Abstract

Gate operations in a quantum information processor are generally realized by tailoring specific periods of free and driven evolution of a quantum system. Unwanted environmental noise, which may in principle be distinct during these two periods, acts to decohere the system and increase the gate error rate. Although there has been significant progress characterizing noise processes during free evolution, the corresponding driven-evolution case is more challenging as the noise being probed is also extant during the characterization protocol. Here we demonstrate the noise spectroscopy (0.1–200 MHz) of a superconducting flux qubit during driven evolution by using a robust spin-locking pulse sequence to measure relaxation (T1ρ) in the rotating frame. In the case of flux noise, we resolve spectral features due to coherent fluctuators, and further identify a signature of the 1 MHz defect in a time-domain spin–echo experiment. The driven-evolution noise spectroscopy complements free-evolution methods, enabling the means to characterize and distinguish various noise processes relevant for universal quantum control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the gate-based model of quantum computation, a quantum algorithm may be efficiently implemented on a quantum information processor by decomposing it into a finite and discrete set of coherent gate operations1. Their realization, although in detail dependent on the particular physical-qubit modality, may be broadly divided into two categories, free evolution and driven evolution, indicating the period(s) during which the desired gate operates on the system. During these two types of evolution, unwanted environmental noise acts to decohere the system and increase the gate error rate. Although process tomography may provide the complete map of the action of a gate operation, it does not characterize the noise sources, which cause fidelity degradation and which, in principle, may differ under free- and driven-evolution conditions. In contrast, the noise sensitivity of the quantum device itself, in conjunction with tailored pulse sequences, may be used to identify spectral features of the noise and thereby elucidate the underlying noise mechanisms2,3.

Dynamical decoupling protocols, for example, spin–echo and its multi-pulse extensions, have been applied to mitigate dephasing during free evolution in numerous qubit modalities, including atomic ensembles4,5 and single atoms6, spin ensembles7, diamond nitrogen-vacancy centres8,9, semiconductor quantum dots10,11, and superconducting qubits12. The spectral filtering properties13 of these and related sequences have proven a useful tool for performing free-evolution noise spectroscopy with superconducting qubits over a wide range of frequencies spanning millihertz14,15 to over 20 MHz12. Several groups have also made progress characterizing12,16,17 and mitigating18 decoherence during driven evolution. This case is more difficult in practice, however, because driven-evolution decoherence may be highly correlated with the operational errors that occur while implementing a particular protocol. Such correlations pose challenges for fault-tolerant quantum information processing, and it motivates the importance of characterizing the noise processes that are manifest while the qubit is under external drive.

Noise spectroscopy during driven evolution has been studied most extensively via Rabi nutation of the qubit between its ground and excited states, achieved by continuously driving the qubit with an oscillating field. Noise power at the Rabi frequency is inferred from the Rabi-oscillation-decay envelope, and the noise spectrum is reconstructed over the achievable range of Rabi frequencies by varying the field amplitude12,16,17 (and F. Yoshihara et al., manuscript in preparation). There are several drawbacks to this approach, however, including the Rabi experiment’s associated transverse decay, its sensitivity to low-frequency fluctuations of the Rabi frequency, the interpretation of the resultant non-exponential decay law, and the practical consideration of sampling sufficiently many points to resolve and fit accurately a decaying sinusoid oscillating at the Rabi frequency. This type of Rabi-based noise spectroscopy can, however, be generalized by preparing the qubit in an arbitrary initial state. One unique case, originating within the NMR community, is the so-called T1ρ experiment16,19,20,21,22, which measures the driven-evolution analogue to T1 relaxation. In T1ρ, the driving field is applied along an axis collinear with the qubit’s state-vector in the rotating frame, resulting in a condition called ‘spin locking.’ The main advantages of T1ρ-based noise spectroscopy are that the qubit decays longitudinally from the spin-locked state with a straightforward exponential decay law (no oscillations); the decay is dominated by noise at the spin-locking frequency and, like its T1 analogue, is relatively insensitive to broadband low-frequency noise; and it can therefore have higher accuracy over a wider frequency range than the standard Rabi-based approach.

In this work, we develop a modified T1ρ pulse sequence to perform noise spectroscopy during the driven evolution of a superconducting flux qubit. The modified pulse sequence addresses several non-idealities due primarily to 1/f-type noise that may pollute the spin-locking dynamics when using the conventional T1ρ sequence. Using this improved sequence, we measure both the flux and tunnel-coupling noise spectra during driven evolution over the frequency range 0.1–200 MHz. The observed flux-noise power spectral density (PSD) generally agrees with the 1/f dependence found independently using free-evolution noise spectroscopy12. Notably, between the experiments by Bylander et al.12 and those presented here, we thermal-cycled the device from 12 mK to 4 K and back again. With the higher accuracy afforded by the T1ρ measurement, we resolved two additional ‘bump’-like features in the spectrum, possibly due to a set of two-level systems (TLSs), for example, electron spins, that were apparently activated by the thermal cycling. We further demonstrate that the underlying noise mechanisms associated with these particular spectral features are also active during free evolution by observing their signature in a time-domain echo experiment.

Results

Device

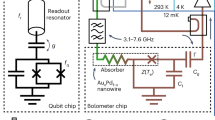

Our test device is a superconducting flux qubit (Fig. 1a), an aluminium loop interrupted by four Al-AlOx-Al Josephson junctions. When an external magnetic flux Φ≈Φ0/2 threads the loop, the qubit’s potential energy assumes a double-well profile. The wells are associated with clockwise and counterclockwise circulating currents of magnitude Ip≈180 nA and energies ±hε/2=±Ip(Φ−Φ0/2) tunable by the applied flux. These diabatic circulating-current states tunnel-couple with a strength Δ=5.4 GHz, and the resulting hybridized qubit states are manipulated using microwave pulses that couple to the qubit via an on-chip antenna. The qubit is embedded in a DC SQUID, a sensitive magnetometer which serves as the qubit readout. The device and measurement set-up is detailed further by Bylander et al.12

(a) Schematic of the flux qubit with measurement set-up. (b) Measured qubit frequency versus flux bias. (c) Analogy between free and driven evolution. Red and yellow arrows indicate the quantizing field, respectively. The longitudinal axes are highlighted by green arrows, and the transverse planes are highlighted by the blue disks. Grey arrows indicate the temperature-dependent longitudinal (T1 and T1ρ) and transverse (T2 and T2ρ) depolarization. (d) Standard three-pulse spin-locking sequence (SL-3). Green and blue indicate X- and Y-pulse, respectively. (e) Bloch sphere representation of the rotating-frame qubit dynamics under SL-3. The purple arrows are the qubit’s state polarization, while the magenta arrows indicate the driving-field orientation. The qubit is initially prepared in its ground state (I). The first π/ pulse rotates the qubit by 90° into the equatorial plane (II). The second 90°-phase-shifted continuous driving pulse of duration τ, is then aligned with the qubit state, effectively locking the qubit along X. During the pulse, the qubit undergoes relaxation in this rotating frame towards its steady state (III). The final π/

pulse rotates the qubit by 90° into the equatorial plane (II). The second 90°-phase-shifted continuous driving pulse of duration τ, is then aligned with the qubit state, effectively locking the qubit along X. During the pulse, the qubit undergoes relaxation in this rotating frame towards its steady state (III). The final π/ pulse projects the remaining polarization onto Z (=z′) for readout (IV).

pulse projects the remaining polarization onto Z (=z′) for readout (IV).

Reference frames and Hamiltonians

In the laboratory frame and within a TLS approximation, the qubit Hamiltonian is:

where  and

and  are Pauli operators. δΔ(t) and δε(t) represent random fluctuations in the effective tunnel-coupling and flux terms, respectively, and the oscillating term represents the harmonic driving field that is treated semiclassically with amplitude Arf(t), frequency vrf and phase φ. Although noise affecting the qubit physically manifests itself in the lab frame (equation 1), the longitudinal (T1 and T1ρ) and transverse (T2 and T2ρ) relaxation times for free- and driven evolution may be analogously defined in the qubit-eigenbasis and rotating frames, respectively, as described below and presented in Table 1 (also see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table S1 for detailed derivation and description). Their measurement may then be related back to the physical noise parameters in the laboratory frame.

are Pauli operators. δΔ(t) and δε(t) represent random fluctuations in the effective tunnel-coupling and flux terms, respectively, and the oscillating term represents the harmonic driving field that is treated semiclassically with amplitude Arf(t), frequency vrf and phase φ. Although noise affecting the qubit physically manifests itself in the lab frame (equation 1), the longitudinal (T1 and T1ρ) and transverse (T2 and T2ρ) relaxation times for free- and driven evolution may be analogously defined in the qubit-eigenbasis and rotating frames, respectively, as described below and presented in Table 1 (also see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table S1 for detailed derivation and description). Their measurement may then be related back to the physical noise parameters in the laboratory frame.

Decoherence during free evolution is described by transforming equation 1 to the qubit’s energy eigenbasis:

where θ=arctan(ε/Δ) is the rotation angle of the quantization axis from the lab frame, and vq= is the qubit’s frequency splitting (Fig. 1b). The standard longitudinal (T1≡1/Γ1) and transverse (T2≡1/Γ2) relaxation times are defined in this frame. In our device, T1 ≈12 μs with only a weak dependence on ε, whereas T2 ≈3 μs at ε=0 and decreases away from this point12.

is the qubit’s frequency splitting (Fig. 1b). The standard longitudinal (T1≡1/Γ1) and transverse (T2≡1/Γ2) relaxation times are defined in this frame. In our device, T1 ≈12 μs with only a weak dependence on ε, whereas T2 ≈3 μs at ε=0 and decreases away from this point12.

Decoherence during driven evolution (that is, during a constant-amplitude pulse, Arf(t)=Arf) is described by a second transformation, taking equation 2 to a reference frame rotating at the drive frequency vrf (omitting stochastic terms):

where Δv=vq−vrf is the frequency detuning between the qubit and the driving field, and vR= Arf cosθ is the Rabi frequency under resonant driving (Δv=0). Here the rotating wave approximation has been invoked by omitting the fast oscillating terms (see Supplementary Note 1 for a generalization).

Arf cosθ is the Rabi frequency under resonant driving (Δv=0). Here the rotating wave approximation has been invoked by omitting the fast oscillating terms (see Supplementary Note 1 for a generalization).

Analogy between free and driven evolution

For resonant driving along the x axis (Δv=0, φ=0), the Hamiltonian in equation 3 describes a pseudospin quantized along X with a level splitting equivalent to the Rabi frequency vR. The qubit’s Bloch vector precesses around the x axis at a rate vR, and its subtended angle depends on the initial state. That is, the driven evolution of the qubit state may be interpreted as the ‘free evolution’ of a pseudospin around a static field vR (Fig. 1c). By analogy with the conventional free-evolution T1 and T2 times, we define longitudinal and transverse depolarization times T1ρ and T2ρ for the pseudospin with respect to this new quantization axis (see Table 1). Just as T1 depends on the noise at the qubit frequency vq that is transverse to the z′ axis (equation 2), so is T1ρ determined by the noise at the pseudospin’s level splitting vR that is transverse to the x axis (equation 3). For completeness, the measurement and value of the rotating-frame decoherence time T2ρ (‘free-induction’ time in the rotating frame) is equivalent to the conventional Rabi experiment and associated decay time TRabi (Supplementary Fig. S2b). More detailed discussion about the analogy between free evolution and driven evolution in the rotating frame can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

The connection between the driven-evolution times (T1ρ, T2ρ), the free-evolution times (T1, T2) and the PSD of the physical noise terms (δΔ(t), δε(t)) is formally made using the generalized Bloch equations23,24 and the transformations between equations 1, 2, 3. The exponential relaxation rate during weak and resonant driving is

where

stands for the symmetrized PSD of λ-noise, and λϵ{Δ,ε… or x′,y′,z′…} indicates either the fluctuating part of the system Hamiltonian or the axis along which those fluctuations occur. The relaxation rate Γ1ρ arises from two terms related to noise in the qubit-eigenbasis (equation 2). The first term (Γ1 term) is associated with transverse noise along the x′ axis at frequency vq±vR (which appears as vR in the rotating frame). The second term (Γv term) is the longitudinal noise along the z′ axis at the drive frequency vR, which is directly transferred into the rotating frame. This latter term provides a direct method to extract the noise PSD at the locking Rabi frequency by measuring relaxation during driven evolution via a T1ρ experiment.

stands for the symmetrized PSD of λ-noise, and λϵ{Δ,ε… or x′,y′,z′…} indicates either the fluctuating part of the system Hamiltonian or the axis along which those fluctuations occur. The relaxation rate Γ1ρ arises from two terms related to noise in the qubit-eigenbasis (equation 2). The first term (Γ1 term) is associated with transverse noise along the x′ axis at frequency vq±vR (which appears as vR in the rotating frame). The second term (Γv term) is the longitudinal noise along the z′ axis at the drive frequency vR, which is directly transferred into the rotating frame. This latter term provides a direct method to extract the noise PSD at the locking Rabi frequency by measuring relaxation during driven evolution via a T1ρ experiment.

Advantages of T1ρ over Rabi spectroscopy

The T1ρ experiment, when utilized as a noise spectrum analyser to extract the PSD, has inherent advantages over direct Rabi-based techniques12,17 (and F. Yoshihara et al., in preparation). One major shortcoming of the Rabi method is its vulnerability to low-frequency fluctuation δvR of the effective Rabi frequency. First, the Rabi frequency is first-order sensitive to fluctuations of the driving-field amplitude δvR (proportional to δArf), whose RMS fluctuation is found in this case proportional to vR (δvR ≈0.06% vR)18. Hence, the temporal vR inhomogeneity becomes important when the driving is strong (large vR). In addition, low-frequency fluctuation of the qubit’s level splitting (δv) modulates the effective Rabi frequency to second order, adding to the inhomogeneous broadening12. The effect dominates the Rabi decay when the driving is weak enough (small vR, as the second-order contribution  /vR exceeds decay rates from other sources) (Table 1). These two effects are analogous to the scenarios of free-evolution dephasing due to low-frequency noise via linear and quadratic coupling, respectively16. In contrast, the locking dynamics in the T1ρ experiment largely reduce its sensitivity to these fluctuations, and thus substantially improves the accuracy of the extracted noise PSD, especially at both high and low-frequency regimes.

/vR exceeds decay rates from other sources) (Table 1). These two effects are analogous to the scenarios of free-evolution dephasing due to low-frequency noise via linear and quadratic coupling, respectively16. In contrast, the locking dynamics in the T1ρ experiment largely reduce its sensitivity to these fluctuations, and thus substantially improves the accuracy of the extracted noise PSD, especially at both high and low-frequency regimes.

In addition, T1ρ has a simple exponential decay law, whereas the Rabi decay law can be complicated by its sinusoidal nutation in conjunction with a non-exponential decay envelope related to its sensitivity to low-frequency noise (see Table 1), both of which pose a challenge to high-precision fitting. A T1ρ measurement requires far fewer datapoints than would a Rabi decay envelope on a sinusoid oscillating at the Rabi frequency. These properties make the T1ρ method more accurate and experimentally efficient.

Conventional T1ρ sequence

The measurement of the rotating-frame relaxation time T1ρ begins by preparing the qubit state to be either parallel or anti-parallel with X (collinear with the driving field), corresponding to the pseudospin’s ground and excited state, respectively. This results in the so-called ‘spin-locking’ condition, a reference to the pseudospin remaining aligned in the absence of noise with the static driving field vR in equation 3 (see Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. S2a). The measurement of the relaxation time from the spin-locked condition to a depolarized steady-state is the so-called T1ρ experiment.

The original T1ρ sequence as developed in NMR and applied to superconducting qubits was a three-pulse sequence25, two π/2 pulses separated by a 90°-phase-shifted continuous driving pulse (labelled here ‘SL-3’, see Fig. 1d). The phase shift is implemented by altering the driving-field phase φ via standard IQ-mixing techniques. The dynamics can be visualized with the assistance of the Bloch sphere within the rotating frame (Fig. 1e). For convenience, we use {X,Y,Z} to denote rotating-frame coordinates, pulse phase and qubit states. The first  pulse (bar indicates negative or 180-degrees-rotated orientation) brings the qubit from its ground state to the equator, parallel with X (step I). The driving field is then applied along X and thereby aligned with the qubit state, so that the qubit is effectively locked in this orientation and experiences relaxation Γ1ρ only (steps II and III). After a finite duration τ, the remaining polarization along X is projected, by the last

pulse (bar indicates negative or 180-degrees-rotated orientation) brings the qubit from its ground state to the equator, parallel with X (step I). The driving field is then applied along X and thereby aligned with the qubit state, so that the qubit is effectively locked in this orientation and experiences relaxation Γ1ρ only (steps II and III). After a finite duration τ, the remaining polarization along X is projected, by the last  pulse, back along Z for readout (step IV). The long-time, steady-state population carries no net X-polarization, because the device is operated in the limit vR<<kBT/h=1.3 GHz, where T≈65 mK is the effective device temperature obtained by measuring the SQUID’s switching-current distribution. The

pulse, back along Z for readout (step IV). The long-time, steady-state population carries no net X-polarization, because the device is operated in the limit vR<<kBT/h=1.3 GHz, where T≈65 mK is the effective device temperature obtained by measuring the SQUID’s switching-current distribution. The  –X–

–X– phase order applied here and the X–Y–X one by Collin et al.25 are effectively the same, as only the relative phase is important. We repeat the same sequence on a nominally identically prepared system a few thousand times to improve state estimation. Hence, decoherence of this system should be understood in the sense of a temporal ensemble average.

phase order applied here and the X–Y–X one by Collin et al.25 are effectively the same, as only the relative phase is important. We repeat the same sequence on a nominally identically prepared system a few thousand times to improve state estimation. Hence, decoherence of this system should be understood in the sense of a temporal ensemble average.

Modified T1ρ sequence

In solid-state systems, the recorded T1ρ decay signal using the original (SL-3) sequence may suffer from several types of system imperfection, in particular, signal distortion due to low-frequency noise via other channels. One example of a measured T1ρ trace is shown in Fig. 2b (brown trace). Another example can be found in the studies of Collin et al.25, an early demonstration of spin-locking implemented on a quantronium qubit. A prominent feature in these examples is the presence of unwanted Rabi-frequency oscillations on the back of an otherwise exponential decay function. We excluded the possibility of a constant frequency detuning in our experiment, which could effectively separate the driving field and qubit state during the locking period and lead to oscillations. Rather, we determined that the oscillations were due to dephasing during the intervals between adjacent pulses. In our experiments, we use Gaussian pulses with ~10 ns width for the π/2 pulses and Gaussian rise-and-fall for the long driving pulse. To clearly separate pulses, there is a practically unavoidable duration of free evolution between pulses (Fig. 1d). Depending on the length τ of the second pulse, phase diffusion accumulated during the first interval will sometimes be doubled (for vRτ=1,2,3…), and sometimes be refocused (for vRτ= , 1

, 1 , 2

, 2 …), producing those oscillations. In the presence of this noise, the locking protocol is compromised to a differing degree for the temporal ensemble elements, making the observed decay a complicated combination of precession, relaxation and decoherence processes. To correct for it, we developed a modified five-pulse sequence (labelled ‘SL-5a,’ see Fig. 2a), which adds one πX pulse in the middle of each interval in SL-3. The added pulses refocus the phase diffusion as is done in a spin–echo sequence26. Relaxation obtained using SL-5a is shown in Fig. 2b, and it shows a clear improvement (no oscillation) over SL-3.

…), producing those oscillations. In the presence of this noise, the locking protocol is compromised to a differing degree for the temporal ensemble elements, making the observed decay a complicated combination of precession, relaxation and decoherence processes. To correct for it, we developed a modified five-pulse sequence (labelled ‘SL-5a,’ see Fig. 2a), which adds one πX pulse in the middle of each interval in SL-3. The added pulses refocus the phase diffusion as is done in a spin–echo sequence26. Relaxation obtained using SL-5a is shown in Fig. 2b, and it shows a clear improvement (no oscillation) over SL-3.

(a) Modified five-pulse sequences (SL-5a and SL-5b), robust in the presence of δε and δΔ low-frequency noise. (b) Comparison of measured signals by SL-3 (brown) and SL-5a (blue). Both traces are taken at ε=192 MHz and vR=3 MHz. PSW is the measured switching probability of the readout SQUID, and is linear with the qubit’s state population. (c) Comparison of measured signals by SL-5a (blue), SL-5b (red) and their average (purple). Both traces are taken at ε=960 MHz and vR=24 MHz. The data are taken in an interleaved order between blue and red traces. (d) Cross-section sketch of the qubit dynamics under the SL-5a and SL-5b protocols, with the driving field (magenta arrow) tilted by an angle η (η>0 in this example) due to slow fluctuations of the frequency detuning. On the left are the qubit states right before the locking pulse; on the right, their relaxation paths during the locking period are indicated by the dashed lines. The steady-state solution (the contacting point of blue and red dash lines) deviates away from  =0 when η≠0.

=0 when η≠0.

In several measured traces, we observe a second type of signal distortion—random fluctuations at the few-percent level on the exponential signal, and at a time scale of minutes or tens of minutes—for example, Fig. 2c (blue trace). As we describe in detail below, low-frequency fluctuations of the frequency detuning result in the ‘shivering’ of the effective Rabi field and, thereby, fluctuations in the observed decay signal. We first describe how we corrected the distortion, and then explain its origin. The solution is to use a complementary pulse sequence (labelled ‘SL-5b,’ see Fig. 2a) together with SL-5a. The new sequence is nominally identical to SL-5a, except that we replace the two  pulses with two π/2Y pulses, such that the qubit Bloch vector is anti-parallel with the driving axis for SL-5b. Ideally, both sequences should give the same decay function. However, when we apply the sequences in an interleaved sampling order (inner loop: alternate between SL-5a and SL-5b; outer loop: step τ), the anti-symmetry of the signal fluctuation, slow compared with the collection time at each value τ, is captured by the twin sequences, as shown by the example in Fig. 2c. We then recover the smooth exponential decay by taking the average of the two traces.

pulses with two π/2Y pulses, such that the qubit Bloch vector is anti-parallel with the driving axis for SL-5b. Ideally, both sequences should give the same decay function. However, when we apply the sequences in an interleaved sampling order (inner loop: alternate between SL-5a and SL-5b; outer loop: step τ), the anti-symmetry of the signal fluctuation, slow compared with the collection time at each value τ, is captured by the twin sequences, as shown by the example in Fig. 2c. We then recover the smooth exponential decay by taking the average of the two traces.

Our ability to recover a smooth exponential decay is closely related to the ultra-slow (~minutes) fluctuation of frequency detuning δv. First, the occurrence of the signal distortion at large τ indicates a deviation of the steady-state population from zero X-polarization. Assuming small detuning (Δv<<vR), to first order, the steady-state X-polarization24 (and Supplementary Note 1), in the practical limit vR<<kBT/h<<vq, is

where η=arctan(Δv/vR) is the angle of the driving field with respect to X due to frequency detuning (see Fig. 2d). Equation 6 is applicable to both SL-5a and SL-5b, but the difference in the last back-projection pulse gives rise to a differential signal response to the non-zero X-polarization. Therefore, fluctuation of the frequency detuning, to first order, causes fluctuation of the steady-state longitudinal polarization and the anti-symmetric feature of the traces in Fig. 2c. The relaxation dynamics in both sequences with finite detuning are sketched in the right panel of Fig. 2d. Ignoring the process at small τ where the much faster T2ρ process is involved, the normalized decay signal, to first order of η, can be approximated as Pa(τ)= for SL-5a, and Pb(τ)=

for SL-5a, and Pb(τ)= for SL-5b. The average P(τ)=

for SL-5b. The average P(τ)= becomes independent of detuning, and recovers the underlying relaxation signal.

becomes independent of detuning, and recovers the underlying relaxation signal.

Noise spectroscopy during driven evolution

We use the modified T1ρ pulse sequence to implement noise spectroscopy during driven evolution (Fig. 3). To derive the Δ-noise PSD, we perform a driven-evolution T1ρ measurement for various vR at ε=0, where the qubit is first-order insensitive to ε noise, as well as the standard (free-evolution) inversion-recovery T1-measurement26. Both T1 and T1ρ traces are fit to extract the exponential decay rates Γ1 and Γ1ρ, which give the Δ-noise PSD by SΔ(vR)=Sz′(vR)=2Γ1ρ−Γ1. For ε-noise PSD, we perform the same experiments at ε≠0, where the qubit becomes predominantly sensitive to ε noise. We then have Sε(vR)=[Sz′(vR)−cos2θSΔ(vR)]/sin2θ=[2Γ1ρ−Γ1−cos2θSΔ(vR)]/sin2θ, where SΔ(vR) is previously measured. The locking Rabi frequency, vR, is determined by measuring Rabi oscillations with the same driving-field amplitude. The lower limit (~100 kHz) of the spectrum is determined by the Δv inhomogeneity  , which breaks the locking condition when driving is too weak. On the other hand, an undetermined effect (presumably heating due to strong driving), which distorts the SQUID’s switching-current distribution, prevents us from probing higher frequency than ~200 MHz. We believe the limitation is unrelated to the SQUID plasma mode, which is around ~2.3 GHz for this device.

, which breaks the locking condition when driving is too weak. On the other hand, an undetermined effect (presumably heating due to strong driving), which distorts the SQUID’s switching-current distribution, prevents us from probing higher frequency than ~200 MHz. We believe the limitation is unrelated to the SQUID plasma mode, which is around ~2.3 GHz for this device.

ε (red dots) and Δ (blue dots) noise spectroscopy by the T1ρ method. Here, previous results on ε noise by the CPMG (grey dots) and Rabi (green squares) methods measured on the same device are plotted for comparison. From the fitting results, the error rate in the worst case is about 30% for ε noise, and 70% for Δ noise. Previous experiments and the T1ρ experiment were separated by 6 months and a 4-K warm-up. The red and blue solid lines are the 1/fα power laws, extrapolated from separate low-frequency noise measurements14. The black line represents the function S′(f)=A/f0.9+S1(f;F1,W1)+S2(f;F2,W2), where (f;F,W)=W2/((f−F)2+W2), and A=(2π0.65 × 106)2 (rad s−1)2, S1=7.0 × 108 rad s−1, F1=1.05 MHz, W1=0.25 MHz, S2=1.2 × 107 rad s−1, F2=20 MHz, W2=25 MHz.

In this device, the measured Δ-noise spectrum is generally white. As the extrapolated 1/f Δ-noise from low-frequency measurements crosses the white noise level around the lower limit, we are unable to determine whether the 1/f noise extends to this regime or has a cutoff14. The noise could be due to Johnson noise from charge or critical current fluctuations, or due to thermal photon noise27 originating from the LC resonator associated with the readout SQUID, which inductively couples to the qubit (Fig. 1a).

The ε-noise spectrum exhibits a 1/fα dependence with α=0.9, a value that generally agrees with independently measured free-evolution noise spectroscopy using a Ramsey (1 mHz–100 Hz)14 and Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG; 0.1–20 MHz) approach12. Although not necessarily a universal result, this suggests that driven evolution does not activate ε-noise sources for this device. In general, the T1ρ spectroscopy confirms these results with better accuracy and extends the frequency range by 5x (presumably limited in this device by a heating effect at high driving fields). Note that measuring at higher frequency (0.1–1 GHz) is feasible in principle by using this technique.

Spectral and temporal signatures of coherent TLSs

In contrast to previous free-evolution measurements, we observe on the 1/f trend two clear ‘bump-like’ features, one around 1 MHz and the other around 20 MHz. These features appeared after thermal-cycling the device from base temperature to 4.2 K and back again, which likely activated the fluctuators. The one at 1 MHz has a clear peak above the general 1/f background. This excludes the possibility of random telegraph noise (RTN), possibly generated by some microscopic two-level fluctuators, as the cause of this bump, as RTN would produce a Lorentzian spectrum centred at zero frequency28,29. To fit the main features, we assume that the ε-noise PSD is a combination of the 1/f0.9 line and two Lorentzians. Both bumps are better fit to Lorentzians centred around 1 and 20 MHz than those centred at zero frequency. One example is shown by the black line in Fig. 3.

We find a signature of the 1 MHz bump feature in a free-evolution, time-domain echo experiment. Figure 4 shows the spin–echo phase-decay as measured at several flux-bias points where the qubit coherence is mostly limited by ε noise. Under a Gaussian-noise assumption, the echo sequence is most sensitive to the noise whose frequency is about the inverse of the total free-evolution time of the sequence. The echo-decay functions all exhibit a clear ‘dip’ feature around 1 μs, corresponding to the spectral feature around 1 MHz. To model this result, we use the previously assumed PSD function S′(f) (1/f0.9 plus two Lorentzians) with tunable parameters to reproduce the echo-decay signal by the filter function method12,16,30. The agreement is good, and bump parameters estimated from the temporal echo measurement are within 30% of a direct fit to the driven-evolution spectral data. In general, we are able to predict the phase decay from the T1ρ spectroscopy results, and, in turn, justify the performance of the T1ρ spectroscopy method on a superconducting qubit. In the case of the 20-MHz Lorentzian, simulations indicate that the echo signature corresponding to this broad, relatively small feature in the noise spectrum would yield only a small deviation from the spin–echo phase-decay function with no discernable ‘dip.’ The temporal resolution in Fig. 4 is furthermore insufficient to resolve such a deviation. We note that on a subsequent cooldown, with the qubit exhibiting a similarly small spectral feature, we did observe a small distortion (but no ‘dip’) in the expected spin–echo phase-decay function.

Echo phase-memory decay (dots) measured at ε=256 MHz (red), 320 MHz (green) and 384 MHz (blue), and corresponding simulation (solid lines) with assumed flux-noise PSD function, S′(f)=A/f0.9+S1L(f;F1W1), where A=(2π0.9 × 106)2 (rad s−1)2, S1=9.0 × 108 rad s−1, F1=1.25 MHz, W1=0.35 MHz. The temporal signature of the Lorentzian at 1 MHz is essentially independent of the ε bias. Inset is the echo pulse sequence. Here, τ is the total free evolution time in the sequence. Note that the 20 MHz bump has little influence at these bias points.

It is possible that the observed Lorentzian bumps are generated by two sets of coherent TLSs31, such as electron spins. In a magnetic environment, each spin executes Larmor precession at a frequency proportional to its local field. Its transverse component couples to the qubit’s flux degree of freedom with a strength depending on geometric relations among the device, the field and the spin32, and adds to a net fluctuating flux whose PSD reflects the spectral (Larmor frequency) distribution of spins, even though the ensemble has already lost its coherence. The width of the Lorentzian indicates in part the field inhomogeneity. Assuming uncorrelated surface electron spins and an average coupling strength of 2.7 × 10−8 Φ0·  from simulation, both Lorentzian bumps correspond to ~106 spins. The number scales down in the presence of a high degree of spin order33. Moreover, if we assume the spins feel the same magnetic field as the qubit, about 0.5 mT (B0=Φ/AL, where Φ=Φ0/2 is the flux through the qubit loop and AL ≈2 μm2 is the loop size), the corresponding electron-spin Larmor frequency is 14 MHz. This is only a rough estimate, as screening due to superconducting metal may lead to a large variation of the field at various locations in the vicinity of the metal surface, and other locations for these spins, for example, the superconductor-insulator boundary34 and substrate, are also possible. Nonetheless, the crude estimate is consistent with our observations.

from simulation, both Lorentzian bumps correspond to ~106 spins. The number scales down in the presence of a high degree of spin order33. Moreover, if we assume the spins feel the same magnetic field as the qubit, about 0.5 mT (B0=Φ/AL, where Φ=Φ0/2 is the flux through the qubit loop and AL ≈2 μm2 is the loop size), the corresponding electron-spin Larmor frequency is 14 MHz. This is only a rough estimate, as screening due to superconducting metal may lead to a large variation of the field at various locations in the vicinity of the metal surface, and other locations for these spins, for example, the superconductor-insulator boundary34 and substrate, are also possible. Nonetheless, the crude estimate is consistent with our observations.

Discussion

The modified T1ρ method presented here, in conjunction with existing free-evolution spectroscopy methods, enables the characterization of the noise sources relevant for both driven- and free-evolution quantum control methods. Although many noise sources may be manifest similarly during both conditions, in principle, the noise in these two cases need not be identical. For example, driven evolution may activate certain noise sources that are otherwise dormant during free-evolution. In this demonstration with a flux qubit, the flux and tunnel-coupling noise spectra reveal more detailed information and cover a wider frequency range, a 10 × increase in this device, as compared with our previous free-evolution (CPMG spectroscopy) and driven evolution (Rabi spectroscopy) methods12. We observed the spectral features of two sets of coherent TLSs in the environment, possibly due to effective electron spins on the metal surface, which are active during driven evolution. We could furthermore observe a temporal signature of one of these fluctuators in a free-evolution echo experiment, indicating that it is active during both driven and free evolution. This type of noise characterization serves as an important step towards the engineered mitigation of decoherence through improved materials, fabrication, control sequences and qubit design. Our modifications to the T1ρ pulse sequence target the unwanted effects of low-frequency noise, opening this method to the multiple qubit modalities that are subject to such noise.

Methods

Description of the qubit

We fabricated our device at NEC, using the standard Dolan angle-evaporation deposition process of Al–AlOx–Al on a SiO2/Si wafer.

Our persistent-current qubit12,35 consists of a superconducting loop with diameter d ~2 μm, interrupted by four Josephson junctions. Three of the junctions each have the Josephson energy EJ=h × 210 GHz, and charging energy EC=h × 4 GHz; the fourth is smaller by a factor α=0.54.

The qubit is embedded in a hysteretic DC SQUID, a sensitive magnetometer, which is used for the qubit readout. It has a critical current Ic,sq=4.5 μA; normal resistance RN=0.25 kΩ; mutual qubit–SQUID inductance MQ–S=21 pH; on-chip shunt capacitors Csh ≈10 pF, inductors Lsq ≈0.1 nH, and bias resistors RI=1 kΩ and RV=1 kΩ. The shunt capacitors bring the plasma frequency down to fp=2.1 GHz, which is much higher than the frequencies of the coherent fluctuators presumably related to the frequency- and time-domain results.

Pulse generation and calibration

The r.f. microwave pulses are created by mixing the in-phase and quadrature pulse envelopes, generated by a Tektronix 5014 Arbitrary Waveform Generator, with a continuous wave, provided by an Agilent E8267D PSG Vector Signal Generator. We use the internal I/Q mixer of the PSG for the envelope mixing. All pulses are further gated in order to eliminate leakage.

Imperfections in the electronics and coaxial cables will cause pulse distortions, especially for short pulses (a few nanoseconds long). To ensure that the pulses we send to the cryostat are free from distortions, we first determine the transfer function Hext with a high-speed oscilloscope, and then use  to correct for imperfections in the arbitrary waveform generator and in the I/Q mixers36. This set-up allows us to create well-defined Gaussian-shaped microwave pulses with pulse widths as short as 2.5 ns.

to correct for imperfections in the arbitrary waveform generator and in the I/Q mixers36. This set-up allows us to create well-defined Gaussian-shaped microwave pulses with pulse widths as short as 2.5 ns.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yan, F. et al. Rotating-frame relaxation as a noise spectrum analyser of a superconducting qubit undergoing driven evolution. Nat. Commun. 4:2337 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3337 (2013).

References

Dawson, C. M. & Nielsen, M. A. The Solovay-Kitaev Algorithm Preprint athttp:/arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0505030 (2005).

Slichter, C. P. Principles of Magnetic Resonance 3rd edn Springer: New York, (1990).

Schoelkopf, R. J., Clerk, A. A., Girvin, S. M., Lehnert, K. W. & Devoret, M. H. Quantum Noise in Mesoscopic Physics (Ed Nazarov Y. V. 175–203Kluwer: Dordrecht, (2002).

Biercuk, M. J. et al. Optimized dynamical decoupling in a model quantum memory. Nature 458, 996–1000 (2009).

Sagi, Y., Almog, I. & Davidson, N. Process tomography of dynamical decoupling in a dense cold atomic ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 053201 (2010).

Szwer, D. J., Webster, S. C., Steane, A. M. & Lucas, D. M. Keeping a single qubit alive by experimental dynamic decoupling. J. Phys. B Atom. Mol. Optic. Phys. 44, 025501 (2011).

Du, J. et al. Preserving electron spin coherence in solids by optimal dynamical decoupling. Nature 461, 1265–1268 (2009).

de Lange, G., Wang, Z. H., Rist, D., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Universal dynamical decoupling of a single solid-state spin from a spin bath. Science 330, 60–63 (2010).

Ryan, C. A., Hodges, J. S. & Cory, D. G. Robust decoupling techniques to extend quantum coherence in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 200402 (2010).

Barthel, C., Medford, J., Marcus, C. M., Hanson, M. P. & Gossard, A. C. Interlaced dynamical decoupling and coherent operation of a singlet-triplet qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 266808 (2010).

Bluhm, H. et al. Dephasing time of gaas electron-spin qubits coupled to a nuclear bath exceeding 200s. Nat. Phys. 7, 109–113 (2011).

Bylander, J. et al. Noise spectroscopy through dynamical decoupling with a superconducting flux qubit. Nat. Phys. 7, 565–570 (2011).

Biercuk, M. J. et al. Experimental uhrig dynamical decoupling using trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 79, 062324 (2009).

Yan, F. et al. Spectroscopy of low-frequency noise and its temperature dependence in a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. B 85, 174521 (2012).

Sank, D. et al. Flux noise probed with real time qubit tomography in a josephson phase qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 067001 (2012).

Ithier, G. et al. Decoherence in a superconducting quantum bit circuit. Phys. Rev. B 72, 134519 (2005).

Slichter, D. H. et al. Measurement-induced qubit state mixing in circuit qed from up-converted dephasing noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 153601 (2012).

Gustavsson, S. et al. Driven dynamics and rotary echo of a qubit tunably coupled to a harmonic oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 170503 (2012).

Slichter, C. P. & Ailion, D. Low-field relaxation and the study of ultraslow atomic motions by magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. 135, A1099–A1110 (1964).

Ailion, D. C. & Slichter, C. P. Observation of ultra-slow translational diffusion in metallic lithium by magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. 137, A235–A245 (1965).

Look, D. C. & Lowe, I. J. Nuclear magnetic dipole---dipole relaxation along the static and rotating magnetic fields: application to gypsum. J. Chem. Phys. 44, 2995–3000 (1966).

Loretz, M., Rosskopf, T. & Degen, C. L. Radio-frequency magnetometry using a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 017602 (2013).

Smirnov, A. Y. Decoherence and relaxation of a quantum bit in the presence of rabi oscillations. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155104 (2003).

Geva, E., Kosloff, R. & Skinner, J. L. On the relaxation of a two-level system driven by a strong electromagnetic field. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 8541–8561 (1995).

Collin, E. et al. NMR-like control of a quantum bit superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 157005 (2004).

Chiorescu, I., Nakamura, Y., Harmans, C. J. P. M. & Mooij, J. E. Coherent quantum dynamics of a superconducting flux qubit. Science 299, 1869–1871 (2003).

Bertet, P. et al. Dephasing of a superconducting qubit induced by photon noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 257002 (2005).

Galperin, Y. M., Altshuler, B. L., Bergli, J. & Shantsev, D. V. Non-gaussian low-frequency noise as a source of qubit decoherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 097009 (2006).

Paladino, E., Faoro, L., Falci, G. & Fazio, R. Decoherence and 1/f noise in Josephson qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 228304 (2002).

Cywiński, L., Lutchyn, R. M., Nave, C. P. & Das Sarma, S. How to enhance dephasing time in superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. B 77, 174509 (2008).

Shnirman, A., Schön, G., Martin, I. & Makhlin, Y. Low- and high-frequency noise from coherent two-level systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 127002 (2005).

Koch, R. H., DiVincenzo, D. P. & Clarke, J. Model for 1/f flux noise in squids and qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 267003 (2007).

Sendelbach, S., Hover, D., Mück, M. & McDermott, R. Complex inductance, excess noise, and surface magnetism in dc squids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 117001 (2009).

Faoro, L. & Ioffe, L. B. Microscopic origin of low-frequency flux noise in Josephson circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 227005 (2008).

Yoshihara, F., Harrabi, K., Niskanen, A. O., Nakamura, Y. & Tsai, J. S. Decoherence of flux qubits due to 1/f flux noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 167001 (2006).

Gustavsson, S. et al. Improving quantum gate fidelities by using a qubit to measure microwave pulse distortions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 040502 (2013).

Astafiev, O., Pashkin, Y. A., Nakamura, Y., Yamamoto, T. & Tsai, J. S. Quantum noise in the Josephson charge qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 267007 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate A. Kerman, P. Krantz, L. Levitov, S. Lloyd and T. Yamamoto for helpful discussions and K. Harrabi for assistance with device fabrication. We thank R. Wu for support in this work. This work was sponsored in part by the US Government, the Laboratory for Physical Sciences, the US Army Research Office (W911NF-12-1-0036), the National Science Foundation (PHY-1005373), the Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST), NICT Commissioned Research, MEXT kakenhi ‘Quantum Cybernetics’, Project for Developing Innovation Systems of MEXT. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily endorsed by the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Yoshihara and Y.N. designed and fabricated the device. F. Yan, S.G. and J.B. performed the experiments and contributed to the software infrastructure. F. Yan analysed the data. F. Yan and W.D.O. wrote the paper with feedback from all authors. W.D.O., D.G.C. and T.P.O. supervised the project. All authors contributed to discussions during the conception, execution and interpretation of the experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S2, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References (PDF 364 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, F., Gustavsson, S., Bylander, J. et al. Rotating-frame relaxation as a noise spectrum analyser of a superconducting qubit undergoing driven evolution. Nat Commun 4, 2337 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3337

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3337

This article is cited by

-

Relaxation of stationary states on a quantum computer yields a unique spectroscopic fingerprint of the computer’s noise

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Quantum nonlinear spectroscopy of single nuclear spins

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Effects of surface treatments on flux tunable transmon qubits

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Multi-level quantum noise spectroscopy

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Floquet prethermalization in dipolar spin chains

Nature Physics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.