Abstract

Binary transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers share common properties such as a direct optical bandgap, spin-orbit splittings of hundreds of meV, light–matter interaction dominated by robust excitons and coupled spin-valley states. Here we demonstrate spin-orbit-engineering in Mo(1−x)WxSe2 alloy monolayers for optoelectronics and applications based on spin- and valley-control. We probe the impact of the tuning of the conduction band spin-orbit spin-splitting on the bright versus dark exciton population. For MoSe2 monolayers, the photoluminescence intensity decreases as a function of temperature by an order of magnitude (4–300 K), whereas for WSe2 we measure surprisingly an order of magnitude increase. The ternary material shows a trend between these two extreme behaviours. We also show a non-linear increase of the valley polarization as a function of tungsten concentration, where 40% tungsten incorporation is sufficient to achieve valley polarization as high as in binary WSe2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) monolayers are newly discovered semiconductors for a wide range of applications in electronics and optoelectronics1,2,3,4. In addition to detailed studies on binary monolayers5,6,7,8,9,10,11, recent work on alloy-based monolayers have allowed tuning the optical bandgap12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The current generation of commercial optoelectronic devices based on III–V semiconductors owes its success to alloy engineering, adapting the optical and electronic properties of epitaxial layers by tuning the band structure and band alignment of each layer22. TMDC alloys provide additional tuning possibilities as strong spin-orbit (SO) coupling splits the spin states in the valence band (hundreds of meV)3,23 and in the conduction band (up to few tens of meV)5,24,25. Because the SO-coupling depends mainly on the transition metal d-orbitals, the valence band spin-splitting for WSe2 (∼400 meV (ref. 23)) is roughly twice that of MoSe2 (∼200 meV (ref. 3)). This should allow for a wide-tuning range in ternary alloys13. However, integrating monolayer (ML) TMDCs in realistic photonic and optoelectronic devices demands efficient optical emission.

For high optical quality alloy materials, the first challenge during crystal growth is to avoid phase separation and defect/cluster formation. This is a particular concern for materials containing anion atoms with large electronegativity or lattice constant differences. Owing to the rather close electronegativity and lattice constant values, as well as high miscibility, TMDCs alloys are stable at room temperatures26. Previously, TMDCs alloys were synthesized either by mixing different chalcogen atoms (MX2(1−n)Y2n) or transition metals (M(1−x)ZxX2) for broadly tunable optical bandgaps. This was achieved using chemical vapour deposition or conventional low-pressure vapour transport (LPVT) techniques to yield materials in monolayer or bulk (layered) form13,18,19,14.

In the following, we experimentally demonstrate efficient optical emission in a wide-tuning range in Mo(1−x)WxSe2. Here the sign of the spin-splitting in the conduction band, which depends on the transition metal5,24,25, determines the nature of the A-exciton ground state as optically bright or dark (Fig. 1a), where electron-hole Coulomb exchange effects also play a role27. Our experiments demonstrate that the light emission efficiency can be tuned by alloying. The sign of the spin-splitting has also important consequences for spin and valley control. By studying monolayers of high quality (Mo, W)Se2 ternary alloys at various compositions, we tune the SO-induced spin splittings, which strongly impact the optically generated valley polarization and the bright versus dark exciton recombination.

(a) Simple band structure scheme in the K+ valley (at the K point of the Brillouin zone) to indicate the different signs and magnitudes of the valence  and conduction band spin splittings

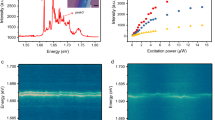

and conduction band spin splittings  when going from MoSe2 to WSe2 monolayers. Optically bright (red arrows) and dark (grey arrows) A-exciton transitions are indicated. (b) Nano-resolution x-ray photoelectron (nano-XPS) measurements on Mo(1−x)WxSe2 alloys showing gradual composition change with varying x, where orange, green, blue, red, black correspond to x=0%, 30%, 40%, 90 and 100%, respectively. For increasing x (W) content, W (Mo) content increases (decreases), whereas selenium ratio remains at the same values without any significant single or double (VSe and V2Se) vacancy formation. (c) E2g Raman peak position shift as a function of composition x. (d) Low temperature photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy is a very simple and efficient technique to probe the material quality. Impurities and defects will trap optically excited carriers, resulting in emission below the optical bandgap. PL spectrum at T=4 K of Mo0.7W0.3Se2 alloy monolayer showing very sharp emission of the charged exciton (trion T) and the neutral A-exciton (A) and negligible defect-related emission. Inset: representation of the alloy monolayer, the order of magnitude of the Bohr radius aB of an electron–hole pair (exciton) is shown. The narrow PL linewidth therefore indicates high quality alloy material on a nano-scopic scale. (e) PL spectra at 4 K of monolayers for tungsten (W) composition from x=0 to 100% in Mo(1−x)WxSe2. The dominant, sharp A-exciton emission is indicated.

when going from MoSe2 to WSe2 monolayers. Optically bright (red arrows) and dark (grey arrows) A-exciton transitions are indicated. (b) Nano-resolution x-ray photoelectron (nano-XPS) measurements on Mo(1−x)WxSe2 alloys showing gradual composition change with varying x, where orange, green, blue, red, black correspond to x=0%, 30%, 40%, 90 and 100%, respectively. For increasing x (W) content, W (Mo) content increases (decreases), whereas selenium ratio remains at the same values without any significant single or double (VSe and V2Se) vacancy formation. (c) E2g Raman peak position shift as a function of composition x. (d) Low temperature photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy is a very simple and efficient technique to probe the material quality. Impurities and defects will trap optically excited carriers, resulting in emission below the optical bandgap. PL spectrum at T=4 K of Mo0.7W0.3Se2 alloy monolayer showing very sharp emission of the charged exciton (trion T) and the neutral A-exciton (A) and negligible defect-related emission. Inset: representation of the alloy monolayer, the order of magnitude of the Bohr radius aB of an electron–hole pair (exciton) is shown. The narrow PL linewidth therefore indicates high quality alloy material on a nano-scopic scale. (e) PL spectra at 4 K of monolayers for tungsten (W) composition from x=0 to 100% in Mo(1−x)WxSe2. The dominant, sharp A-exciton emission is indicated.

Results

Preparation and characterization of highly crystalline samples

For this study Mo(1−x)WxSe2 monolayers were exfoliated from their bulk counterparts, which were grown using LPVT (see Methods). We confirm the intended stoichiometry values using nano-x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (nano-XPS), see Fig. 1b. Nano-XPS data taken from different spots closely match each other with 2% W/Mo deviation and implies that synthesized materials are uniform in composition. For different x values in Mo(1−x)WxSe2 monolayers, the most prominent in-plane Raman peak (E2g) gradually shifts from 241 to 251 cm−1 in Fig. 1c with slight deviation from linearity, which can be explained by the modified random element iso-displacement model12,19.

Photoluminescence (PL) results shown in Fig. 1d confirm the high quality of the ternary monolayers. Remarkably, in monolayer Mo0.7W0.3Se2, we detect virtually no defect-related emission. The PL is dominated by two sharp peaks, the neutral exciton A and the trion T, just as in the case of binary MoSe2 (refs 28, 29). The A-exciton PL full width at half maximum (FWHM) of only 9 meV is extremely narrow for a ternary alloy compared, for instance, with the typical PL FWHM of binary MoS2 of about 50 meV (ref. 4). The narrow PL linewidth allows us to determine the energy position of the A-exciton as a function of tungsten content in Fig. 1e. We observe band gap bowing as we deviate from a strictly linear extrapolation between the binary bandgaps12,13,15,16,17.

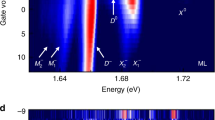

Determination of A- to B-exciton splitting

Having analysed the high quality and alloy composition of the samples, we now aim to determine how the SO-coupling can be tuned for optoelectronics and valley polarization control. Reflectivity gives access to both A- and B-exciton energies, whose separation, determined mainly by SO-coupling, is plotted in Fig. 2a. Reflectivity spectra are shown in Fig. 2c. Spectrally narrow transitions confirm the position of the A-exciton at the same energy as the PL measurements for x=0.3 and x=0.9, indicating that exciton localization (Stokes shift) on defects, for example, is negligible. The transition several hundred meV above the A-exciton is due to the B-exciton that clearly shifts as the tungsten content is increased. We also perform PL excitation spectroscopy to access further details: When the laser is in resonance with the B-exciton, we observe a strong enhancement of the A-exciton PL emission intensity, as can be clearly seen for monolayer Mo0.7W0.3Se2 in Fig. 2b for a laser energy of 1.98 eV. We have performed experiments identical to Fig. 2b for all investigated samples using 30 different laser energies. The results are presented in Fig. 2d using the A-exciton as the detection energy. We clearly see a shift in energy of the maxima associated to the B-exciton as the tungsten content is varied, in agreement with our reflectivity results. Over the x=30–40% range, major changes of the exciton energies and SO splittings can be seen in our measurements. As a consequence, minor alloy fluctuations could lead to a spread in transition energies in this critical alloy composition range as for x=40% in Fig. 1e. This is not observed to this extent for other composition ranges.

(a) The splitting between A- and B-excitons is measured by PL excitation spectroscopy (PLE) (red squares), where error bars correspond to laser energy step size and reflectivity (open circles), with error bars from multi-Lorentzian fits. The sum of the valence band and conduction band spin splittings calculated by DFT is shown for comparison, for individual values and computational details see Methods and Supplementary Note 1. (b) PL spectra of A-exciton in monolayer Mo0.7W0.3Se2 for different laser excitation energies. We uncover a clear maximum when the laser energy is in resonance with the B-exciton. (c) Reflectivity spectra using a white light source, uncovering in addition to the A-exciton also the B-exciton spectral position that can be tuned by varying the alloy composition. Dotted lines are a guide to the eye to indicate the energy shifts. (d) Same measurements as b but for all samples, the A-exciton PL intensity is plotted as a function of laser energy. These PLE measurements allow determining the B-exciton energy with very high precision.

The values of the A–B exciton splitting measured with two independent techniques are summarized in Fig. 2a. The valence band SO-splitting can be measured directly by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), for example, refs 3, 23. In optical spectroscopy, the energy position of the exciton transitions will in addition depend on the difference between A- and B-exciton-binding energies (expected to be small following measurements of similar values for 1s to 2s/2p separation for A- and B-excitons8,30) and the SO-splitting in the conduction band (up to tens of meV (refs 24, 25)). For Mo0.7W0.3Se2 monolayers, we measure an A–B exciton separation of 320 meV, an increase of 50% compared with binary MoSe2. For Mo0.6W0.4Se2, the separation is about 420 meV, very close to the value of 425 meV we measure for binary WSe2. Surprisingly, our experiments show a clear SO bowing, which has not been anticipated yet by theory as SO effects where not included in refs 15, 16, 17. Spin-orbit bowing has been observed in other systems such as III–V semiconductor alloys31. For order of magnitude estimations, we have calculated valence and conduction band splittings by density functional theory using an artificial supercell with just four transition metal atoms in ordered configurations, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 with details in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table 1. We show the sum of valence and conduction band splittings for comparison with the experiments in Fig. 2a, the influence of the realistic local lattice symmetry15,16,17,31, possibly different A- and B-exciton-binding energies and effective masses is not included5.

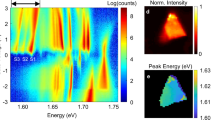

Investigating order of dark and bright exciton states

We have quantified the evolution of A–B exciton separation, mainly due to SO-coupling. Our next target is to show how tuning the amplitude and for the conduction band possibly the sign of the SO-coupling can be used to engineer the optoelectronic and spin-valley properties. Increasing the light emission efficiency is one of the main challenges for successful integration of TMDC MLs in realistic photonic and optoelectronic devices. This challenge can be tackled by SO-engineering in alloys, as the sign and amplitude of the SO-splitting in the conduction band will strongly influence the balance between optically dark and bright transitions in WSe2, MoSe2 and ternary alloys (see energy level diagram in Fig. 1a). This has a direct impact on the light emission yield from cryogenic to room temperatures, the SO-coupling therefore needs to be controlled for optoelectronics applications. Our set-up sketched in Fig. 3a allows for a quantitative comparison between samples. We are able to uncover important differences between WSe2, MoSe2 and the ternary samples, as can be seen directly when comparing the PL intensities in Fig. 3b. For monolayer WSe2, we detect comparatively weak emission at 4 K, increasing by 1 order of magnitude when going to T=300 K (Fig. 3c), a trend also observed in ref. 32. One possible explanation for the increase of the PL intensity as a function temperature is the thermal conversion of dark into bright states, as observed for CdSe nano-crystals33, where dark states also lie energetically below bright states. In stark contrast, for binary MoSe2 monolayers, we find a drastic decrease of the PL emission intensity when going from T=4 to 150 K, consistent with the opposite order of bright and dark states compared with WSe2, see Fig. 1a. The ternary sample Mo0.3W0.7Se2 shows a behaviour qualitatively similar to binary MoSe2, albeit with much stronger emission for temperatures from 100 to 200 K. For temperatures between 4 and 100 K, we are able to extract separately the PL intensity evolution of the trion and the neutral A-exciton for binary and ternary samples, see Supplementary Fig. 2 for full details. For binary MoSe2, we find that the trion intensity decreases much faster with temperature than the neutral exciton one. In contrast, for monolayer Mo0.3W0.7Se2 the trion and A-exciton PL intensity show similar temperature dependence. For a fully quantitative analysis of the global PL yield evolution, non-radiative channels due to material imperfections need to be taken into account in addition to the dark-bright state competition discussed here. We have confirmed the stark contrast between MoSe2 and WSe2 for monolayers not only from our LPVT samples but also from commercial material, which shows the same behaviour (see Supplementary Fig. 3). These temperature-dependent PL measurements provide a first experimental indication of the sign of the conduction band SO-splitting in these promising materials for optoelectronics. A detailed analysis of the potential impact of the bright versus dark exciton recombination in MoSe2 and WSe2 monolayers can be found in the very recent theory of ref. 34. For a more direct measurement of the conduction band spin splittings, ARPES experiments with sufficient energy resolution (meV range) would be desirable in future experiments.

(a) Comparing the global PL emission intensity of several samples is challenging, as the set-up has to compensate thermal expansion/movement. For the measurements of the PL emission intensity as a function of temperature, we have exfoliated several monolayer flakes of different materials in close proximity onto the same substrate, which is mounted on a three-axis attocube nano-positioner. Therefore PL emission for different samples are measured under identical conditions, that is, same detection and laser spot size. Only highly reproducible in-plane movement is needed to change sample. (b) The PL spectra of monolayer MoSe2, Mo0.3W0.7Se2 and WSe2 are shown for different temperatures, the relative intensities can be directly compared. (c) Using the spectra from b, we integrate the total number of counts including A-exciton and trion (MoSe2 and Mo0.3W0.7Se2) and in addition the localized states (WSe2). We compare the total number of counts for the three monolayer materials as a function of temperature, see Supplementary Note 2 for details (d) The measured valley polarization, that is, circular PL polarization degree Pc is plotted as a function of tungsten (W) content in the sample. Pc is defined as  , where I+ and I− are the σ+ and σ− polarized PL components, respectively. We observe a highly non-linear increase in the valley polarization as more tungsten is incorporated. For the measurement, for each sample the laser energy is 140 meV above the A-exciton. The error bars correspond to the polarization resolution of our set-up. (e) Using σ+ circularly polarized laser excitation, we detect the A-exciton emission in σ+ (black) and σ− (red) polarization. For x=0.3, we detect no polarization, as for binary MoSe2. Surprisingly, for x=0.4 we detect up to 40% PL polarization. The results for x=0.9 also show high polarization. (f) The circular PL polarization Pc is plotted as a function of the excitation laser energy to find optimal valley polarization conditions. While for x≤0.3 the valley polarization remains low, we demonstrate for x⩾0.4 a wide range of laser excitation energies that can be used for valley index initialization.

, where I+ and I− are the σ+ and σ− polarized PL components, respectively. We observe a highly non-linear increase in the valley polarization as more tungsten is incorporated. For the measurement, for each sample the laser energy is 140 meV above the A-exciton. The error bars correspond to the polarization resolution of our set-up. (e) Using σ+ circularly polarized laser excitation, we detect the A-exciton emission in σ+ (black) and σ− (red) polarization. For x=0.3, we detect no polarization, as for binary MoSe2. Surprisingly, for x=0.4 we detect up to 40% PL polarization. The results for x=0.9 also show high polarization. (f) The circular PL polarization Pc is plotted as a function of the excitation laser energy to find optimal valley polarization conditions. While for x≤0.3 the valley polarization remains low, we demonstrate for x⩾0.4 a wide range of laser excitation energies that can be used for valley index initialization.

Probing optical valley initialization

We also investigate the impact of tuning the sign and amplitude of the SO-coupling on spin and valley physics in TMDC monolayers. The electron valley degree-of-freedom is accessible in monolayer TMDCs in simple optical manipulation schemes2,10,11 and is coupled to the electron spin degree-of-freedom. For this reason valleytronics is one of the main research directions in TMDCs2,9. Energetically degenerate states in the K+ and K− valleys have opposite spins due to time reversal symmetry2,10. Large SO splittings will also stabilize the valley index, as spin flips are necessary to change valley in momentum space. Although MoSe2 and WSe2 show comparable structural and optical quality28,35,36, their valley polarization properties are very different: in WSe2 not only valley polarization can be generated, but also a superposition of K+ and K− states, termed exciton valley coherence35. In contrast, the valley polarization of MoSe2 at zero magnetic field rarely exceeds 5% using various optical initialization schemes29,36. Here we investigate how valley polarization generation improves in TMDC alloys as we go from MoSe2 to WSe2, see Fig. 3d. For the high quality x=0.3 sample, we do not detect measurable valley polarization when scanning a very broad range of laser energies, as can be seen in Fig. 3e,f. By increasing the tungsten content by only 10% to x=0.4 we can increase the valley polarization by an order of magnitude to about 40%. An efficient way for successful optical valley initialization of the A-exciton is to tune the excitation laser into resonance with exciton ground or excited states8. For MoSe2, the B-exciton 1s and the A-exciton 2s/2p states overlap energetically30, which might be one of the reasons that prevents optical valley initialization. The specific band structure of ML MoSe2 could also play a role30. For WSe2, the situation is much simpler, as the B-excion is at much higher energy compared with the excited A-exciton states. For x=0.4, we are again in this favourable situation, which might be beneficial for optical valley initialization.

In summary, we demonstrate SO engineering in Mo(1−x)WxSe2 alloy monolayers for optoelectronics and applications based on electron spin- and valley-control. We show a non-linear increase of the optically generated valley polarization as a function of tungsten concentration, where 40% tungsten incorporation is sufficient to achieve valley polarization as high as in binary WSe2. We also probe the impact of the tuning of the conduction band SO spin-splitting on the bright versus dark exciton population, that is, PL emission intensity. We show that the MoSe2 PL intensity decreases as a function of temperature by an order of magnitude, whereas for WSe2 we measure surprisingly an order of magnitude increase over the same temperature range (T=4–300 K). The ternary material shows a trend between these two extreme behaviours. These results demonstrate that alloying is a promising technique for optimizing the light emission efficiency and valley index stability in two-dimensional TMDCs.

Methods

Sample growth and characterization

Layered Mo(1−x)WxSe2 semiconductors were grown by modified LPVT technique to achieve high optical quality materials. Synthesized materials are fully alloyed (not phase separated) as confirmed by three complementary techniques, such as sub-micron Raman spectroscopy, sub-micron PL and nano-XPS, see Fig. 1. X-ray diffraction measurements display sharp (∼1-μm domain size) (001) peaks. Thus TMDCs alloys are highly layered and crystallized in the hexagonal phase, and contains negligible amount of minority crystal orientation. Observed (001) peaks of Mo(1−x)WxSe2 appear at the same position (within <0.08°) implying that alloys have similar c-axis parameters. Consistent with nano-XPS measurements, Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy data collected from ∼100-μm diameter circle agrees well with the XPS measurements (not shown).

Optical spectroscopy

Experiments at T=4–300 K are carried out in a confocal microscope8. The detection spot diameter is ≈1 μm, that is, considerably smaller than the monolayer flake size of ∼10 × 10 μm2. For time integrated experiments, the PL emission is dispersed in a spectrometer and detected with a Si-CCD camera. The samples are excited either by a continuous wave (cw) He–Ne laser or pico-second (ps) pulses generated by a tunable frequency-doubled optical parametric oscillator synchronously pumped by a mode-locked Ti:Sa laser. The typical pulse temporal and spectral widths are 1.6 ps and 3 meV, respectively, the repetition rate is 80 MHz.

Theory

The electronic structures of Mo(1−x)WxSe2 with x=0.25,0.50,0.75 were simulated within the DFT framework as implemented in the VASP37 package. The conduction and valence spin-splitting of these elemental compositions were simply computed in a (2 × 2) supercell, containing four transition metal atoms in total and neglecting for simplicity random and more realistic configurations, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wang, G. et al. Spin-orbit engineering in transition metal dichalcogenide alloy monolayers. Nat. Commun. 6:10110 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10110 (2015).

References

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer mos2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497501 (2013).

Xu, X., Xiao, D., Heinz, T. F. & Yao, W. Spin and pseudospins in layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 10, 343–350 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Direct observation of the transition from indirect to direct bandgap in atomically thin epitaxial mose2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 111–115 (2014).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin mos2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Kormanyos, A. et al. k.p theory for two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. 2D Mater. 2, 022001 (2015).

Ye, Z. et al. Probing excitonic dark states in single-layer tungsten disulfide. Nature 513, 214–218 (2014).

Ugeda, M. M. et al. Observation of giant bandgap renormalization and excitonic effects in a monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 13, 1091–1095 (2014).

Wang, G. et al. Giant enhancement of the optical second-harmonic emission of wse2 monolayers by laser excitation at exciton resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 097403 (2015).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley hall effect in mos2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Cao, T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism in mos2 . Nat. Commun. 3, 887 (2012).

Sallen, G. et al. Robust optical emission polarization in mos2 monolayers through selective valley excitation. Phys. Rev. B 86, 081301 (2012).

Tongay, S. et al. Two-dimensional semiconductor alloys: Monolayer mo1xwxse2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 012101 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Tunable band gap photoluminescence from atomically thin transition-metal dichalcogenide alloys. ACS Nano 7, 4610–4616 (2013).

Zheng, S. et al. Monolayers of wxmo1xs2 alloy heterostructure with in-plane composition variations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 063113 (2015).

Kutana, A., Penev, E. S. & Yakobson, B. I. Engineering electronic properties of layered transition-metal dichalcogenide compounds through alloying. Nanoscale 6, 5820–5825 (2014).

Gan, L.-Y., Zhang, Q., Zhao, Y.-J., Cheng, Y. & Schwingenschlögl, U. Order-disorder phase transitions in the two-dimensional semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenide alloys Mo1−xWxX2 (X=S, Se, and Te). Sci. Rep. 4, 6691–6695 (2014).

Xi, J., Zhao, T., Wang, D. & Shuai, Z. Tunable electronic properties of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide alloys: a first-principles prediction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 285–291 (2014).

Feng, Q. et al. Growth of large-area 2d mos2(1-x)se2x semiconductor alloys. Adv. Mater. 26, 2648–2653 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Composition-dependent raman modes of mo1-xwxs2 monolayer alloys. Nanoscale 6, 2833–2839 (2014).

Zhang, M. et al. Two-dimensional molybdenum tungsten diselenide alloys: Photoluminescence, raman scattering, and electrical transport. ACS Nano 8, 7130–7137 (2014).

Su, S.-H. et al. Band gap-tunable molybdenum sulfide selenide monolayer alloy. Small 10, 2589–2594 (2014).

Rosencher, E. & Vinter, B. Optoelectronics Cambridge Univ. Press (2002).

Riley, J. et al. Direct observation of spin-polarized bulk bands in an inversion-symmetric semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 835–839 (2014).

Liu, G.-B., Shan, W.-Y., Yao, Y., Yao, W. & Xiao, D. Three-band tight-binding model for monolayers of group-vib transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085433 (2013).

Kosmider, K., González, J. W. & Fernández-Rossier, J. Large spin splitting in the conduction band of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 88, 245436 (2013).

Kang, J., Tongay, S., Li, J. & Wu, J. Monolayer semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenide alloys: Stability and band bowing. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 143703 (2013).

Qiu, D. Y., Cao, T. & Louie, S. G. Nonanalyticity, valley quantum phases, and lightlike exciton dispersion in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides: Theory and first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 176801 (2015).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrical control of neutral and charged excitons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 4, 1474 (2013).

Wang, G. et al. Polarization and time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy of excitons in mose2 monolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 112101 (2015).

Wang, G. et al. Exciton states in monolayer MoSe2: impact on interband transitions. 2D Mater 2, 045005 (2015).

Wei, S.-H. & Zunger, A. Band gaps and spin-orbit splitting of ordered and disordered alxga1−xAs and Gaasxsb1−x alloys. Phys. Rev. B 39, 3279–3304 (1989).

Arora, A. et al. Excitonic resonances in thin films of WSe2: From monolayer to bulk material. Nanoscale 7, 10421–10429 (2015).

Crooker, S. A., Barrick, T., Hollingsworth, J. A. & Klimov, V. I. Multiple temperature regimes of radiative decay in cdse nanocrystal quantum dots: Intrinsic limits to the dark-exciton lifetime. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 2793–2795 (2003).

Dery, H. & Song, Y. Polarization analysis of excitons in monolayer and bilayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 92, 125431 (2015).

Jones, A. M. et al. Optical generation of excitonic valley coherence in monolayer wse2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 634–638 (2013).

MacNeill, D. et al. Breaking of valley degeneracy by magnetic field in monolayer mose2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 037401 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from ERC Grant No. 306719, ANR MoS2ValleyControl. I.C.G. acknowledges the CNRS for financial support and CALMIP initiative for the generous allocation of computational times, through the project p0812, as well as the GENCI-CINES and GENCI-IDRIS for the grant x2015096649. S.T. acknowledges Arizona State University start-up grant and Ira. A. Fulton College of Engineering Origami Seeding Funds. X.M. acknowledges support of Institut Universitaire de France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S., B.C., S.A. and S.Y. synthesized the samples. S.T. designed characterization and synthesis measurements. I.C.G. performed DFT calculations; B.U. and X.M. conceived optical spectroscopy experiments; G.W. and C.R. performed optical spectroscopy; G.W. and T.A. analysed the data; B.U., G.W. and C.R. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary References (PDF 4421 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Robert, C., Suslu, A. et al. Spin-orbit engineering in transition metal dichalcogenide alloy monolayers. Nat Commun 6, 10110 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10110

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10110

This article is cited by

-

Exciton spectroscopy and unidirectional transport in MoSe2-WSe2 lateral heterostructures encapsulated in hexagonal boron nitride

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)

-

Brightening of a dark monolayer semiconductor via strong light-matter coupling in a cavity

Nature Communications (2022)

-

The optical response of artificially twisted MoS\(_2\) bilayers

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Bosonic condensation of exciton–polaritons in an atomically thin crystal

Nature Materials (2021)

-

Nanoscale redox mapping at the MoS2-liquid interface

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.