Abstract

Ultrathin black phosphorus is a two-dimensional semiconductor with a sizeable band gap. Its excellent electronic properties make it attractive for applications in transistor, logic and optoelectronic devices. However, it is also the first widely investigated two-dimensional material to undergo degradation upon exposure to ambient air. Therefore a passivation method is required to study the intrinsic material properties, understand how oxidation affects the physical properties and enable applications of phosphorene. Here we demonstrate that atomically thin graphene and hexagonal boron nitride can be used for passivation of ultrathin black phosphorus. We report that few-layer pristine black phosphorus channels passivated in an inert gas environment, without any prior exposure to air, exhibit greatly improved n-type charge transport resulting in symmetric electron and hole transconductance characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) van der Waals crystals are expected to have huge impact on future technologies1. Intrinsically 2D materials have the potential to bypass major hurdles for the semiconductor industry, such as the problem of fabricating and integrating ultrathin high-quality semiconductor channels2, or achieving high-mobility transparent and flexible thin-film transistors3. Until recently, the only semiconductor materials that were known to remain stable down to a few layers were the semiconducting 2D transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs)4, for example, MoS2 and WS2. The recent reports on exfoliated ultrathin black phosphorus (bP)–or phosphorene—have introduced a new material to the family of 2D semiconductors and have aroused great excitement5,6,7,8.

Phosphorene is the second known 2D crystal besides graphene that is formed by a single chemical element and can be exfoliated from a bulk van der Waals crystal4. The monolayer has an optical band gap of 1.2 eV that decreases exponentially with increasing the number of layers to about 0.3 eV in the bulk9. Ultrathin bP has been shown to exhibit excellent semiconducting electronic properties, in particular a hole mobility consistently ranging between 10 and 400 cm2 V−1 s−1 at room temperature for devices of thickness below 10 nm, and an on–off ratio in the range 102–105 (refs 5, 6, 7, 8, 10). Unlike the semiconducting TMDCs, the band gap in bP is direct for all number of layers, which makes the material particularly promising for optoelectronic applications11. The anisotropic in-plane transport and the superconducting phase in the bulk at high pressures12,13,14 could offer further exciting directions for phosphorene research. However, initial studies have shown that exfoliated bP crystals are not fully stable at ambient conditions6,7,15. A considerable deterioration of the surface roughness 1 h after exfoliation has been observed using atomic force microscopy (AFM)6. The effect also becomes apparent under optical microscopy if the exfoliated crystals are left in air for 24 h15. Recent theoretical studies show that oxygen defects can be easily introduced under normal environmental conditions16. Currently, the disintegration of few-layer bP limits the possibility to study monolayer crystals7 and also raises the question of how surface deterioration impacts transport behaviour. A method for passivating ultrathin bP crystals without prior exposure to ambient air and without chemical precursor treatment is necessary for further studies and practical applications of phosphorene.

In the following, we report that dry transfer of both graphene and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) onto ultrathin bP exfoliated in an inert Ar gas environment preserves the pristine bP crystals and limits the degradation upon exposure to ambient air and fabrication chemicals. Using AFM and Raman spectroscopy, we show that the passivated bP crystals are preserved under ambient conditions. We fabricate bP field-effect transistors (FETs) that allow direct comparison of passivated and exposed regions of the ultrathin crystal. This allows us to access the transport properties of the pristine material and to study in situ how oxidation affects the transport properties. In situ comparison of different areas on the the same exfoliated bP crystal allows us to exclude the effect of sample-to-sample variation and bulk crystal quality. Passivated bP channels show a hugely (10- to 100-fold) improved electron mobility at room temperature resulting in symmetric electron and hole transconductance characteristics. Ambipolar behaviour is consistent with theoretical band-structure calculations of pristine bP13,17.

Results

Passivation of ultrathin bP in an inert atmosphere

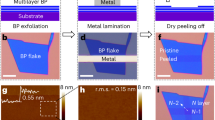

We start by cleaving and exfoliating ultrathin bP crystals onto SiO2/Si wafers using micromechanical exfoliation in an Ar-filled glovebox with an O2 and H2O concentration of less than 2 p.p.m. Crystals of thickness 3–10 nm are identified under an optical microscope in the glovebox. For the passivation of ultrathin bP, we use the dry transfer method developed for the fabrication of high-quality graphene heterostructures18,19,20. In short, either graphene or hBN is exfoliated onto SiO2/Si wafers coated with polymethylglutarimide and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), which serve as release and support polymer layers, respectively. After identifying a suitable graphene or few-layer hBN crystal, the polymethylglutarimide is developed and the passivation crystal held by the PMMA polymer layer is put on a transfer slide and brought into the glovebox. To complete the transfer, the graphene or hBN is lowered onto the exfoliated bP using a micromanipulator in the glovebox and the support PMMA layer is removed. After the transfer we observe the formation of interface bubbles (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1), which indicates a self-cleaning 2D interface between the bP and the encapsulating crystal20,21.

To demonstrate that the transfer of graphene or few-layer hBN preserves the pristine ultrathin bP crystals, we perform AFM measurements and Raman spectroscopy of adjacent exposed and protected surfaces after removing the sample from the inert gas environment. Figure 1a,b shows AFM scans of an exfoliated ∼5-nm-thick bP crystal covered with graphene and exposed to ambient air for 10 min and 24 h, respectively. From the acquired AFM images it is evident that the unprotected surface of the ultrathin bP crystal develops significant roughness, while parts of the bP that are under graphene do not show any noticeable surface change. In Fig. 1c, similar behaviour is observed for bP samples covered with hBN. In Fig. 1d,f, we compare the average surface roughness, Ra, versus time for the passivated and unprotected regions. Ra is calculated as the arithmetic average of the absolute values of the surface height deviations,  , where Δz is surface height deviation measured from the mean surface plane and N is the total number of data points in the scan. In the following, we concentrate the discussion on the sample passivated with monolayer graphene because we expect the measured Ra value to be closer to that of the underlying bP crystal. In Fig. 1d, we observe that in the first scan, 10 min after exposure to air, for the exposed surface Ra=0.43 nm compared with only 0.29 nm for the passivated. Over a period of 8 h the surface covered with graphene does not show any significant change while the Ra value for the exposed area further increases to above 2 nm. In Fig. 1e, we show the height histograms of the two studied regions. The protected part of the crystal under the graphene has a Gaussian height distribution, which preserves its form over time. Only a small shift of the average height with ∼0.5 nm is observed for the passivated region, which could be due to surface deterioration at the bottom bP surface at the SiO2 substrate. On the other hand, the exposed region has a skewed height distribution even after 10 min, which over time broadens and develops tails for heights above 8 nm, indicating the proliferation of peaks on the bP surface. Upon further exposure the roughness on the unprotected region congregates into thick droplet-like structures, which become observable under optical microscopy (Figs 1c and 2a,b). For the graphene-covered regions after 48 h in ambient conditions, degradation can be observed near the edges of the passivating crystal (Fig. 2b).

, where Δz is surface height deviation measured from the mean surface plane and N is the total number of data points in the scan. In the following, we concentrate the discussion on the sample passivated with monolayer graphene because we expect the measured Ra value to be closer to that of the underlying bP crystal. In Fig. 1d, we observe that in the first scan, 10 min after exposure to air, for the exposed surface Ra=0.43 nm compared with only 0.29 nm for the passivated. Over a period of 8 h the surface covered with graphene does not show any significant change while the Ra value for the exposed area further increases to above 2 nm. In Fig. 1e, we show the height histograms of the two studied regions. The protected part of the crystal under the graphene has a Gaussian height distribution, which preserves its form over time. Only a small shift of the average height with ∼0.5 nm is observed for the passivated region, which could be due to surface deterioration at the bottom bP surface at the SiO2 substrate. On the other hand, the exposed region has a skewed height distribution even after 10 min, which over time broadens and develops tails for heights above 8 nm, indicating the proliferation of peaks on the bP surface. Upon further exposure the roughness on the unprotected region congregates into thick droplet-like structures, which become observable under optical microscopy (Figs 1c and 2a,b). For the graphene-covered regions after 48 h in ambient conditions, degradation can be observed near the edges of the passivating crystal (Fig. 2b).

(a–b) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) scans of a 5-nm-thick bP crystal partly covered with graphene. The images are acquired, respectively, 10 min and 24 h after exposure to ambient conditions. The white dashed lines outline the passivating graphene crystal. (c) AFM scan of a 10-nm-thick bP crystal partly covered with hexagonal BN (hBN) after 5 days in ambient conditions. Scale bar, 4 μm (for all images). (d) Average roughness (Ra) versus time in ambient conditions for the passivated (blue triangles) and exposed (red squares) bP surface of the bP/graphene sample from a,b. The dashed lines are a guide to the eye. (e) Height distribution of the exposed (top) and encapsulated bP surface (bottom) at different times after exposure to ambient conditions for the bP/graphene sample from a,b. (f) Average roughness (Ra) versus time for the passivated (blue triangles) and exposed (red squares) bP surface of the bP/hBN sample from c. The dashed lines are a guide to the eye.

(a) Optical image of the bP/graphene sample from Fig. 1 after 48 h in ambient conditions. (b) Atomic force microscopy image of the bP/graphene sample after 48 h in ambient conditions. Scale bar, 4 μm (in all three images). (c) Spatial Raman map of the normalized intensity of the bP Ag1 peak. (d) Raman spectrum of the passivated region of the crystal showing the bP Ag1, B2g and Ag2 peaks, as well as the graphene G and 2D peaks. The inset shows a close up on the bP peaks.

The quality of the passivated bP is further confirmed by Raman spectroscopy 48 h after exposure to air. As can be seen from the optical image in Fig. 2a, at this point the exposed part of the bP is fully degraded. The spectrum in Fig. 2d verifies that the passivated region has clear Ag1, B2g and Ag2 peaks as expected for bP6,7. The Raman spectra of the top graphene or hBN layers do not change over time and are not perturbed by the underlying bP crystal, which rules out reactions between the bP and the passivating crystal (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2). Figure 2c shows a spatial Raman map of the normalized intensity of the bP Ag1 peak. It is evident that the bP peak is only present under the graphene passivation. The fully degraded part of the sample does not show any noticeable Raman signature for bP. Similar results are obtained when comparing bP samples passivated with hBN.

Transport properties

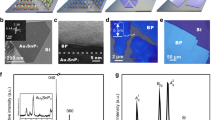

We now compare the charge transport characteristics of the passivated and exposed ultrathin bP. To fabricate devices for electrical transport measurements as a passivating layer we use few-layer insulating hBN. Contacts are deposited on both sides of the hBN strip to measure the pristine part of the bP crystal. Additional contacts are made to probe the exposed region of the same crystal for direct comparison of the electronic transport in each region. The device structure and an optical image of a typical sample are shown in Fig. 3a,b.

(a) A schematic three-dimensional illustration of the device geometry. (b) Optical image of a typical device with outlines of the ultrathin bP crystal (black dashed-dotted line) and the passivating hexagonal BN crystal (blue dashed line). Scale bar, 3 μm. (c) Four-terminal conductance versus backgate voltage (Vg) of the passivated and exposed channels of two bP FETs at source–drain bias Vsd=50 mV and temperatrure T=300 K. Sample #1 thickness ∼4.5 nm and sample #2 thickness ∼5.7 nm. For the exposed region of sample #1 and #2, the backgate voltage has been shifted by −10 and −40 V, respectively. Field-effect mobilities were extracted from the line fit (black dashed line).

Figure 3c shows four-terminal conductance against backgate voltage (Vg) at room temperature of both encapsulated and exposed regions for two devices of different thickness (sample #1 is 4.5 nm and sample #2 is 5.7 nm). For the exposed channels on the hole conduction side, at negative Vg=−70 V, the sheet conductance increases to >2 μS while at positive Vg, on the electron side, the conductance remains an order of magnitude smaller. The observation of a higher hole conductance and suppressed electron transport for the exposed region of the device is consistent with previously reported bP FETs and demonstrates dominant p-type behaviour5,6,7,8,11. In comparison, the passivated part of the device has a sheet conductance of >5 μS at Vg=70 V thereby exhibiting approximately symmetric electron and hole transconductance centred around Vg=0. In the passivated channel, the conductance on the electron side improves by a factor of more than 10, while the current in the off-state and the p-type conductance remain largely unchanged except for a negative shift in the relative doping level by ΔVg∼30 V. The shift of the threshold voltage in the exposed channels on the hole conduction side indicates a p-doping of the ultrathin bP upon exposure to ambient air. The observed p-doping of the exposed channel is consistent with recent studies on the effect of exposure to air in non-passivated and thin-capped bP samples22,23.

From the four-terminal conductance in Fig. 3, we estimate the field-effect mobility using

Here Cg is the backgate capacitance, G is the electrical conductance, W and L are, respectively, the length and width of the channel. The SiO2 backgate does not allow us to fully reach the conduction bands and linear transport regime (dG/dVg=const.), so the actual mobility of our devices at room temperature is expected to be higher than what we estimate here (see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 3). On the hole side of our devices the mobility is in the region μFE>10 cm2 V−1 s−1 at room temperature for both the passivated and exposed channel. At T=200 K, we obtain hole mobility of 118 cm2 V−1 s−1 for the exposed channel and 86 cm2 V−1 s−1 for the passivated channel. These values are consistent with what has been previously reported for a bP FET of similar thickness5,7. The 40% higher hole mobility extracted in the exposed region is due to the fact that the channel is more p-doped due to oxidation and this allows to reach further into the valance band (see Supplementary Fig. 3). In the passivated channel, at positive Vg, the improved electron conductance leads to significantly improved electron mobility. At room temperature, we obtain μFE>10 cm2 V−1 s−1 on the electron side while the values in the exposed region remain 10 to 100 times lower. At T=200 K in the passivated channel, we obtain an electron mobility of 62 cm2 V−1 s−1, while the values in the exposed region do not exceed 5 cm2 V−1 s−1. An enhancement of electron transport for the passivated channels has been reproduced in all measured samples and the direct comparison with the exposed region clearly demonstrates the effect of the passivation (see Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 4).

In the passivated bP channels at room temperature we observe hysteresis in the conductance depending on the Vg sweep direction (see Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Note 5), which is similar to that in the exposed regions and previous reports6. This suggests that the hysteresis is largely caused by charge traps at the bP/SiO2 interface rather than the degradation of the top surface. We now turn to Fig. 4 and the I–V characteristic of sample #2 from Fig. 3. To exclude the effect of the gate sweep hysteresis, the following discussion is based on transport measurements at 200 K (see Supplementary Fig. 5). In Fig. 4a, we plot the two-terminal conductance versus Vg for the passivated and exposed channels at source–drain voltage Vsd=50 mV. In the passivated channel we observe symmetric electron and hole transport as discussed above. The on–off ratio is ∼105 and is limited by the gate leakage current. At negative Vg the I–V characteristic of both the passivated and exposed channels shows slight deviations from linearity (Fig. 4b), which indicates the presence of a Schottky barrier between the metal contact and the bP. On the electron conduction side the I–V characteristic of the passivated and exposed channels is markedly different. In Fig. 4d, a Schottky behaviour is observed for the exposed channel. In contrast, on the electron side of the passivated bP, for Vsd up to ∼0.5 V, we measure a linear dependence of Isd with Vsd (Fig. 4c). The resistance in this regime decreases with increasing Vg, as expected for a FET operating as a variable resistor in linear mode. For Vsd above ∼0.5 V, we see the onset of current saturation indicating a pinch off in the conduction channel. In the saturation regime the device exhibits a residual linear increase of Isd with Vsd, which is independent of the gate voltage. From the output conductance gd=∂Isd/∂Vsd in the saturation regime (shown in the inset of Fig. 4c), we determine a finite drain output resistance of ∼106 Ω.

(a) Two-terminal sheet conductance versus backgate voltage (Vg) of sample #2 from Fig. 3 for the passivated (solid blue curve) and exposed (solid red curve) channel at temperature T=200 K. (b) I–V characteristic of the device on the hole side for the passivated (solid blue curve) and exposed (solid red curve) channel taken at gate voltages Vg=−60 V and Vg=−50 V indicated by a vertical black line in a. (c) Source–drain current (Isd) versus source–drain voltage (Vsd) for the passivated channel on the electron conduction side at Vg from +30 to +75 V in steps of 5 V (solid curves). The inset shows the output conductance ∂Isd/∂Vsd at Vg=+75 V, Vg=+65 V and Vg=+55 V. (d) Isd versus Vsd for the exposed region on the electron conduction side at Vg from +30 to +75 V in steps of 5 V.

The improved electron conductance and field-effect mobility, together with the presence of a linear and saturation regime in the I–V characteristic at positive Vg, demonstrate the formation of a clear electron conduction channel and the operation of the passivated bP device in electron accumulation. It is unlikely that the improved electron transport is due to differences in the electrical contact and Schottky barrier height, because the metal electrodes for probing both the passivated and exposed channels are deposited on exposed parts of the bP crystal under the same fabrication conditions. Therefore, we propose that the response of the passivated channel corresponds to the behaviour of pristine bP, while the transport in the exposed channel is affected by degradation consistent with the AFM and Raman spectroscopy observations. The major hallmarks of the degradation in the exposed channel are the deterioration of transport on the electron side, moderate p-doping and essentially unaffected transport on the hole side. These transport results suggest the formation of electron traps in the exposed bP, such that under positive electrostatic gating the Fermi level cannot be shifted to the conduction band. Electron traps in ultrathin bP could be induced by oxygen point defects16 (see Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 6) or the oxygen/water redox couple, which is known to suppress electron conduction in carbon nanotube FETs24.

Discussion

In summary, we have shown that the dry transfer of graphene and hBN can be used to passivate ultrathin bP prior to any exposure to ambient atmosphere. By AFM and Raman spectroscopy we have shown that the passivation preserves the pristine bP surface, which normally degrades in ambient air. Ultrathin bP devices that are exfoliated in an inert Ar gas environment and are passivated with hBN prior to any exposure to air exhibit greatly enhanced electron transport, resulting in ambipolar charge transport The fact that in the passivated samples the hole mobility is 30% higher than the electron mobility is in good agreement with the 20–30% higher effective electron mass (mxmy)1/2 in the plane13,17. We suggest that the p-doping and low electron conduction in non-passivated bP devices could be caused by oxygen trap states or chemical byproducts of the oxidation on the top surface.

The transport results presented here make pristine bP the only 2D semiconductor crystal besides MoSe2 for which symmetric electron and hole transport has been demonstrated using a SiO2 backgate and same contact metal for both electron and hole injection25. For example, symmetric transconductance characteristics in MoS2 and most of the other TMDCs has so far been obtained only by ionic liquid gating26, a PMMA substrate27 or different contact metals for hole and electron accumulation28. The relatively high electron and hole mobilities, the large on–off ratio and the symmetric ambipolar behaviour could enable the fabrication of complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) digital logic elements using encapsulated phosphorene.

We highlight that the method for passivating exfoliated bP presented here can be used to study the pristine properties of other 2D crystals, which are unstable in air, such as metallic TMDCs and layered semiconductors like GaSe and Bi2Se3 (ref. 4). Graphene and hBN are known to be excellent gas barriers29,30 and their ultrathin character allows minimum interference with the properties of the underlying crystal. Furthermore, the dry transfer in an inert gas environment does not require any chemical precursors or exposure to water, which is often the case for atomic layer deposition or other thin-film deposition techniques. Here we have performed a comparative study of partly passivated samples, but for future applications our method needs to be further developed to allow electrical contact to fully passivated devices.

Methods

Sample preparation

bP crystals were purchased from smart-elements GmbH and exfoliated onto <100> Si wafers with a 300-nm thermal oxide in an Ar-filled glovebox with an O2 and H2O concentration of less than 2 p.p.m. No degradation of the bP crystals is observed in the Ar gas environment (see Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Note 7). Thin bP flakes were identified using an optical microscope in the glovebox. The hBN crystals used for the encapsulation were exfoliated from bulk hBN single crystals grown by a Ba-BN solvent method31. The dry transfer was performed in the glovebox by the process described in the main text. For device fabrication, a layer of PMMA is spin coated onto the bP/hBN heterostructure in the glovebox and the sample is then removed from the Ar environment for e-beam lithography and thermal evaporation of contacts (5 nm Ti and 80 nm Au).

AFM and Raman measurements

AFM scans were acquired using a Bruker Dimension FastScan microscope in tapping mode. Between the scans the bP samples were kept in a class 1,000 cleanroom with controlled 50% relative humidity. Raman spectroscopy was performed in ambient conditions in the backscattering configuration with a 532-nm laser excitation.

Electrical transport measurements

Electrical transport measurements were performed either in d.c. or using a.c. lock-in amplifiers together with a DL instruments 1211 current preamplifier at low frequency (<3 Hz). All electrical transport measurements were performed in vacuum.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Doganov, R. A. et al. Transport properties of pristine few-layer black phosphorus by van der Waals passivation in an inert atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 6:6647 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7647 (2015).

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. A roadmap for graphene. Nature 490, 192–200 (2012) .

Schwierz, F. Graphene transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 487–496 (2010) .

Nathan, A. et al. Flexible electronics: the next ubiquitous platform. Proc. IEEE 100, 1486–1517 (2012) .

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013) .

Li, L. et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 372–377 (2014) .

Koenig, S. P., Doganov, R. A., Schmidt, H., Castro Neto, A. H. & Özyilmaz, B. Electric field effect in ultrathin black phosphorus. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 103106 (2014) .

Liu, H. et al. Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano 8, 4033–4041 (2014) .

Xia, F., Wang, H. & Jia, Y. Rediscovering black phosphorus as an anisotropic layered material for optoelectronics and electronics. Nat. Commun. 5, 4458 (2014) .

Tran, V., Soklaski, R., Liang, Y. & Yang, L. Layer-controlled band gap and anisotropic excitons in few-layer black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. B 89, 235319 (2014) .

Chan, M. Y. et al. Suppression of thermally activated carrier transport in atomically thin MoS2 on crystalline hexagonal boron nitride substrates. Nanoscale 5, 9572–9576 (2013) .

Buscema, M. et al. Fast and broadband photoresponse of few-layer black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nano Lett. 14, 3347–3352 (2014) .

Jamieson, J. C. Crystal structures adopted by black phosphorus at high pressures. Science 139, 1291–1292 (1963) .

Morita, A. Semiconducting black phosphorus. Appl. Phys. A Solids Surfaces 39, 227–242 (1986) .

Kawamura, H., Shirotani, I. & Tachikawa, K. Anomalous superconductivity in black phosphorus under high pressures. Solid State Commun. 49, 879–881 (1984) .

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 1, 025001 (2014) .

Ziletti, A., Carvalho, A., Campbell, D. K., Coker, D. F. & Castro Neto, A. H. Oxygen defects in phosphorene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 046801 (2015) .

Qiao, J., Kong, X., Hu, Z.-X., Yang, F. & Ji, W. High-mobility transport anisotropy and linear dichroism in few-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 5, 4475 (2014) .

Mayorov, A. S. et al. Micrometer-scale ballistic transport in encapsulated graphene at room temperature. Nano Lett. 11, 2396–2399 (2011) .

Dean, C. R. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 722–726 (2010) .

Tan, J. Y. et al. Electronic transport in graphene-based heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 183504 (2014) .

Kretinin, A. V. et al. Electronic properties of graphene encapsulated with different two-dimensional atomic crystals. Nano Lett. 14, 3270–3276 (2014) .

Island, J. O., Steele, G. a., van der Zant, H. S. J. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. Environmental stability of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 2, 011002 (2015) .

Kim, J. et al. Toward air-stable multilayer phosphorene thin-films and transistors. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1412.0355 (2014) .

Aguirre, C. M. et al. The role of the oxygen/water redox couple in suppressing electron conduction in field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 21, 3087–3091 (2009) .

Pradhan, N. R. et al. Ambipolar molybdenum diselenide field-effect transistors: field-effect and Hall mobilities. ACS Nano 8, 7923–7929 (2014) .

Zhang, Y., Ye, J., Matsuhashi, Y. & Iwasa, Y. Ambipolar MoS2 thin flake transistors. Nano Lett. 12, 1136–1140 (2012) .

Bao, W., Cai, X., Kim, D., Sridhara, K. & Fuhrer, M. S. High mobility ambipolar MoS2 field-effect transistors: substrate and dielectric effects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 042104 (2013) .

Das, S. & Appenzeller, J. WSe2 field effect transistors with enhanced ambipolar characteristics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 103501 (2013) .

Bunch, J. S. et al. Impermeable atomic membranes from graphene sheets. Nano Lett. 8, 2458–2462 (2008) .

Koenig, S. P., Wang, L., Pellegrino, J. & Bunch, J. S. Selective molecular sieving through porous graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 728–732 (2012) .

Taniguchi, T. & Watanabe, K. Synthesis of high-purity boron nitride single crystals under high pressure by using Ba–BN solvent. J. Cryst. Growth 303, 525–529 (2007) .

Acknowledgements

B.Ö. acknowledges support by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister's Office, Singapore under its Competitive Research Programme (CRP Award No. NRF-CRP9-2011-3) and the SMF-NUS Research Horizons Award 2009-Phase II. A.H.C.N. acknowledges the NRF-CRP award ‘Novel 2D materials with tailored properties: beyond graphene’. The calculations were performed at the GRC computing facilities. A.Z. and D.F.C. acknowledge the NSF grant CHE-1301157.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Ö. initiated the research; R.A.D. and S.P.K. fabricated the samples, performed the AFM and Raman measurements and obtained initial transport results. E.C.T.O’F. performed the detailed electrical transport measurements and transport analysis presented in the article. Y.Y. helped with the transfer process. A.Z., A.C., D.K.C., D.F.C. and A.H.C.N. performed the DFT study presented in the Supplementary Information. K.W. and T.T. grew the hBN crystals used for the encapsulation. B.Ö. directed and supervised the research project. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Notes 1-7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 588 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doganov, R., O’Farrell, E., Koenig, S. et al. Transport properties of pristine few-layer black phosphorus by van der Waals passivation in an inert atmosphere. Nat Commun 6, 6647 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7647

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7647

This article is cited by

-

Tunable bandgap of black phosphorus by arsenic substitution toward high-performance photodetector

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Surface functionalization of phosphorene via P-H bond for ambient protection and robust photocatalytic H2 evolution

Science China Materials (2022)

-

Developments in stability and passivation strategies for black phosphorus

Nano Research (2021)

-

Bi2O2Se/BP van der Waals heterojunction for high performance broadband photodetector

Science China Information Sciences (2021)

-

Local electrical characterization of two-dimensional materials with functional atomic force microscopy

Frontiers of Physics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.