Abstract

Spin-triplet superconductors are condensates of electron pairs with spin 1 and an odd-parity wavefunction1. An interesting manifestation of triplet pairing is the chiral p-wave state, which is topologically non-trivial and provides a natural platform for realizing Majorana edge modes2,3. However, triplet pairing is rare in solid-state systems and has not been unambiguously identified in any bulk compound so far. Given that pairing is usually mediated by ferromagnetic spin fluctuations, uranium-based heavy-fermion systems containing f-electron elements, which can harbour both strong correlations and magnetism, are considered ideal candidates for realizing spin-triplet superconductivity4. Here we present scanning tunnelling microscopy studies of the recently discovered heavy-fermion superconductor UTe2, which has a superconducting transition temperature of 1.6 kelvin5. We find signatures of coexisting Kondo effect and superconductivity that show competing spatial modulations within one unit cell. Scanning tunnelling spectroscopy at step edges reveals signatures of chiral in-gap states, which have been predicted to exist at the boundaries of topological superconductors. Combined with existing data that indicate triplet pairing in UTe2, the presence of chiral states suggests that UTe2 is a strong candidate for chiral-triplet topological superconductivity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mackenzie, A. P. & Maeno, Y. The superconductivity of Sr2RuO4 and the physics of spin-triplet pairing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 657–712 (2003).

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076501 (2017).

Read, N. & Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267 (2000).

Aoki, D., Ishida, K. & Flouquet, J. Review of U-based ferromagnetic superconductors: comparison between UGe2, URhGe, and UCoGe. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 022001 (2019).

Ran, S. et al. Nearly ferromagnetic spin-triplet superconductivity. Science 365, 684–687 (2019).

Leggett, A. J. A theoretical description of the new phases of liquid 3He. Rev. Mod. Phys. 47, 331 (1975); erratum 48, 357 (1976).

Kallin, C. Chiral p-wave order in Sr2RuO4. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 042501 (2012).

Ishida, K. et al. Spin-triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4 identified by 17O Knight shift. Nature 396, 658–660 (1998).

Pustogow, A. et al. Constraints on the superconducting order parameter in Sr2RuO4 from oxygen-17 nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature 574, 72–75 (2019).

Stewart, G. R., Fisk, Z., Willis, J. O. & Smith, J. L. Possibility of coexistence of bulk superconductivity and spin fluctuations in UPt3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 679–682 (1984).

Saxena, S. S. et al. Superconductivity on the border of itinerant-electron ferromagnetism in UGe2. Nature 406, 587–592 (2000).

Aoki, D. et al. Coexistence of superconductivity and ferromagnetism in URhGe. Nature 413, 613–616 (2001).

Huy, N. T. et al. Superconductivity on the border of weak itinerant ferromagnetism in UCoGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 067006 (2007).

Aoki, D. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in heavy fermion UTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 043702 (2019).

Ran, S. et al. Extreme magnetic field-boosted superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 15, 1250–1254 (2019).

Knebel, G. et al. Field-reentrant superconductivity close to a metamagnetic transition in the heavy-fermion superconductor UTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 063707 (2019).

Sundar, S. et al. Coexistence of ferromagnetic fluctuations and superconductivity in the actinide superconductor UTe2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 140502 (2019).

Tokunaga, Y. et al. 125Te-NMR study on a single crystal of heavy fermion superconductor UTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 073701 (2019).

Madhavan, V., Chen, W., Jamneala, T., Crommie, M. F. & Wingreen, N. S. Tunneling into a single magnetic atom: spectroscopic evidence of the Kondo resonance. Science 280, 567–569 (1998).

Maltseva, M., Dzero, M. & Coleman, P. Electron cotunneling into a Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 206402 (2009).

Ernst, S. et al. Emerging local Kondo screening and spatial coherence in the heavy-fermion metal YbRh2Si2. Nature 474, 362–366 (2011).

Gyenis, A. et al. Visualizing heavy fermion confinement and Pauli limited superconductivity in layered CeCoIn5. Nat. Commun. 9, 549 (2018).

Jiao, L. et al. Additional energy scale in SmB6 at low temperature. Nat. Commun. 7, 13762 (2016).

Kashiwaya, S. et al. Edge states of Sr2RuO4 detected by in-plane tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 077003 (2011).

Yamashiro, M., Tanaka, Y. & Kashiwaya, S. Theory of tunneling spectroscopy in superconducting Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. B 56, 7847–7850 (1997).

Honerkamp, C. & Sigrist, M. Andreev reflection in unitary and non-unitary triplet states. J. Low Temp. Phys. 111, 895–915 (1998).

Kobayashi, S., Tanaka, Y. & Sato, M. Fragile surface zero-energy flat bands in three-dimensional chiral superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 214514 (2015).

Fano, U. Effects of configuration interaction on intensities and phase shifts. Phys. Rev. 124, 1866–1878 (1961).

Schmidt, A. R. et al. Imaging the Fano lattice to ‘hidden order’ transition in URu2Si2. Nature 465, 570–576 (2010).

Aynajian, P. et al. Visualizing the formation of the Kondo lattice and the hidden order in URu2Si2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10383–10388 (2010).

Tranquada, J. M., Sternlieb, B. J., Axe, J. D., Nakamura, Y. & Uchida, S. Evidence for stripe correlations of spins and holes in copper oxide superconductors. Nature 375, 561–563 (1995).

Hamidian, M. H. et al. Detection of a Cooper-pair density wave in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x. Nature 532, 343–347 (2016).

Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Arrested Kondo effect and hidden order in URu2Si2. Nat. Phys. 5, 796–799 (2009).

Kashiwaya, S. & Tanaka, Y. Tunnelling effects on surface bound states in unconventional superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 63, 1641 (2000).

Metz, T. et al. Point node gap structure of spin-triplet superconductor UTe2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 220504 (2019).

Hillier, A. D., Quintanilla, J., Mazidian, B., Annett, J. F. & Cywinski, R. Nonunitary triplet pairing in the centrosymmetric superconductor LaNiGa2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 097001 (2012).

Miyake, A. et al. Metamagnetic transition in heavy fermion superconductor UTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 063706 (2019).

Kozii, V., Venderbos, J. W. F. & Fu, L. Three-dimensional Majorana fermions in chiral superconductors. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601835 (2016).

Tamura, S., Kobayashi, S., Bo, L. & Tanaka, Y. Theory of surface Andreev bound states and tunneling spectroscopy in three-dimensional chiral superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 95, 104511 (2017).

Dynes, R. C., Narayanamurti, V. & Garno, J. P. Direct measurement of quasiparticle-lifetime broadening in a strong-coupled superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 1509–1512 (1978).

Singh, U. R., Enayat, M., White, S. C. & Wahl, P. Construction and performance of a dilution-refrigerator based spectroscopic-imaging scanning tunneling microscope. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 84, 013708 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank T. L. Hughes, Y. Tanaka, N. Mason, D. Van Harlingen, P. Abbamonte, C. Kallin, Y. Yanase, O. Erten, R. Flint, Y. Wang, J. C. Davis, L. Hu and R. Huang for discussions. The work at UIUC was supported by a grant from the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under award number DE-SC0014335. V.M. acknowledges partial support from Gordon and Betty More Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative through grant GBMF4860. Z.W. is supported by the US Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences through grant number DE-FG02-99ER45747. The work at UMD was supported by NIST. M.S. was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation through Division II, number 184739.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.M., N.P.B. and L.J. conceived the experiments. L.J., Z.W. and J.O.R. obtained the STM data and characterized the samples. L.J., S.H., M.S., Z.W. and V.M. performed the data analysis and wrote the paper. S.R. and N.P.B. provided the characterized single crystals.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Xi Chen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

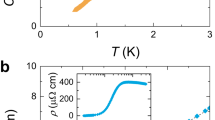

Extended Data Fig. 1 High quality of UTe2 single crystal.

a, Optical micrograph of a UTe2 single crystal after being cut along the a axis. The exposed (0−11) surface is flat and shiny with several step edges along the a axis. b, Laue diffraction pattern of one UTe2 single crystal, with selected (hkl) surfaces marked. The same crystal was used for the specific-heat and STS measurements presented in c. c, Specific heat of UTe2, showing a pronounced single jump around 1.6 K. The specific-heat jump at Tsc is particularly large, indicating bulk superconductivity of heavy electrons. The specific-heat measurement and the temperature-dependent STS measurement shown in Fig. 1d were conducted on the same sample, indicating a well defined superconducting phase of UTe2.

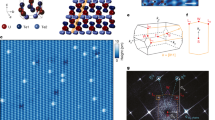

Extended Data Fig. 2 Crystal structure and cleaved plane of UTe2.

a, Crystal structure of UTe2. The lattice parameters are a = 4.161 Å, b = 6.122 Å and c = 13.955 Å. b, The primitive cell of UTe2 with the nearest bond distances between U and Te1, Te2 are denoted in the figure. c, (100) view of the crystal showing the cleaved plane, which is between the primitive cells and breaks the next-nearest U–Te1 bond (3.201 Å). d, Top view of the cleaved (0−11) plane. e, Typical STM topography image of a sample with multiple random distributed step edges. f, Height profile along the orange dashed line in the centre of c. The height of the step edge is ~5.5 Å. g, A 8 × 8 nm2 topography image showing chains of Te1 and Te2 along the a axis. h, Height profile measured along the red dashed line in g. The periodicity of the height profile fits very well with the lattice parameters in d. The step heights and the atomic spacings are consistent with the identification of the cleaved surface as the (0−11) plane.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Large-energy LDOS of UTe2.

a. dI/dV curve of UTe2 obtained at 0.3K from 500 mV to −500 mV. The curve follows a V-shape at higher energies and drops close to zero around zero bias. The almost zero DOS at EF suggests that this material is close to being a Kondo insulator. b, A fit of the spatially averaged dI/dV-curve to the Fano model: \(\frac{{\rm{d}}I}{{\rm{d}}V}(V)\propto \frac{{[(V-{E}_{0})/\varGamma +{q}_{{\rm{K}}}]}^{2}}{1+{[(V-{E}_{0})/\varGamma ]}^{2}}\). Red and black curves are the raw data and the fitted curve, respectively. The fitting parameters are qK = 0.57(2), E0 = 0.70(8) meV and Γ = 3.60(6) meV, and the uncertainties were derived from the standard errors of our fitting. Blue dashed lines are simple extrapolations (linear for Vb > 0 and quadratic for Vb < 0) of the V-shaped background, which are subtracted from the spectra, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 5b, for further analysis. arb. u., arbitrary units.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Phenomenology of the superconducting gap of UTe2.

a, Comparison of the superconducting-gap structure of UTe2 obtained with a tungsten tip (W-tip) and a UTe2 tip (a W tip with a UTe2 flake at the apex) with data on superconducting MoTe1.85S0.15. The spectra were all obtained using the same STM system at ~0.3 K without an external magnetic field. MoTe1.85S0.15 has Tsc ≈ 2.2 K and a gap of Δ ≈ 0.3 meV, slightly larger than UTe2. In UTe2, the LDOS at zero bias drops by only 5–10% compared with its normal-state DOS, whereas it drops by ~80% in MoTe1.85S0.15. Even in the data measured by the UTe2 tip, which show a larger gap than MoTe1.85S0.15, the LDOS drop is smaller. Given that all the data were collected with similar tunnelling parameters and by the same STM system, the large residual LDOS in UTe2 is unlikely to be a simple thermal broadening effect or to be due to some external artefact. b, Magnetic-field-dependent dI/dV curves at 0.3 K. As discussed in the main text, the intrinsic superconducting gap is small. Therefore, tracking the superconducting-gap structure in a high magnetic field is challenging. Instead, we present the data obtained with a superconducting tip. The figure shows that the superconducting gap is continuously suppressed up to 10 T. Because Tsc is around 1.6 K, this result suggests a large upper critical field of UTe2, exceeding the Pauli limit of 1.86Tsc. Meanwhile, the derived upper critical field of ~10 T is consistent with transport measurements with the field perpendicular to the (0−11) plane.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Analyses of the Kondo lattice peak.

a, Fits to the Kondo resonance feature obtained as a function of position from Te1 (site A) to Te2 (site E) (see main text). Curves are fitted to the Fano line shape. The fitting parameters are summarized in Extended Data Table 1. The Kondo temperature TK can be derived from Γ = kBTK (kB, Boltzmann constant). As shown in the table, TK varies from ~19.6 K to 26 K. b, The LDOS (dI/dV) obtained by subtracting a V-shaped background (dashed blue lines in Extended Data Fig. 3). c, Simulation of dI/dV by a Kondo lattice model with a quantum cotunnelling effect. The model used here was proposed by Maltseva et al.2, \(\frac{{\rm{d}}I}{{\rm{d}}V}(V)={\rm{IM}}\left[{\left(1+\frac{vq}{V-{\rm{i}}\gamma -{E}_{0}}\right)}^{2}\,\log \left(\frac{V-{\rm{i}}\gamma +D1-\frac{{v}^{2}}{V-{\rm{i}}\gamma -{E}_{0}}}{V-{\rm{i}}\gamma -D2-\frac{{v}^{2}}{V-{\rm{i}}\gamma -{E}_{0}}}\right)+\frac{(D1+D2){q}^{2}}{V-{\rm{i}}\gamma -{E}_{0}}\right]\), where the definitions of E0, q are the same as those in the Fano model, −D1 and D2 are the energy levels of the lower and upper conduction band edges, respectively, v is the hybridization amplitude, and γ is the self-energy. For simplicity, we take the same E0, q from Extended Data Table 2. D1 ≈ 3 eV is obtained from angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Then the remaining free parameters are D2, v and γ. Extended Data Table 2 presents the fitting parameters. Given the Kondo hybridization gap ΔK = 2v2/(D1 + D2), we also calculated the hybridization gap size in Extended Data Table 2, which is comparable to Γ in Extended Data Table 1.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Analyses of the superconducting gap.

a, Fits to a series of superconducting gaps obtained at the positions shown in the inset as we move from Te1 (site A) to Te2 (site E). The dI/dV curves are fitted with the Dynes function including the thermal broadening effect40,41: \(\frac{{\rm{d}}I}{{\rm{d}}V}(V)={N}_{0}\int {\rm{Re}}\left[\frac{V+\omega +{\rm{i}}G}{\sqrt{{(V+\omega +{\rm{i}}G)}^{2}-{{\Delta }}^{2}(\theta ,\varphi )}}\right]\left(-\frac{\partial f}{\partial \omega }\right){\rm{d}}\omega +{N}_{{\rm{u}}}\), where f is the Fermi–Dirac distribution function at 0.3 K, N0 is proportional to the LDOS in the normal state, Nu is related to the residual LDOS dominated by unpaired electrons, which is set at 0.5 based on the specific-heat data, and G quantifies the effect of the pair-breaking processes, which is related to the quasiparticle lifetime (ω, energy; θ, polar angle; ϕ, azimuthal angle). The most important parameter here is the superconducting-gap function Δ(θ, ϕ). Here, we tried both the s-wave gap Δ(θ, ϕ) = Δ0 and the proposed spin-triplet px + ipy gap \({\Delta }({\theta },\varphi )={{\Delta }}_{0}|{\hat{k}}_{x}+{\rm{i}}{\hat{k}}_{y}|\). As Nu is approximately 50% of N0, the derived gap sizes Δ0 at each site are similar for the s- and p-wave gap functions. The fit parameters are summarized in Extended Data Table 3. For both s- and p-wave gap functions, Δ0 increases about 2.7 times from site A to site E, while G shows much smaller changes. b, Spatial variation of the superconducting gap from one Te2 chain to the next Te2 chain. Oscillations of the coherence peak and the zero-bias LDOS are shown in the figure.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Robustness of the Kondo effect and ‘chirality’ of the tunnelling current around the step edge.

a, Topography image with a [0−1−1] step edge. b, dI/dV curves along the black arrow in a, obtained at nine points equally distributed within 2 nm. The results shown in b reveal a weak modulation of the Kondo effect, consistent with Extended Data Fig. 5. Importantly, no clear change of the energy level of the Kondo lattice peak is observed around the step edge when the asymmetric edge states appear. Therefore, the in-gap states coexist with the Kondo effect in UTe2. c, Topography image showing that a step edge can terminate at either Te1 or Te2 chains. d, dI/dV spectra obtained on Te2 and Te1 sites. The two spectra obtained at Te2- and Te1-terminated step edges shown in c are similar, with the peak always appearing at negative bias, indicating that the ‘chirality’ of the tunnelling current is robust against local step-edge termination.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Schematic of momentum-selective tunnelling on a step edge.

a, Schematic illustration of a sample showing the orientations of the a axis (which coincides with the chiral axis, \(\hat{c}\)) and the momentum K (spontaneous current direction). b, For a chiral superconductor, a quasi-linear dispersive chiral in-gap state (dark blue line) is expected to reside on the surface layers. c, On the step edge, the momentum distributions of incident tunnelling electrons are skewed. In this case, a momentum-selective tunnelling effect is realized close to the step edge, enabling us to tunnel into states with either +k (blue dotted oval) or −k (red dotted oval).

Source data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiao, L., Howard, S., Ran, S. et al. Chiral superconductivity in heavy-fermion metal UTe2. Nature 579, 523–527 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2122-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2122-2

This article is cited by

-

Charge-density wave mediated quasi-one-dimensional Kondo lattice in stripe-phase monolayer 1T-NbSe2

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Unconventional superconductivity in Cr-based compound Pr3Cr10−xN11

npj Quantum Materials (2024)

-

Quasi-2D Fermi surface in the anomalous superconductor UTe2

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Flat bands, strange metals and the Kondo effect

Nature Reviews Materials (2024)

-

Field-induced compensation of magnetic exchange as the possible origin of reentrant superconductivity in UTe2

Nature Communications (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.