THE TOPIC IN BRIEF

• In bottom-up approaches, cellular structures and behaviours are reconstituted from their constituent parts.

• This strategy reduces a complex, living system to a more manageable set of component parts, defined by the researcher.

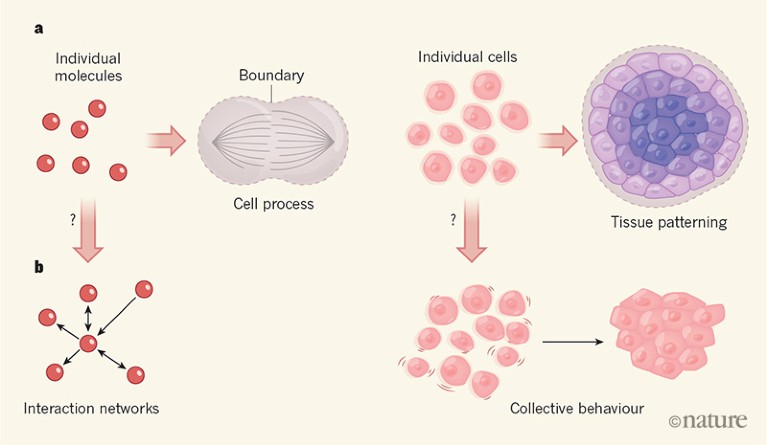

• Bottom-up experiments have provided insights into processes such as cell division, chromosome packaging and tissue patterning (Fig. 1).

• Some researchers believe that any cellular behaviour could eventually be modelled from the bottom up.

• Others, however, argue that this strategy is insufficient for understanding more-complex biological functions that bridge scales of complexity — for example, those in which individual cells act collectively.

Figure 1 | Increasing levels of complexity modelled from the bottom up. a, In in vitro reconstitution, biological parts and processes can be recreated from a minimal set of components. For example, by enclosing individual molecules within specific boundaries, the minimal set of proteins and interactions needed for the emergence of complex phenomena such as cell division can be defined. Likewise, spatial confinement of cells has provided insights into tissue patterning in embryos. b, However, there is debate about whether these bottom-up approaches can provide mechanistic insight into biological processes that bridge scales of complexity — the processes by which thousands of individual molecules interact in cells, for instance, or by which cells act collectively to switch from a fluid-like to a solid-like state.

MATTHEW GOOD: Understanding by building

The complexity of living cells is staggering — their cytoplasm contains tens of thousands of distinct macromolecules and metabolites that must be coordinated to interact in time and space. This intricacy often makes it difficult to interpret results from conventional ‘top-down’ studies, in which individual components are removed or modified. Bottom-up approaches complement investigations of living cells, make it easier to define the rules that govern biological organization, and have provided insights into many previously intractable biological problems.

Biochemical reconstitution has conventionally been used to identify the minimal set of purified factors needed to recapitulate a given cellular activity in vitro. Today, spurred on by advances in materials and engineering, we can carry out more-ambitious cellular reconstitutions. These experiments combine biochemical reconstitution with defined spatial boundaries that can be generated in a range of ways, including through micropatterning and microfabrication of surfaces, and through microfluidic techniques that create compartments surrounded by membranes made up of lipid bilayers or monolayers. The boundaries can be set to either mimic or perturb the natural organization of a cell.

Nature special: Bottom-up biology

Unexpected properties and activities have emerged from the mixing of boundaries and biochemical reactions, leading to new mechanistic insights and extending our ability to model biological processes. For instance, it has been found that encapsulating the motor protein kinesin with filaments called microtubules produces a force-generating network that can propel the movement of cell-size capsules1. This experiment acts as a proof of concept that simplified systems can generate force, and motivates researchers to look for analogous systems in nature, rather than assuming that the solution to this problem in living organisms must always be complex.

As another example, changes in the size and shape of encapsulated compartments — manipulations that are easy in microfabricated systems, but not in living cells — have revealed roles for these parameters in controlling the oscillatory behaviour of proteins involved in cell division2 and the sizes of organelles3. These discoveries act as a potent reminder that experiments carried out in test tubes involve much greater volumes than that of a cell; an absence of boundary conditions might obfuscate underlying biological principles, such as size scaling.

In some cases, biological insight can be gained only by removing boundaries, to simplify the system or enable it to be expanded — another feat not possible in living cells. For example, cytoplasmic extracts from cells have been used to show that chromosomes can condense in preparation for cell division even in the absence of histone proteins, around which DNA is packaged in cells4. Because histones are essential to living cells, such experiments could be performed only ex vivo.

The same cytoplasmic-extract system has also been combined with an elongated chamber (many times longer than a cell) to identify a new class of signalling reaction that spatially coordinates the cell cycle and is based on self-propagating ‘trigger waves’5. These waves, first postulated by mathematical modelling, could be identified and characterized more easily in a deconstructed system containing defined boundary conditions than by in vivo methods.

For bottom-up approaches to further complement and one day even surpass top-down approaches, certain challenges must be addressed. One is deciding which elements of a cell can be removed without limiting the biological relevance of the findings. Another is to identify empirical approaches to validate whether rules derived from in vitro experiments are predictive for in vivo situations. A third is that we must continue to improve the precision and reliability of engineered boundaries to better mimic those in cells.

Bottom-up reconstitution approaches promise to expand our understanding of biology at higher levels. By continuing to increase the number of components that can be patterned together, it might eventually be possible to reconstruct systems that rival the complexity of living cells and tissues. For example, micropatterning techniques and assembly principles are being used to configure cells in geometries that mimic those found in embryonic development6, and to produce designer tissues7. In these experiments, complex, controllable 3D tissue shapes can be obtained by defining simple interactions between individual cells, between cells and the structural matrix that surrounds them and between proteins involved in tissue patterning. Given well-characterized building blocks, a preliminary understanding of boundary conditions and a reasonable period of time, it should be realistic to consider reconstituting any complex cell behaviour. From there, a new understanding of the rules that underlie biological processes can emerge.

XAVIER TREPAT: Bottom does not explain top

Picture yourself as an engineer in the car industry. You know the role of every bolt, joint and circuit in a car. You have great understanding of the hierarchies and redundancies that ensure smooth functioning of all systems. In a nutshell, you know how to build a car from the bottom up. Now imagine that you are asked to solve the problem of traffic jams during rush hour. Traffic jams are a problem of cars, and you know everything about cars — but this detailed knowledge is irrelevant to understanding why they jam. Similarly, an understanding of how complex biological structures or even whole cells are built can provide only a certain level of understanding about how biological systems function at higher levels of organization.

Much like cars in traffic, cells can jam. At low density, cells grown in culture move and exchange neighbours frequently, like molecules in a fluid. But at higher densities, cellular movements slow down, rearrangements vanish, and the system jams into a solid-like state8. Other variables can also cause cell jamming — when cultured at the same density, epithelial cells obtained from people with asthma move collectively, like a fluid, whereas their healthy counterparts jam9. Cell jamming also occurs in vivo, and is key to the normal elongation of zebrafish embryos during development10.

Jamming is a prominent example of a mesoscale phenomenon — a process that operates at a longer scale than do the elementary components of a system — in which ‘bottom’ does not explain ‘top’. It is unlikely that being able to reconstitute the differing protein pathways in healthy and asthmatic cells will explain why one jams more easily than the other. In fact, the most predictive variable for cell jamming is the shape index, a geometric quantity defined as the ratio of the cell’s perimeter to the square root of its area9. Similarly, it is also unlikely that the genetic programs that are turned on and off during development will explain why cells jam as the vertebrate body elongates.

Another example of a process in which mechanisms at the bottom cannot explain phenomena at the top is collective gradient sensing, whereby a group can sense and respond to an environmental gradient but individual constitutive elements cannot. Collective gradient sensing has been observed in a variety of groups undergoing directed migration, including shoals of fish moving in response to light11, clusters of leukaemia cells responding to chemical signals12, and epithelial cells whose migration is guided by a gradient of rigidity13. The reconstitution of each element of these motile groups, no matter how detailed, will never explain why groups move in the direction of the gradient but individual elements do not.

This is not to say, of course, that reconstitution of molecular-scale processes is not useful. Indeed, the engineering of genetic circuits responsible for cell communication is sufficient to control 3D tissue shape14. However, principles at the molecular scale cannot generally explain functions at a higher level of organization.

Well before its discovery in cells, jamming was proposed to tie together liquid-to-solid transitions in a wide range of inert materials such as foams, emulsions and sand piles15. The materials differ broadly in composition, but their physical behaviour can be captured by a simple set of physical variables. These variables configure a phase diagram — a graph that plots whether the system is jammed or unjammed as a function of interaction forces, temperature or density. Like jamming in inert15 and living matter9,10, other biological functions might be explained in terms of phase diagrams. Given the complexity of cells and tissues, the position of a system in those diagrams will be compatible with many different combinations of molecular states, concentrations and interactions.

It is questionable whether trying to understand each of these combinations is an efficient path towards a predictive understanding of complex living systems. Rather, we should aim to identify the mesoscale principles and variables that ultimately determine how these systems work. To do so, we need to develop experimental approaches to probe tissues at multiple length scales and timescales through both mechanical and biochemical manipulation.

Nature special: Bottom-up biology

Nature special: Bottom-up biology

Focus on the benefits of building life’s systems from scratch

Focus on the benefits of building life’s systems from scratch

How biologists are creating life-like cells from scratch

How biologists are creating life-like cells from scratch

Which biological systems should be engineered?

Which biological systems should be engineered?

Cellular stretch reveals superelastic powers

Cellular stretch reveals superelastic powers

Active superelasticity in three-dimensional epithelia of controlled shape

Active superelasticity in three-dimensional epithelia of controlled shape

A constructive debate

A constructive debate

Engineering explored

Engineering explored