Abstract

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is an important contributor to air pollution and can adversely affect human health1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. A decrease in NO2 concentrations has been reported as a result of lockdown measures to reduce the spread of COVID-1910,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Questions remain, however, regarding the relationship of satellite-derived atmospheric column NO2 data with health-relevant ambient ground-level concentrations, and the representativeness of limited ground-based monitoring data for global assessment. Here we derive spatially resolved, global ground-level NO2 concentrations from NO2 column densities observed by the TROPOMI satellite instrument at sufficiently fine resolution (approximately one kilometre) to allow assessment of individual cities during COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020 compared to 2019. We apply these estimates to quantify NO2 changes in more than 200 cities, including 65 cities without available ground monitoring, largely in lower-income regions. Mean country-level population-weighted NO2 concentrations are 29% ± 3% lower in countries with strict lockdown conditions than in those without. Relative to long-term trends, NO2 decreases during COVID-19 lockdowns exceed recent Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI)-derived year-to-year decreases from emission controls, comparable to 15 ± 4 years of reductions globally. Our case studies indicate that the sensitivity of NO2 to lockdowns varies by country and emissions sector, demonstrating the critical need for spatially resolved observational information provided by these satellite-derived surface concentration estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is an important contributor to air pollution as a primary pollutant and as a precursor to ozone and fine particulate matter production. Human exposure to elevated NO2 concentrations is associated with a range of adverse outcomes such as respiratory infections2,3,4, increases in asthma incidence5,6, lung cancer7 and overall mortality8,9. NO2 observations indicate air quality relationships with combustion sources of pollution such as transportation6,21. Initial investigations found substantial decreases in the atmospheric NO2 column from satellite observations10,11,12,13,14,15,16 and in ambient NO2 concentrations from ground-based monitoring17,18,19,20 during lockdowns enacted to reduce the spread of COVID-19. However, questions remain about the relationship of atmospheric columns with health- and policy-relevant ambient ground-level concentrations, and about the representativeness of sparse ground-based monitoring for broad assessment. Thus, there is need to relate satellite observations of NO2 columns to ground-level concentrations. It is also important to consider the effect of meteorology on recent NO2 changes22 and to quantify NO2 changes due to COVID-19 interventions in the context of longer-term trends23. Furthermore, air quality monitoring sites tend to be preferentially located in higher-income regions, raising questions about how NO2 changed in lower-income regions where larger numbers of potentially susceptible people reside. Estimates of changes in ground-level NO2 concentrations derived from satellite remote sensing would fill gaps between ground-based monitors, offer valuable information in regions with sparse monitoring, and more clearly connect satellite observations with ground-level ambient air quality.

Previous satellite-derived estimates of ground-level NO2 used information on the vertical distribution of NO2 from a chemical transport model to relate satellite NO2 column densities to ground-level concentrations24,25,26. Recent work improved upon this technique by allowing the satellite column densities to constrain the vertical profile shape, allowing for more accurate representation of sub-model-grid variability, reducing the sensitivity to model resolution and simulated profile shape errors, and improving agreement between the satellite-derived ground-level concentrations and in situ monitoring data27. Applying this technique to examine changes in NO2 during lockdowns bridges the gap between previous studies focusing on either ground monitors or satellite column densities, thus providing a more complete and reliable picture of the changes in exposure.

Since 2005, the gold standard for satellite NO2 observations has been the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on board NASA’s Earth Observing System Aura satellite28,29. The newest remote sensing spectrometer, the European Space Agency’s TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI)30 on the Copernicus Sentinel 5p satellite, has been providing NO2 observations with finer spatial resolution and higher instrument sensitivity since 2018. These attributes allow the generation of TROPOMI NO2 maps at 100 times finer resolution (approximately 1 × 1 km2) with a one-month averaging period31,32, an improvement over the spatial and temporal averaging needed for accurate OMI maps (typically approximately 10 × 10 km2 over one year)24. Concurrently, the excellent stability of the OMI instrument over the last 15 years provides an ideal dataset for long-term trend analysis28,33 that offers context for recent TROPOMI data.

Lockdown restrictions act as an experiment about the efficacy of activity reductions on mitigating air pollution. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT, https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker#data) has been monitoring government-imposed restrictions, and studies have indicated that NO2 decreases were larger for cities in countries with strict lockdowns34. However, there is limited information on lockdown stringency on sub-national levels or on how various emission sectors respond to lockdowns. An observation-based metric for lockdown intensity could provide useful information for examining lockdowns on city-level scales or for examining the effects on air quality that are associated with lockdowns in different emission sectors.

Here we leverage the high spatial resolution of TROPOMI to infer global ground-level NO2 estimates at, to our knowledge, an unprecedented spatial resolution sufficient to assess individual cities worldwide, and to examine changes in ground-level NO2 occurring during COVID-19 lockdowns from January–June 2020. Case studies presented here demonstrate how the satellite-based estimates provide information on important spatial variability in lockdown-driven NO2 changes, and in the NO2 response to lockdowns in various emissions sectors. We also use TROPOMI to provide fine-scale structure to the long-term record of OMI observations (2005–2019), which provides an opportunity to examine trends in ground-level NO2 over the last 15 years to provide context for the recent changes.

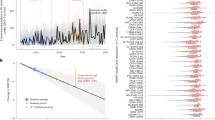

Global NO2 concentrations and trends

Global annual mean TROPOMI-derived ground-level NO2 concentrations for 2019 provide an initial baseline (Fig. 1). The excellent resolution (~1 × 1 km2) of ground-level NO2 concentrations reveal pronounced heterogeneity (Supplementary Figs. 1–7). NO2 enhancements are apparent over urban and industrial regions. TROPOMI-derived ground-level concentrations exhibit consistency with in situ observations (r = 0.71, N = 3,977, in situ versus satellite slope = 0.97 ± 0.02), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Neglecting the spatial and temporal variability in the NO2 column-to-surface relationship degrades the consistency with ground monitors (slope = 0.78 ± 0.01), demonstrating the importance of relating satellite columns to surface concentrations for exposure assessment.

a, TROPOMI-derived 2019 annual mean ground-level NO2 concentrations at approximately 1 × 1 km2 resolution. b, Trend in OMI and TROPOMI-derived annual mean ground-level concentrations from 2005–2019. The colour intensity represents the statistical significance of the trend. c–e, Population-weighted mean NO2 from ground monitors and from satellite-derived NO2 sampled at ground-monitor locations in China (c), Europe (d) and North America (e), normalized by the mean concentration during the period where ground-monitor data are available. The black (ground-derived) and red (satellite-derived) values give the trends for the period where ground-monitor data are available. Only monitors with data available over the entire time period are included. Error bars represent population-weighted standard deviations. f, Population-weighted mean satellite-inferred ground-level NO2 concentrations in South America, Africa and the Middle East, and Oceania. Trends during the given time periods are given at top. Time periods were chosen to reflect the most recent years where a consistent trend is observed. Error bars represent uncertainties in population-weighted means using a bootstrapping method.

Examination of long-term changes in air pollution offers context for changes during COVID-19 lockdowns (Fig 1, Supplementary Figs. 1–7). Satellite-derived NO2 concentrations decreased from 2005–2019 in urban areas across most of the USA and Europe, eastern China, Japan, and near Johannesburg, South Africa, largely reflecting emission controls on vehicles and power generation. NO2 increases are observed in Mexico, the Alberta oil sands region in northern Canada, and throughout the Balkan peninsula, central and northern China, India and the Middle East, broadly consistent with reported trends in ground-monitor data35,36,37. Trends in China can be separated into three regimes: ground-level concentrations increased in China from 2005–2010, plateaued from 2010–2013, and decreased from 2013–2019. This change was driven by stricter vehicle and power generation emission standards38 and is consistent with observed changes in NO2 columns39,40. Similarly, concentrations increased in urban and industrial areas of South America from 2005–2010, and in South Africa and the Middle East from 2005–2015, and decreased in more recent years. Maps of trends in these regions for these time periods are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Concentrations in India increased across both time periods owing to increasing coal-powered electricity demands and growing industrial emissions41. Trends in population-weighted NO2 concentrations, used to represent population NO2 exposure, were calculated using ground monitors and coincidently sampled satellite observations in North America, Europe and China. Satellite-derived concentrations exhibit decreasing trends (−2.8 ± 0.2% yr−1 in Europe 2005–2019, −4.3 ± 0.7% yr−1 in North America 2005–2019, and −6.0 ± 0.7% yr−1 in China 2015–2019) that agree well with trends in the ground-monitor data (within 0.7% yr−1 in North America, 0.3% yr−1 in Europe, and 1.2% yr−1 in China).

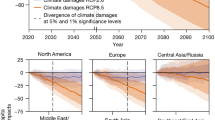

Regional NO2 changes during lockdowns

Figure 2 shows the April 2020 to April 2019 difference between mean ground-level NO2 concentrations derived from TROPOMI observations. NO2 concentrations are lower in most regions in 2020 than in 2019, particularly over urban areas, with global population-weighted mean concentrations decreasing by 16% in 2020 relative to 2019. Fig. 3 shows regional maps focusing on the month with the largest change in population-weighted regional mean concentration for each region, with an additional period included for China, as lockdown restrictions occurred earlier than in other countries. Regional population-weighted mean concentrations decreased by 17–43%. The largest decreases occur in China in February with concentration decreases exceeding 10 parts per billion by volume (ppbv) and substantial decreases persisting in eastern urban areas through April. Thus these lockdown measures temporarily bolstered the decreasing trends across North America42 and Europe25 over the last two decades and in China since 201243, owing to technological advances in vehicles and power generation, while temporarily buffering changes from increasing energy demands in India and the Middle East40,44,45. NO2 increases in April 2020 in central China (Chengdu and Chongqing) because lockdowns began lifting during this time.

Left in each pair of images, TROPOMI-derived monthly mean NO2 differences from 2020–2019 at approximately 1 × 1 km2. Right, OMI+TROPOMI-derived NO2 trends. Annual mean long-term trends are corrected for seasonal variation. The time periods for trend calculations in each region were chosen to reflect the most recent years where a consistent trend is observed and are indicated above the maps. Value under each panel represents population-weighted mean difference for the given region.

Figure 3 shows maps of long-term NO2 trends for context. In most regions, the observed changes during COVID-19 restrictions exceed the expected year-to-year differences observed in the long-term trends (Table 1). 2020–2019 population-weighted mean concentration changes are lower than long-term trends by factors of 17 ± 7 in North America, 19 ± 2 Europe, of 2.9 ± 0.6 in Africa and the Middle East, of 3.6 ± 0.6 in Asia, 8 ± 7 in South America, and 2 ± 2 in Oceania.

Meteorological differences are calculated with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model using emission inventories that do not include changes that occurred owing to COVID-19 lockdown policies but do reflect meteorological changes. Supplementary Fig. 10 shows TROPOMI-derived changes at 2.0° × 2.5° resolution for comparisons with simulated values at the same resolution. Population-weighted NO2 concentration changes due to meteorology in Asia, Europe, South America, Africa and the Middle East are a factor of 2–6 smaller than observed; thus, meteorology alone cannot explain the observed decreases. Concentration increases in the central USA, as noted in other studies10, do not appear to be meteorologically driven and may be due to changes in biogenic NOx sources.

Supplementary Fig. 11 shows the ratio of population-weighted January–June monthly mean NO2 concentrations in 2020 to 2019 across selected regions. Most regions have the largest decrease in NO2 in April when lockdown conditions were strongest (the global mean COVID restriction stringency index (defined in Methods) reached a maximum of 0.79 on 18 April), apart from China, where lockdowns were initiated in January. In most regions, 2020 NO2 concentrations return towards pre-lockdown values in May or June owing to relaxing travel restrictions (30 June global mean stringency index, 0.60) as well as increasing soil, lightning and biomass-burning emissions that lessen the sensitivity of ambient NO2 to anthropogenic emissions.

City- and country-level NO2 changes

The fine resolution of our satellite-derived ground-level NO2 dataset enables the assessment of larger changes in NO2 concentrations from 2020–2019 evident at the city level. We calculate changes in TROPOMI-observed monthly mean ground-level NO2 from 2020–2019 over 215 major cities (the ten most populous cities in each country with a population greater than 1 million) for the month with the greatest monthly mean lockdown stringency index, compared with expected changes due to meteorology and long-term trends (Supplementary Table 1). Most cities have TROPOMI-derived NO2 decreases that cannot be explained by changes due to meteorology alone. For example, satellite-derived NO2 concentrations in Beijing decreased by 45% in March, despite meteorological conditions favourable to increased NO2. Jakarta, Manila, Istanbul, Los Angeles and Buenos Aires among others had decreased NO2, despite similarly unfavourable meteorological conditions. Some cities, including Moscow, Tokyo, London, New York, Toronto and Delhi, had meteorological conditions that would have led to NO2 decreases regardless of emission changes, but observed concentration changes exceeded the expected meteorological change.

Consistent analysis of individual cities as enabled by this dataset reveals a mean observed decrease of 32 ± 2% for these 215 cities. The mean expected meteorologically driven change was −1 ± 1% and the mean expected change owing to long-term trends was a decrease of 1.4 ± 0.4%. Supplementary Fig. 12 shows these reductions to be consistent with those found in 381 ground-monitor values from 79 studies34 (32 ± 2%). Of the 215 cities included here, 65 are in countries that did not have ground-monitoring data available for previous studies. Notably, the 65 cities without monitors are largely in lower-income countries of Africa and southeast Asia. The average gross national income per capita for unmonitored countries is US$7,100, compared to US$25,000 for monitored countries, illustrating the potential of satellite-derived ground-level concentrations for providing information about lower-income regions. In summary, the observed decreases in NO2 across more than 200 cities worldwide were generally driven by COVID-19 lockdowns, with locally varying modulation by meteorology and business-as-usual changes.

Table 1 shows monthly mean country-level population-weighted NO2 concentrations, changes during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, meteorological effects and long-term trends for the month with the greatest 2020–2019 change. Meteorological effects were generally minor at the national and regional scale. Multi-year trends provide context for the scale of the changes observed during COVID-19 lockdowns. The decrease in March NO2 concentrations in the USA from 2019 to 2020 was equivalent to four years of long-term NO2 reductions. Similarly, changes in NO2 during COVID-19 lockdowns were equivalent to greater than three years of reductions in China, and up to 23 years in Germany. Globally, the April 2020 population-weighted NO2 concentration was 0.53 ± 0.06 ppbv lower than in April 2019, equivalent to 15 ± 4 years of global NO2 reductions.

NO2 as a lockdown indicator

The relationship between this satellite-derived ground-level NO2 dataset and lockdown stringency provides supporting evidence for the impact of travel restrictions (Supplementary Fig. 13). The ratio of population-weighted mean observed NO2 in 2020 to 2019 was calculated for each country and each month from January to June. The 2020/2019 NO2 ratio in countries with the strictest lockdown (monthly minimum stringency indices greater than the 75th percentile) was 29 ± 3% lower than for countries with the weakest lockdowns (monthly median stringency indices less than the 25th percentile). Maximum and median ratios were also lower for countries with strict lockdowns. Both distributions have similar variability (standard deviations 0.02 and 0.03) which demonstrates similar interannual variability due to meteorology for both sets. When focusing on only the month with the strictest lockdown for each country, changes in population-weighted NO2 are correlated with lockdown intensity, with changes in countries with strict lockdowns (average decrease 43% if lockdown index >80) more than three times as large as in those with weaker lockdowns (12% if lockdown index <40).

This relationship suggests that changes in satellite-derived NO2 concentrations offer observational information on the spatial distribution of lockdown effects that is not available through policy-based stringency indices. For example, although the policy-based stringency index in most cases provides a single value for a country, city-level NO2 concentration decreases in India are in the range 30–84%, reflecting variability in local mobility restrictions, emissions sources, and their sensitivity to lockdowns. Supplementary Fig. 14 explores the sensitivity of NO2 concentrations to emissions from the transportation and electricity sectors in India, China and the USA by examining the distribution of changes in NO2 concentration at the 20 largest population centres and 20 largest fossil fuel-burning power plants in each country. All countries have substantial NO2 decreases in cities, but the sensitivities vary in areas associated with the electricity sector, with decreasing concentrations near power plants in India (mean change −35 ± 4%) and China (−28 ± 8%) but insignificant changes in the USA (−4 ± 8%). Observed NO2 changes at these power plants exceed expected changes from meteorology alone (−8 ± 2%, −1 ± 4% and −1 ± 3% in India, China and the USA, respectively). Although variability between power plants reflects a mix of regionally varying factors, including meteorology, electricity demand, fuel type and plant-specific emission controls, as well as changes in nearby emissions from other sectors including transportation, these differences indicate a sensitivity of local air quality to activity restrictions affecting the energy sector.

Examining geographic differences in satellite-derived NO2 concentrations within metropolitan regions is also informative. For example, variability between emission sources is apparent around the city of Atlanta, Georgia, USA (Supplementary Fig. 15). The population-weighted NO2 concentration in Atlanta and the surrounding region dropped by 28% from April 2019 to 2020, but with substantial spatial variability in the observed change. The greatest NO2 decreases are found near a large coal-powered electricity plant to the southeast of the city, with significant changes near another plant to the northwest. Decreases were also larger near the Hartsfield–Jackson International Airport—reflecting the dramatic slowdown in air travel—and over suburban regions to the west and northeast of the city centre, than in the downtown core. Supplementary Fig. 15 also demonstrates the range of NO2 changes experienced by the local population. Over 1.2 million people live in regions where NO2 decreases exceeded 40%, whereas nearly 1 million people experienced decreases of 10% or less. Similar heterogeneity in population exposure exists in other major cities, as demonstrated by Supplementary Fig. 16. For example, a subset of over 1 million people in the Paris metropolitan area experienced NO2 decreases of 75% (4.5 ppbv) or more (10th-percentile exposure), whereas another similar-sized subset experienced changes of 23% (0.6 ppbv) or less (90th-percentile exposure). Of the cities examined here, 68 had an interquartile range in population exposure change during lockdowns of 20 percentage points or larger, 22 of which were unmonitored cities. Studies have found that NO2 changes during lockdowns varied among socioeconomic, ethnic and racial groups in US cities46, and thus the variability in other major cities observed here suggest similar disparities may occur elsewhere. The heterogeneity of NO2 changes demonstrates the need for the finely resolved information on lockdown effects that is offered by satellite observations.

We find that using this satellite-derived NO2 dataset as an observational proxy for lockdown conditions is also useful for identifying links between lockdown-driven emission changes and secondary pollutants. For example, several studies have found little to no change in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) during lockdowns as meteorology, long-range transport and nonlinear chemistry complicate the relationship between PM2.5 and NOx emissions47,48. A challenge in these studies has been limited observational information on the local lockdown intensity. Recent work examining 2020–2019 changes in satellite-derived PM2.5 concentrations found that lockdown-driven decreases in PM2.5 concentration can be identified by separating the meteorological effects from emissions effects using chemical transport modelling and focusing on regions with the greatest sensitivity to emission reductions49. Here we examine that same satellite-derived PM2.5 dataset using TROPOMI-derived ground-level NO2 concentrations to identify the regions where PM2.5 concentrations are most likely associated with lockdowns or sensitive to NOx emissions. Supplementary Fig. 17 shows the distribution of changes in monthly mean PM2.5 concentrations from 2020–2019 for China in February and North America and Europe in April. Regions with the largest 2020–2019 NO2 concentration decreases (90th percentile) are considered to be those with significant NOx emission reductions. Population-weighted mean PM2.5 concentrations decreased overall; however, regions with the largest NO2 decreases experienced greater local changes in PM2.5 concentration in China and to a lesser extent in North America, indicating that the sensitivity of PM2.5 to changing NOx emissions can be inferred. The year-to-year variability of PM2.5 concentrations in Europe is similar regardless of changes in NO2, indicating a greater role of meteorology or transport on PM2.5 in this region and period. These results are consistent with previous findings when using chemical transport modelling to identify regions where local emissions are important49. Thus, the observational proxy on lockdown conditions offered by these satellite-derived surface NO2 concentrations offers spatially resolved information to identify where PM2.5 and NO2 (and by proxy, NOx emissions) are most strongly coupled.

Implications

The pronounced decreases in ground-level NO2 found here for over 200 cities worldwide during COVID-19 lockdowns are a culmination of recent advancements in techniques for estimating ground-level NO2 from satellite observations27 alongside higher-resolution satellite observations from TROPOMI that allow for estimating high spatial resolution, short-term changes in NO2 exposure. This method bridges the gap between monitor data (that measure ground-level air quality but have poor spatial representativeness) and satellite column data (that provide spatial distributions but are less representative of ground-level air quality). The ability to infer global ground-level NO2 concentrations with sufficient resolution to assess individual cities and even within-city gradients is an important development in satellite remote-sensing instrumentation and algorithms. Additionally, these satellite-derived ground-level NO2 concentrations offer information about unmonitored communities and populations that are underrepresented in studies focused on ground-monitor data. These cities are found to have different characteristics of NO2 concentrations and changes during lockdowns that motivate the need for satellite observations in the absence of local ground monitoring. The changes in ground-level NO2 due to COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, which exceed recent long-term trends and expected meteorologically driven changes, demonstrate the impact that policies that limit emissions can have on NO2 exposure. This information has relevance to health impact assessment; for example, studies focused on ground-monitor data have indicated improvements in health outcomes related to improved air quality during lockdowns, including an estimated 780,000 fewer deaths and 1.6 million fewer paediatric asthma cases worldwide due to decreased NO2 exposure20. Our study demonstrates considerable spatial variability in lockdown-driven ground level NO2 changes that does not necessarily correlate with population density, demonstrating probable uncertainties arising from extrapolating changes observed by ground monitors to estimate broad changes in population NO2 exposure. Satellite-based ground-level NO2 estimates provide high-resolution information on the spatial distribution of NO2 changes in 2020 that cannot be achieved through ground monitoring, particularly in regions without adequate ground monitoring, and should improve exposure estimates in future health studies. Additionally, ground-level concentrations from downscaled OMI observations provide the opportunity to contrast effects of past mitigation efforts on long-term NO2 trends against the short-term changes resulting from more dramatic regulations, and a chance to improve studies of health outcomes related to long-term NO2 exposure.

The strength of the links between observed changes in NO2 concentration and lockdown stringency indicates that satellite-based ground-level NO2 concentrations offer useful observational, spatially resolved information about lockdown conditions. This provides an observational metric for examining the efficacy of lockdown restrictions on restricting mobility for studies examining the spread of COVID-19. Here we exploited this information to illustrate the differing sensitivity of NO2 concentrations to changes in various emission sources to lockdown restrictions. Future applications of these data could include examining socioeconomic drivers that impact this variability within and between countries. Comparisons between satellite-derived ground-level NO2 and PM2.5 also indicate the utility of these data as an observational proxy for identifying regions where secondary pollutants such as PM2.5 or ozone are more likely to be sensitive to NOx emissions; these links are otherwise difficult to trace without the use of chemical transport models50.

These data offer information to improve NO2-exposure estimates, to examine exposure trends, and subsequently estimate changes in health burden. These developments provide an excellent opportunity for advances in air quality health assessment in relation to NO2 and its combustion-related air pollutant mixture.

Methods

Data

We use tropospheric NO2 columns from the OMI (NASA Standard Product version 4)51 and TROPOMI52,53 satellite instruments. Both instruments measure solar backscatter radiation in the ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectral bands on sun-synchronous orbits with local overpass times around 1:30 p.m. TROPOMI observations from April 2018–October 2020 are used to examine near-term NO2, and OMI observations from January 2005–December 2019 are used to examine long-term trends. Observations with retrieved cloud fractions greater than 0.1 or flagged as poor quality or snow-covered (that is, TROPOMI quality assurance flag <0.75) are excluded. Although the resolution of TROPOMI observations is 3.5 × 5.5 km2, several studies have demonstrated that oversampling techniques can provide accurate NO2 maps at 1 × 1 km2 resolution when averaging over a one-month period31,32,54. An area-weighted oversampling technique55,56 is used to map daily satellite NO2 column observations from TROPOMI onto a ~0.01° × 0.01° (~1 × 1 km2) resolution grid and from OMI to a 0.1° × 0.125° (~10 × 10 km2) grid, as these resolutions balance the need of fine resolution for observing fine-scale structure and of minimizing the effects of sampling biases and noise in the observations. Supplementary Fig. 8 provides further evidence that a one-month period provides sufficient observations for a 1 × 1 km2 map as the agreement between TROPOMI-derived surface concentrations and in situ observations does not deteriorate when the sampling period is reduced from one year to one month. Additionally, we compared 2019 monthly mean concentration estimates with the 2019 annual mean and find high correlation (r = 0.90), indicating similar spatial variability. We correct for sampling biases in the satellite records due to persistent cloudy periods or surface snow cover using a correction factor calculated with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model described below by sampling the GEOS-Chem-simulated monthly or annual mean column densities to match the satellite.

We use hourly ground-level NO2 measurements from monitors to constrain and evaluate the satellite-based estimates. Observations from the US Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System (https://aqs.epa.gov/aqsweb/documents/data_mart_welcome.html) over the continental USA from 2005–2020, Environment and Climate Change Canada’s National Air Pollution Surveillance Program (http://maps-cartes.ec.gc.ca/rnspa-naps/data.aspx) from 2005–2019, European Environment Agency (https://aqportal.discomap.eea.europa.eu/index.php/users-corner/) from 2005–2020, National Air Quality Monitoring Network in China from 2015–2020 were (obtained from https://quotsoft.net/air) were used. European monitors classified as near-road are excluded. Monthly and annual mean concentrations at each site are calculated by averaging hourly observations between 13:00–15:00 h (corresponding to satellite overpass times) and corrected for the known overestimate in regulatory measurements due to interference of other reactive nitrogen species following Lamsal et al.24.

To examine the relationship between COVID-19 lockdown policies and ground-level NO2 concentrations, we use the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT, https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker#data). OxCGRT provides a daily country-level policy ‘stringency index’ ranging from 0–100 that is based on containment and closure policies (for example, school and workplace closures, stay-at-home orders, gathering restrictions). We also use population density data from the Center for International Earth Science Information Network for the available years of 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020, and linearly interpolate for other years (https://doi.org/10.7927/H4JW8BX5).

Inferring ground-level concentrations from satellite column observations

Ground-level NO2 concentrations are derived from TROPOMI NO2 columns following the method developed in Cooper et al.27. This algorithm builds upon the method first developed by Lamsal et al.24 which uses the GEOS-Chem-simulated relationship between ground-level and tropospheric column NO2 concentrations. The updated algorithm uses the satellite-observed column densities and ground-monitor data as observational constraints on the shape of the boundary layer profile, reducing the sensitivity to model resolution and improving agreement between satellite-derived ground-level concentrations and in situ observations. Technical details on the application of this method as used here are available in the Supplementary Information.

For long-term trend analysis, we use more recent TROPOMI observations to provide fine-resolution spatial structure to the OMI-observed NO2 columns following the method of Geddes et al.25. Annual mean OMI NO2 columns are gridded to 10 × 10 km2 resolution and a median-value filter is applied to reduce noise. We smooth the two-year (April 2018–April 2020) mean TROPOMI NO2 columns mapped at 1 × 1 km2 resolution using a two-dimensional boxcar algorithm with an averaging window of 10 × 10 km2 to match the resolution of the gridded OMI NO2 columns. We then downscale the annual mean OMI NO2 columns using the ratio of the 1 × 1 km2 TROPOMI columns to the smoothed TROPOMI columns. The downscaled columns are then used to infer ground-level concentrations following the method used for TROPOMI. Supplementary Fig. 18 demonstrates the utility of this downscaling approach by comparing OMI-derived ground-level concentrations to those derived from the downscaled columns. When comparing 2020–2019 changes in monthly mean concentrations to long-term trends, trends in annual mean concentration are scaled by the ratio of the 2019 monthly mean to the 2019 annual mean to account for seasonality.

The GEOS-Chem chemical transport model version 11-01 is used here (https://geos-chem.seas.harvard.edu/) for NO2 vertical profiles and to assess meteorological effects. GEOS-Chem simulates atmospheric chemistry and physics using a detailed HOx–NOx–VOC–O3–aerosol chemical mechanism57,58 driven by meteorological data from the MERRA-2 Reanalysis of the NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office59. A detailed description of the simulation is provided in Hammer et al.60. We replace the a priori profile used in the retrieval with profiles simulated using the GEOS-Chem model to ensure consistency in vertical profile representation between TROPOMI, OMI, and GEOS-Chem. We simulate NO2 profiles from January 2005–June 2020 at a horizontal resolution of 2° × 2.5°. Supplementary Fig. 19 shows results from tests using a simulation at 0.5° × 0.625° which was available over North America, Europe and Asia. Satellite-derived ground-level concentrations at ~1 × 1 km2 resolution were not sensitive to the resolution of the a priori information, consistent with Cooper et al.27, and thus the 2° × 2.5° was used here for consistency across all regions.

Inferring country- and city-level NO2 changes during COVID lockdowns

City-level monthly means are calculated from TROPOMI-derived concentrations at ~1 × 1 km2 resolution averaged over a 20 × 20 km2 region surrounding the city. Meteorological effects are estimated using GEOS-Chem simulations at 2° × 2.5° resolution with consistent emissions in both years, downscaled to ~1 × 1 km2 resolution using the horizontal variability of TROPOMI-derived ground-level concentrations. Supplementary Fig. 20 demonstrates that GEOS-Chem simulations can represent meteorologically driven changes in NO2 in pre-lockdown periods. Trends are defined over 2005–2019 for North America, Europe and Australia, 2015–2019 for Asia and Africa, and 2010–2019 for South America and scaled for seasonality.

Country-level population-weighted means, used to represent population NO2 exposure, are calculated using concentrations at ~1 × 1-km2 resolution via:

where xi is the NO2 concentration and Pi is the population within a ~1 × 1-km2 grid box.

Limitations and sources of uncertainty

Uncertainty values for country- and region-level population-weighed means (σtotal) represent the sum in quadrature of three main error sources:

Uncertainty in population-weighted means (σpop-weighted) are estimated using a bootstrapping method61. Uncertainty in 2020 NO2 estimates (σAMF2020) arises from the use of simulated profiles as a priori information for calculating satellite air mass factors and for informing the column-to-ground-level relationship, as these simulations use emission inventories that do not reflect changes resulting from COVID-19-related travel restrictions. Such errors may result in overestimating the fraction of columnar NO2 near the surface, resulting in an overestimate in satellite-derived ground-level NO2 concentrations and an underestimate of the 2020–2019 difference. We estimate σAMF2020 by performing sensitivity studies where anthropogenic NOx emissions were uniformly reduced by 50% to assess the effect of such emission errors on ground-level NO2 estimates. Reducing anthropogenic NOx emissions by 50% led to a 5% change in monthly mean population weighted NO2 concentrations in North America, Europe and Asia for March 2020. Aerosols can also contribute to uncertainty in air mass factor calculations, as a reduction in anthropogenic scattering aerosols during lockdowns may reduce air mass factors leading an underestimation of the NO2 change62,63. However, this is likely to be a minor source of uncertainty in estimated NO2 changes due to lockdown, because aerosol concentration changes were small in most regions49 and a reduction in aerosol concentration of 10% translates to an uncertainty in NO2 of less than 5%64. Additional uncertainty (\({\sigma }_{{{\Omega }}_{\max }}\)) may arise from the choice of the Ωmax parameter (described in the Supplementary Information), particularly in regions where there are insufficient ground-monitor data for constraining Ωmax. We estimate \({\sigma }_{{{\Omega }}_{\max }}\) by evaluating the sensitivity of mean population-weighted NO2 concentrations to a 20% change in Ωmax. Median country-level \({\sigma }_{{{\Omega }}_{\max }}\) values are ~7%. Uncertainty values in trends are calculated by a weighted linear regression where annual mean concentrations are weighted by σtotal.

Although tests here indicate that satellite-derived ground-level NO2 concentrations are insensitive to the resolution of the simulated data used in the algorithm, discontinuities can occur at the edges of simulation grid boxes. To quantify this uncertainty, we calculate the difference across the grid box boundaries in each region. In most regions the discontinuity is small (<0.5 ppbv in 92% of total cases, and in 98% of cases where NO2 concentrations >2 ppbv) although can be larger in some cases (>2 ppbv in 0.02% of cases where NO2 concentrations >2 ppbv, maximum of 4.5 ppbv).

The along-track resolution of TROPOMI observations changed from 7 km to 5.5 km in August 2019. This change may influence interannual comparisons, particularly with respect to the sub-grid downscaling of process which relies on the spatial structure observed by the satellite. To test the influence of this change, we perform a case study where annual mean surface concentrations over Asia are calculated using two different sub-grid scaling factors (ν in equation S1 in the Supplementary Information) determined from one year of observations before and after the resolution change, with other variables held constant. The mean relative difference between the two tests was 9% for grid boxes with annual mean concentrations greater than 1 ppbv, with a change in regional population-weighted NO2 concentrations of 3%. Greater sensitivity to observation resolution was evident in regions with larger NO2 enhancements, although relative differences greater than 25% occur in fewer than 5% of grid boxes. These tests indicate that although the change in observation resolution may change some spatial gradients, the overall impact on population exposure estimates is small.

Uncertainty values presented above represent uncertainty in the conversion of satellite-observed slant columns into surface concentrations and do not represent systematic errors in the retrieval of slant columns from satellite-observed radiances (~10%), or errors in the air mass factor calculations (23–37%), both of which have been extensively examined in prior studies52,65. Errors related to air mass factor calculations can be reduced by using higher-resolution inputs in air mass factor calculations66,67 and are partially mitigated here during the conversion of column densities to surface concentrations through the sub-grid parameterization27.

Although we apply a scaling factor to correct for sampling biases due to persistent cloud cover or surface snow cover, biases in monthly mean calculations may persist if the sampling rate is sufficiently low, particularly for city-level calculations. Most of the cities examined in Supplementary Table 1 had sufficient sampling to allow for a robust monthly mean calculation (median sampling rate of 14 days per month for the months indicated in the table), except for two cities for which fewer than 5 days of observations per month were available for the given month in either 2019 or 2020 (labelled * in Supplementary Table 1). However, results from these cities were consistent with nearby, more frequently sampled cities, lending confidence to these results despite the lower sampling frequency.

This dataset represents substantial improvement over past satellite-derived ground-level NO2 estimates, as the updated algorithm is less sensitive to model resolution and leverages higher-resolution satellite observations than previous estimates. However, limitations remain. There can be considerable fine-scale variability at scales finer than the 1 × 1 km2 resolution used here that cannot be captured by the satellite observations68,69. Additionally, ground-monitor data are used as a constraint in converting observed column densities to ground-level concentrations, and thus absolute concentration values are probably less accurate in time periods or regions where ground-monitor data are unavailable. However, these data are still useful for examining relative interannual variability or trend analysis. In combining OMI and TROPOMI observations we assume that the spatial gradients observed by TROPOMI in 2018–2020 can be applied to OMI for the entire 2005–2019 time series. New or disappearing point emission sources with small plume footprints may affect this assumption; however, past evaluations of similar assumptions have not found it to be a substantial error source25. Additional errors in the column to ground-level conversion may occur in areas with substantial free tropospheric NO2 sources such as aircraft emissions or lightning.

Data availability

TROPOMI-derived 2019 annual mean ground-level NO2 concentrations developed here are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5484305. TROPOMI-derived January–June 2019 and 2020 concentrations are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5484307. Satellite-derived ground-level NO2 concentrations for 2005–2019 used for trend analysis are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5424752. Satellite column data used here are available from the NASA Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (TROPOMI, https://doi.org/10.5270/S5P-s4ljg54; OMI, 10.5067/Aura/OMI/DATA2017). The GEOS-Chem model version used here is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2658178. Hourly ground-level NO2 measurements from ground monitors in the USA are available from the US Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System (https://aqs.epa.gov/aqsweb/documents/data_mart_welcome.html), in Canada from Environment and Climate Change Canada’s National Air Pollution Surveillance Program (http://maps-cartes.ec.gc.ca/rnspa-naps/data.aspx), in Europe from the European Environment Agency (https://aqportal.discomap.eea.europa.eu/index.php/users-corner/), and in China from https://quotsoft.net/air. COVID-19 lockdown policy information is provided by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker#data). Population distribution data are available from the Center for International Earth Science Information Network, https://doi.org/10.7927/H4JW8BX5. NO2 changes during COVID-19 lockdowns from previous studies used for comparison here were compiled by Gkatzelis et al.34 and are available at https://covid-aqs.fz-juelich.de. Gross National Income data were provided by World Bank, available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gnp.pcap.cd?year_high_desc=true.

Code availability

Code used to calculate surface NO2 concentrations from satellite columns is available upon request. Some features in the displayed maps were produced using The Climate Data Toolbox for MATLAB70.

References

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249 (2020).

Pannullo, F. et al. Quantifying the impact of current and future concentrations of air pollutants on respiratory disease risk in England. Environ. Health 16, 29 (2017).

Tao, Y., Mi, S., Zhou, S., Wang, S. & Xie, X. Air pollution and hospital admissions for respiratory diseases in Lanzhou, China. Environ. Pollut. 185, 196–201 (2014).

Zeng, W. et al. Association between NO2 cumulative exposure and influenza prevalence in mountainous regions: a case study from southwest China. Environ. Res. 189, 109926 (2020).

Anenberg, S. C. et al. Estimates of the global burden of ambient PM2.5, ozone, and NO2 on asthma incidence and emergency room visits. Environ. Health Perspect. 126, 107004 (2018).

Achakulwisut, P., Brauer, M., Hystad, P. & Anenberg, S. C. Global, national, and urban burdens of paediatric asthma incidence attributable to ambient NO2 pollution: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e166–e178 (2019).

Hamra, G. B. et al. Lung cancer and exposure to nitrogen dioxide and traffic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 1107–1112 (2015).

Brook, J. R. et al. Further interpretation of the acute effect of nitrogen dioxide observed in Canadian time-series studies. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 17, S36–S44 (2007).

Crouse, D. L. et al. Within-and between-city contrasts in nitrogen dioxide and mortality in 10 Canadian cities; a subset of the Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC). J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 25, 482–489 (2015).

Goldberg, D. L. et al. Disentangling the impact of the COVID‐19 lockdowns on urban NO2 from natural variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089269 (2020).

Biswal, A. et al. COVID-19 lockdown induced changes in NO2 levels across India observed by multi-satellite and surface observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 5235–5251 (2021).

Koukouli, M.-E. et al. Sudden changes in nitrogen dioxide emissions over Greece due to lockdown after the outbreak of COVID-19. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 1759–1774 (2021).

Field, R. D., Hickman, J. E., Geogdzhayev, I. V., Tsigaridis, K. & Bauer, S. E. Changes in satellite retrievals of atmospheric composition over eastern China during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-567 (2020).

Bauwens, M. et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on NO2 pollution assessed using TROPOMI and OMI observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087978 (2020).

Liu, F. et al. Abrupt decline in tropospheric nitrogen dioxide over China after the outbreak of COVID-19. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc2992 (2020).

Prunet, P., Lezeaux, O., Camy-Peyret, C. & Thevenon, H. Analysis of the NO2 tropospheric product from S5P TROPOMI for monitoring pollution at city scale. City Environ. Interact. 8, 100051 (2020).

Shi, X. & Brasseur, G. P. The response in air quality to the reduction of Chinese economic activities during the COVID‐19 Ooutbreak. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088070 (2020).

Ropkins, K. & Tate, J. E. Early observations on the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on air quality trends across the UK. Sci. Total Environ. 754, 142374 (2021).

Fu, F., Purvis-Roberts, K. L. & Williams, B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on air pollution in 20 major cities around the world. Atmosphere 11, 1189 (2020).

Venter, Z. S., Aunan, K., Chowdhury, S. & Lelieveld, J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 18984–18990 (2020).

Levy, I., Mihele, C., Lu, G., Narayan, J. & Brook, J. R. Evaluating multipollutant exposure and urban air quality: pollutant interrelationships, neighborhood variability, and nitrogen dioxide as a proxy pollutant. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 65–72 (2014).

Shi, Z. et al. Abrupt but smaller than expected changes in surface air quality attributable to COVID-19 lockdowns. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6696 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Spatiotemporal changes in global nitrogen dioxide emission due to COVID-19 mitigation policies. Sci. Total Environ. 776, 146027 (2021).

Lamsal, L. N. et al. Ground-level nitrogen dioxide concentrations inferred from the satellite-borne Ozone Monitoring Instrument. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D16308 (2008).

Geddes, J. A., Martin, R. V., Boys, B. L. & van Donkelaar, A. Long-term trends worldwide in ambient NO2 concentrations inferred from satellite observations. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 281–289 (2016).

Gu, J. et al. Ground-level NO2 concentrations over China inferred from the satellite OMI and CMAQ model simulations. Remote Sens. 9, 519 (2017).

Cooper, M. J., Martin, R. V., McLinden, C. A. & Brook, J. R. Inferring ground-level nitrogen dioxide concentrations at fine spatial resolution applied to the TROPOMI satellite instrument. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104013 (2020).

Levelt, P. F. et al. The Ozone Monitoring Instrument: overview of 14 years in space. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 5699–5745 (2018).

Levelt, P. F. et al. The Ozone Monitoring Instrument. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44, 1093–1100 (2006).

Veefkind, J. P. et al. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: a GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 120, 70–83 (2012).

Goldberg, D. L., Anenberg, S., Mohegh, A., Lu, Z. & Streets, D. G. TROPOMI NO2 in the United States: a detailed look at the annual averages, weekly cycles, effects of temperature, and correlation with PM2.5. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1002/essoar.10503422.1 (2020).

Dix, B. et al. Nitrogen oxide emissions from US oil and gas production: recent trends and source attribution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085866 (2020).

Schenkeveld, V. M. E. et al. In-flight performance of the Ozone Monitoring Instrument. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 10, 1957–1986 (2017).

Gkatzelis, G. I. et al. The global impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns on urban air pollution: a critical review and recommendations. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 9, 00176 (2021).

Benítez-García, S.-E., Kanda, I., Wakamatsu, S., Okazaki, Y. & Kawano, M. Analysis of criteria air pollutant trends in three Mexican metropolitan areas. Atmosphere 5, 806–829 (2014).

Duncan, B. N. et al. A space-based, high-resolution view of notable changes in urban NOx pollution around the world (2005–2014). J. Geophys. Res. 121, 976–996 (2016).

Bari, M. & Kindzierski, W. B. Fifteen-year trends in criteria air pollutants in oil sands communities of Alberta, Canada. Environ. Int. 74, 200–208 (2015).

Zheng, B. et al. Trends in China’s anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 14095–14111 (2018).

Georgoulias, A. K., van der, A. R. J., Stammes, P., Boersma, K. F. & Eskes, H. J. Trends and trend reversal detection in 2 decades of tropospheric NO2 satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 6269–6294 (2019).

Krotkov, N. A. et al. Aura OMI observations of regional SO2 and NO2 pollution changes from 2005 to 2015. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 4605–4629 (2016).

Hilboll, A., Richter, A. & Burrows, J. P. NO2 pollution over India observed from space – the impact of rapid economic growth, and a recent decline. Preprint https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2017-101 (2017).

Zhang, R. et al. Comparing OMI-based and EPA AQS in situ NO2 trends: towards understanding surface NOx emission changes. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 3955–3967 (2018).

Lin, N., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Yang, K. A large decline of tropospheric NO2 in China observed from space by SNPP OMPS. Sci. Total Environ. 675, 337–342 (2019).

Barkley, M. P. et al. OMI air-quality monitoring over the Middle East. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 4687–4709 (2017).

Vohra, K. et al. Long-term trends in air quality in major cities in the UK and India: a view from space. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 6275–6296 (2021).

Kerr, G. H., Goldberg, D. L. & Anenberg, S. C. COVID-19 pandemic reveals persistent disparities in nitrogen dioxide pollution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2022409118 (2021).

Le, T. et al. Unexpected air pollution with marked emission reductions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science 369, 702–706 (2020).

Chen, L.-W. A., Chien, L.-C., Li, Y. & Lin, G. Nonuniform impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on air quality over the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 745, 141105 (2020).

Hammer, M. S. et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdowns on fine particulate matter concentrations. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg7670 (2021).

Keller, C. A. et al. Global impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the surface concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and ozone. Atmos. Phys. Chem. 21, 3555–3592 (2021).

Lamsal, L. N. et al. Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) Aura nitrogen dioxide standard product version 4.0 with improved surface and cloud treatments. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 455–479 (2021).

van Geffen, J. et al. S5P TROPOMI NO2 slant column retrieval: method, stability, uncertainties and comparisons with OMI. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 1315–1335 (2020).

Folkert Boersma, K. et al. Improving algorithms and uncertainty estimates for satellite NO2 retrievals: results from the quality assurance for the essential climate variables (QA4ECV) project. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 6651–6678 (2018).

Goldberg, D. L. et al. Enhanced capabilities of TROPOMI NO2: estimating NOx from North American cities and power plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12594–12601 (2019).

Spurr, R. Area-weighting Tessellation For Nadir-Viewing Spectrometers. Internal Technical Note (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 2003).

Zhu, L. et al. Formaldehyde (HCHO) as a hazardous air pollutant: mapping surface air concentrations from satellite and inferring cancer risks in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5650–5657 (2017).

Bey, I. et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 23073–23095 (2001).

Park, R. J., Jacob, D. J., Field, B. D., Yantosca, R. M. & Chin, M. Natural and transboundary pollution influences on sulfate‐nitrate‐ammonium aerosols in the United States: implications for policy. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D15204 (2004).

Rienecker, M. M. et al. MERRA: NASA’s Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications. J. Clim. 24, 3624–3648 (2011).

Hammer, M. S. et al. Global estimates and long-term trends of fine particulate matter concentrations (1998–2018). Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7879–7890 (2020).

Gatz, D. F. & Smith, L. The standard error of a weighted mean concentration—I. Bootstrapping vs other methods. Atmos. Environ. 29, 1185–1193 (1995).

Chimot, J., Vlemmix, T., Veefkind, J. P., de Haan, J. F. & Levelt, P. F. Impact of aerosols on the OMI tropospheric NO2 retrievals over industrialized regions: how accurate is the aerosol correction of cloud-free scenes via a simple cloud model? Atmos. Meas. Tech. 9, 359–382 (2016).

Lin, J.-T. et al. Retrieving tropospheric nitrogen dioxide from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument: effects of aerosols, surface reflectance anisotropy, and vertical profile of nitrogen dioxide. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 1441–1461 (2014).

Cooper, M. J., Martin, R. V., Hammer, M. S. & McLinden, C. A. An observation‐based correction for aerosol effects on nitrogen dioxide column retrievals using the Absorbing Aerosol Index. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 8442–8452 (2019).

Verhoelst, T. et al. Ground-based validation of the Copernicus Sentinel-5P TROPOMI NO2 measurements with the NDACC ZSL-DOAS, MAX-DOAS and Pandonia global networks. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 481–510 (2021).

Laughner, J. L., Zare, A. & Cohen, R. C. Effects of daily meteorology on the interpretation of space-based remote sensing of NO2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 15247–15264 (2016).

Liu, S. et al. An improved air mass factor calculation for nitrogen dioxide measurements from the Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment-2 (GOME-2). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 755–787 (2020).

Judd, L. M. et al. Evaluating the impact of spatial resolution on tropospheric NO2 column comparisons within urban areas using high-resolution airborne data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 6091–6111 (2019).

Kharol, S. K. et al. Assessment of the magnitude and recent trends in satellite-derived ground-level nitrogen dioxide over North America. Atmos. Environ. 118, 236–245 (2015).

Greene, C. A. et al. The Climate Data Toolbox for MATLAB. Geochem. Gheophys. Geosyst. 20, 3774–3781 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Environment and Climate Change Canada and by the Canadian Urban Environmental Health Research Consortium. R.V.M. acknowledges support from NASA grants 80NSSC21K1343 and 80NSSC21K0508. We thank the OMI instrument team, and the OMI and TROPOMI teams for making NO2 data publicly available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.C. and R.V.M. designed the study. M.J.C. performed the analysis. M.S.H. performed GEOS-Chem model simulations and developed the PM2.5 data used here. P.F.L. and P.V. developed and provided the TROPOMI NO2 data used here. L.N.L. and N.A.K. developed and provided the OMI NO2 data used here. M.J.C. prepared the manuscript with contributions from R.V.M., M.S.H., P.F.L., P.V., L.N.L., N.A.K., J.R.B. and C.A.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figures 1–20, and additional references.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, M.J., Martin, R.V., Hammer, M.S. et al. Global fine-scale changes in ambient NO2 during COVID-19 lockdowns. Nature 601, 380–387 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04229-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04229-0

This article is cited by

-

Trans-boundary spatio-temporal analysis of Sentinel 5P tropospheric nitrogen dioxide and total carbon monoxide columns over Punjab and Haryana Regions with COVID-19 lockdown impact

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2024)

-

Underestimated benefits of NOx control in reducing SNA and O3 based on missing heterogeneous HONO sources

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2024)

-

Does urban particulate matter hinder COVID-19 transmission rate?

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2024)

-

Artificial intelligence for improving Nitrogen Dioxide forecasting of Abu Dhabi environment agency ground-based stations

Journal of Big Data (2023)

-

Near-real-time global gridded daily CO2 emissions 2021

Scientific Data (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.