Abstract

Oxygen depletion in the upper ocean is commonly associated with poor ventilation and storage of respired carbon, potentially linked to atmospheric CO2 levels. Iodine to calcium ratios (I/Ca) in recent planktonic foraminifera suggest that values less than ∼2.5 μmol mol−1 indicate the presence of O2-depleted water. Here we apply this proxy to estimate past dissolved oxygen concentrations in the near surface waters of the currently well-oxygenated Southern Ocean, which played a critical role in carbon sequestration during glacial times. A down-core planktonic I/Ca record from south of the Antarctic Polar Front (APF) suggests that minimum O2 concentrations in the upper ocean fell below 70 μmol kg−1 during the last two glacial periods, indicating persistent glacial O2 depletion at the heart of the carbon engine of the Earth’s climate system. These new estimates of past ocean oxygenation variability may assist in resolving mechanisms responsible for the much-debated ice-age atmospheric CO2 decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Southern Ocean is widely considered to be critical to global nutrient and carbon cycling, including over glacial–interglacial time scales1. As an area of incomplete nutrient utilization, it is a major source of CO2 to the atmosphere today2. At present, old (CO2− and nutrient-rich and relatively O2−depleted) deep waters upwell along most of the Antarctic continental margin3,4 (Fig. 1), release CO2 into, and recharge O2 from surface waters before they down-well in distinct areas, such as the Weddell and Ross seas, to form Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW). In the glacial Southern Ocean, strengthening of the biological pump due to enhanced iron supply5,6, increased stratification7, and expanded sea–ice cover8, were among the dominant players in reducing atmospheric CO2 by ∼90 p.p.m.V. Each of these mechanisms could counterbalance the increased O2 solubility due to lower glacial temperatures, leading to a reduction in the O2 concentration of the seawater. Since the Southern Ocean is thought to have reduced its CO2 leakage during glacial periods1, it provides an ideal location to search for evidence of deoxygenation linked to CO2 sequestration in the upper ocean.

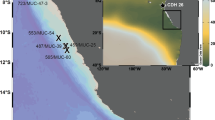

Dissolved oxygen concentrations showing major water masses50 and boundaries, average modern summer (SSI) and winter (WSI) sea–ice extent62, and core site PS2547/TC493. The locations of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) fronts are marked as SB, Southern Boundary of the ACC; SACCF, Southern ACC Front; APF, Antarctic Polar Front; SAF, Sub-Antarctic Front. AABW, Antarctic Bottom Water; AAIW, Antarctic Intermediate Water; AASW, Antarctic Surface Water; CDW, Circumpolar Deep Water; PDW, Pacific Deep Water. This graph is generated in Ocean Data View, using the Southern Ocean Atlas data set63.

During the last glacial period, deep waters surrounding Antarctica were less ventilated, and older than today (relative to the atmosphere)9. A recent quantitative O2 proxy study based on benthic foraminiferal δ13C indicates that decreased ventilation linked to a reorganization of glacial ocean circulation and a strengthened global biological pump significantly enhanced the ocean storage of respired carbon in the deep North Atlantic10. Early box-models hypothesized very low-oxygen levels in the high latitude Southern Ocean11,12. Proxies did not paint a clear picture for bottom-water O2 concentrations in the glacial Southern Ocean13. Only a few studies on marine sediment cores south of the APF have found evidence for substantially lowered bottom water O2 concentrations. There, authigenic uranium concentrations were elevated in sediments deposited during glacial Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 2 and 6 (refs 14, 15). By contrast, another study highlighted a transient stagnation event during the early stage of the last interglacial (MIS 5e)16.

Bottom water or porewater redox proxies cannot capture upper ocean O2 levels far from the continental shelf, so there is scant constraint on upper ocean oxygenation conditions in vast tracts of the open ocean13. A novel proxy, the I/Ca composition of marine carbonates, especially planktonic and benthic foraminiferal tests, has demonstrated its potential to reconstruct paleo-oxygenation levels in both the upper ocean17,18,19,20 and bottom waters21, respectively. The thermodynamically stable forms of iodine in seawater are iodate (IO3−) and iodide (I−)22. The total concentrations of IO3− and I− are relatively uniform in the world ocean at around 0.45 μmol l−1 due to the residence time of ∼300 kyr (ref. 23), supported by a more recent compilation of iodine concentrations in global rivers24. Therefore, the total iodine concentration in the global ocean likely remained invariant over the duration of a glacial termination (∼6 kyr).

Iodate is taken up by marine organisms as a micronutrient in surface waters25, but its concentration does not increase during the aging of deep waters26,27, in contrast to those of the major nutrients nitrate and phosphate, probably due to the low I/Corg ratio of plankton25. Iodine speciation is strongly redox sensitive. IO3− is completely converted to I− when oxygen is depleted28. Because IO3− is the only chemical form of iodine that is incorporated into the structure of carbonate17, calcareous tests precipitated closer to an oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) will record lower I/Ca and vice versa. An OMZ is defined by O2<20 μmol kg−1 in the Pacific Ocean and O2<50 μmol kg−1 in the Atlantic Ocean29.

In this paper, we use recent planktonic foraminifera and modern water column data to establish typical I/Ca values for the presence of an OMZ or O2-depleted water. On the basis of this proxy development, the down-core record of planktonic foraminifera I/Ca obtained at site TC493/PS2547 indicates the persistent presence of oxygen-depletion in the upper waters of high latitude Southern Ocean during the last two glacial periods.

Results

Site selection

We measured I/Ca values on eleven planktonic foraminiferal species in modern to Holocene samples, and in one sample from a previous interglacial (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). We chose sites from well-oxygenated areas (for example, the North and sub-Antarctic South Atlantic), and sites located beneath OMZs, including Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Sites 658, 709, 720 (Site 720: last interglacial samples), 849 and 1242. First, we use these data to further establish the foundations of the I/Ca proxy. Subsequently, we focus on an I/Ca down-core record on Neogloboquadrina pachyderma sinistral deposited during the last two glacial cycles in two sediment cores (PS2547 and TC493) recovered from the same location (71°09′ S, 119°55′ W, water depth 2,096 m) on a seamount in the Amundsen Sea (Fig. 1)30. The excellent carbonate preservation at this site30 provides a unique window to reconstruct past upper ocean conditions south of the APF. Site TC493/PS2547 is currently bathed by Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW), which is overlain by a layer of Antarctic Surface Water (AASW), or Winter Water31,32,33, and is located on the edge of the average modern summer sea–ice limit34 (Fig. 1). During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), the sea–ice boundaries within the Southern Ocean shifted significantly northwards35,36. Thus, it is highly likely that site TC493/PS2547 was located within the permanent sea–ice zone during past glacial periods34.

Age model and glacial polynyas

The sediments of core TC493/PS2547 consist mainly of foraminiferal ooze and sandy mud, with N. pachyderma (s) tests forming the primary carbonate component30. The age model of the record is based on magnetostratigraphy combined with benthic foraminiferal (Cibicides cf. wuellerstorfi) oxygen isotope (δ18O) stratigraphy30, tuned to the global benthic δ18O stack37. Continuous deposition of foraminifera30 indicates at least episodic opening of polynyas during glacial periods34, because of its seamount location38,39. This scenario is consistent with the occurrence of the benthic foraminifera species Epistominella exigua, which is adapted to highly episodic phytodetritus supply40.

I/Ca in foraminifera

I/Ca values in the modern and late Holocene samples are lower than ∼2.5 μmol mol−1 at sites with O2 minima <70 μmol kg−1 in the upper ocean (0–500 m) (Fig. 2a). In contrast, recent planktonic foraminifera at sites with O2 minima >100 μmol kg−1 have I/Ca >4 μmol mol−1, regardless of species (Fig. 2a). At site TC493/PS2547, the N. pachyderma (s) I/Ca ratio is high (5–7 μmol mol−1) during the Holocene and MIS 5 relative to the lowest values (<2 μmol mol−1) during glacial MIS 2 and 6 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2).

(a) Modern and late Holocene I/Ca in planktonic foraminiferal tests versus minimum O2 concentrations in the upper 500 m of the water column (Note: I/Ca at Site 720 is from a MIS 5 sample). Error bars for y axis indicate the s.d. (1 s.d.) of triplicate measurements. Blue squares show down-core interglacial (IG) I/Ca data on N. pachyderma (s) from site TC493/PS2547 plotted against minimum O2 concentrations in the modern water column, indicating well-oxygenated conditions. I/Ca for glacial N. pachyderma (s) tests are marked as red squares, indicating O2 depletion. (b) Compilation of modern ocean surface water IO3− concentrations compared with minimum O2 concentrations26,27,28,47,48,64,65,66,67,68,69. Brown dashed line indicates the surface water IO3− concentration of ∼0.25 μmol l−1 as a threshold value for differentiating OMZ-type and normal open ocean type of IO3− depth profiles. (c) O2 depth profiles. Yellow shading marks 20–70 μmol kg−1 O2 concentration as the threshold for complete iodate reduction. (d) IO3− depth profiles at OMZ sites from the Eastern Equatorial Pacific (EEP)28 and the Arabian Sea (station N8)48 and at a well-oxygenated high-latitude site near the Weddell Sea (station PS71/179–1)54.

(a,b) Stable carbon and oxygen isotopes measured on benthic (C. cf. wuellerstorfi) and planktonic (N. pachyderma) foraminiferal tests30. It is well documented that δ13C of N. pachyderma (s) is offset by −1.0‰ south of the APF49 and the values plotted here are uncorrected. (c) Atmospheric pCO2 record at EPICA Dome C is plotted for comparison, with dashed line indicating the long-term mean value of CO2 (50–270 ka) following Luethi et al.56. (d) I/Ca measured on N. pachyderma (s) tests from cores PS2547 and TC493. (e) Bulk sediment CaCO3 content from PS2547. Grey columns show the abundance of the benthic foraminifera E. exigua as number of tests per cm3 in core PS2547. Yellow shading highlights peak interglacial periods (including deglaciations), and blue shading marks glacial maxima and cooling intervals.

Discussion

A tremendous amount of work has been devoted to developing foraminiferal proxies for temperature and pH, using global calibrations derived from core-top samples (for example, the Mg/Ca seawater temperature proxy41). Low I/Ca ratios of planktonic foraminifera unambiguously reveal the presence of low-oxygen waters, but a global calibration approach cannot establish planktonic foraminifera I/Ca as a linearly quantitative proxy for the continuum of dissolved O2 concentration. Due to the stepwise nature of redox reactions42, quantitative IO3− reduction does not occur before the dissolved oxygen is depleted to a certain threshold value, triggering nitrate reduction43. IO3− concentrations at water depths matching planktonic foraminiferal habitats are often not in equilibrium with the in situ O2 concentrations, and O2 contents which are sufficiently low to initiate major IO3− reduction may be detrimental to many species44. Instead, the I/Ca (recording the in situ IO3− concentration) is determined by the depth habitat of the foraminifera and the upper ocean IO3− mixing gradient. This mixing gradient is largely controlled by the surface water IO3− concentration and the depth of the IO3− reduction zone28. Nonetheless, a planktonic foraminifera proxy that semi-quantitatively approximates dissolved O2 concentrations, indicative of the presence of an OMZ, can still be highly valuable for the paleoceanography community.

Before interpreting the down-core record from site TC493/PS2547, we identify the characteristic I/Ca signals for modern OMZs. IO3− depth profiles in the open ocean generally fall into two types (Fig. 2d): (1) the OMZ-type, with low surface water values and near-zero subsurface values in the OMZ; and (2) the normal open ocean type (for example, in a well-oxygenated water column), with relatively high surface water values and even higher subsurface values. A threshold O2 concentration will cause complete IO3− reduction in the subsurface, and there may be a surface water IO3− threshold concentration below which complete IO3− reduction is likely to happen in the water column. Combined with modern water column IO3− and O2 data, the I/Ca values measured on modern and late Holocene planktonic foraminifera consistently indicate that I/Ca <2.5 μmol mol−1 is equivalent to a surface water IO3− concentration of <0.25 μmol l−1, thus providing a marker for the presence of oxygen-depleted water with a subsurface O2 concentration <20–70 μmol kg−1 (Fig. 2a–c).

Modern surface water IO3− concentrations are influenced by productivity and the presence of a subsurface OMZ25,28. To visualize this relationship, we compiled surface water IO3− concentrations from the literature and plotted them against the minimum O2 concentrations in the subsurface water (Fig. 2b). The IO3− concentration broadly increases with the minimum O2 concentration when the surface water IO3− concentration is >0.25 μmol l−1 (Fig. 2b). This correlation is likely a reflection of surface productivity versus subsurface respiration, because lower productivity leads to lower iodine uptake in surface water and less oxygen consumption by subsurface organic matter decomposition. In areas with a strong OMZ and near-zero O2 values, the surface water IO3− concentrations are below 0.25 μmol l−1 (Fig. 2b). A partition coefficient Kd (Kd=[I/Ca]/[IO3−] with units of [μmol mol−1]/[μmol l−1]) of ∼10 was reported from abiological calcite synthesis experiments17,20. Using this Kd value, an IO3− concentration <∼0.25 μmol l−1 results in I/Ca values <∼2.5 μmol mol−1 in calcite. This estimate is consistent with modern I/Ca at OMZ Sites 658, 849 and 1242, as well as the last interglacial I/Ca value at Site 720 (Fig. 2a). Therefore, a surface water I/Ca value <2.5 μmol mol−1 indicates that a pronounced subsurface O2 minimum exerted the dominant control on the upper ocean IO3− profile. This I/Ca threshold value does not seem to depend on foraminiferal species (Fig. 2a).

The O2 threshold for maintaining an OMZ-type IO3− profile is useful for the paleoceanographic application of the planktonic I/Ca proxy. At O2 concentrations <20 μmol kg−1, microbial processes become dominant29, and IO3− likely would be completely reduced to I− since the reaction is biologically mediated45 (for example, ODP Sites 1242, 720 and 849 in Fig. 2a,c). ODP Site 658 is located at the northern edge of a shallow pocket of distinctively low-oxygen water with mean O2 concentrations of ∼70 μmol kg−1 in the upper 200 m (ref. 46), which may be sufficiently low to generate an OMZ-type iodate profile. Three species of planktonic foraminifera analysed at ODP Site 1242 show exceptionally low I/Ca ratios around 0.5 μmol mol−1, corresponding to an IO3− concentration of ∼0.05 μmol l−1. Such a low IO3− concentration is comparable to that reported for a location where an extreme hypoxic event occurred47. Moreover, this low IO3− concentration implies that IO3− reduction should occur shallower than at Site 849 and at two sites with classic OMZ-type IO3− profiles (Eastern Equatorial Pacific28 and Arabian Sea48; Fig. 2c). A comparison of the O2 profiles of these sites reveals that the O2 threshold needs to be >50 μmol kg−1 to achieve a shallower IO3− reduction at Site 1242. Therefore, we suggest that I/Ca values lower than ∼2.5 μmol mol−1 indicate O2 minima <20–70 μmol l−1. This O2 range cannot be further narrowed down with the available information, and we refer to this range as the O2 threshold for an OMZ-type IO3− profile. However, the threshold behaviour of IO3− reduction (relative to O2) in subsurface waters does not necessarily lead to step changes in down-core records of planktonic I/Ca. This is because planktonic foraminifera typically record the IO3− mixing gradient in the top part of water column, above the O2-depleted zone where rapid step changes in IO3− concentrations occur. Low planktonic I/Ca values may be driven by shoaling of O2-depleted water, and/or by increasing productivity, both of which could change gradually over time.

The available data from modern and late Holocene planktonic foraminifera suggest that the I/Ca ratio acts as a robust (paleo-) proxy for determining the signature of O2-depletion in the upper ocean (Fig. 2). At site TC493/PS2547, I/Ca was high (5–7 μmol mol−1) during the Holocene and interglacial MIS 5 when compared with the lowest values (<2 μmol mol−1) characterizing peak glacial periods MIS 2 and 6 (Fig. 3). Changes in salinity, temperature and foraminiferal habitat, most likely, are not the main drivers for this record (Supplementary Discussion). The glacial I/Ca values of N. pachyderma (s) are best explained by the presence of a water mass with a dissolved O2 content <70 μmol kg−1 close to, i.e., above or near, this site (Figs 2 and 3). We reiterate that the low I/Ca does not necessarily imply O2-depleted seawater within the foraminiferal habitat.

At present, CDW wells up to a water depth of approximately 250–300 m in the Amundsen Sea31 and has O2 concentrations notably lower than the top 200 m of the water column (Fig. 2c). Although the interpretation of absolute values of planktonic δ13C is far from straightforward in the seasonal ice zone (for example, disequilibrium from seawater49), it is reasonable to assume that CDW had a strong influence on the local water column during glacial periods, as its upwelling along the continental margin was probably responsible for the opening of the glacial polynyas. The CDW upwelling at site TC493/PS2547 today partly originates from Pacific Deep Water (PDW) moving southward from the equator, with a low-oxygen and high nutrient signature (Fig. 1)50,51. δ30Si data from fossil diatoms and sponges indicate higher silicic acid concentrations in the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean during the LGM, which further imply that either the southward transport of PDW was more efficient or PDW was less ventilated than today52. So glacial CDW was likely more O2 depleted than during interglacials, and upwelling of this water contributed to the glacial I/Ca signal at site TC493/PS2547.

The oxidation of I− to IO3− is thought to take from a few months up to 40 years53. Long-distance transport of well-oxygenated deep water with low IO3− concentrations (<0.25 μmol l−1) has not been documented in the modern ocean, but this scenario should be tested with further work on I− oxidation kinetics. Today our site is bathed in CDW transported from a Pacific OMZ and the interglacial I/Ca values at site TC493/PS2547 do not show any remnant signal of the OMZ from the Pacific Ocean. On the basis of the knowledge about iodine speciation change in modern ocean, we interpret the observed glacial I/Ca values as a local signal, in principle, indicating the presence of a water mass with low O2 and low IO3− vertically or horizontally close to the planktonic foraminiferal habitat.

In the setting of site TC493/PS2547 a coherent conceptual model for N. pachyderma (s) recording the presence/absence of O2-depletion needs to integrate changes in productivity, sea–ice extent and the opening/closing of polynyas on time scales of glacial to seasonal cycles (Fig. 4). Although the polynyas complicate the interpretation of the proxy data, their presence arguably provides the only window for sufficient accumulation of planktonic microfossils to record upper ocean conditions during glacial periods at such high latitudes.

The modern O2 profile at site TC493/PS2547 is defined by equilibration with the atmosphere at 0–250 m, and CDW influence below 250 m, as shown by the distinctively low O2 concentrations (Fig. 2c). With O2 above the threshold for complete IO3− reduction in the entire water column, the IO3− profile at site TC493/PS2547 should be similar to those at other high latitude locations, for example, site PS71/179–1 at 69°31′ S and 0°3′ W in the Weddell Sea54 (Fig. 2d). An interglacial scenario of relatively high seasonal productivity, high O2 and surface water IO3− (>0.3 μmol l−1) concentrations (Fig. 4a), is well described for the modern Atlantic sector of Southern Ocean54.

Relative to the interglacial periods, the Southern Ocean experienced expanded sea–ice cover during glacial periods, and was less ventilated9,36. A more dynamic seasonal sea–ice cycle during ice ages would have increased water column stratification. Increased winter sea–ice formation (spatially and volumetrically) may have generated waters dense enough to sink ultimately to the bottom of the ocean55. On the other hand, melting of thicker sea ice during glacial-time summers in the seasonal sea–ice zone would have strengthened the halocline (not considering the influence of polynyas). So, the glacial seasonal stratification was likely stronger than today. These factors overall should have lowered the glacial O2 concentrations in the Southern Ocean (Fig. 4b). At site TC493/PS2547, glacial I/Ca demonstrate that the IO3− profile was OMZ-like with complete IO3− reduction near the foraminiferal habitat (Fig. 2d). However, the dynamics of polynyas must be considered when interpreting the location of the low O2 water mass, and the means by which the signal was recorded by N. pachyderma (s).

Without a polynya above site TC493/PS2547, glacial phytoplankton productivity under perennial sea–ice cover would have been relatively low due to the scarcity of light34, and planktonic foraminifera depending on algae could not flourish. The water column would have been relatively poorly ventilated and strongly stratified during these times, creating the ideal environment for developing low O2 conditions and an OMZ-type IO3− profile (Fig. 4b). The episodic opening of a polynya re-established primary production (mainly by diatoms) and thus a planktonic foraminiferal habitat, vertical mixing and oxygenation in, at least, the uppermost part of the water column (Fig. 4c). While overall glacial-time production was reduced30,34, the planktonic foraminifera preserved in the glacial sediments probably recorded transient I/Ca changes in the water column associated with polynya-induced peaks in glacial productivity. Modern open ocean productivity pulses do not lower IO3− concentrations to <0.25 μmol l−1 in oxygenated water (Supplementary Discussion)54, thus the glacial I/Ca signal is most likely driven by changes in O2 and not productivity.

The likely short-lived nature of glacial polynyas makes it difficult to envisage that very brief plankton blooms alone could produce a utilization-driven O2 depletion in a cold, well-oxygenated Southern Ocean. For the same reason, it is difficult to imagine that the vertical mixing cells restricted by the size of the polynya could rapidly oxygenate voluminous nearby waters outside of the polynya, if most of the sea–ice covered areas were O2-depleted. The more likely scenario is that the O2 concentrations in the deep and abyssal Southern Ocean were generally lower during glacial periods than during interglacial periods. Upwelling of a more O2-depleted CDW in the generally stratified upper ocean was mainly responsible for the IO3− reduction at site TC493/PS2547 (Fig. 4b), while the episodic opening of polynyas created habitable conditions for planktonic foraminifera to record the deoxygenation in the upper ocean (Fig. 4c). We suggest that the I/Ca proxy should be used as a local proxy, in principle. However, it is probably a reasonable speculation that this record (Fig. 3) shows oxygenation changes integrated over a regional volume of water (e.g. CDW).

The timing of glacial deoxygenation and deglacial reoxygenation at site PS2547 shows potential linkages to global climate changes (Fig. 3). The appearance of OMZ-type I/Ca values (<∼2.5 μmol mol−1) during past glacial periods coincided with the lowering in atmospheric pCO2 level below the long-term mean value56. Identical timing was reported for a strongly stratified Antarctic Zone coincident with pCO2 decrease under the same threshold value (225 p.p.m.) in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean57. Stronger stratification may be the common driving force for the productivity change (ODP Site 1094) and oxygenation change (PS2547/TC493) in the Antarctic zone. Furthermore, during the last interglacial period, the recovery of N. pachyderma (s) I/Ca values is offset from the δ18O trend, with peak I/Ca occurring about 10 kyr after the peak δ18O (Fig. 3), an observation worthy of future investigation.

Our I/Ca results build on other evidence52,58,59 to make a stronger case for lower oxygen concentrations in CDW (and very likely PDW) during glacial periods. Altogether with the reconstructed O2 content of deep waters in the glacial North Atlantic10, these observations seem to allude to large scale deoxygenation in the glacial global ocean interior60. Future work providing quantitative reconstructions of bottom water O2 concentrations in the Southern Ocean, especially south of the APF, and in other major ocean basins will shed new light on the mechanisms of sequestering atmospheric CO2 during ice ages.

Methods

Foraminifera cleaning

Sediments were sampled from the split core sections and wet sieved. Approximately 40 tests of N. pachyderma sinistral were picked from the 200–250 μm size fraction of each sample. The cleaning procedure followed the Mg/Ca protocol of Barker et al.61. Cleaned glass slides were used to gently crack open all chambers. Clay particles were removed in an ultrasonic water bath. After adding NaOH-buffered 1% H2O2 solutions the samples were heated in boiling water for 10–20 min to remove organic matter. Calcareous microfossils were then thoroughly rinsed with de-ionized water. Reductive cleaning was not applied because contribution of iodine from Mn-oxides is deemed negligible19.

ICP-MS measurements

The cleaned samples were dissolved in 3% nitric acid, and diluted to solutions with 50 p.p.m. Ca for analyses. Iodine calibration standards were freshly prepared also with 50 p.p.m. Ca. 0.5% tertiary amine solution (Spectrasol, CFA-C) was added to stabilize iodine within a few minutes after the sample dissolution. The measurements were performed immediately after that to minimize potential iodine loss. The sensitivity of iodine was tuned to above 80 kcps for a 1 p.p.b. standard. The precision for 127I is typically better than 1%. The long-term accuracy is guaranteed by frequently repeated analyses of the reference material JCp-1 (ref. 17). The detection limit of I/Ca is on the order of 0.1 μmol mol−1. The I/Ca measurements were performed using a quadrupole ICP-MS (Bruker M90) at Syracuse University.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Lu, Z. et al. Oxygen depletion recorded in upper waters of the glacial Southern Ocean. Nat. Commun. 7:11146 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11146 (2016).

Change history

26 April 2016

In Fig. 3 of this Article, data in panel ‘a’ were inadvertently partially obscured during the production process. The correct version of Fig. 3 now appears in the PDF and HTML versions of the Article.

References

Sigman, D. M., Hain, M. P. & Haug, G. H. The polar ocean and glacial cycles in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Nature 466, 47–55 (2010).

Marinov, I., Gnanadesikan, A., Toggweiler, J. R. & Sarmiento, J. L. The Southern Ocean biogeochemical divide. Nature 441, 964–967 (2006).

Orsi, A. H., Whitworth, T. & Nowlin, W. D. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep Sea Res I 42, 641–673 (1995).

Schmidtko, S., Heywood, K. J., Thompson, A. F. & Aoki, S. Multidecadal warming of Antarctic waters. Science 346, 1227–1231 (2014).

Martin, J. H. GLACIAL-interglacial CO2 change: the iron hypothesis. Paleoceanography 5, 1–13 (1990).

Martinez-Garcia, A. et al. Iron fertilization of the subantarctic ocean during the last ice age. Science 343, 1347–1350 (2014).

Toggweiler, J. R. Variation of atmospheric CO2 by ventilation of the ocean’s deepest water. Paleoceanography 14, 571–588 (1999).

Stephens, B. B. & Keeling, R. F. The influence of Antarctic sea ice on glacial-interglacial CO2 variations. Nature 404, 171–174 (2000).

Skinner, L. C., Fallon, S., Waelbroeck, C., Michel, E. & Barker, S. Ventilation of the deep southern ocean and deglacial CO2 rise. Science 328, 1147–1151 (2010).

Hoogakker, B. A. A., Elderfield, H., Schmiedl, G., McCave, I. N. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Glacial-interglacial changes in bottom-water oxygen content on the Portuguese margin. Nat. Geosci. 8, 40–43 (2015).

Knox, F. & McElroy, M. B. Changes in atmospheric CO2 - influence of the marine biota at high-latitude. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 89, 4629–4637 (1984).

Archer, D. E. et al. Model sensitivity in the effect of Antarctic sea ice and stratification on atmospheric pCO(2). Paleoceanography 18, (2003).

Jaccard, S. L. & Galbraith, E. D. Large climate-driven changes of oceanic oxygen concentrations during the last deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 5, 151–156 (2012).

Ceccaroni, L. et al. Late Quaternary fluctuations of biogenic component fluxes on the continental slope of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. J. Mar. Syst. 17, 515–525 (1998).

Frank, M. et al. Similar glacial and interglacial export bioproductivity in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean: Multiproxy evidence and implications for glacial atmospheric CO2 . Paleoceanography 15, 642–658 (2000).

Hayes, C. T. et al. A stagnation event in the deep South Atlantic during the last interglacial period. Science 346, 1514–1517 (2014).

Lu, Z., Jenkyns, H. C. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Iodine to calcium ratios in marine carbonate as a paleo-redox proxy during oceanic anoxic events. Geology 38, 1107–1110 (2010).

Hardisty, D. S. et al. An iodine record of Paleoproterozoic surface ocean oxygenation. Geology 42, 619–622 (2014).

Zhou, X. L., Thomas, E., Rickaby, R. E. M., Winguth, A. M. E. & Lu, Z. L. I/Ca evidence for upper ocean deoxygenation during the PETM. Paleoceanography 29, 964–975 (2014).

Zhou, X. et al. Upper ocean oxygenation dynamics from I/Ca ratios during the Cenomanian-Turonian OAE 2. Paleoceanography 30, (2015).

Glock, N., Liebetrau, V. & Eisenhauer, A. I/Ca ratios in benthic foraminifera from the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone: analytical methodology and evaluation as a proxy for redox conditions. Biogeosciences 11, 7077–7095 (2014).

Wong, G. T. F. The marine geochemistry of iodine. Rev. Aquat. Sci. 4, 45–73 (1991).

Broecker, W. S. & Peng, H. T. Tracers in the Sea 690Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory (1982).

Moran, J. E., Oktay, S. D. & Santschi, P. H. Sources of iodine and iodine 129 in rivers. Water Resources Research 38, (2002).

Elderfield, H. & Truesdale, V. W. On the biophilic nature of iodine in seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 50, 105–114 (1980).

Nakayama, E., Kimoto, T., Isshiki, K., Sohrin, Y. & Okazaki, S. Determination and distribution of iodide-iodine and total-Iodine in the North Pacific Ocean - by using a new automated electrochemical method. Mar. Chem. 27, 105–116 (1989).

Waite, T. J., Truesdale, V. W. & Olafsson, J. The distribution of dissolved inorganic iodine in the seas around Iceland. Mar. Chem. 101, 54–67 (2006).

Rue, E. L., Smith, G. J., Cutter, G. A. & Bruland, K. W. The response of trace element redox couples to suboxic conditions in the water column. Deep Sea Res. I 44, 113–134 (1997).

Gilly, W. F., Beman, J. M., Litvin, S. Y. & Robison, B. H. in Annual Review of Marine Science, Annual Review of Marine Science Vol. 5, eds Carlson C. A., Giovannoni S. J. 393–420Annual Reviews (2013).

Hillenbrand, C. D., Futterer, D. K., Grobe, H. & Frederichs, T. No evidence for a Pleistocene collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet from continental margin sediments recovered in the Amundsen Sea. Geo-Mar. Lett. 22, 51–59 (2002).

Wahlin, A. K. et al. Some Implications of ekman layer dynamics for cross-shelf exchange in the amundsen sea. J. Phys. Oceonogr. 42, 1461–1474 (2012).

Nakayama, Y., Schroder, M. & Hellmer, H. H. From circumpolar deep water to the glacial meltwater plume on the eastern Amundsen Shelf. Deep Sea Res. I 77, 50–62 (2013).

Jacobs, S. et al. Getz Ice Shelf melting response to changes in ocean forcing. J Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 4152–4168 (2013).

Thatje, S., Hillenbrand, C. D., Mackensen, A. & Larter, R. Life hung by a thread: Endurance of antarctic fauna in glacial periods. Ecology 89, 682–692 (2008).

Collins, L. G., Pike, J., Allen, C. S. & Hodgson, D. A. High-resolution reconstruction of southwest Atlantic sea-ice and its role in the carbon cycle during marine isotope stages 3 and 2. Paleoceanography 27, (2012).

Gersonde, R., Crosta, X., Abelmann, A. & Armand, L. Sea-surface temperature and sea ice distribution of the Southern Ocean at the EPILOG Last Glacial Maximum—a circum-Antarctic view based on siliceous microfossil records. Quart. Sci. Rev. 24, 869–896 (2005).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic delta O-18 records. Paleoceanography 20, (2005).

Bersch, M., Becker, G. A., Frey, H. & Koltermann, K. P. Topographic effects of the maud rise on the stratification and circulation of the weddell gyre. Deep Sea Res. A 39, 303–331 (1992).

Martin, S. in Encyclopedia of ocean sciences eds Steele H., Turekian K. K., Thorpe S. A. 2241–2247Academic Press (2001).

Smith, J. A., Hillenbrand, C. D., Pudsey, C. J., Allen, C. S. & Graham, A. G. C. The presence of polynyas in the Weddell Sea during the Last Glacial Period with implications for the reconstruction of sea-ice limits and ice sheet history. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 296, 287–298 (2010).

Elderfield, H. & Ganssen, G. Past temperature and delta O-18 of surface ocean waters inferred from foraminiferal Mg/Ca ratios. Nature 405, 442–445 (2000).

Stumm, W. & Morgan, J. J. Aquatic Chemistry 2nd edn 477Wiley (1981).

Luther, G. W. et al. Simultaneous measurement of O-2, Mn, Fe, I-, and S(-II) in marine pore waters with a solid-state voltammetric microelectrode. Limnol. Oceonogr. 43, 325–333 (1998).

Hull, P. M., Osborn, K. J., Norris, R. D. & Robison, B. H. Seasonality and depth distribution of a mesopelagic foraminifer, Hastigerinella digitata, in Monterey Bay, California. Limnol. Oceonogr. 56, 562–576 (2011).

Kuepper, F. C. et al. Commemorating two centuries of iodine research: an interdisciplinary overview of current research. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 11598–11620 (2011).

Stramma, L., Huttl, S. & Schafstall, J. Water masses and currents in the upper tropical northeast Atlantic off northwest Africa. J Geophys. Res. Oceans 110, (2005).

Truesdale, V. W. & Bailey, G. W. Dissolved iodate and total iodine during an extreme hypoxic event in the Southern Benguela system. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 50, 751–760 (2000).

Farrenkopf, A. M. & Luther, G. W. Iodine chemistry reflects productivity and denitrification in the Arabian Sea: evidence for flux of dissolved species from sediments of western India into the OMZ. Deep Sea Res. II 49, 2303–2318 (2002).

Kohfeld, K. E., Anderson, R. F. & Lynch-Stieglitz, J. Carbon isotopic disequilibrium in polar planktonic foraminifera and its impact on modern and Last Glacial Maximum reconstructions. Paleoceanography 15, 53–64 (2000).

Talley, L. D. Closure of the global overturning circulation through the indian, pacific, and southern oceans: schematics and transports. Oceanography 26, 80–97 (2013).

McCave, I. N., Carter, L. & Hall, I. R. Glacial-interglacial changes in water mass structure and flow in the SW Pacific Ocean. Quart. Sci. Rev. 27, 1886–1908 (2008).

Ellwood, M. J., Wille, M. & Maher, W. Glacial Silicic Acid Concentrations in the Southern Ocean. Science 330, 1088–1091 (2010).

Chance, R., Baker, A. R., Carpenter, L. & Jickells, T. D. The distribution of iodide at the sea surface. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 16, 1841–1859 (2014).

Bluhm, K., Croot, P. L., Huhn, O., Rohardt, G. & Lochte, K. Distribution of iodide and iodate in the Atlantic sector of the southern ocean during austral summer. Deep Sea Res. II 58, 2733–2748 (2011).

Mackensen, A. Strong thermodynamic imprint on Recent bottom-water and epibenthic delta C-13 in the Weddell Sea revealed: Implications for glacial Southern Ocean ventilation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317, 20–26 (2012).

Luthi, D. et al. High-resolution carbon dioxide concentration record 650,000-800,000 years before present. Nature 453, 379–382 (2008).

Jaccard, S. L. et al. Two modes of change in southern ocean productivity over the past million years. Science 339, 1419–1423 (2013).

Moy, A. D., Howard, W. R. & Gagan, M. K. Late Quaternary palaeoceanography of the Circumpolar Deep Water from the South Tasman Rise. J. Quat. Sci. 21, 763–777 (2006).

Galbraith, E. D. & Jaccard, S. L. Deglacial weakening of the oceanic soft tissue pump: global constraints from sedimentary nitrogen isotopes and oxygenation proxies. Quart. Sci. Rev. 109, 38–48 (2015).

Jaccard, S. L., Galbraith, E. D., Martínez-García, A. & Anderson, R. F. Covariation of deep Southern Ocean oxygenation and atmospheric CO2 through the last ice age. Nature 530, 207–210 (2016).

Barker, S., Greaves, M. & Elderfield, H. A study of cleaning procedures used for foraminiferal Mg/Ca paleothermometry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4, (2003).

Comiso, J. C. Large-Scale Characteristics and Variability of the Global Sea Ice Cover 112–142Blackwell (2003).

Olbers, D., Gouretski, V., Seiss, G. & Schroeter, J. Hydrographic Atlas of the Southern Ocean Alfred-Wegener Institute (AWI) (1992).

Truesdale, V. W., Bale, A. J. & Woodward, E. M. S. The meridional distribution of dissolved iodine in near-surface waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Progress Oceonagr. 45, 387–400 (2000).

Campos, M., Farrenkopf, A. M., Jickells, T. D. & Luther, G. W. A comparison of dissolved iodine cycling at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-Series station and Hawaii Ocean Time-Series Station. Deep Sea Res. II 43, 455–466 (1996).

Wong, G. T. F. Dissolved iodine across the Gulf Stream Front and in the South Atlantic Bight. Deep Sea Res. I 42, 2005–2023 (1995).

Farrenkopf, A. M., Dollhopf, M. E., NiChadhain, S., Luther, G. W. & Nealson, K. H. Reduction of iodate in seawater during Arabian Sea shipboard incubations and in laboratory cultures of the marine bacterium Shewanella putrefaciens strain MR-4. Mar. Chem. 57, 347–354 (1997).

Smith, J. D., Butler, E. C. V., Airey, D. & Sandars, G. Chemical-properties of a low-oxygen water column in port-hacking (Australia) - arsenic, iodine and nutrients. Mar. Chem. 28, 353–364 (1990).

Emerson, S., Cranston, R. E. & Liss, P. S. Redox species in a reducing fjord - equilibrium and kinetic considerations. Deep Sea Res. A 26, 859–878 (1979).

Acknowledgements

Z.L. thanks NSF OCE 1232620. B.A.A.H. is supported by Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) grant NE/I020563/1. C.-D.H. is supported by NERC. Z.L. and R.E.M.R. were supported by NERC NE/E018432/1 during the initial development of the I/Ca proxy. We thank the captains, officers, crews and shipboard scientists of expeditions JR179 and ANT-XI/3 for recovering cores TC493 and PS2547, Professor David Hodell and Professor Andreas Mackensen for analysing stable isotopes on these cores, and Dr Hannes Grobe for providing samples from core PS2547. We acknowledge Professor Nick McCave for providing some of the core top materials and Mr Thomas Williams provided assistance for Fig. 1. This research used samples provided by the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP). ODP is sponsored by the US National Science Foundation and participating countries under management of the Joint Oceanographic Institutions (JOI). This manuscript greatly benefited from comments by Dr Nicolaas Glock and two anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., X.Z., K.M.G. and W.L. carried out the I/Ca analysis. C.-D.H. provided all samples from core TC493 and CaCO3 and stable isotope data for cores TC493 and PS2547. B.A.A.H. and L.J. contributed the core top samples. E.T. identified E. exigua. All authors participated in data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-2, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References. (PDF 734 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Z., Hoogakker, B., Hillenbrand, CD. et al. Oxygen depletion recorded in upper waters of the glacial Southern Ocean. Nat Commun 7, 11146 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11146

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11146

This article is cited by

-

Iodine content of fish otoliths in species found in diverse habitats

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2022)

-

Vertical decoupling in Late Ordovician anoxia due to reorganization of ocean circulation

Nature Geoscience (2021)

-

The Mesoproterozoic Oxygenation Event

Science China Earth Sciences (2021)

-

Response of a comprehensive climate model to a broad range of external forcings: relevance for deep ocean ventilation and the development of late Cenozoic ice ages

Climate Dynamics (2019)

-

Glacial expansion of oxygen-depleted seawater in the eastern tropical Pacific

Nature (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.