Abstract

Upon stimulation by Wnt ligands, the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway results in the stabilization of β-catenin and its translocation into the nucleus to form transcriptionally active complexes with sequence-specific DNA-binding T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family proteins. In the absence of nuclear β-catenin, TCF proteins act as transcriptional repressors by binding to Groucho/Transducin-Like Enhancer of split (TLE) proteins that function as co-repressors by interacting with histone deacetylases whose activity leads to the generation of transcriptionally silent chromatin. Here we show that the transcription factor Ladybird homeobox 2 (Lbx2) positively controls the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway in the posterior lateral and ventral mesoderm of the zebrafish embryo at the gastrula stage, by directly interfering with the binding of Groucho/TLE to TCF, thereby preventing formation of transcription repressor complexes. These findings reveal a novel level of regulation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway occurring in the nucleus and involving tissue-specific derepression of TCF by Lbx2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway plays a variety of crucial roles during development, regeneration and carcinogenesis1. Extensive analyses of the mechanisms regulating its activity have shown that Wnt signalling acts by stabilizing the transcription co-activator β-catenin by preventing its phosphorylation-dependent degradation2,3. In the absence of Wnt signals, β-catenin is degraded in the cytoplasm via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The T-cell factor (TCF) transcription factor binds to DNA and functions as a transcriptional repressor by binding to members of the Groucho (Gro)/TLE family4,5,6,7, which interact with histone deacetylases8 whose activity maintains the chromatin in a transcriptionally inactive state. Upon Wnt stimulation, a cascade of events is initiated that results in the translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus, where it binds to TCF and promotes formation of transcriptionally active complexes3,7. Currently, Wnt/β-catenin signalling is thought to be controlled by the amount of β-catenin translocated into the nucleus3, where its activity is modulated by interaction with specific co-activators and specific nuclear antagonists7,9.

In this report, we show that the homeobox gene ladybird (lbx2), which is present at the gastrula stage in territories adjacent to the Wnt8a expression domain, is essential for the activity of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway in ventral and lateral mesodermal cells. Loss of Lbx2 function mimics Wnt8a morphant/mutant phenotype, while gain of function of Lbx2 enhances activity of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway resulting in the posteriorization of the embryo. This enhancement does not result from nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in cells of the anterior part of the embryo but from a derepression of TCF through the sequestration of the co-repressor Gro by Lbx2. This shows that the regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway is not restricted to the well-characterized control of the balance between degradation and stabilization/nuclear translocation of β-catenin but that the level of co-repression of TCF by Groucho proteins is tightly controlled. In this context, the Lbx2 transcription factor, in the nonaxial mesoderm (that is in territories adjacent to the source of Wnt expression from blastula to early somitogenesis), promotes the transcription of Wnt/β-catenin target genes through the attenuation of the Gro/TLE co-repressing activity. Altogether this study identifies a novel level of regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling and establishes that the transcriptional repression of this pathway is an active and tightly regulated process.

Results

Lbx2 and Wnt8a loss- and gain of function are very similar

Lbx2, one of three lbx genes identified in zebrafish10, is the first lbx gene to be expressed during development11. Transcripts of this gene accumulate during gastrulation and early somitogenesis, in the segmental plate as well as in the ventral mesoderm in territories adjacent to and partially overlapping with wnt8a (Fig. 1a–h), suggesting that lbx2 may be involved in the regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. We investigated this hypothesis by performing loss- and gain-of-function experiments. Lbx2 morpholino knockdowns (MO-KD) result in embryos displaying, at the beginning of somitogenesis, an elongated shape characteristic of a dorsalization phenotype (Fig. 1i,j). At 24 h post fertilization (hpf), lbx2 morphants lack ventral and posterior portions of the trunk and tail (Fig. 1k,l), a phenotype also observed for wnt8a loss of function12 (Fig. 1m). This dorsalization phenotype was confirmed by using specific molecular markers that reveal the disappearance of the ventral and lateral margin (Fig. 1n,o) and of the presumptive epidermis (Fig. 1p,q). Finally, the expression of chordin, the main antagonist of the Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (morphogens that specify ventral and lateral cell fates), extend into the posterior lateral and ventral mesoderms at gastrula stages in both lbx2 (Fig. 1r–t) and wnt8a (Fig. 1u) morphants. The multiple similarities between the wnt8a and lbx2 loss-of-function phenotypes strongly suggest that Lbx2 is involved in the regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway.

(a–h) lbx2 and wnt8a are expressed in adjacent and partially overlapping territories during gastrula and early somitogenesis stages in wild-type embryos. (a,e) early gastrula (b,c,f,g) mid-gastrula, (d,h) early somitogenesis. Arrowheads in a,e indicate the position of the most vegetal marginal cells. (i) WT and (j) lbx2 morphant at early somitogenesis. (k) WT (l) lbx2 and (m) wnt8a morphants at 24 hpf. (n,o) Expression of the ventral margin marker eve1 and (p,q) of the presumptive epidermis marker foxi1 in (n,p) WT and (o,q) lbx2 morphants. (r–u) Expression of chordin (chd) in (r) WT (s,t) lbx2 morphant and (u) wnt8a morphants at the gastrula stage. Embryos are (i–m,p,q,t,u) in lateral view, (c,g) vegetal pole view, (n,o,r,s) animal pole view, (a,b,e,f) dorsal view anterior to the top and (d,h) dorsal view anterior to the left. Scale bar in a is equivalent to 200 μm (a–h,n–u). Scale bar in i is equivalent to 100 μm (i–m).

Additional evidence in favour of this hypothesis comes from gain-of-function experiments. Injection of 50 pg of lbx2 mRNA at the one-cell stage results in a strong anterior expansion, at the time of gastrulation, of the expression territories of sp5l, a specific target of the Wnt8a zygotic activity, comparable to what is seen in embryos injected with Wnt8a mRNA13 (Fig. 2a–c). At 24 hpf, Lbx2-overexpressing embryos display posteriorization phenotypes characterized by a reduction or a complete deletion of the forebrain and eyes (Fig. 2d,e,g,h). This is identical to a Wnt8a zygotic gain-of-function phenotype14, supporting the hypothesis that Lbx2 positively regulates the zygotic Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. In agreement with this hypothesis, the deletion of the head in embryos overexpressing Lbx2 can be fully rescued by a MO knockdown of wnt8a that results in a decrease in the activity of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway (Fig. 2f,i; Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Compared with (a) WT, overexpression of Lbx2 (injection of 40 pg mRNA) results (b) in a strong extension of sp5l expression towards the animal pole similar to what is seen (c) with overexpression of Wnt8a (injection of 25 pg mRNA). Compared with WT (d,g), embryos overexpressing lbx2 show anterior head truncation at 36 hpf (e) and complete lack of the telencephalic marker emx1 (arrowhead) at early somitogenesis (h). (f,i) These phenotypes are fully rescued by MO knockdown of wnt8a. (j) TopFlash transcription assay: relative luciferase activity was measured after overexpression of Wnt8a and Lbx2 by mRNA injections or after MO knockdown. Data are from three independent experiments and expressed as the means with s.d.’s. Scale bar in d is equivalent to 100 μm (d–f). Scale bar in g is equivalent to 200 μm (a–c,g–i).

The involvement of Lbx2 in the regulation of the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway has been further established in transcription assays using a TCF-sensitive luciferase reporter gene (TopFlash)15. Injection of the TopFlash vector into the embryo results in transcription of luciferase (because of the endogenous Wnt/β-catenin activity). Expression of this reporter gene is strongly enhanced after co-injection of either Wnt8a mRNA or lbx2 mRNA (Fig. 2j). Conversely, a decrease in luciferase transcription is observed for wnt8a as well as for lbx2 MO knockdowns (Fig. 2j). Taken together, the phenotypic analysis, the rescue experiments and the β-catenin-mediated transcription assays described above demonstrate that Lbx2 promotes Wnt/β-catenin signalling in the zebrafish embryo (summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1a–c).

Lbx2 does not regulate nuclear translocation of β-catenin

As Lbx2 and Wnt8a expression territories are only partially overlapping (Fig. 1a–h), Lbx2 is unlikely to act on the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway by activating transcription of Wnt8a. In support of this conclusion, expression of Wnt8a and Wnt3a is not affected in lbx2 morphants and gain of function of Lbx2 does not result in inducing expression of canonical Wnts such as Wnt8a or Wnt3a (Supplementary Fig. 2). This led us to hypothesize that Lbx2 may act by regulating the translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus; most of the known modes of regulation of the canonical Wnt pathway converge at this step3. If this hypothesis is true, loss of Lbx2 function will result in a decrease in the amount of nuclear β-catenin in the posterior lateral and ventral mesodermal cells that express this gene. In addition, similar to what is observed for gain of function of Wnt8a, we also predict that a gain of function of Lbx2 will promote nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in all cells of the embryo.

Our analysis of the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in response to Lbx2 loss- and gain of function (Fig. 3) refutes this hypothesis. In a wild-type gastrula embryo, β-catenin is found in nuclei of the posterior ventral and lateral mesodermal cells that express Lbx2 as well as in adjacent ectodermal cells (that do not express Lbx2). In the same territories, in Wnt8a morphant embryos, β-catenin is still present at the plasma membrane but is absent from the nuclei. Although Lbx2 and Wnt8a loss of function result in a very similar dorsalization phenotype, in the Lbx2 morphant, β-catenin is found in nuclei of posterior ventral and lateral mesodermal cells as well as in the adjacent ectodermal cells as observed in wild-type (WT) gastrula (Fig. 3a–c). This demonstrates that, while the canonical Wnt signalling activity is decreased in the Lbx2 morphant, the nuclear translocation of β-catenin is not affected.

(a–f) Immunolocalization of β-catenin on (a–c) cryosections and (d–f) whole-mount mid-gastrula embryos. (a) WT, (b) Wnt8a morphant, (c) Lbx2 morphant. Lower panels in a–c are close-up views of the rectangular regions of the embryos in the upper row with left: β-catenin (green), centre: nuclei labelled with DAPI (blue) and right: merge of the two channels. This boxed domain corresponds to the posterior ventral domain where Lbx2 is expressed in the mesoderm (indicated with red dotted lines). (d–f) Lateral views of embryos, (d) WT, (e,f) injected with (e) 25 pg Wnt8a mRNA or (f) 40 pg Lbx2 mRNA showing that, whereas (e) gain of function of Wnt8a results in an accumulation of β-catenin into the nuclei of all cells of the gastrula, (f) the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin for an embryo overexpressing Lbx2 RNA is similar to (d) WT, with the animal pole devoid of nuclear β-catenin. Bottom row: close-up of the animal pole region in animal pole view for the different conditions used. Scale bar in a is equivalent to: 80 μm (a–c top), 20 μm (a–c bottom), 100 μm (d–f top) and 10 μm (d–f bottom).

Gain of function of Wnt8a results in the accumulation of β-catenin into the nuclei of all cells of the gastrula from the margin to the animal pole (Fig. 3d,e). However, while gain of function of Lbx2 results in posteriorization phenotypes, mimicking Wnt8a gain of function, the pattern of nuclear accumulation of β-catenin observed in Lbx2-overexpressing embryos is similar to that seen in the wild-type control; animal pole cells are devoid of nuclear β-catenin (Fig. 3f). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that Lbx2 regulates a step in the zygotic Wnt signalling pathway downstream of the translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus.

Lbx2 interferes with the binding of Gro to TCF7L1 in vitro

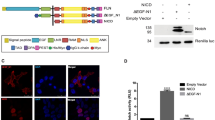

Lbx2 is a transcription factor that contains, in its N-terminal domain, an engrailed homology 1 (eh1) motif, which has been associated with repressive activity and directly interacts with the WD domain located in the carboxy-terminal end of the TCF co-repressor Gro16. In agreement with this report, we found that Lbx2 and Groucho2 can be co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 4a,b). Both the full-length and the carboxy-terminal truncated forms of Lbx2 that retain the eh1 domain can co-immunoprecipitate with full-length Gro2 as well as with the WD repeat domain of Gro2. However, an amino-terminal truncation of Lbx2, lacking the eh1 motif, does not co-immunoprecipitate with Gro2. Similarly, Lbx2 does not co-immunoprecipitate with a carboxy-terminal truncation of Gro2 lacking the WD repeat domain (Fig. 4b).

(a) Schematic of the constructs used for the co-immunoprecipitation assays. (b) After co-transfection, immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using an anti-myc antibody. Total cell lysates (TCLs) and the immunoprecipitated complex were analysed with western blot analysis (WB) using anti-myc or anti-flag antibodies. While Lbx2 and Lbx2ΔC interact with Gro2, Lbx2ΔN (lacking the eh1 domain) is unable to bind to Gro2. Lbx2 binds to the carboxy terminus of Gro2 (Gro2WD) but not to C-terminal truncated Gro2 lacking the WD domain (Gro2ΔC). (c) The interaction between Flag-Gro2 and HA-TCF7L1 was demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation of TCF7L1 using an anti-Flag antibody. The interaction between these two proteins is progressively attenuated when increasing amounts of Lbx2 (from 0.2 to 1.5 μg) are co-transfected. Images of the full blots presented in b,c are available in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Because Gro2 acts as a co-repressor by binding directly to TCF7L1 (formerly TCF3) and because Lbx2 regulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and is able to bind to Gro2, we hypothesized that Lbx2 may act by altering the interaction between Gro2 and TCF7L1. Using a co-immunoprecipitation assay, we found that co-transfection of increasing amounts of Lbx2 decreases the interaction between TCF7L1 and Gro2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4c). This suggests that Lbx2 may regulate the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway by preventing the interaction of Gro2 with TCF7L1 resulting in the attenuation of its co-repressor activity.

Lbx2 modulates interaction between Gro and TCF in vivo

This conclusion, based on the analysis of protein–protein interactions, has been confirmed using in vivo functional assays (Fig. 5a). A strong overexpression of Lbx2 activates maternal β-catenin signalling resulting in induction of chordin expression in the lateral and ventral early blastula margin. However, a Lbx2 variant, in which the eh1 domain has been deleted or mutated, is completely devoid of activity establishing the essential role of this domain for Lbx2 function. On the other hand, overexpression of either full-length Gro2 or of ΔC-Gro2 that lacks the WD domain (and hence the ability to bind Lbx2) leads to decreased expression of chordin. Lbx2 is able to rescue the repression of chordin expression resulting from overexpression of the full-length Gro2 but is unable to rescue the repression induced by ΔC-Gro2. The same result is obtained when overexpressing a truncated form of Lbx2 (Lbx2-ΔHMD-ΔCt) that lacks the carboxy-terminal end of the protein, containing the homeodomain, but retains the eh1 domain and the nuclear localization signal (nls). Therefore, these results show that binding of Lbx2 to DNA is not required for its functional interaction with Gro2. Finally, truncated forms of Lbx2 that lack the nuclear localization signal (Lbx2 Δnls; Lbx2 Δnls ΔHMD ΔCt) have no activity showing that the interaction between Lbx2 and Gro2 occurs in the nucleus.

(a) Top left: schematic showing the different domains within the Lbx2 and Gro2 proteins. Top right and bottom: expression of chordin (chd) visualized by in situ hybridization at the dome stage: dark blue indicates a decrease in Wnt/β-catenin activity, light blue indicates a wild-type level of Wnt/β-catenin activity and yellow indicates an increase in Wnt/β-catenin activity. The graph indicates the percentage of the different phenotypes of chordin expression observed after injection of mRNAs coding for full-length, truncated or mutant forms of Lbx2 (100 pg), for Gro2 (500 pg), for the truncated form of Gro2 lacking the WD-binding domain (Gro2ΔCt, 500 pg) either alone or in combination (as indicated on the left) and for weak overexpression of Lbx2 (Lbx2 weak, injection of 15 pg Lbx2 mRNA) in WT and in Gro1–Gro2 double morphants (Gro1–Gro2 MOs). β-cat. BD: β-catenin-binding domain, Ct: carboxy-terminal domain, eh1 BD: eh1-binding domain, HMD: homeodomain, nls: nuclear localization signal, Nt: amino-terminal domain, TCF BD: TCF-binding domain. (b) TopFlash transcription assay: relative luciferase activity was measured after overexpression by mRNA injections of Gro2 (500 pg) and Gro2ΔCt (lacking the WD repeat domain, 500 pg) either alone or in combination with increasing amounts of Lbx2 mRNA (50, 100, 200 pg). Data are from three independent experiments and are expressed as the means with s.d.’s. (c) Ventral extension of chordin expression (extended or circularized) visualizing the dorsalization phenotype resulting from Lbx2 MO injection (grey bar) can be partially rescued by co-injection of 150 pg mRNA coding for a truncated form of TCF7L1 lacking the Gro-binding domain (TCF7L1ΔGroBD—black bar). Injection of 150 pg of TCFΔGroBD mRNA alone (white bar) has almost no effect on chordin expression. Data are from three independent experiments with each group comprising more than 100 embryos. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test. Scale bar in a is equivalent to 200 μm.

These observations show that the WD domain of Gro2 is not essential for the interaction with TCF, since the C-terminal truncated form of Gro2 retains its ability to attenuate chordin expression. This is consistent with the previous finding that Gro interacts with TCF through its N-terminal Q-rich domain17. However, in the absence of the WD domain, Lbx2 is unable to interact with Gro2 and therefore cannot attenuate its repressive activity. We further demonstrate this using a TopFlash luciferase assay (Fig. 5b). As expected, injection of Gro2 mRNA represses the luciferase transcription. This effect is rather weak because zebrafish gro/TLE genes are strongly expressed both maternally and zygotically18, and therefore addition of Gro2 mRNA only modestly increases the endogenous repression activity. Overexpression of Lbx2 rescues this repression and even stimulates luciferase transcription. However, Lbx2 is unable to rescue the repression induced by the injection of ΔCt-Gro2. This shows that, in the absence of the WD domain, Lbx2 is unable to inhibit the function of Gro2 as a co-repressor of TCF. We conclude that Lbx2 exerts its effect on the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway by interacting with Gro2 at the level of the WD domain, decreasing its binding to TCF and attenuating its repressive activity.

Gain-of-function experiments may give rise to artifactual results. Therefore, it is possible that the titration of Gro by overexpression of Lbx2 may not be physiological and that the model of action we propose may be the consequence of transcriptional squelching, which is thought to result from titration by an overexpressed transcriptional protein of one or more essential transcription factors present in limiting amounts19. To rule out this explanation for our results, we investigated the ability of a modified form of TCF7L1, which lacks the domain responsible for the interaction with Gro (Gro binding domain, GroBD)5, to rescue the Lbx2 loss-of-function phenotype (Fig. 5c). This form of TCF7L1 (TCF7L1ΔGroBD) retains its ability to bind to DNA and to interact with β-catenin, which acts as a co-activator. Consequently, injection of TCF7L1ΔGroBD mRNA results in posteriorization phenotypes similar to those induced by overexpression of Wnt8a or of Lbx2 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). This phenotype can be rescued by attenuating Wnt8a activity by morpholino knockdown. This shows that, in the absence of binding to its co-repressor Gro, transcription of Wnt target genes occurs even in cells with a low nuclear concentration of β-catenin. The mechanism of Lbx2 function we propose, based on the in vitro and in vivo gain-of-function experiments described above, predicts that the interaction between TCF and its co-repressor Gro should be stronger in embryos lacking Lbx2 activity. We therefore hypothesized that providing to the embryo an appropriate amount of a Gro-insensitive form of TCF (TCF7L1ΔGroBD) should rescue the Lbx2 loss of function phenotype.

To test this hypothesis, we first determined the maximal quantity of mRNA coding for TCF7L1ΔGroBD that can be injected into the embryo without inducing a gain-of-function phenotype of the zygotic Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway, and we found that 150 pg of TCF7L1ΔGroBD mRNA does not result in a posteriorization of the embryo. Co-injection of this amount of TCF7L1ΔGroBD mRNA into an lbx2 morphant significantly rescues the dorsalization phenotype of lbx2 loss of function, which is characterized by a strong lateral and ventral extensions of chordin expression at the gastrula stage (Fig. 5c) and by a decrease or loss of expression of the ventral and lateral markers eve1 (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and sizzled (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Finally, our model predicts that the enhanced interaction between Gro and TCF in the lateral and ventral mesoderms of lbx2 morphant can be rescued by an increased amount of β-catenin translocating into the nuclei. According to this prediction, treatment of lbx2 morphant embryos with Bio, a GSK3β inhibitor that results in the stabilization of β-catenin and its subsequent increase in nuclear translocation, should rescue the Lbx2 dorsalization phenotype characterized by the expression of chordin in ventral and lateral mesoderms; indeed, this is what we observe (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In addition, this treatment restores, in the lateral and ventral posterior mesoderms of lbx2 morphant embryos, the expression of fibronectin 1b (fn1b), a direct target of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway20, the expression of which is almost abolished in the absence of Lbx2 (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

These rescues of lbx2 loss-of-function phenotypes by expression of a Gro-insensitive TCF7L1 transcription factor or by an increased amount of nuclear β-catenin demonstrate that Lbx2 acts through the modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional response in the posterior ventral and lateral mesoderms at the gastrula stage (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

As an additional support for this interpretation, we found that loss of function of Gro, through Gro1 and Gro2 double MO-KD, sensitizes the gain of function of Lbx2. Loss of function by MO-KD of Gro1 (transducin-like enhancer of split 3b, tle3b)21, of Gro2 (transducin-like enhancer of split 3a, tle3a)22 as well as double Gro1–Gro2 MO-KD (Fig. 5a) have no effect on early embryonic development. This is likely because of the presence of large amounts of maternally provided products of these two genes23. However, while a weak gain of function of Lbx2 (injection of 15 pg Lbx2 mRNA) has little effect in WT embryos, this effect is strongly enhanced in Gro1–Gro2 double morphants (Fig. 5a).

Discussion

Taken together, our data demonstrate that, in the absence of Lbx2, Wnt/β-catenin signalling is strongly attenuated because of an increased interaction between the co-repressor Gro and TCF (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Conversely, overexpression of Lbx2 attenuates the interaction between TCF and Gro allowing a lower concentration of nuclear β-catenin to initiate transcription of Wnt target genes. This explains why, in embryos overexpressing Lbx2, the sp5l expression territory extends towards the animal pole, further away from the source of its inducer, Wnt8a (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). This mechanism of Lbx2 regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway differs from the mechanism proposed for another transcription factor, Engrailed-1, that also contains an eh1 motif and is able to bind to Gro but has been shown to negatively regulate the β-catenin signalling in a Gro-independent manner24.

In a previous model of the transcriptional regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway7, the activation of target gene expression was described as resulting from the binding of β-catenin to the amino-terminal domain of TCF proteins and the displacement of the co-repressor Gro/TLE4,5,25. The resulting TCF-β-catenin complex then recruits transactivator proteins and activates transcription of target genes.

More recently, another model emerged that suggests, at least for TCF7L1, a slightly different mechanism involving the removal of the TCF7L1-Gro/TLE complex from the promoter. This would allow binding of the promoter by activating complexes of TCFs, β-catenin and associated chromatin-remodelling factors that generate an open chromatin state promoting transcription of Wnt target genes26,27. In this model, Gro is not simply displaced by β-catenin but the whole TCF7L1-Gro/TLE repressor complex is replaced by an activator complex containing another TCF (such as lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (LEF1) or TCF7)27 associated to β-catenin. In agreement with this model, we found that the phenotype linked to the upregulation of the zygotic canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in morphants for the repressor TCFs (TCF7L1; TCF7L2) cannot be rescued by Lbx2 loss of function (Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating that activator TCFs (TCF7; LEF) still present in morphant embryos are insensitive to the lack of Lbx2 and to the associated increase in amount of free Gro co-repressors.

In both models, however, Wnt-responsive elements associated with repressor complexes (that promote compaction of chromatin when the pathway is not activated) become associated with activator complexes (that promote opening of compacted chromatin when the stimulation of the pathway results in nuclear translocation of β-catenin).

In the absence of stimulation by a Wnt ligand, the transcription of target genes is actively repressed by the TCF7L1-Gro/TLE complex. Therefore, every condition preventing or diminishing the amount of repressor complex results in an activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. This is the case for a mutant of TCF7L1 (headless) in the zebrafish28 or for knockdown of this gene in the mouse26. Both result in the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by preventing formation of functional TCF7L1-Gro/TLE repressor complexes at the level of the DNA-binding partner, TCF7L1. This is also the case when binding of the co-repressor Gro/TLE to TCF is prevented by removing the domain of TCF7L1 responsible for binding Gro/TLE. This deletion has been shown to eliminate the repressive function of TCF7L1 and to increase transcription of target genes29,30,31. Of course, this is also true when the Wnt/β-catenin signalling is activated by Wnt ligands as nuclear import of β-catenin and post-translational modification of TCF7L1-Gro/TLE result in the activation of transcription through the clearance of TCF7L1-Gro/TLE repressor complexes associated with Wnt-responsive elements27. Finally, sequestration of Gro by Lbx2, which reduces the amount of Gro bound to TCF7L1 and hence the amount of repressor activity, also results in the expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Conversely, knockdown of Lbx2 protein leads to an increase, in the ventral and lateral mesoderms, of the amount of Gro able to bind to TCF7L1 forming functional repressor complexes, thereby preventing the transcriptional activation of Wnt/β-catenin target genes normally expressed in these territories (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

Altogether, these genetic and experimental conditions demonstrate that the switch from repression to activation of transcription of Wnt/β-catenin target genes is regulated by the amount of functional TCF7L1-Gro/TLE repressor complex. This is achieved either through the removal of the repressive TCF7L1-Gro/TLE complex from the promoter or through the regulation of the amount of Gro/TLE that is able to bind to TCF7L1 to form an active repressor complex.

In conclusion, the mechanism by which the transcription factor Lbx2 modulates Wnt/β-catenin signalling during early embryonic development shows that the regulation of the Wnt pathway is not restricted to the well-characterized control of the balance between degradation and stabilization/nuclear translocation of β-catenin and that the level of co-repression of TCF by Gro proteins is also tightly controlled. In this context, Lbx2, in the posterior ventral and lateral mesoderms (that is, in territories adjacent to the source of canonical Wnt ligands from the gastrula stage to early somitogenesis), promotes the transcription of Wnt/β-catenin target genes through the attenuation of the Gro/TLE co-repression activity. This allows for the modulation, in a tissue-specific manner, of the cellular response to a given amount of Wnt ligand by promoting the expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes in cells expressing Lbx2. This mechanism of regulation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin described here for events occuring at early developmental stages may also be utilized later in development as a way to modulate the cellular response to Wnt stimulation. In support of this, we found that lbx2 expression territories are always overlapping and/or adjacent to expression territories of genes coding for canonical Wnts (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Methods

Zebrafish strain and husbandry

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) used in this study are hybrids generated from crosses between two wild-type strains, AB × Tu. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all steps were taken to minimize animal discomfort. The University of Virginia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols.

Morpholino sequences and injections

MOs have been injected as described32. Briefly, morpholinos (Gene Tools) were resuspended in water as a 4-mM stock solution and diluted in 0.2% PhenolRed and 0.1 M KCl before use to the appropriate concentration. Embryos were dechorionated at the one-cell stage using Pronase E and injected with 1 nl of morpholinos solution, using an Eppendorf 5426 microinjector.

Because Lbx2 MOs induce nonspecific necrosis at late developmental stages, they have been co-injected with morpholinos against p53 to limit this side effect33.

The sequence of the morpholinos used is: lbx2-MO1: TAGAGCTGGAGGTCATCTCAGTCCC (translation-blocking MO covering the translation initiation start, underlined); lbx2 MO2: CGACAGAAGTCACCTAGCTCGCTC (translation-blocking MO complementary to 5′ untranslated repeat sequence); lbx2 MO-SA: TGTGTTCACGACCTTAAAATGGAAA (splice-blocking morpholino targeting the splice acceptor site of the Lbx2 intron); lbx2 MO-SD: GCGTTGATGTGTTCACGACCTTAAA (splice-blocking morpholino targeting the splice donor site of the Lbx2 intron). Loss-of-function phenotypes obtained upon injection of these four different MOs are similar but with a lower penetrance for splice-blocking MOs. Injection of a combination of the two splice-blocking MOs results in a dorsalization phenotype identical to that resulting from injection of translation-blocking MOs.

p53 MO: GCGCCATTGCTTTGCAAGAATTG 33,wnt8a MO1: ACGCAAAAATCTGGCAAGGGTTCAT 12,

wnt8a MO2: GCCCAACGGAAGAAGTAAGCCATTA 12,

gro1 (tle3b) MO: CGGCCCTGCGGATACATCTTGAATG 34,

gro2 (tle3a) MO: ATGTATCCTTTATTTATTGGAGCTC 22,

tcf7l1a MO: CTCCGTTTAACTGAGGCATGTTGGC 35,

tcf7l1b MO: CGCCTCCGTTAAGCTGCGGCATGTT 35 and

tcf7l2 MO: AGCTGCGGCATTTTTCCCGAGGAGC 36 have been described previously.

For all experiments, MO or combinations of MOs have been injected in more than 50 embryos and experiments have been reproduced at least three times. Amount of MO injected per embryo: lbx2 MOs: 4–6 ng, p53 MO: 4 ng, wnt8a MOs: 1 ng, gro1 MO: 3 ng, gro2 MO: 3 ng, tcf7l1a: 1 ng, tcf7l1b: 1 ng, tcf7l2: 4 ng.

The Lbx2 translation-blocking MO1 can prevent translation of an mRNA coding for a Lbx2-eGFP fusion protein but not from an mRNA coding for a Lbx2-eGFP fusion protein in which six mismatches have been introduced in the sequence targeted by the MO (Supplementary Fig. 8a–d). This establishes the efficiency and specificity of this MO. The specificity of this MO has been further demonstrated in a rescue experiment in which the dorsalization phenotype resulting from the injection of 4 ng of Lbx2-MO1 has been rescued by co-injection of 6 ng of mRNA coding for Lbx2 (an amount of mRNA that does not induce a Lbx2 gain-of-function phenotype when injected into a wild-type embryo) and in which six substitutions have been introduced in the target sequence of Lbx2-MO1 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Finally, efficiency of the splice-blocking MOs has been established using reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT–PCR) of morphant embryos (Supplementary Fig. 8e). A maternal Lbx2 mRNA is present at cleavage and early blastula stages. Zygotic transcripts can be detected starting at the shield stage. By the mid-gastrula stage, in embryos injected with a combination of Lbx2-MO-SA and Lbx2-MO-SD, all Lbx2 transcripts retain the intron establishing that injection of the combination of both splice-blocking MOs results in a complete loss of function of lbx2 gene function.

Previous reports using different translation-blocking and splice-blocking Lbx2 MOs11,37,38 have described various loss-of-function phenotypes. However, in these studies, the inhibition of Lbx2 gene function was only partial with the injection of 2.75 ng38 and 2.5 ng11 of translation-blocking MO that allowed the embryos to develop to late stages. In addition, the splice-blocking MOs that were used only partially inhibited the splicing of the Lbx2 intron11.

mRNA synthesis and injections

For mRNA synthesis, full-length, mutated or truncated cDNAs have been cloned in a pCS2+ vector, subsequently linearized with NotI and transcribed using SP6 RNA polymerase using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit from Ambion and injected as described previously32. All injection experiments have been performed on more than 50 embryos and reproduced at least three times.

The sequence that contains the Groucho-binding domain of TCF7L1, which has been deleted in the construct TCF7L1ΔGroBD, is the same as previously described5.

The Lbx2 mu-eh1 construct corresponds to the replacement of the FSIEDIL peptide sequence in the Lbx2 eh1 domain by ICLQEFI.

Cryosection and β-catenin immunostaining

Embryos injected with either Wnt8a or Lbx2 MOs or mRNAs were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 4% paraformaldehyde/1 × PBS. Fixed embryos were transferred into 30% sucrose/PBS, incubated 1 day at 4 °C, mounted in mounting medium (Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound, Sakura) and then cryosectioned. Cryosections of 40-μm thickness were used for immunostaining.

β-catenin immunostaining, using cryosections or whole embryos, was performed as described previously39 using a 1/4,000 dilution of the anti-β-catenin mouse monoclonal antibody clone 15B8 (Sigma).

In situ hybridization

PCR-amplified sequences of genes of interest were used as templates for the synthesis of an antisense RNA probe, labelled with digoxigenin-linked nucleotides. Embryos were fixed and permeabilized before being soaked in the digoxigenin-labelled probes. After washing away nonhybridized probes, digoxygenin-labelled hybrids were detected by immunohistochemistry using an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody against digoxigenin and a chromogenic substrate. The detailed protocol for in situ hybridizations on whole-mount zebrafish embryos used in this study has been described previously40.

Luciferase assay

Topflash construct (100 pg ) and Renilla reporter (10 pg) were mixed and co-injected into one-cell stage embryos with the indicated mRNA and/or MO. Embryos were allowed to develop until the bud stage, lysed in passive lysis buffer (Dual-Luciferase(R) Reporter Assay System, Promega) and the luciferase activity measured as described41. TopFlash assays were performed in triplicate for each sample. The mean value and s.d. were calculated. Error bars indicate s.d. Student’s t-test was used to assess the statistical significance.

Immunoprecipitation and in vitro binding experiments

For immunoprecipitation assays, the different full-length and truncated cDNAs have been cloned in pCMV-Tag2 (N-terminal Flag tag) or in pCMV-Tag3 (N-terminal Myc tag) vectors. The clone HA-TCF7L1 was generated in a pCS2+ vector by addition of a HA tag at the N-terminal end of the transcription factor 7-like 1a (tcf7l1, headless, formerly named tcf3)42.

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated constructs using JetPei reagent (Polyplus-transfection). Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 1 × Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche)). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described previously43 except that the lysis buffer was used as the washing buffer.

Briefly, the myc- or flag-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using agarose-conjugated anti-myc (SC-40 AC, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or Anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (A 2220, Sigma). For immunoblotting, peroxidase-conjugated antibodies against HA tag (Roche), flag tag (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and myc tag (Sigma-Aldrich) were used, respectively.

BIO treatment

A 100-mM stock solution of (2′Z,3′E)-6-Bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (TOCRIS Cat. No. 3194) was prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in 0.3 × Danieau buffer to a final concentration of 5 mM. WT or lbx2 morphant embryos were placed in 5 mM BIO solution during 1 h starting at the shield stage (6 hpf), then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and processed for in situ hybridization. Embryos in 0.3 × Danieau buffer containing DMSO carrier alone were used as controls for all experiments.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Lu, F.-I. et al. Tissue-specific derepression of TCF/LEF controls the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Nat. Commun. 5:5368 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6368 (2014).

References

Klaus, A. & Birchmeier, W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 387–398 (2008).

Huang, H. & He, X. Wnt/β-catenin signaling: new (and old) players and new insights. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 119–125 (2008).

MacDonald, B. T., Tamai, K. & He, X. Wnt/β-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 17, 9–26 (2009).

Cavallo, R. A. et al. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 395, 604–608 (1998).

Roose, J. et al. The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf-3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature 395, 608–612 (1998).

Jennings, B. H. & Ish-Horowicz, D. The Groucho/TLE/Grg family of transcriptional co-repressors. Genome Biol. 9, 205 (2008).

Cadigan, K. M. TCFs and Wnt/β-catenin signaling: more than one way to throw the switch. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 98, 1–34 (2012).

Chen, G., Fernandez, J., Mische, S. & Courey, A. J. A functional interaction between the histone deacetylase Rpd3 and the corepressor groucho in Drosophila development. Genes Dev. 13, 2218–2230 (1999).

Mosimann, C., Hausmann, G. & Basler, K. β-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 276–286 (2009).

Wotton, K. R., Weierud, F. K., Dietrich, S. & Lewis, K. E. Comparative genomics of Lbx loci reveals conservation of identical Lbx ohnologs in bony vertebrates. BMC. Evol. Biol. 8, 171 (2008).

Ochi, H. & Westerfield, M. Lbx2 regulates formation of myofibrils. BMC. Dev. Biol. 9, 13 (2009).

Lekven, A. C., Thorpe, C. J., Waxman, J. S. & Moon, R. T. Zebrafish wnt8 encodes two wnt8 proteins on a bicistronic transcript and is required for mesoderm and neurectoderm patterning. Dev. Cell 1, 103–114 (2001).

Weidinger, G., Thorpe, C. J., Wuennenberg-Stapleton, K., Ngai, J. & Moon, R. T. The Sp1-related transcription factors sp5 and sp5-like act downstream of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesoderm and neuroectoderm patterning. Curr. Biol. 15, 489–500 (2005).

Kelly, G. M., Greenstein, P., Erezyilmaz, D. F. & Moon, R. T. Zebrafish wnt8 and wnt8b share a common activity but are involved in distinct developmental pathways. Development 121, 1787–1799 (1995).

Korinek, V. et al. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a β-catenin-Tcf complex in APC-/- colon carcinoma. Science 275, 1784–1787 (1997).

Tolkunova, E. N., Fujioka, M., Kobayashi, M., Deka, D. & Jaynes, J. B. Two distinct types of repression domain in engrailed: one interacts with the groucho corepressor and is preferentially active on integrated target genes. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 2804–2814 (1998).

Brantjes, H., Roose, J., van De Wetering, M. & Clevers, H. All Tcf HMG box transcription factors interact with Groucho-related co-repressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1410–1419 (2001).

Wülbeck, C. & Campos-Ortega, J. A. Two zebrafish homologues of the Drosophila neurogenic gene groucho and their pattern of transciption during early embryogenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 207, 156–166 (1997).

Gill, G. & Ptashne, M. Negative effect of the transcriptional activator GAL4. Nature 334, 721–724 (1988).

Gradl, D., Kuhl, M. & Wedlich, D. The Wnt/Wg signal transducer β-catenin controls fibronectin expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 5576–5587 (1999).

Dayyani, F. et al. Loss of TLE1 and TLE4 from the del(9q) commonly deleted region in AML cooperates with AML1-ETO to affect myeloid cell proliferation and survival. Blood 111, 4338–4347 (2008).

Rai, K. et al. DNA demethylase activity maintains intestinal cells in an undifferentiated state following loss of APC. Cell 142, 930–942 (2010).

Wülbeck & Campos-Ortega. Two zebrafish homologues of the Drosophila neurogenic gene groucho and their pattern of transciption during early embryogenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 207, 156–166 (1997).

Bachar-Dahan, L., Goltzmann, J., Yaniv, A. & Gazit, A. Engrailed-1 negatively regulates β-catenin transcriptional activity by destabilizing β-catenin via a glycogen synthase kinase-3β-independent pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2572–2580 (2006).

Daniels, D. L. & Weis, W. I. β-catenin directly displaces Groucho/TLE repressors from Tcf/Lef in Wnt-mediated transcription activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 364–371 (2005).

Shy, B. R. et al. Regulation of Tcf7l1 DNA binding and protein stability as principal mechanisms of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cell Rep. 4, 1–9 (2013).

Chodaparambil, J. V. et al. Molecular functions of the TLE tetramerization domain in Wnt target gene repression. EMBO J. 33, 719–731 (2014).

Kim, C. H. et al. Repressor activity of Headless/Tcf3 is essential for vertebrate head formation. Nature 407, 913–916 (2000).

Pereira, L., Yi, F. & Merrill, B. J. Repression of Nanog gene transcription by Tcf3 limits embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 7479–7491 (2006).

Tam, W. L. et al. T-cell factor 3 regulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal by the transcriptional control of multiple lineage pathways. Stem Cells 26, 2019–2031 (2008).

Nguyen, H. et al. Tcf3 and Tcf4 are essential for long-term homeostasis of skin epithelia. Nat. Genet. 41, 1068–1075 (2009).

Dal-Pra, S., Furthauer, M., Van-Celst, J., Thisse, B. & Thisse, C. Noggin1 and Follistatin-like2 function redundantly to Chordin to antagonize BMP activity. Dev. Biol. 298, 514–526 (2006).

Robu, M. E. et al. p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 3, e78 (2007).

Scholpp, S. et al. Her6 regulates the neurogenetic gradient and neuronal identity in the thalamus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19895–19900 (2009).

Dorsky, R. I., Itoh, M., Moon, R. T. & Chitnis, A. Two tcf3 genes cooperate to pattern the zebrafish brain. Development 130, 1937–1947 (2003).

Meier, N. et al. Novel binding partners of Ldb1 are required for haematopoietic development. Development 133, 4913–4923 (2006).

Chen, X., Lou, Q., He, J. & Yin, Z. Role of zebrafish lbx2 in embryonic lateral line development. PLoS ONE 6, e29515 (2011).

Lou, Q., He, J., Hu, L. & Yin, Z. Role of lbx2 in the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway for convergence and extension movements and hypaxial myogenesis in zebrafish. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1024–1032 (2012).

Lyman Gingerich, J., Westfall, T. A., Slusarski, D. C. & Pelegri, F. hecate, a zebrafish maternal effect gene, affects dorsal organizer induction and intracellular calcium transient frequency. Dev. Biol. 286, 427–439 (2005).

Thisse, C. & Thisse, B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 3, 59–69 (2008).

Sun, Z. et al. Activation and roles of ALK4/ALK7-mediated maternal TGFβ signals in zebrafish embryo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345, 694–703 (2006).

Pelegri, F. & Maischein, H. M. Function of zebrafish beta-catenin and TCF-3 in dorsoventral patterning. Mech. Dev. 77, 63–74 (1998).

Zhang, L. et al. Zebrafish Dpr2 inhibits mesoderm induction by promoting degradation of nodal receptors. Science 306, 114–117 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Guillaume Junion for his participation in the initial phase of the project and Krzysztof Jagla for discussion and advice. We thank R.A. Bloodgood for his careful reading of the manuscript and R.T. Moon and A. Meng for providing constructs. We thank S. Vecchio and K. Li for taking care of the fish. This work was supported by funds from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the EU 6th Framework programme (MYORES) and the University of Virginia. Y.-H.S. was supported by the Fondation franco-chinoise pour la science et ses applications, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31222052), the National 973 project of China (2010CB126306) and the Institute of Hydrobiology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.-I.L., Y.-H.S. and C.-Y.W. carried out the experiments. C.T. and B.T. designed the project. F.-I.L., Y.-H.S., C.-Y.W., C.T. and B.T. analysed the data. F.-I.L., B.T. and C.T. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-9 (PDF 4120 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, FI., Sun, YH., Wei, CY. et al. Tissue-specific derepression of TCF/LEF controls the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Nat Commun 5, 5368 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6368

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6368

This article is cited by

-

The malignancy suppression and ferroptosis facilitation of BCL6 in gastric cancer mediated by FZD7 repression are strengthened by RNF180/RhoC pathway

Cell & Bioscience (2023)

-

Extracts of Qizhu decoction inhibit hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in C57BL/6 mice by suppressing NF-κB signaling

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

MiR-452 promotes an aggressive colorectal cancer phenotype by regulating a Wnt/β-catenin positive feedback loop

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2018)

-

Lysosomal activity maintains glycolysis and cyclin E1 expression by mediating Ad4BP/SF-1 stability for proper steroidogenic cell growth

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

MicroRNA-224 sustains Wnt/β-catenin signaling and promotes aggressive phenotype of colorectal cancer

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.