Abstract

Quantum technologies promise a variety of exciting applications. Even though impressive progress has been achieved recently, a major bottleneck currently is the lack of practical certification techniques. The challenge consists of ensuring that classically intractable quantum devices perform as expected. Here we present an experimentally friendly and reliable certification tool for photonic quantum technologies: an efficient certification test for experimental preparations of multimode pure Gaussian states, pure non-Gaussian states generated by linear-optical circuits with Fock-basis states of constant boson number as inputs, and pure states generated from the latter class by post-selecting with Fock-basis measurements on ancillary modes. Only classical computing capabilities and homodyne or hetorodyne detection are required. Minimal assumptions are made on the noise or experimental capabilities of the preparation. The method constitutes a step forward in many-body quantum certification, which is ultimately about testing quantum mechanics at large scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many-body quantum devices promise exciting applications in ultraprecise quantum metrology1, quantum computing2,3,4 and quantum simulators5,6,7,8,9. In the quest for their large-scale realization, impressive progress on a variety of quantum technologies has recently been made6,7,8,9. Among these technologies, optical platforms play a key role. For example, sophisticated manipulations of multi-qubit entangled states of up to eight parametrically downconverted photons10,11 have been demonstrated and continuous-variable entanglement among 60 stable12 and up to 10,000 flying13 modes has been verified in optical set-ups. In addition, small-sized simulations of BosonSampling14,15,16,17 and Anderson localization in quantum walks18,19 have been performed with on-chip integrated linear-optical networks.

This fast pace of advance, however, makes the problem of reliable certification an increasingly pressing issue20,21,22,23,24. From a practical viewpoint, further experimental progress on many-body quantum technologies is nowadays hindered by the lack of practical certification tools. At a fundamental level, certifying many-body quantum devices is ultimately about testing quantum mechanics in regimes where it has never been tested before.

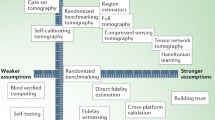

Tomographic characterization of quantum states requires the measurement of exponentially many observables. Compressed-sensing techniques25 reduce, for states approximated by low-rank density matrices, the requirements significantly, but still demand exponentially many measurements. Efficient certification techniques, requiring only polynomially many measurements, for universal quantum computation26,27,28 and a restricted model of computation with one pure qubit29 exist in the form of quantum interactive proofs. However, these require either a fully fledged fault-tolerant universal quantum computer26,27,28 or an experimentally non-trivial measurement-based quantum device29. In addition, these methods involve sequential interaction rounds with the device26,27,28,29. In contrast, permutationally invariant tomography30, tensor network techniques31, Monte Carlo fidelity estimation32,33,34, and Clifford-circuit benchmarking techniques35 provide experimentally friendly alternatives for the efficient certification of preparations of permutationally invariant30 and qubit stabilizer or W states32,33,34,35, respectively. Nevertheless, none of these methods addresses continuous-variable systems, not even in Gaussian states.

Here we introduce an experimentally friendly technique for the certification of continuous-variable state preparations without estimating the prepared state itself. First, we discuss intuitively and define precisely reliable quantum-state certification tests. We do this for two notions of certification, differing in that in one of them robustness against small preparation errors is mandatory. Then, we present a certification test, based on single-mode homodyne and heterodyne detection, for arbitrary m-mode pure Gaussian states, pure non-Gaussian states resulting from passive Gaussian unitary operations on Fock-basis states with n photons, and pure states prepared by post-selecting states in the latter class with Fock-basis measurements on a<m ancillary modes. This covers, for instance, Gaussian quantum simulations such as those of refs 12, 13 as well as the non-Gaussian ones of refs. 6, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. Furthermore, both photon-added or -subtracted linear-optical network states36,37,38,39 as well as all non-Gaussian states accessible to qumode-encoded qubit40,41 quantum computers also lie within the range of applicability of our method. For all Gaussian states and all mentioned non-Gaussian states with constant n, the protocol is efficient in m and, for the cases with post-selection, also in the inverse post-selection success probability.

With high probability, our test rejects all experimental preparations with a fidelity with respect to the chosen target state lower than a desired threshold and accepts if the preparation is sufficiently close to the target. That is, the protocol is robust against small preparation errors. We upper-bound the failure probability in terms of the number of experimental runs and calculate the necessary number of measurement settings. Our method is built on a fidelity lower bound, based on a natural extremality property, that is interesting in its own right. Finally, the experimental estimation of this bound relies on non-Gaussian state nullifiers, which we introduce on the way.

Results

Certification notions

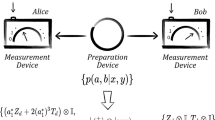

We present our results in terms of photons propagating through optical networks, but our methods apply to any bosonic platform with equivalent dynamics. We consider a sceptic certifier, Arthur, with limited quantum capabilities, who wishes to ascertain whether an untrusted quantum prover, Merlin, presumably with more quantum capabilities, can indeed prepare certain quantum states that Arthur cannot. This mindset is reminiscent to that of quantum interactive-proof systems26,27,28,29 of computer science, but our method has the advantage that no interaction apart from the measurements of the certifier on the single-run experimental preparations from the prover is required.

In particular, we consider the situation where Merlin possesses at least a network of active single-mode squeezers and displacers as well as passive beam-splitters and phase-shifters, sufficient to efficiently implement any m-mode Gaussian unitary42,43,44,45,46, plus single-photon sources. Arthur’s resources, in contrast, are restricted to classical computational power augmented with single-mode measurements. With that, he can characterize each of his single-mode measurement channels up to any desired constant precision. The task is for Merlin to provide Arthur with copies of an m-mode pure target state  of Arthur’s choice. We assume that Merlin follows independent and identical state-preparation procedures on each experimental run, described by the density matrix

of Arthur’s choice. We assume that Merlin follows independent and identical state-preparation procedures on each experimental run, described by the density matrix  . We refer to

. We refer to  as a preparation of the target state

as a preparation of the target state  . His preparation is unavoidably subject to imperfections and he might even be dishonest and try to trick Arthur. Thus, Arthur would like to run a test, with his own measurement devices, to certify whether

. His preparation is unavoidably subject to imperfections and he might even be dishonest and try to trick Arthur. Thus, Arthur would like to run a test, with his own measurement devices, to certify whether  is indeed a bona fide preparation of

is indeed a bona fide preparation of  .

.

To measure how good a preparation  of

of  is, we use the fidelity between

is, we use the fidelity between  and

and  , which we define as

, which we define as

where the last equality holds because  is assumed to be pure. Another usual definition of the fidelity corresponds to the square root of the fidelity as defined above. All our results can be adapted to that definition and also to the trace distance D:=D(

is assumed to be pure. Another usual definition of the fidelity corresponds to the square root of the fidelity as defined above. All our results can be adapted to that definition and also to the trace distance D:=D( ,

,  ), which can be defined via the 1-norm distance in state space as D(

), which can be defined via the 1-norm distance in state space as D( ,

, ):=Tr[|

):=Tr[| −

− |]/2. Note that D can be bounded from both sides in terms of F, as defined in equation (1), through the well-known inequalities

|]/2. Note that D can be bounded from both sides in terms of F, as defined in equation (1), through the well-known inequalities  , where the first inequality holds because

, where the first inequality holds because  is pure.

is pure.

Let us first discuss what properties an experimental test must fulfil to qualify as a state certification protocol. Different certification paradigms are schematically represented in Fig. 1. We start with the formal definition of certification in the sense of Fig. 1c.

(a) Naive approach: To certify an untrusted experimental preparation  of the target state

of the target state  , a certifier Arthur would like to run a statistical test that, for all

, a certifier Arthur would like to run a statistical test that, for all  , decides whether the fidelity F between

, decides whether the fidelity F between  and

and  is greater or equal than a prespecified threshold FT<1 (inner green region, accept), or smaller than it (outer red region, reject). However, due to the preparations at the boundary of the two regions and experimental uncertainties, a test able to make such a decision does not exist. (b) The ideal scenario: A more realistic certification notion is to ask that the test rejects every

is greater or equal than a prespecified threshold FT<1 (inner green region, accept), or smaller than it (outer red region, reject). However, due to the preparations at the boundary of the two regions and experimental uncertainties, a test able to make such a decision does not exist. (b) The ideal scenario: A more realistic certification notion is to ask that the test rejects every  for which F<FT (outer red region) and accepts every

for which F<FT (outer red region) and accepts every  for which F⩾FT+Δ (inner green region), for some given Δ<1−FT. Here a buffer region of width Δ (in grey) is introduced within which the behaviour of the test can be arbitrary, but, in return, the certification is now feasible. This type of certification is thus robust against experimental infidelities as large as 1−FT−Δ. (c) The practical scenario: Finally, the least one can demand is that the test rejects every

for which F⩾FT+Δ (inner green region), for some given Δ<1−FT. Here a buffer region of width Δ (in grey) is introduced within which the behaviour of the test can be arbitrary, but, in return, the certification is now feasible. This type of certification is thus robust against experimental infidelities as large as 1−FT−Δ. (c) The practical scenario: Finally, the least one can demand is that the test rejects every  for which F<FT (outer red region) and accepts at least

for which F<FT (outer red region) and accepts at least  (green point). The former condition is sometimes called soundness and the latter one completeness. Here no acceptance is guaranteed for any

(green point). The former condition is sometimes called soundness and the latter one completeness. Here no acceptance is guaranteed for any  with F⩾FT (grey region) other than

with F⩾FT (grey region) other than  itself, but any

itself, but any  accepted by the test necessarily features F⩾FT. This certification notion is not necessarily robust against state deviations, but it can be more practical. In addition, in practice, the resulting tests succeed also in accepting many

accepted by the test necessarily features F⩾FT. This certification notion is not necessarily robust against state deviations, but it can be more practical. In addition, in practice, the resulting tests succeed also in accepting many

for which F⩾FT.

for which F⩾FT.

Definition 1 (Quantum-state certification). Let  be a target state, FT<1 a threshold fidelity, and α>0 a maximal failure probability. A test, which takes as input copies of a preparation

be a target state, FT<1 a threshold fidelity, and α>0 a maximal failure probability. A test, which takes as input copies of a preparation  and outputs ‘accept’ or ‘reject’, is a certification test for

and outputs ‘accept’ or ‘reject’, is a certification test for  if, with probability at least 1−α, it both rejects every

if, with probability at least 1−α, it both rejects every  for which F(

for which F( ,

, ) <FT and accepts if

) <FT and accepts if  =

= . We say that any

. We say that any  accepted by such a test is a certified preparation of

accepted by such a test is a certified preparation of  .

.

Classes of target states

To specify the target states we need to introduce some notation. We denote m-mode Fock basis states by  , with n:=(n1, n2,…,nm) being the sequence of photon numbers nj⩾0 in each mode j∈[m], where the short-hand notation [m]:={1, 2,…,m} is introduced, and call

, with n:=(n1, n2,…,nm) being the sequence of photon numbers nj⩾0 in each mode j∈[m], where the short-hand notation [m]:={1, 2,…,m} is introduced, and call  the total input photon number. In particular, we will pay special attention to Fock basis states

the total input photon number. In particular, we will pay special attention to Fock basis states  with exactly one photon in each of the first n modes and the vacuum in the remaining m−n ones, that is, those for which n=1n, with

with exactly one photon in each of the first n modes and the vacuum in the remaining m−n ones, that is, those for which n=1n, with

Note that  is the Gaussian vacuum state

is the Gaussian vacuum state  . We denote the photon number operator corresponding to mode j by

. We denote the photon number operator corresponding to mode j by  and the total photon number operator by

and the total photon number operator by  .

.

In addition, for post-selected target states, we denote by  , where each element

, where each element  labels a different mode, the subset of

labels a different mode, the subset of  modes on which the post-selection measurements are made. We then identify the remaining m−a modes as the system subset

modes on which the post-selection measurements are made. We then identify the remaining m−a modes as the system subset  , which carries the post-selected target state

, which carries the post-selected target state  . The subindex

. The subindex  emphasizes that

emphasizes that  represents an (m−a)-mode post-selected target state and distinguishes it from m-mode target states without post-selection, which we denote simply as

represents an (m−a)-mode post-selected target state and distinguishes it from m-mode target states without post-selection, which we denote simply as  . We denote by

. We denote by  , with

, with  , an a-mode pure normalized Fock-basis state of

, an a-mode pure normalized Fock-basis state of  total photons on the modes

total photons on the modes  . We use the short-hand notations

. We use the short-hand notations  , where

, where  indicates partial trace over the Fock space of

indicates partial trace over the Fock space of  ,

,  denotes the identity on

denotes the identity on  , and

, and  is the post-selection success probability, that is, the probability of measuring

is the post-selection success probability, that is, the probability of measuring  in a projective measurement on

in a projective measurement on  . Without loss of generality, we consider throughout only the non-trivial case

. Without loss of generality, we consider throughout only the non-trivial case  .

.

With the notation introduced, we derive our results for: arbitrary m-mode pure Gaussian states, given by the class

m-mode pure linear-optical network states from the class

and (m−a)-mode pure locally post-selected linear-optical network states from the class

The three classes of target states are schematically represented in Fig. 2. The class  is crucial within the realm of ‘continuous-variable’ quantum optics and quantum information processing. It encompasses, for instance, ‘twin-beam’ (two-mode squeezed vacuum) states under passive networks, which are used to simulate, upon coincidence detection, multi-qubit states6. The class

is crucial within the realm of ‘continuous-variable’ quantum optics and quantum information processing. It encompasses, for instance, ‘twin-beam’ (two-mode squeezed vacuum) states under passive networks, which are used to simulate, upon coincidence detection, multi-qubit states6. The class  includes all the settings sometimes referred to as ‘discrete variable’ linear-optical networks. This class covers, among others, the targets of several recent experimental simulations with on-chip integrated linear-optical networks14,15,16,17,18,19. The third class,

includes all the settings sometimes referred to as ‘discrete variable’ linear-optical networks. This class covers, among others, the targets of several recent experimental simulations with on-chip integrated linear-optical networks14,15,16,17,18,19. The third class,  , is the one of linear-optical network states locally post-selected with Fock-basis measurements. This class includes important non-Gaussian resources for quantum information and quantum optics. For instance, it encompasses both photon-added or -subtracted linear-optical network states36,37,38,39. Furthermore, when n is proportional to m, it also includes all the states prepared by probabilistic schemes of the type of refs 40, 41 for universal qumode-encoded qubit quantum computation.

, is the one of linear-optical network states locally post-selected with Fock-basis measurements. This class includes important non-Gaussian resources for quantum information and quantum optics. For instance, it encompasses both photon-added or -subtracted linear-optical network states36,37,38,39. Furthermore, when n is proportional to m, it also includes all the states prepared by probabilistic schemes of the type of refs 40, 41 for universal qumode-encoded qubit quantum computation.

(a)  is the class composed of all m-mode pure Gaussian states. These can be prepared by applying an arbitrary Gaussian unitary Û (possibly involving multimode squeezing) to the m-mode vacuum state

is the class composed of all m-mode pure Gaussian states. These can be prepared by applying an arbitrary Gaussian unitary Û (possibly involving multimode squeezing) to the m-mode vacuum state  . (b) The class

. (b) The class  includes all m-mode pure non-Gaussian states produced at the output of an arbitrary linear-optical network, which implements a passive Gaussian unitary Û (without squeezing), with the Fock-basis state

includes all m-mode pure non-Gaussian states produced at the output of an arbitrary linear-optical network, which implements a passive Gaussian unitary Û (without squeezing), with the Fock-basis state  containing one photon in each of the first n modes and zero in the remaining m−n ones as input. As the order of the modes is arbitrary, choosing the first n modes as the populated ones does not constitute a restriction. (c) The third class,

containing one photon in each of the first n modes and zero in the remaining m−n ones as input. As the order of the modes is arbitrary, choosing the first n modes as the populated ones does not constitute a restriction. (c) The third class,  encompasses all (m−a)-mode pure non-Gaussian states obtained by projecting a subset

encompasses all (m−a)-mode pure non-Gaussian states obtained by projecting a subset  of a<m modes of an m-mode pure linear-optical network state

of a<m modes of an m-mode pure linear-optical network state  onto a pure normalized product Fock-basis state

onto a pure normalized product Fock-basis state  . In practice, this is done probabilistically by measuring

. In practice, this is done probabilistically by measuring  in a local basis that contains

in a local basis that contains  and post-selecting only the events in which

and post-selecting only the events in which  is measured. Thus, the a modes in

is measured. Thus, the a modes in  are used as ancillas, whereas the effective system is given by the subset

are used as ancillas, whereas the effective system is given by the subset  containing the other m−a modes, which carries the final target state. For concreteness, but without any loss of generality, in the plot, the ancillary modes are chosen to be the last a ones. These three classes cover the target states considered in the vast majority of quantum photonic experiments.

containing the other m−a modes, which carries the final target state. For concreteness, but without any loss of generality, in the plot, the ancillary modes are chosen to be the last a ones. These three classes cover the target states considered in the vast majority of quantum photonic experiments.

The certification test

The basis of the our certification scheme is a technique for the estimation of the quantity

with n the total input photon number. As shown in the Methods section, for all target states  , F(n) is a lower bound on the fidelity F and, moreover, F(n)=F=1 if

, F(n) is a lower bound on the fidelity F and, moreover, F(n)=F=1 if  =

= . In addition, this bound is connected to a natural extremality property of Gaussian states, discussed also in the Methods section. Our test

. In addition, this bound is connected to a natural extremality property of Gaussian states, discussed also in the Methods section. Our test  , summarized in Box 1, yields an estimate F(n)* of F(n). If F(n)* is sufficiently above the threshold FT, the preparation

, summarized in Box 1, yields an estimate F(n)* of F(n). If F(n)* is sufficiently above the threshold FT, the preparation  is accepted. Otherwise it is rejected. We introduce the measurement schemes

is accepted. Otherwise it is rejected. We introduce the measurement schemes  and

and  , which depend on the specific target state, to obtain the estimate F(n)*. Gaussian states can be estimated with the scheme

, which depend on the specific target state, to obtain the estimate F(n)*. Gaussian states can be estimated with the scheme  , while linear-optical network states with

, while linear-optical network states with  . Both measurement schemes are summarized in the Methods section and described in detail in Supplementary Note 1. In turn, a fidelity bound for post-selected target states in

. Both measurement schemes are summarized in the Methods section and described in detail in Supplementary Note 1. In turn, a fidelity bound for post-selected target states in  similar to F(n) is presented in the Methods section. Its derivation, the adaptation of the test

similar to F(n) is presented in the Methods section. Its derivation, the adaptation of the test  to post-selected targets, and the corresponding measurement scheme are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

to post-selected targets, and the corresponding measurement scheme are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

Our theorems guarantee that the test from Box 1 is indeed a certification test and give a bound on the scaling of the number of samples that are needed for the test. To state them, we introduce some notation related to mode space descriptions of linear-optical networks first. Any Gaussian unitary transformation  on Hilbert space can be represented by

on Hilbert space can be represented by

an affine symplectic transformation in mode space, that is, by a symplectic matrix  followed by a phase-space displacement

followed by a phase-space displacement  (see equation (25) in the Methods section), where the real-symplectic group

(see equation (25) in the Methods section), where the real-symplectic group  contains all real 2m × 2m matrices that preserve the canonical phase-space commutation relations42,43. By virtue of the Euler decomposition42,45, S can be implemented with single-mode squeezing operations and passive mode transformations. We denote the maximum single-mode squeezing of S by smax and define the mode range d≤m to be the maximal number of input modes to which each output mode is coupled (for details see Supplementary Note 1). Also, it will be useful to define

contains all real 2m × 2m matrices that preserve the canonical phase-space commutation relations42,43. By virtue of the Euler decomposition42,45, S can be implemented with single-mode squeezing operations and passive mode transformations. We denote the maximum single-mode squeezing of S by smax and define the mode range d≤m to be the maximal number of input modes to which each output mode is coupled (for details see Supplementary Note 1). Also, it will be useful to define

The displacement x can be implemented by a single-mode displacer at each mode j∈[m], with amplitude (x2j−1, x2j), where xk, for k∈[2m], is the kth component of x. The vector 2-norm is denoted by  , that is,

, that is,  .

.

We take σi to be a uniform upper bound on the variances of any product of i phase-space quadratures in the state  . If

. If  is Gaussian, then σ1 and σ2 are functions of the single-mode squeezing parameters of

is Gaussian, then σ1 and σ2 are functions of the single-mode squeezing parameters of  . In addition, we call

. In addition, we call  the maximal ith variance of

the maximal ith variance of  . Finally, we use the Landau symbol O to denote asymptotic upper bounds.

. Finally, we use the Landau symbol O to denote asymptotic upper bounds.

Theorem 2 (Quantum certification of Gaussian states). Let FT<1 be a threshold fidelity, α>0 a maximal failure probability, and 0<ɛ≤(1−FT)/2 an estimation error. Let  have maximum single-mode squeezing smax⩾1, mode range d≤m, and displacement x. Test

have maximum single-mode squeezing smax⩾1, mode range d≤m, and displacement x. Test  from Box 1 is a certification test for

from Box 1 is a certification test for  and requires at most

and requires at most

copies of a preparation  with first and second variance bounds σ1>0 and σ2>0, respectively.

with first and second variance bounds σ1>0 and σ2>0, respectively.

Theorem 3 (Quantum certification of linear-optical network states). Let FT<1 be a threshold fidelity, α>0 a maximal failure probability, and 0<ɛ ≤(1−FT)/2 an estimation error. Let  have mode range d ≤m. Test

have mode range d ≤m. Test  from Box 1 is a certification test for

from Box 1 is a certification test for  and requires at most

and requires at most

copies of a preparation  with maximal 2(n+1)-th variance σ≤2(n+1), where λ>0 is an absolute constant.

with maximal 2(n+1)-th variance σ≤2(n+1), where λ>0 is an absolute constant.

The proofs of all our theorems are provided in the Supplementary Information. The treatment of the class  follows as a corollary of Theorem 3 and is also provided in Supplementary Note 2. Equations (8) and (9) are highly simplified upper bounds on the total number of copies of

follows as a corollary of Theorem 3 and is also provided in Supplementary Note 2. Equations (8) and (9) are highly simplified upper bounds on the total number of copies of  that

that  requires. For more precise expressions see Supplementary Lemmas 6 and 9. Note that neither of the two theorems requires any energy cut-off or phase-space truncation. While the bound in equation (9) is inefficient in n, both for the Gaussian and linear-optical cases, the number of copies of

requires. For more precise expressions see Supplementary Lemmas 6 and 9. Note that neither of the two theorems requires any energy cut-off or phase-space truncation. While the bound in equation (9) is inefficient in n, both for the Gaussian and linear-optical cases, the number of copies of  scales polynomially with all other parameters, in particular with m. Thus, arbitrary m-mode target states from the classes

scales polynomially with all other parameters, in particular with m. Thus, arbitrary m-mode target states from the classes  and

and  with constant n, are certified by

with constant n, are certified by  efficiently.

efficiently.

Interestingly, since states in  in general display negative Wigner functions, sampling from their measurement probability distributions cannot be efficiently done by the available classical sampling methods47,48,49. Furthermore, for Fock-state measurements, these distributions define BosonSampling, for which hardness results exist50 for m asymptotically lower bounded by n5.

in general display negative Wigner functions, sampling from their measurement probability distributions cannot be efficiently done by the available classical sampling methods47,48,49. Furthermore, for Fock-state measurements, these distributions define BosonSampling, for which hardness results exist50 for m asymptotically lower bounded by n5.

Also, note that there are no restrictions on  except that, in practice, to apply the theorems, one needs bounds on σ1, σ2, and σ≤2(n+1). These variances are properties of

except that, in practice, to apply the theorems, one needs bounds on σ1, σ2, and σ≤2(n+1). These variances are properties of  and are therefore a priori unknown to Arthur. However, he can reasonably estimate them from his measurements. Note that, for random variables that can take any real value, assuming that the variances are bounded is a fundamental and unavoidable assumption to make estimations from samples; and it is one that can be contrasted with the measurement results.

and are therefore a priori unknown to Arthur. However, he can reasonably estimate them from his measurements. Note that, for random variables that can take any real value, assuming that the variances are bounded is a fundamental and unavoidable assumption to make estimations from samples; and it is one that can be contrasted with the measurement results.

Robustness against preparation imperfections

To end up with, we consider certification in the sense of Fig. 1b:

Definition 4 (Robust quantum-state certification). Let  be a target state, FT<1 be a threshold fidelity, α>0 a maximal failure probability, and Δ<1−FT a fidelity gap. A test, which takes as input copies of a preparation

be a target state, FT<1 be a threshold fidelity, α>0 a maximal failure probability, and Δ<1−FT a fidelity gap. A test, which takes as input copies of a preparation  and outputs ‘accept’ or ‘reject’, is a robust certification test for

and outputs ‘accept’ or ‘reject’, is a robust certification test for  if, with probability at least 1−α, it both rejects every

if, with probability at least 1−α, it both rejects every  for which F(

for which F( ,

,  )<FT and accepts every

)<FT and accepts every  for which F(

for which F( ,

,  )⩾FT+Δ. We say that any

)⩾FT+Δ. We say that any  accepted by such a test is a certified preparation of

accepted by such a test is a certified preparation of  .

.

This definition is more stringent than Definition 1 in that it guarantees that preparations sufficiently close to  are necessarily accepted, rendering the certification robust against preparation imperfections causing fidelity deviations as large as 1−(FT+Δ). We now show that our test

are necessarily accepted, rendering the certification robust against preparation imperfections causing fidelity deviations as large as 1−(FT+Δ). We now show that our test  from Box 1 is actually a robust certification test.

from Box 1 is actually a robust certification test.

To this end, we first write  as

as

where  is an operator orthogonal to

is an operator orthogonal to  with respect to the Hilbert–Schmidt inner product, that is, such that

with respect to the Hilbert–Schmidt inner product, that is, such that  . As

. As  is assumed to be pure, it follows immediately that

is assumed to be pure, it follows immediately that  is actually a state. In fact, multiplying both sides of equation (10) by

is actually a state. In fact, multiplying both sides of equation (10) by  and taking the trace, one readily sees that decomposition in equation (10) is just another way to express the fidelity in equation (1).

and taking the trace, one readily sees that decomposition in equation (10) is just another way to express the fidelity in equation (1).

According to equation (6), the lower bound F(n) can be defined as an expectation value of the observable

with respect to  . In a similar way, we define the quantity

. In a similar way, we define the quantity

By taking the expectation value of equation (10) with respect to the observable  and using that

and using that  and F(n)≤F, one finds that

and F(n)≤F, one finds that  . The parameter

. The parameter  turns out to quantify the robustness of our certification test.

turns out to quantify the robustness of our certification test.

Theorem 5 (Robust quantum certification). Under the same conditions as in Theorems 2 and 3, test  from Box 1 is a robust certification test with fidelity gap

from Box 1 is a robust certification test with fidelity gap

Since  and FT<1, it is clear that Δ>0. On the other hand, note that

and FT<1, it is clear that Δ>0. On the other hand, note that  can in general be arbitrarily smaller than zero. This happens, for instance, for preparations for which

can in general be arbitrarily smaller than zero. This happens, for instance, for preparations for which  , with n1, n2,…,nn⩾1 and n arbitrarily large. In particular, in the limit

, with n1, n2,…,nn⩾1 and n arbitrarily large. In particular, in the limit  , it holds that Δ→1−FT, so that the certification becomes less robust with decreasing

, it holds that Δ→1−FT, so that the certification becomes less robust with decreasing  , as one would expect. In contrast, as

, as one would expect. In contrast, as  increases from −∞ to 0, the gap decreases to its minimal value Δ=2ɛ. Note that, since it depends on

increases from −∞ to 0, the gap decreases to its minimal value Δ=2ɛ. Note that, since it depends on  ,

,  cannot be directly estimated from measurements on

cannot be directly estimated from measurements on  alone. However, Theorem 5 guarantees the existence of an entire closed convex set of states around

alone. However, Theorem 5 guarantees the existence of an entire closed convex set of states around  that are rightfully accepted and Δ lower bounds the size of that region. Furthermore, in experimentally relevant situations,

that are rightfully accepted and Δ lower bounds the size of that region. Furthermore, in experimentally relevant situations,  is expected to be small, meaning that Δ is close to its optimal value 2ɛ.

is expected to be small, meaning that Δ is close to its optimal value 2ɛ.

Finally, a statement equivalent to Theorem 5 for target states  follows as an immediate corollary of it and is Supplementary Note 2.

follows as an immediate corollary of it and is Supplementary Note 2.

Discussion

Large-scale photonic quantum technologies promise important scientific advances and technological applications. So far, considerably more effort has been put into their realization than into the verification of their correct functioning and reliability. This imposes a serious obstacle for further experimental advance, specifically in the light of the speed at which progress towards many-mode architectures takes place. Here we have presented a practical reliable certification tool for a broad family of multimode bosonic quantum technologies.

We have proven theorems that upper bound the number of experimental runs sufficient for our protocol to be a certification test. Our theorems provide large-deviation bounds from a simple extremality-based fidelity lower bound that is interesting in its own right. Our theorems hold only for statistical errors, but the stability analysis on which they rely (see Supplementary Lemmas 5 and 8) holds regardless of the nature of the errors. In Supplementary Note 5, we show that our fidelity estimates are robust also against small systematic errors.

From a more practical viewpoint, our test allows one to certify the state preparations of most current optical experiments, in both the ‘continuous-variable’ and the ‘discrete-variable’ settings. This is achieved under the minimal possible assumptions: namely, only that the variances of the measurement outcomes are finite. Thus, the certification is as unconditional as the fundamental laws of statistics allow. In particular, no assumption on the type of noise is made. Despite the rigorous bounds on the estimation errors and failure probabilities, our methods are both experimentally friendly and resource efficient.

Notably, our test can efficiently certify multimode negative-Wigner-function states that define, via local measurements, sampling problems whose classical simulation is not known to be efficient47,48,49. For instance, it can be applied to the certification of optical circuits of the type used in BosonSampling: There, m-mode Fock-basis states of n photons are subjected to a linear-optical network described by a random unitary Û drawn from the Haar measure50 and, subsequently, each output mode is measured in the Fock basis. While the question of the certification of the classical outcomes of such samplers without assumptions on the device is still largely open20,21, with the methods described here the premeasurement non-Gaussian quantum outputs of BosonSampling devices14,15,16,17 can be certified reliably and, for constant n, even efficiently. In this sense, this work goes significantly beyond previously proposed schemes to rule out particular cheating strategies by the prover21,22,23,24. Furthermore, a variety of non-Gaussian states paradigmatic in quantum optics and quantum information are also covered by our protocol (see Supplementary Note 2 for details). These include, for instance, linear-optical network outputs post-selected though photon-number measurements, ranging from both photon-added or -subtracted linear-optical network states36,37,38,39 to all the states preparable with Knill–Laflamme–Milburn-like schemes40,41. For all such states, our test is efficient in the inverse post-selection success probability  .

.

The present method constitutes a step forward in the field of photonic quantum certification, with potential implications on the certification of other many-body quantum-information technologies. Apart from that of BosonSamplers and optical schemes with post-selection, the efficient and reliable certification of large-scale photonic networks as those used, for instance, for multimode Gaussian quantum-information processing12,13, non-Gaussian Anderson-localization simulations18,19, and quantum metrology1, with a constant number of input photons, is now within reach.

Methods

Fidelity lower bound

Here we formalize the extremality notion and derive a lower bound on the fidelity F for non post-selected target states. All the non post-selected target states we consider are of the form

where  is an arbitrary Gaussian unitary and

is an arbitrary Gaussian unitary and  an arbitrary Fock-basis state. First, we derive a fidelity lower bound for general states of the form given in equation (14) and then consider the linear-optical and Gaussian cases separately. Lower bounds for the post-selected target states are provided further below in the Measurement Scheme.

an arbitrary Fock-basis state. First, we derive a fidelity lower bound for general states of the form given in equation (14) and then consider the linear-optical and Gaussian cases separately. Lower bounds for the post-selected target states are provided further below in the Measurement Scheme.

We start recalling that

where  is the creation operator of the jth mode. Its Hermitian conjugated

is the creation operator of the jth mode. Its Hermitian conjugated  is the corresponding annihilation operator. These operators satisfy

is the corresponding annihilation operator. These operators satisfy  , where δj,j′ denotes the Kronecker delta of j and j′, and

, where δj,j′ denotes the Kronecker delta of j and j′, and  , for all j, j′∈[m]. The fidelity in equation (1) can be written as

, for all j, j′∈[m]. The fidelity in equation (1) can be written as  , where

, where  is the Heisenberg representation of

is the Heisenberg representation of  with respect to

with respect to  . With this, equation (15), and the cyclicality property of the trace, we obtain that

. With this, equation (15), and the cyclicality property of the trace, we obtain that

where

is a (not necessarily normalized) positive-semidefinite operator.

To lower bound  , we consider the expectation value

, we consider the expectation value  . We write for the identity operator. From the facts

. We write for the identity operator. From the facts  and

and  , it follows that

, it follows that

and hence,

For  =

= it holds that

it holds that  and

and  . Thus, for

. Thus, for  =

= the inequality in equation (18) becomes an equality and, therefore, the bound in equation (19) is then saturated, as announced earlier.

the inequality in equation (18) becomes an equality and, therefore, the bound in equation (19) is then saturated, as announced earlier.

Next, we define the operator valued Pochhammer-symbol

for any integer t⩾0, and p−1(x):=1. In Supplementary Note 6 we show that

and

Inserting equation (17) into equation (19), using the cyclicity property of the trace, grouping the operators of each mode together, using equation (21a) and equation (21b), and that  , we obtain the general fidelity lower bound

, we obtain the general fidelity lower bound

where n! :=n1!n2!…nm!.

In order to specialize to the linear-optical case  , we take n=1n, i.e., nj=1 for all j∈[n] and nj=0 otherwise. With this, F(n) in equation (22) simplifies to the bound F(n) in equation (6). Finally, to restrict it to the Gaussian case

, we take n=1n, i.e., nj=1 for all j∈[n] and nj=0 otherwise. With this, F(n) in equation (22) simplifies to the bound F(n) in equation (6). Finally, to restrict it to the Gaussian case  , we take nj=0 for all j∈[m]. This yields the particularly simple expression

, we take nj=0 for all j∈[m]. This yields the particularly simple expression

The last expression manifests the above-mentioned connection between our fidelity lower bound and an intuitive extremality property of Gaussian states. Namely, the lower the average number of photons of  is, the closer to the vacuum it must be and, therefore, the closer

is, the closer to the vacuum it must be and, therefore, the closer  to the target state

to the target state  .

.

Arthur does not have, in general, enough quantum capabilities to directly estimate  by undoing the operation Û on Merlin’s outputs and then measuring

by undoing the operation Û on Merlin’s outputs and then measuring  in the Fock-state basis. However, we show in the next section that he can efficiently obtain

in the Fock-state basis. However, we show in the next section that he can efficiently obtain  , as well as the expectation values in equations (22) and (6), from the results of single-mode homodyne or heterodyne measurements.

, as well as the expectation values in equations (22) and (6), from the results of single-mode homodyne or heterodyne measurements.

Measurement scheme

First, we introduce some notation. By  and

and  we denote, respectively, the conjugated position and momentum phase-space quadrature operators of the jth mode in the canonical convention42,43, that is, with the commutation relations

we denote, respectively, the conjugated position and momentum phase-space quadrature operators of the jth mode in the canonical convention42,43, that is, with the commutation relations  . The particle number operator of the jth mode can be written in terms of the phase-space quadratures as

. The particle number operator of the jth mode can be written in terms of the phase-space quadratures as  . In addition, it will be convenient to group all quadrature operators into a 2m-component column vector

. In addition, it will be convenient to group all quadrature operators into a 2m-component column vector  , with elements

, with elements

As already mentioned, the action of Û on mode space is given by a symplectic matrix  and a displacement vector

and a displacement vector  . More precisely, under a Gaussian unitary Û,

. More precisely, under a Gaussian unitary Û,  transforms according to the affine linear map42

transforms according to the affine linear map42

Equivalently, the right-hand side of this equation defines the Heisenberg representation of  with respect to Û. In addition, it will be useful to denote the Heisenberg representation of

with respect to Û. In addition, it will be useful to denote the Heisenberg representation of  with respect to Û† by

with respect to Û† by  . Thanks to equation (25), we can write

. Thanks to equation (25), we can write  in terms of the symplectic matrix S and displacement vector x that define Û, as

in terms of the symplectic matrix S and displacement vector x that define Û, as

The symbols  and

and  will represent, respectively, the scalar products of

will represent, respectively, the scalar products of  and

and  with themselves. Also, we will use the same notation for the Heisenberg representations of each quadrature operator with respect to Û†, that is,

with themselves. Also, we will use the same notation for the Heisenberg representations of each quadrature operator with respect to Û†, that is,  and

and  .

.

Next, for β∈{0, n, n}, we express our fidelity bounds in the general form

where  is an observable decomposed explicitly in terms of the local observables to which Arthur has access. We start with the Gaussian case

is an observable decomposed explicitly in terms of the local observables to which Arthur has access. We start with the Gaussian case  . To express the bound of equation (23) as in equation (27), we first write the total photon-number operator as

. To express the bound of equation (23) as in equation (27), we first write the total photon-number operator as

This, in combination with equation (23), yields

Note that, due to equation (26), each component of  is a linear combination of at most 2m components of

is a linear combination of at most 2m components of  . This implies that Arthur can obtain

. This implies that Arthur can obtain  by measuring at most 2m single-quadrature expectation values of the form

by measuring at most 2m single-quadrature expectation values of the form  and 4m2 second moments of the form

and 4m2 second moments of the form  . He can then classically efficiently combine them as dictated by S and x in equation (26). In Supplementary Note 1, we give the details of this measurement procedure, which we call

. He can then classically efficiently combine them as dictated by S and x in equation (26). In Supplementary Note 1, we give the details of this measurement procedure, which we call  , and show that measuring mκ second moments, instead of 4m2, is actually enough. Furthermore, in Supplementary Note 4, we show that only m+3 experimental settings suffice if homodyne detection is used and a single setting if heterodyne detection is used.

, and show that measuring mκ second moments, instead of 4m2, is actually enough. Furthermore, in Supplementary Note 4, we show that only m+3 experimental settings suffice if homodyne detection is used and a single setting if heterodyne detection is used.

Now, proceeding in a similar manner with the generic bound of equation (22), we obtain

Note that the observable in equation (29) is contained as the special case n=0. For target states in the class  , Û is assumed to be a passive Gaussian unitary. Such unitaries preserve the area in phase-space, that is, if

, Û is assumed to be a passive Gaussian unitary. Such unitaries preserve the area in phase-space, that is, if  it holds that

it holds that  (for details, see Supplementary Note 1). Hence, using this and specialising to the case n=1n, equation (30) simplifies to

(for details, see Supplementary Note 1). Hence, using this and specialising to the case n=1n, equation (30) simplifies to

Again by virtue of equation (26), Arthur can now obtain the expectation values of the observables in equations (30) and (31) by measuring 2jth moments of the form  and then classically recombining them, which—for constant n—he can do efficiently. In Supplementary Note 1, we give the details of the measurement procedure to obtain F(n), which we call

and then classically recombining them, which—for constant n—he can do efficiently. In Supplementary Note 1, we give the details of the measurement procedure to obtain F(n), which we call  . In particular, we show that, to obtain

. In particular, we show that, to obtain  , estimating a total of O(m(4d2+1)n) 2jth moments, with j∈[n+1], is enough. Also, we list which moments are the relevant ones in terms of

, estimating a total of O(m(4d2+1)n) 2jth moments, with j∈[n+1], is enough. Also, we list which moments are the relevant ones in terms of  . Furthermore, in Supplementary Note 4, we show that a single heterodyne experimental setting throughout suffices here too.

. Furthermore, in Supplementary Note 4, we show that a single heterodyne experimental setting throughout suffices here too.

Finally, in Supplementary Note 2, we derive a bound analogous to that of equations (27) and (31) for post-selected target states  . More precisely, we show that the fidelity

. More precisely, we show that the fidelity  between

between  and an arbitrary, unknown (m−a)-mode system preparation

and an arbitrary, unknown (m−a)-mode system preparation  is lower bounded as

is lower bounded as

Actually, the bound holds not only for target states  projected onto

projected onto  but also for the more general target states of equation (14), with Û any Gaussian unitary and

but also for the more general target states of equation (14), with Û any Gaussian unitary and  any Fock-basis state, projected onto any generic a-mode pure product state on

any Fock-basis state, projected onto any generic a-mode pure product state on  . Apart from being experimentally more relevant, linear-optical network target states post-selected with Fock-basis measurements possess the peculiarity that the corresponding bound is tight for perfect preparations. That is, for these states, if

. Apart from being experimentally more relevant, linear-optical network target states post-selected with Fock-basis measurements possess the peculiarity that the corresponding bound is tight for perfect preparations. That is, for these states, if  then

then  , just as in the cases without post-selection.

, just as in the cases without post-selection.

Non-Gaussian state nullifiers

It is instructive to mention that the observables

for j∈[m], correspond to the so-called nullifiers of the Gaussian states in  . The nullifiers are commuting operators that, despite originally introduced51 as a tool to define Gaussian graph states, can be tailored to define any pure Gaussian state52,53: If a state is the simultaneous null-eigenvalue eigenstate of all m nullifiers of a given pure Gaussian state, then the former is necessarily equal to the latter. The bound F(0), given by equations (27) and (29), exploits the fact that if a preparation gives a sufficiently low expectation value for the sum

. The nullifiers are commuting operators that, despite originally introduced51 as a tool to define Gaussian graph states, can be tailored to define any pure Gaussian state52,53: If a state is the simultaneous null-eigenvalue eigenstate of all m nullifiers of a given pure Gaussian state, then the former is necessarily equal to the latter. The bound F(0), given by equations (27) and (29), exploits the fact that if a preparation gives a sufficiently low expectation value for the sum  of all m nullifiers, then its fidelity with the target state must be high. A similar intuition has been previously exploited12,13 to experimentally check for multimode entanglement of ultralarge Gaussian cluster states. Here we cannot only certify entanglement but the quantum state itself.

of all m nullifiers, then its fidelity with the target state must be high. A similar intuition has been previously exploited12,13 to experimentally check for multimode entanglement of ultralarge Gaussian cluster states. Here we cannot only certify entanglement but the quantum state itself.

Analogously, in the non-Gaussian case, from the derivation of equation (30) and the fact that

equals 1 for  =

= , we can identify the observable

, we can identify the observable

as the jth nullifier of the m-mode non-Gaussian state  of equation (14). Indeed, all m observables given by equation (36) for all j∈[m] commute and have

of equation (14). Indeed, all m observables given by equation (36) for all j∈[m] commute and have  as their unique, simultaneous null-eigenvalue eigenstate. To end up with, due to the projection onto

as their unique, simultaneous null-eigenvalue eigenstate. To end up with, due to the projection onto  , the equivalent observables for

, the equivalent observables for  do not in general commute. Nevertheless, their linear combination given by

do not in general commute. Nevertheless, their linear combination given by  still defines an observable with

still defines an observable with  as its unique null-eigenvalue eigenstate. These observables constitute, to our knowledge42,52,53, the first examples of nullifiers for non-Gaussian states.

as its unique null-eigenvalue eigenstate. These observables constitute, to our knowledge42,52,53, the first examples of nullifiers for non-Gaussian states.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Aolita, L. et al. Reliable quantum certification of photonic state preparations. Nat. Commun. 6:8498 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9498 (2015).

References

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Advances in quantum metrology. Nat. Photon. 5, 222–229 (2011).

Nielsen, M. & Chuang, I. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information Cambridge Univ. Press (2000).

Schindler, P. et al. Experimental repetitive quantum error correction. Science 332, 1059–1061 (2011).

Barends, R. et al. Superconducting quantum circuits at the surface code threshold for fault tolerance. Nature 508, 500–503 (2014).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Goals and opportunities in quantum simulation. Nat. Phys. 8, 264–266 (2012).

Aspuru-Guzik, A. & Walther, P. Photonic quantum simulators. Nat. Phys. 8, 285–291 (2012).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Nascimbéne, S. Quantum simulations with ultra-cold quantum gases. Nat. Phys. 8, 267–276 (2012).

Blatt, R. & Roos, C. F. Quantum simulations with trapped ions. Nat. Phys. 8, 277–284 (2012).

Houk, A. A., Türeci, H. E. & Koch, J. On-chip quantum simulation with superconducting circuits. Nat. Phys. 8, 292–299 (2012).

Yao, X.-C. et al. Observation of eight-photon entanglement. Nat. Photon. 6, 225–228 (2012).

Huang, Y.-F. et al. Experimental generation of an eight-photon Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger state. Nat. Commun. 2, 546 (2012).

Chen, M., Menicucci, N. C. & Pfister, O. Experimental realisation of multipartite entanglement of 60 modes of the quantum optical frequency comb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 120505–120509 (2014).

Yokoyama, S. et al. Optical generation of ultra-large-scale continuous-variable cluster states. Nat. Photon. 7, 982–986 (2013).

Spring, J. B. et al. Boson sampling on a photonic chip. Science 339, 798–801 (2013).

Tillmann, M. et al. Experimental boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 7, 540–544 (2013).

Broome, M. A. et al. Photonic boson sampling in a tunable circuit. Science 339, 794–798 (2013).

Crespi, A. et al. Integrated multimode interferometers with arbitrary designs for photonic boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 7, 545–549 (2013).

Peruzzo, A. et al. Quantum walks of correlated photons. Science 329, 1500–1503 (2010).

Crespi, A. et al. Anderson localization of entangled photons in an integrated quantum walk. Nat. Photon. 7, 322–328 (2013).

Gogolin, C., Kliesch, M., Aolita, L. & Eisert, J. Boson sampling in the light of sample complexity. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1306.3995 (2013).

Aaronson, S. & Arkhipov, A. BosonSampling is far from uniform. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1309.7460 (2013).

Spagnolo, N. et al. Experimental validation of photonic boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 8, 615–620 (2014).

Carolan, J. et al. On the experimental verification of quantum complexity in linear optics. Nat. Photon. 8, 621 (2014).

Tichy, M. C., Mayer, K., Buchleitner, A. & Molmer, K. Stringent and efficient assessment of Boson-Sampling devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 020502–020506 (2014).

Gross, D., Liu, Y.-K., Flammia, S. T., Becker, S. & Eisert, J. Quantum state tomography via compressed sensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 150401–150404 (2010).

Aharonov, D., Ben-Or, M. & Eban, E. Interactive proofs for quantum computation. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/0810.5375 (2008).

Broadbent, A., Fitzsimons, J. & Kashefi, E. Universal blind quantum computation. Proceedings of the 50th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS 2009) 517Atlanta, GA (2009).

Fitzsimons, J. & Kashefi, E. Unconditionally verifiable blind computation. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1203.5217 (2012).

Kapourniotis, T., Kashefi, E. & Datta., A. Verified delegated quantum computing with one pure qubit. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1403.1438 (2014).

Toth, G. et al. Permutationally invariant quantum tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 250403–250406 (2010).

Cramer, M. et al. Efficient quantum state tomography. Nat. Commun. 1, 149 (2010).

Flammia, S. T. & Liu, Y.-K. Direct fidelity estimation from few Pauli measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 230501–230504 (2011).

da Silva, M. P., Landon-Cardinal, O. & Poulin, D. Practical characterisation of quantum devices without tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 210404–210407 (2011).

Flammia, S. T., Gross, D., Liu, Y.-K. & Eisert, J. Quantum tomography via compressed sensing: Error bounds, sample complexity, and efficient estimators. N. J. Phys. 14, 095022–095051 (2012).

Magesan, E., Gambetta, J. M. & Emerson, J. Scalable and robust randomized benchmarking of quantum processes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 180504–180507 (2011).

Dell’Anno, F., De Siena, S., Albano, L. & Illuminati, F. Continuous-variable quantum teleportation with non-Gaussian resources. Phys. Rev. A 76, 022301–022311 (2007).

Navarrete-Benlloch, C., García-Patrón, R., Shapiro, J. H. & Cerf, N. J. Enhancing quantum entanglement by photon addition and subtraction. Phys. Rev. A 86, 012328–012336 (2012).

Dell’Anno, F. et al. Tunable non-Gaussian resources for continuous-variable quantum technologies. Phys. Rev. A 88, 043818–043830 (2013).

Eisert, J., Browne, D. E., Scheel, S. & Plenio, M. B. Distillation of continuous-variable entanglement. Ann. Phys. (NY) 311, 431–458 (2004).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Milburn, G. J. A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics. Nature 409, 46–52 (2001).

Kok, P. et al. Linear optical quantum computing with photonic qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 135–174 (2007).

Weedbrook, C. et al. Gaussian quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 621–669 (2012).

Eisert, J. & Plenio, M. B. Introduction to the basics of entanglement theory in continuous-variable systems. Int. J. Quant. Inf 1, 479–506 (2003).

Pirandola, S., Eisert, J., Weedbrook, C., Furusawa, A. & Braunstein, S. L. Advances in quantum teleportation. Nat. Photon. 9, 641–652 (2015).

Braunstein, S. L. Squeezing as an irreducible resource. Phys. Rev. A 71, 055801–055804 (2005).

Reck, M., Zeilinger, A., Bernstein, H. J. & Bertani, P. Experimental realization of any discrete unitary operator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 58–61 (1994).

Mari, A. & Eisert, J. Positive Wigner functions render classical simulation of quantum computation efficient. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 230503–230507 (2012).

Veitch, V., Ferrie, C., Gross, D. & Emerson, J. Negative quasi-probability as a resource for quantum computation. N. J. Phys. 14, 113011 (2012).

Veitch, V., Wiebe, N., Ferrie, C. & Emerson, J. Efficient simulation scheme for a class of quantum optics experiments with non-negative Wigner representation. N. J. Phys. 15, 013037 (2013).

Aaronson, S. & Arkhipov, A. The computational complexity of linear optics. Theory Comput. 9, 143 (2013).

Gu, M., Weedbrook, C., Menicucci, N. C., Ralph, T. C. & van Loock, P. Quantum computing with continuous-variable clusters. Phys. Rev. A 79, 062318–062333 (2009).

Aolita, L., Roncaglia, A., Ferraro, A. & Acín, A. Gapped two-body Hamiltonian for continuous-variable quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 090501–090504 (2010).

Menicucci, N. C., Flammia, S. T. & van Loock, P. Graphical calculus for Gaussian pure states. Phys. Rev. A 83, 042335–042357 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank F.G.S.L. Brandão and S.T. Flammia for discussions on certification of state preparation, and M. Cramer for noticing an error in a previous version of the manuscript. We thank the EU (RAQUEL, SIQS, AQuS, REQS—Marie Curie IEF No 299141), the BMBF, the FQXI, the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes, MPQ-ICFO, the Spanish project FOQUS, the Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR 875), and FOQUS for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in all the discussions and contributed with insights. L.A. conceived the fidelity bound and its estimation technique. L.A., C.G. and M.K. carried out all the calculations and worked out the details of the formalism.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1-6 and Supplementary References (PDF 331 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Aolita, L., Gogolin, C., Kliesch, M. et al. Reliable quantum certification of photonic state preparations. Nat Commun 6, 8498 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9498

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9498

This article is cited by

-

Quantum simulation of thermodynamics in an integrated quantum photonic processor

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Quantum process tomography with unsupervised learning and tensor networks

Nature Communications (2023)

-

On the optimal certification of von Neumann measurements

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Towards the standardization of quantum state verification using optimal strategies

npj Quantum Information (2020)

-

Quantum certification and benchmarking

Nature Reviews Physics (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

).

). and requests a sufficient number of copies of it.

and requests a sufficient number of copies of it. (see the Methods section), which can be done with m+3 local homodyne settings or a single local heterodyne setting throughout.

(see the Methods section), which can be done with m+3 local homodyne settings or a single local heterodyne setting throughout. (see the Methods section), which can be done with a single local heterodyne setting throughout.

(see the Methods section), which can be done with a single local heterodyne setting throughout.