Abstract

Mechanically interlocked and entangled molecular architectures represent one of the elaborate topological superstructures engineered at a molecular resolution. Here we report a methodology for fabricating mechanically selflocked molecules (MSMs) through highly efficient one-step amidation of a pseudorotaxane derived from dual functionalized pillar[5]arene (P[5]A) threaded by α,ω-diaminoalkane (DA- n; n=3–12). The monomeric and dimeric pseudo[1]catenanes thus obtained, which are inherently chiral due to the topology of P[5]A used, were isolated and fully characterized by NMR and circular dichroism spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography and DFT calculations. Of particular interest, the dimeric pseudo[1]catenane, named ‘gemini-catenane’, contained stereoisomeric meso-erythro and dl-threo isomers, in which two P[5]A moieties are threaded by two DA- n chains in topologically different patterns. This access to chiral pseudo[1]catenanes and gemini-catenanes will greatly promote the practical use of such sophisticated chiral architectures in supramolecular and materials science and technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the pioneering work by Frisch and Wasserman on chemical topology1, mechanically interlocked and entangled molecular architectures have attracted much interest because of their fascinating topological features2,3 as well as the increasing influences on materials science and nanotechnology4,5,6,7. Inspired partly by the mathematical, iconological and religious symbols, much progress has been made in the rational synthesis of the mechanically interlocked molecules (MIMs) with ever-growing complexity8,9,10,11,12,13,14. A vast variety of bi- and multi-component MIMs, including [n]rotaxanes (n≥2), [n]catenanes (n≥2) and [cn]daisy chains (n≥2)15,16,17,18, have hitherto been synthesized. In contrast, the covalently linked single-component locked molecules, which may be called mechanically selflocked molecules (MSMs)19, have sporadically been reported. Typical examples of MSMs include pseudo[1]rotaxane20,21,22, pseudo[1]catenane23,24, pretzelane25,26, double-lasso rotamacrocycle27,28 and molecular figure-of-eight29. Compared with the well-established MIMs, however, the construction of higher-order MSM systems still remains a challenge, mainly due to the lack of a convenient general synthetic route and the tremendous obstacles in both synthesis and characterization.

1-Hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT), a widely used additive for peptide synthesis30, has also been applied to the synthesis of cyclic peptides31,32, which stimulated us to employ this reagent in the synthesis of pseudo[1]catenanes and single-component MSMs through amidation.

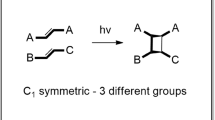

In this study, we have applied HOBT to the synthesis of a series of MSMs and found that the amidation mediated by HOBT serves as the essential step for constructing these sophisticated topologies. Intriguingly, when a long α,ω-diaminoalkane was reacted with pillar[5]arene-dicarboxylic acid in the presence of a condensation reagent (EDCI) and HOBT, a new member of the MSM family was obtained and eventually identified as a dually threaded pseudo[1]catenane, or ‘gemini-catenane’ in addition to a singly threaded pseudo[1]catenane, both of which are conformationally stable and inherently chiral.

Results

Synthetic approach to MSMs

The Pillar[5]arene (P[5]A) is a [15]paracyclophane derivative consisting of five 1,4-dialkoxybenzene units mutually connected at the 2- and 5-positions with a methylene bridge33. The circular oxygen alleys at the both portals of pillararene, analogous to crown ether, strongly bind dicationic organic and difunctional guests34,35,36,37. A1/A2-difunctionalized dimethylpillar[5]arene (DMP[5]A)38 can be prepared by the partial oxidation of DMP[5]A39,40 and subsequent modification. Exploiting these features of P[5]A, we designed A1/A2-dicarboxylato-DMP[5]A (4) as the wheel of pseudorotaxane and α,ω-diaminoalkane as the axle. As shown in Fig. 1b, 4 was prepared from 1,4-dimethoxypillar[4]arene[1]hydroquinone (3) in 81% yield through alkylation with ethyl bromoacetate and the subsequent hydrolysis. Dicarboxylic acid 4 was reacted with 1,8-diaminooctane (DA-8) in the presence of 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI·HCl) (2.5 equiv.) and HOBT (2.5 equiv.) for 48 h in CHCl3 at room temperature to afford 1a as a white solid (melting point: 290–292 °C) in 51% isolated yield. The chemical structure of 1a was fully characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR and HRMS spectroscopies and also by X-ray crystallography. In the IR spectra, the C=O stretching vibration was shifted from 1,730 cm−1 in 4 to 1,681 cm−1 in 1a, indicating formation of the amide linkage (see Supplementary Figs 53 and 54). In the 1H NMR spectra of 1a, the signals of axle methylene protons were greatly upfield-shifted to δ<0, as a consequence of the shielding effect of the pillararene’s aromatic rings (see Supplementary Fig. 5). The crystal structure of 1a (Fig. 2a) unambiguously revealed the formation of pseudo[1]catenane, in which the pillararene ring is threaded by the octamethylene chain. Since this pseudo[1]catenane is planar-chiral as is the case with pillar[5]arene, the enantiomer pair was resolved by chiral HPLC. The first and second fractions collected showed mirror-imaged circular dichroism (CD) spectra (Supplementary Figs 68 and 69) and were assigned to (pS)- and (pR)- enantiomers of pseudo[1]catenane 1a, respectively, by comparison with the theoretical CD spectra of P[5]A simulated by using the density functional theory (DFT)41.

(a) Crystal structures of 1a. (b) Crystal structures of 1d. (Both of 1a and 1d the thermal ellipsoids are at 50% probability). In the crystal structure, the hydrogen atoms of the pillararene moiety were omitted for clarity purpose; colour code: carbons in grey, hydrogens of the octamethylene moiety in white, oxygens in red and nitrogens in blue.

Interestingly, two additional products eluted by more polar solvents upon chromatographic separation were isolated in 9 and 19% yield, respectively. The HRMS analyses revealed their parent peaks in the ‘dimer’ region at m/z 1,894.9295 and 1,894.9445, respectively (see Supplementary Figs 46 and 47). Possessing exactly the twofold mass of 1a, these ‘dimeric’ products were assignable either to non-threaded 2:2 monocyclic dimers of 4 with DA-8 or to selflocked gemini-catenanes 2a and 2′a. The possibility of the non-threaded cyclodimers was immediately excluded on the basis of the unusually upfield-shifted octamethylene protons (Supplementary Fig. 29). As a natural consequence of the planar chirality of pillararene38 (Fig. 1b) and pre-assembled pseudorotaxane 4 used as a substrate in the present synthesis, the gemini-catenane generated therefrom should contain one S2-symmetric ‘erythro’ and two C2-symmetric ‘threo’ isomers. The catenane structure is obvious from the unusual upfield shifts of the octamethylene protons a−d in the 1H NMR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 29). More crucially, the two sets of protons a−d, which are equivalent to each other in 1a, are desymmetrized to give two significantly split series of protons a−d and a′−d′ in gemini-catenanes 2a and 2′a, revealing inequivalent magnetic environment for each series of the protons. Thus, the protons b−d are more deeply embedded into the pillararene cavity and suffer stronger shielding effects than the protons b′−d′ to show upfield shifts up to −1.97 p.p.m. in 2a and even to −2.33 p.p.m. in 2′a.

The 13C NMR spectra of 2a and 2′a confirm the above assignment. As can been seen from Fig. 3, the carbonyl carbon (Cx) and the two methylene carbons (Ca and Cy) adjacent to the amide group in 1a give single peaks, reflecting the equivalent magnetic environment for each of these carbons. In sharp contrast, all of the Ca, Cx and Cy signals significantly split in both 2a and 2′a, indicating that the two amide groups are no longer equivalent in these molecules due to the gemini-catenane structure.

(a) 13C NMR spectrum of 2′a (100 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C). (b) 13C NMR spectrum of 1a (100 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C). (c) 13C NMR spectrum of 2a (100 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C). The carbonyl (x) and adjacent methylene (a and y) carbons of pseudo[1]catenane 1a are magnetically equivalent and show single peaks, while those of gemini-catenanes 2a and 2′a split into two peaks, reflecting the inequivalent magnetic environment.

Chirality of gemini-catenanes

The HRMS, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectral analyses have unambiguously proven the gemini-catenane structure of 2a and 2′a, but did not allow us to discern these two stereoisomeric molecules. Nevertheless, their chiral structures and the relevant chiroptical properties enabled us not only to discern them but also to unequivocally assign their absolute configurations with the aid of circular dichroism (CD) spectra. From the symmetry point of view, gemini-catenane is either S2-symmetric (achiral) ‘erythro’ or C2-symmetric (chiral) ‘threo’, the former of which has a centre of symmetry and exists as a single meso-isomer, while the latter has no centre or plane of symmetry and therefore exists as a pair of enantiomers42,43,44. Knowing that, we performed the chiral HPLC analysis of these gemini-catenanes to find a single peak at 8.6 min for 2a but two well-separated peaks at 6.2 and 9.2 min for 2′a under the identical conditions (see Fig. 4a,b), revealing that the former is achiral erythro and the latter chiral threo. Figure 4c illustrates the UV/Vis and CD spectra of the first and second fractions of 2′a, the absolute configurations of which were assigned to pS and pR, respectively, according to the same theoretical calculation of CD spectra of P[5]A41.

(a) HPLC traces of 2a on a chiral column. (b) HPLC traces of 2′a on a chiral column. (c) UV/Vis and CD spectra of the first and second fractions. The existence of a single isomer in 2a and a pair of enantiomers in 2′a was confirmed by the chiral HPLC analyses and the mirror-imaged CD signals for the enantiomers of the latter ([pS-2′a]=[pR-2′a]=10 μM in CHCl3 at 25 °C).

Although all the attempts to crystallize the gemini-catenanes were unsuccessful, as shown in Fig. 5, the DFT calculations revealed that 2a is more stable than 2′a by 0.8 kcal mol−1. Interestingly, the Boltzmann distribution: 2′a:2a=3.7:1, evaluated by using the free energy difference, is close to relative isolated yield: 19%:9%=2.1:1 (see Supplementary Methods and references for computational details).

The geometries were optimized by using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method. M062X-D3 dispersion energy corrections are included in the reported Gibbs free energies. The Gibbs free energy of 2a is given relative to 2′a. Hydrogen atoms of pillararene components are omitted for clarity. The (pS)- and (pR)-pillar[5]arenes are shown in green and red, respectively.

Robust conformation of MSMs

In mechanically selflocked bicyclic structures, one of the incorporated macrocycles is often de-threaded from another macrocycle by aromatic ring tumbling23,24. If such de-threading took place in our molecules, the proton signals of the octamethylene chain would coalesce in 1H NMR spectra. In our case, no essential chemical shift changes were observed for any of the proton signals of pseudo[1]catenane 1a in CDCl3 even upon addition of an excess amount (10 equiv.) of competitor 1,4-dicyanobutane, which exhibits very strong binding affinities towards DMP[5]A45, and the octamethylene proton signals were consistently upfield-shifted even in more polar CD2Cl2, CD3CN and (CD3)2SO, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 30. We further performed the variable-temperature 1H NMR experiment in (CD3)2SO to find no coalescence behaviour at least up to 80 °C. In addition, no new peaks (or products) were observed in the NMR spectrum of 1a even after heating at 160 °C for 2 h. Exactly the same experiments were repeated with gemini-catenanes 2a and 2′a to show no essential changes in the NMR spectra (see Supplementary Figs 32–37), indicating that the de-threading does not occur and hence 1a, 2a and 2′a are conformationally robust. Nevertheless, there still remains the possibility of de-threading by tumbling one of the aromatic rings under extreme conditions, and hence we may describe them as pseudo[1]catenanes or endo-spirocycles.

Substrates scope with diaminoalkanes

The scope and limitations of this facile route to MSMs were explored by employing DA- n of shorter and longer methylene chain lengths (n=2–4, 6, 10 and 12). As shown in Table 1, no catenanes were obtained in the reaction of DA-2 with 4 (entry g), most probably due to the dimethylene linker, which is too short to catenate at the both ends of 4. Possessing a longer methylene chain, DA-3, DA-4 and DA-6 (entries b−d) gave the corresponding pseudo[1]catenanes 1b, 1c and 1d in progressively increasing 60, 86 and 96% yield, but no gemini-catenanes were obtained. The almost quantitative yield of 1d may be attributed to the formation of highly stable pseudorotaxane DA-6⊂4 (with a 105 M−1 order affinity46), which is driven by the appropriate linker length for catenating cyclization and the dual electrostatic interactions47 of the dicationic axle (diammoniohexane [DA-6·H2]2+) with the dianionic wheel (pillararene-dicarboxylate 42−). However, such an ammonium-carboxylate pair is not favourable for amidation, because mechanistically the amidation pair should be charge-neutral. It is likely therefore that HOBT not only mediates the intermolecular amidation, but also stabilizes the guest in the pillararene cavity by forming a hydrogen-bond between the HOBT’s nitrogen and the amino hydrogen on DA-6, as illustrated in Fig. 6. This leads to the smooth catenating amidation in the pseudorotaxane in particular for DA-6.

The use of longer diamine DA- n of n≥8 led to the sudden formation of gemimi-catenanes 2 and 2′ at the expense of pseudo[1]catenane 1 (Table 1, entries a, e, f). With increasing methylene chain length (n), the yield of 1 markedly decreased from 96% at n=6 to 51% at n=8 and eventually to 23% at n=12. Interestingly, the combined yield of 2 and 2′ was kept constant at 28–29% over n=8–12 with an appreciable preference for chiral 2′ at smaller n. This unusual phenomenon can be rationalized with the help of the X-ray crystallographic structures of 1a and 1d (Fig. 2a,b). The pillararene cavity is perfectly fitted to the methylene chain length and the inter-amino distance of DA-6, which leads to the almost quantitative yield of pseudo[1]catenane 1d. However, when a longer diamine (n≥8) is used, the first intra-complex amidation at one of the pillararene portals in the pseudorotaxane would proceed equally efficiently as shorter diamines, but the second intramolecular amidation at the other portal should be decelerated due to the longer distance between the coupling partners and the increased conformational flexibilities, which enhances the chance of intermolecular dimerization in gemini-catenane. Almost the same yields for gemini-catenanes of different chain lengths (n=8–12) seem reasonable, because the chance of encounter would be comparable if the second intramolecular amidation is slow and the concentration of mono-amidated pre-pseudo[1]catenane is comparable for the longer diamines.

Discussion

Series of novel selflocked chiral pseudo[1]catenanes and gemini-catenanes were prepared in high yields in an HOBT-mediated one-pot synthesis starting from pillar[5]arene-dicarboxylic acid and α,ω-diamine substrates. The short diamines (DA-3, DA-4 and DA-6) exclusively afforded pseudo[1]catenanes in good to excellent yields. Crucially, the use of longer diamines (DA-8, DA-10 and DA-12) enabled us to obtain a new class of MSM, that is, gemini-catenane, as a consequence of the decelerated second catenating amidation of the conformationally more flexible [1]rotaxane intermediate precursor to pseudo[1]catenane. The gemini-catenane thus produced was a mixture of meso and dl diastereomers (due to the planar chirality of the pillararenes incorporated), which were successfully separated and clearly assigned to a single erythro and an enantiomer pair of threo isomers. The amidation mediated by HOBT is rather conventional but definitely essential to the formation of both pseudo[1]catenanes and gemini-catenanes, providing a convenient but powerful tool for synthesizing interlocked and selflocked molecules with well-defined structures.

Methods

General

1,4-Dimethoxypillar[4]arene[1]hydroquinone (4DM1HQP5)39 was synthesized according to the literature procedures. Solvents were used as received or dried according to the procedures described in the literature. TLC was performed on silica gel GF254 plates. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (300–400 mesh). Melting points were measured on an RY-1A apparatus; the thermometer was not calibrated. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE AV400 (400 and 100 MHz). Signal positions were reported in part per million (p.p.m.) relative to the residual solvent peaks or to the peak of Si(CH3)4 used as an internal standard with the abbreviations s, d, m, bs, and ABq, denoting singlet, doublet, multiplet, broad singlet and AB quartet, respectively. The residual 1H peak of deuterated solvent appeared at 7.26 p.p.m. in CDCl3, at 5.32 p.p.m. in CD2Cl2, at 1.94 p.p.m. in CD3CN, and at 2.50 p.p.m. in (CD3)2SO, while the 13C peak of CDCl3 at 77.0 p.p.m. All coupling constants J are quoted in Hz. FTIR spectra were obtained with a Bruker Tensor 27 instrument. All IR samples were prepared as thin film and reported in wavenumbers (cm−1). High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on an Agilent 6520 Q-TOF LC/MS with ESI ionization. The X-ray diffraction data were collected by using a Rigaku Mercury CCD AFC10 system with monochromated Mo Kα radiation. Chiral HPLC analyses were performed on an Agilent 6890 Series instrument. The dimensions of the HPLC columns are 4.6 mm diameter, and 250 mm length. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded on a BioLogic MOS500 spectropolarimeter in a quartz cell of 10 mm light path.

For 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds, see Supplementary Figs 1–28. For the comparisons of 1H NMR spectra of the 1a, 2a and 2′a, see Supplementary Fig. 29. For the variable deuterated solvents and temperatures of 1H NMR spectra of 1a, 2a and 2′a, see Supplementary Figs 30–37. For HRMS spectra of compounds, see Supplementary Figs 38–51. For IR spectra of compounds, see Supplementary Figs 52–65. For the chiral HPLC traces and CD spectra of 1a and 2′a, see Supplementary Figs 68–74. For crystallographic data of 1a and 1d, see Supplementary Table 1. Synthetic procedures and spectroscopic and physical data of compounds see Supplementary Methods. For the DFT calculations of gemini-catenanes of 2a and 2′a, also see Supplementary Methods. For the Cartesian coordinates (Å), SCF energies and Gibbs free energies at 298 K for the optimized structures of 2a and 2′a, see Supplementary Data 1.

Syntheses of MSMs

General procedures for the syntheses of pseudo[1]catenanes and gemini-catenanes: exemplified by the reaction of pillararene-dicarboxylic acid 4 with 1,8-diaminooctane DA-8: HOBT (101 mg, 0.75 mmol) and EDCI (144 mg, 0.75 mmol) were added to a solution of 4 (251 mg, 0.30 mmol) and DA-8 (47 mg, 0.33 mmol) in chloroform (100 ml), and then the mixture was stirred for 48 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was poured into 0.1 M aqueous HCl solution. The organic layer was washed with water, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution and brine, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel eluted with CHCl3/MeOH of 200:1 to 50:1 ratio (v/v) to afford 1a as a white solid (120 mg, 51%): m.p. 290–292 °C; TLC (CHCl3:MeOH=30:1 v/v), Rf=0.65; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.97 (s, 2H), 6.87 (s, 2H), 6.84 (s, 4H), 6.80 (s, 2H), 5.85 (bs, 2H), 4.68, 4.48 (ABq, 4H, J=16.4 Hz), 3.74–3.77 (m, 34H), 3.02 (bs, 2H), 2.80 (bs, 2H), 0.58–0.72 (m, 2H), 0.29–0.44 (m, 2H), −0.79 to −0.76 (m, 4H), −1.34 to −1.25 (m, 2H), −1.48 to −1.37 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.7, 150.8, 150.2, 150.1, 148.6, 129.1, 128.5, 128.0, 127.9, 127.8, 114.2, 113.4, 113.0, 112.3, 67.4, 56.1, 55.9, 55.2, 55.0, 39.3, 29.2, 28.9, 28.7, 28.5, 26.7, 26.1; IR (KBr) νmax 3,415, 2,934, 2,853, 2,829, 1,681, 1,496, 1,464, 1,398, 1,212, 1,046, 928, 880, 856, 774, 727, 704, 646 cm−1; HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. for C55H67N2O12, 947.4694; found, 947.4670.

2a, White solid (21 mg, 9%): m.p. 294–296 °C; TLC (CHCl3:MeOH=30:1 v/v): Rf=0.57; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.86–6.97 (m, 20H), 6.73 (s, 2H), 5.08 (bs, 2H), 4.62, 4.55 (ABq, 4H, J=16.4 Hz), 4.47, 4.39 (ABq, 4H, J=16.4 Hz), 3.77–3.98 (m, 68H), 3.33 (bs, 2H), 3.23 (bs, 2H), 2.41 (bs, 2H), 1.69 (bs, 2H), 1.27 (bs, 4H), 0.62 (bs, 4H), −0.04 (bs, 4H), −1.01 (bs, 6H), −1.28 (bs, 2H), −1.97 (bs, 4H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.7, 167.1, 150.9, 150.4, 150.2, 150.1, 149.1, 148.9, 130.6, 129.3, 129.1, 128.3, 128.2, 127.9, 127.7, 127.3, 126.8, 117.7, 114.4, 113.9, 113.7, 113.2, 112.9, 112.7, 112.6, 70.0, 66.3, 56.1, 55.6, 55.5, 55.4, 55.3, 55.2, 55.1, 39.4, 38.2, 30.4, 30.3, 30.2, 29.3, 29.0, 28.8, 28.7, 28.5, 27.2, 26.0, 24.0; IR (KBr) νmax 3,412, 2,933, 2,853, 2,829, 1,727, 1,680, 1,533, 1,498, 1,465, 1,399, 1,212, 1,047, 929, 880, 855, 774, 727, 704, 647 cm−1; HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. for C110H133N4O24, 1,894.9343; found, 1,894.9295.

2′a, White solid (44 mg, 19%): m.p. 260–262 °C; TLC (CHCl3:MeOH=30:1 v/v): Rf=0.52; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.84–7.05 (m, 20H), 6.84 (s, 2H), 5.23 (bs, 2H), 4.62 (s, 4H), 4.51 (s, 4H), 3.74–3.82 (m, 68H), 3.36 (bs, 4H), 2.67 (bs, 2H), 1.71 (bs, 2H), 1.47 (bs, 4H), 0.78 (bs, 4H), −0.08 (bs, 2H), −0.15 (bs, 2H), −1.09 (bs, 2H), −1.21 (bs, 2H), −1.45 (bs, 2H), −1.55 (bs, 2H), −2.33 (bs, 4H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.5, 166.9, 150.8, 150.4, 150.2, 150.1, 150.1, 145.0, 148.4, 148.1, 129.6, 129.1, 128.9, 128.3, 127.9, 127.9, 127.7, 127.4, 127.2, 127.0, 115.9, 114.3, 113.4, 113.2, 112.8, 112.6, 112.5, 112.1, 68.1, 66.8, 55.7, 55.6, 55.4, 55.2, 55.1, 55.0, 39.7, 37.7, 30.4, 30.1, 29.1, 29.0, 28.7, 28.5, 28.2, 27.3, 26.6, 23.3; IR (KBr) νmax 3,411, 2,935, 2,854, 2,829, 1,680, 1,532, 1,498, 1,465, 1,398, 1,212, 1,046, 928, 880, 855, 774, 731, 704, 647 cm−1; HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. for C110H133N4O24, 1,894.9343; found, 1,894.9445.

Additional information

Accession codes: For OLEX of products 1a and 1d, see Supplementary Figs 66 and 67. CCDC 1016257 and CCDC 1016258 contain supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

How to cite this article: Li, S.-H. et al. Mechanically selflocked chiral gemini-catenanes. Nat. Commun. 6:7590 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8590 (2015).

References

Frisch, H. L. & Wasserman, E. Chemical topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83, 3789–3795 (1961).

Amabilino, D. B. & Perez-Garcia, L. Topology in molecules inspired, seen and represented. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1562–1571 (2009).

Forgan, R. S., Sauvage, J.-P. & Stoddart, J. F. Chemical topology: complex molecular knots, links and entanglements. Chem. Rev. 111, 5434–5464 (2011).

Balzani, V., Credi, A. & Venturi, M. Molecular devices and machines—concepts and perspectives for the nanoworld Wiley-VCH (2008).

Coskun, A., Banaszak, M., Astumian, R. D., Stoddart, J. F. & Grzybowski, B. A. Great expectations: can artificial molecular machines deliver on their promise? Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 19–30 (2012).

Stijn, F. M. et al. Functional interlocked systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 99–122 (2014).

Lewandowski, B. et al. Sequence-specific peptide synthesis by an artificial small-molecule machine. Science 339, 189–193 (2013).

Beves, J. E., Blight, B. A., Campbell, C. J., Leigh, D. A. & McBurney, R. T. Strategies and tactics for the metal-directed synthesis of rotaxanes, knots, catenanes and higher order links. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9260–9327 (2011).

Barin, G., Forgan, R. S. & Stoddart, J. F. Mechanostereochemistry and the mechanical bond. Proc. R. Soc. A 468, 2849–2880 (2012).

Hänni, K. D. & Leigh, D. A. The application of CuAAC ‘click’ chemistry to catenane and rotaxane synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1240–1251 (2010).

Pasini, D. The click reaction as an efficient tool for the construction of macrocyclic structures. Molecules 18, 9512–9530 (2013).

Liu, Y., Ke, C. -F., Zhang, H. -Y., Cui, J. & Ding, F. Complexation-induced transition of nanorod to network aggregates: alternate porphyrin and cyclodextrin arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 600–605 (2008).

Zhang, Z. -J., Zhang, H. -Y., Wang, H. & Liu, Y. A twin-axial hetero[7]rotaxane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 10834–10838 (2011).

Zhang, Z. -J., Han, M., Zhang, H. -Y. & Liu, Y. A double-leg donor–acceptor molecular elevator: new insight into controlling the distance of two platforms. Org. Lett 15, 1698–1701 (2013).

Ashton, P. R. et al. Supramolecular daisy chains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 1913–1916 (1998).

Rotzlera, J. & Mayor, M. Molecular daisy chains. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 44–62 (2013).

Bruns, C. J. et al. An electrochemically and thermally switchable donor–cceptor [c2]daisy chain rotaxane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1953–1958 (2014).

Bruns, C. J. et al. Redox switchable daisy chain rotaxanes driven by radical–radical interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4714–4723 (2014).

Hubin, T. J. & Busch, D. H. Template routes to interlocked molecular structures and orderly molecular entanglements. Coord. Chem. Rev. 200, 5–52 (2000).

Hiratani, K., Kaneyama, M., Nagawa, Y., Koyama, E. & Kanesato, M. Synthesis of [1]rotaxane via covalent bond formation and its unique fluorescent response by energy transfer in the presence of lithium ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13568–13569 (2004).

Li, H. et al. Dual-mode operation of a bistable [1]rotaxane with a fluorescence signal. Org. Lett. 15, 3070–3073 (2013).

Xia, B. & Xue, M. Design and efficient synthesis of a pillar[5]arene-based [1]rotaxane. Chem. Commun. 50, 1021–1023 (2014).

Wolf, R. et al. A molecular chameleon: chromophoric sensing by a self-complexing molecular assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 975–979 (1998).

Ogoshi, T., Akutsu, T., Yamafuji, D., Aoki, T. & Yamagishi, T. Solvent- and achiral-guest- triggered chiral inversion in a planar chiral pseudo[1]catenane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8111–8115 (2013).

Liu, Y., Bonvallet, P. A., Vignon, S. A., Khan, S. I. & Stoddart, J. F. Donor–acceptor pretzelanes and a cyclic bis[2]catenane homologue. Angew. Chem. Int.Ed. 44, 3050–3055 (2005).

Han, M. et al. [2]Catenane and pretzelane based on Sn-porphyrin and crown ether. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7271–7277 (2011).

Romuald, C., Arda, A., Clavel, C., Jimenez-Barbero, J. & Coutrot, F. Tightening or loosening a pH-sensitive double-lasso molecular machine readily synthesized from an ends-activated [c2]daisy chain. Chem. Sci. 3, 1851–1857 (2012).

Romuald, C., Cazals, G., Enjalbal, C. & Coutrot, F. Straightforward synthesis of a double-lasso macrocycle from a nonsymmetrical [c2]daisy chain. Org. Lett. 15, 184–187 (2013).

Boyle, M. M. et al. Stereochemistry of molecular figures-of-eight. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 10312–10323 (2012).

El-Faham, A. & Albericio, F. Peptide coupling reagents, more than a letter soup. Chem. Rev. 111, 6557–6602 (2011).

Hemantha, H. P., Narendra, N. & Sureshbabu, V. V. Total chemical synthesis of polypeptides and proteins: chemistry of ligation techniques and beyond. Tetrahedron 68, 9491–9537 (2012).

Stolze, S. C. & Kaiser, M. Challenges in the syntheses of peptidic natural products. Synthesis 44, 1755–1777 (2012).

Ogoshi, T., Kanai, S., Fujinami, S., Yamagishi, T. & Nakamoto, Y. para-Bridged symmetrical pillar[5]arenes: their Lewis acid catalyzed synthesis and host–guest property. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5022–5023 (2008).

Cragg, P. J. & Sharma, K. Pillar[5]arenes: fascinating cyclophanes with a bright future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 597–697 (2012).

Xue, M., Yang, Y., Chi, X., Zhang, Z. & Huang, F. Pillararenes, a new class of macrocycles for supramolecular chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1294–1308 (2012).

Ogoshi, T. & Yamagishi, T. Pillar[5]- and pillar[6]arene-based supramolecular assemblies built by using their cavity-size-dependent host-guest interactions. Chem. Commun. 50, 4776–4787 (2014).

Strutt, N. L., Zhang, H., Schneebeli, S. T. & Stoddart, J. F. Functionalizing pillar[n]arenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2631–2642 (2014).

Strutt, N. L. et al. Incorporation of an A1/A2-difunctionalized pillar[5]arene into a metal− organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17436–17439 (2012).

Han, C., Zhang, Z., Yu, G. & Huang, F. Syntheses of a pillar[4]arene[1]quinone and a difunctionalized pillar[5]arene by partial oxidation. Chem. Commun. 48, 9876–9878 (2012).

Ogoshi, T. et al. Clickable di- and tetrafunctionalized pillar[n]arenes (n=5, 6) by oxidation−reduction of pillar[n]arene units. J. Org. Chem. 77, 11146–11152 (2012).

Ogoshi, T. et al. High-yield diastereoselective synthesis of planar chiral [2]- and [3]rotaxanes constructed from per-ethylated pillar[5]arene and pyridinium derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 7493–7500 (2012).

Schmieder, R., Hübner, G., Seel, C. & Vögtle, F. The first cyclodiasteromeric [3]rotaxane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 3528–3530 (1999).

Cantrill, S. J., Youn, G. J., Stoddart, J. F. & Williams, D. J. Supramolecular daisy chains. J. Org.Chem. 66, 6857–6872 (2001).

Coutrot, F., Romuald, C. & Busseron, E. A new pH-Switchable dimannosyl [c2]daisy chain molecular machine. Org. Lett. 10, 3741–3744 (2008).

Shu, X. et al. Highly effective binding of neutral dinitriles by simple pillar[5]arenes. Chem. Commun. 48, 2967–2969 (2012).

Yu, G., Hua, B. & Han, C. Proton transfer in host−guest complexation between a difunctional pillar[5]arene and alkyldiamines. Org. Lett. 16, 2486–2489 (2014).

Capici, C. et al. Selective amine recognition driven by host−guest proton transfer and salt bridge formation. J. Org. Chem. 77, 9668–9675 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the 973 Programme (2011CB932500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21432004, 21372128 and 91227107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-H.L. and H.-Y.Z. performed the experiments and analysed the topological structures of pseudo[1]catenanes and gemini-catenanes. X.X. calculated the geometries and the Gibbs free energies of the gemini-catenanes. Y.L. supervised the work and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-74, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 6539 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

The Cartesian coordinates, SCF energies, and Gibbs free energies at 298 K for the optimized structures of 2a and 2'a (TXT 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, SH., Zhang, HY., Xu, X. et al. Mechanically selflocked chiral gemini-catenanes. Nat Commun 6, 7590 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8590

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8590

This article is cited by

-

Real-time chirality transfer monitoring from statistically random to discrete homochiral nanotubes

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Construction of unique pseudo[1]rotaxanes and [1]rotaxanes based on mono-functionalized pillar[5]arene Schiff bases

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2022)

-

Convenient construction of unique bis-[1]rotaxanes based on azobenzene-bridged dipillar[5]arenes

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2022)

-

Self-assembly of bis-[1]rotaxanes based on diverse thiourea-bridged mono-functionalized dipillar[5]arenes

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2022)

-

Overtemperature-protection intelligent molecular chiroptical photoswitches

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.