Abstract

Photoswitchable molecules and nanoparticles constitute superior biosensors for a wide range of industrial, research and biomedical applications. Rendered reversible by spontaneous or deterministic means, such probes facilitate many of the techniques in fluorescence microscopy that surpass the optical resolution dictated by diffraction. Here we have devised a family of photoswitchable quantum dots (psQDs) in which the semiconductor core functions as a fluorescence donor in Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), and multiple photochromic diheteroarylethene groups function as acceptors upon activation by ultraviolet light. The QDs were coated with a polymer bearing photochromic groups attached via linkers of different length. Despite the resulting nominal differences in donor–acceptor separation and anticipated FRET efficiencies, the maximum quenching of all psQD preparations was 38±2%. This result was attributable to the large ultraviolet absorption cross-section of the QDs, leading to preferential cycloreversion of photochromic groups situated closer to the nanoparticle surface and/or with a more favourable orientation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photochromic Förster resonance energy transfer (pcFRET) is a versatile means for creating photomodulatable fluorescent systems. Using selected irradiation wavelengths a photochrome is reversibly converted between a non-acceptor isomer (with a small FRET overlap integral) and an acceptor isomer (with a large FRET overlap integral)1. In the latter case, the fluorescence of the donor is quenched by FRET and the conventional FRET formalism can be applied to the donor (D) and acceptor (A) pair. This concept has been widely applied in different areas such as optical data storage2, sensors3 and fluorescence microscopy4. With the aim of developing new probes for biosensing, our group and others have implemented pcFRET with nanoparticles, particularly quantum dots (QDs)5,6,7.

The multiple advantages of QDs as fluorescent probes—broad excitation, narrow emission, extreme photostability and high brightness—account for their widespread application as biosensors8. In many instances, the QDs function as energy donors in FRET, exhibiting both specific advantages and disadvantages9. QDs can be designed with high quantum yields and long-lived excited-state lifetimes, rendering them efficient as FRET donors9. A second characteristic of QDs is their relatively large size (>3 nm in diameter) compared with traditional organic dyes4. This feature potentiates the interaction of QD donors with multiple FRET acceptors, albeit at the price of greater complexity and heterogeneity10. The size of QDs also imposes a lower limit on the proximity of a potential acceptor to the emission dipole, generally represented as a point centred in the nanoparticle core. The Förster parameter (R0), the distance at which a given D–A pair exhibits 50% FRET efficiency, is usually in the single-digit nm range, compared with the radii of derivatized QDs that often exceed 10 nm. Nonetheless, due to the large effective Stokes shift resulting from the broad excitation band of QDs, they are optimal donors for measurements based on sensitized emission; that is, a convenient wavelength can generally be found that minimizes the direct excitation of the acceptor11. QDs do not constitute perfect point dipoles12, are often aspherical and surface charges can affect the FRET efficiency9. The influence of these variations and other limitations of the conventional FRET formalism13 are unpredictable yet generally minor, such that most QD FRET systems can and are described adequately by the classical treatments and equations9,14.

In this report, we feature a family of pcFRET constructs in which the D–A distance (rDA) was varied systematically, with intriguing, unexpected structural and functional consequences. In spite of pronounced differences in individual FRET efficiencies, the end-point ultraviolet-photomodulation of psQD fluorescence was an invariant 38±2%. We attribute this result to FRET-induced cycloreversion, functioning so as to compensate distance–orientation variations by adjustment of the steady-state distribution of acceptor groups.

Results

Design of psQD nanoparticles with photochromic acceptors

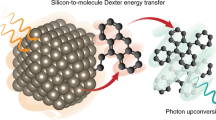

The psQDs consisted of a QD FRET donor and a cap of multiple photochromic (PC) diheteroarylethene FRET acceptors attached to an amphiphilic comb-like polymer via linkers of variable length (Fig. 1a). The QDs were commercially available CdSe/CdS/ZnS core–shell–shell nanoparticles15, and the polymer was based on a commercially available backbone, poly(isobutylene-alt-maleic anhydride) (PMA), which allows nucleophilic modification of the anhydride groups. Previous publications from our laboratory have shown that such a system constitutes a photoswitchable nanoparticle, denoted as psQD, that can be utilized in aqueous environments16,17. The particular nanoarchitecture and photophysical properties of the new psQDs resulted in a geometric arrangement with ‘self-regulating’ FRET properties.

(a) Diheteroarylethenes utilized to synthesize photochromic amphiphilic comb-like polymers. (b) Schematic of photoswitchable quantum dots and their quenching due to pcFRET. Exposure to ultraviolet light leads to cyclization, manifested by a new absorption band in the visible, which is reversed by irradiation at that wavelength. Adapted, with permission, from ref. 16. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society. (c) Extended linkers place the PC acceptor closer to the QD surface, thereby reducing rDA.

The PC moiety exists as two thermally stable isomers interchangeable by selective illumination (Fig. 1b). The open (non-cyclized, non-acceptor) isomer (oPC) has two conformations, parallel and antiparallel, in dynamic equilibrium; only the antiparallel can photocyclize18. The closed (acceptor) isomer (cPC) is formed upon ultraviolet irradiation of the oPC form. The conversion is incomplete because the cPC form also absorbs ultraviolet light and undergoes cycloreversion. Thus, sustained exposure to ultraviolet light leads to the attainment of a photostationary state (PS), defined by a maximal fractional conversion to cPC, αPS, which depends on the wavelength of the ultraviolet source (but not its irradiance, which only affects the kinetics of photoconversion) as well as on the local molecular microenvironment. The conversion of the isolated or polymer-associated PC selected for these studies was determined previously for the reference condition of irradiation at 340 nm in a non-polar solvent. The value obtained, αPS,0=0.22, constitutes an absolute, upper limit for the system in the absence of external perturbations16. In contrast, cycloreversion induced by exposure to light in the characteristic cPC absorption band at 550 nm is quantitative, that is, leading to 100% oPC, inasmuch as this isomer does not absorb in the visible (Vis) range. The diheteroarylethene photochromes do not undergo spontaneous thermal conversion in either direction. Thus, all combinations of oPC and cPC can be regarded as stationary in the sense of being stable in the absence of illumination.

psQD preparation and characterization

The first-generation psQDs underwent multiple cycles of photoswitching with minimal fatigue (degradation)16. The modulation of fluorescence did not exceed 40%; addition of a second non-PC acceptor boosted the value to 50%17. In classical FRET systems, the quenching of the donor can be increased by reducing rDA, and we sought to exploit this condition to enhance the QD quenching. A series of photochromic amphiphilic comb-like polymers were synthesized with pendant PC molecules differing only in the length of the linker (Fig. 1; Table 1; Methods; Supplementary Methods). On the basis of our previous studies of such systems, it was anticipated that the longer linkers would place the PCs closer to the QD surface, thereby lowering rDA16,17. All the prepared polymers had comparable PC concentrations, with 4.5–8% of the polymer chain monomers modified by the PC and the majority of the remaining monomers coupled to alkyl chains19.

An experiment was designed to determine PC, the total number of PCs per psQD nanoparticle, for the various preparations. The characterized psQD samples were precipitated by acidification and centrifuged, after which the pellet was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF), a solvent with which both the polymer cap and the QD interact preferentially such that the polymer exists as a freely draining dynamic chain20. Under these conditions the polymer-bound PC achieved its natural ultraviolet-induced PS (αPS,0=0.22; Supplementary Fig. 1), enabling the calculation of PC (Table 1). A decrease in packing efficiency had been anticipated for the polymers with greater backbone modification20, PMA 8PCaoc 75C12 serving as the extreme example. In fact, polymers containing >10% of bulky modifications such as PCs are unable to coat nanoparticles.

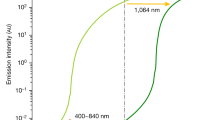

The rates and extents of photoconversion of oPC to cPC and the corresponding quenching of the QD emissions were monitored by both ultraviolet/Vis absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy following successive pulses of low-intensity ultraviolet (340±10 nm, 1.0 mW cm−2) or Vis (545±10 nm, 6.2 or 3.7 mW cm−2) irradiation (Fig. 2). The samples were utilized after being subjected to multiple photoconversion cycles to minimize the effect of the inherent, initial photobrightening generally observed with commercial QDs.

(a) Absorbance spectra of psQD PCalaNH2. (b) Fluorescence spectra of psQD PCalaNH2. (c) Fluorescence decay of psQD PCalaNH2, excited at 320 nm; emission collected at 550 nm. (d) Evolution of cPC/QD=cPC as a function of ultraviolet (1.0 mW cm−2) irradiation time. Solid lines: fits to a monoexponential decay function. (e) Quenching of QD fluorescence as a function of ultraviolet (1.0 mW cm−2) irradiation time. (f) Quenching of QD fluorescence as a function of cPC/QD. The fits to the data in d–f based on equation (2) are given in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2. Error bars correspond to measurement uncertainty and error propagation thereof.

The formation of cPC up to the attainment of the PS was monitored by ΔA540 (Fig. 2a). This process was accompanied by a pronounced quenching of the QD emission, manifested in both steady-state (Fig. 2b) and time-resolved (fluorescence decay) (Fig. 2c) measurements. However, whereas the dependence of photoconversion (cPC/QD) on the total irradiation time was close to monoexponential (Fig. 2d), the QD quenching was biphasic, with an initial rapid increase (of quenching) and a slower progression to a steady-state plateau value (Fig. 2e). This feature was common to all the psQDs, although the parametric plot (quench[t] versus cPC[t], Fig. 2f) split the five preparations into two main groups, one of which corresponded to the shorter linkers (0, 2 carbons) and the second to the longer linkers (6–12 carbons). A striking finding was that in spite of the kinetic differences, the maximum quenching in the PS, 38±2%, was independent of the linker length. The mean QD fluorescence lifetimes changed accordingly (Supplementary Table 1). The PS also demonstrated a marked decrease in αPS (from 0.19 to 0.07), which correlated with the increase in PC linker length (Table 2), in accordance with the expectation that the D–A separation would decrease for longer linkers, thereby favouring FRET. The decrease in αPS was not due solely to differences in coating efficiency, inasmuch as the values of PC did not correlate with the relative changes in αPS.

To rationalize the above observations, we invoked for each psQD preparation: (1) a degree of heterogeneity in the PC groups and the corresponding cPC populations generated by ultraviolet irradiation, and (2) a mechanism by which FRET-induced cycloreversion compensates and thus buffers distance–orientation variations. In this manner, FRET functions as a virtual photoselection principle establishing the steady-state distribution of cPC. These concepts are developed quantitatively in the following sections. We note that enhanced backconversion of cPC has been achieved with plasmonic enhancement from gold nanoparticles and shown to be dependent on the distance from the nanoparticle surface21,22.

pcFRET mechanism in psQDs

We have dealt previously16,17 with the operation of pcFRET in coupled systems of multiple photochrome acceptors assembled about a central QD donor; pcFRET dyads have been investigated by others23,24. The interplay between the photochromic acceptor and QD donor manifolds is illustrated in Fig. 3.

For simplicity only a single PC moiety is shown. In psQDs, multiple PCs are operative, each characterized by a given resonance energy transfer rate kt, depending on location and orientation relative to the QD core. Photocylization (koc) and photoreversal (kco) originate from electronic excited states (oPC* and cPC*, respectively); these quantities differ formally (in definition) from the rate constants denoted with the same symbols elsewhere in the text. QD decay is by emission (kf), non-radiative pathway(s) (knr) and FRET (kt).

The unique feature of pcFRET is the additional mechanism for inducing backconversion (cPC→oPC) via the QD donor. Many other systems incorporate QD donors and an array of centrosymmetric acceptors with presumably invariant transfer cross-sections25. In contrast, the transfer efficiency and acceptor distribution in the psQD pcFRET system varies continuously during the photochromic transitions. Thus, αPS depends on the wavelength of the photoconversion light sources in the near-ultraviolet, and the capacity of the QD donor to absorb light in the same region and transfer energy. For a system defined by specific geometric D–A relationships (separation, orientation), the evolution during the kinetic phase of the oPC–cPC interconversion reaction (Fig. 2d) is described by the following differential equation for the time-dependent number of closed form PCs per QD, cPC[t].

The first and second terms in equation (1) correspond to the light-dependent cyclization and ring-opening reactions, respectively, and the third term to FRET-induced ring opening; E[t] is the time-dependent transfer efficiency from the QD donor. The three kex coefficients are the rate constants for direct excitation (by light) of the oPC form, the cPC form and the QD, respectively; they are given numerically by the product of the respective absorption cross-sections and the irradiances, and thus vary with wavelength. Φoc and Φco are the quantum yields for ring closure and ring opening, respectively; Φoc includes the fraction (~0.60; Supplementary Methods) of the antiparallel conformation in the oPC population. kt[t]is the time-dependent rate constant for QD→cPC FRET, given by the product of PC[t], the parameter, γ, defined as the 6th power of the ratio of the Förster transfer constant R0 and the D–A separation, rDA; and the FRET-unperturbed QD excited-state decay rate kd,0.  is factored explicitly into the term,

is factored explicitly into the term,  (lacking κ2) with κ2 as a coefficient to accommodate molecular species varying independently in both orientation and D–A separation, while maintaining the same value of γ. Thus,

(lacking κ2) with κ2 as a coefficient to accommodate molecular species varying independently in both orientation and D–A separation, while maintaining the same value of γ. Thus,  , where J is the D–A overlap integral, n the refractive index of the medium in which transfer occurs (in our case identified with the polymer coat) and Q is the donor (QD) quantum yield (0.2) in the absence of FRET. The invariant

, where J is the D–A overlap integral, n the refractive index of the medium in which transfer occurs (in our case identified with the polymer coat) and Q is the donor (QD) quantum yield (0.2) in the absence of FRET. The invariant  computed for FRET occurring within the polymer cap of the psQD systems was 4.16 nm6 (Supplementary Note 1). The issue of distance–orientation coupling is treated in further detail below. Equation (1) incorporates the assumption that in the presence of a single donor (the QD) and i identical acceptors, each with FRET rate kt, the net transfer rate, kt,tot, is given by i · kt (ref. 26). By definition, the FRET efficiency E[t] is equivalent to the fractional quenching of the QD donor.

computed for FRET occurring within the polymer cap of the psQD systems was 4.16 nm6 (Supplementary Note 1). The issue of distance–orientation coupling is treated in further detail below. Equation (1) incorporates the assumption that in the presence of a single donor (the QD) and i identical acceptors, each with FRET rate kt, the net transfer rate, kt,tot, is given by i · kt (ref. 26). By definition, the FRET efficiency E[t] is equivalent to the fractional quenching of the QD donor.

The solution to equation (1) yields the kinetic course of the reaction initiated by exposure to ultraviolet or Vis light and the PS established at its conclusion. A number of interesting features revealed by simulations based on equation (1) are featured in Supplementary Note 2; Supplementary Fig. 3. However, the unimodal (single population) model fails to reproduce the very different time courses of quenching and photoconversion exhibited by the psQDs, such that a degree of population heterogeneity with respect to γ (and thus in rDA and/or κ2) must be invoked. That is, the rapid initial quenching (Fig. 2e) implies that the (sub)populations of PC groups with larger values of γ photoconvert faster, albeit to a reduced extent. Both of these circumstances are attributable to larger values of k3E[t], which lead to an increase in  and to a corresponding decrease in αPS.

and to a corresponding decrease in αPS.

Explicit consideration of the static acceptor condition

Under the assumption of an invariable chemical microenvironment of the PC in the various preparations, the variation in the aliphatic linker length should not affect the inherent photoconversion mechanism. That is, the different psQDs could be considered as FRET systems with common parameters except for the D–A separation rDA. However, during the course of this study it became apparent that another key FRET factor, the orientational distribution of photoconverted cPC acceptors (represented via κ2, the D–A dipole–dipole orientation factor), must be considered explicitly in quantitative treatments. We have previously utilized the value of 2/3 for κ2 generally assumed for dynamic, rotationally isotropic systems17. However, because QDs and PC groups are deemed to be immobile on the photophysical time scale (ns), the appropriate FRET formalism is that applicable to the ‘static orientational regime’ in which case it is necessary to consider κ2 separately from the other parameters constituting the Förster constant  (see equation (1)). We have applied concepts and results from seminal publications of van de Meer and Vogel27,28,29,30 to the analysis of the psQDs. It was apparent that the variation in αPS, and thus γ, was incompatible with a constant E, in view of the expression given by Vogel et al.30 for the random, isotropic case:

(see equation (1)). We have applied concepts and results from seminal publications of van de Meer and Vogel27,28,29,30 to the analysis of the psQDs. It was apparent that the variation in αPS, and thus γ, was incompatible with a constant E, in view of the expression given by Vogel et al.30 for the random, isotropic case:  .

.

QD-based systems differ inherently from the conventional D–A pairs based on organic molecules in that each successive excitation of the semiconductor core of the QD generates an emission dipole that is oriented randomly with respect to any given, individual acceptor. As a consequence, the applicable value of κ2 requires azimuthal and polar averaging using distinct orientations of the acceptor absorption dipole with respect to the D–A separation vector, R, which is colinear with a corresponding particular radius (assuming spherical centrosymmetry) of the QD. Our computations based on these notions indicate that the mean orientation factor, ‹κ2›, can vary between 8/(3π)=0.85 and 2/(3π)=0.21, respectively, for an acceptor transition moment oriented colinear with or perpendicular to R (Supplementary Note 1). One should note that individual κ2 values can lie between 0 and 4 (see Fig. 4.5 in ref. 28), while  in the psQD systems reported here can probably vary by a factor of ~101.5–2.5. Inclusion of a particular PC group in an acceptor (sub)population defined by a given operational value γi requires (only) that it satisfy the condition

in the psQD systems reported here can probably vary by a factor of ~101.5–2.5. Inclusion of a particular PC group in an acceptor (sub)population defined by a given operational value γi requires (only) that it satisfy the condition  . We stress that whereas the γi are representative of the FRET capability of specific subpopulations of acceptors within a psQD, and are thus invariant once defined by the fits, the mean value ‹γ› for the psQD as a whole is dependent on the degree of photoconversion.

. We stress that whereas the γi are representative of the FRET capability of specific subpopulations of acceptors within a psQD, and are thus invariant once defined by the fits, the mean value ‹γ› for the psQD as a whole is dependent on the degree of photoconversion.

Photoconversion heterogeneity

We now return to the observed deviation of the QD-quenching functions from monoexponential behaviour, with large increases at short irradiation times (low cPC values) and an asymptotic behaviour as the PS is approached (Fig. 2e). One attributes such behaviour in conventional QD FRET systems to inherent, static heterogeneity with greater relative quenching at low valencies31. In the case of the psQDs, it is necessary to invoke not only a static but also a dynamic (time dependent) heterogeneity in population mean FRET efficiencies, such that the final distribution of cPC groups is incongruous with that of the total PC population but biased systematically to lower values of ‹γ›, that is, greater D–A separations and/or lower ‹κ2›.

We have previously considered a simple dual-population acceptor model for psQD constructs17. In the present study, we improved data fitting by invoking for each psQD species three PC subpopulations, i=1–3 (this choice is discussed below), defined by the corresponding FRET transfer rates from the QD donor to the cPC acceptor form (kt,i), expressed via the respective values of γi. The subpopulations generated by the fitting procedure were renumbered in order of increasing values of γi. The total numbers of the PC groups (PCi) of the subpopulations were freely adjustable, although subject to the requirement that they add up to the predetermined experimental PC values within their given statistical range. As noted in the previous section, a given value of γi can arise from very different combinations of κ2 and rDA. In the differential equation (2), the underlying principle of equation (1) is extended in that the individual FRET efficiencies are coupled, yielding the following time-dependent relationships for Ei[t], E[t] (the global transfer efficiency), and ‹γ›[t], the time-dependent mean global value of γ.

An important assumption underlying equation (2) is that with i distinct subpopulations of acceptors, ni in number,  . Since there is only a single donor in an individual psQD, the various decay paths mediated by FRET are competitive. That is, the instantaneous quenching produced by the ith acceptor subpopulation, Ei[t], is a function of the other values Ek≠i[t], because the energy transfer probabilities are additive. At equilibrium, the most efficient paths (largest cPCPS,i·γi) lead to the lowest degree of photoconversion, that is, value of αPS,i. Furthermore, the net transfer efficiency, EPS, and thus QD quenching, in the PS, is a function of all the PC and γ values (equation (3)). Equation (3) is valid for i=1–3 subpopulations (via selection of PCi) and is of general utility for parametric modelling of psQDs and other related systems based on pcFRET.

. Since there is only a single donor in an individual psQD, the various decay paths mediated by FRET are competitive. That is, the instantaneous quenching produced by the ith acceptor subpopulation, Ei[t], is a function of the other values Ek≠i[t], because the energy transfer probabilities are additive. At equilibrium, the most efficient paths (largest cPCPS,i·γi) lead to the lowest degree of photoconversion, that is, value of αPS,i. Furthermore, the net transfer efficiency, EPS, and thus QD quenching, in the PS, is a function of all the PC and γ values (equation (3)). Equation (3) is valid for i=1–3 subpopulations (via selection of PCi) and is of general utility for parametric modelling of psQDs and other related systems based on pcFRET.

where

The cPC[t] and quench[t] data for the five psQD classes (Fig. 2d–f) were fit by equations (1) and (2) using the ParametricNDSolve and NonlinearModelFit procedures of Mathematica (Wolfram Research), with PCi, γi, and k1, k2 and k3 as the fitting variables for each psQD. The parameters were to a degree degenerate since PC is constrained (the values were allowed to vary within the range given by measured mean±s.d.) and with αPS,0=0.22, the value of k2/k1 was fixed to 3.545. The assumption was that the PCs were identical in photophysical properties, regardless of their position within the polymer cap. The detailed fitting protocols, simulations and results are given in Supplementary Note 3. Selected fit parameters are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 4.

(a) αPS,i, subpopulations numbered in order of γi. (b) Corresponding normalized transfer rates of the acceptor subpopulations. Note that  (c) Temporal evolution of ‘FRET potency’, ‹γ›, as a function of ultraviolet (irradiance 1.0 mW cm−2) irradiation time. (d) Derived time-dependent apparent D–A separation rDA as a function of ultraviolet (irradiance 1.0 mW cm−2) exposure time.

(c) Temporal evolution of ‘FRET potency’, ‹γ›, as a function of ultraviolet (irradiance 1.0 mW cm−2) irradiation time. (d) Derived time-dependent apparent D–A separation rDA as a function of ultraviolet (irradiance 1.0 mW cm−2) exposure time.

The successful fitting procedures validate the choice of a discrete number of components to represent the heterogeneous population of PC groups in each class of psQDs. Exploration of other potential distribution functions, for example a truncated Gaussian, indicated that the derived global parameters such as ‹γ› were not contingent on the adoption of a particular model. Due to the 6th power dependence of γ on distance, three components with parameters freely selectable in the fitting procedure provided sufficient flexibility to account for the overall psQD performance. Fitting with a large number of subpopulations yielded parameters without statistical significance. The instantaneous value of the mean quantity ‹γ› is equal to the derivative of quench[t], that is, the fractional quenching per unit increment in cPC, and thus constitutes a measure of what we denote as ‘FRET potency’. Table 3 presents the values of both ‹γ›0 and ‹γ›PS, while the time courses from the initial to the PS state are shown in Fig. 4c.

The decrease in FRET protency during the time course of irradiation underlies the mechanism of energy transfer self-regulation in the psQDs. Qualitatively, it reflects the transition from the maximal achievable rate of photoconversion upon exposure to ultraviolet light, the ‘substrate’ being the PCs in the oPC form, to the maximal rate of FRET-induced cycloreversion in the PS, in which case the corresponding cPC ‘substrate’ concentration is maximal. In terms of the photoconversion reaction itself, the system shifts from being determined by k1 and k2 to being dominated by k1 and k3. An important implication is that one can exploit the very different properties of a given nanoparticle by judicious selection of the operational condition (see Discussion).

The values of ‹γ›0, representing the condition under which all PCs are in the oPC form, were quite different for the various psQDs, in accordance with the pcFRET theory. That is, the increase of ‹γ› correlated with greater linker length (smaller rDA), reflecting the anticipated closer proximity of the PC groups to the QD surface. For example, the PCaocNH2 linker provides a 10-fold higher FRET potency than PCmNH2, an important distinction for many applications of psQDs. The exemption was the class 5 psQD PCadoNH2 linker, which was longer than the alkyl chains of the QD ligands (TOPO, TOP and HDA). We conclude that the steric nonconformity forced the linker into a foldback configuration, thereby positioning the terminal PC group somewhere between the region corresponding to linker species 3 and 4.

Examination of the subpopulations defined in the fitting procedure leads to additional insights into the functional substructure of the psQD preparations. As in the case of the global parameters of the different psQDs, the values of αPS,i of the corresponding subpopulations were also inversely related to γi (Fig. 4a). This feature is also evident in Fig. 4b, featuring the FRET transfer rate, kt,i/kd,0=cPCPS,i·γi, of each subpopulation in the PS. The distribution of FRET transfer activity was biased towards the subpopulations with lower γi, thereby creating greater uniformity in the overall system.

Another key parameter that could be derived from the data was the mean donor–acceptor distance for each class of psQDs. Equation (4) provides an estimate of rDAbased on the mean global FRET parameter ‹γ›[t] at any point during the time course of photoconversion.

A midrange value of ‹κ2›=5/(3π)=0.53 and  were utilized to compute the initial and PS values of rDA (Table 3). The computed distances were compatible with the radius of the QD (3 nm) as well as the assembled psQD in solution, previously determined as 7 nm (ref. 17). According to these estimates, the ‘furthermost’ PCs, located on the outer edge of the coated psQD, were in PCmNH2 while those of PCaocNH2 were closest to the QD surface. The absolute and relative changes, as well as the rates characterizing the time dependence of rDA[t], differed between the psQD preparations in a manner compatible with considerations presented earlier and the clustering evident in Fig. 2f. However, we note that the shifts in the calculated distances between rDA,0 and rDA,PS within the psQD preparations were in the range of 1.2–2.1 nm, values generally larger than those encompassed by the linkers (0.0–1.6 nm). We rationalize this finding by invoking distance-coupled orientational selection according to which ‹κ2› also varied in time.

were utilized to compute the initial and PS values of rDA (Table 3). The computed distances were compatible with the radius of the QD (3 nm) as well as the assembled psQD in solution, previously determined as 7 nm (ref. 17). According to these estimates, the ‘furthermost’ PCs, located on the outer edge of the coated psQD, were in PCmNH2 while those of PCaocNH2 were closest to the QD surface. The absolute and relative changes, as well as the rates characterizing the time dependence of rDA[t], differed between the psQD preparations in a manner compatible with considerations presented earlier and the clustering evident in Fig. 2f. However, we note that the shifts in the calculated distances between rDA,0 and rDA,PS within the psQD preparations were in the range of 1.2–2.1 nm, values generally larger than those encompassed by the linkers (0.0–1.6 nm). We rationalize this finding by invoking distance-coupled orientational selection according to which ‹κ2› also varied in time.

The quantum yields of photochromism were also determined from the various fit parameters, including those derived from the kinetics of cycloreversion induced by irradiation at 540 nm. Values of 0.3±0.1 (s.d.) were obtained for both cyclization (including the factor for the antiparallel oPC fraction) and cycloreversion. These quantum yield estimates are higher than those we reported previously16.

Analysis of other photoswitchable semiconductor nanocrystals

We have studied structural and compositional variables of other photoswitchable nanoparticles to test the validity of the model proposed for psQDs.

A photochromic polymer (PMA 8PCaoc 75C12) was coated onto a batch of expired (over a year past expiration date) QDs, which had lost >80% of their initial luminescence (Supplementary Fig. 2). It is unclear whether the effect was homogenous or heterogeneous in the population of nanoparticles; however, this consideration does not affect the interpretation of the results. It was assumed that the QD parameters other than the decreased quantum yield were unchanged. For example, coating the expired QDs occurred readily, as with the original QDs, implying that they had neither aggregated nor shed excess surface ligands. The expired sample had a faster cyclization rate  (0.037±0.001 s−1) and a higher αPS (0.17 compared with 0.07; Table 2) than the psQDs with higher quantum yields (Supplementary Fig. 2), a result supporting the attribution of a dominant influence of QD-mediated pcFRET (k3, E) on the cycloreversion of cPC.

(0.037±0.001 s−1) and a higher αPS (0.17 compared with 0.07; Table 2) than the psQDs with higher quantum yields (Supplementary Fig. 2), a result supporting the attribution of a dominant influence of QD-mediated pcFRET (k3, E) on the cycloreversion of cPC.

Another fluorescent semiconductor nanocrystal (Series A plus 560 nm, CAN GmbH, Hamburg), elongated CdSe/CdS core–shell nanorods (24 nm length, 4.6 nm diameter) with higher extinction coefficients (ε340 5,500; ε400 4,000; ε540 227 mM−1 cm−1), provided an additional test for the proposed psQD model. The quantum rods (QRs) had an emission spectrum similar to that of the original QDs (Figs 2b and 5b). They were coated and purified in a similar manner as the psQDs, eluting earlier from the size-exclusion chromatography column due to their larger size. The resultant photoswitchable nanorods (psQR) differed physically from the psQDs in having a rod shape and a sixfold increase in surface area. The pcFRET properties were also different: PC=125±20, R0=6.0 nm (utilizing a 2/3 estimation for ‹κ2› and a higher quantum yield), and an emission source no longer representable as a single point dipole at the crystal centre. The polymer coating of the psQR necessarily lacks radial symmetry such that detailed evaluations of κ2 are difficult. However, the predictions of equations (1)–(3), , were fulfilled in that the psQR showed lower values of αPS (PCalaNH2, 0.10 to PCaocNH2, 0.02) and corresponding EPS (0.25 to 0.15). As an example, the psQR prepared with PCadoNH2 polymer had αPS,0=0.04 and EPS=0.15, implying a 19-fold increase in k3/k1, a value close to the 16-fold larger extinction coefficient of the QR.

Pre-irradiated polymer (ultraviolet, α=0.22; visible, α=0). Photostationary (ultraviolet) psQR, αPS=0.10. (a) Absorbance spectra. (b) Fluorescence spectra, excitation at 400 nm. (c) Normalized fluorescence of two psQR samples that had been previously irradiated into the PS state (αPS=0.22) and then exposed to pulses of ultraviolet (filled symbols) or visible (empty symbols) light. The shaded region indicates the time after the change in irradiation wavelength. (d) Fluorescence of a psQR sample undergoing cycles of irradiation demonstrating that the pre-irradiated state (α=0.22) with almost complete quenching could not be restored. Irradiation times, 180 s.

Since backconversion due to FRET limited the quenching of the QD, a system was designed in which the nanoparticle was coated with a pre-irradiated photochromic polymer. This strategy shifted αPS (and thus EPS) to larger values than were achievable in the ultraviolet-induced PS state of the psQDs. The QRs were selected for this experiment since they exhibited increased stability, less photobrightening and higher brightness than the QDs. Two psQR samples were prepared with the PMA 6PCala 75C12 polymer at the same time and under the same conditions, including protection from light (except red), to avoid photoconversion during purification. One sample was irradiated before coating so as to achieve αPS,0 (0.22) while the other had all PC groups in the open form, thus corresponding to α=0. After purification the fluorescence and absorbance of the samples were measured, and they were then exposed to pulses of either ultraviolet or Vis light (Fig. 5).

The psQR with α=0 exhibited the expected characteristics: ultraviolet irradiation led to a quenching of the psQR by 25±3% and Vis irradiation restored the fluorescence to the initial state. The sample exhibited photobrightening and served as a control, allowing for the normalization in Fig. 5b–d. The pre-irradiated, ( =0.22) psQR had an initial fluorescence of only 2–5% (95–98% quenching) and increased in intensity upon irradiation with either Vis or ultraviolet light. After restoring the open form with green-light irradiation, the 100% reference fluorescence of the QR was observed, but it was not possible to achieve complete quenching during subsequent cycling (Fig. 5d). Ultraviolet irradiation also increased the fluorescence intensity of the pre-irradiated sample, but only until the αPS value was obtained, at which point Vis light was required to regenerate 100% fluorescence (Fig. 5c). Absorbance measurements and polymer-stripping experiments indicated that the maximum number of cPC was 17, and that α decreased from an intial value of 0.21 to 0.10 after exposure to light.

=0.22) psQR had an initial fluorescence of only 2–5% (95–98% quenching) and increased in intensity upon irradiation with either Vis or ultraviolet light. After restoring the open form with green-light irradiation, the 100% reference fluorescence of the QR was observed, but it was not possible to achieve complete quenching during subsequent cycling (Fig. 5d). Ultraviolet irradiation also increased the fluorescence intensity of the pre-irradiated sample, but only until the αPS value was obtained, at which point Vis light was required to regenerate 100% fluorescence (Fig. 5c). Absorbance measurements and polymer-stripping experiments indicated that the maximum number of cPC was 17, and that α decreased from an intial value of 0.21 to 0.10 after exposure to light.

By pre-irradiating the PC acceptors and then coating the QR, we succeeded in bypassing the self-regulation of the system imposed by FRET, thereby achieving a much higher fractional conversion to the cPC form, as well as exploiting the higher FRET potency of γ0 compared with ‹γ›PS. Upon cycling, this circumstance could no longer be achieved, such that quenching was finite. The pre-irradiation strategy allows the development of a completely photoactivatable QD probe inasmuch as the diheteroarylethenes lack thermal backconversion. This circumstance is similar to other caged fluorescence QDs presented in the literature, with which the destruction32 or release33,34 of the quencher decages the QD. Our system presents the additional advantages that the initial fluorescence increase can be realized with a broad range of excitation wavelengths <550 nm, and that upon dequenching the sample can still undergo photomodulation. The samples in Fig. 5 were measured 3 days after preparation, but others stored up to a month showed a similar response.

Discussion

A key finding of this study is that in the ultraviolet-induced PS the photomodulation of psQD by pcFRET is operationally distance independent. The ultraviolet light used to photocyclize the PC to the cPC form excites the QD, which transfers energy to a pre-existing cPC acceptor and drives it back to the oPC conformation. Photocyclization is unaffected by FRET, while cycloreversion is highly dependent on the FRET efficiency and cPC content. In the other PS achieved by exposure to Vis light, the PCs exist exclusively in the open, acceptor-incompetent form because photocyclization is excluded. Under this condition, the ‘FRET potency’, expressed as fractional QD quenching per extent of acceptor photoconversion, can be substantially accentuated by increasing linker length, that is, by ‘engineering (reducing)’ rDA. Thus, the psQD family members of this study differ under one condition but not the other.

The relative contribution of cycloreversion to the reaction under ultraviolet irradiation increases as α progresses from 0 (all PCs in the oPC form) to αPS in the PS state, due in part to the large discrepancy in extinction coefficients of the various molecular species at 340 nm (ε, mM−1 cm−1: QD, 342; oPC, 2.0; cPC, 9.1). Thus, in psQDs the single QD donor undergoes 2–4 more cycles of excitation per unit time than the entire ensemble of PC groups. FRET ‘photoselection’ can also be regarded as a means for using light to selectively nanoposition distinct chemical groups (in this case oPC and cPC) on the surface of a nanoparticle. That is, while the distribution of the PCs as a whole is determined by ground-state chemistry, that of the cPC subpopulation depends on photonic principles and photochemistry.

As FRET increases, the QD emits fewer photons (is more quenched), yet the content of cPC groups, that is, the operational acceptors, is also reduced. Quenching is independent of the D–A distance as long as the QD absorbance is considerably higher than that of the total oPC content at the irradiation wavelength. It follows that the development of novel FRET-based photomodulatable probes requires consideration of more than the D–A spectral overlap and rDA, inasmuch as the rate constants for the forward and reverse reactions at the conversion wavelength(s) affect the kinetics and extent of quenching in a complex manner.

Expanding the dynamic range (achieving greater quenching) in the psQD system requires larger values of αPS,0, and thus a reduction in k2/k1 [αPS,0=(1+k2/k1)−1] and/or in k3/k1. These aims can be achieved by optimizing (i) the choice of PC (greater oPC absorption cross-section, lower quantum yield of cycloreversion); (ii) nanoparticle composition, size and shape; and/or (iii) the ultraviolet photoconversion wavelength. Increasing PC, the ostensibly most obvious way to promote greater quenching, is limited by the finite amount of polymer that can bind irreversibly to the QD as well as by the necessity of maintaining PC modification of the polymer to <10% to ensure successful transfer of the the QD to an aqueous medium. We have demonstrated that capping with a pre-irradiated polymer can create virtually completely quenched QDs, which can serve as binary photoactivatable cellular probes. Numerous approaches for achieving spatial and as well as temporal super-reresolution can be considered on the basis of the principles applied in the existing psQD constructs.

Polymer modification and capping is extremely versatile in other ways. One can envision numerous extensions of the system featured in this report, for example, the use of other PC groups and modalities: PCs with a fluorescent cPC form35; chemically gated PCs36; invisible (blue-shifted cPC) PCs37; multicolour PCs38; and enantioselective photochromism39. The capabilities offered by other photonic strategies directed at the distinct ‘writing, reading, erasing’ functions of psQDs (or more generally photoswitchable nanoparticles) are extensive: simultaneous or alternating40 wavelengths for photoconversion and monitoring, which permit biasing the system at any desired PS-operating point; switching between low and high irradiance regimes to achieve saturation for enhancing/suppressing FRET41 and/or resolution42; multiphoton cycloreversion43; and lock-in detection for enhancing contrast and selectivity in microscopy44, thus exploiting the distinctive ‘FRET potencies’ achievable by engineering the polymer-linker cap. The latter feature constitutes a means for implementing a single-spectrum barcode.

Methods

Synthesis

The PC and photochromic comb-like polymers were synthesized as previously described in the literature20,45 (for details see Supplementary Methods).

psQD preparation

The psQD preparation was slightly modified from that reported in the literature19,46. The QDs (Series A CSS 540 nm QDs, CAN GmbH) were precipitated from the solvent by a procedure supplied by the manufacturer and resuspended in anhydrous CHCl3. A solution of the photochromic polymer was prepared in CHCl3 (~10 mg ml−1) and added to a QD or QR solution in a glass flask in a previously determined optimum proportion (1 mg polymer per ~900 pmol of the nanoparticle). The solution was mixed at 65 °C for 2 h, after which the solvent was slowly evaporated. The dry sample was resuspended in an excess of 50 mM SBB and stirred slowly overnight.

psQD purification

Sample purification was realized by filtration with 0.2-μm inorganic filters, after which the solutions were concentrated to ~1 μM using Amicon 100-kDa cutoff filters (Millipore) and a 50 mM Na-borate, pH 9.0 buffer. Injections of 20 or 50 μl (depending on concentration) were applied to a Superdex 200 analytical column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in an HPLC system with ultraviolet–Vis detection. Elution was with 50 mM Na-borate, pH 9, starting with a flow of 50 μl min−1 for 3 min and then 20 μl min−1. The average run time was 70 min. The QD fraction was collected in the 45-min range, while the QR fraction was collected at 42 min. In some cases a second injection was required to obtain the desired purity.

The relevant molar extinction coefficients (ε, mM−1 cm−1 at 340 nm) are: QD, 342; oPC, 2.0; cPC, 9.1. At 540 nm, ε (mM−1 cm−1) of cPC=17.5.

Polymer stripping

An aliquot of each psQD (150 μl) was acidified by addition of 1 N HCl (25 μl, final pH 2) and left to aggregate overnight at room temperature. The samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 r.p.m. for 4 min, obtaining a pellet. The supernatant was separated and the pellet was then dissolved in an equivalent volume of THF. The sample was allowed to settle for 2 h to eliminate scattering due to micelle formation, after which photoconversion of the polymer was measured as stated above.

Measurements

Measurements were carried out as reported previously16. A custom-built absorption/fluorescence spectrometer with built-in photoconversion capabilities was utilized for the expired QD and some of the pre-irradiated measurements35.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Díaz, S. A. et al. Photoswitchable semiconductor nanocrystals with self-regulating photochromic Förster resonance energy transfer acceptors. Nat. Commun. 6:6036 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7036 (2015).

References

Giordano, L., Jovin, T. M., Irie, M. & Jares-Erijman, E. A. Diheteroarylethenes as thermally stable photoswitchable acceptors in photochromic fluorescence resonance energy transfer (pcFRET). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 7481–7489 (2002).

Bianco, A., Perissinotto, S., Garbugli, M., Lanzani, G. & Bertarelli, C. Control of optical properties through photochromism: a promising approach to photonics. Laser Photon. Rev. 5, 711–736 (2011).

Zhang, J., Zou, Q. & Tian, H. Photochromic materials: more than meets the eye. Adv. Mater. 25, 378–399 (2013).

Jares-Erijman, E. A. & Jovin, T. M. FRET imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1387–1395 (2003).

Jares-Erijman, E., Giordano, L., Spagnuolo, C., Lidke, K. & Jovin, T. M. Imaging quantum dots switched on and off by photochromic fluorescence resonance energy transfer (pcFRET). Mol. Cryst. Liquid Cryst. 430, 257–265 (2005).

Wu, T., Boyer, J.-C., Barker, M., Wilson, D. & Branda, N. R. A “plug-and-play” method to prepare water-soluble photoresponsive encapsulated upconverting nanoparticles containing hydrophobic molecular switches. Chem. Mater. 25, 2495–2502 (2013).

Jung, H.-y., You, S., Lee, C., You, S. & Kim, Y. One-pot synthesis of monodispersed silica nanoparticles for diarylethene-based reversible fluorescence photoswitching in living cells. Chem. Commun. 49, 7528–7530 (2013).

Petryayeva, E., Algar, W. R. & Medintz, I. L. Quantum dots in bioanalysis: a review of applications across various platforms for fluorescence spectroscopy and imaging. Appl. Spectrosc. 67, 215–252 (2013).

Medintz, I. L. & Mattoussi, H. Quantum dot-based resonance energy transfer and its growing application in biology. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11, 17–45 (2009).

Algar, W. R., Kim, H., Medintz, I. L. & Hildebrandt, N. Emerging non-traditional Förster resonance energy transfer configurations with semiconductor quantum dots: Investigations and applications. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 263-264, 65–85 (2014).

Ishikawa-Ankerhold, H. C., Ankerhold, R. & Drummen, G. P. C. Advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques—FRAP, FLIP, FLAP, FRET and FLIM. Molecules 17, 4047–4132 (2012).

Chung, I. H., Shimizu, K. T. & Bawendi, M. G. Room temperature measurements of the 3D orientation of single CdSe quantum dots using polarization microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 405–408 (2003).

Beljonne, D., Curutchet, C., Scholes, G. D. & Silbey, R. J. Beyond Förster resonance energy transfer in biological and nanoscale systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6583–6599 (2009).

Hua, Z. et al. Energy transfer from a single semiconductor nanocrystal to dye molecules. ACS Nano 8, 7060–7066 (2014).

Talapin, D. V. et al. CdSe/CdS/ZnS and CdSe/ZnSe/ZnS core−shell−shell nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 18826–18831 (2004).

Díaz, S. A. et al. Photoswitchable water-soluble quantum dots: pcFRET based on amphiphilic photochromic polymer coating. ACS Nano 5, 2795–2805 (2011).

Díaz, S. A., Giordano, L., Jovin, T. M. & Jares-Erijman, E. A. Modulation of a photoswitchable dual-color quantum dot containing a photochromic FRET acceptor and an internal standard. Nano Lett. 12, 3537–3544 (2012).

Irie, M. Photochromism of diarylethene single molecules and single crystals. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 9, 1535–1542 (2010).

Fernández-Argüelles, M. T. et al. Synthesis and characterization of polymer-coated quantum dots with integrated acceptor dyes as FRET-based nanoprobes. Nano Lett. 7, 2613–2617 (2007).

Diaz, S. A., Giordano, L., Azcarate, J. C., Jovin, T. M. & Jares-Erijman, E. A. Quantum dots as templates for self-assembly of photoswitchable polymers: small, dual-color nanoparticles capable of facile photomodulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 3208–3217 (2013).

Nishi, H., Asahi, T. & Kobatake, S. Plasmonic enhancement of gold nanoparticles on photocycloreversion reaction of diarylethene derivatives depending on particle size, distance from the particle surface, and irradiation wavelength. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 4898–4905 (2012).

Ouhenia-Ouadahi, K. et al. Photochromic-fluorescent-plasmonic nanomaterials: Towards integrated three-component photoactive hybrid nanosystems. Chem. Commun. 50, 7299–7302 (2014).

Spangenberg, A. et al. Photoswitchable interactions between photochromic organic diarylethene and surface plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles in hybrid thin films. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 9670–9678 (2013).

Ouhenia-Ouadahi, K. et al. Fluorescence photoswitching and photoreversible two-way energy transfer in a photochrome-fluorophore dyad. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 11, 1705–1714 (2012).

Kim, H., Ng, C. Y. W. & Algar, W. R. Quantum dot-based multidonor concentric FRET system and its application to biosensing using an excitation ratio. Langmuir 30, 5676–5685 (2014).

Fabian, A. I., Rente, T., Szollosi, J., Matyus, L. & Jenei, A. Strength in numbers: effects of acceptor abundance on FRET efficiency. ChemPhysChem 11, 3713–3721 (2010).

van der Meer, B. W. Kappa-squared: from nuisance to new sense. Rev. Mol. Bioctechnol. 82, 181–196 (2002).

van der Meer, BW, van der Meer, DM & Vogel, SS. in:FRET—Förster Resonance Energy Transfer eds Medintz I, Hildebrandt N 63–104Wiley-VCH (2013).

Vogel, S. S., Nguyen, T. A., van der Meer, B. W. & Blank, P. S. The impact of heterogeneity and dark acceptor states on FRET: implications for using fluorescent protein donors and acceptors. PLoS ONE 7, e49593 (2012).

Vogel, S. S., van der Meer, B. W. & Blank, P. S. Estimating the distance separating fluorescent protein FRET pairs. Methods 66, 131–138 (2014).

Pons, T., Medintz, I. L., Wang, X., English, D. S. & Mattoussi, H. Solution-phase single quantum dot fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 15324–15331 (2006).

Tagliazucchi, M., Amin, V. A., Schneebeli, S. T., Stoddart, J. F. & Weiss, E. A. High-contrast photopatterning of photoluminescence within quantum dot films through degradation of a charge-transfer quencher. Adv. Mater. 24, 3617–3621 (2012).

Han, G., Mokari, T., Ajo-Franklin, C. & Cohen, B. E. Caged quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15811–15813 (2008).

Impellizzeri, S., McCaughan, B., Callan, J. F. & Raymo, F. M. Photoinduced enhancement in the luminescence of hydrophilic quantum dots coated with photocleavable ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2276–2283 (2012).

Gillanders, F., Giordano, L., Diaz, S. A., Jovin, T. M. & Jares-Erijman, E. Photoswitchable fluorescent diheteroarylethenes: substituent effects on photochromic and solvatochromic properties. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 13, 603–612 (2014).

Ohsumi, M., Fukaminato, T. & Irie, M. Chemical control of the photochromic reactivity of diarylethene derivatives. Chem. Commun. 3921–3923 (2005).

Fukaminato, T., Tanaka, M., Kuroki, L. & Irie, M. Invisible photochromism of diarylethene derivatives. Chem. Commun. 3924–3926 (2008).

Morimoto, M., Kobatake, S. & Irie, M. Multicolor photochromism of two- and three-component diarylethene crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11080–11087 (2003).

Yamamoto, S., Matsuda, K. & Irie, M. Absolute asymmetric photocyclization of a photochromic diarylethene derivative in single crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 1636–1639 (2003).

Lee, N.K. et al. Three-color alternating-laser excitation of single molecules: monitoring multiple interactions and distances. Biophys. J. 92, 303–312 (2007).

Beutler, M. et al. satFRET: estimation of Förster resonance energy transfer by acceptor saturation. Eur. Biophys. J. 35, 115–129 (2008).

Harke, B. et al. Resolution scaling in STED microscopy. Opt. Express 16, 4154–4162 (2008).

Ishibashi, Y. et al. Multiphoton-gated cycloreversion reactions of photochromic diarylethene derivatives with low reaction yields upon one-photon visible excitation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 9, 172–180 (2010).

Marriott, G. et al. Optical lock-in detection imaging microscopy for contrast-enhanced imaging in living cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17789–17794 (2008).

Jańczewski, D., Tomczak, N., Han, M.-Y. & Vancso, G.J. Synthesis of functionalized amphiphilic polymers for coating quantum dots. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1546–1553 (2011).

Pellegrino, T. et al. Hydrophobic nanocrystals coated with an amphiphilic polymer shell: a general route to water soluble nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 4, 703–707 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of E.A.J.-E., who died on 29 September 2011. This study was supported by the Max Planck Society. S.A.D. and F.G. were supported by the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) and the Ministerio de Educación, Argentina. We thank the Department of Physical Biochemistry, MPIbpc, for the use of the TCSPC fluorimeter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.D. planned and carried out the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. F.G. built the spectrophotometer and helped with the synthesis and measurements. E.A.J.-E. supervised the initial steps of the project. T.M.J. supervised the project, analysed the data, modelled the system and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Notes 1-3, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References. (PDF 8760 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Díaz, S., Gillanders, F., Jares-Erijman, E. et al. Photoswitchable semiconductor nanocrystals with self-regulating photochromic Förster resonance energy transfer acceptors. Nat Commun 6, 6036 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7036

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7036

This article is cited by

-

Photochromic Quantum Dots

Russian Physics Journal (2022)

-

The Structure and Characterization of 3,4,5-Triiodo-2-Methylthiophene: An Unexpected Iodination Product of 2-Methylthiophene

Journal of Chemical Crystallography (2019)

-

Energy Transfer Sensitization of Luminescent Gold Nanoclusters: More than Just the Classical Förster Mechanism

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Probing the kinetics of quantum dot-based proteolytic sensors

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.