Tiny ants construct an elaborate ambush to immobilize and kill much larger insects.

Abstract

To meet their need for nitrogen in the restricted foraging environment provided by their host plants, some arboreal ants deploy group ambush tactics in order to capture flying and jumping prey that might otherwise escape1,2,3,4. Here we show that the ant Allomerus decemarticulatus uses hair from the host plant's stem, which it cuts and binds together with a purpose-grown fungal mycelium, to build a spongy ‘galleried’ platform for trapping much larger insects. Ants beneath the platform reach through the holes and immobilize the prey, which is then stretched, transported and carved up by a swarm of nestmates. To our knowledge, the collective creation of a trap as a predatory strategy has not been described before in ants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

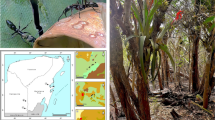

Allomerus decemarticulatus (Myrmicinae) is specifically associated with the Amazonian ant-plant Hirtella physophora (Chrysobalanaceae), which houses colonies in leaf pouches. Workers build galleried structures on their host plant's stems in which they pierce numerous holes that are slightly larger in diameter than their heads, allowing them to enter and exit5 (Fig. 1a). First, they cut plant hairs (trichomes) along the stems, clearing a path. Then, using uncut trichomes as pillars, they build the gallery's vault by binding cut trichomes together with a compound that they regurgitate (for details, see supplementary information). Later, this structure is reinforced by the mycelium of a complex of sooty-mould species that has been manipulated by the ants. Fungal growth starts around the holes and then spreads rapidly to the rest of the structure.

a, Base of the lamina of two Hirtella physophora leaves: the pouches serve as ant nests, which are interconnected by a gallery pierced with numerous holes. b, Start of the capture of a locust. c, One hour later, recruited workers have left the gallery in order to bite, sting and stretch the prey. d, Completion of a cricket capture.

We noted that the stems of 34 young seedlings, which had not yet developed leaf pouches, did not bear fungus; nine saplings raised in a greenhouse in the absence of Allomerus developed leaf pouches but never bore fungus. However, 15 saplings raised in the presence of ants bore mycelia, whose development was limited to the galleries. When we eliminated the associated ants from five of the 15, the fungus on the galleries grew into a disorganized structure, and none of the nine new stems that developed bore any fungus at all.

Because prey seemed to be immobilized on the top surface of these galleries, we investigated whether these structures could be acting as a trap. Our observations revealed that Allomerus workers hide in the galleries with their heads just under the holes, mandibles wide open, seemingly waiting for an insect to land. To kill the insect, they grasp its free legs, antennae or wings, and move in and out of holes in opposite directions until the prey is progressively stretched against the gallery and swarms of workers can sting it (Fig. 1b–d). The ants then slide the prey over the top of the gallery — again moving in and out of holes, but this time in the same direction. They move it slowly towards a leaf pouch, where they carve it up.

Because the requirement for protein is crucial, some arboreal ants consume parts of the Hemiptera that they attend6, others rely on microsymbionts to recycle nitrogen7, and some have a thin cuticle and non-proteinaceous venom that economizes on nitrogen use8. Nevertheless, most of them must capture prey that land on their host plant3. Given this constraint, the tiny A. decemarticulatus workers have developed a tripartite association with their host plant and a fungus collectively to ambush their prey.

References

Heil, M. & McKey, D. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 425–553 (2003).

Hölldobler, B. & Wilson, E. O. The Ants (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1990).

Dejean, A. & Corbara, B. in Arthropods of Tropical Forests. Spatio-temporal Dynamics and Resource Use in the Canopy (eds Basset, Y., Novotny, V., Miller, S. E. & Kitching, R. L.) 341–347 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 2003).

Morais, H. C. Insectes Soc. 41, 339–342 (1994).

Benson, W. W. in Amazonia (eds Prance, G. & Lovejoy, T. E.) 239–266 (Pergamon, New York, 1985).

Offenberg, J. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 49, 304–310 (2001).

van Borm, S., Buschinger, A., Boomsma, J. J. & Billen, J. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 2023–2027 (2002).

Davidson, D. W. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 61, 153–181 (1997).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dejean, A., Solano, P., Ayroles, J. et al. Arboreal ants build traps to capture prey. Nature 434, 973 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/434973a

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/434973a

This article is cited by

-

The origin of human pathogenicity and biological interactions in Chaetothyriales

Fungal Diversity (2023)

-

The symbiosis between Philidris ants and the ant-plant Dischidia major includes fungal and algal associates

Symbiosis (2021)

-

Consistent patterns of fungal communities within ant-plants across a large geographic range strongly suggest a multipartite mutualism

Mycological Progress (2021)

-

Convergent structure and function of mycelial galleries in two unrelated Neotropical plant-ants

Insectes Sociaux (2017)

-

The reproductive biology of the myrmecophyte, Hirtella physophora, and the limitation of negative interactions between pollinators and ants

Arthropod-Plant Interactions (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.