Abstract

Ubiquitination governs oscillation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity through a periodic degradation of cyclins for orderly cell cycle progression; however, the mechanism that maintains the constant CDK protein levels throughout the cell cycle remains unclear. Here we show that CDK6 is modified by small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO1) in glioblastoma, and that CDK6 SUMOylation stabilizes the protein and drives the cell cycle for the cancer development and progression. CDK6 is also a substrate of ubiquitin; however, CDK6 SUMOylation at Lys 216 blocks its ubiquitination at Lys 147 and inhibits the ubiquitin-mediated CDK6 degradation. Throughout the cell cycle, CDK1 phosphorylates the SUMO-specific enzyme, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme9 (UBC9) that in turn mediates CDK6 SUMOylation during mitosis; CDK6 remains SUMOylated in G1 phase and drives the cell cycle through G1/S transition. Thus, SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation constitutes a mechanism of cell cycle control and inhibition of this SUMOylation pathway may provide a strategy for treatment of glioblastoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SUMO is a conserved member of the ubiquitin-related protein family1,2. Human genome encodes four SUMO isoforms: small ubiquitin-like modifier 1–4 (SUMO1–4); however, it is unclear whether SUMO4 can be conjugated and SUMO2 and SUMO3 are commonly referred to as SUMO2/3 because they share 97% amino-acid sequence and cannot be distinguished by any antibodies3. In contrast, SUMO1 is distinct from SUMO2/3 because it shares only 50% amino acids homology. SUMO conjugation, that is, SUMOylation is now established as a key posttranslational modification pathway distinct from ubiquitination. Ubiquitin is covalently attached to a lysine residue of substrates through catalytic reactions by ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1), conjugating enzyme (E2) and ligase (E3) and the conjugated ubiquitin is removed by deubiquitinating enzymes4. In this ubiquitination process, E3 ligases directly transfer ubiquitin to substrates. In contrast, SUMO E3 ligases may not be required for SUMOylation since UBC9 binds substrates directly5. SUMO modifies a large set of substrates6,7, but its modification pathway is surprisingly simple and composed of an E1 (SUMO-activating enzyme 1/2; SAE1/2), an E2 (UBC9), a handful E3 ligases and less than dozen SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs)8,9. This is in sharp contrast to ubiquitin pathway that consists of tens of E2, hundreds of E3 and more than fifty proteases10. One of the well established functions of ubiquitin is to target proteins to the 26S proteasome for degradation; however, recent studies indicate that SUMO regulates ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis11. Clearly, more SUMO enzymes and regulatory mechanisms are emerging that regulate diverse biological processes12.

Ubiquitination is well known for regulation of cell cycle through degradation of cyclins. The cell cycle is driven mainly by four CDKs: the interphase CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6 and the mitotic CDK113. These kinases are activated by binding to their activating cyclins and forming specific complex in each cell cycle phase: CDK4/6-cyclin D complexes in G1 phase, CDK2–cyclin E complex in S phase and CDK1–cyclin A/B complexes in G2/M phases. This periodicity is governed by oscillation of CDK activity through periodic ubiquitin-mediated degradation of CDK-activating cyclins14. Two ubiquitin E3 ligase complexes control the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of cyclins through the cell cycle: the Skp1-cullin 1-F-box complex destroys cyclins from G1 to M phase and the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome degrades M to G1 phase cyclins. In contrast, the CDK protein levels are constant through the cell cycle, but the mechanisms that maintain CDK proteins are unclear. In human cancers, the elevation of CDK proteins is linked to gene amplification and overexpression15; however, the amplification occurs only in a small set of human cancers according to cancer genomes16,17.

Recent studies indicate the role of SUMOylation in cancer development and progression18. SENP1 removes SUMO from reptin and release its repression of metastasis suppressor gene KAI1 (ref. 19); oncogenic Ras induces carcinogenesis through inhibition of MEK SUMOylation20; and SUMOylation-defective microphthalmia-associated transcription factor predisposes to melanoma and renal cell carcinoma21; SAE2 contributes to Myc-dependent cancer formation22. Here, we investigate how SUMOylation regulates development and progression of glioblastoma, the most common and lethal human brain cancer23. Through biochemical and functional analyses of CDK6 in glioblastoma, we unveil the molecular cascades of SUMOylation, ubiquitination and phosphorylation in regulation of CDK6 protein through the cell cycle using the tumour tissues, cell lines, initiating cells and xenografts24. The results reveal an active SUMO1 conjugation pathway in glioblastoma and show that CDK6 SUMOylation stabilizes the protein and its kinase activity through inhibition of its ubiquitination and the ubiquitin-mediated degradation. CDK1 phosphorylates UBC9 that in turn mediates CDK6 SUMOylation during mitosis and CDK6 SUMOylation remains from M to G1 phase and thus drives the cell cycle through G1–S transition. Selective inhibition of SUMO1 induces G1 arrest and inhibits cell growth and the formation and progression of the tumour-initiating cell-derived glioblastomas. This study unveils the mechanisms by which SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation contributes to the development and progression of glioblastoma and proves the principle that inhibition of this SUMO1 conjugation may provide a therapeutic benefit against this devastating human disease.

Results

SUMO1 conjugation drives the cell cycle through G1/S transition

To investigate the role of SUMO1 in human glioblastoma, we examined the protein levels of SUMO enzymes in patient-derived tumour tissues as compared with normal brain tissues. SUMOylation is reversible due to the presence of SENPs that remove conjugated SUMO from its substrates8,9. To protect the conjugation, tissues were lysed in a sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) denaturing buffer supplemented with the SUMO protease inhibitor N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)7. Western blotting revealed the elevated levels of SEA1, UBC9 and SUMO1-conjugated proteins in the tumours as compared with normal brains (Fig. 1a); thus, SUMO1 conjugation is overactive in glioblastoma. To confirm this at cell levels, we examined glioblastoma-derived cell lines and human brain-derived astrocytes25 and showed the elevation of SUMO1-conjugated proteins in the cell lines as compared with normal human astrocytes (Fig. 1b).

(a) Normal human brain and glioblastoma tissue samples were examined by western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left). β-Actin was used as the protein loading control and the molecular weight were indicated (left). (b) Three human astrocyte samples and two glioblastoma cell lines (top) were tested by western blotting for the expression of SUMO1-conjugated proteins and CDK6. (c) LN229 cells were transduced or not with the empty, scramble control, SUMO1 shRNA as indicated (top) and examined by western blotting using a SUMO1 antibody. (d) Three cell lines transduced with the shRNAs (top) were analysed for cell growth for 4 days (points: means; scale bar, s.e.; n=6 from two independent experiments; ***P<0.001; student’s t-test). (e,f) The transduced cell lines were analysed by flow cytometry for cell cycle (e) and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (f) (points: means; scale bar, s.d.; n=3 from two independent experiments; ***P<0.001; student’s t-test).

To define the role of SUMO1 in the tumour, we transduced two independent SUMO1-specific small hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences into glioblastoma cell lines. The transduction of SUMO1 shRNAs resulted in SUMO1 knockdown (Fig. 1c) and growth inhibition of the cell lines tested (Fig. 1d). To evaluate whether SUMO1 drives the cell cycle for the cell growth, we synchronized cell lines in the prometaphase by nocodazole treatment26. The synchronized cells were collected, grown in nocodazole-free medium and thus allowed to progress through the cell cycle. Flow cytometry detected G1 arrest (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1a) and impaired DNA synthesis in the SUMO1 knockdown cells (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 1b). To confirm this, cell lines were synchronized at the G2/M border by the CDK1 reversible inhibitor RO-3306 (ref. 27) and then allowed to progress through cell cycle. SUMO1 knockdown caused G1 arrest (Supplementary Fig. 2). The data suggest that SUMO1 conjugation is required for G1–S transition. Notably, a recent report indicates that SUMO2/3 modifies cyclin E during S phase in Xenopus28.

SUMO1 stabilizes CDK6 for glioblastoma progression

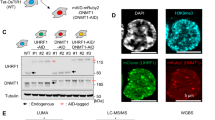

To understand the mechanisms underlying SUMO1 knockdown-induced G1 arrest, we examined cyclins and CDKs and found the decrease of CDK6 and its kinase product, phosphorylated retinoblastoma protein (pRB) in the knockdown cells (Fig. 2a). In contrast, SUMO1 knockdown did not affect the levels of other CDKs (CDK1, CDK2, CDK4), cyclins (cyclin A, cyclin B, cyclin D) and unphosphorylated RB family proteins (RB, RBL1, RBL2) (Supplementary Fig. 3). To test the specificity in SUMO1 regulation of CDK6, we took advantage of the SUMO1 shRNA sequence 613 that targets the 3′-untranslated region and thus allows simultaneous expression of the vector containing the coding region of SUMO1 gene in the shRNA-transduced cells29. The cells were examined by western blotting using His and GFP antibody that also recognizes YFP. The data showed that expression of His- and YFP-tagged SUMO1 led to an increase of SUMO1-conjugated proteins and CDK6 protein as well in the SUMO1 shRNA 613-expressing cells (Fig. 2b), which confirmed that SUMO1 conjugation regulates CDK6 protein. To determine whether CDK6 regulation occurs through gene transcription, total RNA was isolated and real-time PCR analysis revealed the decreased mRNA levels of SUMO1 but not CDK6 in SUMO1 knockdown cells (Fig. 2c); this indicates that SUMO1 conjugation has no effect on CDK6 transcription. Next, we thought to decide if it was the CDK6 decrease that caused G1 arrest. Two independent CDK6-targeting shRNAs were transduced in cell lines; the data showed that CDK6 knockdown reduced pRB levels (Fig. 1c), inhibited cell growth (Fig. 1d), induced G1 arrest (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1a) and blocked DNA synthesis (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 1b), as shown in parallel with SUMO1 knockdown. Taken together, the results suggest that SUMO1 conjugation drives G1–S transition through the posttranslational modification of CDK6 protein.

(a) Three cell lines were transduced or not with the indicated vectors (top) and subjected to western blotting using the antibodies as indicated (left). (b) The SUMO1–613 and control shRNA-expressing LN229 cells were transfected either with YFP-SUMO1 or His-SUMO1 and examined by western blotting using CDK6, His and GFP antibody that also recognized YFP. (c) Total RNA isolated from the cells as described above in (a) was examined by real-time PCR and the mRNA levels of SUMO1 and CDK6 were normalized to the control β-Actin mRNA levels (points: means; scale bar, s.d.; n=6 from two independent experiments; ***P<0.001; **P<0.01; NS: no significance; student’s t-test). (d) Kaplan–Meier curves show the survival of the mice transplanted intracranially with LN229 cells transduced or not with the indicated shRNA vectors (n=10 for each group; ***P<0.001; Log-rank test).

Both CDK4 and CDK6 regulate G1–S transition through the phosphorylation of RB family proteins13 and genomic studies have revealed CDK4 and CDK6 amplification and RB deletion in glioblastoma16. To distinguish the role of CDK4 and CDK6 in the tumours, we analysed a panel of the tumour cell lines known for CDK4 or CDK6 amplification and RB deletion30,31 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). CDK6 was expressed in all cell lines with no correlation to its gene amplification in four of the fourteen cell lines; in contrast, CDK4 was seen in seven of the fourteen lines, two of which had the amplified gene (Supplementary Fig. 4b). This was consistent with the findings that CDK6 was detected in all but CDK4 was seen only in one of the 10 patients’ derived tumours (Fig. 1a). To distinguish CDK4 and CDK6 in cell growth, we transduced two independent CDK4 shRNAs in four CDK4-expressing cell lines in parallel with CDK6 shRNAs. CDK4 knockdown slightly inhibited the growth of two of the four cell lines but still not as effective as CDK6 knockdown even in the lines harbouring CDK4 amplification (Supplementary Fig. 5). The data suggest that CDK6 is the critical G1 phase kinase in glioblastoma.

Next, we thought to examine the role of SUMO1 and CDK6 in parallel in all these cell lines. Knockdown of either SUMO1 or CDK6 inhibited cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 6) and induced G1 arrest in all cell lines except two RB-deleted lines (Supplementary Fig. 7); thus, RB is required for SUMO1/CDK6-driven G1/S transition. To examine this in animal models, we generated intracranial xenografts by injecting LN229 cells in the NOD–SCID mouse brains and showed that either SUMO1 or CDK6 knockdown inhibited the xenograft growth as evident in histological examination (Supplementary Fig. 8a) and prolonged the mouse survival as shown by Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 8b). Clearly, SUMO1 and CDK6 are required for glioblastoma progression.

SUMO1 and CDK6 are required for the tumorigenesis

Because SUMO1 and CDK6 drive glioblastoma xenograft growth, we thought to evaluate whether they are also required for the tumorigenesis. Tumour-initiating cells possess self-renewal and tumorigenic capacity32,33 and neurospheres derived from glioblastomas contain tumour-initiating cells34; thus, we generated neurospheres from patients’ glioblastoma tissues24 and examined the role of SUMO1 and CDK6 in the self-renewal and tumorigenesis of neurospheres. Neurospheres were transduced with either SUMO1 or CDK6 shRNAs; SUMO1 knockdown reduced CDK6 proteins in neurospheres (Fig. 3a); and either SUMO1 or CDK6 knockdown blocked the growth of neurospheres (Fig. 3b). To test the self-renewal, sphere formation assay was carried out and revealed that SUMO1 or CDK6 knockdown inhibited the formation of neurospheres (Fig. 3c). To examine the tumorigenesis, neurospheres were injected in the NOD–SCID mouse brains and glioblastoma xenografts were observed in the mouse brains (Fig. 3d) with the histological features of glioblastoma (Fig. 3e). In contrast, SUMO1 (Fig. 3f) or CDK6 (Fig. 3g) knockdown abolished the initiation of xenografts and prolonged the survival of mice (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Table 1). These data suggest that both SUMO1 and CDK6 are required for the tumorigenesis of glioblastoma.

(a) Three neurospheres were transduced or not with the SUMO1 and CDK6 shRNAs as indicated (top) and tested by western blotting using SUMO1 and CDK6 antibodies. (b) The transduced neurospheres were examined by cell growth for 9 days (points: means; scale bar, s.d.; n=6 from two independent experiments; ***P<0.001; student’s t-test). (c) The transduced neurospheres were also examined by sphere formation assay with the numbers of neurospheres as indicated (left) (points: means; scale bar, s.d.; n=6 from three independent experiments; ***P<0.001; student’s t-test). (d,e) Coronal cerebral section (d) and microscopic section of hematoxylin and eosin (e) reveals the infiltrating glioblastoma on the right side of a mouse brain injected with the neurospheres expressing the control scrambled shRNA. (f,g) The glioblastoma xenograft was not observed in the mouse brain injected with the neurospheres-expressing shRNA targeting SUMO1 (f) or CDK6 shRNA (g). (h) Kaplan–Meier curves show the survival of the mice intracranially injected with the neurospheres transduced with the indicated shRNA vectors (n=6 for each group; ***P<0.001; Log-rank test).

CDK6 protein is modified by SUMO1 but not SUMO2/3

To evaluate whether SUMO1 stabilizes CDK6 through its conjugation, we carried out an in vitro SUMOylation assay in a biochemical reaction consisting of ATP, SAE1/2, UBC9 and CDK6 according to the protocol35. The assay revealed a higher molecular weight form of CDK6, compatible with the conjugation of SUMO1 to CDK6 only in the presence of ATP, SAE1/SAE2 and UBC9 (Fig. 4a). To evaluate this in cells, we carried out an in vivo SUMOylation assay of endogenous CDK6 protein in the following three-steps: (i) to protect the conjugation, cells were lysed in a denaturing buffer supplemented with NEM; (ii) lysates were diluted in a non-denaturing buffer suitable for immunoprecipitation with a CDK6 antibody; and (iii) western blotting using SUMO1 and another CDK6 antibody revealed that CDK6 was conjugated by SUMO1 in all the cell lines tested (Fig. 4b). The failure to detect the SUMO1–CDK6 conjugates in the absence of the SUMO proteases inhibitor NEM further confirmed the specificity of CDK6 SUMOylation (Fig. 4c). Both in vitro and in vivo assays detected a small fraction of the conjugated protein, keeping in line with other studies7; thus, gene transfection was used to investigate the mechanism of CDK6 SUMOylation.

(a) In vitro SUMOylation assay was performed in a reaction with the elements as indicated (top) and examined by western blotting using a CDK6 antibody with the free and conjugated forms of CDK6 indicated (right). (b) Three cell lines were lysed in a denaturing buffer, IPed with a CDK6 antibody with IgG used as a negative IP control and examined by western blotting using SUMO1 and CDK6 antibody. (c) LN229 cells were lysed in a denaturing buffer supplemented with or without NEM and the endogenous CDK6 protein was immunoprecipitated using a CDK6 antibody with IgG as control and tested examined by western blotting using SUMO1 and another CDK6 antibody. (d) LN229 cells transduced or not with SUMO1 and control shRNA (top) were transfected with Flag-CDK6 and myc-UBC9 (left top). Flag IP and whole-cell lysate (WCL) were tested by western blotting for the interaction of Ubc9 and CDK6. (e) LN229 cells were co-transfected with the indicated vectors (top), immunoprecipitated with a CDK6 antibody and examined by western blotting for the presence of Flag-CDK6-His-SUMO1 conjugates (right). (f) LN229 cells were co-transfected with YFP-SUMO3, YFP-SUMO1 and/or Flag-CDK6 and then immunoprecipitated with a Flag antibody. Western blotting using CDK6 and GFP antibody that recognizes YFP detected SUMO1–CDK6 conjugates as indicated (right). (g) Flag immunoprecipitate from YFP-SUMO1, Flag-CDK4 and Flag-CDK6 transfected LN229 cells were examined by western blotting for the presence of Flag-CDK6-YFP-SUMO1 conjugates.

In SUMO1 conjugation, UBC9 binds the substrate RanGap15 and SUMO1 contributes to the interaction of UBC9 and the substrate36. To examine these in SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation, Flag-CDK6 and myc-UBC9 were transfected in SUMO1 or control shRNA-expressing LN229 cells. Transfected cells were lysed in a non-denaturing buffer supplemented with NEM and then immunoprecipitated with Flag antibodies. Western blotting using UBC9 and CDK6 antibodies detected the interaction of UBC9 and CDK6 in control but not SUMO1 shRNA-expressing cells (Fig. 4d); thus, SUMO1 is required for UBC9–CDK6 interaction and CDK6 SUMOylation. Next, Flag-CDK6, Flag-UBC9 and His-SUMO1 were transfected. Flag immunoprecipitation, followed by western blotting using SUMO1 antibodies, revealed that transfection of Flag-UBC9 enhanced SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation (Fig. 4e). To determine whether CDK6 is also the substrate of SUMO2/3, Flag-CDK6 was transfected either with YFP-SUMO1 or YFP-SUMO3; western blotting using CDK6 and GFP antibody that also recognizes YFP identified CDK6 conjugation by SUMO1, but not SUMO3 (Fig. 4f). To confirm this, we transduced two independent SUMO2/3 shRNAs in LN229 cells and shown that CDK6 protein were unchanged in SUMO2/3 knockdown cells by western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 9). To determine whether CDK4 is SUMOylated like CDK6, either Flag-CDK4 or Flag-CDK6 was transfected with YFP-SUMO1; western blotting of Flag immunoprecipitates revealed the conjugation of SUMO1 to CDK6 but not CDK4 (Fig. 4g). Clearly, UBC9 mediates SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation in glioblastoma cells.

CDK6 SUMOylation is not required for its kinase activity

SUMOylation commonly targets the lysine residue within the consensus motif ΨKxE/D (Ψ is a large hydrophobic amino acid)37 or inverted consensus motif38. Both the motifs, however, were not seen in a survey of the CDK6 amino-acid sequence (Fig. 5a). On the other hand, SUMOylation of non-consensus lysine residues were reported35,39. To identify non-consensus lysine residues of the SUMOylation, we replaced each of the eighteen lysine (K) residues of CDK6 by an arginine (R) through point mutagenesis and inserted CDK6 K–R mts in Flag-tagged vectors. Flag-CDK6 wild type (wt) and mutant (mt) were transfected with YFP-SUMO1 in LN229 cells. Western blotting of Flag immunoprecipitates using YFP antibodies identified Lys 216 as the SUMO1 conjugation site (Fig. 5b). To test this in vitro biochemically, we generated Flag-CDK6 K–R mt proteins through an in vitro transcription/translation and confirmed the Lys 216 as the SUMOylation site on CDK6 in an in vitro SUMOylation assay (Fig. 5c).

(a) The amino-acid sequence of CDK6 reveals 18 lysine residues as indicated (red). (b) Each of the 18 Lys (K) residues was replaced with an arginine (R) through point mutagenesis. Flag-tagged CDK6 wt and K–R mt were transfected with YFP-SUMO1 in LN229 cells. The transfected cells were lysed in a denaturing and diluted in a non-denaturing buffer. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a Flag antibody and examined by western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left), revealing YFP-SUMO1-Flag-CDK6 conjugates in the cells transfected with all except K216R (arrow). (c) In vitro SUMOylation assay was carried out in the reaction with the indicated elements (top) and the reaction was analysed by western blotting using a CDK6 antibody. (d) SUMO1 and control shRNA-expressing LN229 cells were transfected with Flag-CDK6 wt and K–R mt. Flag IPs were subjected to kinase assay (top panel) and, together with whole-cell lysate (WCL), examined by western blotting (bottom panel).

To assess the impact of CDK6 SUMOylation on its kinase activity, we first evaluated whether the K216R SUMOylation mt might interact with cyclin D. Flag-CDK6 wt and K216R mt were transfected in LN229 cells. The cells were lysed in a NEM containing non-denaturing buffer, to protect the conjugation and interaction of these proteins. Flag immunoprecipitation, followed by western blotting using cyclin D1 and pRB antibodies, revealed the interaction of cyclin D1 and pRB with Flag-CDK6 wt and K216R mt (Supplementary Fig. 10a). To test CDK6 activity, we carried out a kinase activity assay in which truncated RB was used as a substrate. Flag-CDK6 wt and K216R mt were immunoprecipitated from transfected cells with a Flag antibody and found to interact with cyclin D1 and have CDK6 kinase activity (Fig. 5d). Flag-CDK6 wt was then transfected in SUMO1 and control shRNA-expressing cells and immunoprecipitated with a Flag antibody; kinase assay confirmed its kinase activity in SUMO1 knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Collectively, CDK6 SUMOylation at Lys 216 is not required for its interaction with cyclin D1 and kinase activity.

CDK6 SUMOylation inhibits its ubiquitination and degradation

SUMO1 knockdown reduced CDK6 protein (Fig. 2a); thus, we asked if CDK6 might degrade through ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. SUMO1 and control shRNA-expressing cells were treated with the 26S proteasome inhibitor MG132. While CDK6 protein was reduced in SUMO1 knockdown cells, the inhibition of proteasome caused its dramatic accumulation in a timely fashion (Fig. 6a). In contrast, the CDK2 and CDK4 remained unchanged in these cells. Endogenous CDK6 protein was isolated through immunoprecipitation with a CDK6 antibody. Western blotting using ubiquitin antibodies showed that CDK6 protein was polyubiquitinated in SUMO1 knockdown cells and the treatment of MG132 increased the polyubiquitinated CDK6 proteins (Fig. 6b). To examine CDK6 stability, we measured the half-life of the protein in LN229 cells co-transfected with SUMO1 shRNA and Flag-CDK6. The cells were treated with cycloheximide and Flag-CDK6 levels were determined by western blotting using a Flag antibody and normalizing with control β-actin. The half-life of Flag-CDK6 protein was dramatically reduced from more than 24 h in control to less than 8 h in SUMO1 knockdown cells (Fig. 6c). The data support the notion that, in the absence of SUMO1, CDK6 is ubiquitinated and degrades through the 26S proteasome.

(a) LN229 cells, transduced or not with the indicated shRNAs, were treated with MG132 for the indicated hours (top) and examined by western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left). (b) The transduced cells were IPed by a CDK6 antibody. The IP and whole-cell lysate (WCL) were examined by western blotting using UB and another CDK6 antibody. (c) The half-life of Flag-CDK6 protein was evaluated by western blotting (top) and quantified against the control β-actin protein in SUMO1 and control shRNA-expressing cells (bottom). (d) SUMO1 shRNA-expressing LN229 cells were transfected with Flag-CDK6 wt and K–R mt with HA-K48-polyubiquitin (HA-K48-UB). Flag immunoprecipitates were examined by western blotting using HA and CDK6 antibodies. (e) The SUMO1–613 shRNA-expressing LN229 cells were transfected with Flag-CDK6 wt, K147R and empty vector and analysed by western blotting (top) and cell growth assay (bottom) (points: means; scale bar, s.d.; n=6 from two independent experiments; ***P<0.001; student’s t-test).

There is no consensus motif in ubiquitination; thus, to identify the ubiquitination lysine, we took advantage of Flag-CDK6 K–R mts that were generated for SUMOylation assays (Fig. 5a). Given that K48-linked polyubiquitination mediates protein degradation, Flag-CDK6 wt and K–R mts were expressed in LN229 cells with HA-K48-linked polyubiquitin chain, in which all lysines except K48 were replaced with arginines24. Flag immunoprecipitates were examined by western blotting using a HA antibody, revealing the polyubiquitination of CDK6 wt and all K–R mts except the K147R (Fig. 6d). The data identify Lys 147 as the polyubiquitination site of CDK6.

Next, we evaluated the K147R mt for its kinase activity. Flag-CDK6 wt, K147R and K216R mt were immunoprecipitated from transfected cells; western blotting revealed the interaction of the wt, K147R and K216R mt with cyclin D1; however, the kinase activity was not detected in K147 mt (Supplementary Fig. 11). It seems that Lys 147 is required for CDK6 kinase activity through unknown mechanism. Because the lack of kinase activity even in the complex with cyclin D1, K147R mt was used as a negative control in a rescue experiment to evaluate the kinase activity of non-SUMOylated CDK6 protein. Flag-CDK6 wt and K147R mt were expressed in SUMO1 knockdown cells and expression of K147R mt was higher than wt due to degradation of the wt protein in the absence of SUMO1 (Fig. 2a). However, expression of CDK6 wt but not K147R mt rescued the cells from the SUMO1 knockdown-induced growth inhibition (Fig. 6e); the data further confirm that SUMO1 drives cell growth through stabilizing CDK6 protein.

K216 SUMOylation blocks K147 ubiquitination and degradation

To analyse how SUMOylation regulates CDK6 ubiquitination and degradation, we first confirmed Lys 147 as the ubiquitination site (Supplementary Fig. 12a) and Lys 216 as the SUMOylation site of CDK6 protein in transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Next, we determined whether ubiquitin-negative dominants inhibit CDK6 degradation. Two ubiquitin mts were used as negative dominants: HA-K0 non-conjugated in which all lysine residues were replaced with arginines and HA-K48R mt where Lys 48 was replaced by arginine. While transfection of HA-ubiquitin reduced the levels of K216R SUMOylation mt in a dose-dependent manner, transfection of HA-ubiquitin-negative dominant mts increased the SUMOylation mt (Fig. 7a). In contrast, the levels of K147R ubiquitination mt remained unchanged in the cells; thus, the K216R SUMOylation mutation enhances where the K147R ubiquitination mutation blocks the degradation of CDK6 protein. To confirm this, we examined the half-life of these mts and showed that the protein levels of K216R but not K147R started dropping in transfected cells after 8 h of cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 7b), consistent with the half-life of CDK6 wt in SUMO1 knockdown cells (Fig. 6c).

(a) Flag-CDK6 wt, K216R and K147R mt were transfected in LN229 cells with HA-K48R polyubiquitin (HA-48-UB), HA-ubiquitin (HA-UB) and/or non-conjugated ubiquitin mt (K0-UB) in the concentrations as indicated (top). Flag-CDK6 and HA-ubiquitin were detected by western blotting using Flag and HA antibodies. (b) The half-life of Flag-CDK6 K216R and K147R mt were evaluated by western blotting (top) and quantified against the control β-actin in SUMO1 and control shRNA-expressing cells (bottom) (points: means; scale bar, s.d.; n=6 from two independent experiments). (c) The CDK6 protein structure, generated at http://www.rcsb.org (PDB 2EUF), shows the kinase active site with the ATP binding side chains in the deep cleft between N-terminal and C-terminal lobe from which T-loop arises. K216 of the C-terminal is close to K147 near the kinase active site. (d) LN229 cells were transfected with Flag-CDK6, HA-K48-UB, HA-UB and YFP-SUMO1. Flag IPes and whole-cell lysates (WCL) were tested by western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left).

SUMOylation can inhibit ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation by competition for the same lysine residues39,40; however, it is unknown how SUMOylation regulates ubiquitination through targeting different lysine residues. To address this, we first surveyed the CDK6 structure in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank ( www.rcsb.org; PDB 2EUF). CDK6 protein comprises an amino-terminal lobe and a carboxy-terminal lobe with the kinase active site in the cleft41,42,43. The binding of cyclin D to the α1 helix of the N-terminal lobe causes the shift of the T-loop of the C-terminal out the active site of the cyclin D-CDK6 complex for the kinase activation43. In this structure, Lys 216 is exposed at the surface of the C-terminal lobe and separated from Lys 147 by 12.5 Å at the α-carbon coordinates (Fig. 7c), which predicts that the conjugation of CDK6 at Lys 216 by the globular structure of SUMO1 (ref. 44) may block the access of ubiquitination molecules to the Lys 147 ubiquitination site. To test this notion, we conducted a SUMOylation and ubiquitination competitive assay. Flag-CDK6 was co-transfected with HA-ubiquitin/K48 polyubiquitin chain and/or YFP-SUMO1 in LN229 cells. Western blotting of Flag immunoprecipitates using HA and GFP antibodies revealed that transfection of ubiquitin resulted in shift of CDK6 SUMOylation to polyubiquitination; in contrast, transfection of YFP-SUMO1 inhibited CDK6 polyubiquitination and resumed its SUMOylation in the cells (Fig. 7d). These findings suggest that K216 SUMOylation inhibits K147 ubiquitination and the ubiquitin-mediated degradation.

CDK1 phosphorylates UBC9 for CDK6 SUMOylation in M phase

CDK6 is a G1 kinase; thus, we synchronized LN229 cells in G1 phase and revealed the SUMO1 conjugation of endogenous CDK6 protein in G1 synchronized cells (Supplementary Fig 13a). To further investigate CDK6 SUMOylation through the cell cycle, Flag-CDK6 and YFP-SUMO1 transfected LN229 cells were synchronized by nocodazole treatment and allowed to enter the cell cycle as monitored by flow cytometry. Flag immunoprecipitation revealed the conjugation of SUMO1–CDK6 (Fig. 8a) and the interaction of UBC9–CDK6 in G1, but not S phase cells (Supplementary Fig. 13b). Interestingly enough, the conjugation and interaction levels were higher in the synchronized M phase than G1 phase cells. Because CDK1 activity drives M phase, we evaluated whether CDK1 activity might resume CDK6 SUMOylation when cells passed S phase and entered M phase. Flag-CDK6 and YFP-SUMO1-expressing cells were treated with the CDK1 reversible inhibitor RO-3306. SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation was inhibited by RO-3306 but resumed once RO-3306 was removed and cells entered M phase as evident by the presence of pH3 (Supplementary Fig. 14a) and morphologic observation of nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 14b). The transfected cells were then synchronized by nocodazole and allowed to progress to M phase as evident by the presence of cyclin B1 on western blot. SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation was observed in the cells at M phase, but inhibited by RO-3306 treatment (Fig. 8b). To examine the direct impact of CDK1 activity on CDK6 SUMOylation, we repeated in vitro SUMOylation assay in the presence of cyclin B1–CDK1 complex and showed that the complex enhanced SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation (Fig. 8c). Clearly, CDK1 mediates SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation in M phase.

(a) YFP-SUMO1 and Flag-CDK6-expressing LN229 cells were immunoprecipitated in the hours after release from nocodazole synchronization to the cell cycle as monitored by flow cytometry (low panel). Flag IPes and whole-cell lysate (WCL) were analysed by western blotting with asynchronized cells used as controls (top panel). (b) LN229 cells were co-transfected with YFP-SUMO1 and Flag-CDK6, treated with nocodazole for 20 h and then treated or not with RO-3306 for the indicated hours (top). Flag IP and WCL were analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left). (c) In vitro SUMOylation of CDK6 in the absence and presence of the cyclin B1–CDK1 complex (CDK1/Cycl B1). (d) HEK293 cells were expressed with the tagged proteins, immunoprecipitated and analysed by western blotting (top) and CDK1 kinase assay (bottom). (e) Flag-CDK6 was transfected with Myc-UBC9 wt or S71D mt in LN229 cells, immunoprecipitated using Flag antibodies and tested by western blotting for UBC9–CDK6 interaction. (f) LN229 cells were transfected with Myc-UBC9 WT and S71A mt together with Flag-CDK6 and/or YFP-SUMO1, immunoprecipitated and examined by western blotting. (g) The molecular model shows that CDK1 phosphorylates UBC9 and thus enhances SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation from G2/M to G1 phase, driving the cell cycle through G1/S transition.

CDK1 phosphorylates substrates at the full consensus motif (S/T*-P-x-K/R)45. The presence of a full consensus motif in the UBC9 amino-acid sequence (Supplementary Fig. 15a) suggests that CDK1 activity might contribute to CDK6 SUMOylation through phosphorylation of UBC9 in M phase. Indeed, a recent report showed that CDK1 phosphorylates UBC9 at the consensus Ser 71 (ref. 46). To confirm this, we carried out an in vitro CDK1 kinase assay in a kinase buffer consisting ATP, cyclin B1/CDK1 complex and UBC9 or histone H1 as the CDK1 substrate. A luminescent assay was used to detect the levels of ATP after the reaction. The ATP levels were drastically reduced in the reactions with histone H1 or UBC9 (Supplementary Fig. 15b); the data confirm that UBC9, like histone H1, is the substrate of CDK1. CDK6 was SUMOylated at G1 phase, we thought to evaluate whether the G1 phase CDK4 and CDK6 might phosphorylate UBC9. CDK4 and CDK6 kinase assays consisting of ATP, cyclin D1/CDK4 or CDK6 complex and UBC9 or RB1 as the substrate) failed to reveal UBC9 phosphorylation, which was not detected in CDK2 kinase assay (Supplementary Fig. 15b). Taken together, the data indicate that CDK1 phosphorylates UBC9 in M phase.

Next, we replaced the consensus Ser 71 with Ala (S71A) through point mutagenesis. Myc-UBC9 wt and S71A mt were generated through immunoprecipitation from transfected HEK293 cells and used in the CDK1 kinase assay. The results showed that the S71A mutation abolished the ability of UBC9 to act as a CDK1 substrate (Fig. 8d). To examine the effect of the UBC9 phosphorylation on UBC9–CDK6 interaction, we generated an UBC9 phosphomimic mt through replacing of Ser 71 with Asp (S71D). UBC9 wt or S71D mt was co-transfected with Flag-CDK6 in LN229 cells. Flag-CDK6 was immunoprecipitated and western blotting using UBC9 antibodies revealed that the UBC9 S71D phosphomimic dramatically increased the interaction of UBC9 and CDK6 (Fig. 8e). To further define the role of UBC9 phosphorylation on CDK6 SUMOylation, myc-UBC9 wt and S71A mt were co-transfected with YFP-SUMO1 and/or Flag-CDK6. Flag-CDK6 was immunoprecipitated; western blotting using GFP antibodies showed that the UBC9 wt expression enhanced SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation; in contrast, the UBC9 S71A mt expression ablated SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation (Fig. 8f). Collectively, UBC9 is phosphorylated by CDK1 and mediates SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation during mitosis. SUMO1–CDK6 conjugates remain once cells pass M phase and enter G1 phase and drives the cell cycle through the G1/S transition (Fig. 8g).

Discussion

The current concept in the cell cycle stipulates that constant synthesis without coupled ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis maintains the levels of CDK proteins through the cell cycle14. The elevation of CDK proteins in cancers has been thought due to gene amplifications and overexpression15. Contradictory to these traditional concepts, we identify the G1 phase CDK6 as a substrate of both SUMO1 and ubiquitin and show that CDK6 SUMOylation inhibits its ubiquitination and degradation and stabilizes the protein and kinase activity. CDK6 is SUMOylated through CDK1-mediated phosphorylation of UBC9 in M phase and it remains SUMOylated when cells enter G1 phase. SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation protects CDK6 from ubiquitin-mediated degradation from M to G1 phase and thus drives the cell cycle through G1/S transition in glioblastoma cells.

The results presented here provide a previously unknown mechanism that maintains CDK6 protein through the cell cycle. CDK6 protein is elevated in glioblastoma, which has been linked to its gene amplification; however, the Cancer Genome Atlas project for glioblastoma identified CDK6 gene amplification in only a small set of this cancer16. Here, we show that CDK6 SUMOylation stabilizes its protein and drives the cell cycle through G1/S transition in glioblastoma. CDK6 SUMOylation occurs at G1 but not S phase but resumes when cells pass through S into M phases. In search of the mechanism, we confirm the previous finding that the M phase CDK1 kinase activity phosphorylates UBC9 at the consensus motif Ser 71 (ref. 46) and further show that the Ser71 phosphorylation of UBC9 enhances CDK6 SUMOylation. Of the four kinases CDK1, CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6, only CDK1 kinase phosphorylates UBC9 and the phosphorylated UBC9 mediates CDK6 SUMOylation in M phase. CDK6 remains SUMOylated when cells enter G1 phase and drives the cell cycle through G1–S transition. This notion is in line with the reports that UBC9 is critical for the cell cycle and UBC9 deletion leads to the mitotic catastrophe death of cells22,47.

In analysis of CDK6 SUMOylation and ubiquitination, we unveil a new mechanism by which SUMOylation regulates ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Earlier studies have suggested two distinct models in SUMOylation–ubiquitination cross-talk in regulation of proteolysis: they compete for the same lysine residues and SUMOylation recruits ubiquitin E3 ligases to SUMOylated proteins11. For instance, SUMOylation of IκBα at Lys 21 (ref. 40) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen at Lys 164 (ref. 39) blocks the ubiquitination at the same lysine residue and inhibits the ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. On the other hand, the ubiquitin E3 ligase RING finger protein 4 is recruited to the SUMOylated promyelocytic leukaemia for the protein ubiquitination and degradation48. In this study, we identify Lys 216 as the SUMOylation site and Lys 147 as the ubiquitination site on CDK6 and show that K216 SUMOylation inhibits K147 ubiquitination and the ubiquitin-mediated degradation. In support of this notion, the CDK6 protein structure survey indicates that SUMO1 conjugation to CDK6 at Lys 216 may block the access of molecules to the Lys 147 ubiquitination site for ubiquitination. These findings, therefore, provide a new model for SUMOylation–ubiquitination cross-talk in regulation of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis through targeting different lysine residues.

Recent genetic studies in mice indicates that the interphase CDK4 (ref. 49), CDK2 (ref. 50), cyclin E51, CDK6 (ref. 52) and cyclin D53 are dispensable but the mitotic cyclin A2 (ref. 54) and cyclin B1 (ref. 55) and CDK1 (ref. 56) are critical for normal cells during mouse development. On the other hand, this genetic approach has revealed the essential role in the tumorigenesis of cyclin D1 (ref. 57) and CDK4 (ref. 58) in RAS- and HER2-induced breast carcinoma, CDK4 (ref. 59) in RAS-induced lung carcinoma and cyclin D3 (ref. 60) and CDK6 (ref. 61) in Notch1-induced T-cell leukaemia. Genetic ablation of cyclin D1/D3 and chemical inhibition of CDK4/CDK6 lead to the regression of already formed breast carcinoma and T-cell leukaemia without causing damage to normal cells in adult mice62,63. These studies have proved the principles that interphase CDKs (CDK2, 4, 6) and cyclins (cyclin D, E) act as oncogenes for cancer initiation and maintenance. In addition, the studies have distinguished the role of the G1 phase CDK4 and CDK6 in different cancer types. The data presented here indicate that CDK6, but not CDK4, is the critical G1 kinase in human glioblastoma. CDK6-mediated G1/S transition requires its kinase substrate RB; thus, RB gene status is the primary determinant of the tumour response to the G1 kinase inhibition30,31.

Because CDK4 and CDK6 are dispensable for normal cell cycle, small molecule inhibitors of the kinases have been under development for clinical treatment of human cancers. Unfortunately, the first generation of CDK inhibitors has shown no clinical benefit mainly due to toxicity and lack of specificity15. The new generation of kinase specific inhibitors such as the CDK4/CDK6 dual inhibitor PD033299164 has been generated and entered clinical trials for cancer therapy. The PD0332991 (palbociclib) has recently received the Food agent and Drug Administration breakthrough therapy designation for potential treatment of patients with breast cancer. Our findings that SUMO1–CDK6 conjugation stabilizes CDK6 protein and kinase activity for the development and progression of human glioblastoma highlight the idea that inhibition of SUMO1 conjugation may provide a novel strategy in treatment of glioblastoma. By inducing CDK6 degradation, inhibition of SUMO1 conjugation may enhance the therapeutic efficacy of CDK6 kinase inhibitors such as PD0332991 (palbociclib) in combination treatment of the cancer.

Methods

Human tissues and glioblastoma cell lines

Human glioblastoma tissues and normal human brain tissues from seizure lobectomy were either kindly provided by the London (Ontario) Brain Tumor Tissue Bank (London Health Sciences Center, London, Ontario, Canada) or collected from Emory University in accordance with protocols approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Boards. Human astrocyte cultures were kindly provided by V.W. Yong25. Glioma cell lines LN18, LN71, LN215, LN229, LN235, LN405, LN443, LNZ308 (kindly provided by N. De Tribolet, Lausanne, Switzerland), T98G, U118MG, U138MG, U343MG and U373MG (purchased from the American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dublecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For cell growth assay, cells were grown in 96-well plate for 10 days and quantified using CellTiter 96 AQueous One solution Proliferation Assay (Promega).

Antibodies, plasmids and reagents

The mouse antibodies were used against the human CDK4, CDK6, cyclin D1, cyclin D3, cyclin A, cyclin E2, cyclin B1, p14, p21, RB (Cell Signalling), SUMO1 (Invitrogen), Flag, ubiquitin (Sigma-Aldrich), UBC9, RBL1, RBL2, pRB (S780) (BD Biosciences), HA (Covance), His (Novagen), histone H1, myc and ubiquitin (Santa Cruz). The rabbit antibodies recognized the human CDK2, CDK6 (Santa Cruz), CDK1, cyclin D2, pRB (S780), GFP, p21, p27, GAPDH, phospho(Ser) CDK substrate, phospho-histone H3, UBC9 (Cell Signaling), β-actin (Sigma), UBC9 and SUMO2 (Invitrogen). The working dilutions and catalogue numbers of these antibodies are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

The plasmid pCMV6-Myc-DDK(Flag)-CDK4 and -CDK6 were purchased from Origene and YFP-SUMO1ΔC4 (1–97), YFP-SUMO3ΔC11, pcDNA3 6xHis/SUMO1, pCMV-myc-UBC9, pEF-IRES-P-HA-Ub-K48, pEF-IRES-P-HA-Ub-K0, pEF-IRES-P-HA-Ub-WT and pEF-IRES-P-HA-R48 were kindly provided, respectively, by Frauke Melchior (Max-Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Germany), Ronald T. Hay (University of Dundee, UK), Ying-Yuan Mo (Southern Illinois University, IL) and Zhijian J. Chen (University of Texas Southwestern Medical center, TX). Point K–R mutations of CDK6 and S71A and S71D mutations of UBC9 were generated with Quickchange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) at the Emory Custom Cloning Core Facility.

The reagents used in the study included anti-Flag M2 agarose (Sigma-Aldrich), Flag and myc peptide (Sigma-Aldrich), recombinant CDK6 (Signal Chem), SUMO1, Sea1/Sea2 (Aos1/Uba2, Boston Biochem, Boston), ovalbumin (Sigma), ATP (Boston Biochem), protease inhibitors (Sigma), ubiquitin E1 enzyme, UBC13, UBC5a, ubiquitin, K63 only ubiquitin, K48 only ubiquitin, K0 ubiquitin mt (Boston Biochem), truncated Rb (Signal Chem), kinase buffer (NEB), UBC9 (Boston Biochem), Histone H1 (NEB), CDK1–Cyclin-B1, CDK4–cyclin D1, CDK6–cyclin D1 and CDK2–cyclin E1 complex (Invitrogen), TNT Quick coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega), Kinase-Glo Luminescent Kinase Assay reagent (Promega) and Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes).

shRNA sequences and transduction

The lentiviral shRNA vectors included empty vector (SHC001), scrambled control (SHC002), SUMO1–589 (TRCN0000148589, 5′-CCTTCATATT ACCCTCTCCTT-3′), SUMO1–613 (TRCN0000148613, 5′-CGACCAATGCAAGTGTTCATA-3′), CDK6–747 (TRCN0000039747,5′CGTGGAAGTTCAGATGTTGAT-3′) and CDK6–893 (TRCN0000194893, 5′CATGAGATGTTCCTATCTTAA-3′), CDK4-20 (TRCN0000010520, 5′-ACAGTTCGTGAGGTGGCTTTA-3′), CDK4-64 (TRCN0000018364, 5′-ATGACTGGCC TCGAGATGTAC-3′), SUMO2/3-55 (TRCN0000007655, 5′-GACTGAGAACAATCATAT-3′) and SUMO2/3-56 (TRCN0000007656, 5′-GAGGCAGATCAGATTCCGATT-3′) shRNA vector were from Sigma MISSION shRNA library (Sigma). Each of the lentiviral shRNA vectors were transduced into cells based on the protocol as we reported24. Transduced cells were selected with puromycin.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

In examination of SUMO1-conjugated proteins, tissues and cells were lysed in a denaturing buffer (50 mM Tris–HCL pH 7.4, 5% SDS, 30% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 4 mM sodium tartrate, 1 mM sodium molybdate, 2 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors) supplemented with 20 mM NEM and heated at 90 °C for 10 min. Lysates were subjected to a brief sonication after diluted three times in RIPA buffer. For immunoprecipitation, the lysates were further diluted to 0.1% SDS and immunoprecipitated overnight with anti-CDK6 antibody or anti-Flag M2 agarose. The immunoprecipitates were washed with RIPA buffer and eluted with 2 × Laemmli buffer for endogenous CDK6 or 150 ng μl−1 3 × Flag peptide for Flag-CDK6 and tested by western blotting. Full blots are included in Supplementary Figs 16–21.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg RNA in a reverse transcription reaction (Quantitech Reverse Transcription kit). Quantitative PCR for SUMO1 using Quantitech Primer Assay (QT00014280), CDK6 (QT00019985) or β-actin (QT00095431) as an internal control gene, were performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 FAST real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The expression levels of SUMO1 and CDK6 mRNA were normalized to the β-actin mRNA levels and represented relative to the expression in vector–control cells (means and s.d. from PCR triplicates; the sequences of QT00014280; QT00019985; QT00095431 are available from Qiagen).

In vitro and in vivo SUMOylation

In vitro SUMOylation assay was modified from the reported method35 in 10 μl reaction volume containing 100 ng of CDK6, 1.5 μg of SUMO1, 500 ng of Ubc9, 50 ng of Sea1/Sea2 in a buffer consisting 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, 110 mM KOAc, 2 mM Mg[OAc]2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% Tween-20, 0.2 mg ovalbulmin, 10 mM ATP and protease inhibitors. After 90 min at 30 °C, reactions were stopped by addition of 10 μl 2 × laemmli buffer and analysed by western blotting with CDK6 antibody. Flag-CDK6 proteins were generated using TNT Quick coupled Transcription/Translation system and immunoprecipitated as described above. For in vivo SUMOylation, Flag-tagged vector expressing LN229 cells were immunoprecipitated using a Flag antibody and examined by western blotting.

In vivo ubiquitination

For in vivo ubiquitination, LN229 cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 for the time indicated, lysed in a denaturing buffer as described above and immunoprecipitated overnight with CDK6 antibodies. The cells were co-transfected with HA-K48-Ubiquitin and Flag-CDK6 for 24 h and immunoprecipitated with Flag M2 agarose beads and examined by western blotting using HA and Flag antibodies.

Synchronization and cell cycle analysis

Cells were synchronized in M phase after grown for 20 h in the medium containing 80 ng ml−1 nocodazole that reversibly interferes with microtubule polymerization26. Synchronized cells were collected by shake-off and then grown in nocodazole-free medium. Cells were synchronized in G1 phase after grown for 72 h in serum-free medium. Cells were synchronized at the border of G2/M phases after grown for 24 h in the medium containing 9 μM Ro-3306, a CDK1 reversible inhibitor27. For flow cytometry, cells were fixed and stained with a propidium iodide–RNase solution. For DNA synthesis, cells were incubated for 15 min with 100 μg−1 bromodeoxyuridine and stained with propidium iodide–RNase solution and FITC-conjugated bromodeoxyuridine antibody. Analyses were performed with FACS CantoII (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NY, USA). Flow cytometric data were analysed with FloJo Software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). To observe cells in M phase under fluorescent microscopy, cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33342.

CDK6 and CDK1 kinase assays

CDK6 kinase assay was modified from the reported method65. LN229 cells were lysed with an ice-cold kinase buffer consisting of 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1% Tween-20, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. Lysates were then incubated at 4 °C for 2 h with CDK6 antibody, protein G-agarose or Flag antibody-agarose beads. After washes, CDK6 was immunoprecipitated and incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in 20 μl of reaction buffer (50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) containing 200 ng of truncated Rb and 10 mM ATP. The reaction mixtures were examined by western blotting. The Rb molecules phosphorylated by CDK6 were detected with anti-Ser-780-phosphorylated RB antibody. CDK1 in vitro kinase assay was performed in a 10 μl kinase buffer containing 5 μM ATP, 500 ng UBC9, Histone H1, 100 nM CDK1/Cyclin B1. After 90 min at 30 °C, equal volume of Kinase-Glo Luminescent Kinase Assay reagent was added and luminescence was measured.

CDK6 protein half-life assay

Flag-CDK6 wt was stably expressed in LN229 cells transduced with control and SUMO1–613 shRNA. The transfected cells were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg ml−1) for the indicated times in the Results. Cell extracts from each time points were resolved by SDS–PAGE followed by western blotting using Flag and β-actin antibodies. The β-actin protein levels were used as protein loading control and normalized for the degradation rate of Flag-CDK6 in quantification graph generated by ImageJ software. The β-actin normalized Flag protein levels at 0 h were defined as 100 for each panel control-vector and SUMO1–613.

Neurospheres and mouse intracranial xenografts

For neurosphere formation assay, neurospheres were dissociated from cells and plated at 100 cells per well in 24-well plates and grown in the neurosphere culture conditions as described above for 14 days. The neurospheres formed were counted and presented as the number of neurosphere-forming cells over the total 100 cells plated. The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Emory University. Neurospheres (5 × 104 cells) and LN229 cells (106 cells) were injected in the right striatum of NOD–SCID mice (National Cancer Institute). The mice were followed up and killed until development of the signs (lethargy, ataxia, paralysis or seizure) as defined by the Committee. At necropsy, brains were removed, fixed in 10% neutrally buffered formalin, sliced and embedded in paraffin blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopy examination based on our protocols24.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was carried out using GraphPad PRISM and statistically analysed with Log-rank test. All values are expressed as mean±s.d. Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired Student’s t-test.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Bellail, A. C. et al. SUMO1 modification stabilizes CDK6 protein and drives the cell cycle and glioblastoma progression. Nat. Commun. 5:4234 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5234 (2014).

References

Hay, R. T. SUMO: a history of modification. Mol. Cell 18, 1–12 (2005).

Geiss-Friedlander, R. & Melchior, F. Concepts in SUMOylation: a decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 947–956 (2007).

Gareau, J. R. & Lima, C. D. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 861–871 (2010).

Bhoj, V. G. & Chen, Z. J. Ubiquitylation in innate and adaptive immunity. Nature 458, 430–437 (2009).

Bernier-Villamor, V., Sampson, D. A., Matunis, M. J. & Lima, C. D. Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1. Cell 108, 345–356 (2002).

Golebiowski, F. et al. System-wide changes to SUMO modifications in response to heat shock. Sci. Signal. 2, ra24 (2009).

Becker, J. et al. Detecting endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and tissues. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 525–531 (2013).

Hay, R. T. SUMO-specific proteases: a twist in the tail. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 370–376 (2007).

Mikolajczyk, J. et al. Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO)-specific proteases: profiling the specificities and activities of human SENPs. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26217–26224 (2007).

Bergink, S. & Jentsch, S. Principles of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications in DNA repair. Nature 458, 461–467 (2009).

Creton, S. & Jentsch, S. SnapShot: the SUMO system. Cell 143, 848–848, e841 (2010).

Flotho, A. & Melchior, F. SUMOylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 357–385 (2013).

Malumbres, M. & Barbacid, M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 153–166 (2009).

Nakayama, K. I. & Nakayama, K. Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 369–381 (2006).

Lapenna, S. & Giordano, A. Cell cycle kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 547–566 (2009).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455, 1061–1068 (2008).

Beroukhim, R. et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 463, 899–905 (2010).

Bawa-Khalfe, T. & Yeh, E. T. SUMO losing balance: SUMO proteases disrupt SUMO homeostasis to facilitate cancer development and progression. Genes Cancer 1, 748–752 (2010).

Kim, J. H. et al. Roles of SUMOylation of a reptin chromatin-remodelling complex in cancer metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 631–639 (2006).

Kubota, Y., O’Grady, P., Saito, H. & Takekawa, M. Oncogenic Ras abrogates MEK SUMOylation that suppresses the ERK pathway and cell transformation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 282–291 (2011).

Bertolotto, C. et al. A SUMOylation-defective MITF germline mutation predisposes to melanoma and renal carcinoma. Nature 480, 94–98 (2011).

Kessler, J. D. et al. A SUMOylation-dependent transcriptional subprogram is required for Myc-driven tumorigenesis. Science 335, 348–353 (2012).

Reardon, D. A., Rich, J. N., Friedman, H. S. & Bigner, D. D. Recent advances in the treatment of malignant astrocytoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 1253–1265 (2006).

Bellail, A. C., Olson, J. J., Yang, X., Chen, Z. J. & Hao, C. A20 ubiquitin ligase-mediated polyubiquitination of RIP1 inhibits caspase-8 cleavage and TRAIL-induced apoptosis in glioblastoma. Cancer Discov. 2, 140–155 (2012).

Wang, C. X. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase-5 prevents neuronal apoptosis through ERK-mediated upregulation of Bcl-2. Cell Death Differ. 13, 1203–1212 (2006).

De Brabander, M. J., Van de Veire, R. M., Aerts, F. E., Borgers, M. & Janssen, P. A. The effects of methyl (5-(2-thienylcarbonyl)-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl) carbamate, (R 17934; NSC 238159), a new synthetic antitumoral drug interfering with microtubules, on mammalian cells cultured in vitro. Cancer Res. 36, 905–916 (1976).

Vassilev, L. T. et al. Selective small-molecule inhibitor reveals critical mitotic functions of human CDK1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10660–10665 (2006).

Bonne-Andrea, C. et al. SUMO2/3 modification of cyclin E contributes to the control of replication origin firing. Nat. Commun. 4, 1850 (2013).

Xu, X. M., Yoo, M. H., Carlson, B. A., Gladyshev, V. N. & Hatfield, D. L. Simultaneous knockdown of the expression of two genes using multiple shRNAs and subsequent knock-in of their expression. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1338–1348 (2009).

Wiedemeyer, W. R. et al. Pattern of retinoblastoma pathway inactivation dictates response to CDK4/6 inhibition in GBM. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11501–11506 (2010).

Michaud, K. et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 arrests the growth of glioblastoma multiforme intracranial xenografts. Cancer Res. 70, 3228–3238 (2010).

Singh, S. K. et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 432, 396–401 (2004).

Bao, S. et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 444, 756–760 (2006).

Lee, J. et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell 9, 391–403 (2006).

Castillo-Lluva, S. et al. SUMOylation of the GTPase Rac1 is required for optimal cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1078–1085 (2010).

Sampson, D. A., Wang, M. & Matunis, M. J. The small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) consensus sequence mediates Ubc9 binding and is essential for SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21664–21669 (2001).

Rodriguez, M. S., Dargemont, C. & Hay, R. T. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12654–12659 (2001).

Matic, I. et al. Site-specific identification of SUMO-2 targets in cells reveals an inverted SUMOylation motif and a hydrophobic cluster SUMOylation motif. Mol. Cell 39, 641–652 (2010).

Hoege, C., Pfander, B., Moldovan, G. L., Pyrowolakis, G. & Jentsch, S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419, 135–141 (2002).

Desterro, J. M., Rodriguez, M. S. & Hay, R. T. SUMO-1 modification of IkappaBalpha inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol. Cell 2, 233–239 (1998).

Russo, A. A., Tong, L., Lee, J. O., Jeffrey, P. D. & Pavletich, N. P. Structural basis for inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk6 by the tumour suppressor p16INK4a. Nature 395, 237–243 (1998).

Brotherton, D. H. et al. Crystal structure of the complex of the cyclin D-dependent kinase Cdk6 bound to the cell-cycle inhibitor p19INK4d. Nature 395, 244–250 (1998).

Schulze-Gahmen, U. & Kim, S. H. Structural basis for CDK6 activation by a virus-encoded cyclin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 177–181 (2002).

Reverter, D. & Lima, C. D. A basis for SUMO protease specificity provided by analysis of human Senp2 and a Senp2-SUMO complex. Structure. 12, 1519–1531 (2004).

Holt, L. J. et al. Global analysis of Cdk1 substrate phosphorylation sites provides insights into evolution. Science 325, 1682–1686 (2009).

Su, Y. F., Yang, T., Huang, H., Liu, L. F. & Hwang, J. Phosphorylation of Ubc9 by Cdk1 enhances SUMOylation activity. PLoS ONE 7, e34250 (2012).

Seufert, W., Futcher, B. & Jentsch, S. Role of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme in degradation of S- and M-phase cyclins. Nature 373, 78–81 (1995).

Tatham, M. H. et al. RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 538–546 (2008).

Rane, S. G. et al. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in beta-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat. Genet. 22, 44–52 (1999).

Ortega, S. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat. Genet. 35, 25–31 (2003).

Geng, Y. et al. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell 114, 431–443 (2003).

Malumbres, M. et al. Mammalian cells cycle without the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6. Cell 118, 493–504 (2004).

Kozar, K. et al. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-cyclins. Cell 118, 477–491 (2004).

Murphy, M. et al. Delayed early embryonic lethality following disruption of the murine cyclin A2 gene. Nat. Genet. 15, 83–86 (1997).

Brandeis, M. et al. Cyclin B2-null mice develop normally and are fertile whereas cyclin B1-null mice die in utero. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4344–4349 (1998).

Santamaria, D. et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature 448, 811–815 (2007).

Yu, Q., Geng, Y. & Sicinski, P. Specific protection against breast cancers by cyclin D1 ablation. Nature 411, 1017–1021 (2001).

Yu, Q. et al. Requirement for CDK4 kinase function in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 9, 23–32 (2006).

Puyol, M. et al. A synthetic lethal interaction between K-Ras oncogenes and Cdk4 unveils a therapeutic strategy for non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Cell 18, 63–73 (2010).

Sicinska, E. et al. Requirement for cyclin D3 in lymphocyte development and T cell leukemias. Cancer Cell 4, 451–461 (2003).

Hu, M. G. et al. A requirement for cyclin-dependent kinase 6 in thymocyte development and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 69, 810–818 (2009).

Choi, Y. J. et al. The requirement for cyclin D function in tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell 22, 438–451 (2012).

Sawai, C. M. et al. Therapeutic targeting of the cyclin D3:CDK4/6 complex in T cell leukemia. Cancer Cell 22, 452–465 (2012).

Fry, D. W. et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 1427–1438 (2004).

Phelps, D. E. & Xiong, Y. Assay for activity of mammalian cyclin D-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6. Methods Enzymol. 283, 194–205 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the technical support from Zhaobin Zhang (Neurosurgery, Emory University) and Oskar Laur (Emory Custom Cloning Core Facility). We also thank Ronald T. Hay (University of Dundee, UK), Frauke Melchior (Max-Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Germany), Ying-Yuan Mo (Southern Illinois University, IL) and Zhijian J. Chen (University of Texas Southwestern Medical center, TX) for kindly providing the plasmid YFP-SUMO1ΔC4 (1–97), YFP-SUMO3ΔC11, pcDNA3 6xHis/SUMO1, pCMV-myc-UBC9, pEF-IRES-P-HA-Ub-K48, pEF-IRES-P-HA-Ub-K0, pEF-IRES-P-HA-Ub-WT and pEF-IRES-P-HA-R48. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grant R01-CA129687 (C.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.B. and C.H. designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. A.C.B. performed most of the experiments and J.J.O. carried out the experiments of mouse xenografts and glioblastoma-derived neurospheres. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-21 and Supplementary Tables 1-2 (PDF 3961 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bellail, A., Olson, J. & Hao, C. SUMO1 modification stabilizes CDK6 protein and drives the cell cycle and glioblastoma progression. Nat Commun 5, 4234 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5234

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5234

This article is cited by

-

Stabilization of Pin1 by USP34 promotes Ubc9 isomerization and protein sumoylation in glioma stem cells

Nature Communications (2024)

-

SUMOylation of RALY promotes vasculogenic mimicry in glioma cells via the FOXD1/DKK1 pathway

Cell Biology and Toxicology (2023)

-

The association and clinical relevance of phase-separating protein CAPRIN1 with noncoding RNA

Cell Stress and Chaperones (2023)

-

The SUMOylation and ubiquitination crosstalk in cancer

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases: from biology to tumorigenesis and therapeutic opportunities

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.