Abstract

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)–derived cell lines are the preferred host cells for the production of therapeutic proteins. Here we present a draft genomic sequence of the CHO-K1 ancestral cell line. The assembly comprises 2.45 Gb of genomic sequence, with 24,383 predicted genes. We associate most of the assembled scaffolds with 21 chromosomes isolated by microfluidics to identify chromosomal locations of genes. Furthermore, we investigate genes involved in glycosylation, which affect therapeutic protein quality, and viral susceptibility genes, which are relevant to cell engineering and regulatory concerns. Homologs of most human glycosylation-associated genes are present in the CHO-K1 genome, although 141 of these homologs are not expressed under exponential growth conditions. Many important viral entry genes are also present in the genome but not expressed, which may explain the unusual viral resistance property of CHO cell lines. We discuss how the availability of this genome sequence may facilitate genome-scale science for the optimization of biopharmaceutical protein production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Recombinant therapeutic proteins were introduced >20 years ago and now generate >$99 billion in annual revenue from a broad range of products, including monoclonal antibodies, growth factors, hormones, blood factors, interferons and enzymes1. For these biopharmaceuticals, CHO-derived cell lines are the preferred host expression systems because of their advantages in producing complex therapeutics and manufacturing adaptability. CHO cells can be genetically manipulated and grown either as adherent cells or in suspension. Methods for cell transfection, gene amplification and clone selection in CHO cells are well characterized and widely used. Furthermore, CHO cells have an established history of regulatory approval for recombinant protein expression. Most importantly, these cells perform human-compatible, post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation), thereby improving therapeutic efficacy, protein longevity and reducing safety concerns. Various cell-line engineering strategies have been developed for CHO cells to enhance post-translational modifications, such as antibody glycosylation and protein sialylation2. As a result, CHO cell lines now play a dominant role in bioprocessing research and the development of therapeutic biopharmaceuticals, delivering up to several grams per liter of these products in highly optimized production processes3.

The genome sequences of CHO cell lines represent useful tools that have been unavailable to the bioprocessing community. Thus, applying genome-scale techniques to generate hyperproductive cell lines has been restricted to using expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and the potential of the 'omic technologies has not been fully realized4. To address this, we present a public draft genome sequence and comprehensive annotation of the ancestral CHO-K1 cell line. We investigate the CHO-K1 genome and transcriptome for insights into protein glycosylation and viral susceptibility because these processes affect the yield and quality of therapeutic protein production.

We note that the genomes of cell lines derived from CHO-K1 over the past few decades may contain large-scale rearrangements and that even clonal populations are known to diverge into heterogeneous subpopulations5,6. Thus, we anticipate that further analyses and sequencing studies with other clonal populations and cell lines will be required. Nevertheless, the dissemination of this ancestral CHO genome sequence should be a valuable public resource.

Results

De novo sequencing and assembly

Paired-end Illumina reads of varying insert sizes were used for the de novo assembly of CHO-K1 (Supplementary Table 1). Using the assembler SOAPdenovo7 (Online Methods), 2.45 Gb of the genome was assembled with a contig N50 of 38,289 bp and scaffold N50 of 1.115 Mb, with <3.3% gaps (Table 1; the N50 contig (scaffold) size is the length of the smallest contig (scaffold) S in the sorted list of all contigs (scaffolds) where the cumulative length from the largest contig to contig S is at least 50% of the total assembly length8). The CHO-K1 genome size was estimated to be 2.6 Gb using the k-mer estimation method (Supplementary Figs. 1–3 for distributions of sequencing depth and GC content.).

To assign scaffolds to chromosomes, we isolated and amplified individual chromosomes from single molecules using a microfluidic device (Online Methods)9. Each chromosome preparation was amplified, barcoded and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq(2000) (2 × 100 bp reads). The reads from each chromosome preparation were aligned to the assembled scaffolds and the frequency of paired-end reads aligning from each chromosome preparation was computed and normalized. Metrics derived from the normalized frequencies were used for assigning scaffolds to a particular chromosome preparation (Supplementary Notes). All of the longest scaffolds that represent 50% of the assembly (top N50 scaffolds) had chromosome reads mapping to them; 68% of the top N50 scaffolds could be unambiguously mapped to unique chromosome preparations (Table 1).

Different chromosomal counts have been reported for the CHO-K1 karyotype10, presumably due to its genomic instability. To find evidence of multiple or duplicate chromosomes across the 22 sample preparations, we used the frequency of the paired-end reads aligning from each chromosome preparation to compute the correlation between the N50 scaffolds (Supplementary Notes). Scaffolds that are from the same chromosome will be highly correlated owing to physical connection. Clustering of this correlation matrix revealed 21 large, discrete noninteracting blocks, which can be interpreted as the chromosomes containing the respective scaffolds (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Notes). Consistent with this result, classical karyotyping found 21 chromosomes in CHO-K1 (Fig. 1b and Online Methods).

(a) Chromosomal preparations from CHO-K1 were sequenced and the reads were aligned to the scaffolds. For each of the N50 scaffolds, a vector was used to represent the read alignments in the 22 preparations. Using this metric, a correlation matrix was generated between all the N50 scaffolds. Upon clustering the matrix, 21 clusters of highly correlated scaffolds emerged, suggesting that the scaffolds are associated with 21 chromosomes in CHO-K1. (b) Classical karyotyping of CHO-K1 reveals 21 chromosomes.

Repeat features in the CHO-K1 genome

Approximately 37.79% of the CHO-K1 genome is made up of transposable elements, as estimated from a combination of de novo repeat identification using RepeatModeller and analysis against the Repbase library11,12,13. This fraction of repeats is comparable to that in the mouse genome (37%) and lower than that in the human genome (46%). These transposable elements were classified into various categories (Supplementary Tables 2–4). The fraction of tandem repeats in the CHO genome (2.7%) is similar to that in rat (2.9%) and mouse (3.3%) but higher than that in human (1.5%). In summary, the repeat features of the CHO genome are more similar to those of the rodent genomes than of the human genome. This observation is consistent with earlier reports in which the mouse and rat genomes were shown to have a higher fraction of repeats compared to other mammals, especially primates14,15,16.

Gene prediction and annotation

To predict genes in the CHO-K1 genome, we used a combination of de novo gene-prediction programs and homology-based methods. The predicted gene models were reconciled using the GLEAN algorithm17. We also generated 10.8 Gb of transcriptome sequence data from exponentially growing CHO-K1 cells cultured in F-12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS, and used these data to improve gene prediction by suggesting additional transcribed genes in CHO-K1 that were missed by the gene prediction methods (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The final gene set comprises 24,383 predicted genes, 29,291 transcripts and 416 noncoding RNAs (Supplementary Notes and Supplementary Tables 7–10). Many of the predicted 24,383 genes have homologs in human (19,711), mouse (20,612) and rat (21,229) (see Supplementary Notes for comparative analysis). The predicted proteins were functionally annotated using Swissprot, Gene Ontology (GO), TrEMBL, InterPro and KEGG. In all, 83% of predicted CHO-K1 proteins were functionally annotated ((Supplementary Table 11) and orthologous clusters were analyzed (Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Figs. 4–6 and Supplementary Table 12)). When compared to human, mouse and rat, the distribution of CHO GO class assignments shows significant coverage (that is, >50% of the instances in mouse and significantly enriched, P < 0.01) of classes involved in translation, metabolism and protein modification (Fig. 2). On the other hand, classes for which few genes were identified (that is, <1% of the instances in human and mouse and significantly depleted, P < 0.01) included behavior, embryo development and anatomical structure morphogenesis. Taken together, the GO classes that had the least coverage in the CHO-K1 genome may be less relevant for a cell line (Fig. 2).

For each GOslim biological process category, the fraction of all GO terms in that category is shown for human, mouse, rat and CHO genomes. GOslim classes that are significantly enriched and show the highest and lowest coverage of human and mouse genes in the CHO genome are highlighted in red (*) and green (**), respectively. P value cutoff and coverage in human and mouse were used to determine significance.

CHO-K1 genes involved in protein glycosylation pathways

The therapeutic proteins secreted by CHO cells often include post-translational modifications including N- or O-linked glycosylation. For some of these proteins, differential glycosylation can substantially affect functional activity and/or in vivo circulatory half-life18. Furthermore, such modifications can induce immune responses if they differ from native human glycans. Therefore a genome-scale assessment of CHO glycosylation is important in the understanding of CHO-derived glycoprotein quality.

Out of 300 human genes associated with glycan synthesis and degradation, only three genes (ALG13, CHST7 and CHST13) lack homologs in the CHO-K1 genome (Supplementary Table 13). As almost all glycosylation genes are found in CHO-K1, we expect that the expression and activities of these gene products are more important than their presence in the genome for determining the diversity of glycan structures on protein products in CHO. In RNA-Seq data for exponentially growing CHO-K1 cells, we detected about half of the predicted glycosylation genes (Fig. 3a). N-glycan transferases, mannosyltransferases, sugar-nucleotide synthesis genes and hyaluronoglucosaminidases were enriched for expression or completely expressed. These classes are critical for constructing the core parts of the glycan chains or dictating glycan localization. The significantly depleted classes (P < 0.06) among the expressed fraction of genes included the sulfotransferases, fucosyltransferases and N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) transferases.

(a) While homologs were identified for 99% of the human glycosylation-associated transcripts, only 53% had detectable expression. Glycosylation gene classes enriched in expressed genes (denoted with **) include hyaluronoglucosaminidases, sugar-nucleotide synthesis, mannosyltransferases and lysozomal enzymes. Significantly depleted classes (P < 0.06) in expressed genes (denoted with *) include the sulfotransferases, fucosyltransferases and GalNAc transferases. (b) A selection of CHO N-linked glycosylation pathways are detailed to demonstrate the effects of CHO glycosylation gene expression on the possible glycoforms. (i) A difference between human and CHO glycosylation is seen in the lack of expression of MGAT3, which is responsible for the bisecting β(1,4) GlcNAc that occurs on ∼10% of human antibodies. (ii) The only N-glycan-modifying fucosyltransferase expressed in CHO-K1 is FUT8, which adds fucose to the core glycan by an α(1,6) linkage. (iii) Sialylation of a terminal galactose can occur through α(2,3) or α(2,6) linkages in human. However, CHO ST6Gal genes are not expressed, so CHO glycans primarily have α(2,3) linkages. (iv) The two most abundant sialic acids are Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc. Neu5Gc is immunogenic in humans. Thus, the lack of CMAH expression in the CHO-K1 sample minimizes this response by limiting the conversion of Neu5Ac to Neu5Gc. Pathways are adapted loosely from ref. 55. Abbreviations are defined in Supplementary Table 18.

Bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc)

CHO cell lines often produce glycoforms similar to human glycans. However, CHO cells do not produce the bisecting GlcNAc branch, which is found on about 10% of human IgG glycoforms19. The CHO LEC10 cell line remedies this with a gain-of-function mutation that induces MGAT3 expression, coding for GnTIII/GlcNAcTIII, which adds the bisecting GlcNAc residue20. The fact that the LEC10 cell line gains this functionality suggests that the gene is present in the parent strain. Consistent with this, a homolog to this gene is found in the CHO-K1 genome but is not expressed (Fig. 3b,i).

Fucosylation

Most mammals have five primary types of fucosyltransferases, classified by the linkages between fucose and their substrates: α(1,2), α(1,3), α(1,4), α(1,6) and protein O-fucosyltransferases (Supplementary Table 14 for the glycans fucosylated by each class). However, in the CHO-K1 transcriptome data, only fucosyltransferase 8 (FUT8) and the protein O-fucosyltransferases (POFUT1 and POFUT2) show expression. These add α(1,6)-linked fucose to N-linked glycans (see reaction F6Tg in Fig. 3b,ii) or directly to serine/threonine residues, respectively. Indeed, suppression of FUT8 activity improves the quality of CHO-produced therapeutic antibodies, by removing fucose from the Fc oligosaccharides and altering its binding properties21,22,23. Furthermore, because the α(1,2), α(1,3) and α(1,4)-linked fucosyltransferases are not expressed, the Lewis and ABO blood group glycans will probably not be generated in this CHO-K1 cell-line.

Sialylation

Glycan sialylation can have an impact on the function, longevity and immunogenic effects of proteins. Sialic acids often are the terminal sugar on N-linked glycans. These sugars may increase the lifespan of glycoproteins in the circulatory system by covering the penultimate galactose, which otherwise would bind to the hepatocyte asialoglycoprotein receptor and subsequently be degraded24. The CHO-K1 genome has homologs to all six human ST3Gal enzymes, which form α(2,3) linkages of sialic acid to galactose. Moreover, these genes are expressed as well (Fig. 3b,iii). Although homologs also exist for the human ST6Gal genes, which catalyze α(2,6) linkages of sialic acid to galactose, the transcriptome data show no evidence for ST6Gal gene expression. This is consistent with the observation that CHO cells do not normally show ST6Gal activity19, whereas terminal α(2,3)-linked sialic acid residues are abundant.

Genes involved in immunogenic responses

One challenge in therapeutic protein production is the avoidance of immunogenic responses25,26 that can arise from foreign glycan structures. For example, immunogenic responses can be induced by glycans harboring N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc), the hydroxylated derivative of the sialic acid N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac). This hydroxylation is catalyzed by cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH), which is highly expressed and active in most mammals but not in humans27. Thus, the glycosylated proteins produced in non-human cell lines can induce an immune response in humans unless Neu5Gc production is controlled. Interestingly, although a CMAH homolog is found in the CHO-K1 genome, we did not detect any expression in this analysis (Fig. 3b,iv). This result is consistent with the observation that CHO cell lines contain considerably lower levels of Neu5Gc sialylation in comparison to murine cell lines28.

The antigen Gal-α(1,3)Gal can also elicit immunogenic responses in humans, as most individuals have anti-α-Gal antibodies29. The gene responsible for producing this epitope, glycoprotein α(1,3) galactosyltransferase (Ggta1), is not expressed in human, but is active in mouse. Thus, recombinant IgAs produced in murine cell lines are considerably different from human IgAs. CHO cells lack the sufficient enzymatic machinery to produce glycan structures with the α-Gal epitopes30, except in very small subpopulations31. Furthermore, IgAs produced in CHO cells are similar to human IgA and lack the α-Gal epitope32. Consistent with these findings, a homolog to mouse Ggta1 is present in the CHO-K1 genome but was not expressed (see Supplementary Notes for additional discussion on glycans with potential relevance to immunogenic responses).

Sulfotransferases involved in sulfation of glycosaminoglycans

Despite harboring homologs to human sulfotransferases in the genome, CHO-K1 does not express most of them (Fig. 3a). These enzymes play important roles in the generation of heparan sulfate, which is known to be important for entry of viruses such as HIV33, adenoviruses34 and herpes simplex virus (HSV)35. Interestingly, CHO-K1 has been used extensively to investigate the need for heparan sulfate in viral entry. Although CHO-K1 has heparan sulfate and chondroitin-4-sulfate, several mutants with reduced or no heparan sulfate have been produced by merely inhibiting a few enzymes36.

In the CHO-K1 genome, we identified homologs to most human heparan sulfate glucosamine O-sulfotransferases. Consistent with previous studies37,38,39,40, we found that heparan sulfate glucosamine 2-O-sulfotransferases and heparan sulfate glucosamine 6-O-sulfotransferases are expressed. However, no detectable expression was measured for heparan sulfate glucosamine 3-O-sulfotransferases (HS3ST), which make 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate (important for HSV-1 entry35; Fig. 4). Although CHO-K1 is resistant to HSV-1 infection35, the addition of mouse genes encoding HS3ST to CHO-K1 cells renders them susceptible to HSV-1 infection41. This result suggests that CHO-K1 lacks HS3ST activity, which is consistent with the lack of detectable HS3ST expression in our study.

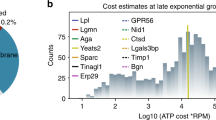

(a) A global view of viral susceptibility genes in CHO-K1 demonstrates no measurable expression for 158 of these genes. The enriched GO cell compartment terms among the nonexpressed susceptibility genes shows that membrane proteins and DNA binding proteins are primarily not expressed. The expression state of all members of the “external side of plasma membrane” GO class is shown (blue and red for expressed and not expressed, respectively). (b) A schematic of entry mechanisms used by HSV-1. Viral entry receptors that are not expressed in CHO are shown by their gene names in red, and missing receptors are shown with a dashed outline. WT, wild type; Mut, mutant; Bov, bovine.

Global analysis of viral susceptibility genes in CHO-K1 genome

Viral infections can contaminate cell culture processes, thus affecting the quality and yield of recombinant protein production. Hence, the property of resistance to viral infection demonstrated by CHO cells further contributes to their preferred choice as hosts for therapeutic protein production42. We next investigated this property using the CHO-K1 genome and transcriptome. Twelve independent studies were summarized to compile a list of human genes important for viral infection43. A total of 388 human genes that were identified in two or more of these independent studies were used for subsequent analysis. Among these, CHO-K1 homologs were not found for four genes (IL1A, SNRPC, MT1X and CD58). Moreover, 158 genes lacked detectable expression levels in the CHO-K1 transcriptome. Among the unexpressed genes, the most enriched GO-terms in the molecular function and biological process classes were glycoprotein binding, T-cell activation and macromolecular assembly (Supplementary Tables 15–17). Many of these genes are either cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), important for viral entry and vesicular trafficking, or plasma membrane proteins involved in viral recognition. Furthermore, several histone proteins involved in nucleosome assembly do not show any detectable expression in the CHO-K1 transcriptome (Fig. 4a).

HSV is a well-studied virus that is unable to infect CHO cells owing to the lack of entry receptors44. The CHO-K1 genome and transcriptome provide insights pertaining to these entry receptors and HSV infection (Fig. 4b). HSV-1 is known to require the Nectin-1/HveC receptor (PVRL1) and herpes virus entry mediator (HveM) for entry into host cells. Although the CHO-K1 genome has homologs to both genes, expression was not detected. Integrins also are cellular receptors that regulate the cell-surface attachment and entry of viruses like HSV. Several integrin genes (e.g., ITGB3, ITGAV and ITGAM) do not show evidence of expression in the transcriptome data. This lack of expression of integrin genes in CHO cells has been documented previously45,46. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) also plays a role in the entry of HSV-1 into CHO-K1 cells. Reports indicate that CHO cells expressing EGFR are susceptible to HSV infection, whereas the wild-type cells lacking EGFR expression are resistant47. Consistent with this observation, an EGFR homolog is in the CHO-K1 genome, but it is not expressed in the CHO-K1 transcriptome.

In addition to HSV, other viruses, such as pseudorabies virus, are blocked from infecting CHO cells at the level of viral penetration48. Receptors for other viruses like HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) are either missing in the CHO-K1 genome or lacking expression in the transcriptome. For instance, the CD4 glycoprotein is not expressed in CHO-K1, thereby blocking entry of HIV-1 into host cells. Similarly, we do not find evidence for the CD58 gene in the CHO-K1 genome. The expression levels of the CAM CD58 correlate with HBV infection severity49. Several other CAMs like CD48 and CD2 are also not expressed in the CHO-K1 transcriptome data. These proteins bind heparan sulfate and play an important role in viral infection50.

The resistance of CHO cells to viral infection is not limited to the regulation of viral entry. For instance, the restriction of Vaccinia virus replication in CHO cells is reported to occur because of the lack of the cowpox host range factor CP77. The absence of CP77 causes a rapid shutdown of viral protein synthesis machinery51. Consistent with this, the CHO-K1 genome does not encode this gene.

Discussion

CHO-derived immortalized cell lines are the preferred host system for therapeutic protein production. CHO cell line engineering work has made incredible progress in optimizing products and titers by focusing on manipulating single genes2 and selecting clones with desirable traits after various treatments (e.g., mutagenesis or media adjustment). This progress has been accomplished without the availability of genomic sequences. Here we present a publicly available annotated genome sequence for a CHO cell line, which represents yet another tool in the bioprocessing toolbox. It is not anticipated that this draft sequence will directly improve product titers to the extent achieved through careful screens in the past. However, the CHO-K1 genomic sequence will facilitate the design of targeted genetic manipulations to aid in cell line engineering (Fig. 5a), help in the elucidation of components underlying poorly characterized phenotypes (Fig. 5b) and allow for more comprehensive deployment of 'omic tools for CHO-K1 and related cell lines (Fig. 5c).

Although significant advances in CHO biology have occurred over the past decades, the accessibility of the CHO-K1 genome will have an impact on at least three major areas. (a) The CHO genome will aid cell line engineering by facilitating the application of experimental and computational sequence-based tools for genetic manipulation and genome analysis. For example, BLAST can be used to identify the CHO sequence of a desired gene, whereas siRNA and site-directed mutagenesis methods can be used to directly modulate gene expression levels and protein activities. Moreover, the genome sequence can be used to reconstruct models of CHO-K1 metabolism, which allow the assessment of how genetic manipulations affect other pathways and can predict nonintuitive genetic changes to improve product yield or quality. (b) The biomolecular mechanisms underlying many phenotypic properties of CHO are poorly characterized (e.g., viral susceptibility). The components underlying these phenotypes can be identified through the comparison of CHO gene content and gene expression with other organisms or cell lines. (c) Although large genomic changes can occur in immortalized and engineered cell lines such as CHO, the CHO-K1 genome can serve as a context for the assembly and analysis of genome sequences from additional CHO cell lines.

A genome-scale analysis of the glycosylation genes in the CHO-K1 genome identifies homologs to 99% of the human glycosylation-associated transcripts, with 53% of them expressed. The high coverage of homologs provides a unique opportunity for glycoform manipulation in CHO cells. Indeed, the high variability of gene silencing has led to the generation of the diverse selection of Lec mutant cell lines20. Moreover, it has been shown that clonal selection can lead to a subpopulation of CHO cells expressing genes like GGTA1, that were thought to be inactive31. This result suggests that many other unexpressed glycosylation genes in the CHO genome can be potentially activated or silenced to alter the repertoire of glycan structures from CHO cells (Fig. 5a). In addition, the genome sequence will facilitate the development of genome-scale metabolic models for CHO cells. Such models allow for the assessment of the network-level effects of cell line treatments, and have been successful at predicting optimal designs for bioprocess optimization in prokaryotes52,53,54.

The genome of CHO-K1 cells can also provide insights into less well-characterized phenotypes. For example, the global analysis of viral susceptibility genes in the CHO genome demonstrates that key plasma membrane receptor genes, CAMs, and genes involved in T-cell activation and macromolecular assembly are not expressed in CHO-K1. Furthermore, the lack of expression of several key viral entry receptors for HSV-1, HIV, HBV and pseudorabies virus opens up the possibility for an in-depth analysis of CHO cell resistance to viral infection. In addition, we found several key regulatory molecules such as histone factors to be lacking expression in CHO-K1. This analysis demonstrates that the genome sequence can be integrated with 'omic data analysis to generate hypotheses to guide further study into poorly characterized phenotypes of CHO cells (Fig. 5b).

The CHO-K1 genome should facilitate the interpretation of various 'omic data types. However, it is important to note that CHO-K1 is an ancestral cell line from which many CHO cell lines have been derived. During the course of the rather stringent manipulations involved in optimizing cell lines (e.g., selection for growth in different media compositions and switching cells from adherent cell culture to suspension-adapted growth), many genomic changes (e.g., SNPs, indels and other structural variations) have likely occurred owing to the inherent genomic instability of these cell lines. Moreover, the cell lines derived from CHO-K1 that are widely used in the industry (e.g., DUKX-B11 and DG44) may contain additional genetic changes from chemical and radiation mutagenesis5,6. Thus, this genome sequence of the ancestral K1 cell line should not be considered as completely representative of all CHO cell lines. However, the full coverage draft genomic sequence of the ancestral K1 cell line will serve as a foundation to support efforts in sequencing other CHO cell lines (Fig. 5c). These additional genomic sequences will provide a context for transcriptomic and proteomic data interpretation in the respective cell lines. It will also facilitate the identification or design of other potential targets or tools for cell line engineering (e.g., microRNAs and short interfering (si)RNAs).

The availability of the CHO-K1 genomic sequence provides a valuable resource for genome-scale CHO-cell research and will aid in manufacturing applications. However, we expect the quality of the genomic sequence will be iteratively improved over time as more genomic information becomes available for CHO-K1 and other CHO cell lines. Moreover, we anticipate that characterizing effects of sequence variations on gene products and expression would improve the functional annotation of these cell lines. These improvements may enhance the application of CHO-cell engineering and other techniques to improve protein production and quality.

Methods

Source of cell line.

The DNA of the CHO-K1 cell line was obtained from ATCC Catalog No. CCL-61.

Sample preparation.

Genomic libraries were prepared following the manufacturer's standard instructions and sequenced on Illumina's HiSeq (2000) platform.

Assembly.

We constructed CHO-K1 genome sequencing libraries with insert sizes of 200 bp, 350 bp, 500 bp, 800 bp, 2 kb, 5 kb, 10 kb and 20 kb to generate a total sequence of 343.64 Gb (Supplementary Table 1). We first assembled the reads with short insert size (<500 bp) using the de Bruijn graph based assembler SOAPdenovo (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/) to obtain long contigs. To construct scaffolds, we realigned all the usable reads onto the contig sequences and obtained 80% of all the aligned paired-end reads. We then calculated the amount of shared paired-end relationships between each pair of contigs, weighted the rate of consistent and conflicting paired-ends, and then constructed the scaffolds step by step, in the increasing order of insert size. However, these scaffolds consisted of internal gaps mainly due to repeats that were masked before the scaffold construction phase. To resolve these gaps, we used the paired-end information to retrieve the read pairs that had one end mapped to the unique contig and the other located in the gap region and then performed a local assembly for these collected reads. See Table 1 for statistics on genome assembly.

Single chromosome amplification.

CHO-K1 cells were grown in F12 medium exponentially. Mitotic cells were collected by the traditional 'shake-off' method. Briefly, culture medium was refreshed right before the collection to remove floating dead cells. Mitotic cells were shaken off from the flask surface by tapping the flask with hands and collected by centrifuging at 150g for 10 min. Cells were swollen with 75 mM KCl for 20 min at 25 °C and chromosomes were isolated with the classical polyamine procedure. The microfluidic chip used in an earlier study9 was modified to remove the cell sorting region and was fabricated by Stanford Microfluidics Foundry. Chromosomes were diluted and loaded onto the microfluidic chip so that around half of the 48 chambers were occupied by single chromosomes. Single chromosome amplification was performed as described in the previous study9. The amplification products from each chamber were retrieved separately. About 20–50 ng of DNA was obtained from each chamber and subjected to Illumina compatible library preparation with the Nextera Kit. An average of 4,384,446 (∼4 million) usable high-quality mapped reads from each preparation were used in the analysis of chromosome assignment (Supplementary Notes and Supplementary Tables 19 and 20).

Karyotyping.

CHO-K1 cells were grown in F12 medium for 5 d after recovery from the stock. 10 μg/ml colchicines were added into 50–75% confluent cells in one 6-cm dish to obtain a final concentration of 0.05 μg/ml colchicine. After culturing for 12 h in an incubator, the cells were then rinsed with PBS and trypsinized for 5 min. Care was taken to ensure that the cells were in a single-cell suspension. The cells were spun through the media for 2 min at 326g, resuspended in 1 ml PBS, spun for 2 min at 326g and then resuspended in 1 ml 0.56% KCl. The cells were incubated at 25 °C for 15 min and spun for 2 min at 326g. After removal of KCl, the cells were gently resuspended in cold 1 ml methanol:acetic acid solution (3:1) and kept on ice for 10 min. The solution was then spun at 734g for 2 min, supernatant was removed and resuspended in 200 μl fresh, cold methanol:acetic acid solution (3:1). After gentle vortexing, 10 μl of suspended cells were added onto a clean slide that is held at a 60° angle in the steam bath to let the methanol evaporate. The cells were then stained with Giemsa stain (Invitrogen/Gibco) for 2 hours. The slide was then rinsed with distilled water and mounted in 50% glycerol/50% PBS. The pictures of the chromosomes were taken using a 50× microscope.

Repeat identification.

We identified known transposable elements using RepeatMasker against the Repbase transposable element library. We also aligned the genome sequence to the curated transposable element–related proteins using RepeatProteinMask to identify highly diverged transposable elements. In addition, we also used RepeatModeller to construct a de novo repeat library for the CHO-K1 cell line11,12,13.

Genome annotation.

We performed de novo gene prediction using Genscan, Augustus and GlimmerHMM with model parameters trained on human and predicted 25,542, 43,042 and 24,021 genes, respectively. We aligned the gene sets from human, mouse and rat (Ensembl release 58) and predicted 33,635, 29,767, and 41,836 genes, respectively. We integrated these predictions into a combined gene set using the GLEAN pipeline to obtain a reconciled gene set containing 19,371 genes. To augment this gene set, we used CHO-K1 transcriptome data to annotate gene structures with the aid of the programs TopHat and Cufflinks. This resulted in a final gene set comprising 24,383 predicted genes and 29,291 transcripts.

Transcriptome sequencing.

We extracted total RNA using the TRIzol Reagent (no. 15596-026), from exponentially growing cells cultured in F-12K Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The samples were treated with DNase in the presence of RNase inhibitor before cDNA synthesis. cDNA was sequenced using the Illumina GA2 technology with the paired-end reads module.

Transcriptome mapping and assembly.

The raw sequence data was filtered by removing reads which had adaptors, or reads that consisted of >10% Ns or reads in which the majority base quality was <5. The filtered reads were mapped to the assembled scaffolds using the alignment tool TopHat, allowing a maximum mismatch of 1 bp to identify the splice junctions. The unmapped reads were used in a seed-and-extend strategy by TopHat to identify reads spanning across the splice junction. This alignment was then assembled into transcripts using the software Cufflinks. Default values were used for all parameters except for the max intron length option (value used 150,000). Transcripts with coverage <1× and length <200 bp were filtered out. The best potential coding region from each of the filtered transcripts was predicted using the software BestORF with parameters trained on mouse ESTs. Finally, the program cuffcompare (part of the Cufflinks suite) was used to compare and reconcile the protein sequences predicted from Cufflinks and BestORF and the Glean annotation.

Identifying homologs of glycosylation and viral susceptibility genes.

A set of 300 glycosylation-associated human transcripts was compiled and curated from the glyco-gene chip array version 4 annotation (Functional Genomics Gateway http://www.functionalglycomics.org/static/consortium/resources/resourcecoree.shtml). We obtained the protein sequences for the human genes of interest from RefSeq Build 37.1 and Ensembl Release 58 and performed a BLAST alignment (blastP) against the protein sequences predicted in the CHO-K1 genome. We used an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5 to obtain the homologs for the genes.

Identification of noncoding RNAs.

The entire fRNAdb was downloaded (http://www.ncrna.org/frnadb/catalog_taxonomy/download) and used as a reference for local blastn with the pooled sample of transcripts. To facilitate cross-species exploration, relaxed parameters were used for both seeding and alignment and an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−2 was implemented. Subsequently, the aligned sequences were annotated by mapping to annotation files from fRNAdb and sorted according to alignment scores.

Accession codes.

Sequence Read Archive: SRA040022.1 for assembly raw data and SRA040045.1 for transcriptome. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession AFTD00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, AFTD01000000.

Accession codes

Accessions

DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL

Sequence Read Archive

References

Walsh, G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2010. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 917–924 (2010).

Lim, Y. et al. Engineering mammalian cells in bioprocessing—current achievements and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 55, 175–189 (2010).

Wurm, F.M. Production of recombinant protein therapeutics in cultivated mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1393–1398 (2004).

Seth, G., Charaniya, S., Wlaschin, K.F. & Hu, W.S. In pursuit of a super producer-alternative paths to high producing recombinant mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18, 557–564 (2007).

Derouazi, M. et al. Stability and cytogenetic characterization of recombinant CHO cell lines established by microinjection and phosphate transfection. in Cell Technology for Cell Products (ed. Smith, R.) 443–446 (Springer Netherlands, 2007).

Pilbrough, W., Munro, T.P. & Gray, P. Intraclonal protein expression heterogeneity in recombinant CHO cells. PLoS ONE 4, e8432 (2009).

Li, R. et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272 (2010).

Miller, J.R., Koren, S. & Sutton, G. Assembly algorithms for next-generation sequencing data. Genomics 95, 315–327 (2010).

Fan, H.C., Wang, J., Potanina, A. & Quake, S.R. Whole-genome molecular haplotyping of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 51–57 (2011).

Deaven, L.L. & Petersen, D.F. The chromosomes of CHO, an aneuploid Chinese hamster cell line: G-band, C-band, and autoradiographic analyses. Chromosoma 41, 129–144 (1973).

Kohany, O., Gentles, A.J., Hankus, L. & Jurka, J. Annotation, submission and screening of repetitive elements in Repbase: RepbaseSubmitter and Censor. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 474 (2006).

Smit, A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-3.0. 1996–2010 〈http://www.repeatmasker.org〉.

Smit, A. & Hubley, R. RepeatModeler Open-1.0. 2008–2010 〈http://www.repeatmasker.org〉.

Gibbs, R.A. et al. Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature 428, 493–521 (2004).

Chinwalla, A.T. et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562 (2002).

Mullins, L.J. & Mullins, J.J. Insights from the rat genome sequence. Genome Biol. 5, 221 (2004).

Elsik, C.G. et al. Creating a honey bee consensus gene set. Genome Biol. 8, R13 (2007).

Walsh, G. & Jefferis, R. Post-translational modifications in the context of therapeutic proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1241–1252 (2006).

Beck, A. et al. Trends in glycosylation, glycoanalysis and glycoengineering of therapeutic antibodies and Fc-fusion proteins. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 9, 482–501 (2008).

Campbell, C. & Stanley, P. A dominant mutation to ricin resistance in Chinese hamster ovary cells induces UDP-GlcNAc:glycopeptide beta-4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III activity. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 13370–13378 (1984).

Kanda, Y. et al. Establishment of a GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (GMD) knockout host cell line: a new strategy for generating completely non-fucosylated recombinant therapeutics. J. Biotechnol. 130, 300–310 (2007).

Natsume, A. et al. Fucose removal from complex-type oligosaccharide enhances the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of single-gene-encoded bispecific antibody comprising of two single-chain antibodies linked to the antibody constant region. J. Biochem. 140, 359–368 (2006).

Satoh, M., Iida, S. & Shitara, K. Non-fucosylated therapeutic antibodies as next-generation therapeutic antibodies. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 6, 1161–1173 (2006).

Morell, A.G., Gregoriadis, G., Scheinberg, I.H., Hickman, J. & Ashwell, G. The role of sialic acid in determining the survival of glycoproteins in the circulation. J. Biol. Chem. 246, 1461–1467 (1971).

Schellekens, H. Immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: clinical implications and future prospects. Clin. Ther. 24, 1720–1740, discussion 1719 (2002).

Sinclair, A.M. & Elliott, S. Glycoengineering: the effect of glycosylation on the properties of therapeutic proteins. J. Pharm. Sci. 94, 1626–1635 (2005).

Chou, H.H. et al. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11751–11756 (1998).

Ghaderi, D., Taylor, R.E., Padler-Karavani, V., Diaz, S. & Varki, A. Implications of the presence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in recombinant therapeutic glycoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 863–867 (2010).

Macher, B.A. & Galili, U. The Galalpha1,3Galbeta1,4GlcNAc-R (alpha-Gal) epitope: a carbohydrate of unique evolution and clinical relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 75–88 (2008).

Jenkins, N., Parekh, R.B. & James, D.C. Getting the glycosylation right: implications for the biotechnology industry. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 975–981 (1996).

Bosques, C.J. et al. Chinese hamster ovary cells can produce galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose antigens on proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 1153–1156 (2010).

Yoo, E.M., Yu, L.J., Wims, L.A., Goldberg, D. & Morrison, S.L. Differences in N-glycan structures found on recombinant IgA1 and IgA2 produced in murine myeloma and CHO cell lines. mAbs 2, 320–334 (2010).

Tyagi, M., Rusnati, M., Presta, M. & Giacca, M. Internalization of HIV-1 tat requires cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3254–3261 (2001).

Dechecchi, M.C. et al. Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are receptors sufficient to mediate the initial binding of adenovirus types 2 and 5. J. Virol. 75, 8772–8780 (2001).

Shukla, D. et al. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99, 13–22 (1999).

Rostand, K.S. & Esko, J.D. Microbial adherence to and invasion through proteoglycans. Infect. Immun. 65, 1–8 (1997).

Kobayashi, M., Habuchi, H., Yoneda, M., Habuchi, O. & Kimata, K. Molecular cloning and expression of Chinese hamster ovary cell heparan-sulfate 2-sulfotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13980–13985 (1997).

Kobayashi, M., Habuchi, H., Habuchi, O., Saito, M. & Kimata, K. Purification and characterization of heparan sulfate 2-sulfotransferase from cultured Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7645–7653 (1996).

Habuchi, H., Habuchi, O. & Kimata, K. Purification and characterization of heparan sulfate 6-sulfotransferase from the culture medium of Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 4172–4179 (1995).

Habuchi, H., Kobayashi, M. & Kimata, K. Molecular characterization and expression of heparan-sulfate 6-sulfotransferase. Complete cDNA cloning in human and partial cloning in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9208–9213 (1998).

Shieh, M.T., WuDunn, D., Montgomery, R.I., Esko, J.D. & Spear, P.G. Cell surface receptors for herpes simplex virus are heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Cell Biol. 116, 1273–1281 (1992).

Wiebe, M.E. et al. A Multifaceted Approach to Assure That Recombinant tPA is Free of Adventitious Virus (Butterworth-Heinemann, London, 1989).

Bushman, F.D. et al. Host cell factors in HIV replication: meta-analysis of genome-wide studies. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000437 (2009).

Conner, J., Rixon, F.J. & Brown, S.M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 strain HSV1716 grown in baby hamster kidney cells has altered tropism for nonpermissive Chinese hamster ovary cells compared to HSV1716 grown in vero cells. J. Virol. 79, 9970–9981 (2005).

Gao, S.-d., Du, J.-z., Zhou, J.-h., Chang, H.-y. & Xie, Q.-g. Integrin activation and viral infection. Virol. Sin. 23, 1–7 (2008).

Gianni, T., Gatta, V. & Campadelli-Fiume, G. {alpha}V{beta}3-integrin routes herpes simplex virus to an entry pathway dependent on cholesterol-rich lipid rafts and dynamin2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22260–22265 (2010).

Nakano, K. et al. Herpes simplex virus targeting to the EGF receptor by a gD-specific soluble bridging molecule. Mol. Ther. 11, 617–626 (2005).

Sawitzky, D., Hampl, H. & Habermehl, K.O. Entry of pseudorabies virus into CHO cells is blocked at the level of penetration. Arch. Virol. 115, 309–316 (1990).

Xie, M. et al. Study on the relationship between level of CD58 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cell and severity of HBV infection. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 118, 2072–2076 (2005).

Ianelli, C.J., DeLellis, R. & Thorley-Lawson, D.A. CD48 binds to heparan sulfate on the surface of epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23367–23375 (1998).

Spehner, D., Gillard, S., Drillien, R. & Kirn, A. A cowpox virus gene required for multiplication in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Virol. 62, 1297–1304 (1988).

Feist, A.M. & Palsson, B.O. The growing scope of applications of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions using Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 659–667 (2008).

Park, J.M., Kim, T.Y. & Lee, S.Y. Constraints-based genome-scale metabolic simulation for systems metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 27, 979–988 (2009).

Yim, H. et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 445–452 (2011).

Hossler, P., Khattak, S.F. & Li, Z.J. Optimal and consistent protein glycosylation in mammalian cell culture. Glycobiology 19, 936–949 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge B. Kingham at the University of Delaware for technical assistance. This work was funded in part by National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC) of China award to a young scientist (30725008), funding from Shenzhen government (ZYC200903240077A), funding for Shenzhen Key labs (CXB200903110066A), Guangdong Innovation Team Funding, National Basic Research Program of China (973 program, 2007CB815703), US National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2P20RR016472-10 and National Cancer Institute Small Business Innovation Research grant (NIH R44CA139977). M.R.A. acknowledges funding from the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation grant 07-015498.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.O.P., J.W., I.F., X.X. and Z.C. conceived and designed the study. Z.C., Y.G., S.H. and K.H.L. performed sample preparation and sequencing. X.X., S.P. and W.C. performed the genome assembly. X.X., S.P., X.L., M.X., W.W., H.N. and N.E.L. performed genome annotation and evolutionary analysis. H.C.F., J.W., B.P., W.K., N.N. and S.R.Q. generated data and performed the microfluidic chromosomal analysis. The method and data for chromosome analysis was conceived and generated at Stanford. H.N., N.E.L., M.J.B., W.K. and M.R.A. performed the genomic and transcriptomic analysis of the glycosylation and viral susceptibility genes. H.N., N.E.L. and B.O.P. wrote the paper and coordinated research efforts between authors. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–6 and Supplementary Notes (PDF 1648 kb)

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Tables 1–20 (XLS 770 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This licence does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar license.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Nagarajan, H., Lewis, N. et al. The genomic sequence of the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cell line. Nat Biotechnol 29, 735–741 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1932

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1932

This article is cited by

-

Microevolutionary dynamics of eccDNA in Chinese hamster ovary cells grown in fed-batch cultures under control and lactate-stressed conditions

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Simplifying glycan monitoring of complex antigens such as the SARS-CoV-2 spike to accelerate vaccine development

Communications Chemistry (2023)

-

Targeting DNA repair pathways with B02 and Nocodazole small molecules to improve CRIS-PITCh mediated cassette integration in CHO-K1 cells

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Sialic acid O-acetylation patterns and glycosidic linkage type determination by ion mobility-mass spectrometry

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Glutamine synthetase (GS) knockout (KO) using CRISPR/Cpf1 diversely enhances selection efficiency of CHO cells expressing therapeutic antibodies

Scientific Reports (2023)