Abstract

The applicability of Fourier’s law to heat transfer problems relies on the assumption that heat carriers have mean free paths smaller than important length scales of the temperature profile. This assumption is not generally valid in nanoscale thermal transport problems where spacing between boundaries is small (<1 μm), and temperature gradients vary rapidly in space. Here we study the limits to Fourier theory for analysing three-dimensional heat transfer problems in systems with an interface. We characterize the relationship between the failure of Fourier theory, phonon mean free paths, important length scales of the temperature profile and interfacial-phonon scattering by time-domain thermoreflectance experiments on Si, Si0.99Ge0.01, boron-doped Si and MgO crystals. The failure of Fourier theory causes anisotropic thermal transport. In situations where Fourier theory fails, a simple radiative boundary condition on the heat diffusion equation cannot adequately describe interfacial thermal transport.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When heat carriers have mean free paths (MFP) shorter than important length scales of the temperature profile, heat transport is diffusive. When heat carriers have MFPs comparable to, or larger than, important length scales of the temperature profile, heat transport is ballistic. In nonmetals, the dominant heat carriers are phonons that have a broad spectrum of MFPs and frequencies1,2. As a result, no single length scale describes the transition from diffusive to ballistic thermal transport. Instead, as length scales in a thermal transport problem decrease, Fourier theory has diminishing predictive power3,4,5,6,7.

The breakdown of Fourier theory at small length scales has implications for nanoelectronics8 and nanostructured thermoelectric devices9 and has received a great deal of recent attention1,2,3,4,5,6,7,10,11,12,13,14. For example, deviations between Fourier theory predictions and experimental data have been reported to depend on (1) the width of the nickel heater lines in nanofabricated Ni/sapphire samples7, (2) the diameter of the heating pump laser beam, 2w0, in time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) measurements of bulk Si between 30 and 100 K (ref. 4, 3) the spatial frequency of heating in thermal grating measurements of 400 nm thick Si membranes at 300 K (ref. 10) and (4) the frequency of periodic heating, f, in TDTR measurements of semiconductor alloys and some types of amorphous silicon between 80 and 420 K (refs 6, 15). In TDTR, and the related technique of frequency-domain thermoreflectance (FDTR), f sets the time interval over which heat travels and, therefore, controls an important length scale of the temperature profile. When heat flow is diffusive, this length scale is known as the thermal penetration depth, dp=(Λ/πCf)1/2, where Λ is the thermal conductivity and C is the volumetric heat capacity.

These experiments have greatly advanced understanding of thermal transport on nanometer to micron length scales. However, unresolved issues preclude a complete picture of when and how Fourier theory will fail in a nanoscale thermal transport problem. For example, why do deviations between TDTR data and Fourier theory predictions sometimes depend on f but not w0 (ref. 6), and other times on w0 but not on f (ref. 4)?

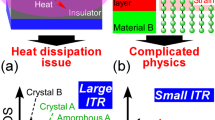

All prior TDTR and FDTR studies have interpreted data that deviates from Fourier theory predictions as phenomena intrinsic to the phonon dynamics of the material being studied and have neglected the role of the interface. TDTR and FDTR experiments require samples to be coated with a thin metal film to serve as an optical transducer, introducing a metal/sample interface to the heat transfer problem. The interface causes a thermal resistance due to the reflection/transmission of phonons, that is, interfacial-phonon scattering16. This thermal resistance is typically described with a radiative boundary condition on the heat diffusion equation, known as the interfacial thermal conductance17. This description implicitly assumes the temperature is well defined at each side of the interface and that all phonons in the solid are in equilibrium with each other at all distances from the interface. Whether this assumption is justified in nanoscale thermal transport problems has long been controversial18, but it is particularly suspect in experiments where a significant fraction of heat-carrying phonons are ballistic. Despite this, experiments that cannot be explained using a radiative boundary condition for heat transfer at the interface are rare5.

Here, we report the results of three sets of experiments that examine how the failure of Fourier theory in TDTR experiments relates to the MFP distributions in solids and the transport properties of the metal/sample interface. In our first set of experiments, we perform TDTR measurements of Si at room temperature with offset pump and probe beams, allowing for the independent determination of the through-plane and in-plane thermal conductivities19. The beam-offset measurements demonstrate that varying w0 in a TDTR experiment more strongly affects the applicability of Fourier theory in the in-plane direction. In our second set of experiments, we perform TDTR measurements of Si, Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si heavily doped with boron (Si:B) as a function of w0, f and temperature. The Ge in Si0.99Ge0.01 preferentially scatters high-frequency phonons due to mass disorder20, while the boron in Si:B preferentially scatters low-frequency phonons due to hole/phonon scattering21. As a result, the MFP distributions are systematically different in Si, Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si:B, allowing us to relate differences in the phonon dynamics to differences in how Fourier theory fails. We posit that the thermal diffusivity of high-wavevector phonons determines whether a failure of Fourier theory is observable in TDTR experiments as a function of f or w0. In materials whose high-wavevector phonons have a low thermal diffusivity, Fourier theory fails more readily as a function of f than w0. In materials whose high-wavevector phonons have high thermal diffusivity, Fourier theory fails as a function of w0. In our third set of experiments, we show treating interface transport with a radiative boundary condition on the heat diffusion equation can be an inadequate description when length scales of the temperature profile are comparable to phonon MFPs.

A secondary goal of our work is to describe a ballistic/diffusive thermal model capable of explaining (1) why the failure of Fourier theory is anisotropic and (2) how interfacial-phonon scattering impacts the accuracy of Fourier theory predictions. Fourier theory fails in TDTR experiments because Fourier’s law is unable to predict the heat current, J, due to long MFP phonons near temperature-profile minima and maxima (extrema). Fourier’s law fails near temperature-profile extrema because it uses a first-order Taylor-series approximation for the temperature profile that is particularly inaccurate in proximity to locations where ∇T changes sign.

Results

Anisotropic failure of Fourier theory in Si

For TDTR measurements of Si at room temperature with w0<5 μm, we observe discrepancies between Fourier theory predictions and experimental data22, see Fig. 1. From our TDTR data, we derive an apparent thermal conductivity, ΛA, and an apparent interface conductance, GA, for each measurement by fitting the data with an isotropic diffusive model19,23 that treats the Λ of Si, and interfacial thermal conductance between Al and Si, G, as fitting parameters. GA is the value for G that produces the best fit to the shape of decay of Tin with pump-probe delay time, tD. ΛA is the value for Λ that produces the best fit to the out-of-phase temperature response, Tout.

(a) Amplitude of measured in-phase and out-of-phase temperature response of 80 nm Al/Si at room temperature as a function of pump/probe delay time with w0=1.05 and 10.3 μm (circles), and the prediction of an isotropic diffusive model with bulk thermal properties for Si and an Al/Si interface conductance of GA=250 MW m−2 K−1 (lines). Bulk thermal properties for Si cannot explain the magnitude of Tout at w0=1.05 μm; a thermal conductivity of ΛA=105 W m−1 K−1 is required to explain the data with an isotropic diffusive model (b) Amplitude of the measured out-of-phase temperature response at −100 ps delay time and w0=1.05 μm, as function of offset distance between pump and probe beam centres. An anisotropic diffusive thermal model with Λr=80 and Λz=140 W m−1 K−1 (red curve) is in good agreement with the data, while an isotropic value of ΛA=105 W m−1 K−1 (blue curve) over-predicts the amplitude of temperature oscillations away from the centre of the pump beam.

Beam-offset measurements, see Fig. 1b, suggest that Fourier theory over-predicts the thermal response of Si for a measurement with w0≈1.05 μm and f=9.8 MHz because Fourier theory over-predicts the in-plane component of the heat current, Jr. In other words, the solution of the heat diffusion equation with an isotropic thermal conductivity of ΛA=105 W m−1 K−1 over-predicts the amplitude of the thermal response away from the centre of the pump beam. If we instead fit the data with an anisotropic model19 that treats the through-plane and in-plane thermal conductivities, Λz and Λr, as independent fitting parameters, we find Λz≈140 W m−1 K−1 and Λr≈80 W m−1 K−1. The heat current has two directional components, through-plane and in-plane; therefore, we can only define apparent thermal conductivities for these directions. Adding additional fitting parameters cannot improve the fit because the fit is already excellent.

That Fourier theory fails anisotropically helps resolve how prior TDTR studies of Fourier theory failure relate to each other. Prior studies that observed a dependence of ΛA on f studied low Λ materials, such as semiconductor alloys and a-Si (refs 6, 15). These TDTR measurements observed a failure of Fourier theory in the through-plane direction because dp≪w0, meaning the in-plane heat current was negligible. On the other hand, the observation of Minnich et al.4 that ΛA of Si depends on w0 below 100 K was related to a failure of Fourier theory in the in-plane direction. That Fourier theory fails anisotropically has direct implications for the interpretations of prior experiments that assumed Fourier theory failed isotropically in three-dimensional heat-transfer problems1,4,7,24, see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2.

Failure of fourier theory in Si, Si:B and Si0.99Ge0.01

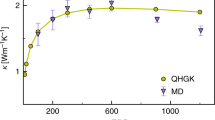

Comparisons between measurements of Si, Si:B and Si0.99Ge0.01 allows us to study how Fourier theory failure in TDTR experiments relate to differences in MFP distributions because hole/phonon and point-defect/phonon scattering produce controlled differences in the MFP distributions of these materials21. We quantify the impact of hole/phonon and point-defect/phonon scattering on the Λ of Si with thermal conductivity relaxation time approximation (RTA) models for Si, Si:B and Si0.99Ge0.01 (see Supplementary Methods).25 By RTA, we mean that we assume all scattering can be combined into a single frequency-dependent relaxation-time using Matthiessen’s rule, ignoring that normal phonon/phonon scattering is not resistive in isolation from other scattering mechanisms26. Our RTA models compare favourably to first-principles calculations20,27,28, see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3.

Relaxation time approximation model predictions for the thermal properties of Si, Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si:B at room temperature (Supplementary Equation 2). (a) Thermal conductivity accumulation functions, α. First-principles results from ref. 27 and ref. 28 for Si are included for comparison (green dashed and solid lines). (b) Spectral distribution of the heat capacity. (c) Spectral distribution of the thermal conductivity.

The RTA model results for Si, Si:B and Si0.99Ge0.01 are shown in Fig. 2 three ways: the thermal conductivity accumulation function, the heat capacity spectral distribution and the thermal conductivity spectral distribution. The thermal conductivity accumulation function is the cumulative contribution to the heat current from phonons with a MFP less than L (ref. 2),

where j sums over all three polarization branches, ΛB is the bulk thermal conductivity, ℓ is the MFP and v is the group velocity. The heat-capacity spectral distribution is

where kB is Boltzmann’s constant, D(q) is the density of states and n(q) is the occupation number. The thermal conductivity spectral distribution, λ(q), quantifies the heat carried by phonons with wavevector q,

where τ(q) is the relaxation time.

In our discussion below, we refer to differences in λ(q) for high- and low-wavevector phonons in different materials. We define high-/low-wavevector phonons as those with a q larger/smaller than q0≈0.4qmax in Si and Si:B and q0≈0.25qmax in Si0.99Ge0.01. This definition of q0 is chosen so that ℓ(q0) at room temperature is less than dp(20 MHz)/5 so that all high-wavevector phonons have MFPs much shorter than the minimum length scales of the temperature profile. This definition for high-/low-wavevector phonons leaves the majority of the total heat capacity (>90%) with high-wavevector diffusive phonons (Fig. 2b), meaning the mean occupation of the high-wavevector phonons defines the temperature profile of the solid. We choose to frame our discussion in terms of high-/low-wavevector phonons instead of short/long MFPs because several of our conclusions are based on comparing results for materials with controlled differences in λ(q<q0) and λ(q>q0).

At room temperature, Fourier theory accurately predicts the thermal response of Si and Si:B up to f=17.6 MHz, but inaccurately predicts the thermal response of Si0.99Ge0.01, see Fig. 3a. (Fig. 3a also includes measurements of ΛA(f) for Si0.2Ge0.8 and Ge that are relevant to results presented in the next section but are not discussed here.) Phonons with ℓ>dp (17.6 MHz) carry 50 W m−1 K−1 of heat in Si and 30 W m−1 K−1 in Si0.99Ge0.01 (Fig. 2a), making it difficult to explain the different behaviours for ΛA(f) as only a length-scale effect. The most significant difference between Si and Si0.99Ge0.01 is λ(q) for q>q0 (Fig. 2c). Therefore, we suggest a second important factor in observing a failure of Fourier theory in the through-plane direction, aside from low-wavevector phonons with MFPs longer than experimental length scales, is for high-wavevector phonons to have a small thermal conductivity,  , and therefore small thermal diffusivity.

, and therefore small thermal diffusivity.

(a) Deviations between ΛA(f) for Si, Si:B, Si0.99Ge0.01, Si0.2Ge0.8 and Ge (markers) at w0=10 μm and bulk thermal conductivity values (dashed lines). Solid lines are the predictions of a ballistic/diffusive model for thermal transport. (b) Deviations between ΛA(w0) for Si, Si:B, and Si0.99Ge0.01 at f=1.1MHz (makers) and their bulk thermal conductivity values (dashed lines). Solid lines are the predictions of a ballistic/diffusive model for thermal transport.

Prior experimental studies that observed a dependence of ΛA on f emphasized the importance of temperature profile length scales being comparable to MFPs1,6,24. As we demonstrate in more detail in subsequent sections, another factor causing ΛA to deviate from ΛB in the through-plane direction is interfacial-phonon scattering. The interfacial-phonon scattering of long MFP phonons reduces the effective thermal conductivity, Kz(z)=|Jz(z)/∇zT(z)|, of the sample near the interface, analogous to how boundary scattering reduces Λ of nanostructured materials2. (Here, we use a different symbol for thermal conductivity, K instead of Λ, to distinguish this effective property from the apparent values defined earlier.) The dependence of ΛA on f is evidence that the interfacial thermal resistance is not isolated to the interface at z=0 as is assumed in standard analysis of TDTR and FDTR experiments.

An equivalent way to consider the effect of the interface is as a boundary condition on the heat current. The spectral distribution of the heat current across the interface is proportional to v(q)c(q) (ref. 17), while the spectral distribution of the heat current in the solid is λ(q). This creates a spatial mismatch in the spectral distribution of the heat current, resulting in a nonequilibrium between high- and low-wavevector phonons near z=0. We label this effect as an interfacial nonequilibrium thermal resistance, GNE−1. GNE−1 quantifies the resistance between the high-wavevector phonons that carry the heat across the interface and the low-wavector phonons that carry the heat in the solid.

In this context, the thermal diffusivity of high-wavevector phonons affects ΛA(f) two ways. A small value for  corresponds to a larger GNE−1 (ref. 3). In addition, a small thermal diffusivity increases the measurement sensitivity to Kz near z =0, where the high- and low-wavevector phonons are not in equilibrium. The dependence of ΛA on f occurs because the sensitivity to GNE−1, which is localized near z=0, increases with increasing f and shorter dp. The predictions of a ballistic/diffusive model (described in Methods) that accounts for both shortened length scales and interfacial-phonon scattering is in reasonable agreement with our data (solid lines in Fig. 3a). In our ballistic/diffusive model, the heat current from low-wavevector phonons is calculated with a nonlocal expression that reduces to Fourier’s law if MFPs are shorter than the temperature profile length scales. The model makes no assumptions regarding how low-wavector phonon MFPs compare with temperature profile length scales. Supplementary Figure 4 shows how interfacial/phonon scattering and f control the Kz(z) predicted by our ballistic/diffusive model.

corresponds to a larger GNE−1 (ref. 3). In addition, a small thermal diffusivity increases the measurement sensitivity to Kz near z =0, where the high- and low-wavevector phonons are not in equilibrium. The dependence of ΛA on f occurs because the sensitivity to GNE−1, which is localized near z=0, increases with increasing f and shorter dp. The predictions of a ballistic/diffusive model (described in Methods) that accounts for both shortened length scales and interfacial-phonon scattering is in reasonable agreement with our data (solid lines in Fig. 3a). In our ballistic/diffusive model, the heat current from low-wavevector phonons is calculated with a nonlocal expression that reduces to Fourier’s law if MFPs are shorter than the temperature profile length scales. The model makes no assumptions regarding how low-wavector phonon MFPs compare with temperature profile length scales. Supplementary Figure 4 shows how interfacial/phonon scattering and f control the Kz(z) predicted by our ballistic/diffusive model.

At room temperature, Fourier theory does not accurately predict the thermal response of Si and Si:B for spot sizes below 5 μm, see Fig. 3b. Beam-offset measurements of Si:B and Si at f=9.8 MHz yield Λr≈74±10 W m−1 K−1 and Λr≈84±10 W m−1 K−1 at w0=1 μm, respectively. Alternatively, we can resolve no dependence of ΛA on w0 in Si0.99Ge0.01, despite ≈25 W m−1 K−1 of heat being carried by phonons with ℓ>w0 (Fig. 2a). For comparison, Si and Si:B have ≈50 and 25 W m−1 K−1 of heat carried by phonons with ℓ>w0.

The lack of a spot-size dependence for ΛA of Si0.99Ge0.01 suggests a second condition for an observable failure of Fourier theory in the in-plane direction, aside from low-wavevector phonons having ℓ>w0, is for high-wavevector phonons to have a large Λ0 and therefore high thermal diffusivity. TDTR measurements are more sensitive to Kr(r≈w0)=|Jr(r≈w0)/∇rT(r≈w0)| in high thermal diffusivity materials where the following condition is met: the magnitude of Jr(r≈w0) is comparable to the average magnitude of Jz across 0<z<dp. Making w0 small enough to meet this condition in low thermal diffusivity materials is challenging given diffraction constraints on w0, but we expect that ΛA for Si0.99Ge0.01 would be reduced at smaller spot size. The predictions of our ballistic/diffusive model are in reasonable agreement with our data (solid lines Fig. 3b).

The temperature dependence of λ(q) in Si, Si:B and Si0.99Ge0.01 are systematically different. Therefore, varying the ambient temperature offers another avenue for relating Fourier theory failure in TDTR experiments to λ(q). In Si, both λ(q>q0) and ℓ(q<q0) increase rapidly with decreasing temperature. In Si0.99Ge0.01, mass disorder prevents a large increase in λ(q>q0) with decreasing temperature. In Si:B, hole-phonon scattering prevents a large increase in ℓ(q<q0) with decreasing temperature.

Figure 4 shows measurements of ΛA(w0) for Si, Si:B and Si0.99Ge0.01 between 40 and 300 K. In Si, the spot-size dependence of ΛA is large, but the frequency dependence between 1 and 10 MHz is insignificant. We credit the increase in the spot-size dependence of ΛA as temperature decreases to large increases in both the thermal diffusivity of high-wavevector phonons and the MFPs of low-wavevector phonons. The longer MFPs of low-wavevector phonons increases the percentage of ballistic phonons. The increase in thermal diffusivity increases measurement sensitivity to Jr and decreases measurement sensitivity to Kz near the interface. In Si:B, ΛA is weakly dependent on w0 and has no observable f dependence because hole-phonon scattering prevents a rapid increase in ℓ(q<q0). The similarity in the temperature dependence of ΛA for Si versus Si:B supports the hypothesis that when w0 is small, Fourier theory is over predicting the heat current from long MFP phonons, as Minnich et al.4 posited.

Apparent isotropic thermal conductivity of Si (circles), Si:B (squares) and Si0.99Ge0.01 (down triangles) for w0=5, 10 and 25 μm and f=9.8 MHz, as a function of temperature. For Si0.99Ge0.01, ΛA(T) at 1.1 MHz is also shown (up triangles). Solid lines are literature values for the thermal conductivity of bulk Si and a 3-μm thick thin film of Si:B with a 1 × 1019 cm−3 doping level21,31. Dashed lines are the prediction of our RTA model for Si0.99Ge0.01, for which there are no prior low-temperature thermal conductivity measurements. The spot size used to measure ΛA is indicated by colour, red for 25 μm, black for 10 μm and blue for 5μm.

In Si0.99Ge0.01, ΛA below 100 K does not approach the prediction of the RTA model for ΛB at any w0 or f, indicating that Fourier theory is grossly inaccurate for this heat transfer problem because the majority of heat-carrying phonons have MFPs longer than temperature profile length scales. We attribute the increase in spot-size dependence of ΛA for Si0.99Ge0.01 with decreasing temperature to a rapid increase of ℓ(q<q0), along with the more slowly increasing thermal diffusivity of low-wavevector phonons.

Beam-offset measurements confirm the failure of Fourier theory is anisotropic at low temperatures. For example, fitting beam-offset data for Si at 77 K, 9.8 MHz and w0=4.7 μm yields Λz ≈900 and Λr ≈300 W m−1 K−1. Similarly, fitting beam-offset data for Si0.99Ge0.01 at 120 K, 1.1 MHz and w0=5 μm yields Λz≈50 and Λr≈30 W m−1 K−1.

Our results for ΛA of Si agree with ref. 4 if compared as a function of the root mean square of the pump and probe spot sizes, but not if compared as a function of only pump spot size. (Our pump and probe spot sizes are equal, but ref. 4 used different pump and probe spot sizes.) In a linear heat transfer problem, an exchange symmetry exists between thermometers and heaters. Therefore, the TDTR measured thermal response must by symmetric to the exchange of the pump and probe beams. The exchange symmetry between thermometers and heaters exists because a linear problem can be solved with a Green’s function solution, g(ρ,t;ρ′t′), where ρ demarks position, and Green’s functions possess the following symmetry: g(ρ,t;ρ′t′)=g(ρ′,−t′;ρ,−t) (ref. 29). That the length scale that governs ΛA includes the probe spot size is an important result, as any theoretical effort to derive MFP distributions from ΛA(w0) ignoring probe spot size is incomplete.

In addition to the experiments described above, we collected FDTR data for Si at room temperature between 1.1 and 17.6 MHz with w0=2.55 and 4.7 μm. Our FDTR data agree with the predictions of a thermal model using the ΛAand GA derived from TDTR data collected at the same w0 (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Our FDTR results therefore strongly disagree with BB-FDTR measurements of a Au/Cr/Si sample in the same frequency range1. We attribute the discrepancy to ref. 1 neglecting weak Au electron–phonon coupling in their data analysis, see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6.

Role of the interface

Standard analysis of TDTR and FDTR data treats interfacial transport with a radiative boundary condition on the heat diffusion equation, Jz(z=0)=G0ΔT(z=0), where G0 is the interface conductance of diffusive phonons17,

Here, Rj is the probability that a phonon with polarization j impinging on the interface from the sample side reflects and is believed to be determined by interfacial bonding strength, interface disorder and morphology and the vibrational properties of both the sample and metal transducer16,30. Using equation (4) assumes that the thermal resistance from interfacial/phonon scattering is localized to z=0, not spread across a finite length scale determined by phonon MFPs. This assumption is overly simplistic; interfacial/phonon scattering should affect the heat current over a length scale comparable to the MFPs of the heat-carrying phonons.

Measurements of GA for Si, Si0.99Ge0.01, Si0.2Ge0.8 and Ge crystals coated with Al after native oxide removal demonstrate that equation (4) is an inadequate description of interface transport for Al/Si0.99Ge0.01 and Al/Si0.2Ge0.8. The measurement results, shown in Fig. 5, have two features inconsistent with the description offered by equation (4): the dependence of GA on f and the significant differences between GA of Si versus Si0.99Ge0.01 and of Si0.2Ge0.8 versus Ge.

Apparent interface conductance of Si (black squares), Si0.99Ge0.01 (red circles), Si0.2Ge0.8 (green circles) and Ge (orange squares) along with the predictions of a ballistic/diffusive model (solid lines). The value of GA for Si shown here differs from the value reported in Fig. 1 because the data in Fig. 1 is for a sample that did not have the native oxide removed before Al deposition. The low thermal diffusivity of Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si0.2Ge0.8 results in a large interfacial nonequilibrium thermal resistance that effects the value of GA at low f, resulting in a lower value of GA than is observed for Si or Ge.

The dependence of GA on f for Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si0.2Ge0.8 is consistent with a reduced effective thermal conductivity of the sample, Kz=|Jz/∇zT|, near the interface due to an interfacial nonequilibrium thermal resistance, GNE−1. For each TDTR measurement, we have two pieces of data that determine GA and ΛA: the shape of decay of Tin(tD) and the magnitude of the out-of-phase thermal response, Tout (Fig. 1). The shape of the decay of Tin(tD) depends on G and  . Here, δ is the distance heat travels in 3.5 ns, the maximum delay time. Tout, which determines ΛA, depends on the average value of Kz over the distance heat travels in 1/f,

. Here, δ is the distance heat travels in 3.5 ns, the maximum delay time. Tout, which determines ΛA, depends on the average value of Kz over the distance heat travels in 1/f,  . As f increases, Tout becomes more sensitive to

. As f increases, Tout becomes more sensitive to  because dp decreases, and therefore ΛA decreases (Fig. 3). In the thermal model we use to derive ΛA and GA (ref. 23), we assume solid Λ is homogenous, that is, that

because dp decreases, and therefore ΛA decreases (Fig. 3). In the thermal model we use to derive ΛA and GA (ref. 23), we assume solid Λ is homogenous, that is, that  . If this is false, the only way the diffusive thermal model can still fit the frequency-independent shape of Tin(tD), which it must to fit the data, is for GA to depend on f. Therefore, the dependence of GA on frequency suggests an inhomogenous Kz(z). GA and ΛA that increase and decrease, respectively, with increasing frequency suggests Kz(z<δ)<ΛA and G0>GA, consistent with the ballistic/diffusive model predictions (Supplementary Fig. 4).

. If this is false, the only way the diffusive thermal model can still fit the frequency-independent shape of Tin(tD), which it must to fit the data, is for GA to depend on f. Therefore, the dependence of GA on frequency suggests an inhomogenous Kz(z). GA and ΛA that increase and decrease, respectively, with increasing frequency suggests Kz(z<δ)<ΛA and G0>GA, consistent with the ballistic/diffusive model predictions (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The large differences in the magnitude of GA for Si, Si0.99Ge0.01, Si0.2Ge0.8 and Ge are consistent with our hypothesis that a GNE−1 is related to observations of Fourier theory failure in the through-plane direction3. In most TDTR experiments, dp is much larger than the length scale of the nonequilibrium near the interface3, and therefore GNE−1 causes a reduced value of GA in addition to any reduced value of ΛA. Our ballistic/diffusive model predicts GNE−1 is largest, and therefore GA will be smallest, for materials whose high-wavevector phonons have small Λ0. This is consistent with our results: GA for Si0.2Ge0.8 is smaller than GA for either Ge or Si, GA for Si0.99Ge0.01 is smaller than GA for Si.

To summarize, we explain the difference in magnitude and convergence/divergence of GA(f) for Si versus Si0.99Ge0.01 and Ge versus Si0.2Ge0.8 with a GNE−1 whose length scale and magnitude are largely independent of f. What changes with f is measurement sensitivity. The magnitude of GNE−1 is included in the value of GA of the alloys at low f (Fig. 5), but moves to ΛA at high f (Fig. 3) because dp becomes comparable to the length scale of nonequilibrium.

Thus far, we have posited that interfacial-phonon scattering is related to observations of Fourier theory failure in the through-plane direction based on results for ΛA and GA of SiGe alloys. Now, we present another set of experiments that supports this hypothesis: measurements of ΛA for Si and MgO at low temperature with different metal transducers and interface conditions.

In Fig. 6, we show the impact of the interface on ΛA of Si at 300 K and w0=10.3 μm. For w0=10.3 μm, Jr≪Jz, and therefore ΛA≈Λz. TDTR measurements of Al/11 nm SiO2/Si and Ta/2 nm SiO2/Si show ΛA values that deviate outside our error bars from the bulk thermal conductivity value for Si of 142 W m−1 K−1 (refs 22, 31).

Deviations of ΛA from ΛB=142 W m−1 K−1 for Al/Si and Al/ 11 nm SiO2/Si (open markers), Ta/Si and Ta/2 nm SiO2/Si (filled markers) at w0=10.3 μm as a function of f. The solid and dashed lines are the predictions of a ballistic/diffusive model that assumes all low-wavevector Si phonons that impinge on the interface reflect (R=1) or transmit (R=0).

In Fig. 7, we compare the effect of the interface and spot size for Si and MgO at 48, 83 and 144 K. The magnitude of transducer dependence of ΛA for both Si and MgO at these temperatures is on the order of 100 W m−1 K−1. In MgO, this is an ~30% change, comparable to the effect of changing from a 25 to 5 μm spot size. The large transducer dependence in MgO is evidence that significant heat is carried by non-diffusive phonons, and that Ta serves as a better thermal sink for these phonons than Al does (see Supplementary Note 3).

Effect of spot size and transducer/interface on ΛA for Si and MgO at 48, 83 and 144 K. For comparison, we include the results of ref. 4 plotted as a function of the root mean square of the pump and probe spot sizes used in their experiment. In MgO, the interface has an effect on the value of ΛA comparable to that of w0.

Importance of temperature-profile extrema

Here, we use our ballistic/diffusive model, described in equations (5)–(10), , , , , of Methods, to gain insight into the anisotropic failure of Fourier theory in TDTR measurements. The predictions of the ballistic/diffusive model support our conclusions that (1) the Fourier theory failure in TDTR experiments at small spot sizes is due to an inability of Fourier’s law to accurately predict Jr and (2) Kz is lowered near the interface because of interfacial-phonon scattering.

A simple approach for determining whether Fourier theory is accurate for a given heat transfer problem is to compare the predictions of ballistic and diffusive expressions for the heat current. In Fig. 8, we compare the predictions of diffusive and ballistic expressions for the heat current (Fourier’s law and equation (9) in Methods) for the measurement of Al/Si shown in Fig. 1. For these calculations, we approximate the temperature profile by solving the heat diffusion equation using an Al/Si interface conductance of G0=250 MW m−2 K−1 and thermal conductivity of Si of ΛB=142 W m−1 K−1. This represents the expected temperature profile if Fourier theory did not fail at small w0.

(a) Amplitude of temperature oscillations predicted by the heat diffusion equation for 80 nm Al/Si sample undergoing sinusoidal surface heating at f=10 MHz and w0=1 μm. (b–d) Qualitative comparison between the first-order Taylor series approximation of the temperature profile used in Fourier’s law (red lines), −2ℓ∇T, and the temperature profile actually traversed by 2 μm MFP phonons (black lines) with the trajectories illustrated by the arrows in a. The first-order Taylor series that Fourier’s law uses (equation (8)) is a poor approximation for the temperature profile that is traversed by phonons that are (b) travelling in the in-plane direction across r=0 and (c) travelling in the through-plane direction after reflecting from the interface at z=0. (e) Average magnitude of Jr and Jz predicted by Fourier’s law for the temperature profile in a. The colour axis is normalized to the maximum value predicted by Fourier’s law, which occurs in the z direction at r=z=0 and in the r direction at z=0 and r≈w0. TDTR measurements are most sensitive to transport properties in the regions where the heat current is largest. (f,g) Ratio of the average magnitude of Jz and Jr predicted by equation (9), to the predictions of Fourier’s law for 1 μm MFP phonons. The heat current profiles shown in f assume all 1 μm MFP phonons reflect at the interface, R=1 (adiabatic limit). The heat current profiles shown in g assume 1 μm MFP phonons transmit at the interface, R=0 (radiation limit). (h) Magnitude of the heat current predicted by equation (9) relative to Fourier’s law at two representative points. The red curves are for Jr at r=1 μm and z=150 nm. The blue curves are for the Jz at r=0 and z=500 nm. These two points are selected because they are representative of how Fourier’s law over-predicts the heat current in the regions the measurement is most sensitive to the effective thermal properties. Solid lines were calculated assuming R=1 (adiabatic limit), while the dashed lines were calculated assuming R=0 (radiation limit).

Fourier’s law fails most significantly near temperature-profile extrema for three types of long MFP subpopulations of the Si phonons (Fig. 8a–d): (1) phonons travelling in opposite directions in the in-plane direction across r=0, (2) phonons travelling in opposite directions in the through-plane direction that reflect at the interface at z=0 and (3) phonons travelling in opposite directions in the through-plane direction that transmit across the interface at z=0. The first-order Taylor series approximation of the temperature-profile Fourier’s law uses is grossly inadequate for cases (1) and (2) due to the sign change of dT/dr at r=0 and dT/dz at z=0. (The plane of z=0 is a virtual extrema in the through-plane direction because reflected phonons see a mirror image of the temperature profile.) As a result, Fourier’s law over predicts the heat current from phonons described by cases (1) and (2). Fourier’s law is also inaccurate for phonons travelling in the through-plane direction that transmit at the interface, case (3). However, the under-prediction of the heat current is less than in cases (2) and (3), because this group of phonons still see a significant temperature difference,  . While Fig. 8b–d only illustrates the failure of Fourier’s law for phonons with a MFP of 2 μm at two specific positions, the illustrations in Fig. 8b–d are representative of why Fourier theory fails near temperature-profile extrema.

. While Fig. 8b–d only illustrates the failure of Fourier’s law for phonons with a MFP of 2 μm at two specific positions, the illustrations in Fig. 8b–d are representative of why Fourier theory fails near temperature-profile extrema.

The illustrations in Fig. 8 qualitatively explain why the failure of Fourier theory is anisotropic in TDTR measurements of Si even when w0 and dp are comparable. The majority of phonons with MFPs longer than the in-plane length scale traverse the hot region without scattering (Fig. 8b), meaning these phonons won’t carry significant heat. In contrast, a significant percentage of long MFP phonons, 1−R, travelling in the through-plane direction are emitted from or absorbed in the hot metal film, (Fig. 8d), and will therefore carry significant heat.

Because Fourier’s law over-predicts Jr near r=0 (Fig. 8b), and over-predicts Jz near z=0 for phonons that reflect from the interface (Fig. 8c), the failure of Fourier theory is anisotropic, spatially inhomogeneous, and depends on the probability of phonons reflecting from the interface. We show this in Fig. 8e–h by comparing the average heat current magnitude from phonons with a 1 μm MFP predicted by Fourier’s law to the predictions of our ballistic/diffusive model in the adiabatic (R=1) and radiative (R=0) limits. In Supplementary Note 4, we discuss how altering w0 and f has the dual effect of changing length scales and measurement sensitivity to nonequilibrium near extrema.

Discussion

Our ballistic/diffusive model predicts that the spectral distribution of heat carried by low-wavevector ballistic phonons, |JNL|, is not equal to λ(q<q0) within a length scale of the interface comparable to ℓ because of interfacial-phonon scattering. For sufficiently short through-plane length scales of the temperature profile, TDTR is sensitive to this region where the spectral distribution of JNL is not equal to λ(q<q0), explaining the dependence of ΛA on f in alloys.

Prior TDTR and FDTR studies have explained deviations between ΛA and ΛB by assuming phonons with MFPs longer than some experimental length scale are ballistic and do not contribute to ΛA (refs 1, 6, 11). This is equivalent to the explanation offered by our ballistic/diffusive model in the limit that TDTR is measuring Kz(z<ℓ), that is, the through-plane temperature profile length scale is less than ℓ, and the heat carried by diffusive phonons is much greater than the heat carried by ballistic phonons, |Λ0∇T|≫|JNL|, where Λ0 is the thermal conductivity of the high-wavevector diffusive phonons.

Whether the condition that |Λ0∇T|≫|JNL| is met depends on the phonon dynamics of the material being studied. The amount of heat carried by ballistic phonons in the through-plane direction near the interface, |JNL (0<z<ℓ)|, depends on the spectral distribution of c(q)v(q) for low-wavevector ballistic-phonons (see equations (9) and (10) in Methods), while Λ0 depends on λ(q) for high-wavevector diffusive phonons. For materials like Si0.2Ge0.8, where only phonons with q<0.1qmax have MFPS longer than the length scales of the temperature profile, the assumption that |Λ0∇T|≫|JNL| is reasonable since phonons with q<0.1qmax have little heat capacity (Fig. 2b). In materials such as Si, Si0.99Ge0.01 and MgO, where the majority of heat is carried by phonons with q<0.1qmax, significant deviation from Fourier theory implies phonons with a non-negligible c(q)v(q) are ballistic. Therefore, JNL may or may not be negligible depending on Λ0 and R.

Our results are relevant for efforts to use TDTR and FDTR as a MFP spectroscopy technique1,4,24. Observations of Fourier theory failure in the through-plane and in-plane direction are both sensitive to the MFP distribution of solids (Fig. 8h). In materials where a measurement of Λr is possible with laser spot sizes on the order of microns, for example, materials with a high thermal diffusivity, it will be simpler to extract information concerning MFP distributions from measurements of Λr(w0) rather than measurements of Λz because Jr is less sensitive to interface effects than Jz. That Jr is less sensitive to R than Jz can be seen in Fig. 8f–h. For example, the difference between the adiabatic and radiative limits for Jz in Fig. 8h is much larger than for Jr. That interfacial-phonon scattering impacts Jr less than Jz is analogous to boundary scattering having less impact on the in-plane Λ of a thin film than on the through-plane Λ2.

Our study provides insight into a long standing issue regarding the definition of temperature and phonon mediated heat transfer across interfaces18. The concept of an interfacial thermal conductance implies an abrupt temperature drop at crystal boundaries, which is consistent with molecular dynamics simulations that define the temperature of individual atoms with their kinetic energy. However, whether an equilibrium concept such as temperature can be rigorously defined on length scales shorter than the MFPs of heat-carrying phonons has long been controversial18. Our ballistic/diffusive framework offers insight into this dilemma. High-wavevector phonons are in thermal equilibrium with each other on short length scales, and it is primarily the occupation of high-wavevector phonons that determine the kinetic energy of atoms (Fig. 2b). Molecular dynamics simulations are measuring Geff=|Jz/ΔT|z=0, which is different from GA when GA includes a significant interfacial nonequilibrium thermal resistance, GNE−1, as is the case for SiGe alloys.

In conclusion, we performed TDTR experiments on Si, Si0.99Ge0.01, Si:B and MgO as a function of w0, f and temperature. These experiments provide three insights into how Fourier theory fails in TDTR experiments. First, in measurements with small w0, the primary effect of the small spot size is to cause a failure of Fourier theory in the in-plane direction. Second, the thermal diffusivity of high-wavevector phonons determines whether measurements can resolve a failure of Fourier theory in the in-plane or through-plane directions for f<20 MHz and w0>1 μm at room temperature. Third, an interfacial thermal conductance is not adequate in a ballistic/diffusive heat transfer problem. To accurately describe the effect of the interface on ballistic/diffusive heat transfer problems, it is necessary to consider how the reflection and transmission of phonons prevents thermal equilibrium between heat-carrying phonons near the boundary (Fig. 8c,d).

While this paper was under review, a paper was published by Ding et al.32 theoretically examining three-dimensional heat-transfer in an Al/Si sample on timescales between 1 ps and 1 ns using the Boltzmann transport equation. Their model indicates that only Jr, and not Jz, is affected by a reduced spot size, consistent with our beam-offset measurements (Fig. 1); however, their model’s prediction that interfacial scattering does not affect Jz appears inconsistent with our experimental observations that the interface plays an important role in through-plane transport (Figs 5, 6, 7).

Methods

Experiment

In TDTR, the thermal response of a sample to a train of pump pulses periodically modulated at frequency f is characterized by measuring temperature-induced changes in the intensity of a reflected probe beam23. The experimental data consists of the in-phase and out-of-phase voltages recorded by a Si photodiode connected to an RF lock-in that picks out the signal components at the pump modulation frequency f. In our implementation of TDTR, the pump and probe spot sizes are equal. Temperature oscillations that are in-phase with the pump beam, Tin, are to a good approximation the time-domain response to pulsed heating. Temperature oscillations that are out-of-phase with the pump beam, Tout, are, to a good approximation, the out-of-phase thermal response of the sample at frequency f. Since most of the sensitivity of a TDTR measurement to the thermal properties of a sample comes from Tout, 1/f is the most important timescale in our experiment. Example TDTR data is shown in Fig. 1a. The parameters ΛA and GA are convenient proxies for our data that represent how much our measurements deviate from the predictions of Fourier theory (Fig. 1a). We do not view ΛA and GA as effective thermal properties when they depend on f or w0. In other words, the solution to the heat diffusion equation with Λ=ΛA and G=GA is only an accurate description of the surface temperature, not the entire temperature profile. Further details of our technique can be found in refs 19, 23 and 33.

For TDTR measurements with laser beams that have 1/e2 radii less than 5 μm, in situ measurements of the beam intensity profiles on the sample were necessary to prevent systematic errors in w0 that can cause result in spot size and frequency-dependent ΛA values19.

When performing FDTR measurements, our experimental setup remains nearly the same as for TDTR measurements; however, the Ti:sapphire oscillator used to generate the train of pump and probe pulses is dropped out of mode lock, thereby replacing the train of pulses with a CW beam.

Si and MgO samples were prepared with different surface treatments and different metal film coatings. The geometry of the samples that were characterized are Al/2 nm SiO2/Si, Al/11 nm SiO2/ Si, Ta/2 nm SiO2/Si, Ta/Si, Al/3 nm SiO2/Si0.99Ge0.01, Ta/MgO and Al/MgO. The Si samples with 2–3 nm of SiO2 were untreated commercial wafers with a native oxide. Thicker layers of thermal oxide were grown by heating Si wafers in an oven to 950 °C for 5 min at a ramp rate of 5 °C per min. The thickness of SiO2 was measured using variable angle spectroscopic ellipsometry. The Si substrate for the Ta/Si sample was HF treated to remove the native oxide and then loaded into a high vacuum sputtering chamber. The thin metal films were deposited on the Si, Si:B, Si0.99Ge0.01 and MgO substrates under high vacuum. MgO samples were annealed at ≈800 °C under high vacuum for 1 h before Al and Ta deposition. Si samples that were coated with Al films were heated to ≈600 °C and then allowed to cool to room temperature before deposition to provide cleaner interfaces. The Ta was deposited on the MgO substrate at ≈700 °C to the form the α (bcc) phase34. On Si, the Ta film was deposited slightly below 600 °C to prevent the formation of an extensive Ta-Si silicide layer at the interface. Picosecond acoustics16,35 and Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy confirmed that TaSi2 or Ta2O5 layers of appreciable thickness were not formed. For control experiments, Al and Ta films were also deposited on Si wafers that had 105 nm layers of thermal oxide on the surface, and Al films were deposited on single crystal Al, Cu, and Ni substrates, see Supplementary Fig. 7. The boron doping concentration in the Si:B sample was 1.6 × 1019 cm−3, determined by secondary ion mass spectroscopy. We determined the relative sensitivity factor for boron in our secondary ion mass spectroscopy measurement by measuring a reference sample of Si with a known concentration profile of ion implanted boron.

Control TDTR measurements of Al/Ni and Al/SiO2 samples were performed as a function of w0 and f, see Supplementary Fig. 7. We observed no dependence of ΛA on w0 or f outside of our estimated experimental uncertainty of 8%. A radial thermal conductivity for Ni within 5% of the through-plane value was derived from beam-offset measurements at w0=1.05 μm and f=1.1 and 10 MHz, see Supplementary Fig. 8. We also performed control measurements to confirm the temperature reading of our cryostat for low-temperature experiments, see Supplementary Fig. 9.

In addition to the samples described above, a separate set of Al-coated Si, Si0.99Ge0.01, Si0.2Ge0.8 and Ge samples were prepared specifically for the apparent interface conductance measurements shown in Fig. 5. These samples were first HF treated before being loaded in a high vacuum sputtering chamber to remove as many extrinsic differences between the interfaces as possible, such as different thicknesses of native oxide. In addition to the HF dip, the Si and Si0.99Ge0.01 samples were heated to ≈700 °C and the Si0.2Ge0.8 and Ge samples were heated to ≈450 °C in high vacuum for 30 minutes and then allowed to cool to room temperature before Al deposition.

Ballistic/diffusive model for thermal transport

The thermal response measured in TDTR experiments in heat transfer problems where Fourier theory is invalid can be understood with a ballistic/diffusive model. By ballistic phonons, we mean phonons with MFPs that are comparable to, or larger than, the important length scales of the temperature profile and therefore require a nonlocal expression for the heat current. By diffusive phonons, we mean phonons whose heat current is well described by Fourier theory because their MFPs are shorter than the important length scales of the temperature profile. The new ballistic/diffusive framework we describe here is based on the derivation presented in Aschroft and Mermin for Λ of a Drude metal36, and builds on our prior work in ref. 3. Our ballistic/diffusive model draws on concepts outlined in two-fluid models for phonon transport described by Armstrong37 and more recently by Maznev et al.12

High-wavevector phonons (q>q0), which contain the vast majority of the solid’s heat capacity (Fig. 2b), form a thermal reservoir12,37. In our model, the phonon wavevector that divides the high- and low-wavevector phonons, q0, must meet the requirement that ℓ(q0)≪w0 and ℓ(q0)≪dp so that all high-wavevector phonons are diffusive and the mean occupation of all high-wavevector phonons at all positions is well described with a single temperature profile, T(r, z).

The dominant inelastic scattering mechanism for low-wavevector phonons is three-phonon processes that involve two high-wavevector phonons12,38. Therefore, we follow Maznev et al. and neglect coupling between low-wavevector phonons and assume that low-wavevector phonons are only coupled to high-wavevector phonons. Then, the thermal reservoir transports heat both diffusively and by radiating and absorbing the lower frequency phonons with q<q0 and the total heat current at position ρ due to all phonons is

where j sums over polarizations, Λ0 is the total thermal conductivity due to phonons with q>q0 and JNL(ℓ(q)) is the nonlocal heat current due to phonons with a MFP ℓ being radiated and absorbed from the thermal reservoir. The nonlocal heat current across a plane, q, in a homogenous solid due to a low-wavevector phonon excitation is equal to the product of the difference in the number density of thermally excited phonons travelling in the positive and negative directions, Δn(q)D(q)/2, the excitation’s group velocity, v(q) and the difference in energy between excitations travelling in the positive and negative directions, ℏω(q), that is, JNL=ℏωΔnD(q)v/2, where n is the Bose–Einstein occupation number and D is the volumetric density of states. Here, the difference in thermally occupied states depends on the differences in temperature of the solid where and when the low-wavevector phonons travelling in the positive and negative directions last scattered. Because the most important timescale in our experiment, 1/f, is much longer than phonon lifetimes, we can neglect any temporal lag when relating Δn to T. Then, for a one-dimensional problem3,

Here,  is the average temperature difference between phonons with MFP ℓ(q) travelling in the positive and negative direction.

is the average temperature difference between phonons with MFP ℓ(q) travelling in the positive and negative direction.

A physically intuitive approximation for  ; at position ρ is36

; at position ρ is36

because, on average, phonons have travelled a distance ℓ since last scattering. A more general expression for  that also accounts for the probability of scattering at an interface is derived in Supplementary Methods. When the temperature profile near ρ can be accurately described by a first-order Taylor series36, that is,

that also accounts for the probability of scattering at an interface is derived in Supplementary Methods. When the temperature profile near ρ can be accurately described by a first-order Taylor series36, that is,

the nonlocal expression in equation (6) for the heat current reduces to the local expression known as Fourier’s law. In other words, Fourier’s law will accurately predict the heat current due to phonon with wavevector q provided equation (8) is a reasonable approximation.

When the heat transfer problem in a TDTR or FDTR experiment is purely diffusive, the distance heat can diffuse in one period of oscillation determines the through-plane length scale of the temperature profile and is known as the thermal penetration depth,  . In a ballistic/diffusive transport problem, this length scale of the temperature profile is decreased because ballistic phonons carry less heat than Fourier’s law predicts. Therefore, we can bound the through-plane temperature profile length scale as less than dp but larger than

. In a ballistic/diffusive transport problem, this length scale of the temperature profile is decreased because ballistic phonons carry less heat than Fourier’s law predicts. Therefore, we can bound the through-plane temperature profile length scale as less than dp but larger than  , where Λ0 is the thermal conductivity of high-wavevector phonons.

, where Λ0 is the thermal conductivity of high-wavevector phonons.

When the heat transfer problem is not one-dimensional, we must integrate over all directions and equation (6) becomes

where j labels phonon polarization, θ1, θ2, φ1 and φ2 are determined by direction, i,R is the probability of reflection for a Si phonon impinging on the metal/Si interface and vi,j is the component of the group velocity of a phonon with polarization j in direction i. In the radial direction, θ1=0, θ2=π, φ1=−π/2, φ2=π/2 and vi,j=vj cos φ sin θ. In the through-plane direction, θ1=0, θ2=π/2, φ1=0, φ2=2π and vi,j=vj cos θ.

For the group of phonons that satisfy the limit ℓ≫dp, equation (9) predicts that the heat current in through-plane direction is14

where CL and CT are the collective volumetric heat capacities of longitudinal and transverse phonons that satisfy ℓ≫dp, vL and vT are the average longitudinal and transverse group velocities of ballistic phonons and TM is the temperature of the metal transducer. In the r direction, the heat carried by phonons with ℓ≫w0 is zero.

Ballistic and diffusive phonons in our model are affected by the presence of a boundary in different ways. For the diffusive channel, we assume the boundary condition Jz(z=0)=G0ΔTz=0, is an adequate description of the effect of the interface on diffusive thermal transport. Here, G0 is the diffusive thermal conductance. For the ballistic channel, the heat current across the interface is given by equation (9) with the exclusion of phonons travelling toward the metal surface, and can be viewed in terms of a ballistic conductance,  , where GB=(1−R)C(q<q0)v/4 is the conductance of ballistic phonons. In addition, the presence of a boundary alters the heat carried by long MFP phonons in the substrate within a distance ℓ of the interface, because the reflection and transmission of phonons alters

, where GB=(1−R)C(q<q0)v/4 is the conductance of ballistic phonons. In addition, the presence of a boundary alters the heat carried by long MFP phonons in the substrate within a distance ℓ of the interface, because the reflection and transmission of phonons alters  (Fig. 8). In the main text, we labelled this latter effect an interfacial nonequilibrium thermal resistance because the interface is preventing thermal equilibrium between phonons near z=0.

(Fig. 8). In the main text, we labelled this latter effect an interfacial nonequilibrium thermal resistance because the interface is preventing thermal equilibrium between phonons near z=0.

The expression for JNL(ℓ(q)) in equation (9) converges to the Fourier theory prediction for the heat current when ℓ(q) is much smaller than the length scales of the temperature profile. Therefore, the total heat current predicted by equation (5) will not be sensitive to the value of q0 chosen as long as equation (8) is satisfied for ℓ(q>q0).

Self-consistent criteria for choosing the value of q0 for a given material can now be outlined. The requirement that equation (8) is valid for ℓ(q0) provides a restriction on how small q0 can be. A restriction on how large q0 can be is provided by our two assumptions that low-wavevector phonons have a negligible collective heat capacity in comparison with high-wavevector phonons, C(q<q0)≪C(q>q0), and that the dominant scattering mechanism for low-wavevector phonons is absorption/emission from the thermal reservoir. The criterion that C(q<q0)≪C(q>q0) will typically provide a stricter limit on the upper bound of q0 than the absorption/emission criterion because the spectral distribution of the heat capacity only depends on the density of occupied states, while the probability of a low-wavevector phonon scattering with two other phonons depends on both the density of occupied states and the three-phonon matrix element, and the three-phonon matrix element is larger for scattering events that involve high-wavevector phonons12. We set q0 in all materials so that ℓ(q0)=dp (20 MHz)/5 for both longitudinal and transverse phonons, see supplementary Methods. This satisfies the requirement that the total heat current predicted by equation (5) is insensitive to q0. In addition, it leaves more than 90% of the total heat capacity with the high-wavevector phonons in the materials we study here.

To compare with our experimental data, we use our ballistic/diffusive model to calculate effective thermal conductivities, and then use these effective thermal conductivities to generate theoretical values of GA and ΛA as a function of w0 and f (solid lines in Figs 3, 5 and 6). Further details of our calculation are provided in Supplementary Methods. Supplementary Fig. 10 compares the assumptions of specular versus diffuse reflection of phonons from the interface. Supplementary Figs 11–13 illustrate how with properly defined effective in-plane and through-plane thermal-conductivities, Kr(z) and Kz(z), the predictions of Fourier’s law and equation (9) agree.

To summarize how we fixed our model parameters, once q0 is fixed so that all high wave vector phonons are diffusive, and the RTA models are used to fix the MFPs and heat capacities of the short wavevector phonons, the only free parameters in the ballistic/diffusive model are G0 and R. We fixed R=0 for all samples and calculations with the exception of Figs 6 and 8. Figures 6 and 8 include both the adiabatic and radiative limits of our model’s predictions, and is representative of the effect that varying R has on the calculations. We fixed G0 for Si and Si0.99Ge0.01 based on TDTR measurements of Si. We fixed G0 for Ge and Si0.2Ge0.8 based on TDTR measurements of Ge. Therefore, our model predictions for ΛA of Si, Ge, Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si0.2Ge0.8 involve no fitting parameters. Our model predictions for GA of Si and Ge involve one fitting parameter (G0) and our model predictions for GA of Si0.99Ge0.01 and Si0.2Ge0.8 involve no fitting parameters. The ΛA predicted by our ballistic/diffusive model is insensitive to q0 and G0; for example, a 5% change in either results in less than a 0.2% change in ΛA predicted for Si0.99Ge0.01 at 10 MHz. GA predicted by our model is sensitive to G0; for example, a 5% change in the value of G0 results in a 3% change in GA predicted for Si0.99Ge0.01 at 10 MHz.

The accuracy of our ballistic/diffusive model predictions depends on four factors: (1) the accuracy of our RTA model’s predictions for the thermal conductivity spectral distribution λ(q), (2) the accuracy of our assumptions regarding interfacial-phonon scattering, (3) the accuracy of our assumption that only diffusive phonons store a significant amount of heat and (4) the accuracy our nonlocal expression for the heat current equation (9). Therefore, the accuracy of quantitative predictions could be improved in future work with a more sophisticated model. For example, our model’s treatment of interfacial transport assumes, without rigorous justification that low-wavevector phonons impinging on the interface from the nonmetal side have a constant reflection probability (usually zero), and that a radiative boundary condition is a valid description of interfacial transport for high-wavevector phonons. Our model’s requirement that the vast majority of a solid’s heat capacity is due to phonons with MFPs much shorter then temperature profile length scales limits its applicability to problems where the vast majority of thermally excited phonons do not require a nonlocal expression for the heat current, precluding our ballistic/diffusive model from making predictions at low temperatures. Our nonlocal expression for the heat current does not distinguish between elastic and inelastic scattering, which should have different effects on the nonequilibrium length scale11. Finally, another weakness in our model predictions is that to predict the thermal response of our samples at 1/f timescales, we used our ballistic/diffusive model to derive effective thermal properties, Kz(z) and Kr(z), as inputs for the heat diffusion equation. A fully rigorous calculation would be self-contained by directly calculating the thermal response of the solid on 1/f timescales.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wilson, R. B. et al. Anisotropic failure of fourier theory in time-domain thermoreflectance experiments. Nat. Commun. 5:5075 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6075 (2014).

References

Regner, K. T. et al. Broadband phonon mean free path contributions to thermal conductivity measured using frequency domain thermoreflectance. Nat. Commun. 4, 1640 (2013).

Yang, F. & Dames, C. Mean free path spectra as a tool to understand thermal conductivity in bulk and nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 87, 035437 (2013).

Wilson, R. B., Feser, J. P., Hohensee, G. T. & Cahill, D. G. Two-channel model for nonequilibrium thermal transport in pump-probe experiments. Phys. Rev. B 88, 144305 (2013).

Minnich, A. J. et al. Thermal conductivity spectroscopy technique to measure phonon mean free paths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 095901 (2011).

Highland, M. et al. Ballistic-phonon heat conduction at the nanoscale as revealed by time-resolved x-ray diffraction and time-domain thermoreflectance. Phys. Rev. B 76, 075337 (2007).

Koh, Y. K. & Cahill, D. G. Frequency dependence of the thermal conductivity of semiconductor alloys. Phys. Rev. B 76, 075207 (2007).

Siemens, M. E. et al. Quasi-ballistic thermal transport from nanoscale interfaces observed using ultrafast coherent soft X-ray beams. Nat. Mater. 9, 26–30 (2010).

Pop, E. Energy dissipation and transport in nanoscale devices. Nano Res. 3, 147–169 (2010).

Kanatzidis, M. G. Nanostructured thermoelectrics: the new paradigm? Chem. Mater. 22, 648–659 (2009).

Johnson, J. A. et al. Direct measurement of room-temperature nondiffusive thermal transport over micron distances in a silicon membrane. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 025901 (2013).

da Cruz, C. A., Li, W., Katcho, N. A. & Mingo, N. Role of phonon anharmonicity in time-domain thermoreflectance measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 083108 (2012).

Maznev, A. A., Johnson, J. A. & Nelson, K. A. Onset of nondiffusive phonon transport in transient thermal grating decay. Phys. Rev. B 84, 195206 (2011).

Minnich, A. J. Determining phonon mean free paths from observations of quasiballistic thermal transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 205901 (2012).

Allen, P. B. Heat conduction by phonons across a film. eprint arXiv:1308.2890, 5 (2013).

Yang, H.-S. et al. Anomalously high thermal conductivity of amorphous Si deposited by hot-wire chemical vapor deposition. Phys. Rev. B 81, 104203 (2010).

Losego, M. D., Grady, M. E., Sottos, N. R., Cahill, D. G. & Braun, P. V. Effects of chemical bonding on heat transport across interfaces. Nat. Mater. 11, 502–506 (2012).

Stoner, R. J. & Maris, H. J. Kapitza conductance and heat flow between solids at temperatures from 50 to 300 K. Phys. Rev. B 48, 16373–16387 (1993).

Cahill, D. G. et al. Nanoscale thermal transport. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 793–818 (2003).

Feser, J. P. & Cahill, D. G. Probing anisotropic heat transport using time-domain thermoreflectance with offset laser spots. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 104901 (2012).

Garg, J., Bonini, N., Kozinsky, B. & Marzari, N. Role of disorder and anharmonicity in the thermal conductivity of silicon-germanium alloys: a first-principles study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 045901 (2011).

Asheghi, M., Kurabayashi, K., Kasnavi, R. & Goodson, K. E. Thermal conduction in doped single-crystal silicon films. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 5079–5088 (2002).

Fulkerson, W., Moore, J. P., Williams, R. K., Graves, R. S. & McElroy, D. L. Thermal conductivity, electrical resistivity, and seebeck coefficient of silicon from 100 to 1300°K. Phys. Rev. 167, 765–782 (1968).

Cahill, D. G. Analysis of heat flow in layered structures for time-domain thermoreflectance. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 5119–5122 (2004).

Freedman, J. P. et al. Universal phonon mean free path spectra in crystalline semiconductors at high temperature. Sci. Rep. 3, 2963 (2013).

Tamura, S. Isotope scattering of dispersive phonons in Ge. Phys. Rev. B 27, 858–866 (1983).

Ward, A. & Broido, D. A. Intrinsic phonon relaxation times from first-principles studies of the thermal conductivities of Si and Ge. Phys. Rev. B 81, 085205 (2010).

Garg, J., Bonini, N. & Marzari, N. inLength-Scale Dependent Phonon Interactions Vol. 128 Topics in Applied Physics eds Shindé Subhash L., Srivastava Gyaneshwar P. Chapter 4, 115–136Springer (2014).

Li, W. et al. Thermal conductivity of diamond nanowires from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195436 (2012).

Riley, K. F., Hobson, M. P. & Bence, S. J. Mathematical methods for physics and engineering Cambridge University Press (2006).

Young, D. A. & Maris, H. J. Lattice-dynamical calculation of the Kapitza resistance between fcc lattices. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3685–3693 (1989).

Kremer, R. K. et al. Thermal conductivity of isotopically enriched 28Si: revisited. Solid State Commun. 131, 499–503 (2004).

Ding, D., Chen, X. & Minnich, A. J. Radial quasiballistic transport in time-domain thermoreflectance studied using Monte Carlo simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 143104 (2014).

Wilson, R. B., Apgar, B. A., Martin, L. W. & Cahill, D. G. Thermoreflectance of metal transducers for optical pump-probe studies of thermal properties. Opt. Express 20, 28829–28838 (2012).

Sato, S. Nucleation properties of magnetron-sputtered tantalum. Thin Solid Films 94, 321–329 (1982).

Hohensee, G. T., Hsieh, W.-P., Losego, M. D. & Cahill, D. G. Interpreting picosecond acoustics in the case of low interface stiffness. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 114902 (2012).

Ashcroft, N. W. & Mermin, N. D. Solid State Physics Thomson Learning (1976).

Armstrong, B. H. Two-fluid theory of thermal conductivity of dielectric crystals. Phys. Rev. B 23, 883–899 (1981).

Herring, C. Role of low-energy phonons in thermal conduction. Phys. Rev. 95, 954–965 (1954).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by AFOSR contract number AF FA9550-12-1-0073 and was carried out in part in the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory Central Research Facilities, University of Illinois. R.B.W. thanks the Department of Defense for the NDSEG fellowship that supported him during this work, Joseph P. Feser for sharing his preliminary data for MgO and his assistance with beam-offset measurements and Dongyao Li for helpful discussions regarding heater/thermometer symmetry in heat transfer problems.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B.W. designed and carried out the experiments, conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript with the assistance and supervision of D.G.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-13, Supplementary Notes 1-4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 861 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, R., Cahill, D. Anisotropic failure of Fourier theory in time-domain thermoreflectance experiments. Nat Commun 5, 5075 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6075

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6075

This article is cited by

-

Observation of phonon Poiseuille flow in isotopically purified graphite ribbons

Nature Communications (2023)

-

High thermal conductivity in wafer-scale cubic silicon carbide crystals

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Inelastic phonon transport across atomically sharp metal/semiconductor interfaces

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Non-Fourier phonon heat conduction at the microscale and nanoscale

Nature Reviews Physics (2021)

-

Geometrical quasi-ballistic effects on thermal transport in nanostructured devices

Nano Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.