Abstract

Nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without a cleft palate (NSCL/P) is among the most common human congenital birth defects and imposes a substantial physical and financial burden on affected individuals. Here, we conduct a case–control-based GWAS followed by two rounds of replication; we include six independent cohorts from China to elucidate the genetic architecture of NSCL/P in Chinese populations. Using this combined analysis, we identify a new locus at 16p13.3 associated with NSCL/P: rs8049367 between CREBBP and ADCY9 (odds ratio=0.74, P=8.98 × 10−12). We confirm that the reported loci at 1q32.2, 10q25.3, 17p13.1 and 20q12 are also involved in NSCL/P development in Chinese populations. Our results provide additional evidence that the rs2235371-related haplotype at 1q32.2 could play a more important role than the previously identified causal variant rs642961 in Chinese populations. These findings provide information on the genetic basis and mechanisms of NSCL/P.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate (NSCL/P) is among the most common human congenital birth defects1. Despite improvements in surgical correction techniques, this serious malformation has lifelong implications for health and imposes a substantial financial burden on affected families2. Previous genetic and epidemiological studies clarified that the aetiology of NSCL/P is multifactorial, with both genetic and environmental factors contributing to the phenotype3,4,5.

To date, four multi-stage, well-designed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of NSCL/P have been conducted. In addition to the susceptibility gene IRF6, which was previously identified in candidate studies before the GWAS era6,7, Birnbaum et al.8 identified a key locus for NSCL/P at 8q24.21 using 686 cases and 1,337 control subjects of European ancestry. An extension of this study, which involved 401 cases and 1,323 controls in addition to independent replication in European trios, identified two additional relevant loci at 10q25.3 and 17q22 ref. 9. Beaty et al.10 applied a case–parent design to explore genome-wide transmission patterns in 825 trios of European ancestry and 1,038 trios of Asian ancestry and validated the identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with 331 Asian and 51 South Asian families, 1,149 European families and 434 South/Central American families, which resulted in the identification of two new susceptibility loci at 1p22.1 and 20q12. Subsequent validation of Beaty’s study identified three other loci at 1p36.13, 3q12.3 and 17p13 that are significantly associated with NSCL/P11. By combining the discovery phase of previous GWAS9,10, Ludwig et al.12 reported five additional loci (1p36.13, 2p21, 3p11.1, 8q21.3 and 13q31.1) that are associated with NSCL/P. These observations not only targeted multiple regions influencing the risk of NSCL/P but also suggested that European and Asian populations may have different causal variants in the same locus as a result of different genetic backgrounds2. Although these studies8,9,10,12 were well designed, they mainly focused on susceptibility loci in people of European ancestry. Some of them involved individuals from Asia10,12, but they recruited samples from different countries and only some of them included individuals from China.

Thus, to further elucidate the genetic architecture of NSCL/P in Chinese individuals and to identify new susceptibility loci for NSCL/P, we conduct a GWAS followed by two rounds of replication in a Chinese population. Using this combined analysis, we identify a new locus at 16p13.3 associated with NSCL/P: rs8049367 between CREBBP and ADCY9 (odds ratio=0.74, P=8.98 × 10−12). We confirm that the reported loci at 1q32.2, 10q25.3, 17p13.1 and 20q12 are also involved in NSCL/P development in Chinese populations.

Results

Genome-wide association analysis

In the initial discovery phase, we performed a GWAS scan in two cohorts (Huaxi and Nanjing, Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). After quality control (Supplementary Fig. 2), 842,556 autosomal SNPs were analysed (see Methods) in 858 cases and 1,248 controls (504 cases and 455 controls from the Huaxi cohort (GWAS I), and 354 cases and 793 controls from the Nanjing cohort (GWAS II)). We performed logistic regression in each cohort with adjustments for sex and the significant principal components of the corresponding cohort to test the additive effect of minor alleles of each SNP. Meta-analysis was used to combine the results of the two cohorts in the GWA scan. Because the controls in the Nanjing cohort were derived from imputed data from a previous study and did not include newborn infants, we applied a random-effect model in the meta-analysis when heterogeneity existed (P for Cochran’s Q statistic <0.05) to avoid false-positive results caused by putative population stratification or bias derived from age-based differences and imputation error. Quantile–quantile plots of genome-wide association test statistics revealed minimal inflation; thus, substantial cryptic population substructure and differing genotypic variants between the cases and controls were unlikely after meta-analysis of the two cohorts (λHuaxi=1.03, λNanjing=1.10 and λmeta=1.06, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Thirty-four SNPs exhibited consistently significant associations on analysis during the discovery phase (see Methods). Among these SNPs, 18 representative SNPs were selected for subsequent evaluation, and the other 16 were ignored because of their high linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2>0.8) with at least one of the 18 selected SNPs (see Methods, Supplementary Table 2). Coupled with an additional 11 SNPs identified in previous studies (see Methods, Table 1), we included a total of 29 SNPs in the first validation conducted in Guangzhou (validation Ia), Huaxi (validation Ib) and Nanjing (validation Ic) (see Methods, Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Replication and combined analysis

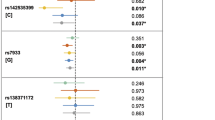

In the first round of replication, sixteen SNPs exhibited evidence of association with NSCL/P (Meta P value of validation I <0.05, Supplementary Table 3), and we then evaluated these SNPs in the Hui population (validation II), a racial minority in China. In the combined analysis of all GWAS plus the validation data, SNP mapping to 1q32.2 (rs1044516, rs742214, rs2235371, rs596731 and rs10863790), 10q25.3 (rs7078160), 16p13.3 (rs8049367), 17p13.1 (rs4791774) and 20q12 (rs13041247) exhibited evidence of association, which was statistically significant after an adjustment for multiple testing (P<5 × 10−8; Table 2; Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

Differential expression analysis

To gain further insight into the possible involvement of genes at the identified loci in the development of NSCL/P, we examined the expression pattern of nine genes that were present within 50 kb of the identified SNPs or reported by previous studies by comparing microarray expression data from NSCL/P (n=7) and control (n=6) dental pulp stem cell cultures. We found that ADCY9 and NTN1 were significantly upregulated in the dental pulp stem cultures of NSCL/P patients (PWilcoxon<0.05, Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

In this GWAS, four recognized loci were confirmed (1q32.2, 10q25.3, 17p13.1 and 20q12) and one new locus were identified (16p13.3) in the Chinese populations.

The newly identified SNP rs8049367 at 16p13.3 is located 50 kb upstream of CREBBP and 32 kb downstream of ADCY9 (Fig. 2a). CREBBP is a transcription factor that has been reported to play essential roles in embryonic development via co-activation with the protein P300 (refs 13, 14). Several studies have reported a causal relationship between deletions in the CREBBP-ADCY9 region and Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome15,16,17,18,19,20, which is characterized by distinctive facial features, including a cleft lip and palate21. Expression analysis revealed that expression of ADCY9 but not CREBBP was significantly different in dental pulp stem cell cultures from NSCL/P patients compared with the dental pulp stem cell cultures from normal controls (PWilcoxon=4.66 × 10−3 and 6.28 × 10−1, respectively, Supplementary Table 6). Thus, ADCY9 represents a potential susceptibility gene for NSCL/P. We further analysed the biological potential of the identified variant but did not observe any signals of enhancers or other regulatory elements in the regions nearby rs8049367 and its closely linked SNPs (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Notably, we found that rs2262251, which was in strong LD with rs8049367 in people of Asian ancestry (r2=0.96), is located in the exon of a newly identified long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), RP11–462G12.2 (GENCODE version 19). Therefore, we predicted an interaction between the lncRNA and two nearby genes (CREBBP and ADCY9) and found that both lncRNA–gene pairs exhibited high scores (Supplementary Table 7), which suggested potential interactions. Together, these data suggest that the genetic variants in the CREBBP-ADCY9 region influence the development of NSCL/P, possibly by regulating non-coding RNA. Additional tissue-specific expression quantitative trait loci studies are warranted to further illuminate the relationship between the variants and CREBBP-RP11–462G12.2-ADCY9.

Regional plots of association results and recombination rates for (a) 1q32.2, (b) 16p13.3, (c) 17p13.1, (d) 10q25.3 and (e) 20q12 in the GWAS discovery stage (858 cases and 1248 controls). The results (−log10P) are shown for SNPs in the region 200 kb upstream or downstream of the lead SNP. The results for validated SNPs in the GWAS stages are shown as squares and the combined results of all stages (2506 cases and 3296 controls) are shown as diamonds; the key SNPs are shown in purple and the linkage disequilibrium values (r2) for the other SNPs are indicated by the heat scale. To make the plot clearer, SNPs from the initial GWAS scan are represented by ordinary circles and the imputed SNPs are represented by stars. The red line indicates the level of genome-wide significance (Pmeta=5 × 10−8). The genes within the region of interest are annotated, and the direction of the transcripts is shown by arrows.

Before the GWAS era, IRF6 had been consistently identified as a susceptibility gene for nonsyndromic CL/P across studies1. To date, three SNPs (rs642961, rs861020 and rs10863790) near IRF6 were reported to be associated with NSCL/P in previous GWAS8,12, and rs642961 was found to be a causative variant6 in people of European ancestry. In our study, six SNPs (rs2235371, rs1044516, rs742214, rs596731, rs674433 and rs12117075) were consistently associated with NSCL/P in all three stages (Supplementary Table 4). rs2235371 was in strong LD with rs10863790, and rs674433 was in strong LD with rs642961 and rs861020 (r2Chinese>0.8). The other SNPs in the region identified in our study revealed low to moderate LD with rs2235371 (r2Chinese=0.22–0.77; Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 8). A conditional analysis of the combined all cohorts demonstrated that the effects of all identified SNPs were abolished or substantially reduced by rs2235371 (Supplementary Table 8), suggesting that these variants may represent the same causal variants. Interestingly, the SNP rs2235371, a missense variant with a functional Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score of 32, is located in a region with a regulatory element signal in hESH1-derived mesenchymal cells according to the NIH’s Roadmap Epigenomics Project (Supplementary Fig. 5). The CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) Chromatin Interaction Analysis by Paired-End Tag Sequencing (ChIA-PET) data in the Encode Project revealed an interaction signal between regulatory regions and DNA sequences containing rs2235371 in multiple cell lines, indicating that rs2235371 may be involved in chromatin activities. Thus, the effect of the variant rs2235371 may be complicated, and additional studies are warranted to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

SNP rs1880646 near NTN1 at 17p13.1 was originally reported in a GWAS by Beaty et al.10,11 and in their follow-up study. In our study, rs1880646 was not associated with NSCL/P in the GWAS stage (Pmeta=0.76), suggesting that rs1880646 may not be an appropriate proxy of causal variants at 17p13.1 in the Chinese population. Rather, our newly identified SNP, rs4791774, in the intron of NTN1 was in strong LD with SNP rs4791331, identified by Beaty et al. in Asian populations (r2=1), but not with rs1880646 (r2=0.12) (Fig. 2c). Motif analyses by HaploReg indicated that the G allele of rs4791774 could greatly alter the affinity of MYC (score: 0.5–12.5). NTN1 encodes the protein NETRIN 1, which plays a role in the developing the nervous system by promoting both axonal outgrowth and axonal guidance in pathfinding22,23,24,25. In addition, NTN1 was upregulated in dental pulp stem cell cultures from NSCL/P patients, suggesting the importance of NTN1 in the development of NSCL/P.

One of the two reported SNPs, rs7078160 at 10q25.3, is located in the intron of KIAA1598 and is downstream of VAX1 (Fig. 2d). VAX1 encodes a transcriptional regulator with a DNA-binding homeobox domain. Mouse knockouts for VAX1 develop a cleft palate, and this gene is expressed widely in developing craniofacial structures26. Nonetheless, recent target sequencing in the region of the gene failed to identify causal variants27, indicating that further attention should be devoted to the regulatory region of VAX1. Another SNP, rs13041247 at 20q12, maps 45 kb downstream of MAFB (Fig. 2e), which encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. In mice, MAFB expression was demonstrated to be high in the epithelium of the palatal shelves and in the medial edge epithelium during palatal fusion10.

Previous work has revealed evidence of heterogeneity between European and Asian populations in the identified susceptibility loci of NSCL/P. The SNP rs987525 at 8q24.21, which has recently been demonstrated to be located in the region near a remote MYC-regulated enhancer28, was not validated in either Beaty’s Asian trios10 or in our study; the derived allele is so rare in Asian populations that studies of it cannot achieve sufficient power. We screened 500-kb regions around the SNP in our imputation results; however, we did not find any SNPs with P<1.0 × 10−5 (Supplementary Fig. 6b). A similar situation occurred at rs2235371 and rs10863790 near IRF6, although these SNPs are Asian specific. In addition, our study is the first to demonstrate that the effect of rs642961, which was thought to be a causal variant in European populations, can be weakened by rs2235371, suggesting that the key variants may be located on rs2235371 in related haplotypes. In contrast to the SNPs at 8q24.21 and 1q32.2, the newly identified SNP rs8049367 tended to be shared throughout the population and to undergo positive selection; the frequency of the C allele is 68% in East Asians in contrast with only 27% in Africans and 37% in Europeans (Fst=0.113). We noted that the trend of the frequency of the C allele in people of Asian, European and African ancestries is consistent with the prevalence of NSCL/P2; thus, rs8049367 may help to explain the variable prevalence of NSCL/P in populations of different ancestries.

In this study, five loci—1q32.2, 10q25.3, 16p13.3, 17p13.1 and 20q12—were consistently identified as being associated with NSCL/P and reached genome-wide significance after combined analysis, and 16p13.3 was newly identified as an NSCL/P susceptibility region. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first GWAS performed in the Chinese population and the largest in Asia. The results of our study provide new insight into the aetiology of NSCL/P and indicate potential targets for further clinical translational research. However, the power of the study was limited because of the cost-efficient multiple stages design. Joint analysis on published GWAS is warranted to identify more loci associated with NSCL/P.

Methods

Subjects

In this study, we performed a three-stage case–control analysis, including an initial discovery phase and two validation phases (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). The discovery phase comprised 858 NSCL/P cases and 1,248 controls derived from two independent cohorts: (i) the Huaxi cohort (504 cases and 455 newborn controls) and (ii) the Nanjing cohort (354 cases and 793 controls). The first validation comprised 1,319 NSCL/P cases and 1,526 newborn controls from three independent cohorts: (i) the Guangzhou cohort (Ia: 487 cases and 496 controls); (ii) the Huaxi cohort (Ib: 503 cases and 508 controls); and (iii) the Nanjing cohort (Ic: 329 cases and 522 controls). The second validation was derived from the Ningxia Hui population, a minority nationality in China, and included 344 cases and 348 newborn controls. All participating patients were interviewed and clinically assessed by an experienced oral surgeon based on detailed diagnostic information from medical records and physical examinations to ensure that individuals with syndromic orofacial clefts or other major congenital defects were excluded. In addition, general characteristics, including age, sex, ethnicity, and birth defects, were documented. At recruitment, informed written consent was obtained from each of the participants or their guardians, and this study was approved by the institutional review boards of general hospital of Ningxia Medical University, west China hospital of stomatology Sichuan University, Nanjing Medical University and Guangdong women and children hospital.

Genotyping and quality control in GWAS

All samples from the Huaxi cohort and NSCL/P cases from the Nanjing cohort were genotyped using Affymetrix Axiom Genome-Wide CHB1 and CHB2 arrays by the CapitalBio corporation (1,280,786 SNPs); the controls from the Nanjing cohort were from a previous study29 and genotyped using an Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (905,119 SNPs). Considering that there were only approximately half a million SNPs overlapping between the two platforms, we used imputed data as a control for the Nanjing cohort. We performed a systematic quality control analysis on the raw data in each cohort before conducting the association analysis (see the workflow diagram in Supplementary Fig. 2). First, we performed basic quality control on genotyping data. SNPs were excluded if they (i) did not map to autosomal chromosomes, (ii) had a call rate of <95%, (iii) had a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <0.05 or (iv) had a genotype distribution in the controls that deviated from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P<1.0 × 10−5). Samples were excluded if they (i) had overall successful genotyping call rates <95%, (ii) had sex discrepancies between the records and the genetically inferred data or (iii) had outlying autosomal heterozygosity rates (>6 s.d. from the mean). Following the basic quality control, we extracted best-guess genotype data for SNPs with imputation quality info >0.8 and MAF >0.05 ref. 30 of sex-matched individuals from previous studies29 and combined them with the genotype data of the Nanjing cases. Next, we removed individuals who had unexpected duplicates or probable relatives (all PI_HAT >0.25). Finally, we detected population outliers using a method based on principal component analysis. Common autosomal SNPs (MAF>0.25) with a low LD (r2<0.05) in each cohort were employed to identify population outliers in the samples that had passed quality control, with Han Chinese from Bejing (CHB, N=97), Southern Han Chinese (N=100) and Japanese from Tokyo (N=89) from the 1000 Genomes Project (the Phase I integrated variant set release, v3) as the internal controls (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The Principal component analysis (PCA) suggested that the cases and controls were genetically matched and homogeneous (Supplementary Fig. 3) and that the genomic control inflation factor (λ) was 1.03 in the Huaxi cohort and 1.10 in the Nanjing cohort. After quality control procedures had been performed, 858 cases and 1,248 controls (504 cases and 455 controls in the Huaxi cohort; 354 cases and 793 controls in the Nanjing cohort) with 842,556 overlapping SNPs were included in the final analysis.

SNP selection and genotyping in the replication study

We performed a meta-analysis on the results of the two GWAS cohorts, and the following criteria were used to select SNPs for validation from the discovery phase: (i) Pmeta≤1.0 × 10−5, (ii) PHuaxi≤0.01 and PNanjing≤0.01, (iii) clear genotyping clusters and (iv) the SNP with the lowest P value was selected when multiple SNPs were observed in strong LD (r2≥0.8, Supplementary Table 2). SNPs identified in previous GWAS with Pmeta<0.05 or highly correlated SNPs with Pmeta<0.05 in the discovery phase were also included (see Table 2). rs2235371 and rs674433 met our GWAS criteria and were in high LD with published SNPs; we validated them rather than rs10863790 and rs642961(rs861020), respectively. To better explore the causal variants at 1q32.2, we included rs10863790 in the validation. As a result, 29 SNPs remained in the first validation (Supplementary Table 4). Genotyping was performed using the iPLEX MassARRAY platform (Sequenom Inc.) for two-phase validations. The primers and probes are available upon request. The laboratory technicians who performed the genotyping experiments were blinded to the case or control status.

Functional annotation and different expression analysis

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of the lead SNPs identified in our studies, we integrated chromatin biofeature annotations with 1,000 Genomes genotyping data using the Bioconductor R package FunciSNP31. The following resources were employed to filter the correlated SNPs lying within putative regulatory elements: (1) Roadmap: Chromatin Primary Core Marks Segmentation by HMM from H1 cell lines and hESH1-derived mesenchymal cells; (2) Fantom: an active, in vivo-transcribed enhancers atlas32; (3) Enhancer identified in a previously published paper33. Regional functional plot were generated by the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Correlated SNPs (r2>0.8) within a window size of 1 Mb around the newly identified SNP were used for a FunciSNP analysis. HaploReg V2 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php) was used to predict regulatory motif alteration. lncPro (http://bioinfo.bjmu.edu.cn/lncpro/) was applied to predict interactions between lncRNA and nearby proteins. Processed microarray expression data from NSCL/P (n=7) and control (n=6) dental pulp stem cell cultures were downloaded from EMBL-EBI (E-GEOD-42589). Expression measurements were performed using the Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST array, which interrogates 28,869 transcripts, followed by RNA labelling and hybridization protocols as recommended by the manufacturer34. A Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to assess differences in expression levels.

Statistical analysis

We used PLINK 1.07 (ref. 35) and R 2.15.1 (http://www.r-project.org/) for general statistical analysis. The population structure was evaluated by PCA using the EIGENSTRAT 3.0 software package36. Associations between SNP genotypes and disease status were assessed in an additive model using logistic regression model (1 degree of freedom) with adjustment(s) for sex (and significant principle components in GWAS). A meta-analysis-based method was applied to combine the results from different cohorts. A fixed-effect model with inverse variance weighting was used when there was no indication of heterogeneity (P for Cochran’s Q statistic >0.05); otherwise, a random-effect model for the corresponding SNPs was adopted. The genomic inflation factor for meta-analysis was estimated on SNPs without heterogeneity. A Manhattan plot of –log10P was generated using the ggplot2 package37 in R 2.15.1. Non-genotyped SNPs were imputed in the GWAS discovery samples using Shapeit v2 (http://www.shapeit.fr/, phasing step) and IMPUTE2 (http://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/impute/impute_v2.html, imputation step) based on haplotype information from the 1,000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org) (the Phase I integrated variant set release, v3, across 286 Asians). Regional plots were generated using LocusZoom 1.3 Standalone38. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using an additive model in logistic regression analyses, except where otherwise specified.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sun, Y. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new susceptibility locus for cleft lip with or without a cleft palate. Nat. Commun. 6:6414 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7414 (2015).

References

Mangold, E., Ludwig, K. U. & Nothen, M. M. Breakthroughs in the genetics of orofacial clefting. Trends Mol. Med. 17, 725–733 (2011) .

Dixon, M. J., Marazita, M. L., Beaty, T. H. & Murray, J. C. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 167–178 (2011) .

Christensen, K. & Fogh-Andersen, P. Cleft lip (+/− cleft palate) in Danish twins, 1970-1990. Am. J. Med. Genet. 47, 910–916 (1993) .

Sivertsen, A. et al. Familial risk of oral clefts by morphological type and severity: population based cohort study of first degree relatives. BMJ 336, 432–434 (2008) .

Grosen, D. et al. Recurrence risk for offspring of twins discordant for oral cleft: a population-based cohort study of the Danish 1936-2004 cleft twin cohort. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 152A, 2468–2474 (2010) .

Rahimov, F. et al. Disruption of an AP-2alpha binding site in an IRF6 enhancer is associated with cleft lip. Nat. Genet. 40, 1341–1347 (2008) .

Zucchero, T. M. et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. New Engl. J. Med. 351, 769–780 (2004) .

Birnbaum, S. et al. Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24. Nat. Genet. 41, 473–477 (2009) .

Mangold, E. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Nat. Genet. 42, 24–26 (2010) .

Beaty, T. H. et al. A genome-wide association study of cleft lip with and without cleft palate identifies risk variants near MAFB and ABCA4. Nat. Genet. 42, 525–529 (2010) .

Beaty, T. H. et al. Confirming genes influencing risk to cleft lip with/without cleft palate in a case-parent trio study. Hum. Genet. 132, 771–781 (2013) .

Ludwig, K. U. et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate identify six new risk loci. Nat. Genet. 44, 968–971 (2012) .

Yao, T. P. et al. Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300. Cell 93, 361–372 (1998) .

Tanaka, Y. et al. Extensive brain hemorrhage and embryonic lethality in a mouse null mutant of CREB-binding protein. Mech. Dev. 95, 133–145 (2000) .

Lai, A. H. et al. A submicroscopic deletion involving part of the CREBBP gene detected by array-CGH in a patient with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Gene 499, 182–185 (2012) .

Mattina, T. et al. Interstitial 16p13.3 microduplication: case report and critical review of genotype-phenotype correlation. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 55, 747–752 (2012) .

Tajir, M. et al. Germline mosaicism in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Gene 518, 476–478 (2013) .

Petrij, F. et al. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome caused by mutations in the transcriptional co-activator CBP. Nature 376, 348–351 (1995) .

Van Belzen, M., Bartsch, O., Lacombe, D., Peters, D. J. & Hennekam, R. C. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (CREBBP, EP300). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 118–120 (2011) .

Kim, S. R. et al. Cryptic microdeletion of the CREBBP gene from t(1;16) (p36.2;p13.3) as a novel genetic defect causing Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 43, 450–456 (2013) .

Hennekam, R. C. & Van Doorne, J. M. Oral aspects of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Suppl. 6, 42–47 (1990) .

Liu, G. et al. Netrin requires focal adhesion kinase and Src family kinases for axon outgrowth and attraction. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1222–1232 (2004) .

Li, W. et al. Activation of FAK and Src are receptor-proximal events required for netrin signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1213–1221 (2004) .

Ren, X. R. et al. Focal adhesion kinase in netrin-1 signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1204–1212 (2004) .

Masuda, T., Yaginuma, H., Sakuma, C. & Ono, K. Netrin-1 signaling for sensory axons: Involvement in sensory axonal development and regeneration. Cell Adh. Migr. 3, 171–173 (2009) .

Hallonet, M., Hollemann, T., Pieler, T. & Gruss, P. Vax1, a novel homeobox-containing gene, directs development of the basal forebrain and visual system. Genes Dev. 13, 3106–3114 (1999) .

Nasser, E. et al. Resequencing of VAX1 in patients with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 94, 925–933 (2012) .

Uslu, V. V. et al. Long-range enhancers regulating Myc expression are required for normal facial morphogenesis. Nat. Genet. 46, 753–758 (2014) .

Hu, Z. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies two new lung cancer susceptibility loci at 13q12.12 and 22q12.2 in Han Chinese. Nat. Genet. 43, 792–796 (2011) .

Southam, L. et al. The effect of genome-wide association scan quality control on imputation outcome for common variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 610–614 (2011) .

Coetzee, S. G., Rhie, S. K., Berman, B. P., Coetzee, G. A. & Noushmehr, H. FunciSNP: an R/bioconductor tool integrating functional non-coding data sets with genetic association studies to identify candidate regulatory SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e139 (2012) .

Andersson, R. et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature 507, 455–461 (2014) .

Rada-Iglesias, A. et al. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature 470, 279–283 (2011) .

Kobayashi, G. S. et al. Susceptibility to DNA damage as a molecular mechanism for non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. PLoS ONE 8, e65677 (2013) .

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007) .

Price, A. L. et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 38, 904–909 (2006) .

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis Springer (2009) Preprint at http://had.co.nz/ggplot2/book.

Pruim, R. J. et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 26, 2336–2337 (2010) .

Shi, M. et al. Genome wide study of maternal and parent-of-origin effects on the etiology of orofacial clefts. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 158 A, 784–794 (2012) .

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the China National High-Tech Research and Development Program Grant (2012AA020101) and partly funded by the National Key Basic Research Program Grant (2012CB720703), the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81230022), the Priority Academic Program of Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD 2014-37), the Priority Academic Program for the Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (JX10331801) and partly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81160131). We thank all of the study subjects, research staff and students who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y., L.W., H.S., J.C. and B.S. directed the study, obtained financial support and were responsible for the study design, interpretation of results and manuscript writing. Y.S., Y.H. and A.Y. performed overall project management with Y.P. and Y.W., performed statistical analyses with C.W. and H.M. and drafted the initial manuscript. Y.D., Z.H., L.X. and Y.J. directed each participating study and jointly organized this study. G.W., M.W., M.J. and F.L. were responsible for sample processing and managed the genotyping data. J.M., Z.Z. and Y.L. were responsible for subject recruitment and sample preparation of Huaxi and Ningxia samples. J.Q.M., W.Z., H.J. and L.M. were responsible for subject recruitment and sample preparation of Nanjing samples. X.Z. and Q.H. were responsible for subject recruitment and sample preparation of Guangzhou samples. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-6 and Supplementary Tables 1-9 (PDF 1475 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Huang, Y., Yin, A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new susceptibility locus for cleft lip with or without a cleft palate. Nat Commun 6, 6414 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7414

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7414

This article is cited by

-

Genetic association and functional validation of ZFP36L2 in non-syndromic orofacial cleft subtypes

Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Identification of putative regulatory single-nucleotide variants in NTN1 gene associated with NSCL/P

Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Chromatin conformation of human oral epithelium can identify orofacial cleft missing functional variants

International Journal of Oral Science (2022)

-

Allele-specific transcription factor binding in a cellular model of orofacial clefting

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Association of genetic polymorphisms of VAX1, MAFB, and NTN1 with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Chinese population

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.