Abstract

Any practical realization of entanglement-based quantum communication must be intrinsically secure and able to span long distances avoiding the need of a straight line between the communicating parties. The violation of Bell’s inequality offers a method for the certification of quantum links without knowing the inner workings of the devices. Energy-time entanglement quantum communication satisfies all these requirements. However, currently there is a fundamental obstacle with the standard configuration adopted: an intrinsic geometrical loophole that can be exploited to break the security of the communication, in addition to other loopholes. Here we show the first experimental Bell violation with energy-time entanglement distributed over 1 km of optical fibres that is free of this geometrical loophole. This is achieved by adopting a new experimental design, and by using an actively stabilized fibre-based long interferometer. Our results represent an important step towards long-distance secure quantum communication in optical fibres.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A fundamental application of quantum mechanics is in the development of communication systems with intrinsic unbreakable security1. Although quantum key distribution is theoretically unconditionally secure, it has been experimentally demonstrated that quantum key distribution with realistic devices is prone to hacking2. A definitive solution to these practical attacks depends on the experimental violation of a Bell inequality, allowing communication with security guaranteed by the impossibility of signalling at superluminal speeds3,4,5,6. The security can only be guaranteed if a loophole-free Bell test is performed, a major experimental task that still has not been demonstrated. With single photons, the locality and the detection loopholes have been individually closed in separate experiments7,8,9. Recent experimental demonstrations of Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen steering free of the detection loophole, also constitute an important step towards secure communications10,11,12. Progress has also been made regarding more subtle issues, such as the coincidence-time loophole9,13,14,15.

Secure communication requires distributing quantum entanglement over long distances. The most common method to do it in optical fibres is based on Franson’s configuration16. In the Franson scheme, each of two simultaneously emitted photons is injected into an unbalanced interferometer designed such that the uncertainty in the time of emission makes indistinguishable the two alternative paths each photon can take. Many experiments have been performed using this configuration17,18,19,20,21,22,23, due to energy-time’s innate robustness to decoherence in optical fibres. The problem of this method is that Franson’s configuration has an intrinsic geometrical loophole and, therefore, cannot rule out all possible local explanations for the apparent violation of the Bell Clauser–Horne–Shimony–Holt (CHSH) inequality24,25,26. Current experiments based on Franson’s scheme only rule out local models making additional assumptions27,28,29. On the practical side, this loophole can be exploited by eavesdroppers to break the security of the communication (see, for example, the Trojan horse attack to Franson-based quantum cryptography in ref. 30). Some solutions to this problem have been proposed. One consists of keeping Franson’s configuration but replacing passive by active switchers19. However, this solution has never been implemented in an experiment. Another solution consists of replacing Franson’s interferometers by unbalanced cross-linked interferometers wrapped around the photon-pair source in a ‘hug’ configuration introduced in ref. 25. It has been recently demonstrated in table-top experiments31,32. Going to larger distances was thought to be unfeasible unless costly stabilization systems used for large gravitational wave detectors were applied25.

Here we report the first experimental violation of the Bell CHSH inequality with genuine energy-time entanglement (that is, free of the geometrical loophole) distributed through more than 1 km of optical fibres. The energy-time entangled photon-pair source is placed close to Alice, with one of the photons propagating through a short bulk-optics unbalanced Mach–Zenhder (UMZ) interferometer. The other photon is transmitted through the second UMZ interferometer of the hug configuration, which is composed of 1km long fibre optical arms. We show that a Bell violation can be obtained with a home-made active-phase stabilization system, demonstrating that the hug configuration is indeed practical for long-distance entanglement distribution. The results presented here have major implications for secure quantum communication between parties that are not in the same straight line, opening up a path towards a loophole-free Bell test with energy-time entanglement. We stress that even if the detection and locality loopholes are simultaneously closed in a single experiment, energy-time entanglement will still remain unusable as a resource for device-independent quantum communication if the geometrical loophole is not addressed.

Results

Experimental setup

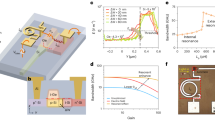

The extensively employed Franson configuration is shown schematically in Fig. 1a. It consists of two UMZ interferometers with the two arms in each one defined as the short (S) and long (L) paths, respectively. In order to avoid single-photon interference, the long–short path difference is made to be much larger than the single-photon coherence length. The issue lies with the fact that the coincident detection events are post-selected for the verification of the Bell violation, and as this post-selection is local, it gives rise to hidden variable models24,25. In the hug configuration, shown in Fig. 1b, the unbalanced interferometers are formed shortly after each output mode of the source using beamsplitters, with the difference that the arms are crossed around the source. This geometrical property assures that the short–long or long–short events can only be routed to either Alice or Bob detectors, effectively removing the need of local post-selections.

(a) Typical fibre-based implementation of Franson’s scheme16,20. (b) Fibre-based version of the hug configuration25. (c) Experimental setup used for implementing the hug configuration with a long fibre-based interferometer. Photon pairs generated in a non-linear crystal are sent through two cross-linked unbalanced Mach–Zehnder interferometers at Alice and Bob’s sites. An optical delay line is used to set the indistinguishability between the short–short and long–long two-photon paths (see the main text for details). The long interferometer comprises a 1-km long telecom single-mode fibre spool in each arm. An extra 40 m of optical fibre is added in the SB arm by the fibre stretcher, which is then balanced by an equal amount of fibre in the other arm. The total arm length in this interferometer is then 1.04 km. The long–short path length difference in both interferometers is 2 m of optical fibres.

The experimental setup used is depicted in Fig. 1c. Degenerate 806 nm photon pairs with orthogonal polarizations are produced from spontaneous parametric downconversion in a bulk non-linear periodically poled potassium titanyl phosphate 20 mm long crystal. The crystal is pumped by a single longitudinal mode continuous wave 403 nm laser with a coherence length greater than 20 m, and with 2.2 mW of optical power. A long-coherence pump laser is necessary to create a fundamental uncertainty in the emission time of the downconverted photons, and thus setup as indistinguishable, the possible paths they can take in both (equally) unbalanced interferometers25. When this condition is satisfied, the Bell state  is generated, where S and L indicate the short and long arms, respectively. The pump laser is weakly focused in the crystal in order to obtain a high collection efficiency in the optical fibres33. The emitted photons are deterministically split by a polarizing beamsplitter, with each output mode sent to a beamsplitter. The two cross-linked interferometers required in the hug configuration are built on these four modes connecting the source to Alice and Bob, Si and Li, with i=A,B. The two modes SA and LA form a short-distance UMZ interferometer. Mode SA is reflected on a piezoelectric mounted mirror responsible for generating the phase shift φa employed by Alice. The final beamsplitter is a single-mode fibre-based component to optimize the overlap of the transverse spatial modes. The long–short path length difference is 2 m. This was chosen such that the time difference is larger than the coincidence temporal window (4 ns). The length of the short arm is approximately 1 m.

is generated, where S and L indicate the short and long arms, respectively. The pump laser is weakly focused in the crystal in order to obtain a high collection efficiency in the optical fibres33. The emitted photons are deterministically split by a polarizing beamsplitter, with each output mode sent to a beamsplitter. The two cross-linked interferometers required in the hug configuration are built on these four modes connecting the source to Alice and Bob, Si and Li, with i=A,B. The two modes SA and LA form a short-distance UMZ interferometer. Mode SA is reflected on a piezoelectric mounted mirror responsible for generating the phase shift φa employed by Alice. The final beamsplitter is a single-mode fibre-based component to optimize the overlap of the transverse spatial modes. The long–short path length difference is 2 m. This was chosen such that the time difference is larger than the coincidence temporal window (4 ns). The length of the short arm is approximately 1 m.

The other two modes, SB and LB connect the source to Bob through a long UMZ fibre-based interferometer. Its arms are built using 1km long telecom spooled single-mode fibres, one spool at each arm. The use of telecom fibres is to demonstrate that the distribution of genuine energy-time entanglement is compatible with the already installed optical-based world-wide network. As multi-mode propagation occurs in the telecom fibres at 806 nm, the arms are connected to a 780 nm single-mode fibre-optical beamsplitter at Bob’s station, performing transverse spatial mode filtering34. This interferometer presents the same 2 m difference between the long and short arms, as in Alice’s case. For the active-phase stabilization a piezoelectric fibre stretcher (FS) with 40 m of wound fibre is used in the SB arm of Bob’s interferometer. Therefore, an equal amount of fibre length must be added to the LB arm for balancing purposes. Thus, the total arm length in this interferometer is 1.04 km. With the exception of the 1 km fibre spools, all other fibre-optic components are single-mode at 780 nm and above. The polarization is adjusted in both arms of the long interferometer with polarization controllers to avoid which-way path information.

Active-phase stabilization

A major experimental challenge in this implementation is the compensation of random-phase fluctuations caused by the environment in long interferometers. This problem is successfully solved here for the first time by adapting to the hug configuration some ideas developed for different purposes35, providing an affordable alternative to the costly stabilization systems suggested in ref. 25. The solution is achieved by injecting a second laser into the system to provide real-time feedback information for the field programmable gate array based control electronics. As mentioned above, a piezoelectric FS composed of 40 m of wound fibre is used for the active-phase stabilization of the long fibre-based interferometer. This device allows for a fibre expansion of up to 5 mm at the maximum driving voltage. This is essential as it allows several wavelengths of phase drift to be compensated in a long interferometer. The FS is driven by the control electronics in response to the environmentally induced phase drifts imposed on the feedback optical signal when propagating in the interferometer. The control system enables phase locking of the interferometer by using a custom designed closed-loop proportional-integral-derivative control algorithm. Additional details are provided in Methods section. A bulk-optics delay line, with a movement range of 150 mm, is used to set LA−SA=LB−SB (see also Methods for additional details). To demonstrate the importance of the active stabilization in the experiment, we show in Fig. 2a the net coincidence counts/s between detectors DA1 and DB1 as a function of the delay line position around the indistinguishability point. The stabilization system was kept active maintaining φb constant while the delay line was moving. In Alice’s side, the piezo-mounted mirror was driven during the measurement with a slowly varying voltage ramp, therefore modulating φa. This is to ensure that two-photon interference fringes are observed in the indistinguishability region. The two-photon interference pattern in Fig. 2a is clearly observed. The crucial point is that two-photon interference cannot be observed without active-phase stabilization due to the rapidly and randomly varying phase drift in a long interferometer. This is shown in Fig. 2b, where the scan in the same delay is performed with the control system turned off and all other settings kept the same as in Fig. 2a.

Long-distance Bell inequality violation

The violation of the Bell CHSH inequality was performed with the delay line set at the center point of the two-photon interference pattern, the active-phase control is kept active and the piezo-mounted mirror once again slowly modulated (this time with an ~30 s period). The Bell CHSH inequality is defined through the expression S=E(φa, φb)+E , where E(φa, φb)=P11(φa, φb)+P22(φa, φb)−P12(φa, φb)−P21(φa, φb), with Pij(φa, φb) corresponding to the probability of a coincident detection at Alice and Bob’s detectors i and j, respectively, while the relative phases φa and φb are applied to Alice and Bob’s interferometers. For the maximum violation of the Bell CHSH inequality, the phase settings are φa=π/4, φb=0,

, where E(φa, φb)=P11(φa, φb)+P22(φa, φb)−P12(φa, φb)−P21(φa, φb), with Pij(φa, φb) corresponding to the probability of a coincident detection at Alice and Bob’s detectors i and j, respectively, while the relative phases φa and φb are applied to Alice and Bob’s interferometers. For the maximum violation of the Bell CHSH inequality, the phase settings are φa=π/4, φb=0,  =−π/4 and

=−π/4 and  =π/2 (refs 26, 31). The phase control system is used to switch between Bob’s two phase settings, 0 and π/2. The eight measured curves across all output combinations are displayed in Fig. 3a–d. The measured average raw visibilitiy is (84.36±0.47)%. When the accidental coincidences are subtracted, the net visibility rises to (95.12±0.20)%. The recorded values of the probability correlation functions (E) for the case with no accidental subtraction are shown in Fig. 3e. The corresponding violation of the Bell CHSH inequality in this case yields S=2.39±0.12, surpassing the classical limit by 3.25 standard deviations. Our experimental results are comparable with previous long-distance Bell experiments using energy-time entanglement based on the Franson configuration18.

=π/2 (refs 26, 31). The phase control system is used to switch between Bob’s two phase settings, 0 and π/2. The eight measured curves across all output combinations are displayed in Fig. 3a–d. The measured average raw visibilitiy is (84.36±0.47)%. When the accidental coincidences are subtracted, the net visibility rises to (95.12±0.20)%. The recorded values of the probability correlation functions (E) for the case with no accidental subtraction are shown in Fig. 3e. The corresponding violation of the Bell CHSH inequality in this case yields S=2.39±0.12, surpassing the classical limit by 3.25 standard deviations. Our experimental results are comparable with previous long-distance Bell experiments using energy-time entanglement based on the Franson configuration18.

Graphs (a–d) show the normalized coincidence detections across Alice and Bob’s detectors without accidental subtraction. (a) and (b) correspond to the cases where φb=0 and (c) and (d) to the cases where φb=π/2. Integration time for each data point is 1 s with an average rate of ≈100 coincidences counts. The rate of single counts is ≈74,000 and 54,000 detections per second for each detector of Alice and Bob, respectively. The curves are obtained varying the phase difference φa in Alice’s interferometer with the moving mirror, while actively keeping fixed the relative phase φb. (e) Shows the measured value for each probability correlation function (E) appearing in the Bell CHSH inequality. Solid black lines show the maximum possible value for each function E. The corresponding experimental Bell violation yields S=2.39±0.12. The difference between the fit curve and the data points in (a–d) is due to random drifts in the piezo movement and the statistical distribution of the single-photon detections. The error bars shows the s.d. assuming a poissonian distribution for the photon statistics.

Discussion

Future quantum communication systems must work over long distances, avoid the need of a straight line between the communicating parties and fit within existing communication infrastructures. In addition, security must be based on physical principles rather than on unproven assumptions. For these reasons, energy-time entanglement-based quantum communication is, in principle, the ideal solution. However, the fact that standard setups for creating energy-time entanglement are intrinsically insecure even assuming perfect detection efficiency constitutes a fundamental hurdle. Here we have demonstrated for the first time that genuine energy-time entanglement can be distributed over long distances, thus removing one fundamental obstacle for practical and secure quantum communication with optical fibres. Note that even though polarization entanglement has also been distributed through optical fibres36,37, energy-time entanglement has the advantage of having an innate robustness to decoherence in optical fibres.

In commercial networks, remote nodes are connected with optical cables composed of many optical fibres. For an experiment, based on the hug configuration and with spatial separation between Alice and Bob, two fibres of the same cable can be used. In this case, as the phase drift acts almost equally on both fibres, it is very likely that the scheme adopted here for the stabilization of the fibre-based long interferometer can also be used. Further investigations are required in this direction. Nevertheless, our work is a first step towards practical long-distance secure quantum communication based on energy-time entanglement, as it fixes the previous security issues with all other demonstrations using Franson’s configuration.

Methods

Stabilization system

A long-coherence single-longitudinal mode continuous wave laser operating at 852 nm is used as a feedback optical signal. The feedback optical signal is combined with the pump beam on a dichroic mirror before the crystal. The FS is a commercial off-the-shelf device consisting of a 40 m long optical fibre spooled around a piezoelectric element. The feedback optical signal is detected by an amplified p-i-n photodetector in one of the outputs of the long interferometer, after being split by a dichroic mirror. In order to avoid unwanted noise generated from the control laser, three extra optical filters are employed: one bandpass 850 nm optical filter (10 nm of full width at half-maximum), placed at the output of the 852 nm laser, and two bandpass 806 nm filters in series (5 nm of full width at half-maximum) are inserted before each single-photon detector. For the sake of clarity these are not shown in Fig. 1c.

The phase setting φb applied by Bob was controlled using the set-point in the field programmable gate array electronics. It reads the optical intensity of the feedback signal, which gives information on the current relative phase between the interferometer arms. Furthermore, it calculates the derivative of the signal, to remove ambiguity arising from the phase information. With both the intensity of the signal and the derivative, the control is able to fix any constant relative phase difference between the interferometer arms. The total bandwidth of the control system including the optical components (stretcher and detector) is of ~5 kHz.

Indistinguishability between the two-photon paths

To generate the indistinguishability between the  and

and  paths, a bulk-optics delay line, with a movement range of 150 mm, is used. As it is experimentally challenging to properly balance two long paths within the two-photon coherence length (≈1 mm in our case), a previous adjustment of the 1.04 km arms was performed in an external interferometer with a Fabry–Perot laser source for a course adjustment. Then a broadband light source (a light emitting diode) was used replacing the Fabry–Perot laser to set the arm lengths to be equal within less than 1 mm. The arms were then installed in the setup, and the extra 2 m of optical fibre added in the long arm.

paths, a bulk-optics delay line, with a movement range of 150 mm, is used. As it is experimentally challenging to properly balance two long paths within the two-photon coherence length (≈1 mm in our case), a previous adjustment of the 1.04 km arms was performed in an external interferometer with a Fabry–Perot laser source for a course adjustment. Then a broadband light source (a light emitting diode) was used replacing the Fabry–Perot laser to set the arm lengths to be equal within less than 1 mm. The arms were then installed in the setup, and the extra 2 m of optical fibre added in the long arm.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Cuevas, A. et al. Long-distance distribution of genuine energy-time entanglement. Nat. Commun. 4:2871 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3871 (2013).

References

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145–195 (2002).

Lydersen, L. et al. Hacking commercial quantum cryptography systems by tailored bright illumination. Nat. Photon. 4, 686–689 (2010).

Bell, J. S. Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics: Collected Papers on Quantum Philosophy Cambridge University Press (2004).

Ekert, A. K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 661–663 (1991).

Barrett, J., Hardy, L. & Kent, A. No signaling and quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 010503 (2005).

Acín, A. et al. Device-independent security of quantum cryptography against collective attacks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 230501 (2007).

Weihs, G., Jennewein, T., Simon, C., Weinfurter, H. & Zeilinger, A. Violation of Bell’s inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5039–5043 (1998).

Giustina, M. et al. Bell violation using entangled photons without the fair sampling assumption. Nature 497, 227–230 (2013).

Christensen, B. G. et al. Detection-loophole-free test of quantum nonlocality and applications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 130406 (2013).

Smith, D. H. et al. Conclusive quantum steering with superconducting transition edge sensors. Nat. Commun. 3, 625 (2012).

Bennet, A. J. et al. Arbitrarily loss-tolerant Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen steering allowing a demonstration over 1 km of optical fibre with no detection loophole. Phys. Rev. X 2, 031003 (2012).

Wittmann, B. et al. Loophole-free Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen experiment via quantum steering. New J. Phys. 14, 053030 (2012).

Larsson, J.-Å. & Gill, R. D. Bell’s inequality and the time-coincidence loophole. Bell’s inequality and the coincidence-time loophole. Europhys. Lett. 67, 707–713 (2004).

Kofler, J., Ramelow, S., Giustina, M. & Zeilinger, A. On Bell violation using entangled photons without the fair-sampling assumption. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1307.6475 (2013).

Larsson, J. Å. et al. Bell violation with entangled photons, free of the coincidence-time loophole. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1309.0712 (2013).

Franson, J. D. Bell inequality for position and time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2205–2208 (1989).

Tapster, P. R., Rarity, J. G. & Owens, P. C. M. Violation of Bell’s inequality over 4 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1923–1926 (2004).

Tittel, W., Brendel, J., Zbinden, H. & Gisin, N. Violation of Bell inequalities by photons more than 10km apart. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3563–3566 (1998).

Brendel, J., Gisin, N., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Pulsed energy-time entangled twin-photon source for quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2594–2597 (1999).

Tittel, W., Brendel, J., Zbinden, H. & Gisin, N. Quantum cryptography using entangled photons in energy-time Bell states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4737–4740 (2000).

Marcikic, I. et al. Distribution of time-bin entangled qubits over 50 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 180502 (2004).

Salart, D., Baas, A., van Houwelingen, J. A. W., Gisin, N. & Zbinden, H. Spacelike separation in a Bell test assuming gravitationally induced collapses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 220404 (2008).

Salart, D., Baas, A., Branciard, C., Gisin, N. & Zbinden, H. Testing the speed of ‘spooky action at a distance’. Nature 454, 861–864 (2008).

Aerts, S., Kwiat, P., Larsson, J.-Å. & Żukowski, M. Two-photon Franson-type experiments and local realism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 2872–2875 (1999).

Cabello, A., Rossi, A., Vallone, G., de Martini, F. & Mataloni, P. Proposed Bell experiment with genuine energy-time entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 040401 (2009).

Clauser, J. F., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A. & Holt, R. A. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 880–884 (1969).

Franson, J. D. Inconsistency of local realistic descriptions of two-photon interferometer experiments. Phys. Rev. A. 61, 012105 (1999).

Franson, J. D. Nonclassical nature of dispersion cancellation and nonlocal interferometry. Phys. Rev. A. 80, 032119 (2009).

Larsson, J.-Å. Energy-time entanglement, elements of reality, and local realism. inAIP Conf. Proc. 1232, 115–127 (2010).

Larsson, J.-Å. A practical Trojan horse for Bell-inequality-based quantum cryptography. Quant. Inf. Comp. 2, 434–442 (2002).

Lima, G., Vallone, G., Chiuri, A., Cabello, A. & Mataloni, P. Experimental Bell-inequality violation without the postselection loophole. Phys. Rev. A. 81, 040401(R) (2010).

Vallone, G. et al. Testing Hardy’s nonlocality proof with genuine energy-time entanglement. Phys. Rev. A. 83, 042105 (2011).

Ljunggren, D. & Tengner, M. Optimal focusing for maximal collection of entangled narrow-band photon pairs into single-mode fibers. Phys. Rev. A. 72, 062301 (2005).

Meyer-Scott, E. et al. Quantum entanglement distribution with 810 nm photons through telecom fibres. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 031117 (2010).

Xavier, G. B. & von der Weid, J. P. Stable single-photon interference in a 1 km fiber-optic Mach-Zehnder interferometer with continuous phase adjustment. Opt. Lett. 36, 1764–1766 (2011).

Sauge, S. et al. Narrowband polarization-entangled photon pairs distributed over a WDM link for qubit networks. Opt. Express. 15, 6926–6933 (2007).

Hübel, H. et al. High-fidelity transmission of polarization encoded qubits from an entangled source over 100km of fiber. Opt. Express. 15, 7853–7862 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Barbieri for valuable discussions. This work was supported by the grants FONDECYT 11110115 and 1120067, CONICYT PFB08-024 and Milenio P10-030-F. A. Cuevas, G.C. and J.C. acknowledge the financial support of CONICYT, while M.F. acknowledges support of FONDECYT 1121010. A. Cabello was also supported by Project No. FIS2011-29400 (MINECO, Spain).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Cuevas, G.C., G.S. and J.C., with assistance from W.N., M.F., P.M., G.L. and G.X., performed the experiment and analysed the data. A. Cabello, P.M., G.L. and G.X. conceived and designed the experiment and wrote the paper. All authors agree to the contents of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cuevas, A., Carvacho, G., Saavedra, G. et al. Long-distance distribution of genuine energy-time entanglement. Nat Commun 4, 2871 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3871

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3871

This article is cited by

-

Photonic-chip-based dense entanglement distribution

PhotoniX (2023)

-

Quantum information processing with space-division multiplexing optical fibres

Communications Physics (2020)

-

Two-photon interference in the telecom C-band after frequency conversion of photons from remote quantum emitters

Nature Nanotechnology (2019)

-

Four-dimensional entanglement distribution over 100 km

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Generalized quantum interference of correlated photon pairs

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.