Abstract

The introduction of improved steam engines at the end of the 18th century marked the start of the industrial revolution and the birth of classical thermodynamics. Currently, there is great interest in miniaturizing heat engines, but so far traditional heat engines operating with the expansion and compression of gas have not reached length scales shorter than one millimeter. Here, a micrometer-sized piston steam engine is implemented in an optical tweezer. The piston is a single colloidal microparticle that is driven by explosive vapourization of the surrounding liquid (cavitation bubbles) and by optical forces at a rate between a few tens of Hertz and one kilo-Hertz. The operation of the engine allows to exert impulsive forces with optical tweezers and induce streaming in the liquid, similar to the effect of transducers when driven at acoustic and ultrasound frequencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last two decades heat engines have been miniaturized using different fabrication and control methods to explore new ways to power small devices and periodically displace microscopic objects1,2,3. Environmental fluctuations can have a marked effect in the operation of microscopic heat engines. Recently, it was shown that a micrometer-sized heat engine can operate with a classical Stirling cycle between two heat baths (TC=22 °C, TH=90 °C) in an environment where the engine dynamics are dominated by Brownian fluctuations3. The reported mean value of the extracted work w per cycle is 0.11kBTC=4.5 × 10−22 J, with maximum mean power w/τ for τ=7 s, corresponding to a rate of 0.14 Hz.

Here a micrometer-sized piston steam engine is implemented in an optical tweezer, where a single microparticle is driven by microscopic explosions resulting from explosive vapourization and optical forces. The mean work per cycle exceeds the amount generated by the stochastic heat engine3 by six to eight orders of magnitude, while the frequency and maximum displacements are at least two orders of magnitude larger.

Results

Engine cycle

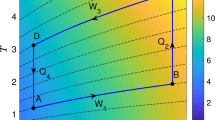

In each cycle a microscopic volume of water is superheated above the normal boiling or saturation temperature, the superheated liquid is unstable and relaxes to an equilibrium saturated state with the nucleation of a vapour cavitation bubble (explosive vapourization). Figure 1a shows the phase diagram projected in pressure p and temperature T that is commonly used to describe superheating4. The two continuous lines are the binodal and the spinodal. The binodal is the saturation curve Tsat(p) where the p/Tsat pairs can be calculated from the steam table for the saturated water line. The spinodal represents the limit at which the liquid can be superheated Tsp(p). The dotted line depicts the isobaric heating path at atmospheric pressure p0 in the engine cycle (Fig. 1a, 1→3), where the liquid is superheated reaching a temperature Tcav (Tsat(p0)<Tcav≤Tsp(p0)). The relaxation to the equilibrium saturated state at the binodal p/Tsat (Fig. 1a, 3→4) results in a large pressure rise and the explosive expansion of the saturated vapour (cavitation bubble).

(a) Phase diagram to describe the cycle, p0=0.1 MPa, Tcav is the temperature at which the superheated liquid relaxes with the nucleation of a bubble. Tsp is the spinodal temperature or superheat limit at a p0. pc=22 MPa and Tc=373.9 °C are the critical pressure and temperature for water. (b) Microparticle trajectory in the optical tweezer. (1–2) Optical forces attract the particle towards the focus heating it at atmospheric pressure p0, (2–3) increase in speed and heating rate results in superheated liquid at the surface, (3-4-1) explosive vaporization with adiabatic expansion pushes the microparticle close to the initial position.

The relaxation of a superheated liquid involves density fluctuations that eventually grow creating an exploding vapour bubble as described by the classical nucleation theory (homogeneous/heterogeneous)5 and spinodal decomposition at the superheat limit (Tsp)6. Experiments that have used current pulses to heat thin films and filaments immersed in water have reported temperatures Tcav at p0 around 302 °C (refs 7, 8), which correspond to pressure rises of 8.7 MPa (at the binodal). However, in general, reported values of Tcav are scattered in a wide range of temperatures9,10,11,12,13 showing that the results are very sensitive to the heating rate, surface properties of the heater and contaminants in the liquid. In this experiment Tcav is not measured, but the relevant parameters about the explosion are derived from the maximum bubble size.

Figure 1b shows the microparticle (piston) trajectory in the optical tweezer at different steps of the cycle. The microsphere absorbs at the trapping laser wavelength (975 nm) and it is heated by linear absorption. The liquid (water) is transparent at the laser wavelength.

The cycle starts with the particle below the geometrical focus or waist of the beam (step 1 in Fig. 1a,b), where the temperature is below the saturation temperature at p0. Then, the particle is attracted and pushed towards the waist by optical gradient and scattering forces. As the particle gets closer to the geometrical focus (1→2) the intensity increases, raising the surface temperature of the bead and the steepness of the trapping potential. The temperature increase is larger at the bead surface that is closer to the focal volume of the trapping beam. Hence, the liquid in contact with that surface reaches the highest temperatures. Closer to the focus, the displacement of the microparticle (2→3) is sufficiently fast that the liquid in contact with the top surface is suddenly superheated reaching Tcav at p0 (3). The superheated liquid relaxes (3→4) by nucleating a vapour bubble that later collapses under the hydrostatic pressure of the surrounding liquid. The microsphere is driven away by the bubble expansion close to the starting position (1) in the subsaturated water region where the cycle starts again.

Experimental implementation of the engine

The experiments are done in a standard optical tweezer set-up. The colloid solution is a dilute aqueous suspension of monodisperse microparticles (1.05 or 3.16 μm diameter 2Rp, Promag Bangs) that absorb at the trapping laser wavelength (975 nm). The laser is focused by a × 100 (1.25 NA, oil) microscope objective. The dynamics are detected with a high speed video recorder at frame rates of 300,000 frames per second (fps), with transverse/axial resolutions of 50/100 nm and 100/400 nm for 3- and 1-μm particles, respectively. The videos have a duration between 0.15 and 0.3 s. The algorithm to extract the three dimensional position is described in the Methods section.

The engine works for optical powers P above a threshold ~46 mW, where the heating rate at some point in the trajectory is sufficiently large to superheat the surface of the particle that is closer to the waist of the trapping beam, inducing explosive vapourization. At low P up to 24 mW, the particle can be trapped just like in regular optical tweezers, as the intensity is not sufficiently large to increase the temperature to the saturation value. For larger powers between 25 and 45 mW, it may be possible to achieve the saturation temperature and vapour may appear at the surface of the particles resulting in ejection from the trap. Experiments were done at P between 52 and 84 mW. However, the results mainly depend in the particle size Rp.

Figure 2a shows selected frames from a single cycle of a 3-μm particle with P=58 mW. The first three frames (from −33.3 ms to −167.7 μs) show the particle approaching the focus from below, becoming less fuzzy. The point of closest approach to the waist is reached at t=−3.3 μs and the surface closer to the waist has been superheated. At t=0 μs explosive vapourization is captured in one frame, where a blurred image of the explosion shows the bubble pushing the particle below the focus of the microscope objective. In the next frame t=3.3 μs, the bubble has vanished (collapsed by the hydrostatic pressure of the surrounding liquid) and the particle is close to the starting position where the cycle restarts. No vapour is observed at any frames before the explosion. The full microparticle trajectory for the cycle depicted in Fig. 2a is shown in Fig. 2b, where the positions (X(t), Y(t), Z(t)) are measured relative to the location of the geometrical focus. As the particle gets closer to the focus and the optical gradient force increases, the width of the Brownian fluctuations decreases (Fig. 2b); this is similar to compression in the stochastic heat engine3. Figure 2c shows a few cycles in the XY plane where it is easier to observe the direction of the engine that is constantly changing due to fluctuations that affect the trajectory. In Fig. 2d, the particle distance  measured relative to the position of the geometrical focus is plotted for a 3-μm and a 1-μm particle (P=58 mW, see Supplementary Movies 1 and 2).

measured relative to the position of the geometrical focus is plotted for a 3-μm and a 1-μm particle (P=58 mW, see Supplementary Movies 1 and 2).

(a) Selected frames from a singe cycle of a 3-μm particle. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Full trajectory for the cycle shown in a. (c) Trajectory for a few cycles projected in the xy plane. (d) distance  measured relative to the position of the geometrical focus. See Supplementary Movies 1 and 2.

measured relative to the position of the geometrical focus. See Supplementary Movies 1 and 2.

For each cycle, the maximum displacement induced by the explosion is defined as ΔD (Fig. 2d), which is measured for 52 and 382 cycles at different P for the 3- and 1-μm particles, respectively. ΔD3 μm=7.6±1 μm and ΔD1 μm=2.3±0.6 μm. The distance of closest approach for a given cycle is Dmin (defined as the minimum distance between the bead center and the geometrical focus), which is about 5 μm for the 3-μm particles and 2.8 μm for the 1-μm beads. The measurements are summarized in Table 1.

The measured cycle frequency f is in the following intervals f3 μm=(23, 48) Hz and f1 μm=(357, 1,025) Hz. The microparticle trajectory has a fast motion during the explosion and then a slow return with optical forces. Hence, the cycle frequency essentially depends on the maximum displacement ΔD and the mean speed during the slow return. The speed can be estimated by assuming that the optical force is constant and balanced by the drag, which is given by Stokes law F=6πμRpv (μ is the dynamic viscosity and v the velocity). In this way f=|v|/ΔD∝1/(RpΔD). The expected frequency ratio f1 μm/f3 μm can be estimated assuming that the optical force is the same for both sizes. In this way f1 μm/f3 μm~ΔD3 μmR3 μm/(ΔD1 μmR1 μm)~12.75. The predicted frequency range for the smaller microspheres should be a factor of 12.75 larger than the measured frequency interval of the 3-μm particles f1 μm~12.75f3 μm=(293, 612) Hz, which partially overlaps with the measured cycle frequencies for the 1-μm particle f1 μm=(357, 1025) Hz. The optical force is proportional to  . In this case the assumption that it is constant and has the same value for both particle sizes yields a reasonable approximation, because the difference in volume

. In this case the assumption that it is constant and has the same value for both particle sizes yields a reasonable approximation, because the difference in volume  is compensated with a stronger intensity gradient ∇I for the 1-μm particles that are always closer to the focus.

is compensated with a stronger intensity gradient ∇I for the 1-μm particles that are always closer to the focus.

The measured frequencies and maximum displacements ΔD per cycle show that there is a trade-off between operating frequency and expansion ratio as described in14, as increasing one reduces the other.

The engine is very stable for 3-μm particles, which could oscillate for more than 20 min with no sign of deterioration, while with 1-μm particles it is unstable and worked for tens of seconds.

Bubble dynamics

The dynamics of the cavitation bubble (radius R(t)) that result from explosive vapourization are extremely fast and are not resolved by the high speed video recorder. The bubble appears blurred in a single frame (Fig. 3a,b, centre frames) that is used to extract the maximum bubble radius Rmax. During expansion, the bubble does work against the hydrostatic pressure (p0=0.1 MPa) of the surrounding liquid, while the vapour pressure pv and temperature inside decrease at a very fast rate. Once the bubble reaches the maximum size  the kinetic energy has converted into potential energy and the vapour inside has reached the room temperature values. Then the bubble collapses under the static pressure of the surrounding liquid. The collapse time τC of a spherical bubble can be calculated from the Rayleigh relation derived from the inertial Rayleigh equation15,16.

the kinetic energy has converted into potential energy and the vapour inside has reached the room temperature values. Then the bubble collapses under the static pressure of the surrounding liquid. The collapse time τC of a spherical bubble can be calculated from the Rayleigh relation derived from the inertial Rayleigh equation15,16.

(a) Selected frames of a 3-μm particle before, during the explosion and after recorded at 300,000 fps. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Selected frames for a 1-μm particle recorded at 500,000 fps before, during and after the explosion, these videos were not used to extract trajectories. Scale bar, 5 μm. (c) Parameters to describe the interaction between the bubble and the microparticle. δ′ is the distance from the centre of the particle to the origin of the bubble, which is at the surface of the particle.

where pv is the vapour pressure inside the fully expanded bubble (2,330 Pa, at T0=20 °C) and ρl is the water density.

The time elapsed between the initial expansion of the bubble and the collapse is the lifetime or oscillation time τosc, which for spherical bubbles τosc=2τC (refs 17, 18). Hence, Rmax is reached in τC.

The energy of the bubble is also related to the maximum bubble radius Rmax

The measured Rmax are Rmax−3 μm=3.4±0.3 μm and Rmax−1 μm=1.6±0.1 μm. These measurements are not correlated with P, suggesting that the initial pressure and volume of the superheated vapour are similar in the explored range of P for each particle size.

The collapse times are calculated using equation (1) and the measured Rmax, τC−1 μm=148±12 ns and τC−3 μm=317±30 ns. These very brief timescales explain why the bubble only appears in a single frame.

The bubble energies are calculated from equation (2) and are between 10−12 and 10−11J (Table 1).

Bubble-particle interaction

The maximum displacement ΔD for a given cycle that results from the interaction with the cavitation bubble depends on the initial distance between the centre of the particle and the centre of the bubble δ′ and Rmax (Fig. 3c). If those distances are non dimensionalized as δ=δ′/Rmax and Δx=ΔD/(2Rp), then the interaction is described by a single master curve19. For δ in the interval (0, 0.7) the particle is pushed away (rejection), δ=0.7 corresponds to a neutral region Δx=0, while for δ>0.7 there is attraction.

In these experiments the initial distance from the centre of the bubble to the centre of the particle is simply the radius of the particle (δ′=Rp), as the bubble originates at the surface of the particle (Fig. 3c). In this way δ is in the rejection region, δ1 μm~0.33 and δ3 μm~0.47, resulting in a positive displacement that can be calculated from the master curve of19 Δx1 μm~2.5–3 and Δx3 μm~1.7–2; these values correspond to ΔD1 μm~2.5–3 μm and ΔD3 μm~5.4–6.3 μm similar to the measurements (Table 1).

Work done by the engine

The particle dynamics, speed v(t) and the magnitude of the acceleration a(t) are extracted from the distance data D(t) processed with standard left finite difference with fixed time step Δt=3.3 μs (300,000 fps videos). The maximum accelerations during the explosion (at t0) for the cycles analysed in Table 1 are amax−3 μm=2.02±0.59 × 105ms−2 and amax−1 μm=1.15±0.66 × 105ms−2. The values of amax are proportional to the largest forces and the largest contributions to the total work per cycle. However, the temporal resolution Δt is not sufficient to resolve the dynamics during the explosion, as the particle is displaced a distance Rmax in a time τC≪Δt. This results in an underestimation of speeds and accelerations only during the explosive expansion (one frame), since the expected accelerations should have an order of Rmax/τC2, which yield values of 7.3 and 3.4 × 107ms−2 for the 1- and 3-μm particles, respectively. In this way, the calculations that follow (with fixed Δt) for the maximum force and mean work per cycle can be considered lower bounds that are underestimated by at least two orders of magnitude.

The magnitude of the resultant force F(t) acting on the particle is calculated from the particle dynamics. During the explosion (a(t0)=amax, one frame), the impulsive force (maximum force in a cycle) is simply Fmax=Vpρpamax, where Vp is the particle volume and ρp the particle density. Notice that there is no added mass, as it is assumed that the particle moves with the velocity of the liquid that is displaced by the bubble during the explosion20. After the bubble collapses, the flow induced by the bubble ceases and the force is calculated considering the added mass F(t)=Vp(CAρl+ρp)a(t), with CA=(1/2) the added mass coefficient for a sphere and ρl is the density of water. The impulsive forces during the explosion are Fmax−3 μm=4.07±1.18 × 10−9N and Fmax−1 μm=9.24±5.36 × 10−11N.

The work done by the particle is w(t)=∫F(t)dD(t) where the numerical integration is done with the trapezoidal method. Plots of the work done by a 1-μm particle and by a 3-μm particle in the liquid as a function of time are shown in Fig. 4a,b. As expected, the work increases in sharp steps due to the large acceleration amax during the explosive expansion of the bubble. The mean work per cycle is  and

and  . A fraction of the mechanical energy of the explosion is transferred to the microparticle (piston) and it is estimated by the ratio

. A fraction of the mechanical energy of the explosion is transferred to the microparticle (piston) and it is estimated by the ratio  , which has the order of 5 × 10−5–6 × 10−4.

, which has the order of 5 × 10−5–6 × 10−4.

(a) Work done by a 1-μm particle. (b) Work done by a 3-μm particle. (c) Streaming induced by a 3-μm engine. The blue vectors show the average velocities (during 1 s) of the induced flow extracted from PIV. Close to the engine, the average velocities are ~80 μms−1 . (d) Change in direction by the oscillating particle results in different direction for the induced flow. Scale bar, 20 μm, the dotted circle indicates the position of the engine. Movie for c and d is in Supplementary Movie 3.

The average power is  , which lies in the intervals (3.3, 9.4) × 10−14W and (2.37, 4.94) × 10−13W for the 1- and 3-μm particles, respectively. If the engine volume is defined using the maximum bubble radius Rmax then the power density is

, which lies in the intervals (3.3, 9.4) × 10−14W and (2.37, 4.94) × 10−13W for the 1- and 3-μm particles, respectively. If the engine volume is defined using the maximum bubble radius Rmax then the power density is  , which yields about 3 kWm−3 for both particle sizes. The results of this subsection are summarized in Table 2.

, which yields about 3 kWm−3 for both particle sizes. The results of this subsection are summarized in Table 2.

Finally, the work done by the engine (3-μm) in the surrounding liquid results in streaming, which can be observed by seeding the liquid with neutrally buoyant 1-μm polystyrene microparticles, which are transparent to the laser wavelength and thus not heated by the beam (Fig. 4c,d). The flow induced by the engine is extracted from standard PIV (Thielicke, W., Stamhuis, E. J. PIVlab http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1092508). The vectors in Fig. 4c,d show the average velocities (during 1 s) of the induced flow. Close to the engine the average speeds are ~80 μms−1.

The effect of periodic cavitation (without the microbead piston) is a symmetric attractive flow around the bubble for particles located at a distance δ′>0.7Rmax~2.4 μm from the centre of the bubble as shown in ref. 19. The movement of the microparticle (piston) displaces liquid creating an asymmetry in the flow that depends in the oscillation direction, which is random (Fig. 4c,d, see Supplementary Movie 3). This effect is similar to streaming produced by oscillating liquid-gas boundaries driven by transducers or pulsed lasers 19,21,22,23.

Discussion

In this work, for the first time, a steam engine is implemented with a length scale of one micrometer. This study also shows that it is possible to exert impulsive forces with optical tweezers. Considering the underestimation of two orders of magnitude, the maximum forces during the explosive displacement of the microbead are in the range of 10−9−10−7N, three to five orders of magnitude larger than in regular optical tweezers (pN).

The mean work per cycle extracted from the microscopic steam engine is six to eight orders of magnitude (eight to ten considering underestimation) larger than in the stochastic heat engine3, while the cycle frequency is two to three orders of magnitude larger than in that study. The power density of ~3 kWm−3 (or 300 kWm−3 if the factor of 100 is considered) is much smaller than that of other microscopic heat engines. For example, the piezoresistive heat engine1 that operates with the compression and expansion of a solid has a power density of 36 GWm−3, which is larger than that of car engines (tens of MWm−3). However, some advantages of this implementation are that microfabrication is not required and that the engine operates in a regime dominated by fluctuations.

The microscopic steam engine could be used in applications that previously required pulsed lasers or transducers. For example, optical pumps in microfluidic applications24, cell poration21,22 and cell lysis25.

Methods

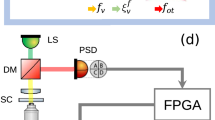

Experimental set-up

The trapping laser is a single mode fibre coupled diode with a wavelength of 975 nm focused by a microscope objective ( × 100, oil, 1.25 NA). The mean diameter of the microspheres (Promag, Bangs) are 1.05 and 3.16 μm (Promag 1 and 3, surfactant free, Bangs) with a density of 1,330 and 1,225 kgm−3, respectively. These particles contain magnetite (Fe3O4 and Fe2O3) and a unspecified polymer. The optical properties of these microparticles are not provided. A study on silica gels containing magnetite26 shows that the optical transmittance vanishes at wavelengths below 400 nm and increases to about 60% at 800 nm (largest wavelength in that work). The absorption coefficients decrease monotonically with increasing wavelength with the minimum also at 800 nm. If the optical properties of the magnetic microparticles are similar to the silica gels with magnetite, the high transmittance and low absorption in the near infra-red would be consistent with the ability to trap these particles at low optical powers and induce explosive vapourization for higher powers closer to the beam waist.

The aqueous solution with the microparticles is placed between two microscope coverslides (Number 1, 0.13–0.16 mm thick) separated with spacers with a height ~100 μm and sealed with nail polish. The video recorder is a Photron SA 1.1.

Image processing

The 3d dynamics are extracted from the high speed videos. First, all frames are divided by the background, then the images are processed with a 3 pixel averaging filter to remove some of the noise and the centre (in XY) is extracted with standard video microscopy techniques, with a resolution of 50 nm (±25 nm) for the 3-μm particles and 100 nm for the 1-μm particles (fewer points).

The axial position is extracted from the images by first doing a calibration in Z like with a quadrant photodiode (not used due to small linear range ~1 μm), videos are recorded under the same conditions of the experiment at each height. The sample is raised in steps of 125 nm with a piezo stage in closed loop for a total of 160 steps, starting at a position of Z=−16 μm to Z=4 μm (the geometrical focus is at Z=0). At each step Zi, the normalized intensity centred at the particle and averaged over the azimuthal angle is extracted for every value of  in a range from (0, 7 μm). Hence, for each axial position Zi an f(Zi,ρ) is extracted for several frames. The signal is averaged for at least 80 frames. Sample signals are shown in Fig. 5a. Interpolation is done between the 160 samples f(Zi,ρ) to get a continuous function f(Z,ρ). Calibrations were done with several particles to take into account small variations in the size. Figure 5b shows sample fits from videos recorded at 300,000 fps. The axial resolution is 100 nm for 3-μm particles and 400 nm in the case of 1-μm particles.

in a range from (0, 7 μm). Hence, for each axial position Zi an f(Zi,ρ) is extracted for several frames. The signal is averaged for at least 80 frames. Sample signals are shown in Fig. 5a. Interpolation is done between the 160 samples f(Zi,ρ) to get a continuous function f(Z,ρ). Calibrations were done with several particles to take into account small variations in the size. Figure 5b shows sample fits from videos recorded at 300,000 fps. The axial resolution is 100 nm for 3-μm particles and 400 nm in the case of 1-μm particles.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Quinto-Su, P.A. A microscopic steam engine implemented in an optical tweezer. Nat. Commun. 5:5889 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6889 (2014).

References

Steeneken, P. G. et al. Piezoresistive heat engine and refrigerator. Nat. Phys. 7, 354–359 (2011).

Epstein, A. H. Millimeter-scale, micro-electronechanical systems gas turbine engines. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 126, 205–226 (2004).

Blickle, V. & Bechinger, C. Realization of a micrometre-sized stochastic heat engine. Nat. Phys. 8, 143–146 (2012).

Vogel, A. & Venugopalan, V. Mechanisms of pulsed laser ablation of biological tissues. Chem. Rev. 103, 577–644 (2003).

Caupin, F. & Herbert, E. Cavitation in water: a review. C. R. Phys. 7, 1000–1017 (2006).

Debenedetti, P. Metastable liquids: concepts and principles Princeton University Press (1996).

Skripov, V. P. & Pavlov, P. A. Explosive boiling of liquids and fluctuation nucleus formation. High Temp. 8, 782–787 (1970).

Glod, S., Poulikakos, D., Zhao, Z. & Yadigaroglu, G. An investigation of microscale explosive vaporization of water on an ultrathin Pt wire. Int. J. Heat. Mass Trans. 45, 367–379 (2002).

Apfel, R. E. Water superheated to 279.5°C at atmospheric pressure. Nat. Phys. Sci. 238, 63–64 (1972).

Thomas, O. C., Cavicchi, R. E. & Tarlov, M. J. Effect of surface wettability on fast transient microboiling behavior. Langmuir 19, 6168–6177 (2003).

Apfel, R. E. Vapor nucleation at a liquid-liquid interface. J. Chem. Phys. 54, 62–63 (1971).

Park, H. K., Grigoropoulos, C. P., Poon, C. C. & Tam, A. C. Optical probing of the temperature transients during pulsed-laser induced boiling of liquids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68, 596–598 (1996).

Yavas, O., Schilling, A., Bischof, J., Boneberg, J. & Leiderer, P. Bubble nucleation and pressure generation during laser cleaning of surfaces. Appl. Phys. A 64, 331–339 (1997).

Peterson, R. B. Size limits for regenerative heat engines. Microscale Therm. Eng. 2, 121–131 (1998).

Rayleigh, L. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. Philos. Mag. 34, 94–98 (1917).

Plesset, M. S. & Prosperetti, A. Bubble dynamics and cavitation. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 9, 145–185 (1977).

Godwin, R. P., Chapyak, E. J., Noack, J. & Vogel, A. Aspherical bubble dynamics and oscillation times. Proc. SPIE 3601, 225–236 (1999).

Ohl, C. D., Lindau, O. & Lauterborn, W. Luminescence from spherically and aspherically collapsing laser induced bubbles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 393–396 (1998).

Gonzalez-Avila, S. R., Huang, X., Quinto-Su, P. A., Wu, T. & Ohl, C. D. Motion of micrometer sized spherical particles exposed to a transient radial flow: attraction, repulsion, and rotation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 074503 (2011).

Arora, M., Ohl, C. D. & Mørch, A. Cavitation inception on microparticles: a self-propelled particle accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 174501 (2004).

Marmottant, P. & Hilgenfeldt, S. Controlled vesicle deformation and lysis by single oscillating bubbles. Nature 473, 153–156 (2003).

Prentice, P., Cuschieri, A., Dholakia, K., Prausnitz, M. & Campbell, P. Membrane disruption by optically controlled microbubble cavitation. Nat. Phys. 1, 107–110 (2005).

Zhao, X., Quinto-Su, P. A. & Ohl, C. D. Dynamics of magnetic bubbles in acoustic and magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 024501 (2009).

Dijkink, R. & Ohl, C. D. Laser-induced cavitation based micropump. Lab. Chip. 8, 1676–1681 (2008).

Quinto-Su, P. A. et al. Examination of laser microbeam cell lysis in a PDMS microfluidic channel using time-resolved imaging. Lab. Chip. 8, 408–414 (2008).

Yasumori, A., Matsumoto, H., Hayashi, S. & Okada, K. Magneto-optical properties of silica gel containing magnetite fine particles. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Tech. 18, 249–258 (2000).

Acknowledgements

I thank P. Quinto-Diez for discussions about heat engines. This work is partially funded by the following grants: CONACYT (153821) and DGAPA, UNAM (PAPIIT TB100312).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A.Q.S. conceived and designed the research, performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Movie 1

3 μm particle engine. The duration of the movie is 300 ms and the frame height is 30.0 μm. (AVI 4411 kb)

Supplementary Movie 2

1 μm particle engine. The duration of the movie is 150 ms and the frame height is 11.4 μm. (AVI 1242 kb)

Supplementary Movie 3

3 μm particle engine with 1 μm polystyrene tracer particles. The duration of the movie is 10 s (real time) and the frame height is 60.6 μm. (AVI 2904 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quinto-Su, P. A microscopic steam engine implemented in an optical tweezer. Nat Commun 5, 5889 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6889

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6889

This article is cited by

-

Tunable Brownian magneto heat pump

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Tuning the performance of a micrometer-sized Stirling engine through reservoir engineering

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Shift a laser beam back and forth to exchange heat and work in thermodynamics

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Rolling membrane powered by low-temperature steam as a new approach to generate mechanical energy

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.