Abstract

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is among the world’s earliest domesticated and most important crop plants. It is diploid with a large haploid genome of 5.1 gigabases (Gb). Here we present an integrated and ordered physical, genetic and functional sequence resource that describes the barley gene-space in a structured whole-genome context. We developed a physical map of 4.98 Gb, with more than 3.90 Gb anchored to a high-resolution genetic map. Projecting a deep whole-genome shotgun assembly, complementary DNA and deep RNA sequence data onto this framework supports 79,379 transcript clusters, including 26,159 ‘high-confidence’ genes with homology support from other plant genomes. Abundant alternative splicing, premature termination codons and novel transcriptionally active regions suggest that post-transcriptional processing forms an important regulatory layer. Survey sequences from diverse accessions reveal a landscape of extensive single-nucleotide variation. Our data provide a platform for both genome-assisted research and enabling contemporary crop improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Cultivated barley, derived from its wild progenitor Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum, is among the world’s earliest domesticated crop species1 and today represents the fourth most abundant cereal in both area and tonnage harvested (http://faostat.fao.org). Approximately three-quarters of global production is used for animal feed, 20% is malted for use in alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, and 5% as an ingredient in a range of food products2. Barley is widely adapted to diverse environmental conditions and is more stress tolerant than its close relative wheat3. As a result, barley remains a major food source in poorer countries4, maintaining harvestable yields in harsh and marginal environments. In more developed societies it has recently been classified as a true functional food. Barley grain is particularly high in soluble dietary fibre, which significantly reduces the risk of serious human diseases including type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancers that afflict hundreds of millions of people worldwide5. The USA Food and Drug Administration permit a human health claim for cell-wall polysaccharides from barley grain.

As a diploid, inbreeding, temperate crop, barley has traditionally been considered a model for plant genetic research. Large collections of germplasm containing geographically diverse elite varieties, landraces and wild accessions are readily available6 and undoubtedly contain alleles that could ameliorate the effect of climate change and further enhance dietary fibre in the grain. Enriching its broad natural diversity, extensive characterized mutant collections containing all of the morphological and developmental variation observed in the species have been generated, characterized and meticulously maintained. The major impediment to the exploitation of these resources in fundamental and breeding science has been the absence of a reference genome sequence, or an appropriate enabling alternative. Providing either of these has been the primary research challenge to the global barley community.

In response to this challenge, we present a novel model for delivering the genome resources needed to reinforce the position of barley as a model for the Triticeae, the tribe that includes bread and durum wheats, barley and rye. We introduce the barley genome gene space, which we define as an integrated, multi-layered informational resource that provides access to the majority of barley genes in a highly structured physical and genetic framework. In association with comparative sequence and transcriptome data, the gene space provides a new molecular and cellular insight into the biology of the species, providing a platform to advance gene discovery and genome-assisted crop improvement.

A sequence-enriched barley physical map

We constructed a genome-wide physical map of the barley cultivar (cv.) Morex by high-information-content fingerprinting7 and contig assembly8 of 571,000 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones (∼14-fold haploid genome coverage) originating from six independent BAC libraries9. After automated assembly and manual curation, the physical map comprised 9,265 BAC contigs with an estimated N50 contig size of 904 kilobases and a cumulative length of 4.98 Gb (Methods, Supplementary Note 2). It is represented by a minimum tiling path (MTP) of 67,000 BAC clones. Given a genome size of 5.1 Gb10, more than 95% of the barley genome is represented in the physical map, comparing favourably to the 1,036 contigs that represent 80% of the 1 Gb wheat chromosome 3B11.

We enhanced the physical map by integrating shotgun sequence information from 5,341 gene-containing12,13 and 937 randomly selected BAC clones (Methods, Supplementary Notes 2 and 3, and Supplementary Table 4), and 304,523 BAC-end sequence (BES) pairs (Supplementary Table 3). These provided 1,136 megabases (Mb) of genomic sequence integrated directly into the physical map (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). This framework facilitated the incorporation of whole-genome shotgun sequence data and integration of the physical and genetic maps. We generated whole-genome shotgun sequence data from genomic DNA of cv. ‘Morex’ by short-read Illumina GAIIx technology, using a combination of 300 base pairs (bp) paired-end and 2.5 kb mate-pair libraries, to >50-fold haploid genome coverage (Supplementary Note 3.3). De novo assembly resulted in sequence contigs totalling 1.9 Gb. Due to the high proportion of repetitive DNA, a substantial part of the whole-genome shotgun data collapsed into relatively small contigs characterized by exceptionally high read depths. Overall, 376,261 contigs were larger than 1 kb (N50 = 264,958 contigs, N50 length = 1,425 bp). Of these, 112,989 (308 Mb) could be anchored directly to the sequence-enriched physical map by sequence homology.

We implemented a hierarchical approach to further anchor the physical and genetic maps (Methods, Supplementary Note 4). A total of 3,241 genetically mapped gene-based single-nucleotide variants (SNV) and 498,165 sequence-tag genetic markers14 allowed us to use sequence homology to assign 4,556 sequence-enriched physical map contigs spanning 3.9 Gb to genetic positions along each barley chromosome. An additional 1,881 contigs were assigned to chromosomal bins by sequence homology to chromosome-arm-specific sequence data sets15 (Supplementary Note 4.4). Thus, 6,437 physical map contigs totalling 4.56 Gb (90% of the genome), were assigned to chromosome arm bins, the majority in linear order. Non-anchored contigs were typically short and lacked genetically informative sequences required for positional assignment.

Consistent with genome sequences of other grass species16 the peri-centromeric and centromeric regions of barley chromosomes exhibit significantly reduced recombination frequency, a feature that compromises exploitation of genetic diversity and negatively impacts genetic studies and plant breeding. Approximately 1.9 Gb or 48% of the genetically anchored physical map (3.9 Gb) was assigned to these regions (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 11).

Track a gives the seven barley chromosomes. Green/grey colour depicts the agreement of anchored fingerprint (FPC) contigs with their chromosome arm assignment based on chromosome-arm-specific shotgun sequence reads (for further details see Supplementary Note 4). For 1H only whole-chromosome sequence assignment was available. Track b, distribution of high-confidence genes along the genetic map; track c, connectors relate gene positions between genetic and the integrated physical map given in track d. Position and distribution of track e class I LTR-retroelements and track f class II DNA transposons are given. Track g, distribution and positioning of sequenced BACs.

Repetitive nature of the barley genome

A characteristic of the barley genome is the abundance of repetitive DNA17. We observed that approximately 84% of the genome is comprised of mobile elements or other repeat structures (Supplementary Note 5). The majority (76% in random BACs) of these consists of retrotransposons, 99.6% of which are long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons. The non-LTR retrotransposons contribute only 0.31% and the DNA transposons 6.3% of the random BAC sequence. In the fraction of the genome with a high proportion of repetitive elements, the LTR Gypsy retrotransposon superfamily was 1.5-fold more abundant than the Copia superfamily, in contrast to observations in both Brachypodium18 and rice19. However, gene-bearing BACs were slightly depleted of retrotransposons, consistent with Brachypodium18 where young Copia retroelements are preferentially found in gene-rich, recombinogenic regions from which inactive Gypsy retroelements have been lost by LTR–LTR recombination. Overall, we see reduced repetitive DNA content within the terminal 10% of the physical map of each barley chromosome arm (Fig. 1). Class I and II elements show non-quantitative reverse-image distribution along barley chromosomes (Fig. 1), a feature shared with other grass genomes16,20 and shown by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) mapping17. Not surprisingly, the whole-genome shotgun assembly shows a lower abundance of LTR retrotransposons (average 53%) than gene-bearing BACs. That LTR retrotransposons are long (∼10 kb), highly repetitive and often nested21 supports our assumption that short reads either collapsed or did not assemble. Short interspersed elements (SINEs)22, short (80–600 bp) non-autonomous retrotransposons that are highly repeated in barley, showed no differential exclusion from the assemblies. However, miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs), small non-autonomous DNA transposons23, were twofold enriched in the whole-genome shotgun assemblies compared with BES reads or random BACs, consistent with the gene richness of the assemblies and their association with genes23. Both MITEs and SINEs are 1.5 to 2-fold enriched in gene-bearing BACs which could indicate that SINEs are also preferentially integrated into gene-rich regions, or because they are older than LTR retroelements, may simply remain visible in and around genes where retro insertions have been selected against.

Transcribed portion of the barley genome

The transcribed complement of the barley gene space was annotated by mapping 1.67 billion RNA-seq reads (167 Gb) obtained from eight stages of barley development as well as 28,592 barley full-length cDNAs24 to the whole-genome shotgun assembly (Methods, Supplementary Notes 6, 7 and Supplementary Tables 20–22). Exon detection and consensus gene modelling revealed 79,379 transcript clusters, of which 75,258 (95%) were anchored to the whole-genome shotgun assembly (Supplementary Notes 7.1.1 and 7.1.2). Based on a gene-family-directed comparison with the genomes of Sorghum, rice, Brachypodium and Arabidopsis, 26,159 of these transcribed loci fall into clusters and have homology support to at least one reference genome (Supplementary Fig. 16); they were defined as high-confidence genes. Comparison against a data set of metabolic genes in Arabidopsis thaliana25 indicated a detection rate of 86%, allowing the barley gene-set to be estimated as approximately 30,400 genes. Due to lack of homology and missing support from gene family clustering, 53,220 transcript loci were considered low-confidence (Table 1). High-confidence and low-confidence barley genes exhibited distinct characteristics: 75% of the high-confidence genes had a multi-exon structure, compared with only 27% of low-confidence genes (Table 1). The mean size of high-confidence genes was 3,013 bp compared with 972 bp for low-confidence genes. A total of 14,481 low-confidence genes showed distant homology to plant proteins in public databases (Supplementary Notes 7.1.2, 7.1.4 and Supplementary Fig. 18), identifying them as potential gene fragments known to populate Triticeae genomes at high copy number and that often result from transposable element activity26.

A total of 15,719 high-confidence genes could be directly associated with the genetically anchored physical map (Supplementary Note 4). An additional 3,743 were integrated by invoking a conservation of synteny model (Supplementary Note 4.5) and a further 4,692 by association with chromosome arm whole-genome shotgun data (Supplementary Note 4.4 and Supplementary Table 15). Importantly, the N50 length of whole-genome shotgun sequence contigs containing high-confidence genes was 8,172 bp, which is generally sufficient to include the entire coding sequence, and 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). Overall 24,154 high-confidence genes (92.3%) were associated and positioned in the physical/genetic scaffold, representing a gene density of five genes per Mb. Proximal and distal ends of chromosomes are more gene-rich, on average containing 13 genes per Mb (Fig. 1).

In comparison with sequenced model plant genomes, gene family analysis (Supplementary Note 7.1.3) revealed some gene families that exhibited barley-specific expansion. We defined the functions of members of these families using gene ontology (GO) and PFAM protein motifs (Supplementary Table 25). Gene families with highly overrepresented GO/PFAM terms included genes encoding (1,3)-β-glucan synthases, protease inhibitors, sugar-binding proteins and sugar transporters. NB-ARC (a nucleotide-binding adaptor shared by APAF-1, certain R gene products and CED-427) domain proteins, known to be involved in defence responses, were also overrepresented, including 191 NBS-LRR type genes. These tended to cluster towards the distal regions of barley chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 17), including a major group on barley chromosome 1HS, co-localizing with the MLA powdery mildew resistance gene cluster28. Biased allocation to recombination-rich regions provides the genomic environment for generating sequence diversity required to cope with dynamic pathogen populations29,30. It is noteworthy that the highly over-represented (1,3)-β-glucan synthase genes have also been implicated in plant–pathogen interactions31.

Regulation of gene expression

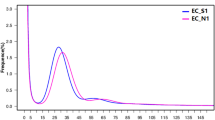

Deep RNA sequence data (RNA-seq) provided insights into the spatial and temporal regulation of gene expression (Supplementary Note 7.2). We found 72–84% of high-confidence genes to be expressed in all spatiotemporal RNA-seq samples (Fig. 2a), slightly lower than reported for rice32 where ∼95% of transcripts were found in more than one developmental or tissue sample. More importantly, 36–55% of high-confidence barley genes seemed to be differentially regulated between samples (Fig. 2b), highlighting the inherent dynamics of barley gene expression.

a, Barley gene expression in different spatial and temporal RNA-seq samples (Supplementary Notes 6, 7). Numbers refer to high-confidence genes. b, Dendrogram depicting relatedness of samples and colour-coded matrix showing number of significantly upregulated high-confidence genes in pairwise comparisons. Σ, total number of non-redundant high-confidence genes upregulated in comparison to all other samples. Height, complete linkage cluster distance (log2(fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped)); see Supplementary Note 7.2.5.1. c, Distribution and overlap of alternatively spliced barley transcripts between RNA-seq samples. d, Distribution and overlap of alternative splicing transcripts fulfilling criteria for PTC+ as detected in different spatial and temporal RNA-seq samples (Supplementary Note 7.4).

Two notable features support the importance of post-transcriptional processing as a central regulatory layer (Supplementary Notes 7.3 and 7.4). First, we observed evidence for extensive alternative splicing. Of the intron-containing high-confidence barley genes, 73% had evidence of alternative splicing (55% of the entire high-confidence set). The spatial and temporal distribution of alternative splicing transcripts deviated significantly from the general occurrence of transcripts in the different tissues analysed (Fig. 2c). Only 17% of alternative splicing transcripts were shared among all samples, and 17–27% of the alternative splicing transcripts were detected only in individual samples, indicating pronounced alternative splicing regulation. We found 2,466 premature termination codon-containing (PTC+) alternative splicing transcripts (9.4% of high-confidence genes) (Fig. 2d and Table 2), similar to the percentage of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)-controlled genes in a wide range of species33,34. Premature termination codons activate the NMD pathway35, which leads to rapid degradation of PTC+ transcripts, and have been associated with transcriptional regulation during disease and stress response in human and Arabidopsis, respectively34,36,37,38,39. The distribution of PTC+ transcripts was strikingly dissimilar, both spatially and temporally, with only 7.4% shared and between 31% and 40% exclusively observed in only a single sample (Fig. 2d). Genes encoding PTC+-containing transcripts show a broad spectrum of GO terms and PFAM domains and are more prevalent in expanded gene families. These observations support a central role for alternative splicing/NMD-dependent decay of PTC+ transcripts as a mechanism that controls the expression of many different barley genes.

Second, recent reports have highlighted the abundance of novel transcriptionally active regions in rice that lack homology to protein-coding genes or open reading frames (ORFs)40. In barley as many as 27,009 preferentially single-exon low-confidence genes can be classified as putative novel transcriptionally active regions (Supplementary Note 7.1.4). We investigated their potential significance by comparing the homology of barley novel transcriptionally active regions with the rice and Brachypodium genomes that respectively represent 50 and 30 million years of evolutionary divergence18. A total of 4,830 and 2,450 novel transcriptionally active regions yielded a homology match to the Brachypodium and rice genomes, respectively (intersection of 2,046; BLAST P value ≤ 10−5), indicating a putative functional role in pre-mRNA processing or other RNA regulatory processes41,42.

Natural diversity

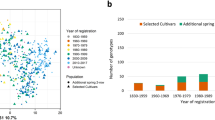

Barley was domesticated approximately 10,000 years ago1. Extensive genotypic analysis of diverse germplasm has revealed that restricted outcrossing (0–1.8%)43, combined with low recombination in pericentromeric regions, has resulted in modern germplasm that shows limited regional haplotype diversity44. We investigated the frequency and distribution of genome diversity by survey sequencing four diverse barley cultivars (‘Bowman’, ‘Barke’, ‘Igri’ and ‘Haruna Nijo’) and an H. spontaneum accession (Methods and Supplementary Note 8) to a depth of 5–25-fold coverage, and mapping sequence reads against the barley cultivar ‘Morex’ gene space. We identified more than 15 million non-redundant single-nucleotide variants (SNVs). H. spontaneum contributed almost twofold more SNV than each of the cultivars (Supplementary Table 28). Up to 6 million SNV per accession could be assigned to chromosome arms, including up to 350,000 associated with exons (Supplementary Table 29). Approximately 50% of the exon-located SNV were integrated into the genetic/physical framework (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 30 and Supplementary Fig. 31), providing a platform to establish true genome-wide marker technology for high-resolution genetics and genome-assisted breeding.

Barley chromosomes indicated as inner circle of grey bars. Connector lines give the genetic/physical relationship in the barley genome. SNV frequency distribution displayed as five coloured circular histograms (scale, relative abundance of SNVs within accession; abundance, total number of SNVs in non-overlapping 50-kb intervals of concatenated ‘Morex’ genomic scaffold; range, zero to maximum number of SNVs per 50-kb interval). Selected patterns of SNV frequency indicated by coloured arrowheads (for further details see Supplementary Note 8). Colouring of arrowheads refers to cultivar with deviating SNV frequency for the respective region.

We observed a decrease in SNV frequency towards the centromeric and peri-centromeric regions of all barley chromosomes, a pattern that seemed more pronounced in the barley cultivars. This trend was supported by SNV identified in RNA-seq data from six additional cultivars mapped onto the Morex genomic assembly (Supplementary Note 8.2). We attribute this pattern of eroded genetic diversity to low recombination in the pericentromeric regions, which reduces effective population size and consequently haplotype diversity. Whereas H. spontaneum may serve here as a reservoir of genetic diversity, using this diversity may itself be compromised by restricted recombination and the consequent inability to disrupt tight linkages between desirable and deleterious alleles. Surprisingly, the short arm of chromosome 4H had a significantly lower SNV frequency than all other barley chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 33). This may be a consequence of a further reduction in recombination frequency on this chromosome, which is genetically (but not physically) shortest. Reduced SNV diversity was also observed in regions we interpret to be either the consequences of recent breeding history or could indicate landmarks of domestication (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The size of Triticeae cereal genomes, due to their highly repetitive DNA composition, has severely compromised the assembly of whole-genome shotgun sequences and formed a barrier to the generation of high-quality reference genomes. We circumvented these problems by integrating complementary and heterogeneous sequence-based genomic and genetic data sets. This involved coupling a deep physical map with high density genetic maps, superimposing deep short-read whole-genome shotgun assemblies, and annotating the resulting linear, albeit punctuated, genomic sequence with deep-coverage RNA-derived data (full-length cDNA and RNA-seq). This allowed us to systematically delineate approximately 4 Gb (80%) of the genome, including more than 90% of the expressed genes. The resulting genomic framework provides a detailed insight into the physical distribution of genes and repetitive DNA and how these features relate to genetic characteristics such as recombination frequency, gene expression and patterns of genetic variation.

The centromeric and peri-centromeric regions of barley chromosomes contain a large number of functional genes that are locked into recombinationally ‘inert’ genomic regions45,46. The gene-space distribution highlights that these regions expand to almost 50% of the physical length of individual chromosomes. Given well-established levels of conserved synteny, this will probably be a general feature of related grass genomes that will have important practical implications. For example, infrequent recombination could function to maintain evolutionarily selected and co-adapted gene complexes. It will certainly restrict the release of the genetic diversity required to decouple advantageous from deleterious alleles, a potential key to improving genetic gain. Understanding these effects will have important consequences for crop improvement. Moreover, for gene discovery, forward genetic strategies based on recombination will not be effective in these regions. Whereas alternative approaches exist for some targets (for example, by coupling resequencing technologies with collections of natural or induced mutant alleles), for most traits it remains a serious impediment. Some promise may lie in manipulating patterns of recombination by either genetic or environmental intervention47. Quite strikingly, our data also reveal that a complex layer of post-transcriptional regulation will need to be considered when attempting to link barley genes to functions. Connections between post-transcriptional regulation such as alternative splicing and functional biological consequences remain limited to a few specific examples48, but the scale of our observations suggest this list will expand considerably.

In conclusion, the barley gene space reported here provides an essential reference for genetic research and breeding. It represents a hub for trait isolation, understanding and exploiting natural genetic diversity and investigating the unique biology and evolution of one of the world’s first domesticated crops.

Methods Summary

Methods are available in the online version of the paper.

Online Methods

Building the physical map

BAC clones of six libraries of cultivar ‘Morex’9,49 were analysed by high information content fingerprinting (HICF)7,9. A total of 571,000 edited profiles was assembled using FPC v9.28 (Supplementary Table 2) (Sulston score threshold of 10−90, tolerance = 5, tolerated Q clones = 10%). Nine iterative automated re-assemblies were performed at successively reduced stringency (Sulston score of 10−85 to 10−45). A final step of manual merging of FPC contigs was performed at lower stringency (Sulston score threshold 10−25) considering genetic anchoring information for markers with a genetic distance ≤ ± 5 cM. This produced 9,265 FPcontigs (approximately 14-fold haploid genome coverage) (Supplementary Table 2).

Genomic sequencing

BAC-end sequencing (BES). BAC insert ends were sequenced using Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Note 2.1). Vector and quality trimming of sequence trace files was conducted using LUCY50 (http://www.jcvi.org/cms/research/software/). Short reads (that is, < 100 bp) were removed. Organellar DNA and barley pathogen sequences were filtered by BLASTN comparisons to public sequence databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

BAC shotgun sequencing (BACseq). Seed BACs of the FPC map were sequenced to reveal gene sequence information for physical map anchoring. 4,095 BAC clones were shotgun sequenced in pools of 2 × 48 individually barcoded BACs on Roche/454 GS FLX or FLX Titanium51,52. Sequences were assembled using MIRA v3.2.0 (http://www.chevreux.org/projects_mira.html) at default parameters with features ‘accurate’, ‘454’, ‘genome’, ‘denovo’. An additional 2,183 gene-bearing BACs (Supplementary Note 3.2) were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000 in 91 combinatorial pools13. Deconvoluted reads were assembled using VELVET53. Assembly statistics are given in Supplementary Table 4.

Whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Illumina paired-end (PE; fragment size ∼350 bp) and mate-pair (MP; fragment size ∼2.5 kb) libraries were generated from fragmented genomic DNA54 of different barley cultivars (‘Morex’, ‘Barke’, ‘Bowman’, ‘Igri’) and an S3 single-seed selection of a wild barley accession B1K-04-1255 (Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum). Libraries were sequenced by Illumina GAIIx and Hiseq 2000. Genomic DNA of cultivar ‘Haruna Nijo’ (size range of 600–1,000 bp) was sequenced using Roche 454 GSFLX Titanium chemistry.

Whole-genome shotgun sequence assembly

PE and MP whole-genome shotgun libraries were calibrated for fragment sizes by mapping pairs against the chloroplast sequence of barley (NC_008590) using BWA56. Sequences were quality trimmed and de novo assembled using CLC Assembly Cell v3.2.2 (http://www.clcbio.com/). Independent de novo assemblies were performed from data of cultivars ‘Morex’, ‘Bowman’ and ‘Barke’.

Transcriptome sequencing

Eight tissues of cultivar ‘Morex’ (three biological replications each) earmarking stages of the barley life cycle from germinating grain to maturing caryopsis were selected for deep RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Plant growth, sampling and sequencing is detailed in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Note 6). Further mRNA sequencing data was generated from eight additional spring barley cultivars within a separate study and was used here for sequence diversity analysis (Supplementary Note 8.2).

Genetic framework of the physical map

The genetic framework for anchoring the physical map of barley was built on a single-nucleotide variation (SNV) map57 (Supplementary Note 4.3) which provided the highest marker density (3,973) and resolution (N = 360, RIL/F8) for a single bi-parental mapping population in barley. Additional high-density genetic marker maps (Supplementary Note 4.3) were compared and aligned on the basis of shared markers. Furthermore, we used genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS)58 to generate high-density genetic maps comprising 34,396 SNVs and 21,384 SNVs as well as 241,159 and 184,796 dominant (presence/absence) tags for the two doubled haploid populations Oregon Wolfe Barley14 and Morex × Barke45, respectively. Altogether 498,165 marker sequence tags were used (Supplementary Table 11).

Genetic anchoring

Genetic integration of the physical map involved procedures of direct and indirect anchoring.

Direct anchoring. Genetic markers were assigned to BAC clones/BAC contigs by three different procedures (Supplementary Note 4.3 and Supplementary Table 9). 2,032 PCR-based markers from published genetic maps59,60 were PCR-screened on custom multidimensional (MD) DNA pools (http://ampliconexpress.com/) obtained from BAC library HVVMRXALLeA9. A single haploid genome equivalent of these MD pools was used for multiplexed screening of 42,302 barley EST-derived unigenes represented on a custom 44K Agilent microarray as previously described61. 27,231 barley unigenes, comprising 1,121 with a genetic map position45,62, could be assigned to 12,313 BACs. 14,600 clones from BAC library HVVMRXALLhA were screened with 3,072 SNP markers on Illumina GoldenGate assays45 leading to 1,967 markers directly assigned to BACs13; approximately one third of this information has been included in the present work.

Indirect anchoring. Sequence resources associated with the FPCmap framework provided the basis for extensive in silico integration of genetic marker information (Supplementary Note 4.3 and Supplementary Table 11). Repeat masked BES sequences, sequences of anchored markers and 6,295 sequenced BACs allowed integration of 307 Mb of ‘Morex’ whole-genome shotgun contigs into the FPC map. Genetic markers and barley gene sequences were positioned to this reference by strict sequence homology association. Overall 8,170 (∼4.6 Gb) BAC contigs received sequence and/or anchoring information (Supplementary Note 4). 4,556 FPC contigs (Σ = 3.9 Gb) were anchored to the genetic framework.

Analysis of repetitive DNA and repeat masking

Repeat detection and analysis was undertaken as previously described18,20 with the exception of an updated repeat library complemented by de novo detected repetitive elements from barley (Supplementary Note 5).

Gene annotation, functional categorization and differential expression

Publically available barley full-length cDNAs24 and RNA-seq data generated in the project (Supplementary Note 6) were used for structural gene calling (Supplementary Note 7). Full-length cDNAs and RNA-seq data were anchored to repeat masked whole-genome shotgun sequence contigs using GenomeThreader63 and CuffLinks64, respectively, the latter providing also information of alternatively spliced transcripts. Structural gene calls were combined and the longest ORF for each locus was used as representative for gene family analysis (Supplementary Note 7.1.2).

Gene family clustering was undertaken using OrthoMCL (Supplementary Note 7.1.3) by comparing against the genomes of Oryza sativa (RAP2), Sorghum bicolor, Brachypodium distachyon (v 1.4) and Arabidopsis thaliana (TAIR10 release).

Analysis of differential gene expression (Supplementary Note 7.2) was performed on RNA-seq data using CuffDiff65.

Analysis of sequence diversity

Genome-wide SNV was assessed by mapping (BWA v0.5.9-r1656) the original sequence reads of sequenced genotypes to a de novo assembly of cultivar ‘Morex’. Sequence reads from RNA-seq were mapped against the ‘Morex’ assembly. Details are provided in Supplementary Note 8.

Accession codes

Data deposits

Sequence resources generated or compiled in this study have been deposited at EMBL/ENA or NCBI GenBank. A full list of sequence raw data accession numbers as well as URLs for data download, visualization or search are provided in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table 1.

References

Purugganan, M. D. & Fuller, D. Q. The nature of selection during plant domestication. Nature 457, 843–848 (2009)

Blake, T., Blake, V., Bowman, J. & Abdel-Haleem, H. in Barley: Production, Improvement and Uses (ed. S. E. Ullrich ) 522–531 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011)

Nevo, E. et al. Evolution of wild cereals during 28 years of global warming in Israel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3412–3415 (2012)

Grando, S. & Macpherson, H. G. in Proceedings of the International Workshop on Food Barley Improvement, 14–17 January 2002, Hammamet, Tunisia 156 (ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria, 2005)

Collins, H. M. et al. Variability in fine structures of noncellulosic cell wall polysaccharides from cereal grains: potential importance in human health and nutrition. Cereal Chem. 87, 272–282 (2010)

Bockelman, H. E. & Valkoun, J. in Barley: Production, Improvement, and Uses (ed. S. E. Ullrich ) 144–159 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011)

Luo, M.-C. et al. High-throughput fingerprinting of bacterial artificial chromosomes using the snapshot labeling kit and sizing of restriction fragments by capillary electrophoresis. Genomics 82, 378–389 (2003)

Soderlund, C., Humphray, S., Dunham, A. & French, L. Contigs built with fingerprints, markers, and FPC V4.7. Genome Res. 10, 1772–1787 (2000)

Schulte, D. et al. BAC library resources for map-based cloning and physical map construction in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Genomics 12, 247 (2011)

Doležel, J. et al. Plant genome size estimation by flow cytometry: inter-laboratory comparison. Ann. Bot. 82, 17–26 (1998)

Paux, E. et al. A physical map of the 1-gigabase bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science 322, 101–104 (2008)

Madishetty, K., Condamine, P., Svensson, J. T., Rodriguez, E. & Close, T. J. An improved method to identify BAC clones using pooled overgos. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, e5 (2007)

Lonardi, S. et al. Barcoding-free BAC pooling enables combinatorial selective sequencing of the barley gene space. preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1112.4438 (2011)

Poland, J. A., Brown, P. J., Sorrells, M. E. & Jannink, J.-L. Development of high-density genetic maps for barley and wheat using a novel two-enzyme genotyping-by-sequencing approach. PLoS ONE 7, e32253 (2012)

Mayer, K. F. X. et al. Unlocking the barley genome by chromosomal and comparative genomics. Plant Cell 23, 1249–1263 (2011)

Schnable, P. S. et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science 326, 1112–1115 (2009)

Wicker, T. et al. A whole-genome snapshot of 454 sequences exposes the composition of the barley genome and provides evidence for parallel evolution of genome size in wheat and barley. Plant J. 59, 712–722 (2009)

The International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature 463, 763–768 (2010)

International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436, 793–800 (2005)

Paterson, A. H. et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 457, 551–556 (2009)

Kronmiller, B. A. & Wise, R. P. TEnest: automated chronological annotation and visualization of nested plant transposable elements. Plant Physiol. 146, 45–59 (2008)

Ohshima, K. & Okada, N. SINEs and LINEs: symbionts of eukaryotic genomes with a common tail. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 475–490 (2005)

Wessler, S. R., Bureau, T. & White, S. LTR-retrotransposons and MITEs: important players in the evolution of plant genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 5, 814–821 (1995)

Matsumoto, T. et al. Comprehensive sequence analysis of 24,783 barley full-length cDNAs derived from 12 clone libraries. Plant Physiol. 156, 20–28 (2011)

Zhang, P. et al. MetaCyc and AraCyc. Metabolic pathway databases for plant research. Plant Physiol. 138, 27–37 (2005)

Wicker, T. et al. Frequent gene movement and pseudogene evolution is common to the large and complex genomes of wheat, barley, and their relatives. Plant Cell 23, 1706–1718 (2011)

van der Biezen, E. A. & Jones, J. D. G. The NB-ARC domain: a novel signalling motif shared by plant resistance gene products and regulators of cell death in animals. Curr. Biol. 8, R226–R228 (1998)

Wei, F., Wing, R. A. & Wise, R. P. Genome dynamics and evolution of the Mla (powdery mildew) resistance locus in barley. Plant Cell 14, 1903–1917 (2002)

Halterman, D. A. & Wise, R. P. A single-amino acid substitution in the sixth leucine-rich repeat of barley MLA6 and MLA13 alleviates dependence on RAR1 for disease resistance signaling. Plant J. 38, 215–226 (2004)

Seeholzer, S. et al. Diversity at the Mla powdery mildew resistance locus from cultivated barley reveals sites of positive selection. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 497–509 (2010)

Jacobs, A. K. et al. An Arabidopsis callose synthase, GSL5, is required for wound and papillary callose formation. Plant Cell 15, 2503–2513 (2003)

Jiao, Y. et al. A transcriptome atlas of rice cell types uncovers cellular, functional and developmental hierarchies. Nature Genet. 41, 258–263 (2009)

Conti, E. & Izaurralde, E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: molecular insights and mechanistic variations across species. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 316–325 (2005)

Kalyna, M. et al. Alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay modulate expression of important regulatory genes in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 2454–2469 (2012)

Lewis, B. P., Green, R. E. & Brenner, S. E. Evidence for the widespread coupling of alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 189–192 (2003)

Bhuvanagiri, M., Schlitter, A. M., Hentze, M. W. & Kulozik, A. E. NMD: RNA biology meets human genetic medicine. Biochem. J. 430, 365–377 (2010)

Rayson, S. et al. A role for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in plants: pathogen responses are induced in Arabidopsis thaliana NMD mutants. PLoS ONE 7, e31917 (2012)

Riehs-Kearnan, N., Gloggnitzer, J., Dekrout, B., Jonak, C. & Riha, K. Aberrant growth and lethality of Arabidopsis deficient in nonsense-mediated RNA decay factors is caused by autoimmune-like response. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 5615–5624 (2012)

Jeong, H.-J. et al. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay factors, UPF1 and UPF3, contribute to plant defense. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 2147–2156 (2011)

Lu, T. et al. Function annotation of the rice transcriptome at single-nucleotide resolution by RNA-seq. Genome Res. 20, 1238–1249 (2010)

Guttman, M. & Rinn, J. L. Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature 482, 339–346 (2012)

Chinen, M. & Tani, T. Diverse functions of nuclear non-coding RNAs in eukaryotic gene expression. Front. Biosci. 17, 1402–1417 (2012)

Abdel-Ghani, A. H., Parzies, H. K., Omary, A. & Geiger, H. H. Estimating the outcrossing rate of barley landraces and wild barley populations collected from ecologically different regions of Jordan. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 588–595 (2004)

Comadran, J. et al. Patterns of polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium in cultivated barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122, 523–531 (2011)

Close, T. J. et al. Development and implementation of high-throughput SNP genotyping in barley. BMC Genomics 10, 582 (2009)

Thiel, T. et al. Evidence and evolutionary analysis of ancient whole-genome duplication in barley predating the divergence from rice. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 209 (2009)

Martinez-Perez, E. & Moore, G. To check or not to check? The application of meiotic studies to plant breeding. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 222–227 (2008)

Halterman, D. A., Wei, F. S. & Wise, R. P. Powdery mildew-induced Mla mRNAs are alternatively spliced and contain multiple upstream open reading frames. Plant Physiol. 131, 558–567 (2003)

Yu, Y. et al. A bacterial artificial chromosome library for barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and the identification of clones containing putative resistance genes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101, 1093–1099 (2000)

Chou, H.-H. & Holmes, M. H. DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal. Bioinformatics 17, 1093–1104 (2001)

Steuernagel, B. et al. De novo 454 sequencing of barcoded BAC pools for comprehensive gene survey and genome analysis in the complex genome of barley. BMC Genomics 10, 547 (2009)

Taudien, S. et al. Sequencing of BAC pools by different next generation sequencing platforms and strategies. BMC Res. Notes 4, 411 (2011)

Zerbino, D. R. & Birney, E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829 (2008)

Stein, N., Herren, G. & Keller, B. A new DNA extraction method for high-throughput marker analysis in a large-genome species such as Triticum aestivum. Plant Breed. 120, 354–356 (2001)

Hübner, S. et al. Strong correlation of the population structure of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) across Israel with temperature and precipitation variation. Mol. Ecol. 18, 1523–1536 (2009)

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009)

Comadran, J. et al. A homologue of Antirrhinum CENTRORADIALIS is a component of the quantitative photoperiod and vernalization independent EARLINESS PER SE 2 locus in cultivated barley. Nature Genet. (in the press).

Elshire, R. J. et al. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE 6, e19379 (2011)

Sato, K., Nankaku, N. & Takeda, K. A high-density transcript linkage map of barley derived from a single population. Heredity 103, 110–117 (2009)

Stein, N. et al. A 1000 loci transcript map of the barley genome – new anchoring points for integrative grass genomics. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 823–839 (2007)

Liu, H. et al. Highly parallel gene-to-BAC addressing using microarrays. Biotechniques 50, 165–174 (2011)

Potokina, E. et al. Gene expression quantitative trait locus analysis of 16,000 barley genes reveals a complex pattern of genome-wide transcriptional regulation. Plant J. 53, 90–101 (2008)

Gremme, G., Brendel, V., Sparks, M. E. & Kurtz, S. Engineering a software tool for gene structure prediction in higher organisms. Inf. Softw. Technol. 47, 965–978 (2005)

Trapnell, C. et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols 7, 562–578 (2012)

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010)

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported from the following funding sources: German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) grant 0314000 “BARLEX” to K.F.X.M., M.P., U.S. and N.S.; Leibniz Association grant (Pakt f. Forschung und Innovation) to N.S.; European project of the 7th framework programme “TriticeaeGenome” to R.W., A.S., K.F.X.M., M.M. and N.S.; SFB F3705, of the Austrian Wissenschaftsfond (FWF) to K.F.X.M.; ERA-NET PG project “BARCODE” grant to M.M., N.S. and R.W.; Scottish Government/BBSRC grant BB/100663X/1 to R.W., D.M., P.H., J.R., M.C. and P.K.; National Science Foundation grant DBI 0321756 “Coupling EST and Bacterial Artificial Chromosome Resources to Access the Barley Genome” and DBI-1062301 "Barcoding-Free Multiplexing: Leveraging Combinatorial Pooling for High-Throughput Sequencing" to T.J.C. and S.L.; USDA-CSREES-NRI grant 2006-55606-16722 “Barley Coordinated Agricultural Project: Leveraging Genomics, Genetics, and Breeding for Gene Discovery and Barley Improvement” to G.J.M., R.P.W., T.J.C. and S.L.; the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Plant Genome, Genetics and Breeding Program of USDA-CSREES-NIFA grant 2009-65300-05645 “Advancing the Barley Genome” to T.J.C., S.L. and G.J.M.; BRAIN and NBRP-Japan grants to K.S., Japanese MAFF Grant (TRG1008) to T.M. A full list of acknowledgements is in the Supplementary Information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

See list of consortium authors. R.A., D.S., H.L., B.S., S.T., M.G., F.C., T.N., M.S., M.P., H.G., P.H., T.S., K.F.X.M., R.W. and N.S. contributed equally to their respective work packages and tasks.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text, Supplementary Figures 1-33, Supplementary Tables 1-24 and 26-33 (see separate file for Supplementary Table 25) and Supplementary References – see Contents for more details. (PDF 6676 kb)

Supplementary Data

This file contains Supplementary Table 25, which shows GO terms and PFAM domains over- and underrepresented in barley-expanded gene clusters. (XLS 117 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/).

About this article

Cite this article

The International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 491, 711–716 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11543

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11543

This article is cited by

-

High-resolution mapping of Ryd4Hb, a major resistance gene to Barley yellow dwarf virus from Hordeum bulbosum

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2024)

-

Dehydrin genes allelic variations in some genotypes of local wild and cultivated barley (Hordeum L.) in Syria

Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (2024)

-

Identification and map-based cloning of long glume mutant gene lgm1 in barley

Molecular Breeding (2024)

-

BarleyExpDB: an integrative gene expression database for barley

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers for genetic diversity and population structure study in Ethiopian barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germplasm

BMC Genomic Data (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.