetic susceptibility χ, that is, the response of the system to a small local magnetic field  along the σx direction (in units Jrms−2):

along the σx direction (in units Jrms−2):

Due to the (quasi)degeneracy in the glass, one expects a huge response even from a weak field, and thus a divergent susceptibility.

We have calculated νFM, νSG and χ, for N=6 between 0≤2π × δ≤8 MHz, and 0≤B≤4Jrms. For the thermal averaging, we have chosen a temperature kBT=Jrms. The results are summarized in Fig. 3, indicating the regions where these quantities take larger values than their configurational averages  ,

,  and

and  , defined as

, defined as  . In this way, we identify and distinguish ferromagnetic behaviour below, and glassy behaviour above each resonance. Regions of large susceptibility χ overlap with regions of large νSG, attaining numerical values which are three orders of magnitude larger than the corresponding averages. For sufficiently strong field B, in contrast, none of these parameters is large, indicating paramagnetic behaviour.

. In this way, we identify and distinguish ferromagnetic behaviour below, and glassy behaviour above each resonance. Regions of large susceptibility χ overlap with regions of large νSG, attaining numerical values which are three orders of magnitude larger than the corresponding averages. For sufficiently strong field B, in contrast, none of these parameters is large, indicating paramagnetic behaviour.

Note that the existence of the purported glassy phase in the quantum case is an open problem. We provide here the evidence only for small systems, since it is numerically feasible and corresponds directly to current or near-future experiments. If we increase the complexity of our system by resonant coupling to many phonon modes, as discussed in the last paragraph of the previous subsection, the glassy behaviour will result from the interplay of contributions of many modes similarly as in the Hopfield model with Hebbian rule and random memory patterns. Here the beautiful results by Strack and Sachdev21—the quantum analogue of the Amit et al.29 machinery—can be applied directly to obtain the phase diagram for large N. If, however, we increase the complexity by random positioning of the ion traps, then the resonance condition will pick up the contribution from one dominant (random) mode, and the Hebbian picture will apply.

Simulated quantum annealing

We will now turn to the more realistic description of the system in terms of a time-dependent Dicke model, described by the Hamiltonian H0(t) in equation (1) with an additional transverse field HB(t) from equation (7). We assume an exponential annealing protocol  . Again we apply a bias field

. Again we apply a bias field  , lifting the Z2 degeneracy of the classical ground state. We study the exact time evolution under the Hamiltonian H(t)=H0(t)+HB(t)+hbias, using a Krylov subspace method45, and truncating the phonon number to a maximum of two phonons per mode.

, lifting the Z2 degeneracy of the classical ground state. We study the exact time evolution under the Hamiltonian H(t)=H0(t)+HB(t)+hbias, using a Krylov subspace method45, and truncating the phonon number to a maximum of two phonons per mode.

Initially, the system is cooled to the motional ground state, and spins are polarized along σz. Choosing  , this configuration is close to the ground state of the effective model HJ+HB+hbias at t=0. If the decay of B(t) is slow enough, and if the entanglement between spins and phonons remains sufficiently low, the system stays close to the ground state for all times, and finally reaches the ground state of HJ.

, this configuration is close to the ground state of the effective model HJ+HB+hbias at t=0. If the decay of B(t) is slow enough, and if the entanglement between spins and phonons remains sufficiently low, the system stays close to the ground state for all times, and finally reaches the ground state of HJ.

We have simulated this process for N=6 ions, as shown in Fig. 4. As a result of the annealing, we are not interested in the final quantum state, but only in the signs of  , which fully determine the system in the classical configuration. This provides some robustness. We find that for a successful annealing procedure, yielding the correct sign for all i, the number of phonons produced during the evolution should not be larger than 1. At fixed detuning, we can reduce the number of phonons by decreasing the Rabi frequency, at the expense of increasing time scales. As a realistic choice14,15, we demand that annealing is achieved within tens of miliseconds.

, which fully determine the system in the classical configuration. This provides some robustness. We find that for a successful annealing procedure, yielding the correct sign for all i, the number of phonons produced during the evolution should not be larger than 1. At fixed detuning, we can reduce the number of phonons by decreasing the Rabi frequency, at the expense of increasing time scales. As a realistic choice14,15, we demand that annealing is achieved within tens of miliseconds.

Unitary time evolution of the full system (N=6) for different laser detunings δ between the fourth and fifth resonance. Thick lines show the result of the exact evolution, while the thin lines have been obtained from the semi-classical approximation. In all cases, the desired pattern (+++−−−) can be read out after sufficiently long annealing times. While in a,b we operate at the onset of glassiness, δ=2π × 239 kHz, c considers a ferromagnetic instance, δ=2π × 143 kHz. The annealing protocol in a is defined by Bmax=50Jrms and  ms. In b the same instance is solved with higher fidelity by choosing Bmax=80 Jrms and

ms. In b the same instance is solved with higher fidelity by choosing Bmax=80 Jrms and  ms. Fast annealing, with Bmax=50 Jrms and

ms. Fast annealing, with Bmax=50 Jrms and  ms, is possible in the ferromagnetic instance in (c). In all simulations, we have chosen Ω=2π × 50 kHz, ωrecoil=2π × 15 kHz, and

ms, is possible in the ferromagnetic instance in (c). In all simulations, we have chosen Ω=2π × 50 kHz, ωrecoil=2π × 15 kHz, and  kHz.

kHz.

Figure 4a shows that one can operate at a detuning δ=2π × 239 kHz, that is, at the onset of a glassy phase according to Fig. 3. The mode vector which selects the ground state is ξ5=(0.61, 0.34, 0.11, −0.11, −0.34, −0.61), and the corresponding pattern can be read out after an annealing time t≥15 ms. On the other hand, even for long times,  saturates only at −0.15, which is far from the classical value −1. As shown in Fig. 4b, a slower annealing protocol leads to more robust results

saturates only at −0.15, which is far from the classical value −1. As shown in Fig. 4b, a slower annealing protocol leads to more robust results  . In Fig. 4c, a much simpler instance in the ferromagnetic regime is considered. Good results

. In Fig. 4c, a much simpler instance in the ferromagnetic regime is considered. Good results  can then be obtained within only a few ms.

can then be obtained within only a few ms.

In addition, dephasing due to instabilities of applied fields and spontaneous emission processes disturb the dynamics of the spins. In ref. 43 a master equation was derived that takes into account such noisy environment. To study the evolution of the system in this open scenario we have applied the Monte Carlo wave-function method46. As quantum jump operators are hermitean,  for dephasing and

for dephasing and  for spontaneous emission, the evolution remains unitary, but is randomly interrupted by quantum jumps. Each jump has equal probability Γ, and the average number of jumps within the annealing time T is given by

for spontaneous emission, the evolution remains unitary, but is randomly interrupted by quantum jumps. Each jump has equal probability Γ, and the average number of jumps within the annealing time T is given by  , which we chose close to 1.

, which we chose close to 1.

Since a faithful description requires statistics over many runs, we restrict ourselves to a small system, N=4, with short annealing times. In a sample of 100 runs, we noted 94 jumps (42 σx and 52 σz jumps). In 39 runs, no jump occured. Among the 61 runs in which at least one jump occured, 26 runs still produced the correct sign for all spin averages  . The full time evolution, averaged over all runs, is shown in Fig. 5. On average, the final result is (0.65, 0.50, −0.41, −0.68), that is, our annealing with noise still produces the correct answer, but with lower fidelity.

. The full time evolution, averaged over all runs, is shown in Fig. 5. On average, the final result is (0.65, 0.50, −0.41, −0.68), that is, our annealing with noise still produces the correct answer, but with lower fidelity.

Using a Monte Carlo wave-function description averaged over 100 runs, we simulate the annealing process with N=4 ions in the presence of dephasing and spontaneous emission. With a noise rate Γ=0.03 Jrms ≈120 Hz and a total annealing time T=1 ms, we have on average one jump per run,  . We plot expectation values of the spins and total number of phonons, produced by the coupling, as a function of time. Here, we have operated in the ferromagnetic regime between the second and third phonon resonance, δ=2π × 159 kHz. Choosing Ω=2π × 50 kHz, ωrecoil=2π × 15 kHz, ωz=2π × 876 kHz, Bmax=50 Jrms≈200 kHz, and

. We plot expectation values of the spins and total number of phonons, produced by the coupling, as a function of time. Here, we have operated in the ferromagnetic regime between the second and third phonon resonance, δ=2π × 159 kHz. Choosing Ω=2π × 50 kHz, ωrecoil=2π × 15 kHz, ωz=2π × 876 kHz, Bmax=50 Jrms≈200 kHz, and  kHz, we are able to perform very fast annealing,

kHz, we are able to perform very fast annealing,  ms, with high fidelity. After a time T=1 ms, the time evolution without noise has converged to

ms, with high fidelity. After a time T=1 ms, the time evolution without noise has converged to  =(0.97, 0.70, −0.65, −0.85), correctly reproducing the classical pattern (++−−).

=(0.97, 0.70, −0.65, −0.85), correctly reproducing the classical pattern (++−−).

Whether an individual jump harms the evolution crucially depends on the time at which it occurs: While a spin flip (σz noise) is harmless in the beginning of the annealing, a dephasing event (σx noise) at an early stage of the evolution leads to wrong results. Oppositely, at the end of the annealing procedure, dephasing becomes harmless while spontaneous emission falsifies the result. An optimal annealing protocol has to balance the effect of different noise sources against non-adiabatic effects in the unitary evolution.

Scalability

Above we have demonstrated the feasibility of the proposed quantum annealing scheme in small systems. The usefulness of the approach, however, depends crucially on its behaviour on increasing the system size. While the exact treatment of the dynamics becomes intractable for longer chains, an efficient description can be derived from the Heisenberg equations:

with H=H0(t)+HB(t)+hbias. To solve this set of 5N first-order differential equations, we make a semi-classical approximation  , and then proceed numerically using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta algorithm. The semi-classical approximation is justified as long as the system remains close to the phonon vacuum. A direct comparison with exact results for six ions (see Fig. 4) shows that the semi-classical approach, while slightly overestimating fidelities, accurately reproduces all relevant time scales.

, and then proceed numerically using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta algorithm. The semi-classical approximation is justified as long as the system remains close to the phonon vacuum. A direct comparison with exact results for six ions (see Fig. 4) shows that the semi-classical approach, while slightly overestimating fidelities, accurately reproduces all relevant time scales.

This approach allows us to extend our simulations up to N=22 ions, at trap frequency ωz=2π × 270 kHz. We operate between the first and second resonance where the level spacing is largest, at a beatnote frequency ωL=ω1+0.2(ω2−ω1), that is with a fixed relative detuning between the two modes. This choice corresponds to δ=2π × 1.2 MHz in Fig. 3, characterized as a glassy instance of the system.

Our aim is to find the relation of annealing time, measured by the decay parameter  , and system size while the fidelity F is kept constant. For a practical definition we demand that F is zero when the annealing fails, that is when the sign of the spin averages

, and system size while the fidelity F is kept constant. For a practical definition we demand that F is zero when the annealing fails, that is when the sign of the spin averages  does not agree with the classical target state for all i. If the annealing finds the correct signs, the robustness still depends on the absolute values of the spin averages. The fidelity is then defined as the smallest absolute value,

does not agree with the classical target state for all i. If the annealing finds the correct signs, the robustness still depends on the absolute values of the spin averages. The fidelity is then defined as the smallest absolute value,  . Our results are summarized in Fig. 6: First, this figure shows that for all sizes N≤20 large fidelities F≥0.5 can be produced within experimentally feasible time scales,

. Our results are summarized in Fig. 6: First, this figure shows that for all sizes N≤20 large fidelities F≥0.5 can be produced within experimentally feasible time scales,  ms. Second, the time scale

ms. Second, the time scale  needed for a fidelity F=0.5 fits well to a fourth-order polynomial in N (with subleading terms of the order exp(1/N)):

needed for a fidelity F=0.5 fits well to a fourth-order polynomial in N (with subleading terms of the order exp(1/N)):

We solve the equations of motion, equation (12), for a glassy instance at different system sizes N, and plot the fidelity of the outcome as a function of the annealing time  . In the inset, we investigate the scaling behaviour by plotting (in double-logarithmic scale) the value of

. In the inset, we investigate the scaling behaviour by plotting (in double-logarithmic scale) the value of  which is needed for a fidelity F=0.5 as a function of N. A fourth-order polynomial fit agrees very well with the data (black dashed line). The fit parameters, as defined by equation (13), are

which is needed for a fidelity F=0.5 as a function of N. A fourth-order polynomial fit agrees very well with the data (black dashed line). The fit parameters, as defined by equation (13), are  ms and γ=12.0±1.2. For all calculations, we have chosen a beatnote frequency between the two lowest resonances, ωL=0.8ω1+0.2ω2, a trap frequency ωz=2π × 270 kHz, and a bias potential

ms and γ=12.0±1.2. For all calculations, we have chosen a beatnote frequency between the two lowest resonances, ωL=0.8ω1+0.2ω2, a trap frequency ωz=2π × 270 kHz, and a bias potential  kHz. The initial value of the transverse field was Bmax=10 kHz.

kHz. The initial value of the transverse field was Bmax=10 kHz.

with  and γ being free fit parameters. Although the sample of 22 ions is too small to draw strong conclusions, it is noteworthy that the polynomial fit is more accurate than an exponential one. This suggests that the proposed quantum simulation is indeed an efficient way of solving a complex computational problem. One should also keep in mind that our estimates, based on a semi-classical approximation, neglect certain quantum fluctuations which could further speed-up the annealing process.

and γ being free fit parameters. Although the sample of 22 ions is too small to draw strong conclusions, it is noteworthy that the polynomial fit is more accurate than an exponential one. This suggests that the proposed quantum simulation is indeed an efficient way of solving a complex computational problem. One should also keep in mind that our estimates, based on a semi-classical approximation, neglect certain quantum fluctuations which could further speed-up the annealing process.

To study the scaling of dissipative effects, we have extendend the Monte Carlo wave-function approach to larger systems, which is feasible if the phonon dynamics is neglected. The unitary part of the evolution is then described by the effective Ising Hamiltonian Heff=HJ+HB(t)+hbias. The dissipative part consists of random quantum jumps described by  and

and  . The results for a glassy instance (δ=2π × 198 kHz at ωz=2π × 700 kHz) are summarized in Table 1 for N=4, 6, 8. The noise rate is chosen such that on average one quantum jump occurs in the system with four ions, while accordingly the system with eight ions suffers on average from two such events. In all cases, the annealing produces the correct pattern, F>0. As expected, F decreases for larger systems, but fortunately rather slowly (from F=0.25 at N=4 to F=0.16 at N=8). If the total amount of noise is kept constant, that is, Γ∝1/N, the annealing is found to profit from larger system sizes, since a quantum jump at spin i is unlikely to affect the sign of

. The results for a glassy instance (δ=2π × 198 kHz at ωz=2π × 700 kHz) are summarized in Table 1 for N=4, 6, 8. The noise rate is chosen such that on average one quantum jump occurs in the system with four ions, while accordingly the system with eight ions suffers on average from two such events. In all cases, the annealing produces the correct pattern, F>0. As expected, F decreases for larger systems, but fortunately rather slowly (from F=0.25 at N=4 to F=0.16 at N=8). If the total amount of noise is kept constant, that is, Γ∝1/N, the annealing is found to profit from larger system sizes, since a quantum jump at spin i is unlikely to affect the sign of  for j≠i. We note that the spin values produced by the Monte Carlo wave-function method cannot be described by a normal distribution. Importantly, the peak of each distribution, roughly coinciding with its median, is barely affected by the noise. Thus, larger fidelities can be obtained from the median rather than from the arithmetic mean of

for j≠i. We note that the spin values produced by the Monte Carlo wave-function method cannot be described by a normal distribution. Importantly, the peak of each distribution, roughly coinciding with its median, is barely affected by the noise. Thus, larger fidelities can be obtained from the median rather than from the arithmetic mean of  .

.

Spin pattern in the quantum Mattis model

The quantum annealing discussed above exploits quantum effects to extract information encoded in the classical model. Now we search for information which is encoded in the quantum, but not in the classical model. Therefore, we focus on the ferromagnetic Mattis model, which in the classical case keeps a binary memory of a spin pattern, that is, of N bits. Our considerations can also be generalized to the Hopfield model1, which memorizes multiple patterns. We will show how quantum effects can increase the amount of information encoded by these models.

Recall that in the classical case, the spin pattern was defined by a resonant mode in terms of the sign of each component. In the quantum case, however, one cannot simply replace classical spins by quantum averages,  . Even in a weak transverse field B, this quantity vanishes due to the Z2 symmetry, σx→−σx. Instead, the pattern is reflected by

. Even in a weak transverse field B, this quantity vanishes due to the Z2 symmetry, σx→−σx. Instead, the pattern is reflected by  , where

, where  and

and  are the ground and first excited state. For small B, we find numerically sign(λi)=sign(ξim). For large B, the stronger relation λi=ξim holds approximately, see Fig. 7. Thus, the former binary memory has become real-valued.

are the ground and first excited state. For small B, we find numerically sign(λi)=sign(ξim). For large B, the stronger relation λi=ξim holds approximately, see Fig. 7. Thus, the former binary memory has become real-valued.

The spin expectation values λi approach the real values of the mode vector ξim when a sufficiently strong transverse magnetic field B is present. The shown data was obtained from the effective spin Hamiltonian for N=6 ions in the ferromagnetic regime, δ=2π × 143 kHz. Deviations from the equality λi=ξim are smaller than 0.04.

To show this behaviour, we note that for strong B, the ground state |Ψ1〉 is fully polarized along z, and the first excited state |Ψ2〉 is restricted to the N-dimensional subspace with one spin flipped, that is,  . Within this subspace the Hamiltonian HJ is given by an N × N matrix approximately proportional to

. Within this subspace the Hamiltonian HJ is given by an N × N matrix approximately proportional to  for i≠j, and

for i≠j, and  . Here we neglect all but the m-th mode close to resonance.

. Here we neglect all but the m-th mode close to resonance.

It is easy to see that the vector ξm is a ground state of the matrix −ξimξjm, which differs from  only by the diagonal elements, which approach unity for large N. Thus, the first excited state reads

only by the diagonal elements, which approach unity for large N. Thus, the first excited state reads  , where

, where  denotes the state in which spin i is flipped relatively to all others (in the σz basis). This shows that λi≈ξim, and the small deviations decrease quickly with N.

denotes the state in which spin i is flipped relatively to all others (in the σz basis). This shows that λi≈ξim, and the small deviations decrease quickly with N.

Measuring λi experimentally is possible by full state tomography. The absolute value of λi can be obtained via a simple  measurement. In the limit of strong B-fields we have

measurement. In the limit of strong B-fields we have  .

.

Many applications are known for the classical spin system with couplings defined by spin patterns, reaching from pattern recognition and associative memory in the Hopfield model1 to noise-free coding2,47. Our analysis suggests that patterns given by real numbers could replace patterns of binary variables by exploiting the quantum character of the spins.

Discussion

In summary, our work demonstrates the occurrence of Mattis glass behaviour in spin chains of trapped ions, if the detuning of the spin-phonon coupling is chosen between two resonances. In these regimes, the effective spin system has an exponentially large number of low-energy states, and finding its ground state corresponds to solving a number-partitioning problem. This establishes a direct connection between the properties of a physical system and the solution of a potentially NP-hard problem of computer science. Given the state-of-art in experiments with trapped ions, the physical implementation is feasible: In comparison with the previous experiments with trapped ions10,11,12,13,14, only the detuning of the spin-phonon coupling needs to be adjusted. Differently from other approaches to spin glass physics, our scheme does not require any disorder. In its most natural implementation, parity symmetry allows one to analytically determine the ground state. Different ways to break this symmetry can be implemented to increase the complexity of the problem.

The ion chain then becomes an ideal test ground for applying quantum simulation strategies to solve computationally complex problems. By applying a transverse field to the ions, quantum annealing from a paramagnet to the glassy ground state is possible. The ionic system may be used to benchmark quantum annealing, which has become a subject of very lively and controversial debate since the launch of the D-Wave computers7,8. Exact calculations for small systems (N=6) and approximative calculations for larger system (N=22) demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed quantum annealing, and suggest a polynomial scaling of the annealing time. Accordingly, this approach may offer the sought-after quantum speed-up. In view of sizes of 30 and more ions already trapped in recent experiments (cf., ref. 48), a realization of our proposal could not only confirm our semi-classical results, but also go beyond the sizes considered here.

Finally, resonant coupling to multiple modes opens an avenue to neural network models, where a finite number of patterns is memorized by couplings to different phonon modes. Quantum features can increase the memory of such networks from binary to real-valued numbers. It will be subject of future studies to work out the possible benefits which quantum neural networks may establish for information processing purposes.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Graß, T. et al. Quantum annealing for the number-partitioning problem using a tunable spin glass of ions. Nat. Commun. 7:11524 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11524 (2016).

References

Hopfield, J. J. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 79, 2554–2558 (1982).

Nishimori, H. International Series of Monographs on Physics Clarendon Press (2001).

Barahona, F. On the computational complexity of Ising spin glass models. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 15, 3241–3253 (1982).

Lucas, A. Ising formulations of many NP problems. Front. Phys. 2, 5 (2014).

Sherrington, D. & Kirkpatrick, S. Solvable model of a spin-glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 1792–1796 (1975).

Mézard, M., Parisi, G., Sourlas, N., Toulouse, G. & Virasoro, M. Replica symmetry breaking and the nature of the spin glass phase. J. Phys. France 45, 843–854 (1984).

Rønnow, T. F. et al. Defining and detecting quantum speedup. Science 345, 420–424 (2014).

Katzgraber, H. G., Hamze, F. & Andrist, R. S. Glassy chimeras could be blind to quantum speedup: designing better benchmarks for quantum annealing machines. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021008 (2014).

Denchev, V. S. et al. What is the Computational Value of Finite Range Tunneling? Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.02206 (2015).

Friedenauer, A., Schmitz, H., Glueckert, J. T., Porras, D. & Schaetz, T. Simulating a quantum magnet with trapped ions. Nat. Phys. 4, 757–761 (2008).

Kim, K. et al. Entanglement and tunable spin-spin couplings between trapped ions using multiple transverse modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 120502 (2009).

Kim, K. et al. Quantum simulation of frustrated Ising spins with trapped ions. Nature 465, 590–593 (2010).

Britton, J. W. et al. Engineered two-dimensional Ising interactions in a trapped-ion quantum simulator with hundreds of spins. Nature 484, 489–492 (2012).

Jurcevic, P. et al. Quasiparticle engineering and entanglement propagation in a quantum many-body system. Nature 511, 202–205 (2014).

Richerme, P. et al. Non-local propagation of correlations in quantum systems with long-range interactions. Nature 511, 198–201 (2014).

Porras, D. & Cirac, J. I. Effective quantum spin systems with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 207901 (2004).

Mintert, F. & Wunderlich, C. Ion-Trap quantum logic using long-wavelength radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 257904 (2001).

Schmitz, H. et al. The ‘arch’ of simulating quantum spin systems with trapped ions. Appl. Phys. B 95, 195–203 (2009).

Joseph Wang, C.-C. & Freericks, J. K. Intrinsic phonon effects on analog quantum simulators with ultracold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032329 (2012).

Pons, M. et al. Trapped ion chain as a neural network: error resistant quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 023003 (2007).

Strack, P. & Sachdev, S. Dicke quantum spin glass of atoms and photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 277202 (2011).

Gopalakrishnan, S., Lev, B. L. & Goldbart, P. M. Frustration and glassiness in spin models with cavity-mediated interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 277201 (2011).

Rotondo, P., Lagomarsino, M. C. & Viola, G. Dicke simulators with emergent collective quantum computational abilities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 143601 (2015).

Stein, D. L. & Newman, C. M. Spin glasses: old and new complexity. Complex Syst. 20, 115–126 (2011).

Stein, D. L. & Newman, C. M. Spin Glasses and Complexity Princeton University Press (2013).

Moore, M. A., Bokil, H. & Drossel, B. Evidence for the droplet picture of spin glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4252 (1998).

Aspelmeier, T. et al. Finite-size critical scaling in Ising spin glasses in the mean-field regime. Phys. Rev. E 93, 032123 (2016).

Amit, D. J., Gutfreund, H. & Sompolinsky, H. Storing infinite numbers of patterns in a spin-glass model of neural networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1530–1533 (1985).

Amit, D. J., Gutfreund, H. & Sompolinsky, H. Statistical mechanics of neural networks near saturation. Ann. Phys. 173, 30–67 (1987).

Parisi, G. The order parameter for spin glasses: a function on the interval 0-1. J. Phys. A (Math. Gen.) 13, 1101–1112 (1980).

Mezard, M., Parisi, G. & Virasoro, M. A. Spin glass theory and beyond World Scientific (1987).

Vincent, E. Lecture Notes in Physics Springer (2007).

Fisher, D. S. & Huse, D. A. Ordered phase of short-range ising spin-glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett 56, 1601 (1986).

Daniel, S. F. & David, A. H. Equilibrium behavior of the spin-glass ordered phase. Phys. Rev. B 38, 386 (1988).

Lefloch, F., Hammann, J., Ocio, M. & Vincent, E. Can aging phenomena discriminate between the droplet model and a hierarchical description in spin glasses? EPL 18, 647 (1992).

Mattis, D. Solvable spin systems with random interactions. Phys. Lett. A 56, 421–422 (1976).

Mertens, S. Phase transition in the number partitioning problem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4281 (1998).

Mertens, S. The Easiest Hard Problem: Number Partitioning. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/condmat/0310317 (2003).

Nevado, P. & Porras, D. Hidden frustrated interactions and quantum annealing in trapped ion spin-phonon chains. Phys. Rev. A 93, 013625 (2016).

Steane, A. M. The ion trap quantum information processor. Appl. Phys. B 64, 623–643 (1997).

James, D. F. V. Quantum dynamics of cold trapped ions with application to quantum computation. Appl. Phys. B 66, 181–190 (1998).

Bermudez, A., Schaetz, T. & Porras, D. Photon-assisted-tunneling toolbox for quantum simulations in ion traps. New J. Phys. 14, 053049 (2012).

Hauke, P., Bonnes, L., Heyl, M. & Lechner, W. Probing entanglement in adiabatic quantum optimization with trapped ions. Front. Phys. 3, 21 (2015).

Korenblit, S. et al. Quantum simulation of spin models on an arbitrary lattice with trapped ions. New J. Phys. 14, 095024 (2012).

Park, J. H. & Light, J. C. Unitary quantum time evolution by iterative lanczos reduction. J. Chem. Phys. 86, 5870–5876 (1986).

Mølmer, K., Castin, Y. & Dalibard, J. Monte Carlo wave-function method in quantum optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 10, 524–538 (1993).

Sourlas, N. Spin-glass models as error-correcting codes. Nature 339, 693–695 (1989).

Ramm, M., Pruttivarasin, T. & Häffner, H. Energy transport in trapped ion chains. New J. Phys. 16, 063062 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Acín, R. Augusiak, A. Bermudez, J. Tura, P. Rotondo, L. Santos and P. Wittek for discussions. We acknowledge financial support from EU grants OSYRIS (ERC-2013-AdG Grant No. 339106), SIQS (FP7-ICT-2011-9 No. 600645), QUIC (H2020-FETPROACT-2014 No. 641122), EQuaM (FP7/2007-2013 Grant No. 323714), Spanish MINECO grants (FOQUS FIS2013-46768-P, FIS2014-54672-P), Severo Ochoa grant (SEV-2015-0522), Generalitat de Catalunya (2014 SGR 401, 2014 SGR 874 and SGR 875), the Maria de Maeztu grant (MDM-2014-0369) and Fundació Cellex. B.J.-D. is supported by the Ramon y Cajal program, and C.G. by MPQ-ICFO, ICFOnest+ (FP7-PEOPLE-2013-COFUND) and by the European Union’s Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowships (IF-EF) programme (GA 700140).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptual design of the quantum simulation, discussion and interpretation of results, and the writing of the manuscript. Exact numerical calculations were performed by T.G. Semi-classical calculations were done by B.J.-D. and D.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Graß, T., Raventós, D., Juliá-Díaz, B. et al. Quantum annealing for the number-partitioning problem using a tunable spin glass of ions. Nat Commun 7, 11524 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11524

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11524

This article is cited by

-

Antiferromagnetic spatial photonic Ising machine through optoelectronic correlation computing

Communications Physics (2021)

-

A double-slit proposal for quantum annealing

npj Quantum Information (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.